The Great Indian Hyperfascism:

Art of Subjection and Survival Among One-Fifth of the World’s Population

Sandip K. Luis

Indian art since the anti-colonial era has developed without an avant-garde, and continues to remain so to this day.[1] A sustained form of collective militancy, whether cultural or political, has generally been discouraged within the Indian art world’s liberal and center-left constituency, as if testifying to a certain Gandhian ethic of non-violence (which, as a conjunctural rather than civilizational disposition, may appear not so much relapsing as status quoist upon closer examination). It is in this general cultural and political vacuum, not unique to the art world alone, that one may locate the gradual rise of Hindu militancy, which first came to serious notice with the assassination of M. K. Gandhi in 1948. Evolving from a scattered shadow state to a coordinated deep state,[2] and finally into a full-blown state power with the prime ministership of Narendra Modi in 2014, the so-called Sangh Parivar (a nebulous family of Hindu fundamentalist and militant organizations) has now pushed India into a state of “undeclared Emergency.”[3] Since India is the world’s most populated territory and a fragile Babel with almost two dozen officially recognized languages (while the unofficial estimate ranges between 100 and 1000), let’s call the present disjuncture, for the lack of a better term, “hyperfascist”—a fascism more fascist than the historical fascism originated in the interwar Italy.[4]

Given the great diversity and geographic expanse of India, and the limited scope of this brief reportage, a discussion of how artists and cultural activists have been grappling with the historical disjuncture created by Modi’s prime ministership can be triangulated by examining the following three representative locations: (i) the National Capital Region of Delhi, currently controlled by Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its “parental” organization, the extreme-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS); (ii) the state of Kerala, the last outpost of leftist governance in the country; and (iii) Kashmir, given the way the region has been turned into a vicious laboratory for testing the nation’s federalism and military jingoism. Whereas the first two offer a quasi-Lacanian schematization of the symbolic and the imaginary of the Indian contemporary respectively, the last provides an impossible access to the real of the region’s “fascistic” present.[5]

Delhi: The National Capital, the Neoliberal Symbolic

Over the past decade, the National Capital Region (NCR) has witnessed an unprecedented number of protest movements and violent crackdowns, owing to the city’s symbolic and strategic importance in the discourse of the nation. Noteworthy among them were the student-led movements such as “Occupy UGC!”, which gheraoed the University Grants Commission headquarters in New Delhi,[6] and the Rohith Vemula Movement, the first major nationwide protest after the BJP came to power, following the “institutional murder” of a Dalit research scholar in South India. Around the time of the COVID-19 outbreak, the city also witnessed mass protests against the anti-Muslim and anti-poor Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), with the Muslim subaltern neighborhood of Shaheen Bagh as the epicentre, as well as the anti-corporate farmers’ movement under the slogan ‘Dilli Chalo!’ (‘On to Delhi!’). These events were remarkable not only for creating a community of the marginalized adept at political dialogue and deliberation—contrary to the postcolonial figure of the unrepresentable or speechless subaltern—but also for their creative interventions into the very fabric of civic infrastructure. Cultural theorist and art historian Santhosh S intriguingly maps this infrastructure as beginning with the site imaginary of Velivada (‘Dalit ghetto’), popularized by the Rohith Vemula movement.[7] Moreover, these events saw a large number of young visual artists and student activists participating and immersing themselves in the everyday life of the community by creating striking graffiti, propaganda materials, and makeshift monuments,[8] along with new channels of communication such as the bi-weekly newsletter Trolley Times, which documented the farmers’ movement—at times called “the biggest protest in world history.” [9]

