Identity Curator: Peter Doroshenko and Keeping the Ukrainian Museum in New York Truly Ukrainian

By Valeria Radkevych

Peter Doroshenko, born in Chicago to a family of Ukrainian immigrants, was appointed director of the Ukrainian Museum in New York in 2022. He brought a bold curatorial vision rooted in cultural reclamation and historical justice to a cultural institution born through immigration dynamics. This conversation explores the groundbreaking exhibition on Volodymyr Tatlin and the broader project of decolonizing the avant-garde – reframing canonical figures often misattributed to the Russian tradition. Doroshenko positions the museum as both a mirror and a catalyst: challenging inherited narratives, bridging the diaspora with contemporary Ukraine, and expanding the understanding of Ukrainian identity through art. The museum’s upcoming program reflects this mission: Ivan Frolov/Boris Mikhailov and Bonds of Affection (Sept–Dec 2025); Creative Pale (Jan–Apr 2026); Diaspora and Earth (May–Sept 2026); and, marking its 50th anniversary, Ilya Repin: Steppes and Alla Horska (Sept 2026–Jan 2027). These exhibitions collectively trace a path through modernism, displacement, memory, and resistance, offering a vital reexamination of Ukraine’s cultural legacy in a time of war and transformation.

Valeria Radkevych:

I wanted to start with the question: why Tatlin? What is there about him that you decided to show in the Ukrainian Museum, which is a Ukrainian cultural institution? Why did you choose his personality as a focus?

Peter Doroshenko:

Even before the war started three years ago, I was already thinking about it all because I’ve been involved, I visited, I lived, and I started museums in Ukraine. I’ve been thinking about decolonization and the war. What I thought would take fifteen, twenty-five, or thirty-five years to do, the war has accelerated in two years, and that is something that is not talked about enough. The whole aspect of Ukraine, switching to speaking Ukrainian, Ukrainians seeing themselves as Ukrainian, the aspect of nationality, history, culture, their heritage, all changed basically in a few months. And it is not just in Ukraine; it is also in the diaspora, and people who have heritage or lineage from Ukraine appear in every conversation. I will go to an opening or a lecture here in New York, and everybody says, “Oh, I am Ukrainian,” “I am part Ukrainian,” “My grandparents came from Odessa or Kharkiv. I always thought that was Russia. Now I found out it is Ukraine, so I can’t wait to come to your museum.” “I’m learning as much as I can about Ukrainian because both my grandparents came from Kyiv,” and so on.

I want to say that so much has changed that has always been in my mind about decolonization, and there is so much to do. The mountain is so big because everybody who is important has been labeled as Russian. This is part of a formula, and it is still happening today. Anybody important, anybody who makes significant contributions to culture or art in the East, is immediately labeled Russian, and it happens through lies. It happens through propaganda. It happens through manipulation, and it continues happening today. We see it in the different cities that they occupy, and where they empty museums. For example, if somebody was born in Kherson, they were labeled as Russian. How could that be? So, for me, it was something that I have been thinking about for quite a long time. But when I brought that topic up to even Ukrainians, that was like talking about Mars. It was like an outer space conversation, the whole aspect of decolonization. Now it is something that we have to do. This is the time to set history straight. And we started this process through our exhibitions. The first exhibition was, in a big way, Alexandra Exter. Now it is Volodymyr Tatlin. The next exhibit will be Ilya Repin, at the end of next year. And then after that, Vasil Yermilov, and then Malevich afterwards.

So the thing is, these are the bigger names, but to make it up the mountain as much as we can, we have to tackle the bigger names. Even though that is a bigger job, it is more stressful. For a small museum, it is a lot to do. But unfortunately, that is what people understand: big names. Then we can kind of expand that to others, to other artists working in different fields, through installation or whatnot. So these are the things that are extremely important, and that’s why we started with Exter and Tatlin.

