Between the Shritstorms

Kuba Szreder

The opening lines of UBU the King, a political satire published by Alfred Jarry in 1898, are “it happened in Poland, that is to say nowhere.” What sounds like a slightly ironic yet apt jibe at my home country, in which a feeling of political farce is seamlessly connected with the grim reality of a land ravaged by historical tragedies, was rather a factual description of political reality at the end of the 19th century. Jarry wrote his piece when Poland was indeed partitioned between surrounding countries.

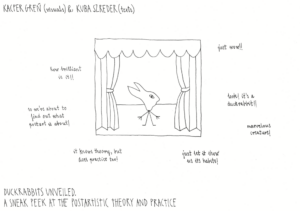

Possibly because of its tongue-in-cheek yet politically grounded tone, I like to reference this quote, most recently in a comic strip Duckrabbits Unveiled. A quick peek at postartistic theory and practice (co-authored with Kacper Greń and published in 2025 together with the Institute for Network Cultures). I typically subvert it, though, saying “it happened in Poland, that is to say everywhere,” as I use it to tell a story of Poland as a UBU country that descends into a farcical yet uncanny version of authoritarianism. A representative of a tendency that unfolds everywhere.

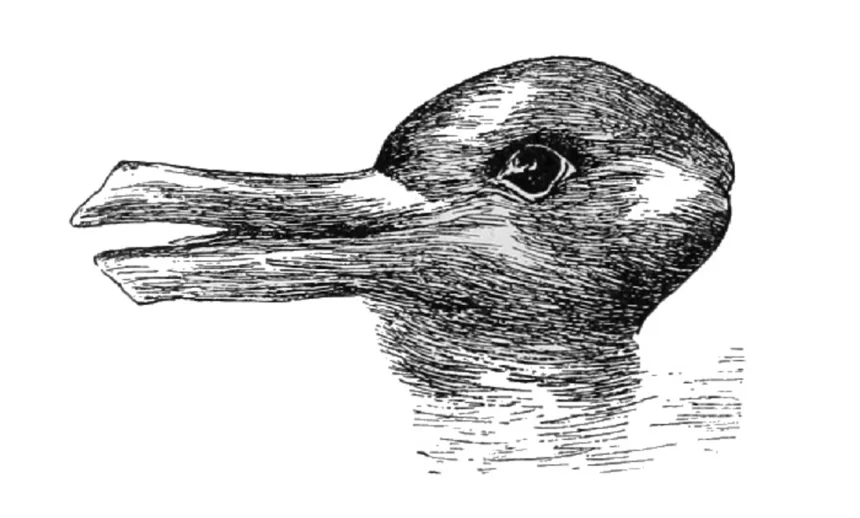

This surrealist satire is a perfect introduction to a tale of duckrabbits, a bunch of postartistic practitioners, stray academics, interdependent curators, pataphysicians, and imaginary activists with whom we mobilized against rising authoritarianism in Poland. In fact, back in 2019, FIELD published my short text Duckrabbits against Fascism. A postartistic postcard from Warsaw in which I reported on this fledgling form of postartistic antiauthoritarianism. There, I introduced duckrabbits—an image that we used to place on our banners—as our spirit animal.

by Kacper Greń (visuals) and Kuba Szreder (text)

As a side note, an image of a duckrabbit, which appears as a duck or a rabbit or both at the same time, is a contemporary of UBU the King. First published in 1892 in the German satirical magazine Fliegende Blätter, it was later picked up by post-philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein. We adopted the duckrabbit as a mascot of postartistic practices, to talk about things we do and actions we concoct—such as demonstrations of paintings, postartistic blocs at antifascist parades, Malevich-inspired pro-Ukrainian performances, or historical performances reconstructed as antiauthoritarian protests. Just as duckrabbits can be viewed as ducks, rabbits, visual jokes, or philosophically charged images, postartistic practices can be framed as art, not art, both, or neither. They are aesthetically charged, politically sharp, philosophically potent, and just cute.

Writing this piece eight years later, I’m trying to revisit the same topic from a different temporal conjuncture. Not only do we currently live through the times of God Emperor Trump, about which the editors of FIELD can tell us much more than I can. In Poland, we are amid a democratic interregnum, which began in October 2023 with elections surprisingly won by a pro-democratic coalition—a brief period of respite between concurrent waves of authoritarian deluge. A moment in between the storms, the silence of which is deafening. It is telling that I find this democratic upheaval much less real than what happened beforehand or what awaits us in the future. There is almost not a single person with whom I talk who would expect a democratic government to keep power after 2027, when the next elections are scheduled. And what lurks ahead is much grimmer than what unfolded during the first reign of the Law and Justice party, just as an upgraded version of Trump is scarier than its previous iteration. The possible future government in Poland will include—probably—outright antisemites, open fascists, crazed libertarians, Putin sympathizers, and Ukraine-haters. Sounds familiar? Here you have it. “Happened in Poland, that is to say everywhere.”

