Editorial | Fall 2025

Welcome to FIELD’s Fall 2025 issue. This has been an unusually challenging issue to finalize, due to the ongoing political and cultural crises that have been imposed on us by the Trump administration. We began developing our plans for a special series of FIELD essays on questions of censorship and dissent last winter, but we didn’t expect this topic to become so glaringly relevant quite so quickly. I’m writing this editorial following the second “No Kings” day protests, which have seen close to seven million Americans (and many others globally) demonstrate against the growing authoritarianism of the Trump regime. A number of events have unfolded over the past few months that reflect the urgency of this moment, including unprecedented governmental attacks on higher education (in California and nationally) as well as a troubling case of censorship at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. And on October 17 Karoline Leavitt, the White House Press Secretary, announced that the entire Democratic Party is “made up of Hamas terrorists, illegal aliens, and violent criminals”. We’re not yet at the point of jumping out of our windows, one step ahead of the SS, like John Heartfield almost a century ago, but we are getting perilously close.[1]

Our Fall issue includes three essays that examine the unfolding forms of censorship and repression that are at the core of Trump’s autocratic vision for America. They include an essay by FIELD Collective member Leila Abdelrazaq examining the incident at the Whitney which unfolded around a performance addressing the ongoing genocide in Gaza, commissioned in conjunction with an exhibition organized by participants in the Whitney’s Independent Study Program or ISP. Leila also addresses the subsequent termination of Sara Nadal-Melsió, the Associate Director of the ISP, after she protested this act of censorship. This incident demonstrates with great clarity, if any were needed, that Donald Trump could impose martial law in the U.S. tomorrow and the institutional art world would carry along quite happily. The kinds of products it demands might shift a bit, but the underlying infrastructure, and the class privilege that drives it, would continue without interruption. A second essay, which I’ve contributed, situates both the attacks on the UC system and the Whitney incident in the context of the powerful alliance between billionaires, Christian Nationalists and the far right that drives the current Trump administration. The third essay consists of a dialogue between Amelia Jones, an art historian and curator who teaches at the University of Southern California, and Ben Nicholson, an artist and researcher who teaches at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Amelia and Ben co-founded the System Failure initiative in 2023 to address, in their words, “the destructive neo-liberalization of higher education and arts complex institutions . . . in North America, the UK, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.” The System Failure project, which combines scholarly research with coalition building, offers an important model for how scholars and artists can develop new forms of critique and counter-institutional praxis, as they witness the ongoing right-wing assault on academia and the art world.

Our Fall issue also features an important set of essays and interviews focused on the role of artists and artistic practice in Ukraine in response to the Russian invasion of their country, a process which first began with the annexation of Crimea and Donbas in 2014. The not so hidden alliance between Trump’s America and Putin’s Russia is evident at many levels, most recently in Trump’s garish makeover of the White House as a gilded palace, like the dacha of some tasteless Russian oligarch. If we are living through the early phases of an attempted autocratic takeover in the U.S., Ukrainians are experiencing the militarized violence of a fully evolved dictatorship, bent on conquest and domination. Ukraine has a long and venerable historical tradition of resistance, which is being mobilized today across every level of society. The Ukrainian people are, quite literally, in a battle for their survival. They have been drawn together in this endeavor, which has called upon unparalleled levels of sacrifice, risk, and creativity among its people. The reality of war, and the honor with which the men and women of Ukraine are fighting it, is a stunning rejoinder to the cartoonish, adolescent “war fighter” rhetoric of Trump’s Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth. These essays were contributed by guest editor Valeria Radkevyich, a Ukrainian curator, writer and researcher, who generously offered to develop them for us. The first essay presents Valeria’s remarkable first-hand account of a camouflage workshop created in the Textiles department of the National Academy of Art in Lviv. Here, artists, faculty and community volunteers work together to craft camouflage netting to be used in the front lines of the war, in what Valeria describes as “a lifesaving art of resistance, care, and heroic invisible labor.” As Lviv Professor Olesya Datsko describes it, “When all of it started, when Russian tanks entered Sumy, Kyiv, everybody rushed over here. And everyone wanted to be useful, to do something. . . Here in the Academy, we had a little alumni reunion, because many important artists with careers came back to their Alma Mater to make camo nets.” This is just one among hundreds of similar spaces in Ukraine, which have undergone a transformation from art and cultural centers into sites of both practical work, contributing to the military defense of Ukraine, as well as emotional sustenance and community building, during a time of dire and ongoing threat.

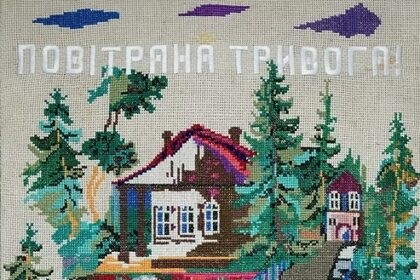

Valeria has also contributed two interviews. The first, with Peter Doroshenko, the curator of the Ukrainian Museum in New York, explores the complex cultural politics of Russian colonialist domination, and the ways in which art history and curatorial practice can contribute to a form of de-colonial cultural resistance. Russian imperialism isn’t simply manifested in its appetite for military conquest, but also in its drive to utterly efface the cultural identity of Ukraine itself. In the field of art history this occurs through a process by which Ukrainian artists are transformed into “Russian” artists in the wall labels of museums and the pages of art history books (a gesture of appropriation which many Western curators and art historians continue to be complicit with). In his work at the Ukrainian Museum Doroshenko has sought to undo this process, bringing new light to the unique features of Ukrainian culture, and the myriad ways in which it has informed a range of canonical Ukrainian artists (such as Malevich, Tatlin and Exter) as well as lesser-known figures. Valeria’s second interview is with Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova, who found her practice transformed by the experience of the war. During the early stages of the invasion she had to shelter for two weeks in her basement, eventually fleeing to western Ukraine. Through these experiences, as she observes, the focus of her work “completely changed”. She has developed a series of projects, including sculptural installations that incorporate artifacts found in burned out houses from villages in Donetsk, a series of embroidered folk-art tapestries that she detourned with new language referencing the war, and tactile sculptures made from river rocks which resemble traditional Ukrainian bread. Early on she made the decision to donate the profits from the sales of these works to support the Ukrainian military and humanitarian groups, and she has now raised seven million Hryvnia (equivalent to almost $170,000).

The final section of essays for our Fall issue includes a series of three reports on the growing threat posed by global authoritarianism. This is the third installment in Greg Sholette’s ongoing series of commissioned reports from artists, critics, curators and theorists working across the world. They provide a sobering counterpoint to the increasingly autocratic conduct of our own government here in the U.S. In this issue we present Sandip Luis’s report from India, Kim Charnley and Isabel Lima’s report from the United Kingdom, and Lara Fresko’s report from Turkey. Greg provides his own introduction to the reports here. I am especially proud of this issue of FIELD, and very grateful to our contributors. I want to express my special gratitude to Valeria Radkeyvich, for her work on the Ukrainian essays. This issue exemplifies, for me, the remarkable potential for scholarship on engaged art practice, and its ability to operate across disciplinary boundaries to illuminate the complex political, cultural and artistic dynamics at work in today’s world; a world increasingly defined by a global struggle against authoritarianism and neo-fascism.

Grant Kester

FIELD is available at: www.field-journal.com

[1] See John J. Heartfield and Lance Hansen, “The Night the Nazis Came to Murder My Grandfather,” The Nation (April 5-12, 2021). https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/john-heartfield-photomontage-nazi/