VR:

Tatlin is a very mysterious character. So, how do you tackle him as a Ukrainian soul? In the catalogue, you say that his Ukrainian heritage and all the folk culture that he absorbed in his life influenced his art, and consequently also influenced people that he taught and that were around him, and the artists that were to come later, who were influenced by him. What do you think exactly that influence was? How do you think that influence is incarnated in his art, or in the art of whoever was following him, because he was a constructivist, and just like Vasyl Ermilov, for example, it is hard to see this Ukrainian cultural milieu in the constructivist art. So, when you talk about the folklore and the craftsmanship that he absorbed as a child, maybe, how do you think it then materialized in his art later?

PD:

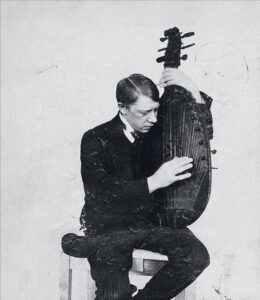

First of all, Tatlin, like Malevich, even though they were friends and then later became enemies, both started with a domestic kitchen, and it is the pysanky, the Easter eggs, the vyshyvanky, all of these national objects. And that was the starting point. And then, you know, for Tatlin it was music, the bandura. And then using Bandura as almost the first artist who used photography and pictures of himself to progress his career and his work. I mean, he was probably the first Cindy Sherman (laughs). And so, you know, there are almost no photographs of Tatlin. There are only about nine, nine or ten that I have ever found. And so, out of those nine or ten, there are three of him playing the Bandura. And they are all staged.

VR:

And he is also pretending to be blind in those pictures.

PD:

Exactly. So the whole thing is there, as you mentioned, being blind like a kobzar. There is a performative component, the theatrical one. He was always involved in theater, and that is why he was friends with Exter; that is what they shared, because theater for them was like television and the internet. They knew that they could connect to the masses and to connect to common people through the theater. What he was interested in was, once again, harnessing those early folk things.

And this is very interesting. A lot of this folk art created intense dialogues, both for Tatlin and others, mostly for Malevich, but others from Ukraine, too, who started thinking about critical theory. And you know, if you think about it, they handled it all in different ways. Malevich was more on an academic level. For Tatlin, it was more about focusing on his work and using it as a parameter for where he felt comfortable, where he excelled at with his ideas, and for others, it goes from there.

What I do feel is that he was the first conceptual artist, because he was more focused on ideas and talking about the different kinds of aspects, not only of his work, but other works that he was interested in, than anybody else at that time. I mean, if you think about it, he started thinking about and doing these things in 1910, 1911. That is super early. That is way before the Germans or Italians or the French, but once again, he did it in his own way, and he was not very good at keeping journals or writing anything. He was actually awful at that. He liked reading, and that’s something he did quite a bit, but the reading that he did did not go so far away from, once again, Ukrainian heritage. I mean, Mykola Gogol was his favorite author, and Ivan Franco, and Taras Shevchenko until his death. He created his own dialogue in his mind, in his own life, by limiting what he absorbed. But he took it to the highest level intellectually.

VR:

So you talk about the critical theory that Malevich developed in an academic way. And that is quite clear. But how do you think Tatlin went into this critical theory? Can you elaborate on that?

PD:

You know, obviously, he was very interested in it all, starting with the 1917 revolution in Moscow, and that is where he found a thread with politics. Because once again, he was doing paintings. He was doing what was kind of the norm. Not that he was very political, not that he used it in any kind of unique manner, but it was after the revolution that, for the first time, he found that politics could turn things around. Where the Bolsheviks used cinema and art as a virus to connect with the masses, Tatlin used politics as a way to get to the people. He kind of flipped the formula, while never completely buying what the Bolsheviks were selling. But he found it to be an important tool and political atmosphere, and what was going on at the time, the different committees, was a way to propagate his ideas and his own utopian vision for what life should be.

