Opposing Epistemological Imperialism

Eva Marxen

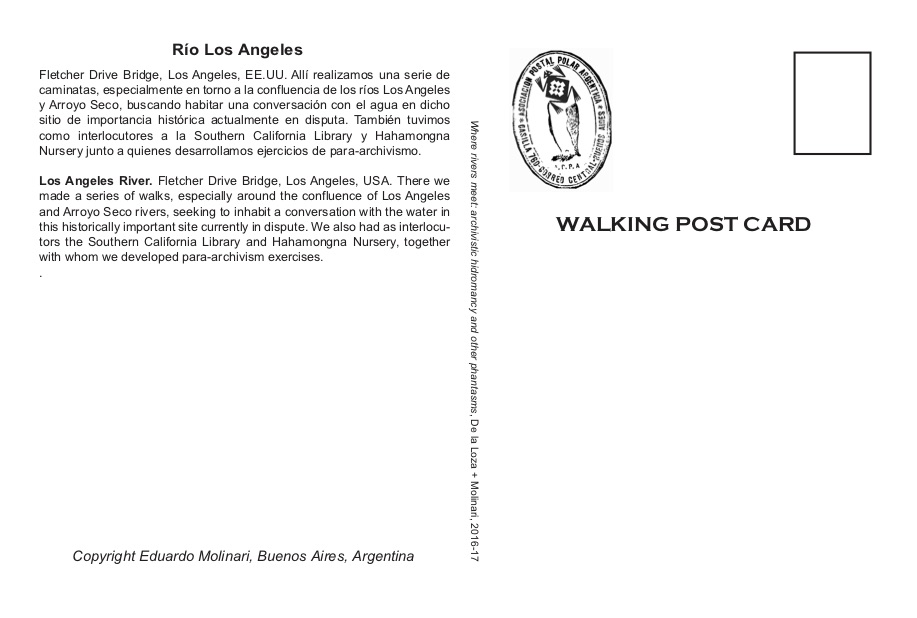

This article focuses on Latin America’s extremely rich heritage of art practices that have taken form as resistance against past and present social, economic, and political oppression. Many artists, art activists and groups have developed and carried out extremely sophisticated artworks, art practices, and artistic interventions based on rigorous critical thinking and guided by principles of collectivity, which have led to highly effective symbolism. As a result of efforts to defy hegemonic discourse, they have been able to successfully oppose society’s mechanisms of control and oppression, creating spaces for resistance and alternative narratives that can eventually lead to social and political change. Recently, many works have been created that successfully oppose environmental pillage and exploitation. For example, the Argentinean duo Iconoclasistas (discussed in the present issue) work with the concept of a rebellious cosmovision. This implies a critical view and a mapping of extractivism, environmental, and neocolonial exploitation, as well as political ecology. Sandra de la Loza and Eduardo Molinari have engaged in transnational research (from Los Angeles and Buenos Aires) about the production of space, extractivist economies, displacement, and both eclipsed and living Indigenous knowledge. The latter has comprehended the importance of a dialogue, and co-existence, with nature and non-humans for hundreds of years, but dominant history has ignored this wisdom.[1]

Examples of Imperialism in the Arts

In South and Central America, local artists have often been predecessors of artistic practices and thoughts that, later, have been touted in North America and Europe as new and innovative, seldom receiving credit for their long-standing contributions. One example would be “the dematerialization of the arts.” In Argentina, Oscar Masotta [2] mentioned the dematerialization of art in the same year as Lucy Lippard, the latter having declared to have been the first.[3] Yet, in 1967, Oscar Masotta gave a lecture at the DiTella Institute (center of the artistic avant-garde in Buenos Aires) titled “Después del pop, nosotros desmaterializamos” or “After Pop art, we dematerialize”. He referred to an article by the Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky, originally published in 1926. Lissitzky advocated for “the integration of artists in the publishing industry through new typography and design. The Russian avant-garde artist was advocating for books as an art form for their expressive possibilities, and their ability to take many forms, noting that ‘dematerialization is the characteristic of the age’” in which the new communication technologies result in the diminishing of physical materiality and the increase of “liberating energy.” Masotta picked up the thread of this concept, considering it in terms of the contemporary artistic processes and forms of communication that sought to dissolve art into social life.[4] I agree with Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman that there is little to be gained by “sterile disputes over the intellectual copyright of a forty-year-old notion.”[5] “The point is rather to think of these coinciding events as a part of the transnational web of the circulation of ideas” rather than focusing on the presumption and marketing entailed in determining which author was the “first” to express them.

In 1998, French curator Nicolas Bourriaud claimed to have introduced the concept of “relational aesthetics.” Yet, artists like Lygia Clark had already worked in the eighties in a much more intense way, establishing relational spaces of subjectivity.[8] In her last phase, from 1976 until her death in 1988, the Brazilian artist developed The Structuring of the Self. This was an art practice that was therapeutic and which fused the boundaries of art and therapy. She treated participants/clients individually, over a pre-determined amount of time, with the help of the “relational objects.” As their name indicates, it is the relationship established with the fantasy of the subject that is important. Clark’s idea was to exorcize through the body the “phantasmatic,” which she located there. She considered the phantasmatic to be the consequence of traumatic experiences that block the creative potential of the human being. It has to be relieved, treated, and transformed in the space of the body, with the help of the relational objects or by means of the direct touch of the artist-therapist’s hands. The relational objects stimulate and mobilize the affective memory because of their texture and the way Clark manipulated and handled them. The physical sensations of these objects were the starting point for a further elaboration of the phantasmatic. People regained their health when they connected with their cuerpo vibrátil (vibratile body), which allowed for a re-connection with their creative power and energy.[9]

The political meaning of her work was extremely important, since Clark herself had witnessed firsthand—and also through her patients’ suffering—the terrible effects of dictatorship and censorship. This terror imposed itself on the Brazilian population’s creative potential, limiting their expression and capacity for symbolization, with obviously detrimental consequences for their mental health. In Donald Winnicott’s terms, in a dictatorship there is no potential space for cultural and creative experience on a macro level.[10] Clark acted as an artist-therapist on the threshold between dictatorship and neo-liberalism in Brazil. The military dictatorships of various Latin-American countries had damaged the potential space of creative experience. Afterwards the newly imposed dynamics of neo-liberalism tried to reanimate artistic activities and expression, but only by using them as an ideological and commercial instrument. Clark had already foreseen a development that, in recent years, has gained significantly in sophistication: the instrumentalization of art through capitalistic dynamics, concretely manifest in the form of the non-profit foundations of multinational companies, which, through the sponsoring of art, culture, social work, etc., accumulate symbolic capital that mainly serves to obscure non-popular capitalistic activities.[11]

In this way, Clark’s artworks can be considered simultaneously as artistic, political, and clinical expressions. She neither wanted to abandon art nor to swap it for clinical practice, “but rather to inhabit the tension of their edges.”[12] Rejecting a perception of art limited to the object-form, she chose to realize artworks in the receiver’s body, so that a person would develop from a passive spectator to an active participant. She searched for an intense relation between art and person, and art and life. Life itself should be an act of art that directly treats social, psychological, political, and corporal spheres.[13] Following this art-life experience as developed by Lygia Clark and also her friend Hélio Oiticica, art was seen to function “as a vehicle for the liberation of the subject, in which they could, through the creative experience, reconstitute their own subjectivity and reconnect art and reality.”[14] Critically, Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics” has been considered “immobilist and regressive in that it ‘aestheticizes’ the immaterial communicative paradigm and its implicit social and creative processes, imposing an expository regime that interrupts their mobility, and freezes and makes fetishes of practices.”[15] The result, according to Jorge Ribalta, is “a perverse objectification of both political activism and the new forms of immaterial, affective, communicative and relational production of post-Fordism.”[16] In other words, it seems “to aestheticize . . . our service economy (‘invitations, casting sessions, meetings, convivial and user-friendly areas, appointments’).”[17] By contrast, Clark went beyond this aestheticization and aimed at a “poetic lived experience” for subjective charge and change.[18] Her Brazilian fellow Oiticica “also felt this necessity of killing the [concept of the] spectator or participator”. He was strictly against unbearable “dull experiences” or “facile participation”. Together with Lygia Clark, they aspired to annul the subject-object relationship, in favor of “an interpersonal practice that leads towards a truly open communication: a me-you relation . . . ; no corrupted benefit . . . should be expected.”[19] Few artists and thinkers of the South have ever been given any credit for their highly relevant previous works. Over the past few decades, community-based art and socially engaged art have both rapidly spread through North American art practice and academia. In alignment with the Talking to Action show, the intellectual, methodological, cultural, and political roots of these practices have been revived in Latin America, the objective being to “redirect the legacies of the past” by an “alternate mapping.”[20]