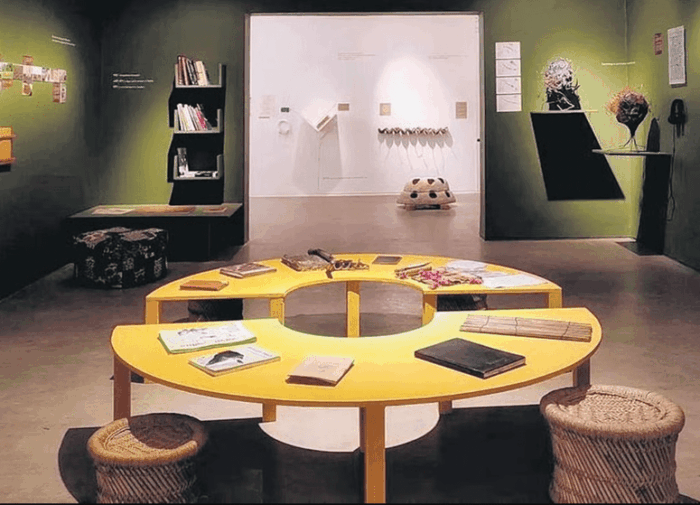

Given the mainstream art world’s entanglement with the interests of the state and capital even during fascistic times, the conventional artistic and curatorial response to the historic events outlined above can be described as either contemplative and detached at best, or opportunistic and parasitic at worst. Consider two exhibitions showcased at one of Delhi’s leading private art galleries, Vadehra Art Gallery (VAG): Many Acts of Reading: Critical Reflections on the Agrarian (2022) and Three Storey House (2025). Though the first, a group show initiated and curated by the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (VAG’s non-profit arm), was a rare and significant exercise in representing and responding to rural cultures, its expurgation of agrarian militancy—despite the original project, titled “AgriForum”, having been conceived during the farmers’ protest—turned its refurbished primitivism into an example of what Arundhati Roy calls the “NGO-ization of resistance.”[10] The second example, a solo show by senior artist-curator Anita Dube, came under rigorous public scrutiny for her alleged misappropriation of a widely disseminated anti-CAA protest poem written by the young Muslim poet-activist Aamir Aziz. The subtle erasure of the political symptomatically expressed in the first exhibition was now an explicit and brazen act as Dube’s textile wall-hangings rendered the poem’s iconic text hollowed out and thoroughly indecipherable, which was publicly called out by the poet himself.[11]

A polarizing development that made the growing proximity between India’s authoritarian politics and the ostensibly liberal and progressive art world explicit was the state-sponsored exhibition Jana Shakti: A Collective Power in 2023. Held at New Delhi’s National Gallery of Modern Art, the exhibition celebrated the 100 episodes of the Prime Minister’s monthly radio programme Mann Ki Baat (‘Matters of the Heart’) and featured well-known artists such as Atul Dodiya, Riyas Komu (co-founder of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale), and Thukral & Tagra (an artist duo briefly associated with Trolley Times). The artists, along with Kiran Nadar who was an advisor to the exhibition and founder of India’s major private art museum, the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), faced strong criticism from a broad section of cultural practitioners, academics, and activists for participating in what was widely seen as a propagandistic exercise by the right-wing government.[12] Notably, Bangladeshi photojournalist Shahidul Alam cancelled his solo-exhibition, which was scheduled to take place at KNMA, in protest against the museum’s compromised stance and internal censorship in violation of constitutional principles and labour laws.[13] An investigative report published by India’s reputed magazine The Caravan further revealed the climate of fear and self-censorship that pervades the creative field, where leading institutions of corporate patronage including KNMA, the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, and the newly established Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre in Mumbai, were all found to be complicit.[14]

With platforms for creative expression shrinking and the art infrastructure crumbling, a novel development emerged in the city, driven by the undying enthusiasm of a new generation of artists and art students. Similar to the Chinese phenomenon of “apartment art” that arose in response to increased censorship and the lack of accessible galleries,[15] private residential spaces were converted into temporary exhibition halls and film screening venues. Often referred to as “open studios” and scattered across the city and its margins, these spaces formed a parallel—if not confrontational—infrastructure for art, fostering micro-communities of artists. One such space, Studio Montage, run by the Progressive Artists’ League (PAL), stands out from other similar initiatives because of the collective’s principled rejection of mainstream art institutions and their neoliberal funding structures. Crowd-funded and known for holding exhibitions in working-class neighborhoods, as well as for its vocal anti-right-wing stance and recent active participation in the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel’s genocide of Palestinians, PAL recently faced a police crackdown and was forced to shift its residential space. [16]

