At the Source (Code): Obscenity and Modularity in Rokudenashiko’s Media Activism

Anne McKnight

Timeline

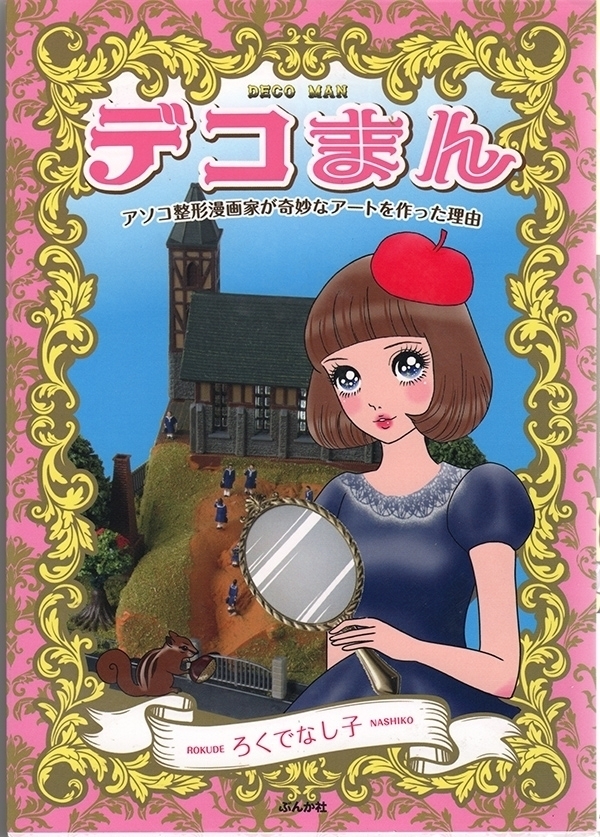

June 30, 2012 – Decoman manga published

June 18, 2013 – Crowd-funding campaign for “man-boat” begins; ends September 6

July 12, 2014 – First arrest

July 18, 2014 – Released on bail

March 2014 – Launch of “man-boat”

December 3, 2014 – Second arrest

December 26, 2014 – Released on bail

April 3, 2015 – What Is Obscenity? (ワイセツって何ですか?) published

April 14, 2015 – Trial begins in Tokyo District Court

May 20, 2015 – My Body Is Obscene?!: Why Is Only My Lady Part Taboo? (私の体がワイセツ?女のそこだけなぜタブー) published

February 1, 2016 – Prosecutor states intent to seek fine of eight hundred thousand yen but no prison term

May 8, 2016 – Tokyo District Court hands down mixed verdict. A four hundred thousand-yen fine is imposed for distributing 3-D printer data over the Internet, but Rokudenashiko is acquitted on charges from the July 2014 gallery arrest of “displaying obscene materials publicly.” Rokudenashiko and her team vow to appeal

![[Figure 1: Rokudenashiko stands by her “man-boat” kayak, whose top attachment was modeled on her vulva, on the banks of the Tamagawa River. (Credit: Taishiro Sakurai)]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig1-768x1024.jpg)

The Source of Activism

On a fine spring day in March 2014, the artist Rokudenashiko, known legally as IGARASHI Megumi, set sail on a voyage down the Tamagawa River, a major waterway that empties into Tokyo Bay, where it connects to the open seas.(1) The boat was featured in later news reports not only for its cute rubber-ducky look and handcrafted aesthetic; more notoriously, Rokudenashiko’s voyage down the Tamagawa River ultimately landed her in jail and on trial for obscenity. This innocuous-looking boat and other works of DIY sculpture provoked two arrests at the same time that the media splash over the artist’s works, many of which were confiscated by police along with her computer and launched Rokudenashiko into coverage in the news, in flagship journals of music and art criticism, and even in mainstream women’s magazines and blogs, where response has been even more supportive outside Japan than inside.

While Rokudenashiko’s works provoked outsized reactions in Japan, at the same time, awareness of her trial plugged her into a global cohort of artists that includes iconic Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei. Following Rokudenashiko’s June 2015 visit to Beijing to meet Ai, an exhibition of her work took place in Hong Kong in the fall of 2015 with the aim of “thinking feminism via the works of artists from Japan and Hong Kong.”(2) The show featured contributions from the internationally known contemporary artists AIDA Makoto and Sputniko!. News of Rokudenashiko’s arrest and trial has been the subject of a documentary feature on Vice magazine’s new women-geared channel Broadly, and the technorati blog Boing Boing posted its related story, written by editor in chief Mark Frauenfelder, under the tags “art,” “censorship,” “hypocrisy,” and “war on women.” (3)

Rokudenashiko’s arrest conferred on her the honor of being the first woman in Japanese history tried on grounds of obscenity as spelled out in Article 175 of the Criminal Code of Japan.(4) The trial began in April 2015 and served as a venue for Rokudenashiko to challenge a double standard that judges the representation of women’s bodies in starkly different terms than that of male bodies.(5) Rokudenashiko’s works link to existing lines of feminist art that employ new media, challenge the sexual politics of the art world in their crafting of digital cultural forms, and create a persona for activism based on humor and the customization of mass cultural forms via craft.

In the following sections I map the legal case against Rokudenashiko as Megumi Igarashi. Then I turn to explore the formal composition of two types of works, figures and dioramas, and the processes of their making as prototypes of modular aesthetics. Finally, I situate Rokudenashiko’s work in the broader context of cute aesthetics to show how she uses modular forms to engage with processes of everyday life, not only suggesting critique but modeling alternatives to the fantastically plastic ways that women’s bodies are imagined under Abenomics. This set of policies, typically presented as a salve to a national crisis of degrowth, imagines women to be available for any and all jobs at hand, from care giving for the elderly, to child rearing, to upward climbs through the glass ceiling of corporate life.(6)

This essay argues that the aesthetic of Rokudenashiko’s DIY projects—which I call modular aesthetics—is a powerful case of speculative design with resonance in Japan as well as in transnational fields of digital and craft-based art. Though her media—which include sculpture, dioramas, and figures—replicate parts of the body that are often sexualized, the works themselves are not about eroticizing those body parts. Bawdy, meticulously crafted, and funny, Rokudenashiko’s sculpture work draws on the traditionally low tones of art found in craft to offer media theory an invitation to “low theory.” “Low theory,” in McKenzie Wark’s turn of phrase, is an attempt to connect ideas with life processes using what he calls “the labor point of view,” with an eye to the infrastructures and collaborations that connect the art work to the cultural work.(7) In this case, the lowness comes in the common or mass-produced materials as well as the perceived vulgarity of subject matter. The kayak is made of a customized insert attached to a mass-produced base; the dioramas are meticulously handcrafted with art materials and found objects on top of an alginate cast; and the figures are cast from plastic. Rokudenashiuko’s low-theory use of new media forms in the digital age poses questions about how material (usually female) bodies might be meaningful beyond ways they are conventionally morcellized and sexualized in a commodity-based market of images.

