Ukrainian Camouflage Net-Making Workshop: Between Art, War, and Hope

Valeria Radkevych

“What we are making here is contemporary art,” the woman burst out in laughter behind me. I, a contemporary art critic, am staring at what looks like an industrial site, with a clear intention of writing about this place. I agree with this rather bold statement made by one of the volunteers, because, after all, we are inside the walls of the Lviv National Academy of Art. And the industrial atmosphere is created by the presence of a military camouflage net-making workshop. I graduated from the Academy in 2017, and haven’t set foot in the building ever since. However, my grandmother spends days on end here, weaving kilometers of camouflage nets. Her hands move with confidence and precision. A contemporary Arachne–I thought, amused–compelled to weave for eternity as an act of resilience, care and protection. Defying the destructive power of the gods of war, challenging death in the act of creation. What my grandmother is making might save the lives of men, disguise their positions along the frontline, and ultimately, buy them some time to protect our home, and theirs. Yet, the mood among the volunteers is humble: nobody here is summoning Athena for a weaving challenge. On the contrary, their hands run against time; time is a precious resource, the most important companion of military volunteers.

“Look, work around the corners of the base nets,” grandma says, “then twist it, and go over the other two sections, this way you can cover more space”. My clumsy little hands start to slowly curl and turn the ribbons around the base nets. In my mind, I am playing a cheap cell phone game, where the lines have to be perfectly traced, without crossing or overlapping each other. After a few minutes, grandma comes over, takes a critical look at my creation, and, without saying a word, pulls the whole thing undone, only to recompose it again, in a better way. “Remember, it has to hide, not expose,” she says, pointing at large holes between the ribbons I worked on.

I go to explore the rest of the workshop, which fills a large space inside the Academy’s textile department that has been dedicated to netmaking. The corridor is filled with natural light from huge windows on one side, which illuminate a long net stretched on the wall on the other side. Under the window seals–boxes and boxes of things, uncut rolls of material, goofy masking “hats” for military headpieces, sacks ready to be undone thread by thread and become net bases, some sealed boxes to be shipped to the frontline locations. With permission to stick my nose everywhere around the place, I open every box like a curious monkey. One of them is full of handmade kittens: paper kittens, little stuffed kittens with googly eyes, and drawings of kittens. “We put a few kittens inside every shipment,” said Olesya Datsko, my former professor who runs the workshop, “we hold some classes with local kids, and they all want to make something to send to the soldiers in the frontline. The guys [soldiers] are so enthusiastic about the kittens!”. I picked a small blue, googly-eyed stuffed animal. “Take it”, says Professor Datsko, “it is full of love”.

Olesya Datsko greeted me with a big hug. She went on to present me to everyone at the workshop: “This is Valeria, she used to study with us, and she is the granddaughter of Olenka!”. It seemed that the connection to my grandma caused more enthusiasm than any other facet of my biography related by the professor. My grandmother is a local star. She is friendly, and sociable, she works hard and does it with incredible ease. She has been there since the very beginning. At the moment, she is working on a net strung on a strange cube-shaped wooden frame. The completed parts lay inside the cube, while the empty base hangs from the sides. Every side of the cube can be worked on by two people simultaneously. Behind the cube are piles of ribbons organized by colors: dark brown, light ochre, olive, dark green, sand, and so on. The net makers can determine the classification of colors by consulting a list on the opposite wall that includes samples with the names of each color. Next to them are yellow papers with information about the current order of netting: the number and size of the net, the color, and the location of shipment. It looks like everything has been elevated to an industrial standard by the singular organizational talent of volunteers.

A special corner is dedicated to a few Ukrainian flags signed by the grateful soldiers, the official letters of gratitude from military groups, some children’s drawings, a teapot, and a few mugs. The place is a shelter, like a friendly home, where one comes for consolation and advice. People in this workshop (most of them women) spend full days here, bring their children and pets, celebrate birthdays, and take much-needed tea and coffee breaks. Everyone here feels that they are doing something important and takes pride in it. Netmaking is a hard, invisible work, ironically aimed at disguising–making someone else invisible. The students from the textile department have their artwork exhibited in these corridors. It creates an eerie marriage between the art that comes from a place of creativity and the craft that comes from a place of military need. In fact, this is hardly the only net-making volunteer center, but the neat connection between camo weaving and visual art is evident here more than in other places. A lifesaving art of resistance, care, and heroic invisible labor, with a backdrop of painted textiles, photographs of fashion models, and hand-woven samples.