The Political and Colonial Economy of Knowledge

Differing forms of epistemological imperialism are evident in the global political economy of knowledge, capitalist subjectification, as well as co-option of knowledge and alternative practices. Artists have been able to express and denounce the forms of epistemological imperialism embedded in this oppressive global political economy for many years. This system was initiated at least half a century ago by, among other institutions, the University of Chicago in the form of grants for the so-called “Chicago Boys,” Chilean students of economist Milton Friedman who would study neoliberalism firsthand in order to implement it in their home country, leading to atrocious violations of human rights. Especially interesting in this regard are the following films about the Chicago Boys: The Battle of Chile I-III (1976-98) by Patricio Guzman; The Conspiracy (2006; original title: Héros fragiles: Chile 1973. Affaire non classée) by Emilio Pacull; Chicago Boys (2015) by Carola Fuentes & Rafael Valdeavellano, and Juan Downey’s eponymous video from 1983. They all show how military and state violence was an accepted means to the end of expanding neoliberalism from North to South. Nowadays in Chile [21], the most persistent, creative, and enduring protests have been organized to change profoundly or to abolish entirely this same neoliberalist system.

Neoliberalism was cruelly implemented and propagandized as a form of progress, modernization, and development. Latin American authors have played a leading role in the analysis of the concept of “coloniality,” articulated by Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano, [22] and defined by Walter Mignolo [23] as concerned with opening up “the reconstruction and the restitution of histories, subjectivities, knowledges, and languages silenced, repressed, and subalternized by the Totality depicted under the names of modernity and rationality.”[24] In return, the Coloniality/Decoloniality framework offers theoretical and cultural “strategies of resistance to a modernity that perpetuates the colonial condition.” This “decolonial option of delinking, [has] mostly [appeared] in the form of what has been described as epistemic disobedience and border thinking.”[25] In her article “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985” (part of an eponymous exhibition and catalogue), curator Julieta González correctly points out that “this kind of reflection in the cultural field is not the exclusive province of the Modernity/Coloniality/Decoloniality group.”[26] From Paulo Freire and Ivan Illich’s ideas on conscientization and de-schooling in the 1960s and ‘70s, to Enrique Dussel’s Philosophy of Liberation [27] or Néstor García Canclini’s Hybrid Cultures, [28] we find a range of thinkers proposing “strategies to enter and exit modernity; more recently, many theorists have argued in favor of the epistemologies of the South, as ones that ‘adequately account for the realities of the Global South’.”[29] And even before, or simultaneous with, many of the aforementioned writers and academics, similar ideas “had been anticipated in the fields of visual arts, architecture, and film, across Latin America, beginning in the early 1960s.” The objective of the Memories of Underdevelopment show, produced at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, has precisely been “to identify and map these early instances of a decolonial turn in art and culture as an important part of this history.”[30]

Epistemologies of the South

More recently, thinkers such as Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui [31] or Boaventura de Sousa Santos’s have focused on the “epistemicide” [32] committed by “cognitive empire,” and called for de-totalizing and decolonizing practices to challenge it. For Santos, these practices must go hand in hand with transformative thinking.[33] It starts with questioning epistemological foundations and the way of thinking itself: “We don’t need alternatives; we need rather an alternative thinking of alternatives,” as Santos argues.[34] In Santos’ book The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, one of the main objectives of the epistemologies of the South are described in terms of the effort by “oppressed social groups [to] represent the world in their own terms, to change it according to their own aspirations,” in order to challenge the discourses of development and a form of “modernity that perpetuates the colonial condition.”[35] By contrast, the epistemologies of the North “have contributed to converting scientific knowledge developed in the global North into the hegemonic way of representing the world as one’s own, and of transforming it according to one’s own needs and aspirations. In this way, scientific knowledge, combined with superior economic and military power, granted the global North the imperial domination of the world in the modern era up to our days.”[36] Thus, the epistemologies of the North reproduce capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy, as well as the oppression and repression caused by this imperialist triad. They conceive their Eurocentric epistemologies “as the only source of valid knowledge” in a scenario in which the North is the solution and the South is the problem. For centuries the North has failed to consider vast bodies of knowledge as valid which has led to a massive epistemicide, a massive “destruction of an immense variety of knowing,” and consequently to a disempowerment of entire societies.[37]

Yet, while resisting and opposing epistemicide, the goal of the epistemologies of the South does not consist in simply replacing one hegemony with another, like putting the epistemologies of the South in the place of their dominant, Northern counterparts. The South, rather, rebels “to overcome the existing normative dualism” and aims at overcoming “the hierarchical dichotomy between North and South” by erasing “the power hierarchies inhabiting them.”[38] “The epistemologies of the South are not the symmetrical opposite of the epistemologies of the North, in the sense of opposing one single valid knowledge against another.”[39] Furthermore, the notion of South is non-geographical and anti-imperial. It is related to both historical colonialism and internal colonialism. That is the reason why it can be applied simultaneously to the geographical North and the South.

Santos proposes a sociology of absence and a sociology of emergence. The first consists in retrieving the epistemologies of the South and converting them from absent into existing: redeeming them is seen as an “eminently political gesture.”[40] The sociology is described as “the cartography of the abyssal line. It identifies the ways and means through which the abyssal line produces nonexistence, radical invisibility and irrelevance . . . the colonialism of power, knowledge, and being, operates together with capitalism and patriarchy to produce abyssal exclusions, that is, to produce certain groups of people and forms of social life as nonexistent, invisible, radically inferior, or radically dangerous—in sum, as discardable or threatening.”[41] And worse: Any knowledge susceptible of subverting the capitalist, patriarchal, colonial order has been violently suppressed. “Knowledge as regulation ended up cannibalizing knowledge as emancipation.”[42] This is reflected in the current phase of neoliberalism in the form of the ever-growing dependence and cooption of the scientific community by extra-scientific capitalist entities. The latter determine the political economy of ideas and monopolize the ecologies and plurality of knowledges.[43] In general, “given the capitalist impulse for commodifying scientific knowledge and thus for reducing the value of scientific knowledge to its market value, and with the consequent subjection of research in universities and research centers to criteria of short-term profit, scientific pluralism may fade away, particularly in those areas that have become coveted fields for capital accumulation.”[44]

The sociology of emergences deals with the “symbolic, analytical, and political valorization of the ways of being and knowing . . . on the other side of the abyssal line.”[45] It aims at an ecology and repertoire of knowledge that recognizes and gives space to different ways of knowing. Affinities, divergences, complementariness and contradictions are focused in order “to maximize the struggles of resistance against oppression.”[46] Although the epistemologies of the South “take for granted that neither modern science nor any other way of knowledges captures the inexhaustible experience and diversity of the world,”[47] they foster the combination of contemporary science with Indigenous knowledge whenever it can help Indigenous struggle. This is the case in peasant agriculture and its fights against capitalist as well as colonialist extractivism.[48] Moreover, the sociology of emergence conceives “liberated zones, spaces that organize themselves according to principles and rules radically opposed to those that prevail in capitalist, colonialist, and patriarchal societies . . . Their purpose is to bring about . . . a different kind of society . . . liberated from the forms of domination prevailing today.”[49] These spaces offer “alternative ways of building collectives,” combining social experience with social experimentation, often of performative nature. A number of artists have worked precisely in this vein. They have created spaces of experimentation, in opposition to capitalism, facilitating a form of experimentation with utopia and subjectivity as an alternative to the normalization of life styles. In their work, new ways of inhabiting the world are evidenced, deconstructing institutionalized models and points of view.[50] The possibility of change through agency is transmitted mainly through images.[51] At the same time, a critical analysis is undertaken by questioning hegemony, in Gramscian terms.[52] The aforementioned Lygia Clark, with her ongoing artwork Structuring of a Self, is a very good example. Some other heterogeneous representatives of this art form are the Venezuelan artist Gego, who created, on a more abstract level, geometrical and architectural sculptures, defying the laws of gravity [53] or Argentinean Roberto Jacoby with his technologies of friendship, his experimental communities and micro-societies, such as Proyecto Venus (2001-2006).[54]