Rokudenashiko’s use of her own body as a raw material for dematerialized art making is a call for a return to experience, to grasping how one’s own body can be understood in the same terms as other media—specifically other plastic media. The question of how a body might be a medium and its experiences revalued in a better future is characteristic of the field of speculative design. According to Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, this field is guided by

the idea of possible futures and using them as tools to better understand the present and to discuss the kind of future people want, and, of course, ones people do not want. The[se projects] usually take the form of scenarios, often starting with a what-if question, and are intended to open up spaces of debate and discussion; therefore, they are by necessity provocative, intentionally simplified, and fictional. Their fictional nature requires viewers to suspend their disbelief and allow their imaginations to wander, to momentarily forget how things are now, and wonder about how things could be.(8)

In both small plastic sculptures and digitally produced 3-D-printed objects, Rokudenashiko’s body is presented as just such a “necessity provocative, intentionally simplified, and fictional” prototype that imagines such better futures beyond the tired tits-and-eyes images, pixelated genitals, and fetishized body elements seen in commercial representations of the female body that overvalue parts (breasts, genitals, etc.) at the expense of not only a whole but of any other context or value. In the words of the digital historians Alan Galey and Stan Ruecker, one goal of the prototype designer “has been deliberately to carry out an interpretive act in the course of producing an artifact.”(9) In this case, interpretation comes from the speculative questions that arise from interpreting the artifact of the female body as something re-signifiable, whose meaning may shift into new narratives—not guaranteed to be better in terms of female power, but at least different, with potential. What if your body were just another surface or backdrop—like a rolling lawn, the moon, or a golf course? Would you disappear into the background like camouflage? Or would you be framed into another narrative? Or made meaningful as a stand-alone entity in an entirely other way?

Rokudenashiko calls her works manko—named for the vulgar word for “vulva,” or, more generally, the ensemble of her external genital nether areas (the word in Japanese is pronounced mahn-ko). Her “man-boat,” pictured above, is thus a kayak with one part modeled on a representation of her vulva (her English translator translates this word as “pussy,” perhaps in tribute to the feminist art activist group Pussy Riot, or perhaps simply to claim ownership of the “dirty” word). Rokudenashiko claims this boat is a work of art rather than a pornographic image, a creative object that interprets but departs from reality because it lacks realist details such as hair, and is thus not a reproduction that can be judged obscene on the basis of verisimilitude. The term “art” is important in a legal sense because realism is typically judged as being closer to obscenity. Still, the word “manko” itself is controversial and has the signifying power of undiluted reality despite its rather blurry, personal, and idiosyncratic definition for each person. The word is rarely printed in Japanese without fuseji, marks that block out characters to obscure their meaning.

While print censorship literally blocks out parts that represent the female body, Rokudenashiko’s art has drawn attention to the fixation on defining sexuality via one body part by developing an entire aesthetic out of the modular unit of the manko and its plastic boundaries. She uses the manko as a surface, ground, and platform for plastic arts and reconnects this blurrily defined body part to other processes by which women’s bodies are valued. Rokudenashiko makes the process of prototyping the centerpiece of both her creative work and the basis of her representation of the legal system in her manga and a range of other media forms. By challenging the idea that a woman’s body is a medium for promoting national economic growth using artistic forms that rely on digital materialities, she extends the feminist critiques of women’s relation to property that began in the 1970s.

Contexts: Materials and Fighting Words

Rokudenashiko was indicted for three separate counts of violating Article 175 of the criminal code, the main basis for regulating obscenity in postwar Japan. Her boat, pictured above, is a product of the most exuberant element of her art—modeling parts of her sculptures on her own vulva. Rokudenashiko makes art in character, sculptures that are accompanied by extensive textual apparatuses that contextualize modular elements of the story. For example, the manko theme reappears in her manga, as well as in her figures and stickers. Her aim is to not only critique but defamiliarize or render impossible the fetishization of women’s bodies that both reduces the freedom of their own expression and which accrues a different value than, in contrast, fetishized male organs and the powers they underwrite. While visitors flock to phallus festivals celebrated by city fathers and judges as “tradition” and “folkloric tradition,” bringing sought-after tourist dollars to rural areas, the art lovers who seek out Rokudenashiko’s work are testimony of its “social danger,” which is prosecutable under Article 175.(10) A two-part exhibition of shunga, Edo-period erotic art, was held at the Eisei Bunko Museum in 2015. Many male and female bodies were ravished and lavished with erotic attention and graphically drawn sexual organs that are arguably more provocative than the vulva of Rokudenashiko’s art.

The provocation and ultimately the cultural work of this project lies in Rokudenashiko’s treatment of her own body as a digital prototype that can be dematerialized into a mass of code, exchanged, transformed, and customized in myriad open-ended directions by users in their own time, in their own place. Rokudenashiko’s works—whether 3-D kayak, figure, handheld sculpture, or sticker—are all portable and available to be customized in their possessor’s settings. While Rokudenashiko labors, she does not present herself as a worker. She appears publicly in character; it is only newspaper scolds and law enforcement officers who use her legal name to define her as a public figure. She wears a wig, uses her pen name, and has a militantly cheerful attitude. We can read Rokudenashiko’s use of the manko and her whimsical character persona as a meditation on what it means to take the female body out of an economy and reshape it to meet more personal (or even irrelevant or whimsical) needs with the same materials available to policy makers, who use them for productivity and nationalism.

Rokudenashiko first established herself as a manga artist and then as a peripheral member of the art scene. Sculptures whose making she documented in her first published stand-alone manga in 2012 attracted the ire of law enforcement and made her a major figure in the media. Her plastic sculptures have served as a lightning rod for discussions of media representation of female sexuality far beyond the world of art and craft. Further, her contribution to media theory comes most forcefully through practice: it is self-authorized through experience rather than anchored in the almost exclusively male pantheon of conceptually oriented media critics who work in the category of ‘criticism’ (hihyō). Rather than analyzing the approach in which a subject stands outside a system (such as modernity, Frenchness, the self) and analyzes it as a set of externalities, Rokudenashiko is planted firmly in that system as it moves dynamically around and through her, giving her the very means to make things. Her works reference less these groundings and more the possibility of generating new works, new readings, and, accordingly, new articulations of social formations.

Rokudenashiko’s media persona depends on her work and her character being taken lightly, an approach that staves off automatic resistance by appearing benignly humorous or playful as opposed to agonistic. Early in the legal struggle, she distanced herself both from mass politics and, ironically, from feminism, when she put the anger of the age of protests behind her. As we see in the manga What Is Obscenity?, this anger also manifests itself in angry men who lash out at the Rokudenashiko character for daring to take artistic license with their object of sexual desire. However personally fueled by anger to turn the tables Rokudenashiko may be, in terms of artistic process she says, “I see myself as an artist who turns anger into smiles through manga and art. I’m often called a feminist, but the word doesn’t really capture me.… I don’t intend to fight anger through demonstrations or rallies, I’d rather express myself through art and make people smile” (にこにこする niko niko suru).(11)

These “demonstrations or rallies” are shorthand for a series of sometimes violent protests that took place in the 1960s and 1970s contesting U.S. military presence, the reversion of Okinawa, and the eminent domain takeover of farmland for the Narita airport, among other struggles. Those uninformed about Japanese media history of the last ten years may interpret Rokudenashiko’s statement as an insouciant step away from such mass politics into a glib realm of kitsch that, like many Cool Japan products, seems out of touch with lived reality or the kind of cultural work that art can do. These people would be wrong. While Rokudenashiko may disavow the term “feminism,” or give it more fluid definitions than is customary among academics, we should note that she uses the word “smile” strategically with awareness of its media context and its gendering. She is able to remain on point with her messaging and at the same time appear playfully non-allied to a party in her quest for a level playing field for the female body.