VR:

I was always curious about the Monument to the Third International because that is something that I studied as part of 20th-century art history. And this is where people normally meet Tatlin for the first time. They do not meet his Letatlin immediately, or they do not know about the stork that he kept at his home. They do not know about banduras and his performances, but they meet the Monument to the Third International, which sets him in the framework of a very political socialist art. And while right after the revolution, there were quite a lot of socialists also in Ukraine, because Ukrainians believed in socialism, it was something that they thought was promising them freedom, finally, until they discovered that it was not. So they built the Monument to the Third International. It is a very direct but complex question. How do you interpret it? What do you think about this? I would like to have your interpretation of this artwork, because this is something that everybody sees as the first thing when they meet Tatlin for the first time.

PD:

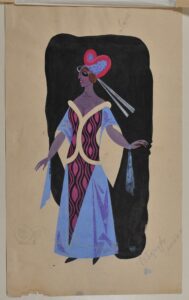

Well, once again, for me personally, it was theater. For him, it was a prop or a stage, and it had less to do with architecture or politics than everybody gives him credit for. I think it was a way to win a prize, which he did. There was never any money to build it, and everybody knew that. I am sure even Tatlin knew that there were never enough resources to build that tower. So for him, I think it was a great exercise, which it turned out to be, to raise his profile, which it did. Tatlin always had to have students around him. There was his success and the leverage, too; without each other, they would not have achieved half of what they did. And so for him, I think it was also a way to buttress or support his teaching and to get more involved and to create almost a group idea, or like a commune of ideas, and then, secondly, to create something spectacular that he later did in theater. And I think once again, it is always part of that kind of timeline and the same set of ideas. So I see it as very similar to what Alexandra Exter did with costumes and her students did with the stage; that for Aelita, made in 1923, it is all part of the same kind of system of theater.

VR:

So you are saying that it is very politically charged when it should not be, actually?

PD:

Correct.

VR:

That is very interesting.

PD:

And I think only later, actually much, much later, only starting in the late 30s, under Joseph Stalin, did the Bolsheviks start positioning it as a big communist marker. And I do not think it was that. I think, yes, it got him notoriety. Yes, there was a revolution going on. Yes, the Bolsheviks used it as far as a propaganda tool as they could, but it was only later that art historians or people at institutions in the Soviet Union positioned it to the political level as it is now.

VR:

In fact, people like Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich, and Alexandra Exter were pretty much forgotten in the Soviet Union, forcibly forgotten because any kind of formalist research was simply prohibited in 1932 when the decrees on socialist realism were signed. At first, they referred to literature, but then Joseph Stalin said to just apply those rules to everything else. So this is what I wanted to ask next, to move a little bit away from Tatlin and the constructivists. What do you think is the meaning of the Ukrainian avant-garde? We are not talking about the Russian avant-garde anymore at this point, because we are in the decolonizing stage. And so, the Ukrainian avant-garde, where do you see its reflection or its influences in Ukrainian contemporary art, or the art that immediately follows independence? You worked in Ukraine as well for a long time, so I’m sure you got a taste of that.

PD:

