Social Practice Art and the Problem of Efficacy

Text by Eva Marxen and David Gutiérrez Castañeda

Image curation and footnote annotations by Alfadir Luna

Introduction: Symbolic Capital, Philanthrocapitalism, and Metrics

Within the tenth anniversary issue of FIELD, dedicated to the crucial subjects of socially engaged art and criticism, this essay deals with the institutional critique of social practice art. Concretely, we seek to investigate the controversial questions of “scope”, “usefulness,” and “impact” of what is broadly denominated as “social practice art.” Our intention is to analyze these issues beyond political and capitalist pragmatism. This is especially important because frequently social artistic practices that may include socially engaged art, relational art, participatory art, community art, and art activism,[1] are used for institutional politics of publicity and capitalist purposes.

In the first case, institutions gloss social engagement over themselves to appear as social benefactors to their publics, eventually hiding the violent essence of their institutionality, such as it may happen in jails. In the second, banks, corporates, insurance companies, etc. veil their equally violent capitalist dynamics with their foundations dedicated to the arts and culture. In both contexts, the intention consists of accumulating symbolic capital in the sense of Bourdieu: they gain positive validation and appraisal for their supposed cultural commitments, so that citizens consider them as “good” or even indispensable for society.[2] Thus, they accumulate symbolic capital in the form of positive publicity and press. At the same time, they can hide unpopular capitalist and institutional dynamics behind. For example, jails appear as places where inmates are given facilities for culture, while forced in inhuman conditions, including torture. Banks seem socially engaged in culture while they are mercilessly evicting people from their houses and enforcing foreclosures. Private art schools encourage or even claim socially engaged art practices by their professors and students that appear as altruistic, instead of revealing their capitalist business that gets their students in debt for the rest of their lives. In the same vein, they rely on a cheap adjunct labor force. Additionally, they invest in real estate, including gentrification and speculation, sometimes with the help of these social art practices.

The investment in “social” art practices ultimately pays out in economic gain, although not at the first glance, nor with a fixed exchange rate. Yet, with the accumulation of symbolic capital, fundraising becomes more efficient. In this sense, decision makers of banks, corporations, and their foundations can convince politicians of the need for more subsidies, art schools attract more students and earn more tuition. Additionally, both for-profit and non-profit organizations benefit from tax reduction for their social and cultural investments that, indeed, can be calculated in exact numbers.

The exhibition level, whether virtual or in person, is crucial for the accumulation of symbolic capital. That is when publics are exposed to the concreteness of their social investment that they sell with all their branding and marketing expertise. Corporate public relation agents themselves, concretely from Exxon, have called these phenomena “social lubricant.”[3]

Recently, the acceptance of “unethical money” by art institutions has been called “art washing” and has included donors involved in sex and arms trafficking or big pharma corporations responsible for the opioid epidemic.[4] The institutions themselves measure their activities quantitatively, monitoring the numbers of hits, ‘likes,’ followers, visitors, ticket sales, rentals, quotations, spectators, grant and donation income, without any concern about the spectators’ or followers’ personal experiences.[5] Instead, “experience” is converted into excel-sheet numbers, treated as a commodity and “consumed by the relentless processes of capitalism.”[6] The consequences are a neoliberalist imposition of economic values and the “language of accounting,” as well as assessment systems that “have to justify themselves according to metrics.”[7]

Since the beginning of this millennium, so-called “philanthrocapitalism” has boomed.[8] The term stands for the fusion of business with philanthropy, a penetration of finance and technology capitalism into charity with the purpose of converting the latter into a business and gaining the maximum benefit from it. Venture philanthropy mirrors venture capitalism. Both obey the rules of the market, with its risks and gains. Philanthrocapitalism has replaced traditional donations. It is subject to capitalist efficiency and usually organized as family or corporate foundations that aim at triple benefits: (i) symbolic gain in form of positive publicity, (ii) economic advantage because of tax saving and additional investment in the philanthropic market, (iii) political reward in the mode of co-governance by gaining influence in public politics. This influence can become so strong that eventually impunity for the corporations behind the foundations is achieved.

Institutional Critique of Social Practice Art

These instrumentalizations of the arts have been criticized by many artists and theorists, especially by those engaged with institutional critique.[9] They critique the political condition of the production, funding, distribution, and reception of art by official artistic institutions. Hans Haacke,[10] to mention a “classic,” has dedicated his entire professional life to this way of art making and theorizing. Other important artists who have worked in the line of institutional critique are Martha Rosler,[11] the Guerrilla Girls,[12] Joseph Kosuth,[13] Adrian Piper,[14] Roberto Jacoby,[15] Fred Wilson,[16] Andrea Fraser[17] and Rogelio López Cuenca,[18] just to name a few. Some examples of theorists, writers, and critics are Gerald Raunig,[19] Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson,[20] Claire Bishop,[21] Laurent Cauwet,[22] Karen Archey, [23] and Melanie Bühler.[24]

Both in her texts and artworks, Fraser[25] has repeatedly shown the contradiction of institutional critique, its own institutionalization and absorption by neoliberalism. As a matter of fact, the art world is a multibillion-dollar business. Art institutions (museums, galleries, art schools, art events, etc.) have adapted neoliberal dynamics, including exploitation of their staff, forming part of the “service economy of contemporary capitalism.”[26]

It is a bold contradiction if neoliberal institutions claim radical politics, critiques or even “social justice.” This is especially absurd because these practices take place in institutions that are run by some of the wealthiest people of the world who weaken state tax income and public services with their art washing. Extreme wealthiness derived from capitalism cohabitates with the underpayment and abuse of artists and art employees, reaching extremes with the attempts to repress unionization campaigns.[27] This has led to perverted contradictions between exhibitions about accessibility and diversity without fostering either access or diversity in the institution’s staff;[28] or exhibitions and programs about the fashionable subject of ‘care’ and the anti-care labor relationships and institutional politics.