Rokudenashiko’s rhetoric taps into interfaces with immense popular appeal and stands apart from the angry male revolutionary figure whose exhaustion has prompted many to seek alternate emotional grounds for galvanizing popular movements. The verb for smiling, niko niko suru, is a homonym for the name of one of the most popular media platforms in millennial Japan.(12) Nico nico dōga (ニコニコ動画 smiling moving images) allows users to upload their comments to video files so that they can be played back simultaneously while additional users comment in real time on the right. Rokudenashiko introduced her man-boat project on this platform, much to the amusement of its users. Most commentators giggled and made liberal use of x, a mock-fuseji letter, and w, indicating laughter, making fun of the practice of censorship while delighting in using the word “manko.”(13)

Naming her mission in terms of a “smile” does not refer to happiness or hospitality (“Have a Coke and a smile!”) but instead locates Rokudenashiko within a style of media performance that emphasizes user-generated content and draws attention to the user-object relation as it exists in a process of making, including value making. Niko Niko is also the name of a tech/IT think tank, the Niko Niko Beta Working Group (学会 gakkai). Niko Niko Beta sponsors large symposia at which members present their gadgets and new tech experiments, many in beta mode, not fully formed and still in the process of modeling, testing, and troubleshooting. 110,000 people attended the first conference in 2012.(14) The working group is composed of academics, fringe intellectuals, tech researchers, and entrepreneurs. All of its projects rely on user-generated research.(15) Given this connection to high tech, Rokudenashiko’s citation of “smile” when describing her mandate situates her in the thick of maker culture: DIY culture that emphasizes experiments in technology that occur in irreverent ways.(16)

As a freelancer who has hustled at multiple part-time jobs while making art as a hobby (趣味 shumi), Rokudenashiko is part of this class of user-creators. What makes her work distinct from many Niko Niko Beta projects is the close link it retains to her body as its source; differentiating her is her use of amateur craft styles as well as high-tech tools while the market role of the work’s prototype is untested.(17) Many forms of applied knowledge prototyped at Niko Niko Beta, including the man-boat, fall into the category of what I call modular aesthetics. Modular aesthetics is a term with broad application that encompasses a tendency in Japanese cultural forms. Modular objects—which we can call modular aesthetics when they work as art objects—refers broadly to media objects that follow a tendency in Japanese cultural forms to serialize (as in the case of modern fiction), link (in the case of video games or manga), or translate across media platforms (in the case of media mix products) such that story or object parts can recombine, reproduce, or innovate story worlds while extending their reach and interconnections.(18) The other feature of modularity is its ability to detach and reattach, due to a set of standards that are technical as distinct from textual: like light bulbs that work in all sockets with the same wattage, modular aesthetics plug and play in any media environment with the same standards. Use of modular aesthetics in general proliferated with mass production (tracks on a record), amplified with figures and personal electronics (like the Walkman), and overflowed in the digital era (software plug-ins).

Modularity

Modularity as a design discourse was coined by architect Arthur Bemis in the 1930s and appeared in the fields of architecture and the construction of electronic computers in the 1950s and 1960s, according to information historian Andrew J. Russell—but it really took off in the 1970s. In the architectural field, modular practice sprung up “within the mid-century American housing and building industries.”(19) The idea of modular replaceable elements featured similarly in the design and construction of projects by Metabolist architects active in Japan from about 1960. Modularity was especially strong in the works of KIKUTAKE Kiyonori (1928–2011) and KUROKAWA Kishō (1934–2007). Kikutake saw wooden buildings as exemplary because their structural system allowed the “possibility of dismantling and reassembling” standard components to compose a “system of replaceability” that could be adapted to various scales throughout a city.(20) Kurokawa, in turn, was the pioneer of the affordable capsule hotel as well as more avant-garde buildings such as the Nakagin Capsule Tower, built in Tokyo in 1972. In the computer field, modularity helped to equilibrate traffic to make networks transmit information smoothly and evenly, and in the industrial literature, modularity is associated with order and control. But when we transfer the concept of distribution to Rokudenashiko’s sphere of speculative design and social formations, the equilibrium that is operationalized here aims to level beliefs, practices, and desires vis-à-vis the sexualized body.

Rokudenashiko’s works all stress a connection to processes of making in the realm of modular materiality and use both retro forms such as dioramas and hand drawing as well as postdigital forms such as 3-D printing and scanning. While modularity is by no means restricted to Japanese cultural forms, Japanese makers, from auto makers to craft makers, tend to think about design objects as well as narrative arcs and make plugging, playing, and translating conceptual issues important over and above technical issues. Characters also exist in modular form, as with artist MURAKAMI Takashi’s DOB character. Dubbed Murakami’s most “ubiquitous and enduring character” by WIRED magazine, DOB appears in paintings and installations in many iterations of color, size, and, especially, setting.(21) Rokudenashiko’s keen focus on the content of her module, however, singles her out from the pack of analysts who treat technical or infrastructure elements, or create characters but deprioritize the substance of their content.

Modular aesthetics can be operationalized by using media machines as common as any convenience store copy machine. In the summer of 2015, a series of visible protests against modifying the constitution used the network of these ubiquitous stores to distribute a prominent antiwar poster. A Japan Times article notes, “The poster features characters originally written in a calligraphic style by haiku poet KANEKO Tota. It can be printed from multifunction photocopiers with Internet connections at convenience stores nationwide. To access the data, copier users need a code distributed by activists on websites, Twitter and Facebook.”(22) There is nothing technologically determined about the use of modularity in design; in fact, using that means of production in similarly distributed ways has allowed makers to use industrial standards to challenge and customize cultural and political norms. Customizing, in the case of Rokudenashiko’s kayak, follows through the process of speculative design to register an awareness of the standards of gender norms at the same time as it distributes a customized and transformed vision of prototyped bodies that build but depart from those norms.

The 3-D printer, to whose wonders Niko Niko Beta introduced Rokudenashiko, is modular in many ways. It is modular at the level of the data that it uses (it dematerializes a given design into component parts of 1’s and 0’s).(23) Then, it is modular because it makes parts that have to be assembled with other parts to make the object. And finally, it is modular because the same set of coding standards ensures that however personal Rokudenashiko’s body was, it can be scanned, designed, and printed so that it becomes part of multiple and innumerable kayaks that fit the same design standards. In other words, the vulva attachment could hypothetically fit any of a number of ready-made store-bought kayaks. The link to property is especially key to the third category of modular design: Rokudenashiko retains the original mold, so while it may be technically possible to reverse engineer the kayak part, retaining the mold and the data allows Rokudenashiko to technically allow reproducibility while also prioritizing access to the information to those who have donated to her cause. As in many fan cultures, a tacit trust is assumed between the artist and the funder/fan who will customize the data in his/her own form.

Niko Niko Beta provided Rokudenashiko’s modular aesthetics with a bridge to out-of-reach R&D resources such as the printer.(24) The artist credits Niko Niko Beta with changing her aesthetic, which had had an “ero-guro” look, an aesthetic deriving from the pulp press in prewar Japan and known for its erotic, perverse, and decadent genre stories.(25) When Rokudenashiko states that the 3-D printer was a conduit to something more “pop” and “high-tech,” she retains the link to mass culture through which pop art takes its materials but empties it of its perversity. I take “high-tech” to mean made with costly electronic machines with high-level software. With this move, Rokudenashiko both takes the manko out of the field of a recognized genre of erotics and estranges it so that we see it as just another set of potential materials. We should thus think of her cheerful “smile” as less an act of feminine hospitality and, like her manko itself, more a plug into the world of high-tech maker culture with a feminist twist.

Indiscreet Rules

One of the mainstays of the women’s lib movement (in Japanese, ūman ribu, typically known as ribu) that emerged in the 1970s was a sustained critique of how not only laws but also labor, domestic, and erotic practices collaborated to situate women as objects in a system of property relations that transferred women as assets between men, while using their labor as a conduit to affirm these relationships of patriarchy.(26) Mass media and the culture industry were not exempt from this critique. Rokudenashiko’s works draw on parts of this history, such as personal liberation and making life experience the grounds for liberation. This section analyzes the story of Rokudenashiko’s first full-length manga to show how it provided a basis for two key aspects of her work: modularity and process.