First of all, there was definitely a Ukrainian avant-garde. There was an avant-garde in Moscow. So it is hard to call it just Russian, but I think lazy academics and people who are confused about geography and history do not know the difference between Ukraine and Russia. So it is a lot easier to label something Russian, you know. So that is number one, and then there are those who were living in Moscow. I mean, once again, the top two or three artists happen to be Ukrainian, born in Ukraine, of Ukrainian heritage. So one could say that the avant-garde was either Ukrainian or, when it was in Moscow, was built on the bones of Ukrainians, and that is something we never discuss, because, once again, everything in Russia has to be Russian. I get that. But I think the avant-garde that did exist, and there, you know, there was a small one also in Warsaw in Poland. So it is not just one in one location, but it was obviously made really crystal clear with our Tatlin show that that time in Kyiv, between 1925 and 1930, was when the Kyiv Art Institute really kind of created, like a little mini Bauhaus. Tatlin came, and Malevich and others, and it really became a unique period to highlight. I think that was both the zenith and the end of the avant-garde, both in Ukraine and anywhere else in the East. Obviously, history is now available to younger contemporary artists, and I think that they take pride in what existed there. I think, even if a lot of them do not fully understand the history and how important and grandiose what these artists were doing was, it definitely exists there. And so obviously it has had an impact, like all history does. I believe it is embedded in every contemporary artist’s work, almost a conceptual to post-conceptual kind of lineage, where a lot of the artists are deconstructing a lot of ideas and work processes from the early 20th century. So it is all there, some champion and highlight it more than others. I think a lot more fashion designers use it aesthetically than visual artists. But it is there. I mean, the history is now available since 1991 in a very big way. I think that one cannot really cut the ties historically. And actually, if anything, it should be talked about and discussed more. So that way, artists realistically can cut the ties in the future if they want to.

VR:

Absolutely. And I think that the reason I was asking this is because I would like to make a statement that Ukrainian art was there before 1991, unlike the beliefs of many people, even the curators of some museums. And that it has a durability – tyaglist (Ukrainian: something that lasts in time, remaining unchanged) in Ukrainian. I love this word, and I cannot translate it in any other language, but I understand this is something that Ukrainians just have within themselves, even unwillingly. And whoever is capable of visualizing it, does it. So, can you think of any examples of something that maybe you have seen recently, or you have seen during your work in Ukraine, that strikes you as a heritage of the Ukrainian avant-garde? I am really curious about that.

PD:

I think of two artists in particular – Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, both of whom work with film and video. I think it is embedded in almost all of their work, the way they install it, the way they deal with film. There is not just avant-garde, but also Ukrainian history, film history, which is in its own right gigantic, and so I think that that is there. To a certain extent, there are many components to Zhanna Kadyrova’s work, that is there. Nikita Kadan, that is there. And these are just some people whom I have worked with. I think once again, it is embedded in every artist from Ukraine, more so than others. It is hard to create distance. I think that distance will only come when there are more discussions about what occurred, which I still do not think there have been enough in Ukraine for people to have other options available.

VR:

I think this return to the avant-garde, and the return to the 20th century, tumultuous history of Ukraine, is a result of the current war and of the attack on the Ukrainian identity, because we are fighting a war for identity, which is on the table. It is not the territories, it is not the sea. It is identity.

You work with the Ukrainian Museum in New York. It is a museum that represents the diaspora: Ukrainians who are not in Ukraine, though, and for me, the diaspora has always been a very interesting phenomenon. It is kind of like this little jewelry box that contains very pure and uncontested cultural markers. You know that sometimes in Ukraine, we lose them simply because it is a more dynamic cultural environment than the diaspora. And how is it working with the diaspora? How do you connect Ukrainians who are in Ukraine with Ukrainians who are not in Ukraine?

PD:

Well, first of all, the diaspora exists because of different immigrations, it started basically at the end of the late 19th century, early 20th century, then after World War Two, then those of Jewish heritage during the 70s, 80s and 90s, and then obviously with the independence since 1991, and I think that, once again, the war has been pivotal. Because there are 63,000 Ukrainians now living in the New York metro area, from Boston down to Washington, to Philadelphia. That is a lot of people, and those numbers are not precise. I don’t have government information, but let’s just say it is a lot of people, and so that has changed the dynamics of what it means to be Ukrainian or Ukrainian diaspora. I think number one is because of the nature of that history. Is that, up until the mid-90s, after the independence of Ukraine, the diaspora, for various reasons, had to live in a bubble. There was no information, and there was no flow. It was a bubble. Everything happened within that bubble. Then, slowly after independence, there was more of a kind a shift of information coming in and out. And I think what has happened is that the war has accelerated it to high speed, and now, with all of these people living here, everything has changed. That whole aspect of diaspora now applies to these new immigrants from one year ago, two years ago, three years ago, so it is also blurred what that word means. There is a bill in the Verkhovna Rada ready for the President to sign, for people to become Ukrainian citizens, if they have grandparents or parents from Ukraine, and people can apply for citizenship. That will be huge because that means that the diaspora will become Ukrainians, and then the whole concept of the diaspora will slowly fade away. And I’m not a sociologist. This is not my wheelhouse, but basically what I see is that you are going to have Ukrainians all over the world, and it will be no different than having British all over the world or French living all over the world, and it will not be this special kind of situation called diaspora. I mean the word will exist, and the context and labeling will still be there, but I think the whole aspect of identity will change drastically, and it is changing right now, because we have a lot of people who cannot wait to move back to Ukraine. But also, we have a lot of people who are not necessarily from Ukraine wanting to move to Ukraine for different reasons. So it has become messy, but in a good way.

