Acts of Refusal: Performance, Grief, and Collective Dissent at the ISP

Leila Abdelrazaq

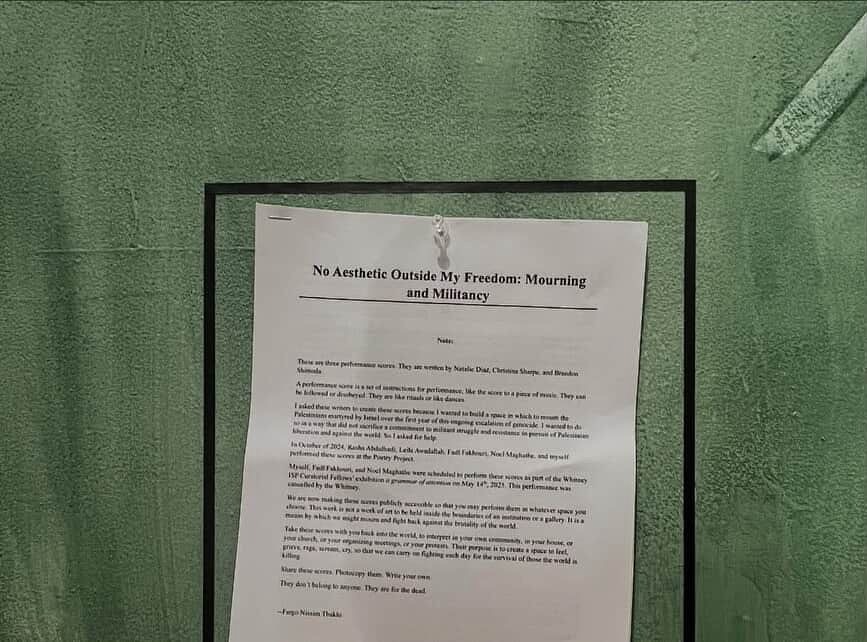

Throughout May of 2025, the Westbeth Gallery in Manhattan’s West Village was slated to display the works of the Studio Cohort in that year’s Independent Study Program (ISP), a decades-old initiative of the Whitney Museum. Instead, the exhibition, entitled Prototype, was transformed into what former ISP associate director Sara Nadal-Melsió described as a place of “haunting”: nearly all of the artworks had been removed from the gallery, with the notable exception of a film that Studio Cohort member Ash Moniz created in collaboration with Gazan artists and musicians about the Gazan rock band OSPREY V, entitled [Inaudible]. The film played on loop in the space, reverberating through the mostly-empty gallery. Papers containing scores for the recently-cancelled performance No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom: Mourning, Militancy, and Performance, which had been solicited by the ISP’s Curatorial Cohort for inclusion in their exhibition a grammar of attention, were tacked to the wall. There was a QR code on the back of the scores and bold letters reading: “DO SOMETHING.”

The artists, writers, and curators at the ISP had shut down their end-of-year programming in solidarity with the people of Gaza, following months of unprecedented surveillance of the historically independent program on the part of the Whitney, which had resulted in the Museum’s unilateral cancellation of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom. The performance was meant to explore the generative capacity of collective mourning to incite political action against genocide. On the day that the performance was cancelled by the Whitney–two days before it was scheduled to take place–the genocide was on its 582nd day.

For participants in that year’s ISP cohort–the very first containing a vast majority of women and non-binary cohort members, and the first that did not implicitly require cohort members to have a connection to an alumnus of the 56-year program–questions of war were not theoretical. Many of the participants or their loved ones had been directly impacted by armed conflict. And just weeks after the Whitney’s repressive actions against its own program, which generated a media frenzy, the lead videographer for [Inaudible] and Moniz’s primary collaborator on the film, Ismail Abu Hattab, was murdered by the Israeli military while working at Al-Baqa Cafe in northern Gaza. The airstrike that killed him on June 30, alongside over 30 other Palestinians at the popular seaside cafe, which had served as a favorite place for artists and journalists to gather, work, and access WiFi, also took Abu Hattab’s hard drive with him, destroying a rich archive of Palestinian life in Gaza.