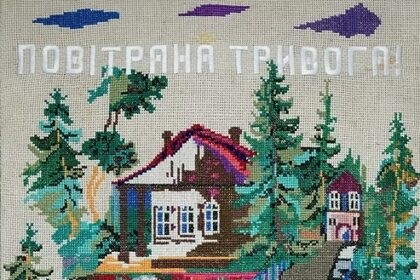

I have been to the Academy on a few different occasions during my most recent visit to Ukraine, intending to see the studios of the students, look at some specific artworks, and talk to a few artists. The usual curatorial routine that I love and cherish. As soon as I walked inside the main building, the security guard saw me back to the exit: “There is a bomb planted in the Academy, you cannot enter”. What do you mean by “bomb”? Startled, I remained standing outside the door that was shut behind me. Soon, another professor of mine arrived, a guilty look on her face: “Sorry about that. It happens almost every Friday. Someone calls and says the academy is mined. I am so sorry”. I suddenly felt entertained. Is it some kind of performance? In the meantime, a few police cars and a military van pulled up to the entrance. A few men with bored faces went straight inside. “War is everywhere”, the professor shrugged. She then left me standing alone in the Academy’s front yard, filled with students who were promptly exiled from their workshops. I had to call my grandmother, who was weaving her nets inside the building, and ask her to get out of there, just in case. “It really happens all the time”, she said, “we never leave. It is nothing, truly. Don’t worry”. And it was, in fact, nothing. A false alarm.

In February 2022, when the full-scale war became an undeniable reality, residents of cities like Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Sumy fled westward in search of safety. Although no part of Ukraine has truly been safe since the invasion, during those first chaotic weeks, the Russian military focused its efforts on the eastern regions. This made the West a temporary refuge. According to the UN database, the number of those who hastily moved away from their homes as the Russian invasion entered its active phase is close to eight million people. Some of them left the country for countries like Poland, Germany, Italy, Belgium or Great Britain. Others migrated to the cities at the Western borders of Ukraine and stayed there. Cities like Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Uzhhorod saw a sudden influx of displaced people and transformed almost overnight into dynamic volunteer hubs. Fueled by adrenaline and urgency, people collected clothes and food, opened their homes to strangers, and organized late-night rides to meet new arrivals at the train station after curfew.

Those who fled found shelter in unlikely places: galleries, schools, museums. In the early days of displacement, many were gripped with the need to stay active, to preserve their mental equilibrium through purpose. It was in this spirit that the netmaking workshop at the Lviv National Academy of Arts emerged, not only as a practical contribution to the war effort, but as a vital space of connection, care, and communal strength. “When all of it started, when Russian tanks entered Sumy, Kyiv, everybody rushed over here. And everyone wanted to be useful, to do something,” recalls Professor Olesya Datsko. “Here in the Academy, we had a little alumni reunion, because many important artists with careers came back to their Alma Mater to make camo nets.” It was Datsko who initiated the workshop within the Academy’s walls. What began as an improvised response soon evolved into a deeply collaborative practice: a blend of artistic instinct, survival urgency, and collective resilience.