The story of how the man-boat set sail is rooted in the aesthetics and industry of manga. After graduating from college in Tokyo, Rokudenashiko’s career in the manga industry began in the genre of ‘experiential reportage’ (体験ルポ taiken rupo), or reality manga. In 1998, she won a new artist award from big-three publisher Kōdansha’s women’s manga Kiss. The story was a love comedy about a “sort of stalker-like” character modeled on the artist herself who worked in a real estate agency. Despite the initial fast-track entrance into the industry, Rokudenashiko found that the prize only meant an entrée to further competitions, and even when a work finally was selected, if it did not get good results in reader surveys, it would be pulled. The momentum faltered, and Rokudenashiko sought work at a publisher that specialized in experiential reportage. In this stint, which provided the basis for Rokudenashiko’s sculptural work, life experience became a source material for work.

Reportage in general is a genre that emerged in the proletarian literature movement and refers still to fact-finding missions that reveal obscure or hidden information to a larger public. Experiential reportage mixes the fact-finding mandate of earlier reportage with the expressive rhetorics of first-person fiction—“literally putting real experiences into manga,” as Rokudenashiko puts it.(27) The sub-genre of experiential reportage emerged in the late 1970s as fieldwork-oriented reporting by devotees, as opposed to scholars published in manga or para-academic paperbacks called shinsho (new books). Early examples of the genre featured life experiences of labor, while more recent examples focus on how people have navigated the systems of life such as elder care (“Social Welfare and Elder Care in Japan”) or more frequently gambling and the sexual underworld (“Sex with Women from Fifty-One Countries: Diary of a Man Who ‘Conquered’ 5000!”).(28) Experiential reportage is documentary in its depiction of real events, but focalizes the story through a writer’s eyes, body, and pen, and is often organized in modular case-study form. In Rokudenashiko’s case, the first-person voice compounds the fact-finding impulse of reportage with the highly interpretive visual and story conventions of shōjo manga. The result is a first-person story buttressed by empirical details that contribute a truth effect to the highly personal vision and track a process while the outcome often remains suspended.

The processing of modular elements frames this tale conceptually because shōjo are frequently represented in mainstream media as raw materials that will ultimately be brought into a sexual marketplace after a phase of consumerist polishing. This pending state was described in a 1982 article by literary historian HONDA Masuko, who was among the first to establish ‘girls’ culture’ as an independent field of study. Her essay used the key metaphor of the cocoon to explain the ontology of the shōjo: “There comes a day when a girl realizes she is a shōjo, a day she also learns she can never be a boy, a shōnen. From that time it is as if she spins a small cocoon around herself wherein to slumber and dream as a pupa, consciously separating herself from the outer world. Here, she lives life to her own time, a time that can never be lost.”(29) This cocoon-like ability to put reality on pause and develop a vivid interior life is the hallmark of shōjo manga, one that Rokudenashiko puts to different ends than either opting out of the system or entering the marketplace leading to marriage.

Rokudenashiko’s big break came with a manga that mixed these two genres by putting life on pause to figure out her alienated and vexing relationship with her own sexual body. Decoman (2012) is an ambitious tale of experiential reportage that is structured as seven fairy tales, modular chapters, in the mode of shōjo manga. Processing is also an important alternative to both the technocracy that disadvantages female cultural producers and to the act of revolution and conflagration pursued by male revolutionaries. These modular aesthetics work to shift and show the shift of relations between women-as-things and the world of things in general. While shōjo texts often introduce technological processes into the everyday through subplots that involve magic, these projects articulate processes that are replicable in the nontextual world. They are geared toward questions about feminine invisibility and how to disrupt that invisibility.

Decoman pursues the question of visibility as a kind of kunstler-manga. It documents Rokudenashiko’s artistic formation vis-à-vis a series of anxieties she represents about her own body and what she thought of as its abnormalities, sparked by a beautiful older sister, a too-blunt family and a series of careless lovers and eager surgeons. (In her later manga What Is Obscenity? the Rokudenashiko character explains that her editor at the time encouraged her, in order to ramp up sales, to depict feelings of inadequacy that inspired her to get plastic surgery on her labia. The frame story in the later manga distances Rokudenashiko from feelings of inadequacy and plastic surgery-related complex to cast the art as less sensational and more speculative.) In Decoman’s story of artistic formation, the Rokudenashiko character comes to the conclusion that many other women labor under the same internalized anxieties, and starts making art and giving art workshops on making decorated manko art (see fig. 10.3).

![[Figure 3: TEXT MISSING]](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig3.jpg)

The sculptural form Rokudenashiko returns to is the decorated manko, or ‘decoman‘ diorama, of which there are two kinds. The ‘deco’ part is a process that involves Rokudenashiko taking an impression of her vulva on a disposable sushi tray with the same kind of alginate molding that dentists use to make casts for false teeth and pouring a cast of the mold. Then the solidified object serves as a surface for various miniature decorations. The result is that the manko becomes the setting for a world, like a little landscape dollhouse with people caught in motion.(30)

![[Figure 4: TEXT MISSING]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig4-1024x777.jpg)

![[Figure 5: TEXT MISSING]](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig5.jpg)

In addition to the dioramas depicted in Decoman, Rokudenashiko began to devise new formats for her manko art, of which two are most key: figures and the man-boat.

![[Figure 6: TEXT MISSING]](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig6.jpg)

In summer of 2015, the kayak, despite its modular programming, distribution, and possible reproduction, was beached—confiscated and held as evidence. Its existence as data and as boat begs the question of how processing affects the legal status of an object: what is the status of a set of manipulable data? An Asahi shinbun article from July 15 notes that Rokudenashiko was charged with sending a thirty-year-old male company employee in Kagawa prefecture the data from her “female sexual organ/s” (女性器) that he could reproduce (復元) as a third object.(33) As a later Asahi article pointed out, data has a materiality that does not restrict it to “reproducing” something.(34) For example, a faculty member of Tokyo University of the Arts used data compiled from weather info collected in Tokyo in one day in 2014 and formed it into the shape of a big, squat vase. He demonstrated that the processed product bears no resemblance to its place of origin or its processing software, nor is it supposed to.

Traversing media with the special 3-D software demonstrates how, as Johanna Drucker notes, “the stripping away of material information when a document is stored in binary form” of zeros and ones “is not a move from material to immaterial form, but from one material condition to another.”(35) Rokudenashiko’s claim hinges on this point: that data from her body can represent it but are not it as such. To think of data as a medium that requires processes and shaping to become an object is a very empowering thing. What the kayak enables via digital materiality it loses in authenticity. No longer does the kayak retain an indexical link to Rokudenashiko’s body. As of 2016, although the manipulation of data into a new material form would seem to anchor it in the realm of art, the legal status of data is undecided, as is the status of a work of art in a digital process.