The cancelled performance, set to be staged by Palestinian artists Noel Maghathe, Fadl Fakhouri, and Fargo Tbakhi, featured scores written by Natalie Diaz, Christina Sharpe, and Brandon Shimoda. The performance demanded that audiences not only bear witness to Palestinian pain, but help hold it, and to let the act of this shared holding lead them to political action. This demand is an especially important one in an age of voyeurism, where Palestinian pain is produced and reproduced for widespread consumption to seemingly no end. In many ways, we can understand the ensuing actions of the three ISP cohorts (across areas of Critical Studies, Studio, and Curation) and its associate director as a response to the call that the performers made in staging the piece. That call represented just one of many, which together form a cacophony of voices across the globe demanding that the world unmake itself and all of its structures of violence, towards liberation and an end to the genocide.

The compounding acts of solidarity that took place following the cancellation of the performance represented a political commitment to standing in solidarity with the people of Gaza, and it had real consequences for the participants: in response, the Whitney paused the ISP, cancelled its 2025-26 iteration, and ousted its associate director, who had only recently been appointed. We have much to learn from what took place at the ISP in 2025. The acts of refusal and negation that the ISP participants took part in, collaboratively and in conversation with artists in Gaza and the performers of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom, constituted a kind of insurrection against the Whitney, resulting in something that resembled what Tbakhi termed in his 2023 essay “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide” a kind of “aesthetic terrorism,” one that “hijacks” neoliberal arts spaces towards “principled solidarity with the long cultural Intifada.”[1]

To Love Palestinians Wholly and Completely

The first iteration of the No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom was commissioned by Jewish Currents, and staged by The Poetry Project on October 14, 2024. While the scores were performed by a cast of all Palestinian artists, they were notably written entirely by non-Palestinians who come from lineages of resisting genocide, repression, and racialized violence in various ways. During the first iteration of the performance that October evening, Maghathe sat on the wooden floor of The Parish Hall at St Mark’s Church, their body curled inward, and whispered, “Tell me what to do.” What does it mean for a Palestinian to look into the eyes of another and ask them what to do, particularly in a moment where individuals with no interest in Palestinian life seek to impose control on their fate? It implies a deep kind of trust, and it demands that those brought into the fold answer for and help hold Palestinian pain. This is in essence what had been asked of Diaz, Sharpe, and Shimoda when they were approached to write the scores for the performance: to offer a prayer, a ritual, to draw from their own legacies and traditions so that we might learn together about how to move through the unfathomable.

Before the start of that first performance, reading from his phone, Tbakhi delivered a call to the audience that requested they do the same if they wished to watch a group of Palestinians quite literally perform their pain. Tbakhi insisted that in order to join in this act of collective mourning, audience members must love Palestinians (“You may only remain in this audience if you love Palestinians wholly and completely…if you love us while we are alive, and when we are dead. When we are fighting for survival, dignity, land, return, real and sustainable life using any and all methods available to us.”) And love for Palestinians, Tbakhi insists, is a verb, one that must be embodied through a commitment to dismantling the states and systems designed to exterminate us (“You may not remain in this audience if you believe in Israel in any incarnation, given its ontological structure as a continual process of extermination, dispossession, and daily cruelty.”) Nor may this love be predicated on Palestinian performances of respectability (“You may not remain in this audience if it is important to you that we condemn violence.”) Finally, Tbakhi insists that in order to end the genocide, in order to attain Palestinian freedom, the entire world, as it currently exists, will need to be unmade. In this context, collective mourning becomes a political act, and one that demands action.

“You may not remain in this audience if your heart is closed to the ending of the world. …If we are to mourn the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians martyred in the long struggle for dignity together, here, in public, then it is imperative that we understand what that obligates us to do.”