Kerala: The Provincial Imaginary, the Left Populism

As the historically liberal and secular imaginary of the Indian art world has been shattered by the fascistic forces gathering momentum from the heartland of India, the southern state of Kerala with its leftist and multicultural legacy has risen to a position of cultural prominence. This is evidenced, for instance, by the national and international reception of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB), launched just two years before Modi’s ascension to power.[17] Kerala, long known for its human development indices comparable to those of developed countries in the West,[18] is also remarkable for its mostly accountable, inclusive, and dynamic public institutions, including state academies of art, literature, film, and theater. However, it is worth noting that the launch of KMB was a radical departure from this institutional tradition, which led to protests and the alienation of a significant number of Malayali artists and intellectuals.[19] During the KMB’s most recent edition in 2023, the organizers’ consistent evasion of due process and accountability culminated in international embarrassment,[20] as the event was postponed at the last moment following local laborers and contractors’ non-cooperation in protest.[21]

Despite the relative openness of the Keralite public sphere and the wishful imaginary it carries for the Indian art world with the formation of KMB, one must situate this development within the broader populist and authoritarian wave sweeping the subcontinent and steadily undermining liberal democratic institutions.[22] At a time when Kerala’s “left populism” dominates the mainstream with the electoral support of forward and other backward castes, it is often the outcaste communities, such as Dalits (formerly Untouchables) and Adivasis (tribal minorities), who provide a counterweight of critical conscience. Consider Vadayampady, a village just 25 kilometers from Kochi, which tested Kerala’s political conscience during 2017–18, when 180 Dalit families protested the construction of what they called a “caste wall.” This wall, still largely in place, blocked their access to public land after it was enclosed by a local Hindu temple committee led by members of the upper castes.

Despite the participation of young artists, and happening at the same time and in the same district as KMB’s most politically oriented yet populist edition—Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life, curated by Dube—the Vadayampady movement and the police brutality against its protesters found no place in the biennale’s discourse.[23] However, a collective sense of “Dalit pride” emanating from the protest created ripple effects within the exhibition and beyond. This was exemplified by Keralite artist Vipin Dhanurdharanan’s “Sahodarar” (“‘Brotherhood”/“Sisterhood”), an open community kitchen inspired by the anti-caste practice of mishrabhojanam (inter-dining) introduced by social reformer Sahodaran Ayyappan (1889–1968).[24] While Dhanurdharanan’s work falls within the genre of community-based and dialogical art practice, Berlin-based artist Sajan Mani has expanded similar concerns into a more confrontational performance. In his ongoing project Political Yoga and one of its iterations in Kerala, Mani humorously exposes Hindutva’s global branding of the meditative exercise of Yoga as both a tool of soft power and a justification of its casteist (Brahminical) ideology.

Kashmir, the “Real” Estate

A picture of the Indian contemporary, however schematic, can only be partially drawn through Delhi as the symbol of hyperfascist power in the north and Kerala as an alternative imaginary in the south, including the cracks within their structures revealed by radical artistic interventions from the margins. What both grounds and deconstructs India as a nation is its federalism which neither of these regions and their art scenes explicitly call into question. While Delhi holds an exceptional status as a Union Territory and NCR, and the Kerala government’s recent agitation to safeguard federalism against Modi’s authoritarian take over,[25] it is in relation to the “Kashmir question”—as old as the formation of the Republic of India itself—that India’s political present reveals its true dictatorial dimension.

The Kashmir Valley, with its Muslim-majority population of 7.8 million—larger than that of many European countries such as Denmark or Norway—has for decades endured extreme military suppression and forced disappearances following the unresolved territorial conflict between India and Pakistan further intensified by indigenous armed insurgency. This situation has deteriorated further with India’s recent revocation of the region’s constitutionally guaranteed federal autonomy, motivated largely by settler-colonial and real estate interests.[26] At a time when civil associations and political mobilizations routinely provoke violent backlash and communication blackouts by the Indian state, known models of artistic intervention—whether dialogically participatory or militantly avant-garde—have become largely unsustainable or inoperative. Historically deprived of the means of political and cultural representation, and thus confronted with the problem of the unrepresentable, many contemporary Kashmiri artists appear to embrace an aesthetic of the real which is often articulated through the visceral and the indexical, with an approach oscillating between performative madness and clinical detachment, absurdist humor rooted in the local folk tradition of Band Pather and melancholic lyricism as seen in the poems of Agha Shahid Ali (1949–2001). As a result, on the one hand, we find artists using their own bodies as a medium—with examples ranging from the performance artists Nasir Hassan and Khursheed Ali to Kashmiri Cabbage Walker (a mysterious public figure modeled after the eponymic character performed by Chinese artist Han Bing).[27]