In the early days of the full-scale Russian invasion the scarcity of materials sparked inventive solutions. Fishing nets were repurposed. A volleyball net arrived all the way from Spain, liberated by Datsko’s cousin, and shipped to Lviv. The next challenge was the filler, ribbons of fabric; not only difficult to find but also requiring careful attention to color. Camouflage is an adaptive art: colors must reflect the constantly shifting environment, dirt, grass, snow, and ash, depending on the terrain, weather, and ongoing destruction. The work was meticulous and continuous. Meanwhile, beyond logistics, the workshop became something more. As volunteers gathered to cut, dye, and weave, a new form of solidarity took root. They shared stories, grief, silence, and determination. The act of weaving itself became therapeutic, hands moving together in a rhythm that soothed minds and built bonds. As Datsko notes, “I started to think that the netmaking was an activity that profited more those who did it, rather than the military.” Now, the workshop hums with quiet urgency. Rolls of spunbond, a lightweight, water-repellent, and nonwoven fabric, lie ready to be transformed. Volunteers cut them into strips and sort them by color: olive, dirt, ochre. Each net is made to a specific military request, using exact ratios like 40% olive and 60% dirt, for instance. The patterns are calculated with care, and slowly, net by net, something essential takes shape: not only a tool for camouflage, but a tangible symbol of civilian resistance, collective care, and the quiet power of togetherness in wartime.

Total war is a term that refers to the traces of battle contained in virtually everything. Every thought, every action, every routine daily activity, acquisition, and conversation is soaked in the essence of war. It boils down to as little as a night out with a friend: “We have to be done by ten, otherwise we will not be back by the curfew,” or “Should I buy this dress or donate the money to the military group where my friends are serving?”. Those who fled the shellings, witnessed or experienced physical violence, and lost their homes and loved ones in the first weeks after the invasion, not only looked for a roof over their head–the weather between February and March in Ukraine is unpleasant–they also looked for support, human connection and healing. As a result, there was a pressing need for an articulated psychological support program. The UNDP (United Nations Development Program) in Ukraine initiated a multitude of formats, from group therapy sessions to individual and online sessions, when personal contact was impossible due to shellings. However, a talk with a psychologist can only take one so far. Lviv National Academy of Art offered a valuable supplement to this endeavor: the focus on creativity as a part of the art therapy process. “Center for Social Innovations” is an NGO founded by Uliana Shchurko, a professor at the Department of Art Management of the Academy. In 2022, it introduced the project “Lviv unites and fortifies: primary psychological help to the internally displaced individuals[1]”. The camo netmaking workshop became the heart of this initiative because it offered both manual work and human connection. In addition, it is believed that the Academy’s general environment can be therapeutic: the workshops and common spaces of the school are filled with the artwork of its students, providing a soothing, comforting feeling for those who inhabit these spaces. And so it was: people coming to the netmaking workshop to make square kilometers of lifesaving disguise, also came to enjoy genuine, close human contact, drawn together by the sense of urgency and a common goal, and overseen by numerous artworks of every technique and medium.

Olesya Datsko told me a story of a man who used to be a part of the netmaking community. We will call him M. M seemed to come out of nowhere, no documents on him, no cell phone, and one change of clothes. It turned out that he used to be an inmate in a prison in Sumy. When the active phase of war unfolded, the prisons released a lot of people under amnesty (within reason, of course). In their haste to leave, men did not manage to get their documents or personal possessions and took off in random directions. This is how M ended up in the Academy’s workshop. M seemed menacing and anti-social, almost frightening. This is when he reached out to the Professors, telling his story, unraveling facts about his handicap, which prevented him from serving in the military, and expressing the will to help and to get back to “normal life”. After a while, he befriended people in the workshop, the women found him some new clothes and, later, a cellphone, then the academy helped him get his passport back. After a few months, M got a job and rented an apartment. He rarely shows up at the workshop, being busy with his new life. There were no questions asked, no judgments passed, M was free to gradually prove his readiness to be a part of civilian society again. It is not a singular story, but a rather common example of the power of the community when it comes to social integration. Culture, art, work, and affectionate human connection brought M the inmate back to a clean slate: a task that many state agencies fail to accomplish.

To be fair, netmaking is far from being the only form of integration within Ukrainian society today. Social workers and activists work continuously on programs that benefit veterans of the war and their families, displaced individuals, and civilian victims of the atrocities of war. They provide prosthetics to the soldiers who lost their limbs and help them rehabilitate, they secure schools and build shelters for children to study in. However, the net making inside the walls of the Lviv National Academy of Arts represents a powerful union of art and community that acts as a protective shield, both literally and figuratively.

