The Dissolution of the Worker: A History of Making Worker-Oriented Art in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

Wei Wu

On May 23, 1942, amidst the Sino-Japanese War, Mao Zedong gave his famous “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” hereafter the Yan’an Talks. The purpose of the forum was to ensure that literature and art would “follow the correct path of development” to help the Chinese people defeat its immediate enemies, which included both the Japanese troops and the KMT government, in order to achieve national liberation.[1] The Rectification Campaign, launched a few months prior, already helped Mao consolidate his authority over the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and unite party members’ ideological beliefs and political orientations. Now his goal was to establish the party’s cultural policy, which all intellectuals would be required to follow. Insisting that literature and art were “an indispensable part of the entire revolutionary cause,”[2] Mao deemed it a top priority to reform and unify intellectuals who came to Yan’an with different experiences and assumptions, and to provide clear guidelines so that works which were, by his standard, conducive to the revolution could be created.

Mao’s first task when giving the Yan’an Talks was to identify the audience that literary and artistic production should serve. He believed that “this problem has been solved long ago by Marxists, especially by Lenin. As early as 1905, Lenin emphasized that our literature and art should ‘serve millions upon millions of laodong renmin (劳动人民, laboring people).’”[3] While artists could learn from a range of sources, whether native or foreign, traditional or new, “the goal must still be to serve renmin dazhong (人民大众, the mass public).”[4]

After 1949, the masses remained the first and most important audience for cultural production and the foundation of cultural policies. That art must serve the masses under the direction of the party was cited as the criterion for cultural production in all three All-China Congresses of Literary and Arts Workers (CLAW) held respectively in 1949, 1953, and 1960.[5] In 1960, after Mao resigned as head of state to take responsibility for the failed Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), national cultural policies no longer evoke the Yan’an Talks or imitate its political rhetoric as frequently.[6] However, the talk was still periodically cited in official press and its principle, that art should serve the people, was never openly questioned or modified.[7] When Mao returned to power after launching the Socialist Education Movement in 1963 and the Cultural Revolution in 1966, cultural workers were again exhorted to study the Yan’an Talks. It was reprinted twice in People’s Daily in 1966 and 1967, where it was celebrated as “the most complete, thorough, correct Marxist-Leninist literary and art line in the history of the proletarian revolution.”[8] Reviews of art exhibitions held during the Cultural Revolution continued to praise works for educating the masses and serving the people.[9]

While no scholarship on art production in Maoist China could fail to mention the significance of the masses as the most critical audience and Mao’s role in establishing its importance, scholars, whether writing in Chinese or English, rarely mention the fact that in the Yan’an Talks, the “masses” are not a single, homogeneous entity. Rather, Mao divides the category of the masses into a set of hierarchically ordered divisions or factions. Mao not only identified the masses as the primary audience, but he also laid out the relative priority of different class factions:

. . . our literature and art are first for gongren (工人, workers), the class that leads the revolution. Secondly, for the peasants, the most numerous and most steadfast allies in the revolution. Thirdly, for the armed workers and peasants, namely the Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies and the other armed units of the people, who are the main forces of the revolutionary war. Fourthly, for the laboring masses and intellectuals of the urban petty bourgeoisie, both of whom are also our allies in the revolution and capable of long-term co-operation with us.[10]

The hierarchy is counterintuitive especially when we consider its historical context. Why would Mao put workers before peasants in 1942, when he was eager to mobilize the peasant majority in the Communist base areas with effective visual propaganda?[11] In addition, the Yan’an Talks were not the only occasion that Mao specified the worker class as the leaders of the socialist revolution and construction.[12] In 1951, Mao attributed the success of the revolution and national reconstruction to “the consolidation and unification [of China] under the leadership of gongren jieji (工人阶级, the worker class) and the CCP.”[13] In 1953, he reiterated that every member of society, including the masses and the cadres, “must wholeheartedly rely on the worker class.”[14] In 1964, he again argued that “the dictatorship of wuchan jieji (无产阶级, the proletariat, also known as “the class with no property”) is led by the worker class.”[15] Similar glorification also frequently occurred in official newspapers.[16] If before 1949 Mao was still relying on Lenin’s authority and thus followed the latter’s belief in the superiority of workers in a socialist revolution,[17] why was the worker class continuously praised after 1949, when he has already established firm control over the CCP and was committed to adapting Marxist-Leninist principles to the Chinese context, which included a large peasant class? What did Mao see in the worker class that justified their prioritization in China, and did his view change over time?

Art offers a unique entry point to answering the question. The CCP recognized visual art as an important propaganda tool that could convey party messages and raise morale more directly than texts.[18] Thus, after the CCP took control of major cities where workers were the majority of the population, it devoted considerable resources and effort to developing gongren meishu (工人美术, workers’ art), which includes artworks made both for and by workers. Due to this persistent top-down approach, workers’ art grew to reflect Mao and the party’s conceptualization of the worker class more than workers’ own concept of their art. By tracing the development of workers’ art, this paper investigates how the CCP’s understanding of the worker class’s political identity and responsibility changed over time in Maoist China (1949-1976).

In May 1949, People’s Daily exhorted cultural workers to “portray labor heroes and exemplary producers more, reflect various economic policies, focus on production themes, become the closest friends with workers, learn production knowledge from them, assist and mobilize workers to write, perform, sing, and paint, to inspire their highest enthusiasm for production.”[19] The sentence identifies two main strategies to serve a worker audience: professional artists should approach workers to make art for them, and workers should be taught by artists how to make art themselves, in other words to become amateur artists. Both methods were carried forward throughout Maoist China, and changes in their implementation and achievement reflect changes in the social, political, and cultural definition of workers during this period. If the worker class in the 1950s and early 60s primarily refers to those who worked in urban industrial factories, the emergence of new subjects in workers’ art in 1966 indicates that the class was gradually expanded to include any laborer, urban or rural, who could organize their work and life in conformity with the latest party principles. At the same time, workers’ art gradually lost its formal uniqueness as workers were required to embrace a new revolutionary aesthetics defined by the Party. Both phenomena show that by the late 1970s, the concept of the “worker” lost its specificity and revealed the reality that, despite his materialist philosophy, Mao defined class by on the basis of ideological attitude.

Turning Artists into Workers

Mao’s recognition of the worker class and its consistent valorization as the leader of all people by official CCP media made it an ideal subject for artists who were now expected to make work for the masses. However, a problem arose. Mao Zedong subscribed to a materialist worldview accordingly to which people’s thoughts and perspectives are conditioned by their material, political, and cultural life.[20] Artists who enjoyed a privileged upbringing and rarely participated in manual labor could not be expected to portray workers in a way that could engage the latter. In particular, artists who stayed in Kuomintang-controlled cities before 1949 during the Sino-Japanese War and the subsequent civil war did not go through the same political training as their comrades in Yan’an. In Mao’s opinion, they were still defined by their experience in the old society which was “semi-feudal, semi-colonial, under the rule of the big landlords and big bourgeoisie.”[21] Thus, before these artists could serve the people, they must first obtain the correct consciousness, lest their bourgeois sentiment contaminate the masses. As Mao dictated in the Yan’an Talks, “without such remolding, they [the intelligentsia] can do nothing well and will be misfits.”[22]

What is the correct consciousness and how could it be learned? In the Yan’an Talks, Mao specified that the proper perspective was the perspective of the proletarian.[23] Though a loan word from Marxism, in the Chinese context, the proletarian status was not based on the shared experience of capitalist oppression which led to a unified insurgent force as defined by Marx. After all, the CCP’s legitimacy to rule relied on the claim that it liberated Chinese people from all forms of oppression. In China’s post-revolutionary context, proletarian consciousness must find another basis. Hence, Mao gave the term a twist: by equating insurgence against capitalism with the pursuit of communism,[24] he defined proletarian consciousness as a political attitude, which refers to the willingness and ability to lead the Communist cause and sacrifice for the people.[25]

In 1949, no one could claim to perpetuate this ideal better than Mao, known for freeing Chinese people from the imperialist Japanese and the corrupted Nationalists and founding a new China based on Communist ideals. This achievement allowed Mao and the CCP under his leadership to appoint themselves as the representatives of the proletariat and the arbiters of revolutionary truth, who then had the authority to define the material and spiritual needs of the people. Since those with the correct consciousness must serve the masses, yet the needs of the masses and the means by which they will be fulfilled came to be stipulated by Mao and the Party, loyalty to the party becomes a crucial component. In this manner “serving the masses” easily enough devolved into “serving the party”. This loyalty could take many forms, and performing labor for party state certainly counts as one of them. After the founding of the PRC, most industries gradually become state-owned and monitored by the CCP.[26] Everyone who worked in these industries generated value for national construction under the CCP’s guidance and thus obtained the correct consciousness.[27] This includes all members of the non-propertied class, farmers and workers alike, who must work for their survival.