Tbakhi is influenced by Brazilian theatre practitioner and theorist Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, in particular, Boal’s approach of denying the audience catharsis as a method to incite political action. “Palestine requires that we abandon catharsis,”[2] writes Tbakhi in his “Notes on Craft”. No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom is very clearly an effort to implement this strategy. It involves audience members directly in rituals of mourning, like the collective scratching of lines onto papers using charcoal (incidentally, one of the drawing tools that is currently most available to the people of Gaza). These marks, appearing as smudged and increasingly abstracted tallies, come to line the walls of the room. Their residue leaves its traces on the fingers and palms, and participants take these marks with them. The performance also produces a discomforting sonic experience throughout, preventing the viewer from drifting into the lull of aesthetic pleasure: Fakhoury, wearing a pair of tap shoes, snaps their feet against the floor to produce an arrhythmic shuffling and clapping that drowns out their own monologue. Tired bodies produce strained amplifications of human breath: panting, gasping, moaning, weeping, hissing. But perhaps most crucially, the piece fails to end. As the lights go up, the performers sit together on the floor, draping one-another in a knotted chain of patterned scarves in their interpretation of Diaz’s second score, “Ash can make you clean, as alkaline as it is a grief,” which instructs the performers to build a pyre together. It is this core of the performance, the way it denies the viewer that Aristotelian catharsis which would have allowed them to walk away feeling as though they had done something for Gaza by watching a performance in Manhattan, the way the piece categorically refuses congratulatory applause, the way it draws critical connections between Palestine and other global anti-colonial and liberatory struggles, and the degree to which the performers directly implicate both the audience and the Museum itself, that the Whitney could not allow in its space. To do so would have been to legitimize the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, recognizing it as the anti-colonial struggle that it is. And, it would have demanded a serious reckoning with the Whitney Museum of American Art’s culpability in Palestinian genocide in Gaza.

Instead, the Whitney used Tbakhi’s introduction to the October 2024 performance as a pretext to cancel it entirely, saying it went against their “community guidelines.” That the Whitney chose to interpret Tbakhi’s earlier call not as an invitation to practice deeper solidarity with people actively enduring a genocide, but instead as a foreclosure, speaks volumes about their values and positionality as an institution. But this comes as no surprise–multiple board members have financial ties to weapons manufacturers that are actively supporting the genocide, as well as the state of Israel itself. Most notable among them are Nancy Carrington Crown and Leonard Lauder. The Crown family has major investments in General Dynamics, a weapons manufacturer that has supplied munitions and military technology to the Israeli military for over two decades. And Lauder’s brother has served in leadership roles at Zionist institutions like the World Jewish Congress, as well as the Jewish National Fund which has been actively involved in violent Palestinian dispossession for over a century.[3]

Additionally, the Whitney’s preoccupation with “imagery of violence” as a way to deflect attention from real acts of genocidal violence also points to a larger issue, the conditions on which Palestinians are allowed to speak or exist in public space. Mohammed El-Kurd writes about this phenomenon as “the politics of de-fanging.” In order for the Palestinian to become human, he writes, we must be “polite in [our] suffering.” The project of humanization “restricts the range of sentiments and emotions we are permitted to express openly, the values, ideologies, and affiliations we can claim without retribution, and even searches in our thoughts and fantasies, in our inferred intentions and ignorances, and in our tacit beliefs for attributes to censor and reeducate.”[4] Within this paradigm, conversations about Palestine are occasionally permitted in the institutional space as long as the museum determines that the work might be made docile, framed as part of a conversation around a ‘complex issue.’ In these instances, Palestinian art or speech may be permitted by institutions, insofar as the work might be used to legitimize their own position, which seeks to validate itself through displays of ‘inclusion.’ This type of conditional inclusion works to obscure the structural violence that simultaneously silences or works to “de-fang” Palestinian speech. No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom was staged with an awareness and very intentional refusal of this regime, which seeks to control and modulate Palestinian dissent.

