Tools for Dismantling the Oligarchy—Student Protests in Serbia and Their Creativity

Vladan Jeremić and Rena Raedle

The collapse of the recently renovated Novi Sad Railway Station building on November 1, 2024, killed 16 people in the middle of the day, triggered an avalanche of protests in Serbia. This tragedy sparked nationwide outrage, galvanizing citizens and students to demand accountability from a government entrenched in neo-colonial alliances and oligarchic interests.[1] The student movement rose up against the corrupt regime, which has refused to conduct a proper investigation into the cause of the collapse. Students from Serbia’s public universities organized themselves into “plenums” —leaderless, direct-democratic assemblies — and used their institutional autonomy to remain permanently in university buildings, evading the regime’s hostility.[2] The protests have since grown to become the longest and largest in the history of the country.[3]

But long before the tragedy in Novi Sad, environmental and labor protests were constant in Serbia.[4] For years, citizens have mobilized against the regime’s controversial deals with international corporations, most notably the Rio Tinto lithium mining project in western Serbia. The renewal of the agreement, which gives Rio Tinto sweeping rights to exploit the country’s mineral wealth with minimal environmental safeguards, sparked protests against neo-colonial exploitation and land grabbing.[5] Parallel to these struggles, education and cultural workers have led sustained protests since the pandemic, denouncing stagnant wages and a crumbling public education infrastructure. Additional challenges related to Serbia’s accession to the European Union have created more confusion and the emergence of neo-colonial relations,[6] with various international forces influencing Serbia’s own agendas.[7]

Despite demanding responsibility for the tragedy, state violence against the students have increased and the methods and tactics of peaceful struggle used by the student movement have become very diverse. The movement has redefined protest itself, combining direct democracy with protest creativity, organizing workshops for making flags, banners and protest accessories, exhibitions, street performances and other motivational forms, such as running a hundred miles from city to city to wake up citizens from smaller towns and villages, or organizing a bicycle tour from Belgrade to Strasbourg via Budapest, Vienna and Munich. What is happening here shows a real enthusiasm; a growing optimism with a “conscious naivety” that has become unstoppable. For five months now, the protest creativity of the student movement has been taking place on the streets and in digital spaces. Memes, murals, and performances satirize the absurdities and violence of the regime. Crucially, student protest art avoids didacticism; it invites the participation of citizens and ordinary people. By erasing individual authorship, it reflects the egalitarian ethos of the movement, in which every protester is a co-creator.

Unlike the leader-driven movements of the 1990s, today’s “plenums” operate horizontally, recalling Yugoslavia’s workers’ councils and socialist self-management. Even the exhibitions by students from the University of Arts in Belgrade in Kula Gallery[8] presented collaborative protest artworks without crediting individuals, instead emphasizing historical continuity, linking 2024-25 to the revolutionary spirit of 1968 and the anti-war rallies of the 1990s. Student protest art consciously dialogues with the region’s complex past. The 1968 student protests in socialist Yugoslavia criticized the bureaucratic class while demanding more socialism and greater freedoms, blending Marxist theory with liberalism. The 1996-97 anti-Milošević protests, by contrast, aligned themselves with liberal values, their aesthetics borrowing from the iconography of globalized “democracy”. Today’s movement rejects both frameworks, seeking a “third way” rooted in the Balkan traditions of non-alignment and solidarity.

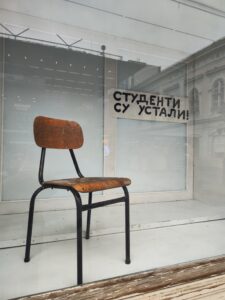

The students’ artistic productions transcend the boundaries of what might be expected to be activist art in the context of large-scale protests. These artistic expressions are not merely instruments of persuasion; rather, they function as conduits for engagement. The medium of art thus became democratic, characterized by its accessibility, practicality, and inseparability from the demands of the protests. At the Faculty of Fine Arts, art students placed an empty chair with the slogan “The Students Have Risen Up” in a window overlooking Belgrade’s main pedestrian street. This conceptual piece – at once haunting and defiant – criticized the regime’s lack of accountability while asserting the movement’s presence. Similarly, a collaboratively built large sculpture of the Trojan Horse, which was taken to the Supreme Court, became a mobile symbol of systemic deception before being displayed at the ULUS Gallery, where visitors exchanged donations for T-shirts, badges, posters, and other student-made protest materials.

A more than symbolic victory came with the liberation of Belgrade’s Students’ Cultural Center (SKC),[9] a historic center of Yugoslav conceptual art in the 1970s, where pioneers such as Marina Abramović, Raša Todosijević and, Goran Djordjević staged radical performances and exhibitions during the socialist era.[10] By reclaiming this neglected space, the students revived its legacy and transformed it into an autonomous space for workshops, concerts, exhibitions, and protest planning. The SKC became both a shelter and a stage, merging artistic practice with further mobilization. Re-born as a protest nexus, the SKC echoes its 1970s radicalism, but with a 21st-century twist: here, art is not just for critique, but also for “building” — a tool to dismantle oligarchy and prefigure a world where creativity and direct democracy are one. By erasing the line between creator and participant, the students have proposed a model in which life, struggle, and creativity are inseparable. Their proposal rejects neoliberal individualism and imported “solutions” in favor of reviving regional traditions of collective resistance. While the regime persists, the movement has already reshaped Serbia’s cultural landscape. In a world sliding toward authoritarianism, Serbia’s students offer a defiant lesson: the future of resistance lies not only in the streets, but in the collective reimagining of what a better society could be.

Vladan Jeremić is a Yugoslavian-born artist and cultural theorist with a Ph.D. from the University of Belgrade. In his collaborative practice with his partner Rena Raedle as artists, curators and writers, they explore the relationship between art and politics, exposing the contradictions of contemporary societies and exploring the transformative potential of art. For more than two decades, they have been actively involved in struggles around culture, social rights, and housing. They develop the transformative potential of art in the context of social struggles and in collaboration with social movements. They have edited numerous publications on migration and socially engaged artistic practice. Vladan Jeremić is co-founder and editor of the ArtLeaks publication ArtLeaks Gazette, which deals with the abuse of the professional integrity of cultural workers and the open violation of their labor rights.

Notes

- Dusanka Milosavljevic, https://www.birgun.net/haber/a-new-generation-politicized-by-struggle-612556 ↑

- Vida Knežević and Marijana Cvetković, https://internationaleonline.org/contributions/mass-student-protests-in-serbia-the-possibility-of-different-social-relations/ ↑

- Jennifer Rankin, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/mar/15/tensions-mount-in-serbia-as-protesters-converge-on-belgrade ↑

- Iskra Krstić, András Juhász, https://www.rosalux.de/en/news/id/53246/serbias-student-movement-is-rekindling-hope ↑

- FT, https://www.ft.com/content/a916bcb8-a779-412f-8772-ea0f88f10bd9 ↑

- Today’s Serbia has been reduced to a status similar to that of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia before World War II, because it has become a mining colony of global corporations, just as it was during the Kingdom. ↑

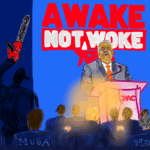

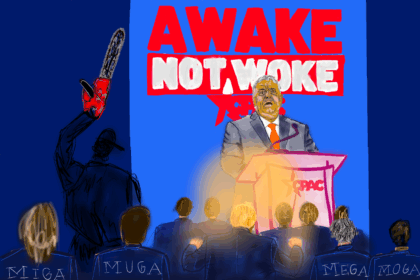

- Serbian President Vučić’s invitation to Donald Trump Jr. to build a Trump Tower on the site of Belgrade’s army headquarters, which was bombed by NATO in 1999, shows a toxic alliance. Serbian citizens have responded with sharp satire, using memes that juxtapos Trump Jr. and Vučić with images of protests in Belgrade that have circulated on social media. Architects, citizens, and artists have come together and organized several exhibitions and protest events to protect the building and oppose the Trump Tower deal.https://www.reuters.com/world/donald-trump-jr-visits-serbia-meets-president-aleksandar-vucic-2025-03-11/and https://www.europanostra.org/europa-nostra-statement-protecting-belgrade-generalstab-is-a-matter-of-law-and-public-interest/ ↑

- Vreme, https://vreme.com/en/kultura/stuudenti-sada-je-to-nas-zivot/ ↑

- Vreme, https://vreme.com/en/vesti/studenti-blokirali-skc-ulazak-samo-sa-indeksom/ ↑

- It is interesting to note that Marina Abramović recently made a video performance dedicated to the victims of the Novi Sad tragedy and the student movement in Serbia and shared it on her social media. Her purely symbolic gesture attracted no significant attention. https://www.instagram.com/abramovicinstitute/ ↑