On the other hand, paralleling such dark humor and corporeal aesthetic—also evident in the work of political cartoonists like Suhail Naqshbandi and Mir Suhail (now based in the United States)—we see an increasing number of photographers, many of whom are women. A particularly significant example is Her Pixel Story, a collective of Kashmiri women photographers founded in 2019. The group’s work is especially vital in an environment where platforms for gathering and sharing have been systematically dismantled by the security agencies, especially when they engage with the everyday lives of Kashmiris under occupation.[28]

Conclusion: Art neither Indian nor Contemporary

With the normalization of Hindu nationalism across much of India post-2014, it is through a certain transactional relationship between the art spaces of Delhi and Kerala that the Indian contemporary primarily defines itself, thanks to the concentration of philanthrocapitalism in the former and the formation of biennale and related events in the latter. However, if one takes the present historical disjuncture seriously—what I term “hyperfascist”—such an artworld can exist only briefly or superficially, for reasons ranging from the increasing proximity between the authoritarian state and the neoliberal elite to the opportunism of corporate patronage (as evidenced in the Jana Shakti exhibition as well as the recurring organizational crisis of KMB). In sharp contrast, it is in present-day Kashmir, where institutions of art and democracy are almost non-existent, that one might locate, if at all, the true character of the “Indian contemporary,” paradoxically disclosed in the very unbecoming of India as a nation, and of the contemporary as a shared spacetime. In the region’s broken social fabric under military occupation, even the apartment art and vanguardist campaigns of PAL in Delhi and the community interventions of Keralite artists appear to be luxuries, as testified in my conversation with young members of the Kashmiri art scene. (Confronted with severe censorship, most Kashmiri contemporary art is produced, disseminated, and discussed outside Kashmir—the most exemplary instance being the proposed Srinagar Biennale, one of whose iterations featured in the 4th KMB—yet such engagements lie beyond the purview of this report, which is concerned specifically with how cultural practitioners challenge political repression on the ground.)

As Salman B. Baba, co-founder of the Yusmarg Collective in Kashmir puts it, “In a space that is marked by surveillance, control and conflict, collectives offer a praxis that […] values connection over competition, presence over productivity […]. Collectives, thus, become trojan structures—not overt confrontations.”[29] The key term here is trojan—the spirit of collective uprising clandestinely nurtured in the everyday art of survival and fugitivity, waiting to be unleashed at the “right moment” (Kairos in Greek). As the distinction between Kashmir’s permanent state of exception and India’s current “undeclared Emergency”—not to mention similar conditions worldwide—is only blurring, and as individuals and institutions are increasingly stripped to bare lives and infrastructural skeletons, these survival tactics and strategies of resistance may soon become everyone’s lifeline.

Sandip K. Luis is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History & Art Appreciation at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. He received his Ph.D. and M.Phil. in Visual Studies from the School of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi (2019), and has previously taught at Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Delhi, and the University of Kerala. From 2019 to 2023, he held the position of Manager (Curatorial Research and Publication) at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. His areas of research and publication include theories of the avant-garde and Third World modernism, biennials, and the historiography of global contemporary art.

Notes

[1] Art critic and curator Geeta Kapur’s influential claim that Indian art lacked an avant-garde until the 1990s—the period of neoliberal globalization—is a historiographical error, especially when we consider the persistent difficulty of such a subjectivity to be historically present even after that decade. For further discussion, see my forthcoming publication, ”The Missing Avant-Garde: Art and Politics in India from 1947 to 1989.” For Kapur’s argument, see her When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India. New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2000, Chapter 10.