However, Mao’s constant celebration of the worker class as the leading class indicates that he saw the consciousness of workers as superior to that of farmers.[28] One of the reasons why workers would have heightened political correctness might be the significance of their labor to China at the time. As Chris Bramall has argued, though Mao frequently stressed the need to engage the peasant population, the largest group numerically in China and the foundation of the nation,[29] his development strategy, which extracted resources from agriculture to generate funds and real resources for industrial growth, clearly prioritized industrial production.[30] As Mao tied the level of political consciousness to the quantity and quality of productive activities one carried out for the nation, urban workers who engaged in the most critical sector naturally enjoy superior political consciousness. While Mao himself never wrote any treatise directly laying out his specific reasons for favoring the worker class, in 1957, he reasoned that a worker could receive a much higher wage than a peasant not only because city life incurred more expenses but also because they generated more value for the nation.[31] In addition, according to a 1959 article published in Meishu (美术, Art), the official journal for the Chinese Artists Association (CAA), an organ of the Propaganda Department of the CCP, workers had heightened political awareness because their interest aligned with the national goal of developing the industrial sector.[32]

As the arbiter of the ideal political consciousness, Mao could also prescribe the way in which someone from a relatively privileged class could ventriloquize the consciousness of the working class. In the Yan’an Talks, he urged all cultural workers to “go among the masses” by using his own experience as an example: he contended that it was only after living and working among the masses that he was able to transcend his bourgeois feelings and change his class position to embrace workers and peasants.[33] This approach was consistent with his materialist worldview, according to which experiencing the material specificity of the worker class should allow artists to obtain the their privileged consciousness and then make works from workers’ perspective. Curiously, according to Jonathan Spence, by 1921, Mao was still a teacher who “knew little about the proletariat, though he had spoken vaguely about doing some industrial work in a ship building yard or factory.”[34] It was likely his leading role in organizing and coordinating major worker strikes in Hunan in 1922 that gave him the experience of “living and working among the masses” and a proletarian consciousness, but we were unsure whether he engaged in any industrial labor at the time.[35] Thus, his own proletarian consciousness was achieved by following a Marxist approach, which associated class consciousness with a shared experience of being exploited and resisting that exploitation. However, this standard, as already mentioned, did not suit the New China where there should not be any exploitation under and thus no resistance against the leadership of Mao and the CCP. Mao had to find another material base for workers’ proletarian consciousness that the to-be-reformed could partake in, and he turned to their critical labor. Now, instead of helping workers organize strikes, intellectuals would acquire the desired consciousness by working in the same physical environment and conducting the same manual labor like workers.

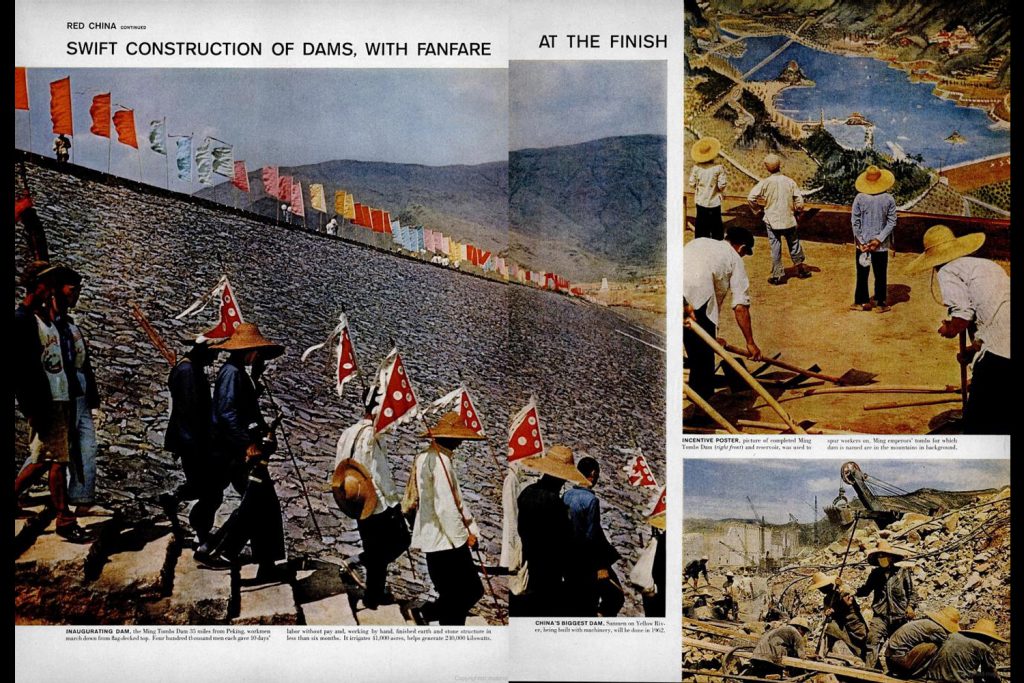

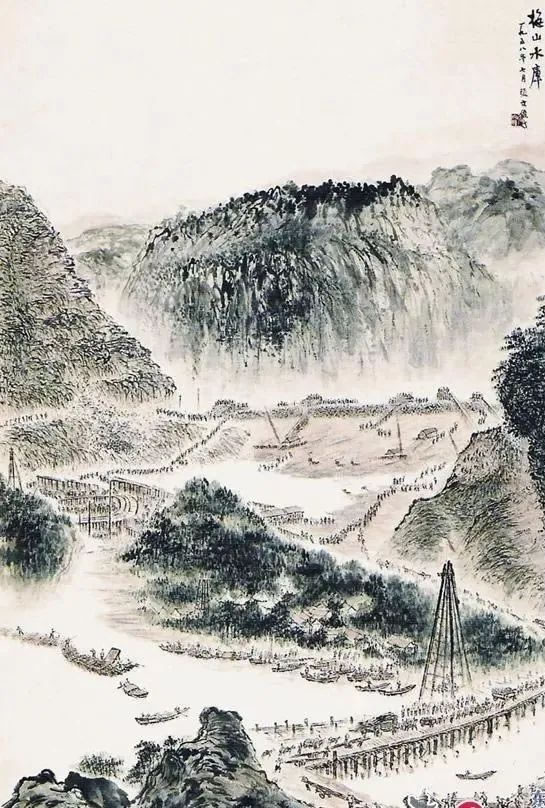

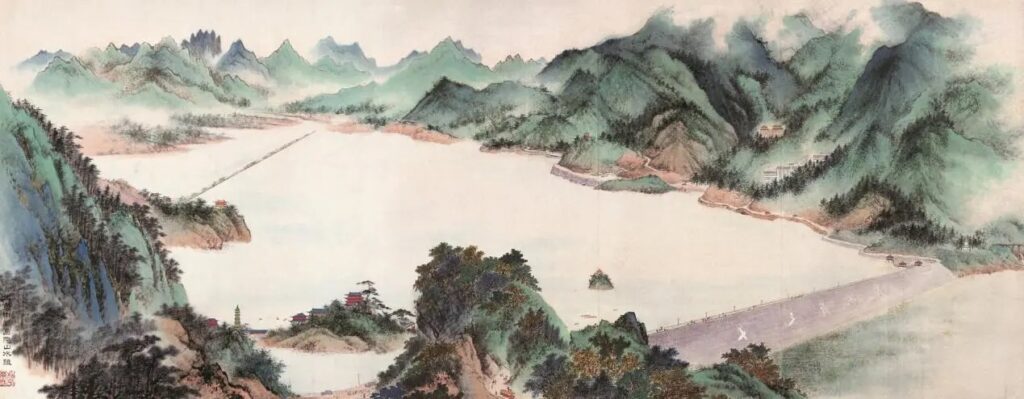

Artists duly understood that their goal was not to learn any practical skills but to emulate workers’ consciousness which derived from their labor. From 1949 to 1969, many artists and cultural cadres wrote about the positive qualities they learned from workers, including their “ability to impartially discern the progressive and the backward in life,”[36] “selfless passion for propaganda,”[37] “adherence to order and leadership,”[38] and “devotion to the party and revolution.”[39] As workers prove their consciousness by contributing to industrial production, reformed artists would advance the same goal by making artworks that reflect upon workers’ material experience, celebrate their achievements, and mobilize them for more production. In other words, they would paint workers for workers. The Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA)’s excursion to the Shisanling Reservoir (also known as the Ming Tomb Reservoir) in 1958 was one of the most worker-oriented of its kind, judging from the paintings and drawings produced as a result of this visit. On May 18, about two hundred students and staff from CAFA arrived at the Shisanling Reservoir, and more professors arrived two days later.[40] Most of them helped construction workers during the day and painted at night.[41] Unlike their predecessors who chose to finish their works after they left the site, CAFA artists immediately began publishing their images on the reservoir newspaper issued for on-site workers and cadres.[42] In addition, upon the suggestion of the general headquarter, when the site was still under construction, CAFA professors Zhou Lingge, Li Keran, Zong Qixiang, Ai Zhongxin, and Dong Xiwen collaborated on a panoramic sketch map of the finished reservoir [Fig.1]. A photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson, sent by Life magazine to document China’s Great Leap Forward, shows workers in front of the completed mural. From the reproduced photograph, the mural is so realistic that the workers seemed to be looking at an actual scene. By showing the grandeur their labor would culminate in and making this future accessible, quite literally, at their fingertips, the mural intends to inspire workers’ confidence and enthusiasm for socialist construction. Its impact is reflected in the shoveling workers, as if they could not restrain their passion and decided to start working right away. The painting’s intention and effect make it an ideal example of art for workers by party standard.