VR:

What do you think about the identity of the diaspora? From your point of view, as the curator of the Ukrainian museum, what are the shifts in the cultural identity? Most of all, what have you seen? What changes? What does the war bring to Ukrainians overseas?

PD:

I think it is three very specific things. Some people see themselves here in the United States as citizens of the United States. And they see themselves as having Ukrainian heritage. Great. I think, though, there are those who see themselves, both more strongly from Ukrainian heritage, very proud of their roots, or being Ukrainian but also as Americans. And then you see many who feel that they are just Ukrainians, and they could be from America, but they see themselves on the far extreme, and that percentage is much smaller than the first two, but they see themselves as Ukrainians, very proudly. You know, supporting, doing, actively involved. Some even have homes in Ukraine, a second home where they go sometimes.

VR:

How do you think the museum activity can help forge this identity or help move it forward? Or make it evolve into the new things, because it is definitely going to evolve, like you said, now it is no longer a bubble like it was before, it has been enriched with newcomers. And what do you think the Ukrainian museum can give to this Ukrainian community in terms of identity and in terms of cultural belonging, maybe?

PD:

That is super, super complex, but I’ll try to break it down from my perspective. Where do I start? I think about the museum. It was formed by a group of people who were extremely proud of their heritage and wanted to show off in their immigration to the United States the things that they brought with them, which were not much. So maybe there were some vishyvanka, some craft items out of wood or ceramics, small paintings. So they started a museum to support these kinds of National Folk Art items. And so that is, I think, the core, and then also to, once again, celebrate Ukrainian culture. Those artists who were living here, who immigrated, their number was kind of limited. Fast forward, those people are now in their 80s, maybe late 70s, mostly in their 80s. And it is now their children who are in their 60s and 50s, and their grandchildren who are in their 30s and 20s. And how do you bring everybody together? Because their children, I mean, maybe they grew up seeing these, these national items being made, celebrated, being proud of their heritage, and their grandchildren, who are much more absorbed in American culture and want to run away from what their parents or grandparents were celebrating. Because they just remember being dragged after church, to the museum, to other events. And sure, it was great for that one day, but they do not want to relive that experience. And so, I think it is those three categories, and then the new people who have been moving here over the last ten to twenty years, and the new wave when the war started. So there are really like four audiences that I see, and how do you identify and connect with everybody? Because when we did Maria Prymachenko’s show two years ago, the only people who really knew about her work were those who had come from Ukraine in the last 20 years. Those who have been here for quite a long time, nobody knew the work at all, and it was a learning experience, but it was an important learning experience for everybody. What I am trying to say is, with these kind of exhibits that we are doing, it is also about opening everybody’s eyes, to what has existed in Ukraine, and also, not just in Halychyna, which is where a majority of the immigrants are from, but what is happening in Kyiv and Kharkiv and Odessa, in Dnipro, you know, the whole of Ukraine, because for a lot of people living here in America, Odessa or Kharkiv or Dnipro, it might as well be on Mars. That is something they did; never visited, even now, even before the war. When they went, they went to Lviv, maybe Kyiv, and that was it. There is a lot to cover and a lot to also identify with, because once again, we are in New York. Our audience now is shifting and becoming bigger with the neighborhood, with the city. And this I know, because we have data: 8% of our visitors are Asian, another 10% are Latino, and that could be Dominican, Mexican, Caribbean, you know, Puerto Rican. That is 18% of our current visitorship, our newest members. I would say it is creeping up, too, slowly. Also, about 10-15% have little to no heritage from Ukraine. So there is a bigger shift about people wanting to celebrate our culture on their own terms, through their own eyes and through their own filters, because they like what they see. They want to be part of a learning experience or something in the community, in our neighborhood, and that is great, but it is, once again, a fifth audience that exists. So how do we sustain a balance for everybody? It is not that easy, because, for example, most of the Jewish museums have two audiences: Jewish and non-Jewish. We are tackling a generational shift, new audiences from Ukraine, and also the non-Ukrainian audiences. But I mean, we have to make it work, and it is working. It just makes it more challenging, and we just have to be more sensitive to what we do, and to constantly challenge ourselves, to not be afraid, but to make the kind of leaps that are necessary. And if something fails, it is okay, it is okay. We are not bankers, and we are not doing medical surgery. So it is really about challenging ourselves, but once again, trying to create a balance.