[2] Josy Joseph, The Silent Coup: A History of India’s Deep State. Chennai, India: Context, 2021.

[3] Arvind Narrain, India’s Undeclared Emergency: Constitutionalism and the Politics of Resistance. Chennai: Context, 2022. The Prime Minister and his parent organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) idea of ekta or akhandata (oneness or unity) is premised on violently excluding or repressing anything different from the ideology of Hindutva (“Hindu way of life”), which is as old as German Nazism. RSS, the world’s largest paramilitary volunteer organization, has infamously singled out Muslims, Christians, and Communists as the nation’s “internal enemies” in its foundational documents. Today, this hatred is more palpably visible in Hindutva’s treatment of the Muslims—the country’s largest minority roughly equal to the combined population of Germany, France, and Spain—and the leftists—often labelled ‘Urban Naxals’ and including lower-caste activists and intellectuals.

[4] I use the term “hyperfascism” for the following reason: Imagine the whole of Europe, the United States, Russia, and Australia—in other words, the entire “Western” world comprising around 1.25 billion people—falling under a single authoritarian ruler and his far-right party, and remaining so electorally for more than a decade. The title of “fascism” or even “neo-fascism”, however expansive and imposing its political aspiration might have been, would appear as a mere flyspeck before this gigantic juggernaut which has no parallels or precedents in world history. Now, consider the fact that even this apocalyptic imagery falls short of describing the everyday reality of contemporary India of 1.44 billion people. Hence the provisional term, “hyperfascism”—a fascism more actual than historical fascism instead of “postfascist,” an alternate term preferred by certain historians and commentators in the West.

[5] I use the term “fascistic” instead of “fascist” (not deviating from my earlier use of the word “hyperfascist”), inspired by Marxist intellectual Aijaz Ahmad’s differentiation between authoritarian formations of the present from the historical fascisms of the early 20th century. See Ahmad, Nothing Human is Alien to Me. New Delhi: Leftword Books, 2020, pp 132-33.

[6] “Watch ‘The Media Collective’ Explain the Occupy UGC Movement”, The Quint (6 Jan 2016) https://www.thequint.com/news/india/watch-the-media-collective-explain-the-occupy-ugc-movement#read-more Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[7] Santhosh S, ‘”Politics as Pedagogy”, e-flux: Architecture (10 March 2020) https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/education/322666/politics-as-pedagogy Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[8] “The Art of Resistance: Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh has Turned into an Open Air Art Gallery”, Scroll.in (23 January 2020) https://scroll.in/article/950720/the-art-of-resistance-delhis-shaheen-bagh-has-turned-into-an-open-air-art-gallery Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[9] “India Just Had the Biggest Protest in World History: Will it Make a Difference?” by Nitish Pahwa, Slate (9 December 2020) https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/12/india-farmer-protests-modi.html Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[10] See the concept note: “The Agriforum: Gathering Contemporary Enquiries into the Agrarian”, FICA: Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, (n.d.) https://ficart.org/agriforum Accessed on 2 August 2025. Also see “Thinking with the Field: The AgriForum,” presentation by Annalisa Mansukhani, Onemai Foundation, available on YouTube (29 January 2024) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOAJa3dEi4M Accessed on 2 August 2025. For Arundhati Roy’s critique of NGO-activism in general, see her “Public Power in the Age of Empire” in The End of Imagination. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

[11] For details, see my opinion piece, “Aamir Aziz-Anita Dube Controversy Is Not About Legality or Copyright”. The Indian Express (23 April 2025). https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/amir-aziz-anita-dube-controversy-not-about-legality-copyright-9960704/ Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[12] See, for instance, artist N Pushpamala’s widely read writing published during the exhibition, “Now, Godi Artists?”, Indian Cultural Forum (19 June 2023). https://indianculturalforum.in/2023/06/19/now-godi-artists/ Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[13] Alam’s dissent came in the context of an international signature campaign calling for the reversal of KNMA’s decision to dismiss this author from the museum’s Curatorial Team, following his social media criticism of Nadar’s involvement with the pro-government exhibition. For further details, see Sharjah-based curator Sabih Ahmad’s ‘’Controversy at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi Raises Important Questions over Private Museums in Public Life”, The Art Newspaper (2 August 2023) https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/08/02/controversy-kiran-nadar-museum-of-art-in-delhi-india-private-museums Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[14] Amrita Singh, “Playing to the Gallery: How Corporate Patrons Enable the Art of Least Resistance”, The Caravan: A Journal of Politics and Culture (2 December 2023) https://caravanmagazine.in/media/corporate-patrons-enable-art-least-resistance Accessed on 2 August 2025. Also see the reportage by the same author, “Crown Jewel: Nita Ambani’s Campaign to Conquer the Public Eye”, published in the same magazine (1 December 2024). https://caravanmagazine.in/media/nita-ambani-campaign-public-eye Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[15] Gao Minglu. Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art. London: MIT Press, 2011, Chapter 9.

