Book Review: Sociopolitical Aesthetics. Art, Crisis and Neoliberalism

Denisa Tomkova

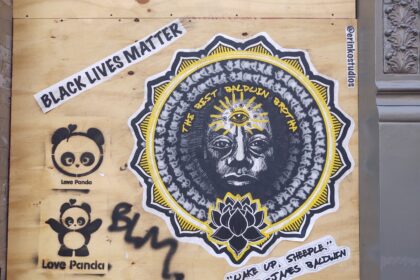

Sociopolitical Aesthetics. Art, Crisis and Neoliberalism (Bloomsbury, 2021) by Kim Charnley is part of the book series, Radical Aesthetics – Radical Art (RaRa), initiated in 2009 by Jane Tormey and Gillian Whiteley. The aim of the series is to examine the relationship between art and politics in the context of debates in the field of contemporary art theory relating to the proliferation of ‘socially engaged’, ‘relational’, ‘participatory’ and ‘collaborative’ practices. Charnley’s book then, as the editors argue, “interrogates the conditions of critical art under late capitalism.” (xii) The book situates its study within the recent moments of crisis – the ‘migrant crisis’, Black Lives Matter protests, the Brexit vote, Trump election and the most recent Corona pandemic. Charnley, referring to Martha Rosler, positions the main question posed by his book whether systemic disorder ‘will alter, or has already altered, the process of radical art’s ‘absorption and neutralization.’ by the ideological structures, political orders and art institutions. (4)

The book is divided into five chapters, in addition to the Introduction and Conclusion. The first chapter of the book, “The Art Collective as Impurity,” addresses art collectives, which are understood in opposition to individualism and to the “normal functioning of art.” (18) [emphasis added] The second chapter, “The Temporality of Institutional Critique”, examines Institutional Critique’s precarious position between critical/political art and its incorporation by the canon. The following chapter, “Relational Aesthetics and Collectivity,” discusses collectivity through the prism of Nicolas Bourriaud’s ‘relational aesthetics’ theory, in which human relations become the main query of the art projects. The chapter aims to address the relationship between collective artworks and the commodity form through analysis of relational aesthetics based on an examination of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s works from the 1990s. The fourth chapter, “Social Practice,” predominantly focuses on the term “social practice” which the author places to the year 2011, identifying Shannon Jackson as one of the first to use this term (Jackson, Shannon. 2011. Social Works. Performing Arts, Supporting Publics, Routledge). The final chapter, “Slogans and Militancy,” addresses the relationship between the social turn and the changes undergone by the art institution under neoliberalism, in particular during Brexit in Britain, and examines collectivity through the politicized language slogans.

Geographically, the book examines the region of the Global North, in particular the United States and the United Kingdom. The author explains this decision by stating that: “Although the social turn is a global phenomenon, with important traditions of collective practice in Latin America, Asia and Africa, it has proved easier to address the ideological dynamic of the art institution by using case studies that are proximate to power centres of the art world.” (20) When considered from the Anglo-American perspective, the author’s selection decision is valid. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the book provides a global examination of critical art’s condition under late capitalism in general. Hence, the book’s argument would have been more accurate and precise if its analysis was presented from an exact spatial-temporal position. If, for instance, the book focused specifically on the social practice in the UK during Brexit, it would not only have made it more distinct, but also it would have made it more relevant to current issues. One example can be seen in Charnley’s analysis of the growing interest in politics that artists developed in the 1960s and 1970s in the US, the UK and Europe. This is described as a “left shift;” this would have a very different context and circumstance in the former Eastern Europe. While the author shows his self-awareness by speaking about the “ease” of using examples from the US and the UK, there have been other ‘crises’ which have strongly affected different cultural productions and responses from contemporary critical art around the world, and their inclusion would have strengthened the book. Therefore, it might have been more accurate and effective to precisely situate the author’s spatial-temporal framework, as well as to define the specific case studies and their context more explicitly.