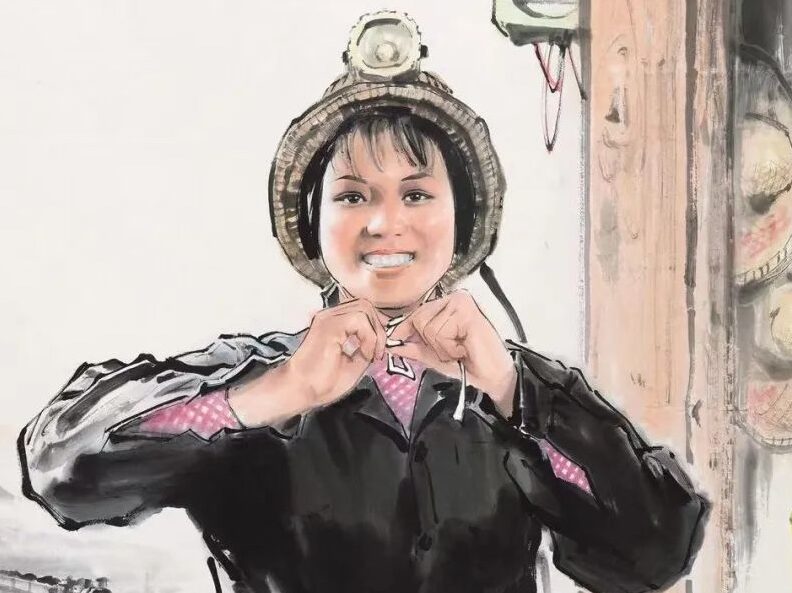

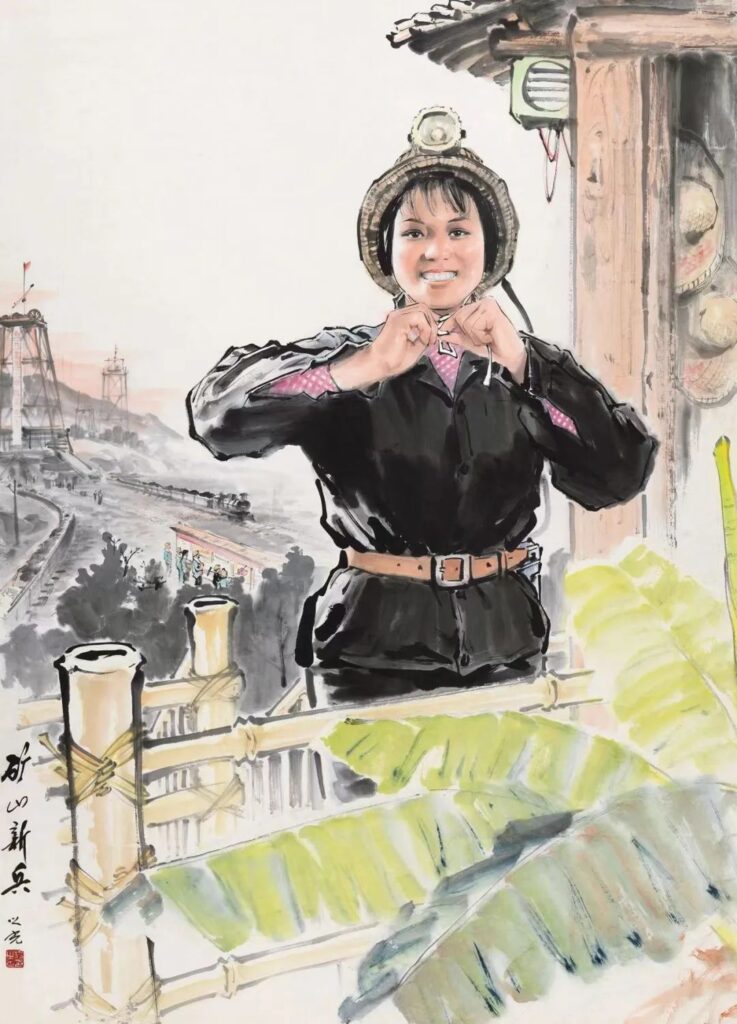

After 1960, the edict for intellectuals to join and follow the masses was briefly relaxed when Liu Shaoqi and his followers modified Mao’s mass-line policy which led to the failure of the Great Leap Forward for a more market-oriented, professionalized approach.[43] However, once Mao expelled Liu and reclaimed power after 1966, artists were again sent to work among workers. While artists in the 1950s mostly chose to commemorate the CCP’s ability to mobilize and organize large-scale collective labor with panoramic compositions, during the Cultural Revolution they made more portraits of individual workers.[44] The change reflected the new cultural policy formulated by Jiang Qing and her followers which emphasized the need to portray “models”, or individuals or groups who have proved their unquestionable loyalty to the party by their passion and action, for the masses to emulate.[45] As part of the initiative, Yang Zhiguang painted A New Force to the Mine (1972) based on a female worker he met while working at a mine [Fig.2]. In the painting, the newcomer is preparing herself for work, and her cheerful expression demonstrates her eagerness to plunge into industrial production to serve the nation and its people. Set apart from the background railway and foreground architecture, which is rendered in freer, broader brush strokes, the worker’s face and clenching fists, which embody her revolutionary determination, have an almost photographic precision? which emphasizes her material specificity. In addition, the use of backlight gives her upper body an eye-catching luminosity, a strategy often used in theatrical productions to highlight the main character. Yang’s formal decisions make it clear that he intended to elevate her as an inspiring model for other workers. However, the upbeat composition becomes eerie rather than inspiring given the back story. The woman Yang used as his model was a widow who just lost her husband to a mine accident and volunteered to replace him at his post.[46] Her potential sadness or struggle has no place in a painting for a model worker, who must display an unquenchable passion for production, the foundation of proletarian consciousness as defined by the party. Paradoxically, while Yang was sent to the mine to get closer to the workers, he was not allowed to sympathize with the widow’s individual tragedy; rather, he must follow the party ideal, which turned real people into lifeless models.

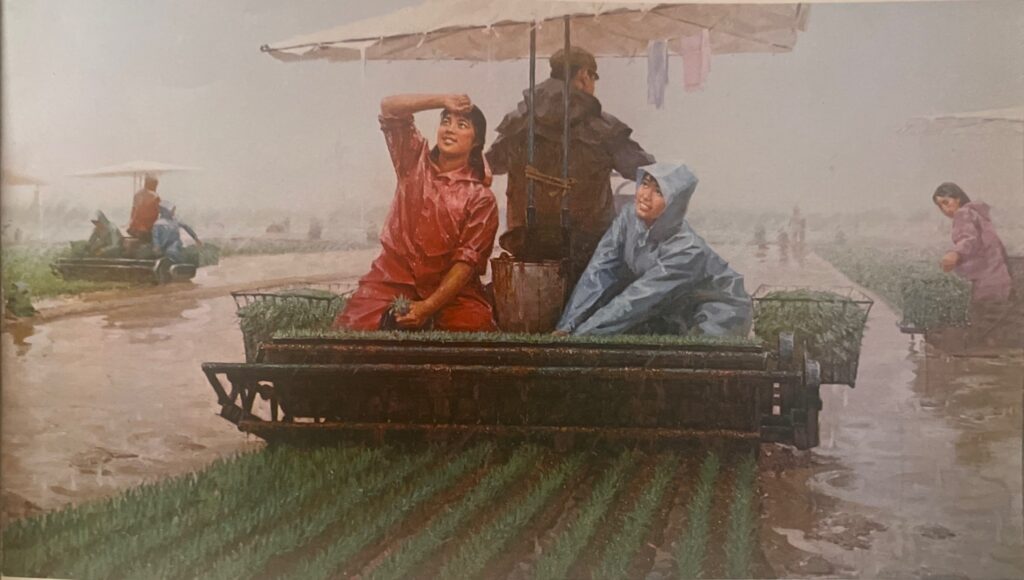

Regrettably, the attempt to transform professional artists through exposure to productive labor was rarely successful. While Mao insisted that all intellectuals must reform themselves by working and living among the masses, he never specified how long they should live with the masses and what exactly they needed to do. In reality, artists’ stays in factories or mines were usually brief. CAFA students and professors spent no more than twelve days at the Shisanling Reservoir.[47] Zhang Wenjun’s stay at Meishan Reservoir in 1954, on the basis of which he painted the widely acclaimed Meishan Reservoir (1958), lasted less than a week [Fig.3].[48] It is questionable whether the limited experience could transform their political consciousness. In addition, not all works produced after these trips target a worker audience. For instance, Meishan Reservoir (1958) was first exhibited by the Jiangsu Provincial Chinese Painting Institute in Beijing in December 1958, while the reservoir was in Anhui province in southeast China.[49] Workers in Meishan did not get a chance to view the painting during its production either: when he visited the reservoir in 1954, Zhang only drew some sketches, and the final composition was finished in Jiangsu after Zhang received suggestions from fellow artists.[50] His first and primary audiences are not the workers he briefly lived and worked with. If Zhang at least included workers in his painting, other artists, for instance members of the Beijing Painting Academy who collaborated on Shisanling Dam (1959) [Fig.4] after working at the Shisanling Reservoir, exhibited landscapes “outwardly unmediated through collective labor.”[51]

This seems to justify Mao’s suspicion that intellectuals, including artists, were “arrogant, conservative, unstable, and undependable,” and that without a forceful method, artists may never become fully reformed proletarians.[52] Those who had completed the required reform might be compromised as soon as they left the factory and returned to the art world, which encouraged them to work on formal issues, technical perfection, and free creativity, an undesirable orientation that might produce “art for art’s sake” and thus be condemned as “bourgeois.”[53] On this basis, artists were subjected to waves of rectification campaigns, where voluntary labor gradually became forced. This created huge disruptions in the art world, rendering many talented artists physically or politically incapable of making art for workers.