Fraser urges an unsparing self-critique of the critiquing artist who inevitably forms part of this art capitalism, especially since artists need these very institutions to develop, show, and disseminate their work. Fraser advocates for an institutional critique that judges “the institution of art against the critical claims of its legitimizing discourses, against its self-representation as a site of resistance and contestation; and its mythologies of radicality and symbolic revolution.”[29] The breach between the discourse of critical art with its claim for social change and the material conditions of that same art are evident, as is the gap between critical art’s pretension of meaning and its social and economic being,[30] between representation and material realities.[31] Referring to Bourdieu[32] and Freud,[33] Fraser shows the continued negation of the structural dependency between art and its social and economic conditions.[34]

Fraser argues within a US context where hardly any institution or practice is exempt from neoliberalism. Haacke explained already in 1974 that artists “work within that frame, set the frame and are being framed.”[35] Art institutions perpetuate the same oppressive systems that are frequently critiqued in the artworks they exhibit.[36] In this context, one of the only possible conclusions is to develop a method of “critically reflexive site specificity” that relentlessly shows these dynamics and contradictions.[37]

Fraser frequently quotes Bourdieu who has reminded us that intellectuals, and by extension artists, are “holders of cultural capital,” and as such they “are a (dominated) fraction of the ruling class, and that many of their positions, in politics for example, are due to the ambiguity of their position as the dominated among the dominant.” Furthermore, the condition of “belonging to the intellectual field implies specific interests, […] academic posts or contracts for editing reports or positions at universities, but also signs of recognition and gratification, often imperceptible to those who are not members of that universe, but through which all kinds of subtle constraints and censures are made possible.”[38] The alternative of a self-reflexive institutional critique would be the withdrawal of artists, art historians, art theorists, critics, curators, etc. from the art market together with all their cultural capital.[39] The latter strategy resembles the withdrawal or exodus position, as articulated by Virno or Hardt and Negri.[40] They defend an “exodus” from all institutions: “This strategy of evacuation of the places of power is justified by the claim that, under post-Fordist conditions of cognitive capitalism, desertion is the only form of resistance to the immanence of biopolitical capitalism.”[41]

By contrast, Gramsci’s “war of position” means engaging with all possible crucial institutions of art and culture in order to profoundly change their functioning from “within.” This means targeting “the nodal points around which the neoliberal hegemony has been established, so as to disarticulate the key discourses and practices through which it is sustained and reproduced.”[42] These aforementioned discourses comprise the economic, social, political, cultural, legal, and environmental.[43] The canon of institutional critique has been Euro- and US-centric from its very beginning. Within this centrism, the very first wave was made up mainly of white men, such as Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, and Hans Haacke. The foundational texts have equally been authored by mainly white American or European men and women. The origins of institutional critique have been traced back to the (again) Western framework of conceptual art[44] and its dematerialization of the artwork.[45] Yet, in Argentina, Oscar Masotta operated with this term in the same year as the supposed pioneer Lucy Lippard.[46] In the Latin American context, while institutional critique is often associated with the emergence of a certain form of critical conceptualism;[47] referencing the canonical collective cultural intervention Tucumán Arde (1968), carried out across the province of Tucumán, Rosario, and Buenos Aires in Argentina,[48] this work can be understood as operating at the intersection of representational management and political critique, involving trade unions, activists, communicators, and artists. Although this endeavor emphasizes “critique” and “politics” within a society shaped by artistic intervention, it continues to essentialize the effectiveness of the individual artist’s ingenuity. In response, following more than fifty years of debate in Latin America, a shift has taken place towards what scholars such as Tomás Peters and Carla Pinochet Cobos have termed a “Situated Cultural Democratization” in the early 21st century.[49] This implies a political understanding of artistic processes embedded within frameworks of cultural management, audience recognition, and the cultivation of critical culture in alliance with social movements and situated, delimited agendas. Artists operate within webs of inter-institutional alliances, even intervening in the symbolic and prestige-oriented logics of those institutions themselves,[50] constituting artistic labor as a mediator of interests and representations aimed at articulating the cultural processes of concrete political subjects.

Nevertheless, in the context of peace and memory mediation in Colombia at the beginning of the 21st century, David Gutiérrez Castañeda reflects:

I have learned that when one insists on de-installing the foundations or, perhaps, on raising the question of why certain artistic practices are pursued as an advance toward coexistence, I have often encountered a resistant attitude from interlocutors—frequently thoughtful and active agents. There is a set of established truths I try to describe here, which frequently evade concrete discussion, in my view, because they reproduce a series of highly ambiguous social imaginaries about what art is capable of. These discourses, particularly within academic spheres, provoke friction and discomfort, because through these utterances arguments are made that operate politically while simultaneously avoiding categorical confrontation, producing a certain idea of redemption. They are used as defense and justification, often installing a moral framework that cancels critical questioning. I will not be able to recount the cultural history of these imaginaries here—much less their genealogy.[51]

His notion of “Redemptive Narrative,” inspired by Elizabeth Povinelli’s queer anthropology,[52] helps us to understand how these processes of cultural democratization through a post-autonomous art[53] —an art that simultaneously operates as cultural manager, professional labor, and promoter of aesthetic experience—bring to light the legitimizing tensions and aspirations for social equity that seek to shape a form of political art within what George Yúdice[54] refers to as “Culture as Resource.” Furthermore, as Ticio Escobar reminds us:

Although art increasingly finds its circuits co-opted by the logic of mass spectacle, its minority tradition has not only led to aristocratic exclusivisms, but has also enabled it to protect the darker zones of collective experience, to mobilize historical imaginaries, and to complexify the matrices of social sensibility. Therefore, while denouncing the elitism of [critical] avant-gardes, their authoritarianism and redemptive vocation, one should also reclaim their fertile moment and recover their valuable contribution. This restorative operation could invoke art’s minority character under the aegis of the recognition of difference proclaimed by our present.[55]

In this spirit, the Indigenous artist and anthropologist Glicéria Tupinambá,[56] in Brazil, has developed a series of material, performative, and inter-institutional inquiries to assert the importance of the feather cloaks looted in the 16th century from the Tupinambá peoples. The critical recovery undertaken by the artist activates not only communal and ritual practices, but also symbolically densifies the operations of instituting violence—not only of culture, but of the state itself. Her critique does not exhibit the vanity of disqualifying judgment or the mere denunciation of hegemony. Rather, it insists on reclaiming what is owed, generating a fertile moment of communal resilience.

The second wave of Western institutional critique targeted the museum’s Eurocentric and colonialist roots, together with its colonialist ways of representation and collections. According to Archey, the “production and institutionalization of knowledge itself” was reassessed, “and by extension the entire [art] field.”[57] Yet, Bühler has reminded us, that it has remained paramount to rethink institutional critique’s “traditional parameters and lineage” until today.[58] There is a need for rewriting its beginnings and present expansion by “untooling” the colonialist canon, including geographically.

The canon has indeed expanded beyond the museum, considered as the first target of Western institutional critique. The third “generation” of canonized institutional critique had already dealt with “their surrounding material reality,” including “the very conditions of life.”[59] Institutional critique is not more bound to a tangible object, a certain space or site. It has penetrated “socio-political organizations of contemporary life.”[60] ‘Sites’ can be understood as social, cultural, political, economic, environmental, or even discursive, embracing “repressed ethnic history, a political cause” or “redefining the public role of art and artists.”[61] In this sense, institutional critique can be considered an extension of critique on governance as outlined by Foucault.[62] Foucault focused on how we are governed, rather than the fact that we are governed. This means for institutional critique to address subjects such as public services (i.e. health care and cultural institutions), as well as their privatization, commodification, and gentrification.

However, this frequently entails an analytical consideration of the arts without sufficiently addressing the ways in which they are configured within the practices and orientations of the cultural policies that frame them. As Jon McKenzie suggests in his analysis of performative effectiveness, the social aspirations of an artistic endeavor cannot be understood independently of the illocutionary context in which its expectations are formed.[63] The effect of an artistic operation is not conceivable without a pre-existing desire for its performance; that is, its efficacy is not merely discursive but shaped in advance by values and forms of evidence deemed valid. This dynamic is likely present in much of what is today categorized as political art, institutional critique, or socially engaged practice. This performativity produces the indicators and tangential elements that signal the presence of evidence regarding the effects of artistic interventions.

Such a recognition implies the need for a critical dismantling, one that may benefit more from sociological and social science tools than from philosophical frameworks—tools that have traditionally dominated the genealogies of institutional critique. Scholars such as Ribalta and Marxen[64] have emphasized the importance of analyzing these operations of dismantling from within social practices, paying closer attention to community articulations and their transformations than to the ideas or intentions of individual artists.

Social art practices have undergone a similar fate. Although many of them claim to escape or transcend “the commodity conditions of art,”[65] they have frequently been co-opted by philanthrocapitalism, the accumulation of symbolic capital, art washing mechanisms, and ultimately the commodification of the service industry, “the prevailing episteme of a late capitalist, tertiarized society.”[66] In this regard they have undergone the same subsumption as Western conceptual art and its dematerialization of the art object. In spite of its efforts, it did not succeed in transforming the political economy of art but was quickly commodified by the capitalist market. All these dynamics render critical dismantling improbable. The normalization of the efficacy of social practice does little to help us understand the poetic dynamisms and generative tensions that can activate cultural life.

In contrast to commodified and co-opted contemporary social art practices, we are interested in artistic interventions capable of facilitating processes of subjectivation, collective emergence, and participation—beyond quantitative metrics and neoliberal tempos. Following Ribalta, the practices we foreground should go “beyond the regime of visibility, whose paradigm is the exhibition,” and should work to restore “forms of subjective appropriation of artistic methods in processes located at the margins and outside” of official art institutions.[67] This is particularly important because the exhibition space tends to transform processual practices into consumable objects. There is a fundamental contradiction between antagonistic, procedural, and experimental practices—those that seek to explode established institutional frameworks and disciplinary boundaries—and the institutional logics that monumentalize and codify them. This contrast lies, as Marxen and Ribalta argue, “between subjective forms of appropriation and practice of artistic methods and knowledge, and the institutional-exhibitionary monumentalization of such practices.”[68]

Intangible Efficacy

By definition, processes that are genuinely subjective and collective resist authorization by any singular or “correct” method of representation. If they are to be represented at all, it must be by the participants themselves—not by external figures of authority such as curators. Subjective processes, once framed within institutional exhibition formats, risk becoming fossilized or sterilized. For this reason, there is a critical urgency to dismantle the logics of “sovereign, disciplinary, and liberal power apparatuses,” and to question the premise that the exhibition is the primary moment “when the artistic project is valued in our society.”[69]

In this sense, what we propose to consider as social artistic practice is a set of actions and performativities situated in specific sociocultural dynamics, in which affects, symbolizations, and materializations are deployed that entail relationships between people, territories, human, and more-than-human ecosystems.[70] The dynamics become procedural and unstable, considering that their representations are part of the same configuration of the artistic processes and are not held by the artist as an author, but rather by practices the community will consider. These can always be rethought and renegotiated according to the tone and commitment of a diverse order that involves these agents.