To deliver the book’s argument, Charnely introduces a new terminology, “Sociopolitical Aesthetics”, and explains that: “It is used in this book to identify the interweaving of socially engaged, collaborative or participatory art practices and debates about aesthetics since the turn of the millennium.” (4) While Charnely admits that the term itself is problematic and messy, he claims that this is precisely his intention, as it reflects the messiness of the development encompassing many categories, such as: relational aesthetics, dialogic art, institutional critique, art activism and social practice, among many others. This new terminology aims to stress the shift by artists from social concerns to the political significance of their art. Although Charnley argues that the “debates that initiated the social turn are no longer current, precisely because socially engaged artistic strategies are now incorporated into the normal repertoire of contemporary art…”, he revisits the “social turn” to examine the process of radical art’s absorption and neutralization by the art institution. Positing the social turn as a return to the revolutionary avant-garde, the author explores the potential of socially engaged art as a collective to represent an opposition to individualism, fragmentation and to neoliberalism as a whole. Charnely concludes that even though the social turn represents a return to avant-garde principles, because of its challenge to individualism, sociopolitical aesthetics then become a “limit point.” (28) He argues that: “Contemporary art, in its theoretical references and its aesthetic conventions, is shaped by the residues of revolutionary ambition. There is a latent militancy in the strategies of avant-gardes, even though they have been institutionalized, which takes on a different meaning in the times of social and political instability.” (187) However, the question of art’s autonomy from the social system has already been discussed in depth by many critics: Angela Dimitrakaki, Grant Kester, John Roberts, and Gregory Sholette, among many others. In particular, in relation to the avant-garde, Dimitrakaki argues that: “[Socially engaged art] must therefore deny its identity as an experimental form of unknown outcome played out in the biopolitical terrain with the purpose of leading a system-wide transformation – which is what makes it an avant-garde.” [1] What she means is that contemporary (socially engaged) art is not autonomous and cannot exist ‘outside’ of the system in an autonomous art zone, it is created within the system and is dependent on it. Therefore, as a new theory, Charnely’s argument does not bring much new reading into the well-established discourse of art’s autonomy. What is more valuable is his new original reading of specific art practices presented in the book.

For instance, when focusing on the local context, the book provides an insightful and pertinent analysis of inequality in Britain through an examination of Mark Storor’s Baa-Baa Baric: Have you Any Pull?, ongoing since 2015. The project took place in the post-industrial town of St Helens, one of the most deprived areas of the UK, and represents in its duration the average lifespan of male residents of St Helen’s, which is 10 years lower than in the wealthiest areas in the UK. Here, the author not only provides a valuable analysis of the project, but also gives an insightful reading into the proliferation of social practice after Brexit. He explains that: “In the wake of the vote to leave the EU, a larger proportion of funding has been oriented towards projects that promise to include or address the demographic groups that made themselves heard in the referendum.” (149) Charnely very accurately observes here that “Brexit made self-evident the political instability created by the democratic deficit of neoliberalism.” (149) He observes the potential of social practice in challenging the divisions preserved by the art institution.

The third chapter discusses collectivity through the prism of Bourriaud’s “Relational Aesthetics.” The author admits that Bourriaud’s work is no longer current but observes the influence that it had in artistic developments in the early 2000s. Charnely continues with an already well-established analysis of the theoretical dissensus between Claire Bishop’s aesthetic antagonism and Grant Kester’s ethical engagement and dialogue. I will not go in depth here, as the FIELD journal has already published an in-depth analysis and critique of Bourriaud’s theory by Jason Miller in 2016. [2] Charnely argues in contrast to Bourriaud, that relational aesthetics “is an artform that conceives social encounters as a material, rather than merely a context of art making.” (88) This is precisely what Charnely contributes to the theory and where he shifts perspective from Bourriaud’s argument. He offers a new convincing analysis of Gonzalez-Torres’s works in relation to neoliberalism, consumer culture, the circulation of objects and accumulation. His analysis understands paper stacks and candy spill as a metaphor for consumerism under capitalism, arguing that these works “stage a speculative togetherness within the circulation of objects, which is quite possibly all that remains of community under neoliberalism.” (121) He adds that: “This identification of the post-relational work with an original encounter tends to idealize immediate experience, either as dialogue or antagonism. The ‘endless supply’ that forms the horizon of the stacks and candy spills, better evokes the fragmentation that is implicit in collectivity.” (115)