Following the cancellation of the show, the performers were asked by ISP members if they would like to stage it elsewhere. In line with the refusal enacted throughout No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom–the performers’ pointed failure to comply with expectations of respectability, their refusal to allow Palestinian mourning to be “de-fanged,” to be cleansed of its rage–they declined. The artists were instead clear that they wanted the cancellation itself to be seen, to draw attention to the systematic silencing of Palestinian voices amidst the genocide. They aimed to make visible the Whitney’s tacit endorsement of gruesome violence against Palestinians in Gaza. This in turn catalyzed cascading acts of refusal and direct action. This collective refusal, on the part of the artists involved, to participate in institutional violence against Palestinians, their refusal to be absorbed by the museum and its complicity in genocide, left the Whitney with little to do but to cannibalize itself.

Refusing Structures of Repression

When Catalan writer and educator Sara Nadal-Melsió began to restructure the ISP as its newly-appointed associate director, she immediately began working to dismantle long-entrenched structures behind the 57-year-old program, which had for decades privileged those with connections to famous alumni. That year’s cohort, across the areas of Curation, Studio, and Critical Studies, was the most international in the program’s history. It was also the first time in the program’s nearly six-decade history that the cohort consisted of a large majority of women and non-binary participants. Nadal-Melsió worked to build an infrastructure for critical and courageous creative and intellectual inquiry that would eventually provide those involved, including the associate director herself, the support required in order to take risks and political action. The majority of the cohort members did not come from organizing backgrounds. And yet, together, they built and implemented an iterative and escalatory political strategy that galvanized action and spread political awareness not only amongst themselves, but also in the broader New York City community.

It is for this reason that we might seek to study and understand the events that unfolded at the ISP in 2024-25 as one among many contributions to the “long cultural Intifada.” In this case, the actions took place from within one of the empire’s foremost arts institutions. How did the 2024-25 ISP cohort members work to divest themselves from the very structures that undergird the Whitney Museum of American Art and its work as a mouthpiece for American empire, even while operating in relation to the Museum?

It required a radical restructuring and dismantling of the norms of the institution of the ISP itself. And Nadal-Melsió’s efforts, alongside the efforts of cohort members, went much deeper than a simple change in the participant selection process or a demographic shift. The structure of the program itself was redesigned to become an experiment in creative, critical, and cooperative community building. The 2024-25 cohort was housed for the first time in a new permanent home at the Roy Lichtenstein Studio in Greenwich Village, and cohort members worked to make it theirs. At the suggestion of Critical Studies participant Adrienne Oliver, they installed a collective ofrenda, allowing members impacted by war and loss to grieve together, and to include and hold space in the work for those who had left this world. They cooked meals collectively, reducing the program’s reliance on the service economy. Cohort members didn’t simply meet for seminars with invited guests, as per the traditional model. Instead, guest speakers and presenters were brought in to be in collaborative dialogue with ISP participants. They hosted hands-on workshops and engagements with cohort members and ate meals together. Studio visits with guests were assigned based on a lottery system, and members who did not get to participate in a particular studio visit were invited to cook and host a meal for the guest, which everyone was able to join. Rather than arranging visits to the largest and most powerful arts institutions in New York City, the programming prioritized connecting with important alternative, grassroots, or artist-run spaces, many of whom have made up the fabric of New York City’s creative communities for decades, like The Poetry Project, Brief Histories, and Giorno Poetry Systems (GPS). Professionalization was eschewed for experiments in more insurgent practices, with the group producing zines and other self-published materials in place of catalogues for their final projects. The program was designed to be continually reflexive and growing, with Assemblies and Community Fridays acting as a weekly space for ISP participants to revise and refine their collectively community agreements and think together about the labor of community building. And while during the 2024 ISP Critical Studies symposium the ISP’s director had advised against the use of the word “Gaza” in the program, Palestine had been a recurring and intentional part of the conversation in the 2024-25 cohort since its beginning.