We can lean on critical Indigenous studies, where “intangible efficacy” goes much beyond the western imperative of visibility and marketing, quantitative “facts,” and the capitalist doctrine of the accumulation of symbolic capital. In this framework, art is not the representation of life, but performative, as it is an extension of the individual as well as the collective body.[71] The notion of “intangible efficacy” disrupts McKenzie’s concept of performative efficacy.[72] Artistic practice does not emerge from an expectation of evidence or performance; therefore, it does not conform to or accommodate itself within discourses of impact, redemptive narratives, or idealized social interventions. are other-than-human agents that have their own agency. As such they can reach a broader political sphere, beyond the individual, with “the potential to produce anti/de/non-colonial utopian performatives for participants.”[73] Consequently, collective agency is experienced as vibrant fullness, hope, and “affective power.”

Similar thoughts have been articulated in a European context of left-wing political resistance by Negri and Guattari.[74] Based on Marx, the social transformation is inevitably linked to the personal and vice versa. By changing social conditions, the individual feels empowered as does the collective. This power can achieve social change if it is channeled by political organizations.

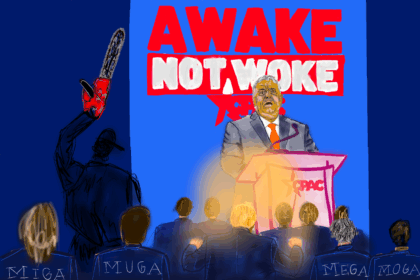

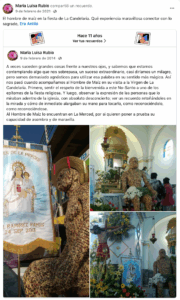

As shown in the curated images of memory and companionship surrounding the Hombre de Maíz, selected for this text by Alfadir Luna, there are underlying narratives and values. However, these do not align with prefigured social conflicts or necessary transformations. Rather, they represent a series of persistent gestures that generate ecosystems of practice and emergent experiences among diverse individuals, atmospheres, relationships, and intentions. There are no programmatic objectives—only incitements and provocations.

Case study: The Corn Man

As a conceptual axis, we present the work of Alfadir Luna, specifically El Hombre del Maíz (The Corn Man, 2008–2018), to explore the intangible effects of cultural and community practices from a poetic, anticolonial, and anti-capitalist perspective. The Corn Man has constituted a long-term community art project in La Merced Market in downtown Mexico City. It illustrates the convergence of local rootedness and resistance against systemic capitalist, colonialist, and patriarchal domination. From the first crescent moon of October each year between 2008 and 2018, a group of vendors (locatarios) from the Historic Center Markets of Mexico City carried a sculpture of a man entirely made from the diverse varieties of corn that grow in Mexico. His skin is made of corn. In a seated position, the figure is carried in procession from market to market, accompanied by dozens of people: there is a brass band, chinelos dancing in celebration of the harvest, and several market leaders acting as stewards and guardians of the symbol. The Corn Man visits each of the eight interconnected markets of the Historic Center, then resides for a year in one of them.

This initiative was inspired by the provocation of the Seminario de Medios Múltiples [Seminar of Multiple Media], devised by José Miguel González Casanova for the Arts Program at the UNAM Faculty of Art and Design, in which Alfadir Luna participated in 2007. The Medios Múltiples proposal explores the relational status of the arts, experimenting with artistic practices that blur or disrupt the boundaries of everyday life. Recognizing that markets are places of juxtaposed experiences—rich in aesthetic sensibility, color, form, flavor, and both economic and symbolic exchange—Luna initially began with a drawing exercise to diagram this complexity. What he ultimately found was a living diagram—tied to over fifty years of communal debates and tensions among the market vendors in what is Mexico’s third most important market circuit and the only one with cultural heritage status. His artistic proposal evolved into a living activator of relationships and a challenge to conventional understandings of art: rather than deciding its subject in advance, Luna engaged in long conversations with market leaders about the cultural life of the markets. He perceived that unity and trust among vendors were fragile, impacted by gentrification, political conflict, organized crime, family disputes, and lingering negative memories. Community recognition had to be earned.

In response to the question, “What could we do?”—raised repeatedly in his dialogues with vendors—Luna proposed a “secular ritual” to intervene in long-stagnant conversations that affected the very fabric of communal life. As he reflects: “The paper fibers are like social ties, and you leave things behind over time. I remember one afternoon clearly—this is where I realized what I wanted to do with my artistic practice. After a repetitive project where I tried to understand my own frameworks of thought, I came to see that art functions not necessarily to reveal knowledge, but rather procedures—sensitive, intuitive, logic-defying procedures.”[75] In another interview, he adds:

Medios Múltiples art needs collective experience. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a community intervention to resolve conflict, but rather something closer to a mode of coexistence… In my case, it was about a shared question. My generation leaned toward art that differentiates itself—some called it ‘metalanguage’—but that wasn’t the aim in Medios Múltiples, nor was it about bringing social intervention into the market. There’s jest, laughter, the patronal festival—but also the sales discourse, not just in how they sell, but in how they negotiate value. A hyper-regulated market is no market at all. What some see as chaotic is actually vibrant freedom. Each vendor makes their stall their own: arranges products, adds lights, installs altars, gives it vitality. For me, this incited the relational inquiry of Medios Múltiples—to intervene in its vitality. If art is representation, to what extent is participation also an image, and how does that manifest? That’s what The Corn Man procession is about.[76]

In this sense, the procession remains a project of art and participation not as Luna’s own, but as one conceived within a community in which he took part. He sees himself as a mediator of the experience. The represented are not subordinated to the artist; rather, they represent themselves and define authorship collectively. Markets are social institutions that foster citizenship, sociability, and community bonds—unlike sterile supermarkets that lack such interaction. They are both cause and effect of cities and have therefore been the focus of urban planning policies that alternately enable or suppress cultural participation.