What is most uncanny in the deluge of what Greg Sholette names the “radical unpresent” is the stark feeling that we’re facing a new normal, and that from this vantage point we look at the democratic order as something not properly real, a passing delusion. That’s possibly the most significant difference between 2018 and 2026.

I remember the late October night when we watched the election results, together with my beloved partner, Natalia Romik, and dear friend Helena Chmielewska Szlajfer. We could hardly believe it when we saw the results. We wondered whether this was a moment to pop the champagne or rather not—not yet, not now—remembering all those other nights when we went to sleep hoping for good outcomes, only to wake up the next day facing yet another debacle. This time, though, the pendulum swung in the democratic direction. And yet it felt so unreal, as if it were somehow a glitch—something that we had hoped for over many years, and yet when it happened, it felt somehow misplaced.

It would be easy, and yet potentially misleading, to assess that this bewilderment stems from exposure to supposed forms of new hegemony, when something that was previously unthinkable becomes a new common sense. Especially since this new normal sharply contrasts with the dreams and expectations of my generation, raised in the times when the Iron Curtain fell, the liberal “end of history” was proclaimed, alter-globalism was on the rise, and Occupy movements shaped expectations of radical democracy and democratic socialism. However, it is far too intellectually convenient to mistake one’s own failed hopes for historical analysis. Possibly it is much better to—following Nora Sternfeld’s take on Antonio Gramsci’s less-known passages—not get overly excited or anxious, and to stay calm, as the times in question require sober minds, steady hands, and a sense of historical irony.

Taking a look at the Polish situation, it is hard to miss that authoritarians run on extremely slim electoral majorities. Sometimes the pendulum swings their way, sometimes the other. Once they get into power, they are usually rather incompetent at anything but keeping themselves in government. They live in a la-la land, a toxic mix of historical myths, retrograde utopias, and anxious projections, peppered with a hefty dose of conspiracies. It is good food for Grok’s hallucinations, but not really a blueprint for sound policies. Hence, their prime objective seems to be to distort reality and impair the electoral process, so that they cannot be evicted from power by democratic means.

Nevertheless, whether it is or isn’t a new hegemony, we live in times of global reaction and systemic breakdown, when the liberal global order fades, crumbling under the weight of its own unresolved contradictions and the immense immiseration that it caused. As the old saying goes—every rise of fascism bears witness to failed revolutions. Hence, neoliberal globalization is not replaced by any progressive alternatives but by a swath of authoritarian regimes. It is a nationalist satire of a multipolar world, where the—this time truly former—West is in decline, and anti-Western forces are spearheaded by characters as sinister as Putin, who decolonizes the world by bombing Ukrainian civilians, applauded by Western tankies. Possibly, the surrealist satire of UBU the King is a much more apt metaphor for thinking about the end of our Belle Époque than the much more popular references to the 1920s and 1930s, as it helps us to grasp the shritstorm that—instead of passing—will hover over us for the time being.

Anyway, I was supposed to report on the state-of-the-art world in Poland in 2026. The preceding paragraphs were intended to set the frame, falling prey to my typical feat of intellectual pessimism. Happy to report that it is all good on the Polish front. If not for the larger picture, everything seems to be in perfect order. Soon after the elections in 2023, the major artistic institutions, such as the CCA Ujazdowski Castle or the National Gallery of Art Zachęta in Warsaw, were quickly reclaimed, with directors appointed by the authoritarian government replaced by new faces, mostly selected as a result of open and transparent vetting procedures (which was one of the long-term postulates of artistic trade unions). The Ministry of Culture was—for almost a year—held by Hanna Wróblewska, who by 2022 had been the director of Zachęta before being removed by the Law and Justice government. She proved to be one of the most sensible ministers of culture we have ever had in Poland. She spearheaded a bill providing social security for artists and presided over agreements regulating exhibition fees. The latter was advocated by the artists’ trade union—Citizens’ Forum for Contemporary Art—which solidified itself as the leading association in the field, with a new democratically elected board and numerous members. The new Museum of Modern Art was opened to a grand fanfare in November 2024, after twenty years under construction, and applauded on an international stage. New galleries emerge, and the art market swells. All that seems like a boom.

And yet I cannot shake the feeling that this all is somehow unreal. It is a make-believe artistic universe, which behaves “as if” a return to the good, old democratic order were possible. As if there were no war at our doorstep (Vera Zalutskaya calls this a state of delulu—a shared delusion that the war in Ukraine is not happening). As if fascism were not at our gates. As if the neoliberal global circulation of art did not run on fumes.

To picture this as-if art world, one could hark back to an old joke, which we quoted together with Ewa Majewska in our piece on the early stages of Polish authoritarianism (2016): “In the 1995 movie La Haine, Mathieu Kassovitz’s stinging vision of the plight of the Parisian suburbs, one of the characters tells a joke: ‘Heard about the guy who fell off a skyscraper? On his way down past each floor, he kept saying to reassure himself: so far, so good … so far, so good …so far, so good. How you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land.’” And indeed, in Poland it proved to be a rather hard landing, but somehow our hero miraculously survived, stood up, and now is busy climbing up to the top of the same skyscraper from which he was pushed or jumped only minutes ago. As if one fall was not enough. The neoliberal art world—a Sisyphus of fading globalization. Thinking about it, other images shuffle in front of my inner eye. Such as Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff—the moment when he keeps sprinting after the ground is already gone, suspended in mid-air, before looking down and falling. This visual anecdote was often referenced by many Marxist thinkers to denote ideological systems that run off their material base, clearly the case with neoliberal globalization and the artistic circulation entrenched in it. Or maybe, if I were a bit less forgiving, of a rabbit staring at a snake, or a hare caught paralyzed in the lights of an approaching car, or a suspended train wreck.

You see, that is what becomes of people overtly exposed to the pessimism of intellect. They fall prey to their own anxious projections. Even if we should remain sober in our assessments, and restrained in our judgement, it is somewhat satisfying to rant against the neoliberal lame ducks of the globalized artistic establishment and the legacy institutions in which they have cushioned themselves. The art world establishment is actually just a representative of a wider tendency, of the liberal metropolitan professional class from which it originates, to the tastes of which it caters and from which it mostly fails to distance itself, with a few remarkable exceptions. Importantly, I am not talking here about the rank and file of precarious projectarians, art workers, and other duckrabbits, whose labors are much more in tune with the demands of our times.

I am much less forgiving about the people who manage institutions, rather uninterested in what happens fifty kilometers beyond the doors of their grand new buildings, and yet very keen to get galvanized by Instagram posts from elsewhere. In this attitude, they mimic the worst intellectual habits of their own liberal class of origin. It would not be worthy of attention were it not for the fact that this political vacuum—between the self-indulgent metropolis and its deprived hinterlands—is filled by authoritarians of all kinds. They know how to stir waves of anti-metropolitan sentiment, galvanize them by weaponizing antisemitic, misogynistic, xenophobic, racist, and transphobic clichés, and ride into the halls of power. It seems that liberal politicians are eager to mimic the discursive strategies of the far right, instead of creating and propagating a story of their own, quick to shed a thin veneer of progressivism as soon as the shrit hits the fan.

Just to tell the story from the last presidential elections in Poland in 2025, which were abysmally lost in June by the liberal candidate Rafał Trzaskowski. Contemporary art played only a marginal role in this drama, and yet it serves as a cautionary tale. The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw opened its premises in November 2024, a couple of months before it was fully prepared to show its collection, because the mayor of Warsaw—who was also the liberal presidential candidate—earnestly believed that opening a new grand museum would serve as a good way to launch his campaign. Imagine their surprise when, instead of applause, the museum was ridiculed and not particularly well liked, especially by people who were not its primary audience (saying this, we need to remember that at the same time it was lauded as an enormous success—especially among devotees of contemporary art—and was also objectively visited by ca. 800,000 people in its first year of functioning).

Anyway, this discrepancy between self-indulgent fanfare and popular sentiment was a low-hanging fruit for right-wing culture warriors, who labelled this unliked building “Trzaskowski’s museum” and began attacking it as a leftist metropolitan lodge, a den of queer activists and deranged feminists. In response, the liberal candidate, instead of doubling down on his own convictions, backed down, disavowed the museum, and his aides exerted pressure—unofficially and behind the scenes—on the museum staff not to do “anything controversial” during the electoral period. In other words: to self-censor. Of course, by controversy they meant anything resembling antifascist, feminist, queer, leftist, or progressive programming, and not decisions such as entering sponsorship agreements with large car producers (Audi became the official partner of the museum), using temping agencies to hire art workers (the museum was protested by trade unions because of this), or propping up the fledgling art market (one of the artworks presented in the first exhibition of the museum was eagerly sold at auction just a couple of months after the exhibition ended).

This is anything but surprising. The museum was conceived and constructed as a flagship of neoliberal globalization. Currently, it is still running on the fumes of global artistic circulation, and yet it is utterly dependent on the metropolitan privilege it was built to reinforce. It is a historical irony that, by the very fact of its metropolitan affiliation, it contributes to forces of resentment in its closest vicinity that threaten the political conjuncture on which its survival depends. Not able—and not really interested—in challenging forces beyond their own reach, the institutions in question indulge instead in good old neoliberal progressivism. They pay lip service to democratic ideals while ordering their own shop in accordance with neoliberal managerialism, happily becoming an art-washing laundromat. By centralizing the flow of resources and dominating channels of communication, they impoverish their own hinterlands, stirring up and feeding anti-metropolitan sentiments among communities that pay back in force by helping to elect alt-right politicians who may dismantle the conceptual and institutional edifices of the (neo)liberal art world as soon as they taste power.

In the meantime, duckrabbits hunkered down, took some rest, dispersed, and carried on with whatever duckrabbits do best. In October 2023, it was clear how utterly exhausted everyone was. So do not read me wrong—the democratic victory was a lifesaver, something to be cherished and appreciated. We really were running on our last batteries; after years of constant mobilization, activist burnout kicked in. Especially since the most recent wave of mass mobilization was extremely intense, with a huge collective effort poured into solidarity campaigns with Ukraine, which started immediately after the full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022. It should not be surprising that some friends, after two years of day-by-day activism, took a chance to step back.

Over the last years, some of our colleagues engaged in organizing a string of ecologically minded projects in Opolno Zdrój, a small village on the verge of the largest open-pit mine in Poland, using postartistic sensibilities to tickle the underbelly of extractive economy. Others curated postartistic exhibitions, biennales, or congresses. Some engaged in enacting commons-based programming in artistic institutions, where mixed results were always underpinned by genuine dedication. Some unionized. Some went on strike. Some moved on. Some fought against perennial antisemitism, doing legwork in former shtetles. Some mobilized and organized demonstrations in solidarity with Palestine. Sometimes it was rather tense, with comradeship being tested and resolve challenged, but hopefully those discussions did not devolve into unbridgeable rifts. Duckrabbits, while enjoying a brief period of silence in between the storms, replenished their energies, so very much needed going forward. It is telling that only some searched for greener pastures; most stayed where they were. In Poland, that is to say everywhere.

Well, what can be done? Another joke comes to mind, this one owed to Eva Branscome. A Westerner meets an Eastern European. The first says: the situation is serious, but at least it is not hopeless. The second responds: the situation is hopeless, but at least it is not serious.

And here I hope—laughing against the grimness of our times—that duckrabbits may help us navigate this new normal, where familiar words are twisted and ideas seemingly lose ground. Where fascists advocate against censorship, and leftist activists cancel each other while calling for freedom of expression—only when it is themselves, and not former comrades, who are being cancelled. Let’s not cancel you, not cancel me, let’s cancel this comrade behind the tree. But before I get carried away in my rants against leftist factionalism, let me get back to the matter at hand. When dinosaurs fall, new species evolve. It may be that the artistic institutions of the neoliberal era will not survive the authoritarian deluge. But duckrabbits may. They are small, they are nimble, they are fluffy and cute. What they lack in fangs, they make up for in edgy humor and post-artistic flair. And they excel at navigating a world of enmeshed ambivalence; hence, they may be well equipped to face alt-right doublespeak—a retro-vanguard which Greg Sholette analyzes in his recent writings, pointing out how the alt-right mobilizes insurrectionary imagery in the service of authoritarian delusions. In the end, yet again, it may be about duckrabbits against fascism.

Kuba Szreder is a curator and associate professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Graduate of sociology at the Jagiellonian University (Krakow), he received a PhD from the Loughborough University School of the Arts in 2016. He combines his research with independent curatorial practice. In his interdisciplinary projects he carries out artistic and organizational experiments, hybridizing art with other domains of life. His curatorial work on site-specific projects includes Making Use: Life in Postartistic Times (Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw 2016), Dark Matter Super-collider (S.a.L.E. Docs Venice 2017), Art of Cooperativism (Warsaw Biennale, 2019), Redrawing the Economy (Company Drinks, London 2019), Economics! The Blockbuster (The Whitworth, Manchester 2023), and Hideouts: The Architecture of Survival (Zachęta, Warsaw 2022; Trafo, Szczecin 2022; Jewish Museum, Frankfurt 2024). He initiated and co-curated many research-based platforms and collectives, including Free/ Slow University of Warsaw (2009 – 2016), Centre for Plausible Economies (London 2018-ongoing), Office for Postartistic Services (Warsaw 2020-ongoing). His most recent book, “ABC of the Projectariat. Living and working in a precarious art world,” was published by the Manchester University Press and the Whitworth Museum (2021).