Together, these initiatives worked towards creating a more horizontal ISP community, one that was emergent and built collaboratively by its participants. And the Whitney took notice of the changes. Even before the cancellation of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom, ISP participants shared, the Whitney was simultaneously impeding on the program’s flagship “independence” while failing to provide institutional support to cohort members who needed protection in an increasingly dangerous and hostile political environment. The Museum began to place undue levels of scrutiny on the work of program participants, surveilling their projects and activities in unprecedented ways, reviewing all of the work that the cohort members were producing, and removing program announcements from the e-flux website to reduce visibility, all on the pretense of “security.” Yet when the ISP approached the Whitney to request meaningful protections and legal counsel for program participants who might have trouble with the new administration, they refused to help. Instead, the ISP had to spend time compiling their own dossier of resources, gathering materials from local support organizations like We Make the Road and CLEAR (Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility) at the City University of New York School of Law.

This pattern of simultaneous surveillance and lack of support culminated when Moniz was attacked on the New York City subway by a group of Zionists in an act of anti-Palestinian violence for wearing a kuffiyeh. That day, Moniz had been on their way to meet with curators and administrators at the Whitney, who had demanded to meet with cohort members to review their work. Moniz described the surreal absurdity of walking into the meeting crying, having just washed blood off their face after being assaulted for their visible proximity to and support for Palestinian life, and being asked to make a case as to why Gazan voices needed to be uplifted in their piece. Shortly thereafter, on May 12, the Whitney made the unilateral decision to cancel No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom.

What ensued was a cascade of strategic and accumulating political actions. These actions were not made possible because the ISP cohort spent time engaging in organizing or studying Palestinian history in particular. Rather, it happened because they had spent time building community with one-another and committing to experimentation through a variety of creative practices and ongoing critical conversations.

Immediately following the show’s cancellation and the decision by the performers of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom to refuse to perform, one by one, each of the ISP’s three cohorts released statements that were accompanied by tangible acts of refusal which mirrored and expanded on those performed by Fakhoury, Maghathe, and Tbakhi. These statements, which were issued one after another in succession over the course of about a week, were not replicative in nature, but cumulative. Each provided a distinct lens on the situation and added to the one before. Together, they formed a cacophony of perspectives and voices from across the different cohort areas. Like the cohort members themselves, the statements did not represent monolithic thinking, but they were unified in a core, collective call. That these statements not only functioned in dialogue with one-another but were also tied to concrete actions distinguished them from the traditional statement format, which provides a unified political platitude and shakes its fist at power in the absence of action.

The Curatorial statement came first on May 13, alongside the decision on the part of the performers not to stage the piece at a different venue. Next, the Critical Studies cohort released a statement on May 17, in which they announced the cancellation of their symposium. This was followed by the Studio Cohort, whose statement on May 19 coincided with a majority of artists removing their work from the show, dismantling and reinventing their exhibition, and turning the gallery space into a site of protest that the Westhbeth condemned as “ugly.”

While Moniz wanted to remove [Inaudible] in protest, when they explained the situation to their collaborators in Gaza, the artists were all insistent that the piece should remain in the show. Moniz honored their wishes. The film’s name had come from its central message, that “Palestinians are completely silenced…no matter how loud they scream, no one is listening.”[5] In the decision to remove nearly all works except the one centered on Gazan voices, the artists in the Studio Cohort collectively inverted the normative tactics used to silence Palestinian voices, in which violence and censorship result in the absence of those voices, and the negative space that this produces is intentionally obscured and invisiblized. Instead, the show quite literally turned up the volume on Palestinian narratives by making visible the negative space produced by those who refused to show work in solidarity with Palestinians, and then centering a piece that shares the experiences of Gazan artists. Additionally, in leaving [Inaudible] up, the exhibition had to remain open. Studio Cohort members were still required to show up to the now mostly-empty space each day to gallery sit. This experience, Moniz said, was one of the most moving and generative experiences that year. The show brought in many people from around the neighborhood who expressed that they did not normally visit arts spaces, but wanted to understand what was going on. Some people would stay for hours to talk, and the space became a site for political education and engagement. What the studio cohort ultimately produced was an exhibition that represented collaborative and accumulative acts of refusal as collectively agreed upon by ISP cohort members, the No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom performers, and the Gazan filmmakers and musicians who had worked on [Inaudible]. Some visitors broke down into tears while viewing the exhibition. In this way, Moniz reflects, the vacant spaces in the exhibition, coupled with the tacked-up scores and the voices and story of the Gazan musicians in [Inaudible], had a much more profound impact on attendees than any single piece of work in the gallery ever could have.