One of the main characteristics of the epistemologies of the South is the fact that their production and validation is “anchored in the experiences of resistances of … social groups that have systemically suffered injustices, oppression, and destruction caused by capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy.”[55] They arise from knowledge gained through “social and political struggles and cannot be separated from these struggles.” By contrast, “in Eurocentric social theory, Marxism excluded, the topic of social struggle and resistance has always been treated as a mere subtopic of the social question, the privileged focus being on social order rather than on social conflict.” In agreement with Santos, struggles always circulate around questions of limits and freedom.[56] He further distinguishes hegemonic and counter-hegemonic freedom. The former is “authorized by whoever has the power to define its limits . . . On the contrary, counterhegemonic freedom is autonomous and emancipatory. It acknowledges the force but not the legitimacy of limits, and so acts toward displacing them, putting maximum pressure on them in order to overcome them whenever possible.”[57]

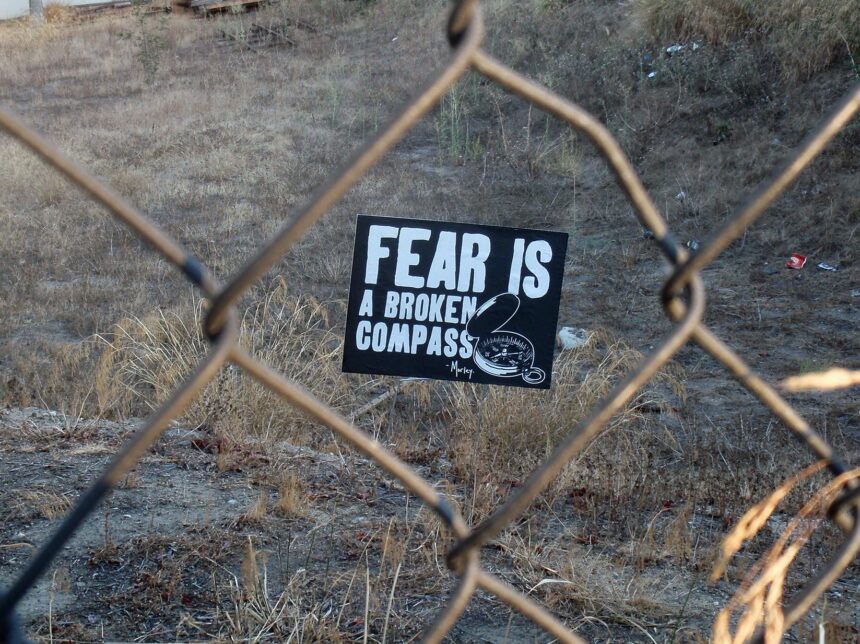

The epistemologies of the South intend to decolonize social science by nonextractivist methodologies, “grounded on subject-subject relations rather than subject-object relations.”[58] They oppose the abyssal social sciences and their methodologies, which “extract information from research objects in very much the same way as mining industries extract minerals and oil from nature.” By contrast, Southern epistemologies strive for “knowing with” instead of “knowing about” aiming at a co-construction of meaning which is circulate rather than linear. Additionally, they are based on artisanship. They refuse standardized methods and mechanical construction, the same way an “artisan never produces two pieces exactly alike.”[59] Furthermore, the epistemologies of the South rely on the experiences of the senses as a source of knowledge, a source denied by the North. The latter exclusively considers reason as the only vehicle of valid knowledge. The Southern construction of knowledge is at “the antipodes of such a stance.”[60] In Argentina, a resistance strategy reliant on the senses had been conceived mainly by Roberto Jacoby as the Strategy of Joy, Estrategia de la alegría. During the eighties, this ongoing, eponymous artwork meant to oppose the most difficult situations of loss and suffering during the military dictatorship by organizing underground punk music and dance events. People would gather in spaces, forbidden by the military rules, to live collectivity, the experience of their bodies moving together with pleasure, challenging the military’s perverse discipline, moralist impositions, and total fragmentation of social life. In contrast, participants celebrated “the exultation of being alive, of enjoying our bodies, and of transforming them by disobeying disciplinary norms.”[61] The contestation of “superabundance of fear” and sadness is a form of resistance against capitalism, since fear and sadness instrumentalize people’s lives in a direction of enchained subjectivities.[62]

Another main inquiry of Southern epistemologies is the de-monumentalization of written knowledge in favor of oral knowledge. Written knowledge is static and hence monumental, difficult to “engage in dialogue or conversation with other knowledges.”[63] Yet, the epistemologies of the South are based in dialogue, the co-construction of meaning, and the formation of alliances. They aim at counter-hegemonic publics [64] and foster popular education. This also implies the “liberation from academic colonialism” [65], for example with the integration of Indigenous knowledge into the academic curriculum.[66] In a time where the environment is seriously threatened on all continents, Indigenous knowledge can show people a different relationship to it based on mutual respect.[67] Critically, the Northern university must be decolonized. Since its very foundation, the knowledge circulating in it, has never been universal but Western from its very beginning. It has always served as the cradle and “nursing home” of Northern epistemologies.[68] Here, the challenge lies in how to decolonize knowledge in an institution that produces it. A counter-hegemonic use of archives is necessary, as outlined by Sandra de la Loza, Eduardo Molinari, and Josh Rios as well as the Red Conceptualismos del Sur in this issue. The latter network pursuits political interventions that oppose the commodification and neutralization of the critical potential manifest in many political-conceptual practices in Latin America.[69] The deconstruction of archives broadens and alters the possibilities of sources beyond, or besides, the official discourse. This is crucial for decolonization because the very choice of sources always has theoretical and political implications.[70]

The authorship of Northern epistemologies is anchored in individualism, as opposed to the aforementioned alliances. These epistemological forms are rooted in individualistic, fragmented, possessive societies. By distinction, Southern knowledge that emerges from social struggle is, from its very inception, collective and operates as such. It clashes with the rules of academic evaluations that are centered in authorial individualism. Furthermore, Southern academic knowledge has nurtured itself with a multitude of ideas that have come from abroad whether in form of books and articles that many scholars from the South read in their original languages, or in form of academic studies on different continents. At the same time, these knowledges have been modified, intervened, decolonized, and enriched. “Heterodoxy has always been feature of our cultural doing,” according to Silvia Cusicanqui, a kind of “baroque ethos.”[71] This heterodoxy, together with complex and multiple realities, freed Southern academics from linguistic provincialism and the orthodoxy and dogmatism of schools of thought. The final goal of the transformation of society towards justice is incompatible with provincialism.[72] As such, Southern epistemologies include the oral circulation of knowledge as opposed to the exclusivity of written forms. This is linked to the importance that “orality and oral culture play in social struggle.”[73] The oral includes deep listening. It is transmitted in a collectivity and includes visual, sound as well performative aspects. As Sousa Santos argues, “the borderline between art and oral knowledge is often difficult to establish.”[74]

I would offer the Taller de Historia Oral Andina [Workshop of Andean Oral History] in La Paz, Bolivia as an example. Mainly driven by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, their objectives rely on re-building the History of Indigenous peoples in the Andes region. They tell their story themselves and their discourse shows, according to Sousa Santos, “their worldviews and ways of life, their views on their struggles throughout the centuries, their heroes, and their aspirations concerning justice, dignity, and self-determination.” The knowledge circulates in communities, through publications and public debates. At the same time, it critiques the epistemologies of the North and serves as a source, an alternative archive, “at the service of many Indigenous organizations that have taken advantage of it to strengthen their own struggle against capitalism and colonialism.”[75] Other examples are the Pedagogy of the Oppressed as outlined by, among others, Paolo Freire, or Participatory Action Research as developed by Fals Borda.[76] In the Northern appropriation of Freire his identification with the excluded is often decontextualized from his acknowledgment of underdevelopment and the aforementioned opposition against the rhetoric of development (desarrollismo), progress, and modernization.[77] At the same time, the Pedagogy of the Oppressed is frequently reduced to Freire as the lone representative. However, movements and ideas related to the Pedagogy of the Oppressed have spread through various Latin American countries, such as Mexico (still today prominent at the Institute for Critical Pedagogy at Chihuahua [78]), Peru, Columbia, and Chile. In the latter country, it was very much fostered during the government of Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity alliance. Among many cultural and educational movements, the Museum Solidarity Salvador Allende (MSSA) should be emphasized. The museum was, from its very beginning in 1971, in an organic relationship with the revolutionary process of the country, especially since cultural and revolutionary battles were organically interwoven and inseparable: “In its essence, the struggle for socialism is the struggle for culture.”[79] The museum collection should reflect art as a collective necessity and account for artistic solidarity in a specific historical moment. This sense of solidarity continued throughout the dramatic history of the museum. It was brutally interrupted by the military coup (1973) and during the subsequent regime (1973-1990), the museum was forced into exile. There, the solidarity of artists made its survival possible as a nomadic museum.[80] Nowadays, the museum continues its collections, exhibitions, and especially its public programming in the same spirit, the latter very much orientated towards its popular neighborhood.[81]

Another relevant issue that must be addressed is the way in which Northern thinking engages with that of Southern epistemologies. When the epistemologies of the South are recognized, they suffer banalization and simplification, especially when taken out of their geopolitical context. Cusicanqui has found very clear words in her critique against academics of the North who only see “the top of the iceberg when an intense and prolonged experience has taken shape in written form. [Then] it transitions to the market of ideas where cooperative interests and cliques proliferate”.[82] The decontextualization inevitably leads to the imposition of Northern views and ideologies on the Southern elaboration.