Another strategy employed by the CCP to reform the professional art world was to train new artists. After 1949, all bureaucratic institutions, including the art academies, were put under a dual structure in which party functionaries directed the administrators in charge of specific schools and communicated “desirable behavior and the correct ideological response to any given situation.”[54] Young students who received all their education under this highly controlled system, which was designed to moderate their artistic activities and social experience, were expected to develop the desirable proletarian consciousness more easily than those trained before 1949. After their rigorous training in art and politics, they would be hired as instructors in their alma mater or sent to work at other art establishments, gradually replacing previously appointed, politically untrustworthy artists.[55]

In particular, the party center was committed to cultivating students from proletarian backgrounds, whose upbringing by working parents should, presumably, endow them with the correct political consciousness. While proletarian students began entering art academies as early as 1949, they were still the minority as they could not compete in regular college admission with non-proletarian students who often received more guidance from their educated parents.[56] Preferential treatment was introduced in 1958 when the Ministry of Culture required that in five years, all art schools in China should enroll about 60 to 70 percent proletarian students.[57] In response, in that year CAFA suspended its usual admission and only held a worker-peasant-soldier training program, in which 80 percent of the students were worker-peasant-soldier children.[58] The prioritization of proletarian students reached its peak during the Cultural Revolution. When art academies resumed operation in 1972, the first students were admitted solely based on their family backgrounds.[59] In 1976, when the May Seventh College of Arts, established by Jiang Qing on the former CAFA campus, opened for admission, students were required to be children of workers, peasants, or soldiers.[60]

Despite the enormous effort, the strategy of training worker children to be professional artists had a serious drawback. According to Mao’s materialist worldview, if physical labor might transform intellectual artists into proletarians, it is equally likely that an intellectual environment, which appreciated mental labor more than manual labor, might degrade proletarian students into bourgeois artists who prioritized creative freedom over ideological loyalty and might challenge the dominance of Mao and the CCP with their artistic subjectivity. Many artists from worker backgrounds who should be reforming the system with their proletarian consciousness were eventually condemned and purged as rightists. Jiang Feng, a third-generation urban worker who became involved in leftist strike activities as early as 1927, joined the CCP in 1932, and served since 1951 as the vice director of CAFA, was accused of being the “number one rightist in the art world” in 1957.[61] Jin Shangyi, son of a coal miner, graduated as one of twelve students from Konstantin M. Maksimov’s famed postgraduate program in 1957.[62] While his admission to the highly competitive program which must have reviewed every single member’s political background should have proved his political reliability, he was attacked during the Cultural Revolution. If artists with proletarian upbringings were no more resistant to bourgeoise sentiments than their colleagues from more well-to-do families, educating workers to become professional artists only risked their contamination and thus could not effectively cultivate artists for workers. There is, then, something intrinsic to the very experience of mental and creative labor, that is seen as degrading or corrupting a true “proletarian” consciousness.

Training Worker Amateurs

Paralleling the effort to turn politically unreliable artists into proletarian workers, the state also encouraged workers to make art for themselves. Beginning in 1949, worker amateur art was consistently developed under party support. In December 1949, the first worker amateur art exhibition, organized by the Beijing Municipal Committee of Culture, opened to the public. Within a year, almost all factories in major cities had established their own amateur worker art groups.[63] By 1954, most large-scale factories and mines had art groups, some with over a hundred participants.[64]

Why were workers encouraged to make art? In the Marxist tradition, workers can become artists only after a full Communist revolution, during which the full wealth of the economy is, finally, distributed equally. This would mean that workers don’t have to work as hard, and have more free time (for art, leisure, etc.). But this wasn’t the case in China (or in the USSR) since they were still trying to industrialize. As a result they either had to admit that the “revolution” had not been successful (allowing for the universalization of art) or they had to change the political symbolism of art-making. In China, it was initially linked with pressures to maintain their political consciousness and to be more economically productive. People’s Daily reasoned in 1951 that workers could produce great art for their fellow workers despite their limited art education because “they are familiar with workers’ life,”[65] which, as already mentioned, was the materialist foundation for their correct proletarian consciousness. Articles on workers’ art from 1949 to 1974 repeatedly stressed that besides offering pleasure and entertainment, they should inspire workers to “better serve production and construction.”[66] Thus, since 1949, up-lifting celebrations of industrial achievements and critical reflections on problems occurring in the factory became the most prominent subjects in workers’ art. In 1958, Xu Tianmin observed that a worker art exhibition was recognizable for its focus on the factory.[67] In 1965, Song Enhou, an electric welder and art enthusiast at the Wuhan Iron and Steel Corporation, summarized this point in the following manner: “we workers should paint workers.”[68]

The party recognized the educational power of workers’ art and sought to extend its reach. In addition to exhibiting in factories, the best works of worker amateur artists were regularly displayed in public venues such as Cultural Palaces and Halls of Public Education, thereby propagating their superior proletarian consciousness beyond the worker community. In 1951, Cai Ruohong from the Ministry of Culture celebrated the fact that worker’s art had valuable “political effect” among the masses.[69] During the Cultural Revolution, it was also stressed that worker amateurs must work “in close coordination with the party center” to create political education for the people.[70]

If workers’ proletarian consciousness was powerful enough to educate the masses through their artistic production, couldn’t they also help reform the bourgeois professional art world by becoming full-time artists? The party dictated no: workers must remain amateurs. In 1951, the Ministry of Culture stipulated that all mass art activities “must be closely connected to production and cannot violate the principle of being amateur, voluntary, and seasonal.”[71] In 1953, in his report at the second CLAW, Zhou Yang restated the fact that “the purpose of amateur art activities is to raise the cultivation of laborers, not to help amateur artists leave their basic productive activities.”[72] In 1958, professional artists were warned that they should not train workers to be professionals since they must be “amateurs instead of leaving productions.”[73] During the Cultural Revolution, worker amateurs were praised for “not abandoning their labor or the masses” while producing art.[74] Instead of a fear that their absence might disrupt normal industrial production, workers could not leave the production line because they must remain connected to their labor, the material foundation for their privileged consciousness which allowed them to make effective works in the first place. In 1958, Hua Xia pointed out that after workers left the production line, their creations became less moving and powerful.[75]

For the same reason, worker amateurs were trained differently from professional artists. As early as 1951, Cai Ruohong already deemed rigorous training for worker amateurs to be unnecessary as their task was to “express advanced political thought with relatively easy art forms.”[76] Moreover, systematic academic training, which starts with drawing lines, plaster casts, and outdoor landscapes, was said to detach workers from their working environment.[77] This more professional approach incorrectly encouraged workers to focus on artistry and form instead of content, a tendency that reflects a “bourgeoise view of art” that is “the source of all evils.”[78] After a decade of participating in the worker art movement, Hua Xia cautioned that technical studies did not motivate workers to fulfill their political tasks but only instigated them to become full-time artists who could escape manual labor and create works to their own likings.[79] Their observations were further supported by worker amateurs’ self-reflections that technical training did not help them produce effective propaganda.[80]Instead of systematic classes, workers were taught basic techniques immediately applicable to the factory’s need for visual propaganda. Free-hand sketching of workers and productions were deemed more helpful than technical exercises.[81] When CAFA organized its training session for amateur workers in 1958, they primarily taught workers how to make various forms of propaganda. Workers were immediately encouraged to paint, and lessons on drawing and color were carried out according to their creative needs.[82] The same approach continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[83]

The First National Exhibitions of Worker Amateurs

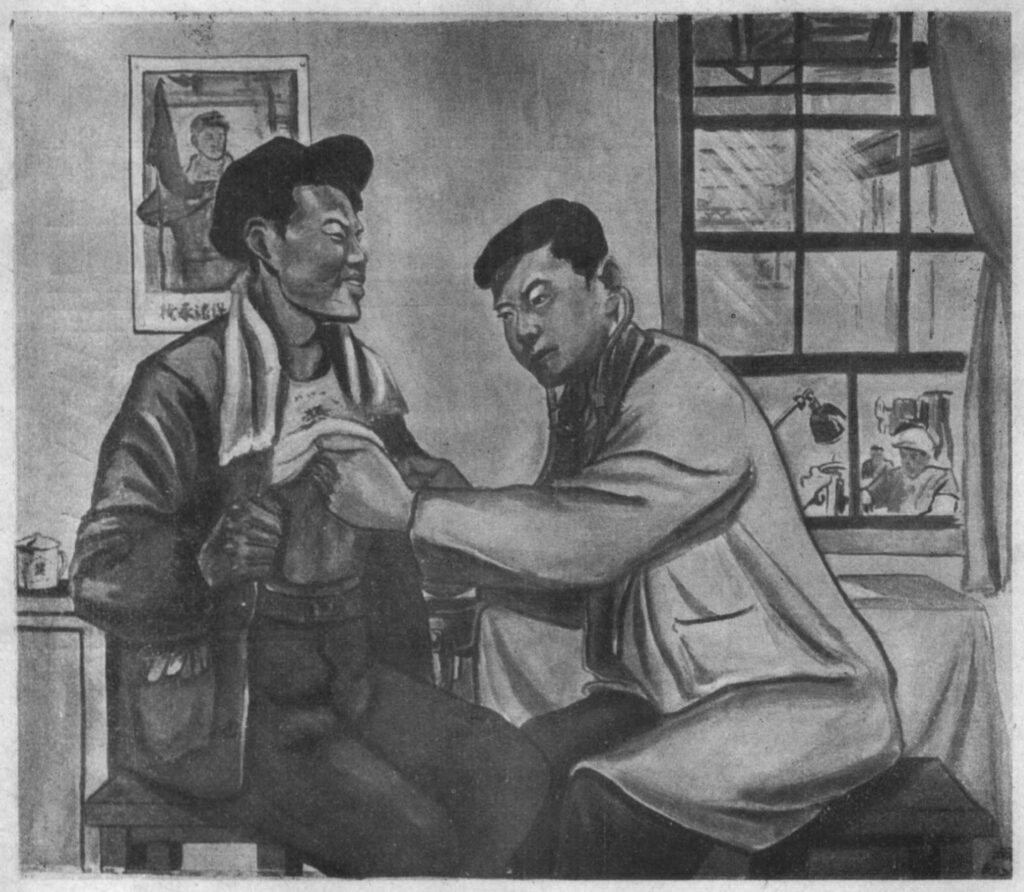

The development of worker amateur art reached a peak in 1955 in the first Worker Amateur Art Exhibition (hereafter the first Exhibition) co-organized by the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and CAA, and featuring more than 300 works. The second Worker Amateur Art Exhibition (hereafter the second Exhibition) in 1960 doubled in scale, featuring more than 600 works.[84] A brief analysis of works in the two exhibitions shows their conformity with party guidelines. Works in both exhibitions focused on workers’ immediate social experience, although they mostly presented an idealized image of their life and avoided its less pleasant aspects, except when criticizing behavior that would compromise group performance and production goals.[85] For instance, when Wang Xuexiang depicted a worker’s visit to the factory doctor in Serve the Production, he did not portray a worrisome patient seeking medical help after an accident, but a jolly worker checking in to make sure his body is at its best condition, which seems to be redundant given his ruddy cheeks and strong physique [Fig. 5]. In the second Exhibition, while workers were encouraged to diversify their content, they remained within these limits and continued to celebrate their loyalty to the party and their commitment to socialist construction.[86] Only a few landscape, still lifes, and decorative patterns were included, perhaps to prove that their creativity was on the same level as professional artists, which was consistent with the party rhetoric during the Great Leap Forward that valued mass intelligence and passion more than professional planning.[87] These works sometimes also have political implications. For instance, at a time when Mao was constantly celebrated as the Red Sun that all Chinese people turned to like sunflowers, viewers would have no trouble in interpretating Chen Sianshui’s Sunflower as a tribute to Mao [Fig. 6].