Camouflage netmaking workshops in Ukraine and abroad gather people together, giving them an occasion to create something with their hands, putting them in a social situation, and providing them with a sense of purpose and usefulness that everyone craves at the moment. This process became a symbol of resilience, to the point of representing the very model of Ukrainian society at war. At the Venice Biennale 2024, the Ukrainian pavilion presented camouflage netmaking as its central theme. The space of the pavilion was encircled by an architectural and sculptural project by Oleksandr Burlaka, titled Work. The installation is composed of vintage woven fabrics from the 1950s and earlier. It served as a base for three other art projects: the film Civilians. Invasion by Daniil Revkovskyi and Andrii Rachynskyi, the installation Best Wishes by Katya Buchatska, and the video Comfort Work by Andrii Dostliev and Lia Dostlieva. The artworks inside Burlaka’s installation offered a glimpse of civilian action and struggle in Ukraine after the invasion. In other words, Net Making , as the theme of the Ukrainian pavilion, reflected the essence of camouflage net weaving: struggle, consolation, togetherness, and help.

On a different note, the Ukrainian artist Daria Koltsova has been awarded the Kaiserring Stipendium Award by the Monchehaus Museum of Modern Art in Goslar, Germany for her work Camouflage in 2023. This artwork is, once again, a camo net, woven by the artist using canvases she painted specifically for the occasion. The artwork fluctuates between its purpose of being contemplated as art and its use as military gear. In Spring 2025 Koltsova went back to weaving the camouflage nets–this time for a public space event that was introduced inside the Ukrainian Contemporary Art Festival UKUFest in Tallinn. The camo material combined the artist’s own painted canvases cut into stripes, as well as paintings that were donated by Estonian Artists. The net was made by the artist herself, along with some volunteers who were recruited through social media sources. Ultimately, the net covered a public monument to the Estonian writer A.H. Tammsaare on one of Tallinn’s squares. Unlike the Venice Biennial work, which engaged the viewer inside an exhibition space, this net was doing exactly what it was meant to do: to disguise. By hiding a public monument, Daria Koltsova made a statement about the vulnerability of culture and its tangible equivalent to the exposed and vulnerable condition of Ukrainian civilians, stuck in a tragic gap between survival and the urge to take action.

Volunteer work in Ukraine is what maintains the resistance. The netmaking workshops are far from being just a feel-good story about the power of art and human connection. They are a poignant reminder of everything that Ukrainian society could collectively accomplish if it did not have to constantly protect itself from atrocious Russian attacks. It is a reminder of how Ukrainian civilians work for the safety of their country, by donating money for the needs of their friends and family members on the frontlines, spending hundreds of days weaving nets, all while begging the world not to look away. And the Lviv National Academy of Arts is just one piece in this mosaic of endless resistance, extreme fatigue, and faint hope. The net-making practice is generally perceived in Ukraine as voluntary work, performed by those who have the time and resources to do it. The camouflage net is an essential asset for military groups, which is always in demand. Therefore, the workshops continue to produce, and new ones are being opened, pulling the communities closer together. The desire to be useful and contribute to the common cause transcends any prejudice or judgement in Ukrainian society. In front of a common enemy and the imminent danger of extinction, net making seems like the least one can do. Projects like the 2024 Venice Biennale Ukrainian Pavilion and Daria Koltsova artwork reflect the meaning behind the practice, projecting it onto the international art scene, and becoming a loudspeaker for the Ukrainian struggle and Ukrainian resilience.

Valeria Radkevych is a Ukrainian freelance researcher, writer, and art critic. She holds an MA in Visual Arts from the University of Bologna and Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her work explores the intersections of contemporary art and politics, decolonial practices, and media, with a particular focus on the Ukrainian art scene. Based in Italy, she contributes to Artribune, Il Giornale dell’Arte, and Juliet Magazine. In 2024, she founded A Quiet Catalyst, a platform dedicated to art, social politics, and war (https://www.aquietcatalyst.com/).

Notes

- Internally displaced people, referred to as IDPs, have been forced to flee their homes by conflict, violence, persecution or disasters, however, they remain within the borders of their own country. Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (n.d.). Internally displaced people. UNHCR. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-protect/internally-displaced-people?utm_source=chatgpt.com ↑