[16] Significant initiatives in this regard have also been undertaken by the artist Anupam Roy, in collaboration with this author, by organizing one of the first apartment art events in post-2014 Delhi—Monuments for a Hillside Evening: Art Exhibition by Arun (2018)—and, more recently, Dadri Forecast. The latter, an artistic research platform and open studio, constitutes an important experiment since it is situated at the farthest periphery of the NCR, in a backward region known for communal violence and lack of civil societies. The artist is also the co-founder of the Panjeri Artists’ Union in West Bengal, a collective engaging with the vicissitudes of the Bengali identity among others in the context of the Modi-government’s vilification of the same. For details on the latter, see, K. R. Shiyas, “From Citizens to Suspects”, The Wire (8 September 2025) https://thewire.in/law/from-citizens-to-suspects-the-dilemma-of-constitutional-morality-and-federalism Accessed on 12 September 2025.

[17] Geeta Kapur’s passionate defense of KMB is an exemplary case of this (mis)identification (in the Lacanian sense) of the region as a redemptive imaginary. See her “Kochi-Muziris Biennale: Site Imaginaries”. In India’s First Biennale 12/12/12. Exhibition Catalogue. Kochi: Kochi Biennale Foundation, 2012. pp. 132–39.

[18] Govindan Parayil, “The ‘Kerala Model’ of Development: Development and Sustainability in the Third World”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 5 (Dec., 1996), pp. 941-957. Ben Morris, “Kerala Is Still the Stronghold of India’s Communist Movement”, Jacobin (8 November 2025) https://jacobin.com/2025/08/kerala-india-communist-movement-left Accessed on 6 September 2025.

[19] KMB is organized by a private foundation in collaboration with the Kerala government’s Department of Tourism, rather than through the Department of Culture, which oversees the state’s cultural academies. Beyond its significant dependence on philanthrocapitalist agencies for funding and decision-making, the organizers’ consistent evasion of established systems of accountability—including mechanisms such as India’s Right to Information Act—has been a recurrent point of criticism. For further information, see Chandran T. V., “Skeleton of Biennale Tumbles Out of Cupboard”. In The Baroda Pamphlet, 1:4–6. 2. Vadodara: Desire Path Publishers, 2012.

[20] See “Open Letter from the Artists of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022–23”, e-flux (23 December 2022) https://www.e-flux.com/notes/510681/open-letter-from-the-artists-of-the-kochi-muziris-biennale-2022-23 Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[21] The conflict with labor unions and vendors, which need to be understood in the context of Kerala’s highly unionized and formalized work culture, is an issue which recurs in almost every edition of KMB. See for instance, “Kochi-Muziris Biennale is Back again. So is its Dirty War with Angry, Unpaid Contractors”, The Print (16 November 2022) https://theprint.in/feature/kochi-biennale-is-back-again-so-is-its-dirty-war-with-angry-unpaid-contractors/1217872/ Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[22] As the rest of the country is overtaken by various shades of right-wing populism, Kerala’s “left populism” does offer a certain reprieve. However, the transformations within the local art scene may also serve as an early warning of the region’s ongoing depoliticization and the erosion of its institutional culture. The populism of the biennale form in general and of KMB in particular is evident in the latter’s self-promotion through slogans such as “It’s Our Biennale” and “People’s Biennale”. Aligned with Kerala’s middle-class ethos, the ideological or political content of these slogans is also profoundly post-ideological and post-political, condensed into KMB’s foundational rhetoric of cosmopolitanism which I critically examined in my review of the biennale’s first edition, “Disappearing Strands of Historicity: Critical Notes on the Kochi-Muziris Biennale”. Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. XLIX No. 20 (17 May 2014) pp 55–61.