Despite the manifest cuteness, the emotion that overwhelmingly appears in Rokudenashiko’s descriptions of reactions to her art—very modestly displayed in small galleries at prices that even small collectors could find reasonable—is rage. The story of this little woman in a boat leapt off the page and into everyday life in 2014. On June 18, 2013, Rokudenashiko started a campaign on the crowd-funding site Campfire to seek funding to build an attachment to a kayak modeled on her vulva. The campaign reached 194 percent of its goal—a total of one hundred million yen—on September 6, with contributions from 125 people. In July 2014, at 9:00 on a holiday morning, Rokudenashiko was arrested for an alleged violation of Article 175 of the criminal code for distributing obscene data (ワイセツ電磁記録媒体頒布罪) in March of the same year. Rokudenashiko had emailed a link to the 3-D scanner data of her vulva to people who had supported her campaign at the level of three thousand yen and above (sixty-five people were eligible), and gave a CD-ROM with the data to seventeen others.(36) Rokudenashiko was released after a week, after an online petition at Change.org registered more than 21,000 signatures. “I turned the whole ordeal into a manga satirizing the police. That hurt their pride, so they trumped up some charges and arrested me in December.”(37)

After this first arrest, the press portrayed Rokudenashiko as angry, and something of an imposter as a “so-called artist” (自称芸術作家), a label she embraced proudly in her 2015 manga What Is Obscenity? by using it as the subhead for the eighteen chapters that narrate both her artistic formation and her run-ins with police. The initial press followed the line of police press releases closely.(38) And indeed, as we saw above, Rokudenashiko’s early manga show her as angry, taken aback, frustrated, and outraged. In this, her affect coincides with a classic oppositional mode of protest, often gendered male in Japanese leftist politics. After the student movement dwindled in the late 1960s, many male activists suffered melancholia or political fatigue. Following that portrayal, Rokudenashiko made a change in her camera demeanor and in her writing to use emotional directness less, and emotional processing more. She began to use humor in a way that did not stress the absurdity—although her target, the law and the state, could be made to seem absurd, and therefore belonging to a dimension apart from reality. She became militantly cute, an approach I explore later in this section.

On December 3, 2014 Rokudenashiko was arrested for a second time at an exhibition of her works—a collection of dioramas—in the window of a gallery in a sex shop owned by KITAHARA Minori.(39) This arrest became the subject of Rokudenashiko’s second book, What Is Obscenity?, a memoir of her time in jail.(40) What Is Obscenity? ditches the shōjo narrative structure to narrate the experience leading to Rokudenashiko’s arrest, confinement, and continued activities after her release. The period of confined waiting often featured in shōjo stories must have seemed difficult to maintain as a fantasy after being handcuffed in a locked room with five other people over an eight-hour period in mid-July while waiting for trial. The book features a number of stand-alone essays and taidans with male leftists, and made way for a slightly new version of the character.

Cute Strategies, Close Readings

After Rokudenashiko’s media baptism, her new camera demeanor and conspicuous use of humor had two prongs: cuteness and ubiquity. Rokudenashiko’s strategy of cuteness differs almost 180 degrees from the typical revolutionary’s method of leadership standing outside of the masses or taking an avant-garde role that precedes them. Her stance indeed draws on outrage: a classic emotion that sparks a narrative of wrong, critique, and redress to announce a position of strength and conviction typically based on ideals or reason. At the same time, her stance rings supremely cute, an aesthetic that solicits protection but can also engender aggression, and exists in a commodity-based world of exchange. It calls on intimacy, feelings of belonging and play that follow from the attachment to personal-sized modular objects. Cute, writes Sianne Ngai, taps into a “spectrum of feelings, ranging from tenderness to aggression, that we harbor toward ostensibly subordinate and unthreatening commodities.”(41) This spectrum is evident in users’ reactions, which range from the devoted standing in line to solicit her autograph to the outsized police reaction of confiscating works of art that any art lover actually has to make a great deal of effort to track down.

![[Figure 7: TEXT MISSING]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/mcknight_fig7-1024x1005.jpg)

At this point it is worth setting Rokudenashiko’s affect and stance in context of the women’s liberation movement indigenous to Japan known as ūman ribu (women’s liberation, usually known as ribu). Ribu activists who emerged in the waning days of the student movement critiqued the fact that women were legally framed as objects, not subjects, by the family system (家制度 ie seido) that regulated structures of inheritance. But the critique went beyond literal realms of inheritance to touch on social and cultural forms that underwrote women’s status as object. Sexuality was included in this equation; activists opposed the default of marriage and railed against the cult of virginity.(44) Ideas and debates were often spelled out in mini-komi (mini-communications or small-circulation periodicals, alternative print and image media production-distribution systems in contrast to large-circulation masu-komi media) communicators. Writing in retrospect about the student movement, the ribu activists and writers who published in ribu journals and mini-komi provided critiques of the way in which sexual and gender politics were sidestepped as mass protest escalated in violence. Mini-komi emerged to confront this system of property relations and to enable liberation through critique and the creative acts of other alternatives as personal life was imagined to empty into politics. Although it is based in digital materiality and plastic arts rather than print culture, Rokudenashiko’s use of modular aesthetics allows for the distribution of information that facilitates building social movements in ways that recall the cultural work of mini-komi.

SETSU Shigematsu summarizes IIJIMA Akiko’s well-known position paper from 1970, one that “cleared a politico-theoretical space for ribu” as an indictment of the fact that “the ‘laboring class,’ ‘labor unions,’ and ‘theory’ were men’s domains,” and went so far as to declare that “theory was a man.”(45) While this claim is easy to discard as hyperbolic if taken literally, it is readily understood to mean that theory has worked in myriad ways to reinforce rather than dismantle patriarchal structures. The same is true of critics, practitioners of theory in commercial, academic, and para-academic areas of the culture industry. One venue that included the culture industries and saw creators as critics was the journal Onna erosu (Woman/eros). Onna erosu began publication in 1973. Its first issues featured lacerating critiques of patriarchal systems, one of which was media institutions, up to and including independent film productions. For instance, one contributor penned an essay about her disappointment with the heroine of a successful porno movie series called The Young Wife: Confessions (幼妻:告白 Osana dzuma: kokuhaku) directed by NISHIMURA Shogorō and starring KATAGIRI Yūko. The series depicts the heroine as “embracing [!] the dream of marriage,” but she is raped by the older brother of her fiancé. Initially protesting, she gives way. The older brother gives her some money, and she says resignedly, “I knew that things would end up this way.” The Onna erosu writer, in a column called “The Female Sharpshooter” (女狙撃兵 “Onna sogeki-hei”), writes that the film disappoints because it does not offer a reality other than the patriarchal one that currently exists, but rather affirms it while posing as progressive:

Film is supposed to have the quality of transporting the spectator to “another reality.” It is a medium where it is possible to present reality, anticipating it, and anticipate what might come of it. Among which, “porno” is able to be so far ahead of its time that it causes scandals in court. But because only this kind of “pitiful woman” is the only one featured, in the end porno film is not able to set foot out of its dark little self-satisfied castle and fly the flag of progressivism.(46)

At the time porno movies were embattled with censors. There were obscenity trials, but directors and staff also reveled in an antiestablishment antiauthoritarian stance. Kishida ends her article in disbelief. About the disconnect between roman porno’s bout for legitimacy in the courts and the conventional passive fate of this movie’s heroine: “You call that a struggle?!?” (闘争 tōsō). Kishida’s main objection is that, in the film, the heroine is “cast upon the flow of fate,” both sacrificed and numbly meek about her fate, whereas many women in this era actually “make fate and move forward.”

Like the ūman ribu activists, Rokudenashiko’s stance of militant cheer and “making” is an alternative to the sacrificial maiden role to which women were frequently consigned in 1960s mass movements.(47) In the end, both Rokudenashiko and ribu activists refuse to delink the female body from other systems. But unlike ribu activists, Rokudenashiko does not look directly to the erotic dimension of sexuality as her domain, although one could certainly introduce the manko into a new discourse of sex, once its fetish value has been leveled. Nor does Rokudenashiko demonize particular men or male characters. Rather than raising the ideal of freedom via sex, she chooses to deflate a word that represents something so ideal as to be talismanic: manko. This effort resembles the precision of ribu activists when they shifted the word for woman from fujin (wife) or josei (woman) to another slightly more salacious and lower-class-sounding term, onna, as a marker of departure from conventional gender norms. But Rokudenashiko’s strategy inverts this: the very syllable of the word de-stigmatized is actually built in everywhere. Of course, the words are standing for the body part that, if it is not exactly everywhere, is one among many parts of half the world’s population.