La Merced Market is located in the downtown district of Mexico City. It is the city’s largest retail market and has roots in pre-Hispanic times when the area was already a major trade center. Today, La Merced represents a site of resistance to technocratic designs, development policies, and gentrification projects.[77] A century ago, market vendors opposed the modernist discourse that equated progress with regulation and discipline. The elites sought to dominate the subaltern through bourgeois values, despising informal economic practices. Yet, La Merced remains a space where popular culture thrives—rich in diversity, traditions, reciprocity, knowledge, and cultural encounters.[78]

As shown by Tassi and colleagues,[79] market vendors across Latin America do not merely conform to global economic norms; they define their own commercial logics and circuits, operating outside the frameworks prioritized by conventional economic analysis. These practices often subvert traditional class hierarchies and create “off-the-map” economies.[80] Market actors build public space anchored in local dynamics that transcend national state structures. Tassi et al. describe this as a “peripheral centrality.”[81] Far from being passive victims of globalization, they construct market niches “in the shadows of globalization,” shaping these spaces through history, tradition, and social networks—thus challenging elite economic authority.[82] Their organizational structures have proved more adaptive to crises, largely thanks to strong kinship-based social capital.[83] As Luna observes:

It’s like the will of the market itself—it behaves like a living organism, an urban stain where many kinds of markets coexist: formal, informal, fruit vendors, vendors of all kinds. In fact, I think La Merced is the third most economically significant market in Mexico—after the Stock Exchange and the Central de Abastos. It’s an economy based on manual labor, early mornings, product arrangement, local setup, coordination. It’s a deeply popular life, now maintained even by the great-grandchildren of original vendors. Yet, for many from the upper middle class, the popular idiosyncrasy of the market no longer aligns with their aspirations… I use a complex term here: a cosmo-technic. That’s why I make diagrams—ritual, mythological, cosmological—to understand survival within market practices. That’s the insistence behind The Corn Man—his symbol, his date, his procession. It’s not arbitrary—it seeks to make sense of the market’s cycles.[84]

The social capital displayed by La Merced actors includes the reinforcement of ethnic identities and the renewal of festive and religious practices that sustain local power structures.[85] It is precisely at this point that Luna’s artistic work is inserted. As an artist, he locates himself in an alternative genealogy descending from colonial-era economic-religious systems. His work integrates historical awareness and anthropological sensitivity.[86] As Luna affirms: “Rituality can be open, poetic. Rituals allow for that. They’re punctual, not based on a sacred book or a rigid dogma. We follow a ritual intuition, not a fixed belief system. So, there can be no tightly defined cult—only a practice.”[87] Unlike the highly mobile Aymara traders studied by Tassi et al.,[88] La Merced is a national economic enclave. As Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui notes,[89] it reveals a mestizaje of identities—a layering of diverse genealogical practices forming an incongruous yet collective deployment. Luna’s insistence lies in exploring this mestizaje, shaping a sufficiently complex symbol generated through local collaboration and ritual bonding. The Corn Man becomes a communal act.

In contrast to capitalist market logic, El Hombre del Maíz emphasizes participation, cultural production, and symbolic economies as being essential to local market communities. With the support of market stewards (mayordomos), Luna helped to create a meaningful symbol—the Corn Man—through a decade of conversations and narrative wagers. For the very beginner, the artist had conceived the art project for a duration of ten years. Stewardship is central to the project’s communal organization and spiritual protection. Narratives around organic corn, precolonial exchange systems, sacred plants, and the foundation of Mexican food culture were activated during processions held each October from 2008 to 2018, blending religious and secular elements rooted in central Mexican communal traditions. These performances lacked a formal script or purpose, functioning instead as relational experiments between merchants, leaders, neighbors, and allies to inhabit broad discussions about the political and symbolic meaning of markets.

Denouement

We consider this proposal to possess intangible effectiveness, as it resists co-optation by institutional frameworks of cultural programming. Instead, it weaves complex relationships that—while difficult to represent—have a real impact on the market’s relational dynamics. Today, El Hombre del Maíz has a niche next to the Virgin of Guadalupe inside the market and is watched over by its vendors. El Hombre de Maíz honors pre- and anti-colonial trade and community traditions. At the same time, it strengthens anti-capitalist market dynamics as opposed to its neoliberal instrumentalizations. It does so in a poetic, undogmatic, intangible manner, beyond any metric accountability, contributing to, instead of authoring, the empowerment of the market community. As we discussed above, the intangible efficacy of the Hombre del Maíz process does not imply the absence of processes, insistences, or the articulation of social experiences. Rather, it suggests that these are not preconceived through interventionist values or narratives. While expectations do exist, they are not assimilated into the habitual corporate uses of social practice, nor into the state’s justificatory appeals regarding cultural work.

Thus, El Hombre de Maíz may serve as an example in how far art can be socially engaged in opposition to colonialist exploitation and capitalist instrumentalization, the key issues we have analyzed in our institutional critique of social practice art. In order to achieve this, social practice art needs to denounce capitalism and colonialism in both theory and conceptualization, as well as practice and performance.