Further, the book also correctly observes that social practice “may provide a distinctive insight into the fragility of institutions of civic life now.” (133) As rightfully stated by the author, these art projects are able to shed light on, and provide a way to understand, inter-related crises caused and impacted by the Brexit Referendum. “A central theme in social practice is the refashioning of sociopolitical aesthetics to respond to crisis situations. This approach to crisis is driven by the actual and undeniable instability of the global order.” (132)

In summary, the book provides some new insightful readings of established theories and practices through the lens of new crises. The author’s scope of socio-political aesthetics is based around the concept of the collective. He understands collectivity as a central objective of sociopolitical aesthetics, but also argues that: “In social practice, the idea of a collective work of co-presence becomes a model of cooperation that can never quite resolve the social crises that it makes visible.” (188) However, what is this collective? Charnely argues that in principle, the art collective challenges individualism. Here, I would like to bring attention to the recent special issue of e-flux journal, edited by Zdenka Badovinac and dedicated to “The Collective Body” (Understood as collectivity, togetherness, or a community.) during the recent pandemic, where the authors provide new profound readings on the emergence of an alternative collective body during the times of current crises. Crises give us an opportunity to consider new forms of cultural production and to imagine new kind of institution that could serve as many of us as possible. Although Charnely observes that an art collective cannot resolve the social crises that it makes visible, however; as Ana Vujanović argues, it “can encourage us to rethink this ontology by foregrounding collective processes of identity formation. … we can take it as an invitation to train our imagination for the epistemological performance of living together as individuals in a life always populated with others.” [3]

Overall, the book Sociopolitical Aesthetics. Art, Crisis and Neoliberalism promises to examine the relationship between art and politics in the time of the most recent crisis, more specifically under Brexit and the Corona pandemic. The counter narratives and public discourses are provided largely by contemporary artists, who are now more than ever struggling for survival due to the harsh economic conditions which the current global pandemic has imposed upon them, but this has remained mostly unexposed by this book. Even though the book cannot be seen as a comprehensive study of art, crisis and neoliberalism globally, it provides some very insightful readings of social practice created in the UK in the context of Brexit. The book also provides a basis and direction for further research, and constitutes a steppingstone for the future study of the contemporary crisis condition and its relationship to contemporary art in the Global North and beyond.

Denisa Tomkova is a Curatorial and Publications Research Fellow at the SixtyEight Art Institute in Copenhagen. She holds PhD in Visual Culture from the University of Aberdeen (2019) and an MSc in Modern and Contemporary Art: History, Curating and Criticism from The University of Edinburgh. Her PhD research focused on socially engaged art from the Czech-Republic, Slovakia and Poland. Between 2015- 2018, she was a member of the international research project ‘Comparing WE’s. Cosmopolitanism. Emancipation. Postcoloniality’ based at the University of Lisbon. Between 2019-2021, she worked for the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC) in Berlin, as a research fellow, curator and a project coordinator. Between October 2020 – April 2021, she was a curator for the Secondary Archive project – an online platform devoted to the work of female artists from Central and Eastern Europe from the 1960s onwards.

Notes

[1] Angela Dimitrakaki, The Avant-Garde Horizon: Socially Engaged Art, Capitalism and Contradiction This paper was presented at the public forum Socially Engaged Practice: Ethics, Aesthetics, Politics or Economics?, on 3 March 2013, CCA Glasgow, with Austrian collective WochenKlausur. The public forum was organised in the context of the curatorial project ECONOMY in Edinburgh and Glasgow, January to April 2013, p. 6

[2] Jason Miller. 2016. ‘Activism vs. Antagonism: Socially Engaged Art from Bourriaud to Bishop and Beyond’ in FIELD. A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism. Accessed on August 17, 2021: http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/issue-3/activism-vs-antagonism-socially-engaged-art-from-bourriaud-to-bishop-and-beyond

[3] Ana Vujanović. 2021. ‘The Collective Body of the Pandemic: From Whole to (Not) All in e-flux. Accessed on August 17, 2021: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/119/400150/the-collective-body-of-the-pandemic-from-whole-to-not-all/