[23] Though conceived with reference to a similar “caste wall” in the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu, Mumbai-based artist Amol K. Patil’s notable contribution to the fifth edition of the KMB (curated by Shubigi Rao) indirectly evoked the memory of the Vadayampady movement.

[24] Engaging with India’s casteist gastropolitics, Dhanurdharanan’s collective exercise has recently evolved into a nomadic platform called the Untitled Kitchen, working between Kerala and Gujarat (Modi’s home state).

[25] It is worth mentioning that Unlike the United States, India is a quasi-federal system with greater power attributed to the center. This nuance is often lost, for good reasons I must say, in the debates on the autonomy of the states vis-à-vis that of the center, as recently demonstrated in the collective protest staged by dissenting states led by the government of Kerala in New Delhi. For details see “Indian Democracy being Crippled by Centre’s ‘Union over States’ Mentality: Kerala CM at Delhi Protest”, The New Indian Express (8 February 2024) https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2024/Feb/08/democracy-in-india-being-crippled-by-centre-s-union-over-states-mentality-kerala-cm Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[26] Long considered one of the most militarized zones in the world, the Himalayan region disputed between India and Pakistan came to global attention primarily for three developments in the last decade: the massive popular protests following the killing of Kashmiri militant-leader Burhan Wani by Indian security forces; the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 and 35A for fully annexing the territory despite the local resistance and the UN resolution for a plebiscite, which was followed by communication blockade and political arrests for years; and recently, the Pahalgam terrorist attack targeting non-Muslim tourists apparently for sabotaging India’s claim of bringing Kashmir to the mainstream as a center of tourism and real estate business (thus exposing the state’s settler-colonial interests comparable to that of Israel). Leading to intense military conflict between India and Pakistan, the Pahalgam attack also triggered a wave of anti‑Muslim violence across the country, further bolstering Modi’s image as the savior of Hindu pride. The Indian authorities in Kashmir also banned 25 books, including novelist Arundhati Roy’s Azadi: Freedom, Fascism, Fiction, the late constitutional expert A. G. Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute, and the Verso-publication Kashmir: The Case of Freedom, following the familiar fascist script.

[27] See the photo-essay featuring Hassan and Ahmad, “Blood and Thunder: Performance Art as Resistance in Kashmir” by Shahid Tantray, The Caravan: A Journal of Politics and Culture (1 December 2024) https://caravanmagazine.in/arts/kashmir-resistance-art, Accessed on 2 August 2025. Ahmad, along with Janees Lankar, is the founder of Shikargh Collective which seeks to explore the political potentials of Bhand Pather. For an interview with Kashmiri Cabbage Walker, see “Walking A Cabbage On A Leash In Kashmir”, Homegrown.co.in (8 June 2021), https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-creators/the-art-and-politics-of-walking-a-cabbage-on-a-leash-in-kashmir Accessed on 2 August 2025.

[28] Founded by three women photographers—Nawal Ali, Ufaq Fatima, and Zainab Mufti—Her Pixel Story seeks to create a platform for women and non-binary photographers, by conducting photo walks, collaborative projects, workshops, and reading sessions. The collective was formed as a response to the otherwise critically acclaimed photo book Witness: Kashmir 1986-2016 (edited by Sanjay Kak in 2017), which showcased the works of nine Kashmiri photographers, all of whom were men. Another important Kashmiri woman photographer in this context is Pulitzer Prize winner Sanna Irshad Mattoo (discussed in The Caravan story, “Playing to the Gallery”, mentioned above).

[29] Quoted from “Art Collectives as Trojan Spaces: Re-imagining Gatherings in Kashmir” by Salman B. Baba in Heck: Call #2 (July, 2025) pp 28-41. https://hekh.in/storage/work/assets/pdfs/Call2-2.pdf Accessed on 24 September 2025.