Immediately following the release of the Studio Cohort’s statement, Nadal-Melsió posted her own statement in support of the cohort members and condemning the Whitney’s censorship. In issuing this statement, Nadal-Melsió had committed a cardinal sin as a director-level arts educator: she had publicly, and in no uncertain terms, aligned herself with the artists, writers, and art workers that make up the lifeblood of the institution. Institutions cannot allow this to happen. They must swallow educators, especially director-level staff, into themselves. The task of an arts educator operating within an institution is to work in service of the institution itself above all else, in order to produce a structure that functions separately from the community of artists on which it depends. It is this structure that Nadal-Melsió threw into jeopardy. Her statement functioned as a discordant act that refused and dismantled these normative infrastructures.

Finally, on the evening of May 23, over 80 community members from around New York City flooded the lobby of the Whitney to disrupt the Museum’s Free Fridays programming. They unfurled banners over balcony railings and swept them across stairwells. The banners highlighted the ways that the Whitney and its board members both fund and profit directly from the genocide in Gaza, and bore slogans like “War Crimes Sponsored by the Whitney.” As the organizers began a people’s mic style takeover of the museum space, the response of attendees at the Free Fridays event was moving. Museum-goers joined in the call-and-response chants, helping to amplify the words of the organizers. Some asked to help hold banners. All 650 of the informational pamphlets that the organizers had printed, styled after the Whitney’s official museum brochure and titled “The Whitney Museum of American Genocide,” were quickly taken. Immediately after the protest started, the Whitney locked the doors to the museum, trapping hundreds of people who had been lined up to attend the evening’s programming outside. They then joined organizers who had also been locked outside in a second protest, chanting together at the doors. The action went on for nearly two hours before the Whitney called the police to help disperse their own visitors.

It was just days later, on June 2, that Nadal-Melsió was fired, the 2024-25 program paused, and the 2025-26 program admissions process cancelled.

The 2024-25 cohort is already being erased from the history of the ISP. The Whitney has reportedly begun to plan for the next iteration of the program, and is doing so in ways that eschew feedback or input from the 2024-25 cohort and those that made it possible. And participants from this past year haven’t received any of the “benefits” that ISP graduates normally receive, such as a life-long membership to the Whitney. In many ways, the 2024-25 cohort did something that no other cohort had done before: they took the mission of the ISP seriously, not as an elite brand or prestigious club, but as a space for radical, critical, and collaborative work. The seriousness with which the cohort took that charge resulted in political action through the collective refusal to participate in a creative economy that is predicated on the destruction of Palestinian life. In so doing, they also answered repeated calls for direct action against complicit arts institutions that Palestinians have been making for decades, long before the genocide began.

Opening Our Hearts to the End of the World

The final event that the ISP cohort members attended that year was a fundraiser for Gaza and screening of [Inaudible] at Giorno Poetry Systems. Following the screening, event attendees had the opportunity to speak with the Palestinian musicians featured in the film, who are based between Gaza and Cairo. The panel members insisted: “Talk to us as artists. We are musicians.” Those words, spoken into the eye of a camera and beamed across borders into a darkened room in New York City, concluded the ISP programming in 2025. Two days later, the Whitney dismantled its nearly six-decade long flagship program, which former Whitney Director Adam Weinberg had previously called a “conscience of the Whitney.”[6]