VR:

What do you see as a risky project for the Ukrainian Museum?

PD:

You know, I don’t think anything, to be quite honest, is risky in a real way. We have expanded what we do to contemporary practice. The museum never did much with contemporary. But I think that we have broken barriers in the last three years. They are all mental ones. Barriers like showing contemporary art, showing historical art, expanding what the word Ukrainian means, the whole aspect of media, and that could be photography, video, things like that. We have already done all of that. We have pushed into doing more with performance art, with creating alliances. And I think we just have to be persistent. There is no risk. The only risk that we are going for is, well, actually, it is not a risk. It is a mission to break down and decolonize what it means to be Ukrainian, and take the whole aspect of the word Russian and throw it in the rubbish.

VR:

Yeah, I totally agree with that. Actually, when I talked to Oksana Semenik, she told me a little something about the next project that you are working on. Can you please tell me something about it?

PD:

We are working on a future exhibit of Malevich, and I have already had two visits to Ukraine. I have reached out to various people who have worked with the theme of Malevich, especially Tetiana Filevska, Dmytro Gorbachev. I mean, we need to do this correctly, and so I have invited Tetiana to be a co-curator in that exhibition. And what this led me to in my readings and writings of Malevich, because he was quite a prolific writer, is this whole aspect of influence that does not exist in any book, any catalog on Malevich, is how folk art was the starting point for him, and how he even wrote: “I remember when my mother and my aunts started drawing or painting flowers in our house and birds and squirrels.” So basically, for him, that was the first abstract painting, and a major influence. The Ukrainian folk art, and the kind of influence it had on the 20th century, not just on the avant-garde, but even later, on Iakiv Hnyzdovsky, already here in America, on Sergiy Parajanov and his films. So the exhibition will start in the late 19th century. Yes, covering the avant-garde, but even kind of see its way into the late 50s, and yes, it will be under this heavy political rubric of communism, especially with Parajanov and others. But still, I think it is important that the influence is there, and has always been there. It kind of dissipated realistically already in the 60s and 70s, but still talked about in its influential days. So for us, it is really using the museum’s collection key loans here in America, and also museums that we are borrowing works from in Kyiv to expand upon that, to broaden the history. Because every time I have been to Ukraine, it started when I was working in Ukraine in the late 2000s. Everybody said, “I know about it, but where are the catalogs? Where are the scholarly papers?” They are somewhere. No, they are not. And then somebody told me: “Oh, there was an exhibit in 1967,” and I’m like, “Oh, my God.” And I thought nobody had access to go to Kyiv during that time. And I am sure very few citizens of Kyiv took part in that. You know, there was a brochure that just nobody has anymore, and so there is this kind of forgotten history that we want to invest in, with a lot of our time, in the research, in the publication. I think the exhibition will be great. I think it will be wonderful. But ultimately, it is the catalog that will live on for many years afterward that we need to finish. And that is the focus of the exhibit.