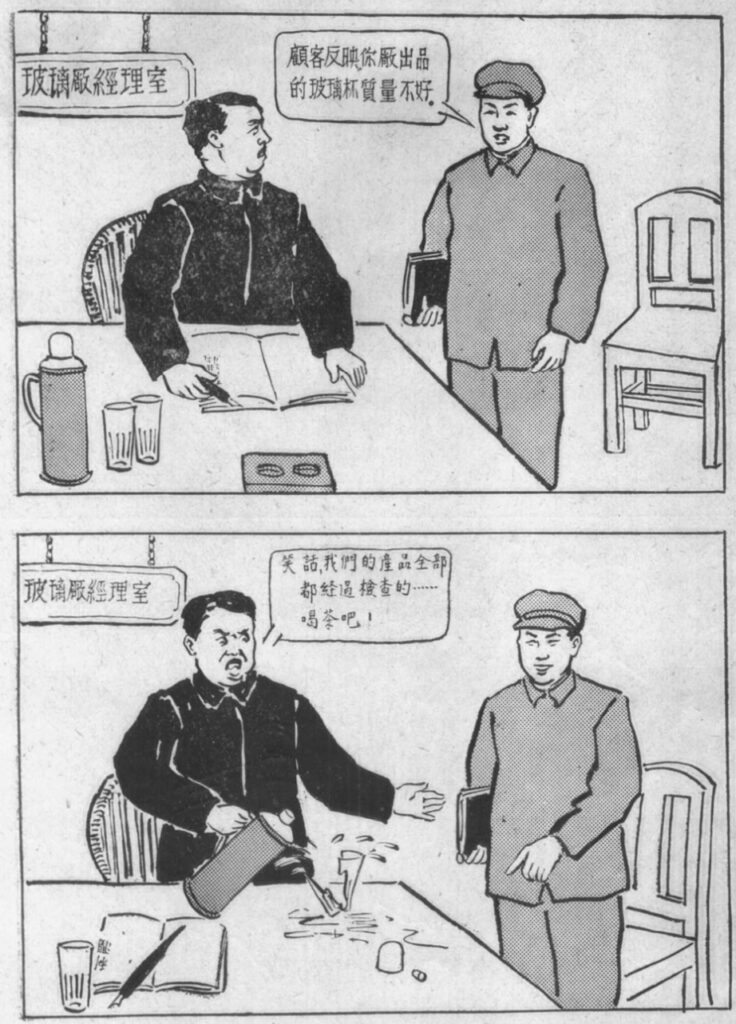

Manhua (漫画, comics) was the favorite genre of worker artists, and constituted more than one-third of the works exhibited in the first Exhibition.[88] Chen Su’s review of the exhibition praised comics as “the most numerous, most representative of worker’s art, and the most popular.”[89] They were no longer the majority in the second Exhibition, as workers also submitted ink paintings, watercolor, oil paintings, woodcut, and sculpture.[90] However, in his review, Hua Junwu continued to commend workers on their high artistic and political achievement in comics.[91] Comics were celebrated as the quintessential worker’s art not only for their lighthearted content and relatively simple style but for their immediacy. More quickly executed than other media, they could reflect on events in a factory in real time and were thus more relatable to their worker audience.[92] For instance, Hu Fuqing’s award-winning Facts Spoke mocks an arrogant manager of a glass factory who disregards criticism of his glass tumblers only to embarrass himself in front of the inspector when his glass breaks as soon as hot water is poured in [Fig.7]. Both the specificity of the story and the colloquial conversation suggest that the comics was based on a true story. The smile on the inspector’s face when he saw the glass breaking lightens up the mood, which encourages viewers to laugh with the inspector and takes in the lesson in a relaxed spirit.

After 1960, state support for amateur art was reduced. Mao’s mass mobilization strategy, which inspired the Great Leap Forward, proved to be a massive failure, and all state policies in 1961 shifted to rely more on trained professionals instead of the masses.[93] In particular, Prime Minister Zhou Enlai called for “the return of amateur artists to their regular jobs.”[94] Workers nation-wide did not stop making art, as reports on worker art activities were published in mainstream journals and newspapers throughout the 1960s.[95] However, there would not be another national worker’s art exhibition until 1974, at the height of the Cultural Revolution, when the Shanghai, Yangquan, Lüda Workers’ Painting Exhibition (hereafter the Three Cities Worker Exhibition) opened in Beijing on October 1.

The Culmination of the Development of Worker Art

The Three Cities Worker Exhibition achieved an unprecedented status. It was celebrated as a yangban, a concept proposed by Jiang Qing during the Cultural Revolution to signify outstanding cultural productions whose content and form most accurately represent the moral beliefs and aesthetics of the party.[96] In addition to being held in the National Art Museum of China, a site previously reserved for professional artists and exhibitions, the Beijing Foreign Language Press published an English catalog for the exhibition titled Graphic Art by Workers in Shanghai, Yangquan and Luta. Before this, workers’ art made in the PRC was never brought to an international audience. The fact that this exhibition was deemed sufficient to represent China proves the significance of worker’s art in the eyes of China’s leadership.

Based on the catalog, the distribution of media in workers’ art productions changed drastically. Comics, which by 1965 were still celebrated as one of worker amateurs’ highest achievements,[97] were nowhere to be found and were rarely mentioned in reviews. Worker did not stop making comics: In 1974, workers in Lüda still produced more than two hundred propaganda posters and comics for the “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” Campaign.[98] Comics were simply no longer considered a medium representative of worker amateur art. Instead, fine arts dominated the exhibition as well as the catalog which includes eight oil paintings, eighteen ink paintings, and thirty-one woodcuts. Medium-wise, the exhibition is no longer distinguishable from a professional art exhibition.

There were political reasons behind this professionalization. Since 1958, instances of workers excelling in media traditionally dominated by professional artists were highlighted against cadres who believed that professional artists deserved preferential treatment, including relaxed ideological control, because only they could create good quality art.[99] In particular, during the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s and later Jiang Qing’s political enemies, including Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, and Lin Biao, were all accused as “capitalist roaders” who looked down upon the creativity of the masses and gave precedence to professionals.[100] Celebrating workers’ artistic achievements was one way of ridiculing their erroneous belief and denouncing these cadres. Exhibited after the “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” Campaign, the Three Cities Worker Exhibition was specifically praised as a “powerful cannon” against Lin Biao.[101]

In addition, art historian Winnie Tsang has argued that around 1969, the party felt the need to replace the spontaneous yet chaotic outlook of Red Guard art, represented by comics and posters, with a more controlled and stable image of national unity embodied in conventional fine art genres with established styles and techniques.[102] However, Jiang Qing and her followers in the Cultural Revolution Small Group also feared that this shift might rehabilitate recently degraded art cadres and artists who once helped form these conventions and could threaten their standing.[103] Celebrating the creativity of worker amateurs installed them as capable alternatives to professional artists and prevented the latter’s return to power.[104]

However, how can worker amateurs, who only received training to produce propaganda posters and were intentionally distanced from professional artists, paint like professionals, especially when the socialist realist style favored by Jiang Qing requires considerable skills? To help amateurs paint professionally, the CCP-led People’s Fine Arts Publishing House produced a series of instruction manuals on how to draw typical workers, peasants, and soldiers for them to copy the figures and compositions.[105] When the quality was still unsatisfactory, art professionals were summoned to help. During the Cultural Revolution, the practice of having professional artists polish and even repaint works made by amateur artists before their formal exhibition to a national audience, which was previously carried out under the name of “collective art production,” was fully institutionalized.[106] Since the National Art Exhibition resumed in 1972, all subsequent national exhibitions, including the Three Cities Worker Exhibition, recruited professional artists into Painting Correction Groups to revise inferior paintings, sometimes without the knowledge of amateur authors.[107] While none of these artists could have their names listed as co-authors, exhibitions with their participation came to be “dominated by a narrowly defined academic style,” as Julia Andrews has pointed out.[108] For instance, Chao Jung-chi’s ink painting, She Visits Every Gallery [Fig.8], is similar to Yang Zhiguang’s Newcomer to the Mine in both subject and style, though technically less accomplished [Fig.2]. The female workers don identical headgear, and their clothes differ only in colors. Both artists set their models’ upper body against a neutral ground, and both contrast realistic portrayals of the worker’s hands and face with freer treatment of her attire and background elements.

A new kind of “art worker” also emerged as an important contributor to workers’ art. 14 out of 71 works reproduced in the 1974 exhibition catalog were identified as made by “art workers” [Fig.9]. They were mostly zhiqing (知青, rusticated youth) middle school or high school graduates sent or volunteered to work in rural villages and factories) who, unlike worker amateurs, received more formal training in Children’s Palace or middle school art classes.[109] At a time when amateur paintings needed to look professional, these semi-professionals were highly valued and some even enjoyed the privilege of being excused from productive labor.[110]

Besides academic professionalism, new nianhua (年画, New Year’s painting) also had a strong presence in the Three Cities Exhibition. Considered a successful reform of the popular yet superstitious old nianhua, new nianhua replaces its prototype’s folk religious content with revolutionary themes, while keeping its festive energy and colorful outlook that appealed to the masses.[111] Since 1942, it was consistently promoted as an art form welcomed by the people, and its popularity was reaffirmed during the Cultural Revolution.[112] The catalog of the Three Cities Exhibition reproduced six new nianhua, [Fig.10],[113] and several ink paintings also show the direct influence of nianhua aesthetics, including their use of unmodulated bright colors [Fig.11]. However, neither old or new nianhua was associated with the worker community. As a folk art form, nianhua was traditionally purchased by rural villagers to celebrate the Chinese New Year.[114] After 1949, despite attempts to engage workers in its production and consumption, its consumers remained primarily rural.[115] In 1975, Li Baoyi continued to point out that “the greatest audience of nianhua is hundreds of millions of peasants.”[116] The relative prominence of this rural aesthetics in a worker’s art exhibition suggests that the term “worker” no longer refers exclusively to those working in urban factories. The diversification in content pointed in the same direction. While the majority of works in the Three Cities exhibition still depicted workers’ productive and political life, six focused on agricultural production and six portrayed militia activities.[117] It seems like the category “worker” could now be applied to any member of the broader working class.

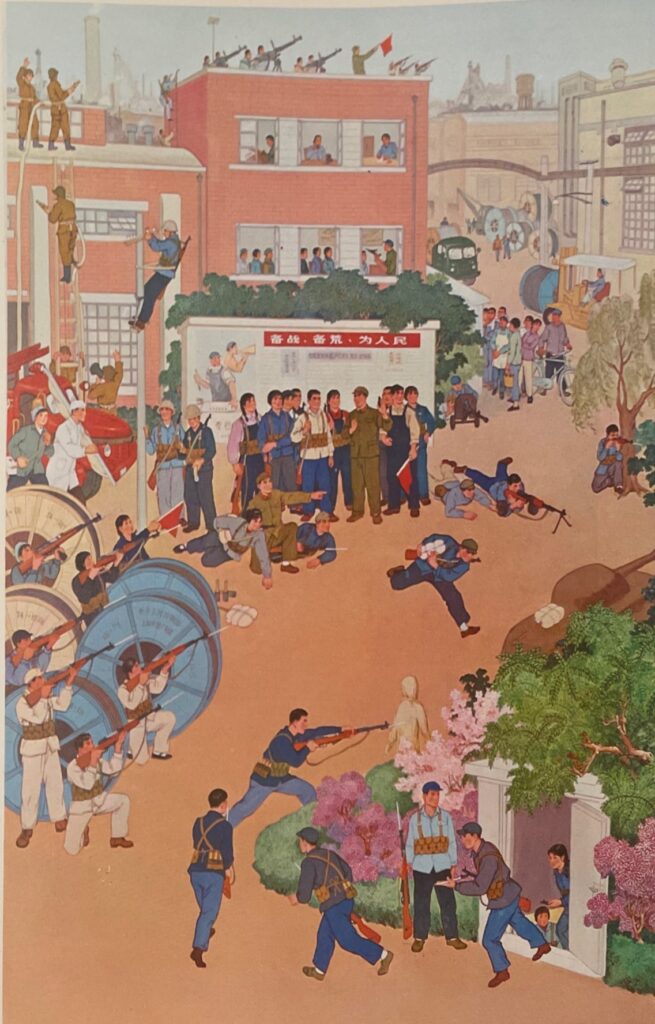

Another prominent aesthetic in the exhibition involves the depiction of theatrical political struggle. These group portraits all have a main character at the center of the composition. Often at the top of a visual pyramid, his pose—one fist clenching, the other hand extending to the crowd—demonstrates his unwavering faith and revolutionary zeal, extending an invitation for fellow workers to follow his example. Criticizing Lin Biao and Confucius with Strong Fighting Will by Zhou Xiaojun, Wang Chunyan, and Shi Dawei, is one of the most creative in this genre in highlighting the main character [Fig.12]. Not only was he standing right under the red banner declaring the name of the political struggle, but those around him either had their backs turned to the viewer or were rendered with pale colors and hazy lines, making him the only figure in focus as well. Both the militant sentiment and the artistic style which emphasized the main hero by making him bigger, taller, and brighter were derived from Jiang Qing’s model operas. Adapted from actual war stories and political struggles, these operas eulogized revolutionary protagonists aligned with Maoist principles by elevating them not only above their class enemies but also above their staunch followers.[118] As Jiang Qing and her followers heralded the model operas as national models for artists in all disciplines, worker amateurs were instructed to conform to creative principles of the model operas instead of their real-life observations, thus shifting the basis of their creation from the real to the ideal.

This militant sentiment not only influenced amateur artists (and their professional collaborators) but is also reflected in the language used by critics to describe workers’ art. Every review of the Three Cities Worker Art Exhibition emphasized “zhandouxing (战斗性, combativeness)” as “the most distinctive feature” of workers’ art.[119] Worker amateurs participating in the exhibition were no longer described as “workers paint[ing] workers,” but as “revolutionaries paint[ing] revolutions.”[120] This change can be attributed to the rise to power of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) during the Cultural Revolution. Since 1964, Mao began to rely heavily on the PLA led by Lin Biao to reclaim his power. As Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals argue, despite the enthusiastic participation of workers and students, it was the support of the PLA that determined the outcome of their rebellions and the entire Cultural Revolution, as the PLA not only helped them with violent take-overs but was also responsible for subduing out-of-control upheavals.[121] When the Anshan Iron and Steel Plant fell into disarray in 1967, the central authorities sent the PLA to control the factory instead of relying on the political consciousness of the workers.[122] When a new Central Committee was elected in April 1969, PLA members occupied thirty-five percent of the seats.[123]

The PLA’s dominance of the cultural sphere began on the eve of the Cultural Revolution. In February 1966, the PLA’s General Political Department held a nineteen-day conference in Shanghai on army literary and art works, in which Jiang Qing instructed the army to study Mao Zedong thought and create proletarian art. Being the first to receive these directions regarding cultural production, which became absolute creative principles during the Cultural Revolution, the army was expected to model them for the entire nation.[124] As Frank Dikötter reasons, at the time Mao held a “fanatical vision… in which every man and every woman became a soldier.”[125] Even after Lin Biao died of a plane crash in 1971 and the PLA no longer took absolute political control, this militant sentiment remained imbedded in the visual and verbal discourse of the Cultural Revolution, which is one of the reasons why the Three Cities Worker Exhibition continued to be described as “combatant” and “revolutionary” and featured paintings of militia activities [Fig.8].[126]

Judging from its greater diversity in content and form, the Three Cities Worker Exhibition marks a momentous development in the worker art movement. Paradoxically, the exhibition was also the least worker-specific. By 1976, “workers’ art” is no longer defined by workers’ materialist experience in urban factories, which was once the basis for their privileged political consciousness. Rather, it might be representing the life and aesthetics of peasants and soldiers with the help of professional artists. Although the worker continued to be extolled as the leader of the Chinese people during the Cultural Revolution,[127] when the term “worker” lost its specificity, the celebration became empty talk that reflected the CCP’s rhetorical habit more than workers’ actual social and political status.

This change should not come as a surprise, however. As mentioned in the first section, Mao defined proletarian consciousness as a commitment to serve the needs of the masses according to his plan. This essentially made accordance with Mao’s interests the most important factor in determining one’s political stance.[128] When his goal was rapid industrial development, workers became national models for their productivity; when his priority was to reclaim power through whatever means possible, soldiers were praised as the most revolutionary and all must emulate their militant spirit. It is no coincidence that one year after he formed his alliance with the PLA in 1963, Mao instructed all levels of industrial departments, from the Ministry of Industry down to every factory and mine, to learn from the PLA to raise workers’ revolutionary spirit.[129] When workers no longer embody the ideal political consciousness, workers’ art, considered a potent educational tool, must assist them in catching up to the latest standard. Thus, in the Three Cities Worker Exhibition, portrayals of the particular experiences and mentality of the worker class made room for representations of the new PLA model.

Conclusion

The Three Cities Worker Exhibition provides, in many ways, a final review of workers’ art which developed over two decades since the founding of the PRC. It demonstrates great variety and progression instead of a homogeneity and stagnation usually ascribed to art produced during the Cultural Revolution. However, this diversity was achieved at the expense of specificity, as the inclusion of folk aesthetics, military sentiments, and revolutionary content blurred the distinctiveness of workers’ art. The fact that such elements could infiltrate workers’ art shows that workers never owned the concept of proletarian consciousness. They were only celebrated as the leading class because Mao and the party deemed their labor critical to their developmental strategy. Once Mao revised his goal and discovered a more effective means of support, they were directed to emulate the new ideal. However, as the worker class had represented the correct proletarian consciousness for so long, instead of being replaced by another category, it integrated characteristics of other social groups and remained a powerful label during the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s 1957 vision, where every member of the society would one day become part of the worker class—the only prospective class—was eventually realized in a distorted manner.[130]

After the Cultural Revolution, the worker class was deprived of its political prestige. Workers were no longer considered the leader of the proletarian class but referred to as “ordinary laborers,” and the new economic polices often put them at a disadvantage.[131] However, as rapid urban development required more workers and drew more people to cities, the worker class expanded and its economic and political significance grew. Recently, efforts have begun again to establish a worker’s culture. For instance, in 2005, Xu Duo, Sun Heng and others founded Gongren Zhijia (工人之家, the Migrant Workers Home) in Picun, Beijing, aimed at improving migrant workers’ social welfare and enriching their cultural lives. Among its many activities, it organized the Workers Art Festival and various art workshops.

Despite changes in the social and political environment, questions and challenges raised decades ago are still relevant to developing worker’s culture in a depoliticized post-socialist China. For instance, who can define a worker class, its perspective, and its needs? Should worker’s class identity be based upon social, political or cultural factors? What is the worker class’s relationship with bourgeois capitalism and socialist imaginations? How can an art be created for this new community, and who should be responsible for creating it? What’s the relationship between workers and intellectuals? I hope this historical review can serve as a starting point for future theoretical consideration and practical experiments.

Wei Wu is Ph.D. Candidate in the History of Art at the University of California, San Diego. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary Chinese art, in particular Republican Chinese visual culture, print culture, and intellectual history. Her dissertation investigates how Republican woodcut artists formed and articulated their understandings of the public and the nation through their works.

Notes

[1] Mao Zedong, “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art (在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话),” first issued May 2, 1949 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-194205.htm

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] For detailed phrasing, refer to talks issued at the All-China Congress of Literary and Arts Workers republished by China Federation of Literary and Art Circle, http://www.cflac.org.cn/wdh/cflac_wdh-1th.html.

[6] Maria Galikowski, Art and Politics in China, 1949-1984 (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1998), 114.

[7] For instance, see “The National Art World Passionately Commemorates the 20th anniversary of the issuance of Comrade Mao’s ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum On Literature and Art (全国美术界热烈纪念毛泽东同志《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》发表20周年),’” Meishu 4 (1962): 4. Meishu also published a special column “Combine with the Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers, Reflect the Spirit of the Time(与工农兵结合,反映时代精神)” in the fifth issue of 1964.

[8] “Chairman Mao’s ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum On Literature and Art’ Talentedly and Creatively Developed Marxist-Leninist Worldview and Literary and Art Policies (毛泽东主席的《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》天才地创造性地发展了马列主义世界观和文艺理论),” People’s Daily (July 5, 1966): 4.

[9] Winnie Tsang, “Creating National Narrative: The Red Guard Art Exhibitions and the National Exhibitions in the Chinese Cultural Revolution 1966-1976,” Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture 3, no. 1 (January 2014): 119.

[10] Mao, “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art.” In the following discussion, I use the term “worker” to refer exclusively to those working in industries.

[11] Julia Andrews, Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1979 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 18.

[12] In his writings in the 1950s and 1960s, Mao has repeatedly differentiated gongrenjieji (the worker class) from wuchanjieji (the proletarian). Unlike the latter, the former excludes peasants and soldiers, and is thus a category used exclusively for workers. For instance, see Mao Zedong, “Be a Thorough Revolutionary(做一个完全的革命派),” first issued June 23, 1950 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19500623.htm; “Speech at the National Congress of the Communist Party of China (在中国共产党全国代表会议上的讲话),” first issued March 21, 1955 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-195503.htm; “Speech at the Ninth Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee (在八届九中全会上的讲话),” first issued January 18, 1961 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/5-002.htm

[13] Mao Zedong, “The Great Victory of the Three Great Movements (三大运动的伟大胜利),” first issued October 23, 1951 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19511023.htm”

[14] Mao Zedong, “Against Bourgeoise Thought in the Party (反对党内的资产阶级思想),” first issued August 12, 1953 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19530812.htm

[15] Mao Zedong, “Historical Lesson on the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (无产阶级专政的历史教训),” first issued July 14, 1964 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/5-098.htm

[16] For instance, in 1952, Liu Heng in People’s Daily stresses that the cultural world must perpetuate “the thought of the worker class as the only guiding principle.” Liu Heng, “East China and Shanghai Cultural World Carries Out the Rectification Campaign, Cultural Cadres Take the Lead to Self-Criticism (华东、上海文艺界开展整风学习运动, 文艺领导干部带头进行检讨),” People’s Daily (June 27, 1952): 3. In 1957, People’s Daily reemphasizes that “our nation is a socialist country led by the worker class.” See “Remain Hands-off: Perpetuate the Policy to ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom and a Hundred Schools of Thought Content’ (继续放手,贯彻“百花齐放、百家争鸣”的方针),” People’s Daily (1957.4.10): 1. In 1974, another article states that “the worker class is the greatest class in human history…[and] the master of our great sociality era.” See Huang Pimo, Wang Wusheng, and Zhou Bingchen, “Foster the Spirit of the Worker Class, Convey the Passion for Revolutionary Fight: Joyfully Watch ‘The Shanghai, Yangquan, Lüda Workers’ Painting Exhibition’ (长工人阶级志气,抒革命战斗豪情:喜看《上海、阳泉、旅大工人画展》),” People’s Daily (1974.10.30): 2.

[17] Xing Lu, The Rhetoric of Mao Zedong: Transforming China and Its People (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2017), 109-110

[18] Galikowski, 10.

[19] Li Bozhao, “Beginning from ‘the Red Flag Song’ (从“红旗歌”说起),” People’s Daily (May 8, 1949): 4.

[20] Lu, 43.

[21] Mao, “Talks at the Yan’an Forum On Literature and Art.”

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Mao, “On People’s Democratic Dictatorship (论人民民主专政),” first issued June 30, 1949 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: https://www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19490630.htm

[25] Lu, 99.

[26] Chris Bramall, Chinese Economic Development (London: Routledge, 2009), 89.

[27] Mao’s proclamation that workers “always had high political consciousness and labor enthusiasm” suggests the connection he forged between the two attributes. See Mao Zedong, “On Ten Major Relationships (论十大关系), ” first issued April 25, 1956 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19560425.htm

[28] Compared to rural peasants, workers received more special treatment in their social and political life. As Carl Riskin has pointed out, since 1951, urban workers not only received more incomes but also had better job security and social insurance compared to rural peasants. See Carl Riskin, China’s Political Economy: The Quest for Development Since 1949 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 62.

[29] For instance, see Mao Zedong, “Speech at the Meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee (在中央政治局会议上的讲话),” first issued June 15, 1953 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/3-036.htm

[30] Bramall, 247.

[31] Mao Zedong, “Speech at the Meeting of Party Committee Secretaries of Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions (在省市自治区党委书记会议上的讲话),” first issued January 1957 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-195701.htm

[32] He Li, “Inspired by a Woman Electric Welder (从女电焊工想起),” Meishu 3 (1960): 27.

[33] Mao, “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art.”

[34] Jonathan D. Spence, Mao Zedong (New York: Viking, 1999), 53.

[35] Ibid., 59.

[36] Tong Heng, “Workers’ Comics (工人的漫画),” People’s Daily (May 19, 1955): 3.

[37] Tang Yun, “To Reform in Labor (要在劳动中改造),” Meishu 1 (1959): 47.

[38] Zhang Wenjun, “Experience Learning the Creation of Chinese Painting (学习中国画创作的体会),” Meishu 1 (1959): 6.

[39] Zhou Sicong, “Spend My Whole Life Learning from Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers (向工农兵学习一辈子),” Meishu 2 (1966): 40.

[40] Qi Su, “Artists and Art Soldiers in the Construction Site of Shisanling Reservoir (美术家和美术兵在十三陵水库工地),” Meishu 6 (1958): 4.

[41] Christine I. Ho, “‘The People Eat for Free’ and the Art of Collective Production in Maoist China,” The Art Bulletin 98, no. 3 (2016): 365. www.jstor.org/stable/43947932

[42] “Going Deep into the Masses, Reform Thoughts, and Popularize Vigorously: Beijing Artists Active at Shisanling Reservoir (深入群众 改造思想 大力普及: 北京美术家活跃在十三陵水库工地),” Meishu 6 (1958): 3.

[43] Riskin, 149.

[44] Lüsheng Chen, The Art History of the People’s Republic of China: 1949-1966 [Xin Zhongguo Meishu Tushi: 1949-1966] (China Youth Publishing Group: 2000), 153.

[45] This creative principle is known as “the three prominences,” which required artists to emphasize the positive in all figures, the heroic in positive figures, and the central figure in heroic figures. See Paul Clark, The Chinese Cultural Revolution: a History (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 46.

[46] Hong Lu, Art during and After the Cultural Revolution: 1966-1978 [文革与后文革美术: 1966-1978] (Taiwan: yishujia chubanshe, 2014): 46.

[47] Qi Su, 4.

[48] Zhang Wenjun, “Experience Learning the Creation of Chinese Painting (学习中国画创作的体会),” Meishu 1 (1959): 6.

[49] Yi Gu, Chinese Ways of Seeing and Open-Air Painting (Harvard University Asia Center, 2020), 176. Similarly, works created by a group of Nanjing artists sent to factories and mine fields in 1958 were first exhibited in Nanjing and then sent to tour in major factories. See “Nanjing Painters Going Deep into Mines and Exhibiting Sketches (南京画家深入工矿并展出速写),” Meishu 6 (1958): 30.

[50] Zhang Wenjun, 6-7.

[51] Ho, 365.

[52] Lu, 67.

[53] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 22.

[54] Ibid., 7.

[55] Galikowski, 20.

[56] In his article, Joel Andreas points out that China’s educational system after 1949 continued to facilitate elite reproduction. See Joel Andreas, “Reconfiguring China’s Class Order after the 1949 Revolution,” in Handbook of Class and Social Stratification in China, edited by Yingjie Guo (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016), 27.

[57] Qian Junrui, “Stimulate Revolutionary Momentum, Promote Cultural Upsurge (鼓足革命干劲 促进文化高潮),” People’s Daily (Feburary 9, 1958): 3.

[58] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 211.

[59] Galikowski, 143.

[60] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 367.

[61] Ibid., 188.

[62] Ibid., 152.

[63] The Ministry of Culture of the Central People’s Government’s 1950 Report on National Culture and Art Work and the Main Points of the Plan for 1951 (中央人民政府文化部一九五零年全国文化艺术工作报告与一九五一年计划要点),” People’s Daily (May 8, 1951): 3.