The Japanese syllable man can be found everywhere, in every walk of life, from man-boat, and manhole, to one-man (ワンマン運転) driven train, mandala, even manga.(48) When you consider how the syllable man is built into the Japanese language, it quickly becomes clear that language as a whole would be poorer without it. But at the same time, the arbitrariness of judging manko as obscene while mandala are revered clarifies how much human projection is committed to fetishizing this one modular organ. These strategies of ubiquity and cuteness embrace if not celebrate contemporary consumer capitalism, within which Rokudenashiko is very much located. If in consumer culture and its close relative, media culture, we are saturated at all times with overflows of information, Rokudenashiko’s strategy is to cheerfully and polemically point out that ‘man’ is a syllable that has always been with us and whose absence would cause significant semiotic damage not only to that syllable but to others attached to it. At a roundtable and book signing in May 2015, Rokudenashiko laughed gleefully at the way the translator at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club mispronounced her signature work as ‘man’, adding a second-language opinion to her claim of ubiquitous male privilege. ‘Man’ is present, it is ubiquitous, and by deleting it, we delete significant parts of reality while making it a source of abjection consigned to its secret, shameful, and hidden place.

Angry Reactions

An acrimonious Twitter exchange in July 2015 saw Rokudenashiko being castigated for incorrect use of the label ‘feminist’. The discussion between Rokudenashiko’s more freewheeling use of the term and her critics’ literal criteria is ongoing. We might wonder why police officials as well as some feminists react so strongly. We could guess at reasons, both art historical and political. On the art-historical front, these dioramas seem to be sui generis—self-authorized. In early works before the arrests, Rokudenashiko rarely made reference to earlier artists.(49) This tendency distinguished her from the ribu generation as well as from its academic allies. Sociologist and critic of feminine wartime collaboration UENO Chizuko’s stand-alone first essay collection, for instance, Women at Play (女遊び Onna asobi), used modular elements from Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party in its book design and in its structure.(50) Chicago’s installation is epic in scale and in labor. It is a work of media archaeology that retrieves underknown women’s biographies, concretizes a design form for each, and places them in a stylized communal setting as a metaphor for a convivial conversation between women across spaces and times. Dinner Party incorporates rather than proliferates its model and variations, as does Rokudenashiko’s work. Because of this sui generis presentation, the interpretive weight of Rokudenashiko’s work was likely placed fully on her. What is compelling about her works is that they do not attempt to hide their source, but they do not flaunt it either: they use it as just another material—unlike Ueno and ribu, Rokudenashiko’s work directly refers to no past, and sees the manko as another substance, not an ideal; but like Ueno and ribu, it seeks to use this modular body part to create the ground for a better, or more potential-filled, future.

Rather than monuments, Rokudenashiko’s works are miniature. The handheld dioramas invite intimacy, and their small size demands close scrutiny to read the arrangement in any way; the figures and dioramas are cryptic in the emotions they invite. Interrupting with the body of the artist seems important in the way people interpret Rokudenashiko’s work. Realizing that the mass-produced object is indexically related to a specific body causes shock and repulsion—or amusement. That these fantasies should be made concrete in a kitsch form, and not very well groomed, goes against the disciplinary rules of cosmetics and grooming culture that regulate many women’s relations to their bodies and that surface in Rodukenashiko’s early manga.(51) The nonchalance with which soldiers lie in wait for the enemy in foxholes dotting a manko battlefield, or the schoolgirls romp up a manko hill to chapel might strike someone as inappropriate, if they were interested in female bodies as either pure functionality, or pure erotic fetish “belonging” to them. Far from being erotic (the subject of sexualized fetishism never surfaces, Rokudenashiko’s works are very much seen as killjoys), they are a kind of medium.(52)

Coda

Rokudenashiko joins other manga artists who are technically too old to be shōjo yet use the received conventions of suspended time and interior expression to dilate on a particular issue. A sense of personal time detached from chronological time lends itself to the genre of the fairy tale. These formal dimensions reinforce a set of story conventions that privilege yet suspend the happy ending—a temporal dynamic of suspension I return to vis-à-vis Abenomics in the coda to this essay.

In 2016, the role of women in a national context is driven by Abenomics—the policy directives of prime minister Abe Shinzō’s administration that aim to stabilize the economy as well as increase the birth rate. Forty percent of the Japanese work force does contract labor, and frugality and craft have surged in popularity. The labor situation for women is asymmetrically bleak, with female workers occupying disproportionately low-paying or temporary jobs with yet less chance for advancement or security than male workers. Abenomics is a gray area whose policy ideals have been articulated, even if the concrete results are new or not in place. In the interim, women have started to press for equal wages, but without using the label ‘feminist.’ These women are of the generation that grew up with the narrative of the shōjo manga, whose key metaphor was the cocoon and whose key climax was the happy ending. Rokudenashiko is one of these women who grew up with suspended creation as an ideal, but used that cocoon moment in her work to dream and make rather than to sleep.

Rokudenashiko’s navigation down the Tamagawa River, avoiding the rocky shoals of obscenity and delivering its content to its destination, resembles nothing less than the voyage of Norbert Wiener’s storied cybernaut.(53) In Wiener’s account of cybernetics, the system requires a steersman who is responsible for the self-reflexive check on communication processes and who ensures that the system continues to function while incorporating input from outside the system, and at the same time stays on course ethically. Rokudenashiko channels and updates the critique of property by claiming her body as an object that she steers and navigates in a dynamic world that the river is, stands for, and connects. Who is to govern sexual representation is precisely the question at stake.

This river, like many ecological objects, including media ecologies, is no longer a closed system that can be isolated in analysis or lived experience from a larger ecology and the human effects on it. While Rokudenashiko reconnects the art object to a prominent natural location, she does not connect it to wild feminine nature. Her boat launch suggests a bawdy and unabashedly suburban version of Gaia in which a human-object encounter ends up taking the artist back to a primal source of life, water, at the same time that it connects her to the thoroughfares of the nation and world, not to mention mass-produced products and digital communications. The works challenge and redraw ideas of ownership and property—typical concerns of ūman ribu, Japan’s 1970s feminist liberation movement.(54) They do so by anticipating and rerouting what consumers, male or female, expect to receive when they purchase a small and affordable, even cheap, art piece. Rokudenashiko’s work is celebratory not because it builds a canon, or even because it sees knowledge as enlightenment—though it definitely has its pedagogical side. These enthusiasts merely reinforce the point Rokudenashiko’s manko art brings home over and over again about this vessel: it is already there, it is a free channel, its boundaries are fluid, and as a taxpayer (or owner), it already belongs to you. Own it.

Thanks to Jean-François Blanchette, Phil Brown, Kirsten Cather, Laura Forlano, Ian Lynam, Namiko Kunimoto, Lisa Onaga, and the editors of this volume.

Anne McKnight was trained in comparative literature, and is a professor of Comparative Culture at Shirayuri University in Tokyo. Specialties are modern/contemporary Japanese literature, film and food culture. Recent publications in English include Nakagami, Japan (Minnesota, 2011), an essay on feminism and soft-core Japanese porn cinema (camera obscura, 2012) and a translation of Japan’s first robot story (Expanded Editions, 2015). Coming up is a translation of a memoir-ish book by director Kurosawa Akira.