VR:

Since you have such an impressive experience with institutions, what do you think is the biggest thing that the institution can do to help decolonize a culture?

PD:

I think it can only do part of the work that needs to be done. That is just my personal experience. It can only go up to a certain point. It has an immediate impact. All institutions are solid, so they work off of that foundation to make impacts. But yet, to be quite honest with you, as we have seen most recently, for example, the Ilya Repin painting at the Metropolitan Museum, labeled Russian. Well, I wrote to them. I know the director, not well, but we know each other professionally. I wrote to him, and did not even get a response. Talked to him in person at a dinner. And then you have somebody like Oksana Semenik, via social media, create pressure, and they change it. So I think they changed it, not just because of Oksana, but because other people in the community were writing them, because I made an effort. I think it takes a village to set things straight, but an institution can only do so much. Of course, an institution carries a lot of weight, but then so does a group of people, a community, and the community does not necessarily have to be involved with the institution, be it a museum or university, whatever that institution is. We’re moving forward at the Ukrainian Museum, because we ultimately will become a mirror to what is happening in Ukraine. That is the goal; that is ultimately what we need to be. And going back to that word diaspora, diaspora Museum, no, we’re a Ukrainian Museum, and we have to embrace everything Ukrainian; if it is good or bad, we have to show it along with a lot of things that celebrate our history. And that could be from the stone Baba from Eastern Ukraine, to really various antiquities. The museum has to be, what I like to say, a Chinese buffet where you can pick and choose what you like. Maybe try something that you do not know. And I think that is ultimately what our success story will be: to create options for people and never to be just one thing. Because I think that is a failure of a lot of institutions when they start doing the same thing over and over again, because they have some early success. For the Ukrainian Museum, because it is in our history, we should always challenge ourselves and not be afraid of failure, but to show as much Ukrainian culture as possible will be the key to our success.

VR:

This is a very powerful statement, actually, and I thank you for that. In fact, the reason why I was asking is because I spent a semester researching the Ukrainian community in Paris in the beginning of the 20th century, and it was a rather traumatic experience for me, because Centre Pompidou, for example, that owns the biggest modernist collection in Europe, actually has a lot of the so-called Russian avant-garde that the curator does not recognize. He does not realize that he has a lot of Ukrainian art in their collection. When he was asked about Ukrainian art at the beginning of the war, he said, “Yes, we are going to support Ukraine.” And then he went and he gathered some artworks from Zhanna Kadyrova, from Nikita Kadan, and others. He said they were going to show Ukrainian art, but only from the beginning of the 90s. This way, he was stating that Ukraine only started existing in 1991 without acknowledging that Centre Pompidou already owns so much of Ukrainian art. They have Sonia Delaunay, Exter, and Malevich; his “Running Man” is there. It is so complicated for me to deal with. And nobody wants to talk about this in Europe. I think that the institutions are not only a display, but also a research facility. They can have a huge impact, a much bigger one than they think they do. There’s so much research that has already been done by people like me, like Oksana Semenik, like Tetiana Filevska. And we are just here waiting for someone to take our work and use it in museum practice. But it is extremely complicated to reach out.