Eva Marxen is an anthropologist (PhD and DEA), art therapist (MA), and psychoanalytical

psychotherapist (MA). She has worked as an academic in Europe, USA, and different Latin American countries, mainly in Chile and Mexico. Additionally, she has been an invited researcher at the University of the Philippines Diliman, Manila. She has published numerous articles in books and journals in different languages and has held conferences as well as workshops at a national and international level. In 2011, Marxen published Dialogues between Art and Therapy (Gedisa). Her PhD thesis was published online (2012). Her book Deinstitutionalizing Art of the Nomadic Museum was published in 2020 by Routledge. In the same year, she edited the special bilingual issue “Learning Art and Resistance from the South” for Field: A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism. For over two decades, she has inquired into the confluences between contemporary arts and ethnography along with the arts as a form of resistance, with a special focus on Latin America.

David Gutiérrez Castañeda is a sociologist from the National University of Colombia (2006), Master (2011) and Doctor (2016) in Art History from the National Autonomous University of Mexico with emphasis on performance studies, gender, ecology, art, museology and politics in Latin America. In his doctoral research, Exercises of Care: About The Skin of Memory, he investigated cultural and artistic performances as a practice of care. He is Full-Time Associate Career Professor in the Bachelor Degree in Art History at the National School of Higher Studies Unidad Morelia (ENES) of the UNAM, of which he has been coordinator in the years from 2019 to 2020 and from 2023 to 2024. There he implements the Seminar on Performance Studies and Living Arts (SepaVivas) and the artistic residency program. He is a member of the research collective Taller de Historia Crítica del Arte and the Red de Conceptualismos del Sur. He has been a visiting professor at the Faculty of Arts of the National University of Colombia in 2018, in addition to the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany, the State University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and the National University of San Martín in Argentina in 2023. He is the winner of the National Prize for Art Criticism from the Ministry of Culture of Colombia in 2010 and the National University Recognition for Young Academics in Research in Arts at the UNAM in 2022.

Notes

[1] Note that these denominations stem from a US context and cannot be applied globally. Artist Alfadir Luna presented his work that we describe below as “social practice” to a US public within his participation in the Talking to Action exhibition (Kelley Jr. & Zamora, 2017). Yet, according to himself, his work reaches beyond these frames.

[2] Bourdieu & Haacke, 1995.

[3] Haacke, 2009, p. 286; Marxen, 2020a.

[4] Archey, 2022a & b; Keefe, 2021; ArtForum, 2019, and see the advocacy platform P.A.I.N., founded by artist Nan Goldin: https://www.sacklerpain.org/

[5] Bühler, 2022.

[6] Bühler, 2022, p. 33.

[7] Bishop, 2013, 61–62; Marxen, 2020a.

[8] Olivé, 2024.

[9] See for different classification and chronologization of three waves of institutional critique: Archey, 2022a; Raunig 2004; Steyerl, 2009.

[10] Hans Haacke 1975, 1995, 2009, 2012; Bourdieu & Haacke, 1995.

[11] Martha Rosler, 1998.

[12] Guerilla Girls,1998, 2003.

[13] Joseph Kosuth, 2002.

[14] Adrian Piper, 2003.

[15] Roberto Jacoby, 2011.

[16] Mignolo, 2011.

[17] Andrea Fraser, 2016.

[18] Rogelio López Cuenca, 2019.

[19] Raunig, 2004.

[20] Alberro and Stimson, 2009.

[21] Bishop, 2013.

[22] Cauwet, 2017.

[23] Archey, 2022a & b.

[24] Bühler, 2022.

[25] Fraser, 2005, 2016

[26] Medina, 2016, p9.

[27] Archey, 2022a; Bühler, 2022; Fraser, 2016.

[28] Archey, 2022a.

[29] Fraser, 2005, p. 283; 2016.

[30] Fraser, 2016.

[31] Archey, 2022a.

[32] Bourdieu, 1993.

[33] Freud, 1925/1999.

[34] Fraser, 2016.

[35] Haacke, 1983, p. 152; Archey, 2022a, p. 52.

[36] Archey, 2022a.

[37] Archey, 2022a & b, p. 41; Fraser, 2016.

[38] Eribon, 1980/2006-2008, translated by ourselves.

[39] Fraser, 2016.

[40] Virno (1996) or Hardt and Negri (2009).

[41] Mouffe, 2012, p. 270; Marxen, 2020a.

[42] Mouffe, 2012, pp. 270–271.

[43] Marxen, 2020a.

[44] Archey, 2022a.

[45] Fraser, 2016.

[46] Longoni & Mestman, 2004; Lippard & John Chandler, 1968; Longoni, 2017; Masotta, 1969; Marxen, 2020b

[47] (Mesquita et al., 2015.

[48] Longoni & Mestman, 2004.

[49] Tomás Peters (2020) and Carla Pinochet Cobos (2024).

[50] García Canclini, 1979.

[51] Gutiérrez, 2017, p. 325.

[52] Elizabeth Povinelli, 2011.

[53] García Canclini, 2010.

[54] George Yúdice, 2002.

[55] Escobar, 2015, p. 105.

[56] The artist’s process can be reviewed in this 2021 documentary video by Funarte Brasília: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9eB-2MBYOjY

[57] Archey, 2022a, 59.

[58] Bühler, 2022, 24.

[59] Archey, 2022a, p. 78.

[60] Kwon, 2002, in Archey, 2022, p. 64.

[61] (id.).

[62] Foucault, 2024; Archey, 2022a; Raunig & Ray, 2009.

[63] Jon McKenzie, 2000.