[64] Jiang Feng, “Great Development in Art Work (美术工作的重大发展),” People’s Daily (October 11, 1954): 3.

[65] “Worker Newspaper Should Work Towards Popularization (工人报纸应该向通俗化努力),” People’s Daily (May 6, 1951): 6.

[66] Li, “Beginning from ‘the Red Flag Song.’” See also Song Enhou, “How We Organize Art Training Sessions (我们怎样办美术培训班),” People’s Daily (July 16, 1965): 6; Hua Xia, “Talking about Workers’ Art Tutoring (谈工人美术的辅导工作),” Meishu 10 (1958); Huang Pimo et. al, “Foster the Spirit of the Worker Class;” Cai Ruohong, “On Worker Art Creation (谈工人美术创作),” People’s Daiily (May 23, 1951): 9; “Worker Art is Thriving: On the Symposium on the Second Worker Amateur Art Exhibition (工人美术在蓬勃发展 记第二届工人业余美展座谈会),” Meishu 3 (1960): 24; “The Ministry of Culture and the All-China Federation of Trade Unions Jointly Issued Instructions on Further Developing Culture and Art work in Factories and Mines (文化部和中华全国总工会联合发布关于进一步开展工矿文化艺术工作的指示),” People’s Daily (December 17, 1955): 3.

[67] Xu Tianmin, “Nanjing Workers’ Mural Gallery (南京工人壁画廊),” People’s Daily (December 1, 1958): 8.

[68] Song Enhou, “How We Organize Art Training Sessions.”

[69] Cai Ruohong, “On Worker Art Creation.”

[70] Mingxian Wang and Shanchun Yan, The Illustrated Fine Art History of the People’s Republic of China: 1966-1976 [新中国美术图史: 1966-1976] (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House: 2014), 245.

[71] “The Ministry of Culture of the Central People’s Government’s 1950 Report on National Culture and Art Work and the Main Points of the Plan for 1951.”

[72] Zhou Yang, “Strive to Create More Excellent Literary and Artistic Works (为创造更多的优秀的文学艺术作品而奋斗),” People’s Daily (October 9, 1953): 3.

[73] Hua Xia, “Talking about Workers’ Art Tutoring,” 3.

[74] “The Cultural Revolution Promoted Workers’ Amateur Art Creation: Yangquan Workers Created Numerous Art Works and the Amateur Creative Team Continued to Grow (文化大革命推进工人业余美术创作: 阳泉市工人创作大量美术作品, 业余创作队伍不断发展壮大),” People’s Daily (February 5, 1974): 3.

[75] Hua Xia, “Talking about Workers’ Art Tutoring,” 3.

[76] Cai Ruohong, “On Worker Art Creation.”

[77] “Real knowledge Comes from Practice, Talent Grows through Struggle (实践出真知, 斗争长才干),” People’s Daily (October 30, 1974): 2. See also “Worker Art is Thriving,” 24.

[78] Hua Xia, “Talking about Workers’ Art Tutoring,” 5.

[79] Ibid., 5.

[80] Song Enhou, “How We Organize Art Training Sessions.”

[81] Wu Huikuang et al, “”Labor Daily” is a Good Teacher For Our Worker Art Workers (《劳动报》是我们工人美术工作者的好先生),” People’s Daily (October 17, 1952): 2

[82] “Tutoring work Leaping Forward: On the Teaching of the Workers and Peasants Art Training Class of the Central Academy of Fine Arts (辅导工作在跃进 记中央美院工农美术训练班的教学工作),” Meishu 10 (1958), 34.

[83] For instance, see Tang Yun, “To Reform in Labor,” 47; “Tutoring and Elevating (辅导与提高),” People’s Daily (July 16, 1965): 6; “Real knowledge Comes from Practice, Talent Grows through Struggle.”

[84] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 277.

[85] “The Capital Holds the Worker Amateur Art Exhibition.” In fact, all exhibitions of workers art held in 1955 across China focused on the representation of workers’ productive labor. See “Overview of Workers’ Art Exhibitions and Mass Art Activities in Various Places (各地工人美展和群众美术活动概况),” Meishu 3(1955): 47.

[86] “Worker Art is Thriving,” 21.

[87] Riksin, 82.

[88] “The Capital Holds the Worker Amateur Art Exhibition (首都举办工人美术创作展览),” People’s Daily (May 6, 1955): 3. In almost every worker art exhibition held before 1955 in various cities in China, cartoons were the overwhelming majority. See “Overview of Workers’ Art Exhibitions and Mass Art Activities in Various Places (各地工人美展和群众美术活动概况),” Meishu 3(1955): 47.

[89] Chen Su, “Further Develop Workers’ Amateur Art Activities (进一步开展职工业余美术活动),” Meishu 5 (1955): 17.

[90] “The Opening of the Second Worker Amateur Art Exhibition (第二届工人业余美术创作展览会展出),” People’s Daily (October 10, 1960): 4.

[91] “Worker Art is Thriving,” 25.

[92] Tong Heng, “Worker’s Comics.”

[93] Riskin, 149.

[94] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 206.

[95] For instance, see “Amateur Art Works of the Masses Exhibited in Shanghai (上海展览群众业余美术作品),” People’s Daily (October 19, 1961): 4; “Xi’an Amateur Art Creations Are Rich And Colorful (西安群众业余美术创作丰富多采),” People’s Daily, (March 12, 1962): 2; Lu Pu, “Chongqing Workers’ Amateur Art Activities (重庆市工人业余美术活动),” Meishu 3 (1963): 27; Zhang Xijin, “Amateur art creation must Follow the Correct Direction (业余美术创作必须遵循正确方向),” People’s Daily (July 16, 1965): 6.

[96] Ying Yi, Art and Artists in China Since 1949, trans. Bridget Noetzel (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 48.

[97] Zhang Xijin, “Amateur art creation must Follow the Correct Direction.”

[98] “Under the Guidance of Chairman Mao’s Proletarian Literature and Art Line, the Worker Class in Lüda Actively Carried out Amateur Creations (在毛主席无产阶级文艺路线指引下, 旅大市工人阶级积极开展业余创作),” People’s Daily (May 22, 1975): 1.

[99] Galikowski, 153. See “Create Works that Are Worthy of the Great Era. The National Art Work Conference Determines the Current Tasks of Art Work (创作无愧于伟大时代的作品 全国美术工作会议确定美术工作当前任务),” People’s Daily (December 5, 1958): 6.

[100] For instance, see Wen Ji, “New Achievements of Socialist Art Creation (社会主义美术创作的新成果),” People’s Daily (July 16, 1972): 4; “Joyfully Watch the Blooming of Revolutionary Literature and Art (喜看革命文艺百花盛开),” People’s Daily (March 29, 1976): 2.

[101] Huang Pimo et al, “Foster the Spirit of the Worker Class.”

[102] Tsang, 126-129.

[103] Mingxian Wang and Shanchun Yan, 197.

[104] Paul Clark, The Chinese Cultural Revolution: a History (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 208.

[105] Ibid., 213.

[106] Ho, 348.

[107] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 321; Galikowski, 154.

[108] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 250.

[109] Mingxian Wang and Shanchun Yan, 153. Children’s Palace originated in the Soviet Union for the extracurricular education of the youth. In Maoist China, training in Children’s Palace was a privilege reserved for the most talented young students in art, science, sports, or literature.

[110] Andrews, Painters and Politics, 359.

[111] Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, The Art of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 141.

[112] Galikowski, 25. Li Baoyi, “Give Full Play to the Propaganda and Educational Function of New Year’s Paintings (充分发挥新年画的宣传教育作用),”People’s Daily (December 1, 1975): 4.

[113] Kuiyi Shen, “Propaganda Posters and Art During the Cultural Revolution,” in Art and China’s Revolution, ed. Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian (New Haven, CT: Asia Society/Yale University Press, 2009): 154.

[114] Julia F. Andrews, “The Art of the Revolution: Chinese Prints 1930 to 1949,” in The Art of Contemporary Chinese Woodcuts, ed. Christer von der Burg (London: Muban Foundation, 2003), 32.

[115] Andrews and Shen, The Art of Modern China, 141.

[116] Li, Baoyi, “Give Full Play to the Propaganda and Educational Function of New Year’s Paintings.”

[117] Some, but not all people conducting militia drills were workers.

[118] Clark, 51.

[119] “New Good News on the Art Front (美术战线的新喜讯),” People’s Daily (November 10, 1974): 3. See also “Workers, Peasants and Soldiers Are the Main Forces of the Literary and Artistic Revolution (工农兵是文艺革命的主力军),” People’s Daily (November 6, 1974): 4; Huang Pimo et al, “Foster the Spirit of the Worker Class.”

[120] Wen Mei, “Great Art, Ode to the Times: Praise for the Shanghai, Yangquan, Lüda Worker Art Exhibition (伟大的艺术, 时代的颂歌: 赞《上海、阳泉、旅大工人画展览》),” People’s Daily (November 18, 1974): 3.

[121] Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 175.

[122] Ibid., 217.

[123] Ibid., 293.

[124] Clark, 52.

[125] Frank Dikötter, The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962-1976 (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2016), 90.

[126] Barbara Mittler, A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture (Harvard University Asia Center, 2012), 377.

[127] For instance, see Huang Pimo et. al, “Foster the Spirit of the Worker Class;”

[128] Lu, 79.

[129] Mao Zedong, “Instructions on ‘Learning the Instructions of the People’s Liberation Army to Strengthen Political Work’ (《关于学习解放军加强政治工作的指示》的批示),” first issued 1964 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL: www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/5-139.htm.

[130] Mao Zedong, “Firmly Believe in the Majority of the Masses (坚定地相信群众的大多数).” First issued October 13 25, 1957 and reprinted by Marxists.org. URL www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-19571013.htm

[131] Lu, 113.