PD:

Well, that is why we have the exhibition program that we have, and we are also going to be doing an exhibition next year called “Creative Pale” about the Pale settlement. All the Jewish artists from Ukraine who were born and worked in Ukraine have never had an exhibit about it. All of their ancestors live here in New York or in Europe. So we’re going to do the first exhibit of the famous Jewish Ukrainian artists of the 20th century. And then, once again, Repin, we are going to do the first exhibit. And this came about when I, on my own, went to Helsinki before I went to Ukraine last summer, and I went to the museum there. And I said, “Oh, you had a Repin show a year and a half ago.” I met with the director, the curator; everybody was nice. And I said, “Can I have a catalog?” And they were like, “Oh, no, they are sold out.” I said, “No, it could be an old catalog.” “No, no, we do not have any.” And then they said, Look in the bookstores. So I went to all the bookstores in Helsinki, like nine, and nobody had the book. And then I came to Kyiv, and Tetiana Filevska told me that when they did a Repin show, they labelled him Russian, and in the catalog, they did not have the word “Ukrainian” once. That is why they did not give it to me.

So that shocked me, and that even made me more anxious to do a Repin show here, and we are going to do it for our 50th anniversary next year. It is going to be huge. And now I can go back to the museum in Helsinki and say, “You remember you showed me four or five of the 75 drawings you have. Well, we are going to show all 75 drawings, for the first time.” They have never shown the 75 drawings. And then get other select paintings from Ukraine, the few that are in America. And will it be the best Repin show? No, because all the works are in Russia, but it will be a show just like Tatlin or Exter or even Malevich that we will do in the future, decolonizing them. That will be the virus. So all of these exhibits are about decolonizing and finding their right position and trust me, as a Ukrainian American, I totally understand being from Ukraine and the way they lived in St. Petersburg or Moscow. There were two different cultures, but there were no real borders. And the whole aspect of moving here and there is not like what we have in today’s world, where there are borders and things are much more black and white. I understand their perspective, and I also do not want to colonize who they are in a kind of reverse colonization. But let’s just, you know, call it for what it is, if you’re born, spoke, champion, and on your passport said Ukrainian. That does not make you Russian.

Peter Doroshenko is the director at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City. Doroshenko is known for his trailblazing approach to cultural institutions and amplifying them to become topical and dynamic. For eleven years, before his arrival in New York, Doroshenko was the director at the Dallas Contemporary, Texas, the largest non-collecting contemporary art museum in the United States. He has held director positions at: PinchukArtCentre, Kyiv, Ukraine; BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, United Kingdom; SMAK – Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent, Belgium; inova – Institute of Visual Arts, Milwaukee; and curator posts at both the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; and Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse. Doroshenko has organized over two hundred exhibitions over the past thirty-five years including artists: Candice Breitz, Maurizio Cattelan, Francesco Clemente, Andreas Gursky, Peter Halley, Peter Hujar, Lonnie Holley, Pierre Huyghe, John McCracken, Mariko Mori, Kimsooja, David Salle, Julian Schnabel, Pascal Marthine-Tayou, and Piotr Uklanski. He has worked with Ukrainian artists including: Serhiy Bratkov, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Boris Mikhailov, Maria Prymachenko, Janet Sobel, Volodymyr Tatlin, and Yelena Yemchuk. In 2007, 2009, and 2017, he was the commissioner for the Ukrainian National Pavilions at the Venice Biennale. He has lectured and taught at post-graduate programs including: Core Program, Houston; Le Pavilion/Palais de Tokyo, Paris; de Ateliers, Amsterdam; and the Whitney Independent Study Program, New York. While he was on the board of trustees for the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art, Kyiv, from 1997-1999, he was the chair of the education committee which implemented the first formal learning programs in Kyiv surrounding temporary exhibitions.

Valeria Radkevych is a Ukrainian freelance researcher, writer, and art critic. She holds an MA in Visual Arts from the University of Bologna and Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her work explores the intersections of contemporary art and politics, decolonial practices, and media, with a particular focus on the Ukrainian art scene. Based in Italy, she contributes to Artribune, Il Giornale dell’Arte, and Juliet Magazine. In 2024, she founded A Quiet Catalyst, a platform dedicated to art, social politics, and war.