This article was originally published as a chapter in Media Theory in Japan, edited by Alexander Zahlten and Marc Steinberg, published by Duke University Press in 2017. We thank Duke for permission to republish it here.

Works Cited

(1) The Tamagawa River boat launch draws on histories of freedom, expression, and resourcefulness that characterize riverbanks as a space. Like many such spaces in Japan, the Tamagawa’s banks have a rich tradition of serving as a public space for physical and artistic activities. Sports teams have playing fields there, while the grassy open spaces also offer a refuge for musicians and others who cannot make their noise at home. Historically, rivers were home to social outcasts called kawaramono, river dwellers who later specialized in garden design and became artistic advisors to the ruling government.

(2) See “Gender, Genitor, Genitalia—Rokudenahsiko sapōto-ten,” Campfire, accessed July 12, 2015, http://camp-fire.jp/projects/view/2809.

(3) Mark Frauenfelder, “Japanese Artist Goes on Trial over ‘Vagina Selfies,’” Boing Boing, July 28, 2015, http://boingboing.net/2015/07/28/japanese-artist-goes-on-trial.html; “Who’s Afraid of Vagina Art?,” Broadly, accessed March 1, 2016, https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/topic/rokudenashiko. Rokudenashiko’s name itself is a definite step away from a feminism of virtue that stands outside a system and judges. Rokudenashiko—meaning a “no good” but ultimately harmless woman who is a known or familiar character—comes from the pen name the artist used when writing an experiential reportage about cheating on her husband. The “no good” was clearly a parodic knock on the artist’s own everyday life, and contributes to the rhetoric of honesty about conventional morality that affirms the “true story” quality of her chosen genre.

(4) Jonathan E. Abel, Redacted: The Archives of Censorship in Transwar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). Kirsten Cather, The Art of Censorship in Postwar Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2012). There was one earlier case of public obscenity that featured a woman. ICHIJŌ Sayuri was a celebrated stripper from Osaka who also appeared in KUMASHIRŌ Tatsumi’s roman porno films, including one in which she plays herself doing strip shows and is arrested by the police. Though Ichijō’s media were crime and live performance, like Rokudenashiko, her crime was exposing her genitals. Ichijō was arrested under Article 174, public indecency, and served six months in prison. See Kirsten Cather, “The Politics and Pleasures of Historiographic Porn,” positions: east asia cultures critique 22, no. 4 (2014): 753.

(5) Two examples from different generations of creators are photographer ARAKI Nobuyoshi’s celebrated nudes, which strengthen the indexical relation to reality via their personal tie to the photographer himself, and Murakami Takashi’s 2015–16 exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, The 500 Arhats, which features a drawing of an elephant inspired by Edo-period aesthetics in which the elephant’s fantastical “third eye” is an aestheticized vulva.

(6) Helen Macnaughtan, “Womenomics for Japan: Is the Abe Policy for Gendered Employment Viable in an Era of Precarity?,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, April 5, 2015, http://apjjf.org/2015/13/12/Helen-Macnaughtan/4302.html.

(7) McKenzie Wark, Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene (London: Verso, 2015).

(8) Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (Cambridge, MA: mit Press, 2013), 2–3.

(9) Alan Galey and Stan Ruecker, “How a Prototype Argues,” Literary and Linguistic Computing 25, no. 4 (2010): 406.

(10) “Seiki katadotta sakuhin geijutsu ka waisetsu ka” [Is a decorated sex organ art or obscenity?], Asahi shinbun, December 17, 2014, chōkan edition.

(11) Samantha Allen, “Japan’s ‘Vagina Kayak’ Artist Fights Back against Obscenity Charges—and Misogyny,” Daily Beast, January 13, 2015, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/13/japan-s-vagina-kayak-artist-fights-back-against-obscenity-charges-and-misogyny.html.

(12) Although the spelling differs, the pronunciation of nico and niko is the same. The spelling nico is part of the branding of the online commenting platform and is favored by its users; niko is the standard favored by linguists and dictionaries; and Niko is the preferred spelling of the name of the working group.

(13) “Rokudenashiko ‘Decoman,’” Niconico dōga, accessed June 30, 2015, http://www.nicovideo.jp/watch/sm24004330.

(14) Kōichirō ETO, Niko Niko Gakkai Beta o kenkyūshite mita [I went and studied Niko Niko Beta working group] (Tokyo: Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 2012).

(15) While affiliated with research universities and corporate think tanks, Niko Niko Beta’s organizers are less concerned with institutional authority than most think tanks.

(16) Niko Niko Beta partnered with Maker Faire to hold a conference in Singapore in 2015.

(17) Megumi Igarashi (Rokudenashiko): Art and Obscenity: Did the Japanese Police Go Too Far with Her? (Tokyo: Foreign Correspondents’ Club, Tokyo, 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u35rEg_nTV8.

(18) For a discussion of the “media mix” and pop culture commodity forms, see Marc Steinberg, Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

(19) Andrew L. Russell, “Modularity: An Interdiscplinary History of an Ordering Concept,” Information and Culture 47, no. 3 (2012): 259. For a discussion of how Arthur Bemis’s idea was transposed into Japanese architecture after 1945, see Izumi KUROISHI, “Mathematics for/from Society: The Role of the Module in Modernizing Japanese Architectural Production,” Nexus Network Journal: Architecture and Mathematics 11, no. 2 (2009): 201–16.

(20) Zhongjie Lin, Kenzo Tange and the Metabolist Movement: Urban Utopias of Modern Japan. (New York: Routledge, 2010), 102.

(21) Jeff Howe, “The Two Faces of Takashi Murakami,” WIRED November 1, 2003, http://www.wired.com/2003/11/artist/. Thanks to Namiko Kunimoto for noting the Murakami exhibition.

(22) “United in Outrage, Protesters Printing Anti-Abe Posters in a Nationwide Campaign of Dissent,” Japan Times, accessed February 16, 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/07/19/national/politics-diplomacy/anti-abe-posters-raised-across-nation-protesters-rally-security-bills/#. Published July 19, 2015.

(23) The 3-D printer has changed design processes not only in architectural offices but also in artistic practice. Workspaces such as Fab Café in Tokyo’s Shibuya neighborhood offer the use of facilities and machines such as 3-D printers for hire that struggling artists cannot afford on their own.

(24) Rokudenashiko, Watashi no karada ga waisetsu?!: Onna no soko dake naze tabū [My body is obscene?!: Why is only my lady part taboo?] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2015).

(25) Mark Driscoll, Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan’s Imperialism, 1895–1945 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010). A comparably vulgar scene of the pink film is explored in The Pink Book, an anthology of writings on the “ero-duction” that is very much of this era—grungy, low budget, embedded (enseated?) in its viewing context, and slowly disappearing. KIMATA Kimihiko’s essay taps into an ancestral strand of parody and irreverence whose tributary may be found in Rokudenashiko’s work. Essays by Roland Domenig and Kirsten Cather focus in particular on censorship issues, where Cather also points out that “obscenity” was a positive marketing term for pink films because it referred to a sub-genre. Sharon Hayashi’s essay in the same volume notes WAKAMATSU Kōji licensed his staff to shoot “anything as long as it was anti-authoritarian and anti-establishment” (Sharon Hayashi, “Marquis de Sade Goes to Tokyo,” 284). Markus Nornes, ed., The Pink Book: The Japanese Eroduction and Its Contexts (Ann Arbor, MI: Kinema Club, 2014).

(26) Much crucial work has been done on the intellectual, social, and movement histories and discourses of ribu. In English, see Setsu Shigematsu, Scream from the Shadows: The Women’s Liberation Movement in Japan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012); and Vera C. Mackie, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment, and Sexuality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). Curious readers interested in media are referred to a three-volume set of documents, MIZOGUCHI Akiyo, SAEKI Yōko, and MIKI Sōko, eds., Shiryō Nihon ūman ribu-shi (Tokyo: Shōkadō, 1992). Work on documentary film treats women in new left contexts; see Markus Nornes, Forest of Pressure: Ogawa Shinsuke and Postwar Japanese Documentary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). Many feminist studies of early twentieth-century social and art movements have recently appeared, forming a protohistory of ribu as seen in shōjo and revolutionary cultures, but a synoptic media history of ribu is still a work to come.

(27) Rokudenashiko, Watashi no karada ga waisetsu?!, 117.

(28) YAMAI Kazunori and SAITŌ Yayoi, Taiken rupo: Nihon no kōrei-sha fukushi (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1994). DEMACHI Ryūji, Taiken rupo: Zainichi gaikokujin josei no sekkusu 51-ka kuni: 5000-nin o “seiha” shita otoko no nikki (Tokyo: Kōbunsha, 2011).

(29) Masuko HONDA, “The Genealogy of Hirahira: Liminality and the Girl,” in Girl Reading Girl in Japan, ed. Tomoko AOYAMA and Barbara Hartley (Oxford: Routledge, 2010), 19–37. Media artist Sputniko’s work, based at the MIT Media Lab, has also used the cocoon as a metaphor for shōjo culture. See her 2015 installation, “Tranceflora: Amy’s Glowing Silk,” Sputniko! Official Website, accessed February 22, 2016, http://sputniko.com/2015/04/amyglowingsilk/.

(30) Unlike other recent uses of the term “world,” the decoman sculptures are not part of a larger narrative structure, nor are they translations of or exports to other national discourses. For the former approach, see ŌTSUKA Eiji, Teihon monogatari shōhi-ron [Authoritative edition: On monogatari consumption] (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 2001). For the latter, see Pascale Casanova, The World Republic of Letters, trans. M. B. DeBevoise (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

(31) See Simon Partner, Assembled in Japan: Electrical Goods and the Making of the Japanese Consumer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

(32) See http://www.gankagarou.com/shop.html.

(33) “3-D purintā yō dēta ‘waisetsu-butsu’ hanpu no utagai: Jishō geijutsu-ka taiho, yōgi hinin” [3-D printer data charged with “distribution of obscene item”: Self-professed artist arrested, denies charges], Asahi shinbun, July 15, 2014, chōkan edition.

(34) ŌNISHI Wakato, “Āto to waisetsu—hasama de” [Between art and obscenity], Asahi shinbun, July 23, 2014, chōkan edition.

(35) Cited in J.-F Blanchette. “A Material History of Bits,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 62, no. 6 (2011): 1042–57.

(36) Campfire is restricted to people with Japanese addresses and bank accounts.

(37) Samantha Allen, “Japan’s ‘Vagina Kayak’ Artist Fights Back against Obscenity Charges—and Misogyny,” Daily Beast, January 13, 2015, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/13/japan-s-vagina-kayak-artist-fights-back-against-obscenity-charges-and-misogyny.html. That manga was called Waisetsu-tte nan desuka? and was published by Kinyōbi (for whom Rokudenashiko has written some articles) on April 3, 2015.

(38) SHIBUYA Tomomi, “Sekai no shio: Rokudenashiko taiho ga aburidasu shakai no jinken kankaku” [Winds of the world: Rokudenashiko’s arrest shakes up the perception of human rights], Sekai, no. 860 (2014): 38.

(39) Love Piece Club is open once a week by appointment, and does not allow male visitors. Kitahara is not only a small-business owner, but a visible public intellectual and writer. Her recent published taidans include dialogues with novelist TAKAHASHI Gen’ichirō and academic feminist Ueno Chizoku. Along with sex toys, swimsuits and horoscopes, the store’s website also blogs regularly on issues of concern to women, work, and sex with a focus on the sexual double standard that parallels Rokudenashiko’s.

(40) Rokudenashiko, Waisetsu tte nan desu ka? [What is obscenity?] (Tokyo: Kinyōbi, 2015).

(41) “Zany, Cute, Interesting: Sianne Ngai on Our Aesthetic Categories,” Asian American Writers’ Workshop, accessed June 8, 2015, http://aaww.org/our-aesthetic-categories-zany-cute-interesting/.

(42) As testimony to how powerful a re-alignment this is, I will note that her supporters in English have insisted in translating her work as “vagina” art. It’s not, it’s about the vulva, or the pussy, or—but the word “vagina” has come to be a part of public discourse in much more acceptable ways in the last twenty years due to Eve Ensler’s play The Vagina Monologues. The play was produced both in English and Japanese beginning in 2004, when a Filipina theatre troupe did the first production.

(43) Support MK Boat Project! The World’s First 3-D Scanned Peach on the Beach, accessed June 9, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A5qq4cXoR9w.

(44) For a representative manifesto, see TANAKA Mitsu, “Benjo kara no kaihō” [Liberation from the toilet], Onna erosu, no. 2 (1973): 178–90.

(45) Shigematsu, Scream from the Shadows.

(46) KISHIDA Masao, “Porno eiga no heroinu wa naze furui onna ka?” [Why is the porn movie heroine so old-fashioned?], in “Onna sogeki-hei” [The woman sniper], Onna erosu, no. 1 (1973): 170.

(47) KANBA Michiko was the most frequently cited and mourned of these students. See Chelsea Szendi Schieder, “Two, Three, Many 1960s,” Monthly Review, June 10, 2015, http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2010/schieder150610.html.

(48) Man doesn’t necessarily recall the English word referring to maleness, but it cannot be completely ruled out. A recent movement to encourage men to take a greater role in child raising is called the ikumen movement, from the words for raising children (ikuji) and the English “men.” And the cartoon character Anpanman is, after all, an indeterminately aged male figure with a head made of delicious anpan (bean paste–filled bread).

(49) As the trial dragged on, however, Rokudenashiko and her legal team began to use more examples of internationally-known artists such as Valie Export, Shigeko KUBOTA and Judy Chicago to point out the double standard at work.

(50) Ueno Chizuko, Onna asobi [Women’s play] (Tokyo: Gakuin Shobō, 1988). I should note that Ueno’s book—a New Aka edition—also uses the word “manko” without fuseji. Modular book design took off in the 1980s when the style of New Aka writing started to depend on data points of knowledge to which it linked in footnoted summaries and bibliographies. This mode of citation is linked to broader trends in data visualization, such as the chart (of intellectual movements, tendencies, and relations), and DTP design aesthetics allowed for multiple layers of print and page units without the labor of typesetting.

(51) Article 175 has been especially active in policing “hair nude” or full-frontal nude photography where pubic hair but not genitals is captured. Enforcement of a block on photographing pubic hair started to relax in the 1980s and 1990s, with SHINOYAMA Kishin’s 1991 Water Fruit a benchmark.

(52) In this Rokudenashiko is like the photographer TAKANO Ryūdai, who had an exhibition at the Aichi Prefecture Art Museum from August through September 2014. The photos featured naked and mostly male bodies, and were censored; instead of taking the photos down, the photographer displayed them with the odd-looking curtains.

(53) Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics; Or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (New York: J. Wiley, 1948).

(54) Setsu Shigematsu, “The Japanese Women’s Liberation Movement and the United Red Army,” Feminist Media Studies 12, no. 2 (June 1, 2012): 163–79.