The museum relies on the myth of the individual, who values and prioritizes self-preservation above all, to help protect larger institutional infrastructures which work to supersede the communities that constitute them. It is this dynamic that the 2024-25 session of the ISP worked to dismantle. Instead, all of the artists, writers, and curators involved, from Gaza to New York City, strategized around the power they held as a collective, and mobilized strategic acts of refusal and divestment from the institution itself as a powerful political tool, one that acts not as a foreclosure, but that opens up multitudes of possibilities for different ways of being as an artist, that amplifies the voices of Gazan artists, and that imagines alternatives to an art world that sustains itself with genocide and violence. Among the banners displayed at the May 23 demonstration was one that read “Another Art World is Possible.” What might this world look like? For Nadal-Melsió, her brief tenure at the ISP affirmed to her that the future is counter-institutional. In order to survive, we need to build the communities, the solidarities, and the trust, outside of and against institutions, that will provide the alternative infrastructures required to propel us into increasingly braver political action. If we wish to end these multi-layered violences, we have to be willing to disrupt their structures everywhere we are, and everywhere we find them, until the powers that be have nothing left to destroy but themselves. The relevance of these institutions will only continue to diminish as the ways in which they are aligned with and help uphold structures of violence is revealed. While these dynamics are in no way new, the current political moment has brought these realities into starker relief. This approach will seldom be neat, will at times be painful, and will never produce ideological monoliths. And, if truly meaningful, this work will always come with real consequences.

It is here that we return to the pyre. As the attendees of that first staging of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom filed out of the room, their collective footsteps on the creaking wooden floor together sonically reproduced the crackling of a fire. The performers remained sprawled there at the center of the space, in that hearth that they formed together. What began as the reenactment of an all-consuming blaze had transformed into a series of gestures of love and care: each performer taking a turn to wrap another in the chain of scarves-as-flames, draping the knotted fabric across one-anothers’ shoulders, or around their chests. Might we think of what occurred at the ISP as an extension of the solidarities that the show demanded, driven as it was by collective mourning, by grief, by rage? Might we imagine that the collective ofrenda in the space called in spirits that reminded participants of the political responsibility that their absence, and the holding of that absence, requires? Might we hope that all of the attendees the evening of that first performance of No Aesthetic Outside My Freedom carried a flame with them back out into the October night, each with its own destination? That the pyre built there was just one among many, and that others too have allowed the flames of their grief to guide them? One takes a flame to the symposium papers. Another flame empties the gallery. A flame at the doors of the museum. Flames to light the way for the flotillas. Flames, erupting here and there, taken from and forming new pyres, outside of and beyond, until at last, we find ourselves together in the terror of that smoldering emptiness, left only with one-another and all we might create together, in unbound possibility at the end of the world.

Leila Abdelrazaq is a Chicago-born Palestinian writer, artist, and cultural organizer. She is the author of the graphic novel Baddawi (PM Press, 2015), and she writes on Palestinian culture, political imaginaries, and futurity. She is a Ph.D. student in Art History, Theory and Criticism + Art Practice at UC San Diego.

Notes

- Tbakhi, Fargo. “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” Protean Magazine, December 8, 2023. https://proteanmag.com/2023/12/08/notes-on-craft-writing-in-the-hour-of-genocide/ ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- For more history of the JNF, see: Massad, Joseph. “Jewish National Fund: A century of land theft, belligerence, and erasure,” Middle East Eye, Feburary 1, 2023. https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/colonial-chutzpah-jewish-national-fund. ↑

- El-Kurd, Mohammed. Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal. Haymarket Books, 2025. Pp 38. ↑

- “Ash Moniz Speaks With The Gazan Rock Band OSPREY V,” Giorno Poetry Systems. https://giornopoetrysystems.org/222-bowery/events/ash-moniz ↑

- Whitney Museum of American Art. (2022, December 6). Independent Study Program @ Lichtenstein Studio. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-nCiAzBqDY0 ↑