[64] Ribalta (2010) and Marxen (2020a).

[65] Archey, 2022b, p. 52.

[66] Fraser, 2016, p. 236, translated by ourselves.

[67] Ribalta, 2004.

[68] Marxen (2020a, p. 40) and Ribalta (2010, p. 256).

[69] Holmes, 2006, pp. 146, 166; Marxen, 2020a.

[70] Gutiérrez, 2017.

[71] Martin, 2013.

[72] McKenzie, 2000.

[73] Magnat, 2022, p. 35.

[74] Negri (2017) and Guattari (1977).

[75] Interview with Alfadir Luna. February 17, 2025.

[76] Interview with Alfadir Luna. 25, 2025.

[77] Cartagena, 2017.

[78] Cartagena, 2017.

[79] Tassi et al., 2012, 2020.

[80] Tassi et al., 2020; Robinson, 2002.

[81] Tassi et al. 2020, p. 23.

[82] Tassi et al., 2012, p. 97.

[83] Bourdieu, 1980; Fraga, 2014.

[84] Interview with Alfadir Luna. February 17, 2025.

[85] Tassi et al., 2012.

[86] Fraga, 2014, p. 79.

[87] Interview with Alfadir Luna. February 17, 2025.

[88] Tassi et al. 2012, 2020.

[89] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, 2019.

References

Alberro, A., & Stimson, B. (Eds., 2009) Institutional Critique. An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Archey, K. (2022a) After Institutions. Berlin: Floating Opera Press.

Archey, K. (2022b) “Karen Archey in Conversation with Andrea Fraser,” In M. Bühler (Ed.), The Art of Critique, pp. 40-52. Milan: Lenz Press.

ArtForum (News Desk). (2019) “Nan Goldin and P.A.I.N. Group Protest Sackler Family at the Guggenheim”, In ArtForum Newsletters. Retrieved from: https://www.artforum.com/news/nan-goldin-and-p-a-i-n-group-protest-sackler-family-at-the-guggenheim-242190/ [Accessed May 1, 2025].

Bishop, C. (2013) Radical Museology. Or What’s ‘Contemporary’ in Museums of Contemporary Art. London: Koenig Books.

Bourdieu, P. (1980) “Le capital social. Notes provisoires”, In Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 31, 2-3.

Bourdieu, P. (1993) The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bühler, M. (2022) “Introduction: The Art of Critique”, In M. Bühler (Ed.) The Art of Critique, pp. 24-34. Milan: Lenz Press.

Cartagena, M.F. (2017) “Liberation Aesthetics: Social Transformation, Decolonization, and Interculturality”, In B. Kelley Jr. & R. Zamorra (Eds.), Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, pp. 69-76. Los Angeles: Otis and Chiacgo: SAIC.

Cauwet, L. (2017) La domesticación del arte. Política y mecenazgo. Barcelona: Incorpore.

Eribon, D. (1980/2006-2008) “Los intelectuales de hoy. Entrevista a Pierre Bourdieu”, In Pierre_bourdieu BLOG. Retrieved from: http://pierre-bourdieu.blogspot.com/2006/06/los-intelectuales-de-hoyentrevista.html

[Accessed May 1, 2025].

Escobar, T. (2015) Las tribulaciones del arte en los tiempos del mercado total. Madrid: Clave Intelectual.

Foucault, M. (2024) “What Is Critique? and “The Culture of the Self”, edited by H.P. Fruchaud, D. Lorenzini, and A.I. Davidson, translated by C. O’Farrell. University of Chicago Press.

Fraga, C.M. (2014) “Antropología compartida”, In C. Lozano (Ed.), Voluntad de la Piedra (exh. cat.), pp. 77-79. Mexico City: Carrillo Gil Museum and BBVA Bancomer.

Fraser, A. (2005) “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” In ArtForum, September 2005, 278-283.

Fraser, A. (2016) De la crítica institucional a la institución de la crítica. Mexico City: Siglo XXI and Barcelona: MACBA.

Freud, S. (1925/1999) “Negation”, In Standard Edition XIX, translated by James Strachey, p. 235–239, London: Hogarth Press.

Garcia Canclini, N. (1979) La Producción Simbólica: Teoría y Método de la Sociología del Arte. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI Editores.

Garcia Canclini, N. (2010) La Sociedad sin Relato. Antropología y Estética de la Inmanencia. Ciudad de México: Katz.

Guattari, F. (1977) Deseo y revolución. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón.

Guerilla Girls. (1998) The Guerilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. London: Penguin Books.

Guerilla Girls. (2003) The Guerilla Girls’ Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes. London: Penguin Books.

Gutiérrez Castañeda D. (2017) “Hacerse de una Narrativa Redentora”, in A. Castillejo (Ed.), La Ilusión de la Justicia Transicional, pp. 321-357. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

Haacke, H. (1975) Framing and Being Framed. Halifax: Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Haacke, H. (1983) “All the Art That’s Fit to Show,” In AA. Bronson & P. Gale (Eds.), Museums by Artists, pp. 149-152. Toronto: Art Metropole.

Haacke, H. (1995) Obra social (exh. cat.). Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies.

Haacke, H. (2009) “Museums, Managers of Consciousness,” In A. Alberro, & B. Stimson (Eds.), Institutional Critique. An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, pp. 276–288. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Haacke, H. (2012) Castles in the Sky (exh. cat.). Madrid: MNCARS.

Hardt, O., & Negri, T. (2009) Commonwealth. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Holmes, B. (2006) “The Artistic Device, or, the Articulation of Collective Speech”, In Ephemera 6(4), 411–432.