Cusicanqui’s work with the Taller de Historia Oral Andina (THOA) is defined by her focus on oral knowledge and her expertise in the Sociology of Images. Both the oral and the visual serve to oppose colonialism and its written monumentalization in favor of a reconnection “with the profound rivers of the anti-colonial vitality.”[83] The oral and the visual help to express alternative conceptions of the world and epistemes. They are also able to decolonize the Cartesian oculocentrism and to redirect and deconstruct the gaze towards what has been repressed in the official discourse of History. They can excavate traumas of the past, produced by colonial violence and state repression, retrieving the erased parts of history. Although Foucault did not write extensively on issues related to colonialism, he did analyze the hierarchical gaze. Those in the superior position of domination exercise the power of naming and representing the real. Thus they control the dominated. For Foucault, the first gesture of resistance is to lift one’s head and hence one’s gaze.[84] Both orally transmitted knowledge and images reconnect us with the conflicts and crises of the past and thus help us to understand the present. Cusicanqui refers to Walter Benjamin, and his concept of the “dialectical image” seems relevant to her work.[85] For Benjamin, dialectical images are able to evoke both the past and the present, and can be understood as marking the unexpected memory of a redeemed humanity.[86] A critical part of the past is unleashed in the present. These images untangle past repressions and at the same time offer us new possibilities for the present. The shock provoked by the dialectical image helps us to understand present conditions in order to change them. For Benjamin, the artist’s and intellectual’s task is to operate with and through the dialectical image. New constellations are created by collage, film, montage, and rearrangement. They imply “a Marxist project of bringing events together in new ways, disrupting established taxonomies, disciplines, mediums, and properties.”[87] Yet, Cusicanqui does not follow the dialectical path. Her sociology of images is based on the epistemology ch’ixi, geographically located in the regions of the Aymara people: the shores of Lake Titicaca, the Bolivian altiplano, the North of Chile and Northwestern Argentina. Ch’ixi consists of knowledges composed of contradictions, paradoxes, and the hidden and forgotten.[88] The Aymara language itself is polysemic. As opposed to Western concepts of dialectics, syncretism or hybridity, ch’ixi is not a mere transitory state that has to be overcome (like in dialectics) by a third revealing and relieving element. It is in itself an explosive force that maximizes our capacity for thought and action, opening a third space where alleged opposites come together in a dynamic way, enriching and contesting each other without ever hybridizing or fusing. Ch’ixi offers a space for complementary opposites, to think about the desired and the rejected, following the energy of desire.[89]

With orality, along with the production of new images and the re-reading of existing images, a decolonizing practice is constituted that is able to retrieve repressed memories. These practices are communicative and give space to a multiplicity of people and collectives for their alternative Histories to emerge with a plurality of meanings. Proliferating discourses unfold in various directions and are not collapsed into a linear, one-dimensional determination. Photography, cinema, the long lasting Andean traditions of social theater, paintings and textiles “express moments and segments of a non-conquered past that have remained rebellious against the integrating and totalizing discourse of social science and its great narratives . . . Instead of seeing in them [images] only a source of support that merely illustrate the more general interpretations of society . . . they are rather hermeneutic pieces of and by themselves.”[90] The resulting images can surpass the verbally established meaning beyond one single and determining signifier by opening up new meanings and possibilities.[91] At the same time, they can show the fractures of normative discourses and how the world is as opposed to how it should be.[92] Cusicanqui aims at deciphering the contemporary bombardment of images as exercised through social media, publicity, etc. The colonizing intentions beyond the image itself and its massive proliferation must be revealed. Rather than being merely exotic or decorative, the images and the processes necessary to produce, distribute and read them constitute a practical critique of colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchy, with all their accompanying exploitation. Indigenous knowledge developed this critique even before these concepts were elaborated by social science. The latter used to erase the voices of the subaltern and followed a linear and evolutionist vision of history, according to a Eurocentric rationality. In this sense, Indigenous societies have been seen as remote from the market, static and retarded, relying on irrational traditions and far away from any concept of progress. Cusicanqui’s analysis of hegemony and subalterity coincides with Italian Marxist anthropology based on the work of Ernesto de Martino.[93] His inquiry aimed at re-historicizing subaltern culture, giving it a place of contestation against hegemony and colonialism. Far from equating the subaltern with superstition, the primitive or the retarded, he considered it an active, creative form of resistance.

Unfortunately, subaltern cultures have suffered a nostalgic and consumerist recuperation in the form of a capitalist recycling and co-option of the folklore of the same societies that the imperial capitalist system had previously sought to eradicate.[94] In opposition, the THOA has successfully shown the active role Indigenous societies played in society and in market circuits through the centuries with their own ways of anarchist organization and guilds formation. The immediacy of images and allegories, their composition and assemblage contribute to the interpretation of the past, contesting its vision as something given. Instead, a vision of a past-present-future is offered, as a source of renovation and critique against oppression and domination caused by the violent imposition of progress and modernization.[95] In this manner the de-historized past of the subaltern is re-historized.[96] We can perceive the traces of the past as a force that becomes manifest in “moments of danger” (Walter Benjamin) or through “the crisis of presence” as outlined by de Martino. The latter describes the risk of losing the relation of oneself with the world, of feeling annulled by a situation, with no control over the forces of cultural and social oppression employed by society’s elites. Faced with the risk of disintegration, it is essential to create an alive past that resists the “homogenizing of Eurocentric modernization.”[97] The past is rewritten by the actions of the present, which help to confront the predicaments of the here and now. Understanding the past also means envisioning a future that differs from the present. Cusicanqui’s sociology of images has crossed the frontiers between art and social science. It implies a “transdisciplinary focus that allows to explore the contradictions and biases of modernization, including its . . . fragmenting nature.”[98] This risky and abysmal knowledge challenges, surpasses, and goes beyond the written. In order to de-monumentalize and decolonize hegemonic knowledge, we need new instruments, as well as new practices. We need new knowledge or a new practice of knowledge, and innovative methodologies.[99] “Nobody has yet made a successful revolution without a revolutionary theory,” according to Santos.[100] Following Oscar Masotta, the theoretical dimension should be considered “a specific mode of emancipatory political intervention.”[101] Opposing the sole focus on “practice” in many socially engaged art circles, I insist with Masotta on “the political condition of the exercise of thinking”[102] to bring about an epistemological shift in art and society.

Eva Marxen is an anthropologist (PhD and DEA), art therapist (MA), and psychoanalytical psychotherapist (MA). Currently, she works as an assistant Professor, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. For a decade, Marxen worked with the MACBA (Museum of Contemporary Art) and at the art school La Massana (UAB), both in Barcelona, Catalonia/Spain. She has published numerous articles in both books and journals in different languages and has held conferences as well as workshops at a national and international level. Moreover, she has guest lectured at the art faculties of the University of Chile and the University Finis Terrae (Santiago de Chile), the Universities of Genoa (Italy), Toulouse (France), Veracruz, the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) Xochimilco (both in Mexico), the National University of Córdoba and the Center of Psychotherapy Studies (CEP, both in Argentina) as well as the Institute of Music, Art and Process (IMAP, Basque Country/Spain). Additionally, she has been an invited researcher at the University of the Philippines Diliman, Manila. In 2011, Marxen published the book Dialogues between Art and Therapy: From “Psychotic Art” to the Development of Art Therapy and its Applications (Gedisa, Barcelona). Her next book Deinstitutionalizing Art of the Nomadic Museum will be published in 2020 by Routledge New York.

Notes

[1] De la Loza, Molinari, & Rios in the present issue.

[2] Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, “After Pop, We Dematerialize: Oscar Masotta, Happenings, and Media Art at the Beginnings of Conceptualism,” in Listen here now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, edited by Ines Katzenstein (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), pp.156-172.

[3] Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” Art International 12, no. 2 (1968), pp.31-36; Ana Longoni, “Oscar Masotta: vanguardia y revolución en los años sesenta,” in Oscar Masotta. Revolución en el arte, edited by Ana Longoni (Buenos Aires: Mansalva, 2017), pp.7-67; Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, “After Pop, We Dematerialize: Oscar Masotta, Happenings, and Media Art at the Beginnings of Conceptualism,” p.157. See for the written version of Masotta’s lecture “Después del Pop: nosotros desmaterializamos”, in Conciencia y estructura (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1969), pp. 218-245.

[4] Ana Longoni, “Masotta and his specters,” in Oscar Masotta. Theory as action (Mexico City: MUAC, UNAM, 2017), exhibition catalogue, pp.24-36.

[5] Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, “After Pop, We Dematerialize: Oscar Masotta, Happenings, and Media Art at the Beginnings of Conceptualism,” p.158.

[6] Ana Longoni, “Oscar Masotta: vanguardia y revolución en los años sesenta,” p.19, translated by myself from Spanish.

[7] Ana Longoni, “Oscar Masotta: vanguardia y revolución en los años sesenta.”

[8] Lygia Clark, edited by Manuel Borja and Nuria Enguita (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 1998), exhibition catalogue; Lygia Clark. The Abandonment of Art, 1948-1988 edited by Cornelia Butler and Luis Pérez-Oramas (New York: The Museum of Modern Art), exhibition catalogue; Eva Marxen, “Therapeutic Thinking in Contemporary Art. Psychotherapy in the Arts,” The Arts in Psychotherapy 36 (2008), pp.131-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.10.004; Suely Rolnik, Lygia Clark: De l’œuvre à l’événement–Nous sommes le moule. A vous de donner le soufflé (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, 2005), exhibition catalogue.

[9] Suely Rolnik, “The Hybrid of Lygia Clark,” in Lygia Clark, edited by Manuel Borja and Nuria Enguita (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies), exhibition catalogue, pp.341–348; Suely Rolnik, Lygia Clark : De l’œuvre à l’événement–Nous sommes le moule. A vous de donner le soufflé.

[10] Donald W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1971).

[11] Pierre Bourdieu and Hans Haacke, Free Exchange, translated by Randal Johnson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994); Eva Marxen, “Therapeutic Thinking in Contemporary Art. Psychotherapy in the Arts;” Eva Marxen, “Artistic Practices and the Artistic Dispositif. A Critical Review,” Antípoda. Journal of Anthropology and Archeology 33 (2018), pp.37-60; Eva Marxen, “Transforming Traditions: Walter Benjamin, Art, and Art Therapy,” in Traditions in Transition: New Articulations in the Arts Therapies, edited by Richard Hougham, Salvatore Pitruzzella, and Hilda Wengrower (London: Ecarte, 2019), pp.251-271.

[12] Suely Rolnik, “The Hybrid of Lygia Clark,” pp.347-348.

[13] Suely Rolnik, Lygia Clark. De l’œuvre à l’événement—Nous sommes le moule. A vous de donner le soufflé; Lula Wanderley, O dragão pousou no espaço. Arte contemporânea, sofrimento psíquico e o objeto relacional de Lygia Clark (Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Rocco, 2002).

[14] Rina Carvajal, “The Experimental Exercise of Freedom,” in The Experimental Exercise of Freedom: Lygia Clark, Gego, Mathias Goeritz, Hélio Oiticica, and Mira Schendel, edited by Susan Martin and Alma Ruiz (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999), exhibition catalogue, p.51.

[15] Jorge Ribalta, “Experiments in a New Institutionality,” in Relational Objects. MACBA Collection 2002-2007, edited by Manuel Borja, Kaira Cabañas and Jorge Ribalta (Barcelona: MACBA, 2010), p. 252.

[16] Ibid., p.251.

[17] Hal Foster, “Chat Rooms,” in Participation, edited by Claire Bishop (London: Whitechapel Gallery and Cambridge: MIT Press), p.195.

[18] Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, “Letters,” in Participation, edited by Claire Bishop (London: Whitechapel Gallery and Cambridge: MIT Press), p.110.

[19] Hélio Oiticica, “Dance in my Experience,” in Participation, edited by Claire Bishop (London: Whitechapel Gallery and Cambridge: MIT Press), p.111, 115.

[20] Bill Kelley, Jr., “Talking to Action: A Curatorial Experiment Towards Dialogue and Learning,” In Talking to Action. Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, edited by Bill Kelley Jr. with Rebecca Zamora (Los Angeles: Otis College and Chicago: School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), p.7.

[21] See the relevant contributions by Varas, Ramírez, Rivera-Aguilera and Jiménez in this issue.

[22] Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” Nepentla: Views from the South 1(3) (2000), pp.533–580.

[23] Walter Mignolo, “Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-coloniality, Cultural Studies 21(2) (2007), 449-514.

[24] Ibid., p. 451. See also the critique against the “coloniality group” by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2015) and Aura Cumes, “Notas sobre el racismo académico,” http://tujaal.org/racismo-academico/ (2018) and “Genocidio y memoria,” http://tujaal.org/genocidio-y-memoria/ (2018), accessed January 24, 2020, as both feminist scholars show how the group has omitted the dynamics of internal colonization.

[25] Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985,” in Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985, (San Diego: Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, 2018), exhibition catalogue, pp.26-27.

[26] Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985,” p.27.

[27] Enrique Dussel, Philosophy of Liberation (Portland: Wipf & Stock Publisher, 2003).

[28] Néstor García Canclini, Hybrid Cultures (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

[29] Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985,” p.27.

[30] See additionally Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South (Durham and London: Duke, 2018), and Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina.

[31] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Ch’ixinakax utxiwa. Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores (Valparaiso: Editorial La Xampurria, 2010); Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Un mundo ch’ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2018).

[32] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South.

[33] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.viii.

[34] See also de la Loza, Molinari, & Rios in this issue.

[35] Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985,” pp.26-27.

[36] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.6.

[37] Ibid., p.8.

[38] Ibid., p.7.

[39] Ibid., p.x.

[40] Ibid., p.3.

[41] Ibid., p.25.

[42] Ibid., p.42.

[43] Ibid.; Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina.

[44] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, pp. 46-47.

[45] Ibid., p.28.

[46] Ibid., p.8.

[47] Ibid., p.45.

[48] See the work of Iconoclasistas and de la Loza & Molinari in this issue.

[49] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.31.

[50] Ana Longoni, “Experimentos en las inmediaciones del arte y la política,” in Roberto Jacoby. El deseo nace del derrumbe. Acciones, conceptos, escritos, edited by Roberto Jacoby (Barcelona: La Central, 2011), pp.5-29.

[51] Eva Marxen, “Pain and Knowledge: Artistic Expression and the Transformation of Pain,” The Arts in Psychotherapy 38 (2011), 239–246. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.07.003.

[52] Eva Marxen, “La expresión veraz de los saberes corporeizados,” in Más allá del texto. Cultura digital y nuevas epistemologías, edited by Ileana A. Hernández, Luisa F. Grijalva Maza, and Alfonso A. R. Gómez Rossi (Mexico City: Editorial Itaca, 2016), pp.67-78; Eva Marxen, “Artistic Practices and the Artistic Dispositif. A Critical Review.”

[53] Yve-Alain Bois, Mónica Amor, Guy Brett and Iris Peruga, Gego: Defying Structures, exhibition catalogue (Barcelona: MACBA, 2006).

[54] Roberto Jacoby, Roberto Jacoby. El deseo nace del derrumbe. Acciones, conceptos, escritos, edited by Roberto Jacoby (Barcelona: La Central, 2011).

[55] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, pp.1-2,63.

[56] Ibid., pp.65-66.

[57] Santos (ibid.) heavily critiques NGOs and their false dynamics of helping in struggles while also abusing their position of hegemonic autonomy.

[58] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, pp.x,14-15.

[59] Ibid, p.35.

[60] Ibid, p.15. See in this context Paul Preciado’s focus on sexual subjectivity. He argues that critical theory of the twentieth and twenty first centuries “stopped biopolitically at the belt” (Paul Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, (New York: The Feminist Press, 2013), p.37. They preferred to stress cognition, language, and the symbolic. “Absent from such theory is the material—the work of material substances, in particular—on how subjects came to be” (Eva Marxen and Adam Greteman, “Ingesting Power,” RECIE. Electronic Cientific Review of Educational Research, vol. 4, no. 2. (2019), p.877).

[61] Ana Longoni, 34 Exercises of Freedom: #9 Between Terror and Revelry. Collective Strategies of Resistance during Dictatorships in Argentina and Brazil. Retrieved from: https://www.documenta14.de/en/calendar/969/-9-between-terror-and-revelry-collective-strategies-of-resistance-during-dictatorships-in-argentina-and-brazil [Accessed January 24, 2020]; Red Conceptualismos Sur, Perder la forma humana. Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Madrid: MNCARS, 2012); Roberto Jacoby, Roberto Jacoby. El deseo nace del derrumbe. Acciones, conceptos, escritos.

[62] Reinaldo Laddaga, “Interview with Roberto Jacoby,” The BAR. Buenos Aires Review. Retrieved from: http://www.buenosairesreview.org/2013/11/interview-with-roberto-jacoby/ [Accessed January 24, 2020].

[63] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.15.

[64] See Jorge Ribalta, “Experiments in a New Institutionality;” Eva Marxen, “Therapeutic Thinking in Contemporary Art. Psychotherapy in the Arts;” “La expresión veraz de los saberes corporeizados;” “Artistic Practices and the Artistic Dispositif. A Critical Review” about the efforts of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona to bring art into the social arena.

[65] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.47; Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina.

[66] A successful example here would be the Intercultural University of Veracruz (UVI) and their efforts to include and foster Indigenous knowledge and languages. https://www.uv.mx/uvi/mision-vision-y-objetivos/ [Accessed February 3, 2020].

[67] See de la Loza, Molinari, and Rios in this issue.

[68] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.xi.

[69] Dora García, “Cómo se repitió a Masotta”, in Segunda Vez que siempre es la primera, edited by Dora García (Madrid: MNCARS, 2018), exhibition catalogue, pp.144-161.

[70] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South; the entire issue of Learning Art and Resistance.

[71] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina, p.308, translated by myself from Spanish.

[72] See above Longoni about the interconnection of diverse theoretical bodies in Buenos Aires.

[73] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.61.

[74] Ibid., p.57.

[75] Ibid., p.59; Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Un mundo ch’ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis.

[76] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South; Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, translated by Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum, 1970); Paulo Freire, The Politics of Education: Culture, Power and Liberation, translated by Donaldo Macedo (South Hadley: Bergin and Garvey); Orlando Fals-Borda and Luis Mora-Osejo, “Beyond Eurocentrism: Systematic Knowledge in a Tropical Context. A Manifesto,” in Cognitive Justice in a Global World: Prudent Knowledges for a Decent Life, edited by Boaventura de Sousa Santos (London, Lexington Books, 2007), pp.21–38; Orlando Fals-Borda and Mohammad Anisur Rahman, Action and Knowledge: Breaking the Monopoly With Participatory Action Research (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1991).

[77] Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985.”

[78] http://ipec.edu.mx/ [Accessed February 3, 2020].

[79] Mário Pedrosa, De la naturaleza afectiva de la forma (Madrid: MNCARS, 2017), p.134.

[80] MSSA—Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende 1975-1990 (Santiago de Chile: MSSA, 2016).

[81] http://mssa.cl/the-museum-2/; Soledad García Saavedra, “Co-creaciones barriales: transformaciones recientes del Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende y el barrio república en Santiago, una experiencia de descentralización museal,” Revista de Gestión Cultural 10 (2017), pp.26-29.

[82] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina, p.306.

[83] Tinta Limón, “Palabras previas,” in Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón), p.8, translated by myself from Spanish.

[84] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Random House, 1975).

[85] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina.

[86] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, edited by Rolf Tiedemann, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (New York: Belknap Press, 2002).

[87] Claire Bishop, Radical Museology. Or What’s ‘Contemporary’ in Museums of Contemporary Art (London: Koenig Books, 2013), p.56.

[88] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Un mundo ch’ixi es posible. Ensayos desde un presente en crisis.

[89] In psychoanalysis, the creative processes have also been described as constituting a third space. Beyond Freudian primary and secondary processes, they work with their own dynamics, creating spaces of alleged opposites (Héctor Fiorini, The Creating Psyche: Theory and Practice of Tertiary Processes, Vitoria-Gasteiz: Agruparte, 2010).

[90] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina, p.88.

[91] Eva Marxen, “‘La comunidad silenciosa’. Migraciones Filipinas y capital social en el Raval (Barcelona),” Ph.D. dissertation, University Rovira i Virgili, (2012). http://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/96667/ TESIS.pdf?sequence=1.

[92] Cusicanqui’s Sociology of images certainly achieves decolonization. Yet, the use of images (whether producing or reading them) does not automatically imply a critical approach but should include the awareness of eventual “false democratizations” and instrumentalizations (Manuel Delgado, “Cine,” in De la investigación audiovisual. Fotografía, cine, vídeo, televisión, edited by Maria Jesús Buxó and Jesús Maria de Miguel, Barcelona: Proyecto A Ediciones, pp.49-77; Eva Marxen, “Artistic Practices and the Artistic Dispositif. A Critical Review;” Pierre Bourdieu and Hans Haacke, Free Exchange).

[93] Ernesto de Martino, El folclore progresivo y otros ensayos (Barcelona: MACBA/Bellaterra: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, 2008).

[94] Umberto Eco, Dalla periferia dell’impero (Milan: Bonpiani, 1977). Regarding the consumerist appropriation of subaltern culture by hegemony see: Jesús Martín-Barbero, De los medios a las mediaciones. Comunicación, cultura y hegemonía (Mexico City: Gustavo Gili, 1987) and Néstor García Canclini, Consumidores y ciudadanos. Conflictos multiculturales de la globalización (Mexico City: Grijalbo, 1995).

[95] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina; Julieta González, “Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985.”

[96] Ernesto de Martino, Magic: A Theory from the South, translated by Dorothy Louise Zinn (Chicago: Hau Books, 2015); El folclore progresivo y otros ensayos; The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism, translated by Dorothy Louise Zinn (London: Free Association Books, 2005); La fine del mondo. Contributo all’analisi delle apocalissi culturali (Turin: Einaudi, 1977); Morte e pianto rituale nel mondo antico: Dal lamento funebre antico al pianto di Maria (Turin: Einaudi, 1958). In Latin America, movements such as anthropophagy, developed by Oswald de Andrade (1928) and manifest in artworks such as Abaporú (1928) or Anthropophagy (1929) by Tarsila do Amaral, had opposed the impositions of colonialist culture. They developed a new approach by ingesting the colonial to produce something new, based on local cultures, like the Brazilian Indigenous and Afro Brazilian. The final objective is to create something original by breaking with fixed places, as well as spatial, cultural, and social boundaries.

[97] Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Sociología de la imagen. Miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina.

[98] Ibid., p.91.

[99] Ibid.

[100] Boaventura de Sousa Santos, The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South, p.72.

[101] MACBA, 2018 exhibition text of Masotta’s retrospective show with its so excellently chosen title Theory as Action.

[102] Ana Longoni, “Oscar Masotta: vanguardia y revolución en los años sesenta,” p.22.

Spanish Version

Oponiéndose al Imperialismo Epistemológico

Eva Marxen

Traducción del inglés al español: Luisa Ospina y Gloria Henao

Este artículo se enfoca en la extremadamente rica herencia de prácticas artísticas de Latinoamérica, que han tomado la forma de resistencia contra la opresión social, económica y política pasada y presente. Muchos artistas, activistas del arte y grupos, han desarrollado y llevado a cabo obras de arte, prácticas e intervenciones artísticas extremadamente sofisticados, basados en un pensamiento crítico riguroso, y orientados por principios de colectividad, que han derivado en un simbolismo altamente efectivo. Como resultado de los esfuerzos para desafiar el discurso hegemónico, han podido oponerse con éxito a los mecanismos de control y opresión de la sociedad, generando espacios para la resistencia y para narrativas alternativas que, con el tiempo, pueden lograr un cambio social y político. Recientemente, se han creado muchos trabajos que se oponen de manera exitosa al saqueo y la explotación del medio ambiente. Por ejemplo, el dúo argentino Iconoclasistas (sobre quienes se habla en esta edición) trabaja con el concepto de una cosmovisión rebelde. Esto implica una visión crítica y un mapeo del extractivismo, la explotación medioambiental y neocolonial, así como una ecología política. Sandra de la Loza y Eduardo Molinari se han dedicado a la investigación transnacional (desde Los Ángeles y Buenos Aires) acerca de la producción de espacio, economías extractivistas, desplazamiento, y la sabiduría indígena tanto eclipsada como viviente. Esta última ha comprendido la importancia del diálogo y de la coexistencia con la naturaleza y con los no humanos por cientos de años, pero la historia dominante ha ignorado esta sabiduría.[1]

Ejemplos de Imperialismo en las Artes

En Suramérica y Centroamérica, los artistas locales con frecuencia han sido precursores de prácticas artísticas y pensamientos que más tarde han sido promovidos en Norteamérica y Europa como nuevos e innovadores, recibiendo pocas veces crédito por sus históricas contribuciones. Un ejemplo sería la “desmaterialización de las artes”. En Argentina, Oscar Masotta [2] mencionó la desmaterialización del arte en el mismo año que Lucy Lippard, habiéndose declarado esta última como la primera en hacerlo.[3] También en 1967, Oscar Masotta dio una conferencia en el Instituto DiTella (centro del avant-garde artístico en Buenos Aires) titulada “Después del pop, nosotros desmaterializamos”. Él se refirió a un artículo del Constructivista ruso El Lissitzky, publicado originalmente en 1926. Lissitzky defendió “la integración de artistas en la industria editorial a través de nuevas tipografías y diseños. El artista avant-garde ruso estaba abogando por los libros como una forma de arte por sus posibilidades de expresión, y su capacidad para tomar muchas formas, señalando que ‘la desmaterialización es la característica de la época’” en la que las nuevas tecnologías de comunicación resultan en la disminución de la materialidad física, y el aumento de “energía liberadora. Masotta retomó este concepto, considerándolo en términos de procesos artísticos contemporáneos y formas de comunicación” que buscaban disolver el arte en la vida social.[4]

Estoy de acuerdo con Ana Longoni y Mariano Mestman en que se gana muy poco en “disputas estériles sobre los derechos de propiedad intelectual de una noción de hace cuarenta años”.[5] “El punto más bien es pensar en estos eventos que coincidieron como parte de una red transnacional de la circulación de ideas”, en lugar de enfocarse en la suposición y el mercadeo que implican determinar cuál autor fue el “primero” en expresarlas. Masotta comenzó su carrera con estudios universitarios en filosofía sin concluir en su ciudad natal, Buenos Aires. Sus actividades incluyeron crítica literaria, el estudio del avant-garde artístico, cultura de masas (particularmente cómic) y psicoanálisis Lacaniano. Se desempeñó como escritor, artista, crítico y productor, así como el facilitador de grupos de estudio en todos los campos mencionados. Situado en las antípodas del “especialista” científico contemporáneo, su paso por diferentes campos y su creación de conexiones inesperadas también ha sido relacionada con sus orígenes en grupos intelectuales de Buenos Aires durante los años cincuenta y sesenta que desarrollaron “relaciones entre corpus teóricos que en los países [así denominados] centrales] rara vez se leían conectadamente”.[6] Tenía una capacidad extraordinaria para incomodar, moverse hacia y entre lugares inusuales, y anticipar nuevos desarrollos intelectuales. En este sentido, estaba en una búsqueda constante de nuevas explicaciones a nuevos sucesos.[7]

En 1998, el curador francés Nicolas Bourriaud afirmó haber introducido el concepto de “estética relacional”. Sin embargo, artistas como Lygia Clark ya habían trabajado en los ochenta, de manera mucho más intensa, estableciendo espacios relacionales de subjetividad.[8] En su última fase, desde 1976 hasta su muerte en 1988, la artista brasileña desarrolló La Estructuración de un self. Se trataba de una práctica artística que era terapéutica, y que fusionaba los límites entre el arte y la terapia. Trató a participantes/clientes de manera individual, durante un tiempo predeterminado, con la ayuda de los “objetos relacionales”. Como su nombre lo indica, lo importante era la relación establecida con la fantasía del sujeto. La idea de Clark era exorcizar del cuerpo lo “fantasmático”, que ella ubicaba allí. Ella consideraba lo fantasmático como la consecuencia de experiencias traumáticas que bloquean el potencial creativo del ser humano. Debe ser aliviado, tratado y transformado en el espacio del cuerpo, con la ayuda de los objetos relacionales, o por medio del contacto directo de las manos del artista-terapeuta. Los objetos relacionales estimulaban y movilizaban la memoria afectiva debido a su textura, y a la forma como Clark los manipulaba y los manejaba. Las sensaciones físicas de estos objetos eran el punto de partida para una elaboración más profunda de lo fantasmático. Las personas recuperaban su salud cuando se conectaban con su cuerpo vibrátil, que permitía una reconexión con su poder y energía creativa.[9]

El significado político de su trabajo era sumamente importante, ya que la misma Clark había sido testigo de primera mano—y también a través del sufrimiento de sus pacientes—de los terribles efectos de la dictadura y la censura. Este terror se impuso en el potencial creativo de la población brasileña, limitando su expresión y su capacidad para la simbolización, con consecuencias obviamente nocivas para su salud mental. En términos de Donald Winnicott, en una dictadura no hay espacio potencial para la experiencia cultural y creativa a un nivel macro.[10] Clark actuó como una artista-terapeuta en el umbral entre la dictadura y el neoliberalismo de Brasil. Las dictaduras militares de diferentes países latinoamericanos habían dañado el espacio potencial para la experiencia creativa. Más tarde las nuevas dinámicas impuestas del neoliberalismo trataron de reanimar las actividades y expresiones artísticas, pero únicamente usándolas como un instrumento ideológico y comercial. Clark ya había previsto un desarrollo que, en años recientes, ha ganado bastante en términos de sofisticación: la instrumentalización del arte por medio de dinámicas capitalistas, manifiesta concretamente en la forma de fundaciones “sin ánimo de lucro” pertenecientes a compañías multinacionales, que, a través del patrocinio del arte, la cultura, el trabajo social, etc., acumulan capital simbólico que sirve principalmente para ocultar actividades capitalistas no populares.[11]

De esta manera, las obras de arte de Clark pueden considerarse simultáneamente como expresiones artísticas, políticas y clínicas. Ella no deseaba abandonar el arte ni cambiarlo por la práctica clínica, sino más bien “habitar la tensión de sus bordes … para que ambos puedan recuperar su potencial de critica del modo dominante de subjetivación”.[12] Rechazando una percepción del arte limitada al objeto-forma, optó por realizar obras de arte en el cuerpo del receptor, para que la persona se desarrollara de un espectador pasivo a un participante activo. Buscó una relación intensa entre arte y persona, y arte y vida. La vida en sí debería ser un acto de arte que trata directamente esferas sociales, psicológicas, políticas y corporales.[13] Siguiendo esta experiencia arte-vida según lo desarrollado por Lygia Clark, y también por su amigo Hélio Oiticica, el arte se concebía para funcionar “como un vehículo para la liberación del sujeto, en el que este podía, a través de la experiencia creativa, recomponer su propia subjetividad y reconectar arte y realidad”.[14]

De manera crítica, la “estética relacional” de Bourriaud ha sido considerada “inmovilista y regresiva en la medida que ‘estetiza’ el paradigma inmaterial y comunicativo y los procesos sociales y creativos que le son implícitos, al imponerles un régimen exhibitivo que interrumpe su movilidad y que congela y fetichiza las prácticas.”[15] El resultado, de acuerdo con Jorge Ribalta, es “una cosificación perversa tanto del activismo político como de las nuevas formas de producción inmaterial, afectiva, comunicativa y relacional del pos-fordismo.”[16] En otras palabras, “estetiza… nuestra economía de servicio (‘invitaciones, sesiones de casting, encuentros, áreas amigables y user-friendly, citas’)”.[17] Por el contrario, Clark fue más allá de esta anestesia y apuntó a una “experiencia poética vivida” para la recarga y el cambio subjetivo.[18] Su colega brasileño Oiticica “también sentía esta necesidad de matar el [concepto del] espectador o participante”. Él estaba estrictamente en contra de las insufribles “experiencias aburridas” o “participación superficial”. Junto con Lygia Clark, aspiraban a anular la relación sujeto-objeto, en favor de “una práctica interpersonal que lleve hacia una comunicación verdaderamente abierta: una relación yo-tú . . . ; ningún beneficio corrupto . . . debería esperarse.”[19]

Pocos artistas y pensadores del Sur han recibido crédito por sus trabajos previos altamente relevantes. Durante las últimas décadas, el arte basado en la comunidad y el arte socialmente comprometido se han propagado rápidamente por la práctica artística y la academia norteamericanas. En consonancia con el show Actuar y hablar, las raíces intelectuales, metodológicas, culturales y políticas de estas prácticas han sido revividas en Latinoamérica, siendo el objetivo de “orientar los legados del pasado” mediante una “cartografía alternativa.”[20]

La Economía Política y Colonial del Conocimiento

Diversas formas de imperialismo epistemológico son evidentes en la economía política del conocimiento global, la subjetivación capitalista, así como la cooptación de conocimiento y prácticas alternativas. Los artistas han podido expresar y denunciar las formas de imperialismo epistemológico incorporadas en esta economía política global opresiva por muchos años. Este sistema fue iniciado al menos hace medio siglo por, entre otras instituciones, la Universidad de Chicago en forma de becas para los denominados “Chicago Boys”, estudiantes chilenos del economista Milton Friedman, quienes estudiaban neoliberalismo de primera mano con el fin de implementarlo en su país natal, llevando a atroces violaciones de los derechos humanos. Son especialmente interesantes en cuanto a esto las siguientes películas acerca de los Chicago Boys: La Batalla de Chile I-III (1976-98) por Patricio Guzmán; La Conspiración (2006; título original: Héros fragiles: Chili 1973. Affaire non classée) por Emilio Pacull; Chicago Boys (2015) por Carola Fuentes y Rafael Valdeavellano, y el video epónimo de Juan Downey de 1983. Todos muestran cómo la violencia militar y estatal fue aceptada como medio para el fin de expandir el neoliberalismo desde el Norte hacia el sur. Hoy en día en Chile [21], las protestas más persistentes, creativas y resistentes han sido organizadas para cambiar profundamente o para abolir completamente a este mismo sistema neoliberalista.

El neoliberalismo fue implementado de manera cruel, y objeto de propaganda como una forma de progreso, modernización y desarrollo. Los autores Latinoamericanos han jugado un papel principal en el análisis del concepto de “colonialidad”, articulado por el sociólogo peruano Aníbal Quijano [22], y definido por Walter Mignolo [23] como interesado en abrir “la reconstrucción y la restitución de historias, subjetividades, conocimientos y lenguajes silenciados, reprimidos y subalternizados por la Totalidad representada bajo los nombres de la modernidad y la racionalidad”.[24] A cambio, el marco de la Colonialidad/Decolonialidad ofrece “estrategias de resistencia hacia una modernidad que perpetua la condición colonial.” Esta “opción descolonial o la desvinculación” ha tomado “formas de la desobediencia epistémica y el pensamiento fronterizo.”[25] En su artículo “Memorias del subdesarrollo. Arte y giro descolonial en América Latina, 1960-1985” (parte de una exhibición y catálogo con el mismo nombre), la curadora Julieta González señala correctamente que “este tipo de reflexión en el campo cultural va más allá del grupo Modernidad/Colonialidad/Decolonialidad”.[26] Desde las ideas de concientización y desecolarización en las décadas de los 60 y 70 de Paulo Freire e Ivan Illich, hasta la Filosofía de liberación [27] de Enrique Dussel, o las Culturas híbridas de Néstor García Canclini [28], encontramos una gama de pensadores que proponen “estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad; más recientemente, varios teóricos han argumentado a favor de las epistemologías del Sur, como aquellas que ‘representan adecuadamente las realidades del Sur Global’”.[29] E incluso antes, o simultáneamente, muchos de los escritores y académicos mencionados anteriormente, ideas similares “habían sido anticipadas en las artes plásticas, la arquitectura y el cine, en diversas localidades de América Latina, a partir de comienzos de la década de 1960.”[29] El objetivo de la exposición Memorias del subdesarrollo producida en el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de San Diego, ha sido precisamente “identificar y cartografiar algunas instancias significativas de este giro descolonial en el arte y la cultura como una parte importante de la historia del arte contemporáneo.”[30]

Epistemologías del Sur

Más recientemente, pensadores como Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui [31] o Boaventura de Sousa Santos se han enfocado en el “epistemicidio” [32] cometido por el “imperio cognitivo”, y han hecho un llamado a las prácticas de destotalización y descolonización para desafiarlo. Para Santos, estas prácticas deben ir de la mano con un pensamiento transformador.[33] Comienza con cuestionar las bases epistemológicas y la manera de pensar en sí: “No necesitamos alternativas; más bien necesitamos un pensamiento alternativo de alternativas”, como argumenta Santos.[34] En el libro de Santos, El fin del imperio cognitivo: La afirmación de las epistemologías del Sur, uno de los principales objetivos de las epistemologías del Sur se describen en términos del esfuerzo por parte de “grupos sociales oprimidos [para] representar al mundo es sus propios términos, para cambiarlo de acuerdo con sus propias aspiraciones”, con el fin de desafiar los discursos de desarrollo y una forma de “modernidad que perpetúa la condición colonial.”[35] Por el contrario, las epistemologías del Norte “han contribuido a convertir el conocimiento científico desarrollado en el Norte global, en una manera hegemónica de representar el mundo como propio, y de transformarlo de acuerdo con las propias necesidades y aspiraciones. De esta manera, el conocimiento científico, combinado con un poder económico y militar superior, entregaron el Norte global el dominio imperial del mundo en la era moderna y hasta nuestros días”.[36] De este modo, las epistemologías del Norte reproducen el capitalismo, el colonialismo y el patriarcado, así como la opresión y la represión causadas por esta tríada imperialista. Ellos conciben sus epistemologías eurocéntricas “como la única fuente de conocimiento válido” en un escenario en el que el Norte es la solución, y el Sur es el problema. Durante siglos el Norte ha fallado al no considerar amplios cuerpos de conocimiento como válidos, lo que ha llevado a un epistemicidio masivo, una masiva “destrucción de una inmensa variedad de saber”, y en consecuencia a un desempoderamiento de sociedades enteras.[37]

Sin embargo, aunque se resisten y se oponen al epistemicidio, el objetivo de las epistemologías del Sur no consiste simplemente en reemplazar una hegemonía por otra, como poner las epistemologías del Sur en el lugar de sus contrapartes dominantes del norte. El Sur más bien se rebela “para superar la dualidad normativa existente”, y busca vencer “la dicotomía jerárquica entre el Norte y el Sur”, eliminando “las jerarquías de poder que los habitan”.[38] “Las epistemologías del Sur no son diametralmente opuestas a las epistemologías del Norte, en el sentido de poner un único conocimiento válido en contra de otro”.[39] Asimismo, la noción del Sur no es geográfica sino anti-imperial. Se relaciona tanto con el colonialismo histórico como con el colonialismo interno. Es por eso que puede ser aplicada simultáneamente al Norte y al Sur en el sentido geográfico.

Santos propone una sociología de la ausencia y una sociología de la emergencia. La primera consiste en recuperar las epistemologías del Sur y convertirlas de ausentes a existentes: redimirlas es visto como un “gesto eminentemente político”.[40] La sociología de la ausencia se describe como “la cartografía de la línea abisal. Identifica las maneras y los medios mediante los cuales la línea abisal genera no existencia, invisibilidad radical e irrelevancia… el colonialismo de poder, conocimiento y ser, funciona en conjunto con el capitalismo y el patriarcado para generar exclusiones abisales, es decir, para hacer que ciertos grupos de personas y formas de vida social sean inexistentes, invisibles, radicalmente inferiores, o radicalmente peligrosos – en resumen, como descartables o amenazantes”.[41] Y peor aún: Cualquier conocimiento susceptible de subvertir el orden capitalista, patriarcal, colonial, ha sido violentamente reprimido. “El conocimiento como regulación terminó por canibalizar el conocimiento como emancipación”.[42] Esto se ve reflejado en la fase actual del neoliberalismo en forma de la creciente dependencia y cooptación de la comunidad científica por parte de entidades capitalistas extra científicas. Estas últimas determinan la economía política de ideas, y monopolizan las ecologías y la pluralidad de conocimientos.[43] En general, “dado el impulso capitalista de mercantilizar el conocimiento científico, y en consecuencia de reducir el valor del conocimiento científico a su valor en el mercado, y con el sometimiento subsiguiente de la investigación en universidades y centros de investigación a criterios de utilidades a corto plazo, el pluralismo científico puede desvanecerse, particularmente en aquellas áreas que se han vuelto campos codiciados para la acumulación de capital”.[44]