Jacoby, R. (2011) El deseo nace del derrumbe. Acciones, conceptos, escritos (exh. cat). Barcelona: La Central.

Keefe, P.R. (2021) Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty. New York: Doubleday.

Kwon, M. (2002) One Place After Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kosuth, J. (2002) Art after Philosophy and after: Collected Writings, 1966–1990. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lippard, L., & Chandler, J. (1968) “The Dematerialization of Art,” In Art International 12, 2, pp.31-36.

Longoni, A. (2017) “Oscar Masotta: vanguardia y revolución en los años sesenta,” In A. Longoni (Ed.), Oscar Masotta. Revolución en el arte, pp. 7-67. Buenos Aires: Mansalva.

Longoni, A., & Mestman, M. (2004) “After Pop, We Dematerialize: Oscar Masotta, Happenings, and Media Art at the Beginnings of Conceptualism,” In I. Katzenstein (Ed.), Listen here now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, pp. 156-172. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

López Cuenca, R. (2019) Keep Reading Giving Rise (exh. cat.). Madrid: MNCARS.

Luna, A. (2025). Interviews by Eva Marxen y David Gutiérrez Castañeda, February 17 and April 25.

Magnat, V. (2022) “(K)new Materialisms: Honouring Indigenous Perspectives”, In Theatre Research in Canada, 43(1), 24-37

Martin, B. (2013) “Immaterial Land”, In E. Barrett, & B. Bolt (Eds.), Carnal Knowledge. Towards a “New Materialism” through the Arts, pp. 185-204. London: I.B. Tauris.

Marxen, E. (2020a) Deinstitutionalizing Art and the Nomadic Museum. New York: Routledge.

Marxen, E. (2020b) “Opposing Epistemological Imperialism”, In FIELD. A Journal of Socially- Engaged Art Criticism, (15). Retrieved from: https://field-journal.com/editorial/opposing-epistemological-imperialism [Accessed May 1, 2025].

Masotta, O. (1969) “Después del Pop: nosotros desmaterializamos”, In O. Masotta, Conciencia y estructura, pp. 218-245. Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez.

McKenzie, Jon. (2000) Perform or Else. From Discipline to Performance. New York: Routledge.

Medina, C. (2016) “La escritura como acto”, In A. Fraser, De la crítica institucional a la institución de la crítica, pp. 7-10. Mexico City: Siglo XXI and Barcelona: MACBA.

Mesquita. A, Carnevale. G, Vindel. J, Expósito, M (2015) Desinventario. Esquirlas de Tucumán Arde en el Archivo de Graciela Carnevale. Santiago de Chile: Ocholibros.

Mignolo, W. (2011) “Museums in the Colonial Horizon of Modernity. Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992),” In J. Harris (Ed.), Globalization and Contemporary Art, pp.71–85. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing.

Mouffe, C. (2012) “Alfredo Jaar: The Artist as Organic Intellectual”, In A. Jaar (Ed.), The Way it is. An Aesthetics of Resistance, pp. 264–281. Berlin: Realismus-Studio of NGBK, New Society for Visual Arts.

Negri, T. (2017) Marx and Foucault. Malden: Polity Press.

Olivé, E. (2024) Filantrocapitalisme. El mercat de la caritat. Manresa: Tigre de Paper.

Peters, T. (2020) Sociología(s) del Arte y Políticas Culturales. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados.

Pinochet Cobos, Carla. (2024) La cultura descentrada: Estudios sobre democracia cultural en Chile y América Latina. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

Piper, A. (2003) Adrian Piper. Desde 1965 [Adrian Piper. Since 1965]. Barcelona: MACBA.

Povinelli, E. (2011) Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Raunig, G. (2004) “The Double Criticism of Parrhesia: Answering the Question “What is a Progressive (Art) Institution”’, In Republicart, 4. Retrieved from: http:// www.republicart.net/disc/institution/raunig04_en.htm [Accessed May 1, 2025].

Raunig, G., & Ray, G. (Eds., 2009) Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique. London: Mayfly.

Ribalta, J. (2004) “Mediation and Construction of Publics. The MACBA Experience”, In Transversal 4. Retrieved from: https://transversal.at/transversal/0504/ribalta/en [Accessed May 1, 2025].

Ribalta, J. (2010) “Experiments in a New Institutionality”, In M.J. Borja-Villel, K. Cabañas, & J. Ribalta (Eds.), Relational Objects. MACBA Collection 2002–2007, pp. 225–265. Barcelona: MACBA.

Rivera Cusicanqui, S. (2019) Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: On Decolonising Practices and Discourses. New York: Polity Press.

Robinson, J. (2002) “Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map”, In International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26(3), 531-554.

Rosler, M. (1998) “Thesis on Defunding”, In G. Kester (Ed.), Art, Activism & Oppositionality. Essays from Afterimage, pp. 94–102. Durham: Duke University Press.

Steyerl, H. (2009) “The Institution of Critique”, In A. Alberro, & B. Stimson (Eds.), Institutional Critique. An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, pp. 486–492. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tassi, N.; Arbona, J.M; Ferrufino, G., & Rodríguez-Carmona, A. (2012) “El desborde económico popular en Bolivia. Comerciantes aymaras en el mundo global”, In Nueva Sociedad, 241, 93-105.

Tassi, N., & Wilson, P. (2020) “Los caminos de la economía popular: circuitos económicos populares y reconfiguraciones regionales”, In Temas Sociales, 47, 10-35.

Virno, P. (1996) Virtuosity and Revolution: The Political Theory of Exodus. University of Minnesota Press.

Yúdice, G. (2002) El Recurso de la Cultura. Usos de la Cultura en la Era Global. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa.