Becoming Engaged: A Subjective Cartography of Art and Policy in Italy

Emanuele Rinaldo Meschini

The historical reconstruction I propose below is based on the study and analysis of various sources and testimonies, continuously referring to both state policies and cultural spheres. It is a reconstruction of the system, meaning the events and actions (in a broad sense, not only prescriptive), that led to the formation and formalization of an integrated system of art-based policies—or rather, policies that emerged from an artistic foundation. More specifically, it traces how exogenous and external forces—particularly certain state and municipal policies—contributed to the development of a state cultural system in Italy that incorporated urban regeneration within its media and recognition frameworks. This research spans approximately 25 years and fundamentally examines the relationship between artistic practices and policies, focusing first on the role of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport and later the Ministry of Culture. It does not include a detailed analysis of grassroots practices, which, while constituting an important part of this narrative, require a separate examination of parallel moments and data.[1] This study has been developed both through direct participation and practice, as well as through academic research, over a period from 1998 to 2022.

Framework and Acknowledgements

The linearity of the reconstruction presented here should be understood primarily as an ex-post narrative. Historical causality often appears coherent only in retrospect, obscuring the contingencies, coincidences, and intentions that shaped events as they unfolded. As Raymond Aron reminds us in Introduction à la philosophie de l’histoire (1961), historians are prone to what he calls the “retrospective illusion of inevitability”—the tendency to reconstruct the past as a deterministic sequence, overlooking alternative paths and interpretations. For Aron, contingency means not only the possibility that things could have turned out differently, but also the impossibility of fully deducing events from prior conditions. This methodological reflection stems from my multifaceted involvement in this history—initially as a curator, then as a doctoral researcher, artist, and, more recently, academic scholar. My background in art history informs a subjective position that can be seen as enhancing rather than compromising objectivity. Drawing on Enzo Traverso’s notion[2] of multiple “selves,” I recognize the coexistence of different layers of identity within this trajectory: the curator engaging with community-based art projects; the doctoral researcher (2016–2020) exploring the gap between internationally recognized socially engaged art and its Italian counterparts; the artist navigating urban regeneration programs through direct involvement; and the current researcher in the sociology of culture, striving to bridge theory and practice while formalizing these experiences within academic settings. Rather than masking these identities behind a unified methodological lens, I view their interplay as essential to understanding the vitality of the research process. These “selves”—positional, investigative, and emotional—contribute to a deeper engagement with the field. In line with the scope of this journal, the following text offers a condensed account of an evolving research project: once that has clarified certain historical phases (particularly the 1990s and early 2000s), yet remains open to the influence of ongoing social transformations and policy developments. The situated context of this research is Italy.

Text and Context

For approximately twenty years, in the international artworld, the term social turn has been systematically and formally discussed from a semantic perspective. This does not imply that socially or politically engaged artistic practices originated in the early 2000s; rather, it indicates that a different kind of politics and social engagement were redefined during that period—along with the work and role of the artist. Like any turn, this shift represented a moment of change, granting visibility and a name to practices in search of definition that operated in “grey areas”. However, as demonstrated by various articles in this journal—as well as by its overall framework—there is a fundamental distinction between the specific socio-political context of a particular area and the transnational, cross-cutting realm of the contemporary art system. The latter, often in the name of a presumed Enlightenment aesthetic principle, tends to replicate itself, maintaining its own symbolic purity as noted by Grant Kester in his latest book.[3] Within this classic dissociation between mind and body, practice and theory, the aim of this text is to examine the transformation of artistic practice through its encounters, conflicts, and negotiations with policies related both to urban regeneration and to national welfare systems in Italy. These explicitly political and social intentions embedded in artistic practice—as well as in the broader system—have contributed to a redefinition of its characteristics, aligning it with the integrated artistic planning approaches that have been present for years in Northern Europe and the United States. This transformation not only affects artistic practice but is also driving a methodological redefinition of how to analyze such practices beyond disciplinary boundaries.

Public Art in Italy. The Nineties Debate

In Italy, throughout the 1990s, the debate around the function and role of public art developed through a multiplicity of actions and experiences, ranging from spontaneous and autonomous initiatives to more institutionalized ones. It is important to recall, however, that the contemporary art system in its more experimental form began to develop systematically precisely during those years. As such, the dialogue with Ministry of Culture and its specific Directorates—which is the main focus of this text—was largely absent, or at least marginal. At the time, artists and curators—such as Marco Vaglieri, Cesare Pietroiusti, Roberto Pinto, Emanuele De Cecco, Claudia Losi, and Eva Marisaldi, to name just a few—were not embedded within a ministerial framework of urban policy as we now know it. Therefore, the discourse around artistic practices in the urban sphere was articulated through a plurality of perspectives and fields of action. In this context, I propose to revisit a paradigmatic moment of that period: a debate held on October 3, 1999, during the Venice Biennale curated by Harald Szeemann. This allows us to frame both autonomous (through the presence of specific artists) and institutional (through the broader regulatory dimensions of the field) system.

From a contextual perspective, Italian engaged artistic practice at the turn of the late 1990s and early 2000s, was in a fragmented and still “pioneering” phase, where the literal translation of “socially” (socialmente) seemed more closely linked to the political practices of the 1970s, often associated with visual arts.[4] Between the late 1990s and early 2000s, amidst both spontaneous artistic actions in urban space and those embedded in specific urban contexts, Italian art criticism began to reflect on the various experiences and iterations of public art (arte pubblica).[5] This reflection was shaped by social and cultural changes occurring in other countries, where theoretical discussions had led to significant conceptual and terminological shifts, such as those associated with community art and new genre public art.[6] The desire to reason in terms of arte pubblica—a term often used in Italy in its English form public art—emerged precisely from these contextual differences. Thus, in 1999 at the Venice Biennale, the critic and curator Alessandra Pioselli, during a seminar held within the spaces dedicated to the Oreste Project (Progetto Oreste)—an informal group composed of various artists participating in that edition of the Biennale, who, while working together, deliberately avoided adopting the formal structure and logic of an artist collective—sought to assemble what were then considered the key critical and practical experiences in the field to update the discourse around public art.[7] Within this socio-political context, the primary challenge for public art was to move beyond its predominantly historical dimension, where sculptural monuments and the use of public space as an extension of the gallery or museum, played a dominant role. This departure, and the transcendence of public art’s historical dimension, was also understood as a way to overcome an ideological history, as Pioselli pointed out, stressing the ontological difference between past and present in terms of political engagement. During the 1990s, a new—yet familiar—operative term began to emerge in the discourse around public art: participation. The notion of participation was so dense and historically charged that Pioselli felt the need to clarify and reframe its meaning in light of its complex legacy:

On this subject it is interesting to quote the reflection about the Seventies, underlining the concept of “participating”, a key word for artist practices in urban territory during that period. Those “actions” were marked by a protesting and oppositional component. The work was addressed to a collective corp (citizens, workers, women, students, etc..), regarded as constituting a political identity. […] Nowadays even if some ways of working are similar, the idea of the receiver is different: it’s not a “political corps”, but people with real life experience. The relation is not between cultural operator and the public, but it is direct. Moreover, the interventions are subtle: they act as a virus, without declaring an opposition to the social system, but stressing its contradictions.[8]

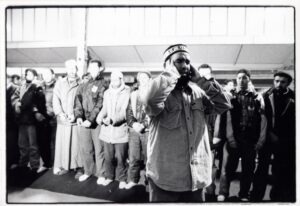

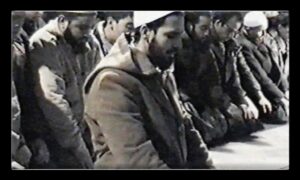

How, then, does artistic practice—specifically public art—position itself within a new, global social context, increasingly distanced from its former directives of history and politics? Through her presentation of Italian case studies (Adriana Torregrossa, Paola Di Bello, Wurkmos) and international examples (Projects Environment, WochenKlausur), Pioselli illustrated the alternative and differing approaches “available” to artistic practices operating in urban and public spaces at the threshold of a new non-political and non-historical context—one that neoliberal capitalism would begin to shape at the turn of the 2000s. Operating outside the well known routes of museums and biennials, artistic practice, in order to avoid isolation, had to engage with cultural policies. The question posed at the time was precisely how to do so. One of the primary examples discussed—because it was the first of its kind—was Art.2, an intervention carried out by the artist Adriana Torregrossa in Turin (1999) as part of the European urban regeneration project The Gate. The intervention conceived by the artist took place inside the covered market of Porta Palazzo—one of the largest indoor markets in Europe—which, at the time, like the rest of the city of Turin, was undergoing significant transformation due to the settlement of new communities, particularly a community of more recent Muslim immigrants mostly coming from Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco.

The artist therefore decided to bring visibility to these emerging subjectivities within the Italian context by organizing a mimetic event: a public celebration—inside the market—of the prayer marking the end of Ramadan. The intervention can be understood as mimetic in nature, in that it replicated an everyday gesture and operated without clearly defined boundaries: there was no designated “stage” for the artistic action, no explanatory labels contextualizing what was taking place, and—perhaps most significantly—the participants themselves were not artists.

For the first time during those years, Muslim religion and its practices—often heavily stereotyped and ostracized by segments of the political sphere and public opinion—were made visible within a public and commercial space such as a marketplace, provoking an immediate reaction, particularly from members of the then Lega Nord party (the “Northern League,” a far-right political formation now almost defunct, but from which former Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini originated), who responded by promoting a counter mass in Latin aimed at “purifying” the space. This was the first instance in which the relationship between artistic practice and urban regeneration, understood as an urban policy, was discussed. The concept of regeneration —”absent from the lexicon of public art in the Italian context” (Pioselli)—was seen as strongly resonant with a specific artistic practice, as it emphasizes the intent to operate based on the existing, on the specificity of lived experiences intertwined within a given territory. The resonance between certain artistic practices and these new frameworks of urban regeneration stemmed from a shared commitment to social openness—an approach that aligned with artistic practice attentive to the inclusion of new languages and willing to recognize—not through bureaucratic mediation or institutional political discourse, but in a more direct way—people over “cultural objects”. From this perspective, Adriana Torregrossa’s intervention within the market space was by no means incidental; rather, it aligned closely with the social contours of the broader project. The Gate specifically included actions addressing urban regeneration with a focus on the inclusion of migrant communities and their integration into a more formalized and stabilized local economy—particularly from a social standpoint. In this regard, I would like to highlight three targeted initiatives promoted by The Gate that addressed the needs of both the local population and immigrant residents: the opening of a job-matching service aimed at facilitating access to the labor market for both Italian and non-EU citizens; a neighborhood information desk providing guidance on housing issues, including how to avoid exploitation and promote shared rules of civil coexistence; and a support center for sex workers, with particular attention to the situation of foreign women. These actions were complemented by consulting services for immigrants wishing to open a business in the neighborhood, as well as proposals for establishing a small ethnic market within Porta Palazzo, managed by a migrant association—an attempt to “regularize the unresolvable,” that is, to find flexible and pragmatic solutions to counter the informal economy.

Rather than imposing a top-down mechanism where “quality” is preconceived and superimposed onto the socio-cultural fabric, this approach begins from existing conditions, in this case Turin, revealing their potential and richness. This approach aligns with a practice—whether artistic or social—that takes place in situ within a given territory and unfolds through listening, accompaniment, and patience. Within this integrated perspective—where urban policies (since The Gate was part of a complex urban project) and artistic practice intersect—the role of the artist is also redefined. In these processes, according to Pioselli, the artist becomes an “inventor of services” and urgencies, though not in a purely instrumental sense. In contrast to this position—which could be considered systemic in its embeddedness within a structure, though not necessarily systematized in a codified manner—Pioselli presented the example of the British collective Projects Environment. Given the UK government’s greater familiarity with integrated approaches between art and urban policy, the work made by Projects Environment was used as a warning for the risks of fetishizing political engagement. Pioselli stated: “Projects Environment draws attention to the risks of fetishization by artists regarding social engagement. Warning against the dangers of “simplification”, they oppose the application of an operational formula in favor of a constant re-evaluation of intervention methods. These methods cannot—according to Projects Environment’s political stance—ignore the “complicity” that socially engaged art may develop with institutions.”[9] After outlining this international interaction, Pioselli acknowledged not only the contextual limitations—specifically in terms of policies—but also the absence of a critical debate on these issues in Italy:

“As curators of this discussion, we must acknowledge the vastness of the subject we aimed to address [art, urban space, and regeneration]. To this summary of the initiative’s key features, we intend to follow up with a more extensive theoretical reflection. The evident absence of theoretical contributions on this subject in Italy (whereas in other countries it is the focus of programs, competitions, university courses, etc.) encourages us to continue collecting experiences while also engaging in theoretical work—something we see as absolutely necessary, both from a critical and curatorial perspective.”[10]

Thus, in 1999, Italian art criticism was beginning to outline possible directions for a new form of public art—situated in the tensions between the “invention of service” within integrated urban policy systems, such as complex urban regeneration programs, and, at the same time, the risk of fetishizing political engagement and co-opting artistic intervention. Above all, as mentioned, the absence of a critical debate on the subject was becoming evident. In that moment of theoretical and practical repositioning, the adoption of the English term public art proved effective, as it allowed for a detachment from the historically and ideologically charged Italian notion of arte pubblica, particularly in relation to public funding and the bureaucratic and ideological frameworks of the 1940s, post-war period,[11] as well as the political movements of the Seventies. In recent years, I have written critically about the literal transposition of the term public art, often in rather sharp and negative terms, highlighting what I perceived as the “inability” of Italian art criticism and the evolving art system to move beyond an emulative framework—one that sought similarities and validations in pre-existing established practices from other countries rather than recognizing their innovative potential (in Italy).[12] It seemed to me—and this was my primary critique—that despite the emergence of new experiences brought about by art practices genuinely connected, such as the project made by Torregrossa, to social dynamics and, in some cases, decision-making processes in policy, the choice remained to adhere to an authorial and art-centered form such as public art, even defined in English.

For me, as a doctoral researcher, this signified the absence of a collective will—a body composed of art, politics, and the social realm—that would choose the dimension of construction over, as I mentioned earlier, that of resemblance. My re-thinking of the concept of the “political body,”[13] and in some respects its very impossibility, was shaped through an ongoing exchange with colleagues, scholars, artists, and professors, both within and beyond academic spaces, with whom I have engaged in sustained conversations on the subject. This was largely because I continued to think in a mode that was essentially aesthetic—removed from politics and shaped by a certain idealist tradition that tended to embrace the indeterminacy of art’s social role and conceptual function. During my doctoral years, I had the opportunity to take part in a master seminar on public debate and participatory local action (led by Professor Francesca Gelli, University Iuav, Venice), where I was introduced to grassroots initiatives engaged in co-designed artistic and social practices within urban neighborhoods often labeled as “difficult,” such as Tor Bella Monaca in Rome and San Siro in Milan. This also prompted me to revise some of my previous statements in favor of a broader contextual understanding—an awareness that disciplinary blinders had likely previously prevented me from fully grasping. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Northern European countries—alongside the United States where the artistic consciousness of the social turn was maturing—were undergoing a neoliberal political shift and, more broadly, a socio-cultural transformation (almost a redefinition) that Italy had not yet embarked upon. Thus, the decision to label socially engaged-style operations as public art did not necessarily stem from a critical shortcoming within the art system but rather from a specific contextual absence at political level. While there was arguably a lack of art critique, the operational context itself made any application of the vocabulary of socially engaged art practices in Italy particularly challenging.

Waiting for Godot: For Better or Worse

It may seem paradoxical—perhaps even reductive—but socially engaged art cannot exist outside of a neoliberal political system. The erosion of shared life and participatory structures brought about by this economic and political model has made it necessary to imagine—not just symbolically but also practically—alternative and prefigurative forms of governance. During these years, the socially engaged dimension I was waiting for—much like Beckett’s Godot—materialized through its intersection with state policies. Over the past two decades (the approximation is due to the ongoing nature of these processes, which are not yet fully historicized), Italy has progressively adopted policy models increasingly aligned with a neoliberal framework, a trajectory that began later here than in countries such as the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, which are often taken as reference points both in the artistic field and in policymaking. While the U.K. had already embarked on this neoliberal shift with Margaret Thatcher’s reforms in the 1980s—later continued under Tony Blair’s New Labour, which Claire Bishop references to contextualize her notion of the social turn—France and Germany initiated similar transformations in the 1990s. Italy, by contrast didn’t consolidate its neoliberal orientation until after the 2008 financial crisis, through welfare and labor market reforms, such as the Fornero Law (2011) and the Jobs Act (2014).[14]

Alongside these political and policy shifts, a profound social and demographic transformation reshaped the social fabric of many European countries. Notably, while the U.K., France, and Germany had already experienced significant migration flows from the 1960s and 1970s—partly due to their colonial histories—leading to greater ethnic and cultural diversity and a subsequent redefinition of national identity, Italy only began to experience a substantial increase in migration in the 1990s, influencing its social and economic composition more recently. In 1981, the first ISTAT [The Italian National Institute of Statistics] census recorded 321,000 foreign residents in Italy, of whom approximately one-third were classified as “permanent” and the rest as “temporary.”[15] By 1991, the number had doubled to 625,000, marking 1991 as a symbolic turning point, when Italy transitioned definitively from a country of emigration to one of immigration. More than thirty years after the enactment of the current citizenship law (Law 91/1992), the country has undergone a profound demographic transformation: Italy has fully evolved into an immigration country, where migration has become a structural characteristic. As of 2023, children born to two foreign parents amounted to 53,079, representing 13.5% of total births (ISTAT, 2023). Since socially engaged practices “require” a specific political, social, and economic framework to emerge, this contextual fabric becomes a necessary premise for understanding how certain artistic practices have evolved into integrated forms of policy.[16]

Bridging Policy and Artistic Practice

In recent years, the convergence of specific policies with certain artistic practices has given rise to new forms of fusion and experimentation, prompting Italy—through our case studies and direct experience—to question what had already occurred in the early 2000s in other countries, particularly in Northern Europe.[17] When I studied the tension between ethics and aesthetics through case studies such as WochenKlausur, Oda Projesi, Schlingensief, or Santiago Sierra. I struggled to grasp its tangible relevance within the Italian context, where the debate appeared ideologically polarized between positions of autonomy and institutionalization. The latter, in particular, tended to recast socially engaged artistic practices within conventional curatorial frames, primarily focused on their aesthetic dimension, while failing to provide a historical or social analysis of the conditions that had originally produced such interventions. One example in this regard is The Independent, a research-based project dedicated to independent thought and action that the MAXXI (Rome)—National Museum of 21st Century Arts—has been supporting since 2014.[18] Today, in some respects, we have moved beyond this deadlock between the apocalyptic and the integrated to quote Umberto Eco[19] and we have entered a lived process in which terminologies are no longer merely a priori categories, but are continually revised in light of new innovations in practice. This shift has been largely driven by the policies developed in Italy over the past twenty years, which have introduced a third actor—a broad hybrid of civil associations and the third sector—into the realm of social welfare policies and dynamics. Given this broader contextual framework, the aim of the following study is to analyze the trajectory that has led to the integration of artistic practices and urban policy, especially those devoted to process of urban regeneration.

To begin, I would like to offer a definition of urban regeneration within the Italian critical academic context, particularly as it pertains to the fields of planning and urban design. I propose a definition that synthesizes the thinking of Carlo Cellamare and Massimo Bricocoli, two key figures in the Italian discourse on urban regeneration—especially from a critical perspective attentive to social, spatial, and participatory dimensions. For Cellamare and Bricocoli, urban regeneration cannot be reduced to a technical or urbanistic intervention, nor can it be equated with real estate valorization strategies. Rather, it should be understood as a social and political process that encompasses: the material and symbolic transformation of territories; the active involvement of local communities; and the production of meaning, relationships, and conflict within urban space. In their view, regeneration is not a neutral act, but one that carries specific visions and interests: it may generate inclusion or exclusion, empowerment or marginalization, depending on who promotes it, how it is implemented, and with what objectives.[20]

This essay seeks to explore how macro (state funding) and micro-policies (local government) form an interconnected system capable of mutual influence and intersection. The objective is to move beyond a dichotomy between ethics and aesthetics, between self-organized projects and collaboration with state policies which risks flattening the discussion and preventing a more nuanced understanding. As Enrico Crispolti—one of the first critics to seriously engage with the relationship between visual arts and social participation in Italy—argued, the challenge is to step outside the self-referential world of contemporary art. To develop this analysis, I will focus, on the evolution of Italian public art over the past few years, particularly the proposals launched by the Ministry of Culture, which have increasingly involved artistic practices in urban regeneration initiatives, later officially defined as cultural-led urban regeneration projects. One of the pivotal moments marking this intersection between public policy and artistic practice is represented by the Creative Living Lab funding programs.

No Fixed Methodology for Participation. Neighborhood Contracts and Complex Urban Programs (1998–2002)[21]

The process that led to the launch of the first edition of the ministerial competition Creative Living Lab in 2018—organized by the Ministry of Culture, where artistic practice and urban regeneration are placed on an operationally equal footing—which has its roots in a much earlier period and, above all, originates outside the traditional art world. Before reaching a fully developed model of cultural-led urban regeneration, a phase of learning and experimentation took place, specifically in the form of the so-called Neighborhood Contracts (Contratti di Quartiere). Neighborhood Contracts emerged as an experimental approach to sustainable housing, following models developed in Northern Europe—particularly in the Netherlands—since the 1970s. In Italy, the 1990s marked a period of adaptation and modernization of sustainable practices, as well as a response to the rigidity of traditional urban planning. Neighborhood Contracts introduced a new governance model aimed at testing innovative strategies and methodologies that could ensure/encourage the active participation of representative stakeholders and citizens in the planning, design, and management of urban spaces. Neighborhood Contracts are part of broader complex of urban programs that signal a shift in Italy from a primarily expansionist phase—linked to large-scale post-war settlement projects—to a transformative strategy based on urban renewal and the redevelopment and refunctionalization of existing spaces. This transition marked a new approach to urban issues, incorporating a more integrated system of actions, rather than relying solely on a sectoral intervention model (housing, infrastructure, services, etc.)[22].

The integrated nature of these interventions fostered a process of “spontaneous” innovation in architectural and urban planning methodologies. Neighborhood Contracts were implemented in two phases: 1998 and 2002. The first phase had an experimental focus while the second aimed at a more systematic and institutionalized approach. First introduced by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport (formerly the Ministry of Public Works) in 1998, these contracts represented one of the most significant initiatives undertaken by the Ministry in the field of urban regeneration. Their implementation followed the growing recognition of the inadequacy [e.g., the deterioration of housing infrastructure, lack of public services and infrastructures, etc.] of many urban areas. In this context, Neighborhood Contracts are of interest not only as a precursor to the integration of artistic practice with urban planning but also because they introduce those fundamental elements used by socially engaged art, such as participation, dialogue, and co-design—albeit in an initial and still unstructured manner. These contracts function as negotiated and complex mechanisms that establish a dialogue between public and private actors—including citizens—seeking agreements rather than imposing top-down solutions. They represent a negotiation between the specific needs of a place and the broader directives of central governance. The primary goal was the “improvement of services and infrastructure networks in degraded public housing districts,” with a particular focus on peripheral or abandoned areas. In the 1998 phase, a crucial term for socially engaged practice made its first appearance in this field: participation. It is important to emphasize that at this stage, the relationship between artists, policy frameworks, and the urban context was not yet codified. However, this was the moment when both the semantic and practical foundations were laid for future systematic collaborations. The Guidelines for the first Neighborhood Contracts explicitly state: “Participatory urban renewal programs are tools linked to urban planning, architecture, and the design of public spaces (particularly squares and parks), which take into account the needs and ideas of those who will inhabit these spaces. They represent the possibility of implementing shared and participatory development processes. […] There is no fixed methodology to follow in the implementation of participatory urban renewal programs”[23] (Translated by the author).

Although participation was still in the process of being methodologically defined, it became part of a set of practices aimed at redefining the relationship between citizens and the city. The first phase of Neighborhood Contracts was particularly focused on inclusive, participatory processes and the creation of shared experiences in which decision-making was distributed. The emphasis on local governance and the handover of responsibilities activated participatory processes, significantly contributing to the transformation of neglected areas, especially public housing settlements. These initiatives combined urban and architectural interventions with measures to increase employment and reduce social hardship. The first edition of the program involved 57 municipalities, and a set of 46 individual projects. Among these, 26 implemented participatory strategies, including participatory design, community workshops, and the collective management of activities and initiatives.[24] In the directives of the second phase of Contratti di Quartiere II (2002), the first intervention methodologies began to take shape:

“The participation of the local community—residents, associations, and economic operators—is fundamental in defining the objectives to be pursued, implementing actions, and monitoring results to ensure shared interventions. The participatory approach implies the active involvement of potential beneficiaries in the various phases of a plan, starting from its conception, following what is also defined as a bottom-up approach. The primary field of application for participatory systems is urban planning, where different categories of ‘participatory methodologies’ exist (ranging from small group activities such as focus groups or meta-plan sessions to large-scale consultation techniques).” (Translated by the author)

These were the years in which integrated design approaches began to take hold across Italy, redefining both the responsibilities and the very role of the artist. Although, as mentioned earlier, the art practices involved in these programs were still categorized under the broad term public art.

Towards a Structure: It Seems Socially Engaged but it’s “Still” Public Art

At the end of the 1990s, artistic interventions started to become part of complex urban programs, such as The Gate and Urban II—both in the city of Turin. The Gate project in the Porta Palazzo area, mentioned earlier, was an initiative promoted by the European Union aimed at fostering economic revitalization and improving the quality of life and the environment, while the project Urban II was placed in the Mirafiori Nord district. This area was historically linked to the presence of the Fiat Mirafiori automobile plant, which began operations in 1939 and, for years, was Italy’s most significant industrial facility and one of the largest automobile factories in Europe—defining the district through its strong working-class identity. A total of 40 million euros were allocated for Urban II, and the project was formally launched in 2001 after being selected as one of the ten winning proposals in a national competition organized by the then Ministry of Public Works, in response to a European Union call for projects. To develop a sustainable urban program, the primary objective of Urban II was to “Promote the development and implementation of particularly innovative strategies to foster the sustainable economic and social recovery of Mirafiori Nord, while encouraging the exchange of knowledge and experiences on urban revitalization and sustainable development within the European Union.” (Translated by the author). Within this broader urban initiative, a specific artistic intervention was introduced through the Nouveaux Commanditaires (New Patrons) program, curated by the collective a.titolo.[25] The Nouveaux Commanditaires program was established in France in 1991 by the artist François Hers and initially developed with the support of the Fondation de France in Paris. Its goal was to redefine the role and responsibility of all social actors involved in the creation of an artwork in public space, responding to a demand for art that addresses issues of quality of life, social integration, and urban regeneration The Nouveaux Commanditaires, called in Italian Nuovi Committenti, thus marked the formal integration of a new artistic practice within the framework of urban regeneration in Italy. As the art critic Alessandra Pioselli writes:

Artistic planning was effectively integrated into territorial regeneration strategies, falling under the jurisdiction of various municipal departments for urban planning and peripheral development. In Turin, Nuovi Committenti was included among the actions of the Urban II-Mirafiori Nord program, and a.titolo utilized the instruments activated by the initiative, such as the social table. Framed within a procedural structure—rather than being simply layered onto the project’s completion, as is often the case—artistic practice can play a role in bringing to light perspectives that may not be considered priorities by institutions.[26] [translated by author]

Commissions for artistic projects were awarded to several artists, many of whom were recognized figures in the contemporary art system at an international level, including Stefano Arienti, Massimo Bartolini, and Lucy Orta, among others. However, as defined by the curators themselves, the nature of the interventions presented was more aligned with a definition of public art, albeit in a more dialogic sense, rather than socially engaged art, as in many cases, the outcome of the operation materialized as a tangible artistic object (as in Orta’s case), maintaining a largely authorial approach. In my previous analysis of the project, I specifically focused on this terminological “closure,” which carries interpretative elements closer to an art-based sphere rather than a community or socially engaged framework.[27] The projects presented alternated between a community-driven design process and a more authorial perspective. While I still believe that this classification excessively confined the project within a self-referential artistic domain, I now better understand the mitigating factors related to the challenges of working in an “urbanistic” context that was still relatively new and uncertain. This uncertainty inevitably influenced the definition of a practice that, in its initial phase, required a process of testing and refinement. Therefore, rather than focusing on authorial emulation or the mere production of an artistic product, it is essential to highlight the efforts of artists who, despite being part of, and recognized by, an art-based system, attempted to mediate their approach in the context of the urban public sphere. They brought a language, typically elitist and refined, into contexts situated outside conventional “cultural circuits.”

One of the critiques often directed at projects of this nature—similar to Miwon Kwon’s critique of Culture in Action—concerns their underlying paternalistic artistic approach, an aspect that, to some extent, also influenced the Nouveaux Commanditaires program. This critique stems from the assumption that art inherently possesses an “emancipatory” function, reinforcing the deep aesthetic divide between the artist—conceived as a conscious and knowledgeable producer—and the audience—seen as a passive recipient in need of guidance. If this divide is not acknowledged and critically addressed, there is a risk that artistic projects will ultimately serve to simply validate specific government policies, a concern raised in the analyses of both Pioselli and Bishop but with different overtones. However, this issue is not exclusive to the Turin project but rather reflects a broader instrumental and utilitarian mindset that, whether consciously or not, still pervades many socially engaged projects today. Of course, such a “distortion” can only occur under specific political and social conditions—where themes such as representation, participation, and co-design do not stem from a genuine grassroots need, nor are supported by targeted policies. Another key player in the mediation process was the Adriano Olivetti Foundation, which played a crucial role in promoting and coordinating the Nouveaux Commanditaires program in Italy, facilitating connections between public administrations and private patrons.[28]

Between 2002 and 2015, the Adriano Olivetti Foundation curated a total of nine projects within the program. During this period, several artists, operating both systematically and from a grassroots perspective—such as the Stalker collective—began to interweave artistic practice, understood also in its methodological dimension, with the dynamics of the city.[29] However, Stalker, with its interdisciplinary approach and strong reference to the Situationist practice of détournement, had already positioned itself in the 1990s as one of the few groups aligned with international experimental trends, standing as a unicum within an Italian landscape still deeply tied to traditional disciplinary structures. Ultimately, this collaboration with social policies initially served to raise important questions—to problematize an issue within the art system—regarding places (understood also as institutions) and education (understood also as methodology). Once the urban research field had been tested as an opportunity to develop true fieldwork, discussions began to emerge around the need for reference structures, funding programs, and educational frameworks. In other words, the idea of constructing an artistic system capable not only of collaborating with policies but of positioning itself as a key actor started to take shape. If it is true that history, in its unfolding, does not follow a strictly teleological, instrumental, or linear path, it is equally true that, by analyzing the relationship between social policies and artistic practices through the lens of funding calls, awards, competitions, and the subsequent creation of dedicated institutions, a certain political intent emerges. Although this process may have originated in a somewhat fortuitous manner, when observed retrospectively, it appears to have developed in alignment with the broader political agenda of other European countries—an agenda that, it must be noted, has led to the current state of affairs increasingly characterized by the dismantling of public governance, particularly in the domains of welfare and healthcare systems, now largely outsourced to third-party entities.[30]

Training Days. The Art, Heritage, and Human Rights Prize (2010-2016)

Once the urban context had been examined through the theoretical, administrative, and bureaucratic frameworks of regeneration projects, a second key issue emerges from the perspective of artistic practice: that of training. While the examples previously discussed involved established artists—recognized by the contemporary art system—working within the large peripheries of major urban centers, the following phase appeared to entail a reduction in scale. This shift concerned both the nature of artistic practice and the territorial scope in which it operated. It is in this context that the Premio Arte, Patrimonio e Diritti Umani (Art, Heritage, and Human Rights Prize) should be understood. As art historian and critic Enrico Crispolti has noted, examining competitions and prizes organized at the national level can offer valuable insights into the vitality of a given cultural moment. These awards function not only as symbolic recognitions—often at a national scale—but also as critical indicators of policy orientation and institutional positioning. Promoted by the association Connecting Cultures in collaboration with the Direzione Generale per il Paesaggio, le Belle Arti, l’Architettura e l’Arte Contemporanea (PaBAAC)[31] and the Fondazione Ismu (Iniziative e Studi sulla Multietnicità), the prize was awarded over four cycles between 2010 and 2016. In tracing the evolving relationship between artistic practices and urban policy—particularly in terms of territorial, social, and community engagement—this prize marks a crucial moment of transition. It signals a shift from a phase in which artists were primarily invited to collaborate with institutions and policy frameworks, to a new phase characterized by increased autonomy, where artistic practitioners were positioned to design, finance, and implement interventions independently.

This shift signifies the establishment of a specific reference system. The prize is also significant because it was designed for young artists (under 35), most of whom were not yet established within the contemporary art system, as well as for cultural institutions outside the logic of urban regeneration. In other words, emerging artists were invited to engage with local communities and cultural institutions beyond an “emergency” context, as seen, for instance, in Torregrossa’s intervention for The Gate project, allowing them to fully experiment with the possibilities of co-design. This approach enabled them to develop a range of soft skills—such as dialogue, active listening, and participation—which highlighted emerging methodological needs. Since, within the framework of the prize, artistic intervention was conceived as a practice of activation and participation rather than as a final artwork or product, establishing a national network of cultural institutions became essential. This network was meant not only to promote artistic interventions but also to serve as a reference point for young artists. The triangulation between institution, artist, and community was seen as a new and concrete possibility for artistic planning and intercultural heritage education. This ongoing exchange embodied the concept of ordinary praxis, aimed at “triggering concrete processes of change ‘in’ and ‘with’ the community, generating new relationships and awareness.”[32](Translated by the author) The prize’s objectives, after all, were to foster collaboration between artists and cultural institutions in developing projects that promote dialogue between individuals with diverse cultural sensibilities within specific urban or community contexts, generating awareness and new relationships; to encourage the use of artistic languages and creativity in addressing concrete spatial issues through the participation of citizens, communities, and institutions; to emphasize the importance of empowerment and cultural inclusion policies as ordinary praxis by institutions rooted in the territory—considered key factors for the sustainability, continuity, and widespread implementation of interventions. The key concepts, alongside community and territory, were tangible and intangible forms of cultural heritage, intercultural dialogue, and intercultural heritage education.

From the perspective of the different historical layers that contribute to constructing a broad and conscious narrative, as stated in the introduction, I want to include here a direct personal experience. I personally took part in the second edition of the award (2012) as curator of the project Diritti di Carta (Paper Rights)[33] presented together with artists Ruggero Baragliu and Paolo Scarfone. This experience marked my first real encounter with artistic practices engaged in a specific territorial context not directly ascribable to the contemporary art system, despite being partially funded by the Ministry of Culture. The objective of the Diritti di Carta project was to explore the tradition of handmade paper craftsmanship through collaboration with the Museo della Carta in Pescia (Pistoia) and its historic paper mill. The project we submitted for the award aimed to combine the production of handmade paper with the rewriting of new social rights. The paper, initially crafted by the artists, was to be distributed to the community of Pescia, which—in our intentions [we hoped]—would use it as a new Carta dei Diritti (Charter of Rights). Looking back on this project today, I recognize all the limitations of an art-based project design detached from its context. The transversal nature of artistic practice and its mediums led us to propose a symbolic collaboration which, in practical terms, had no tangible impact on the space or its community, given that the project had been conceived entirely by us in advance. Naturally, it was a first attempt—one that I now look back on with fondness rather than shame or frustration. The exchanges we had during the planning phase were highly fruitful and led me to activate a practical research line. At the time, I was in the middle of studies in Cultural Heritage at the University of Siena with Enrico Crispolti, and from a still-curatorial perspective, the idea of linking an artistic project—developed in a workshop-based and participatory manner—to the development of a territory seemed entirely natural to me. The major issues arose in our interactions with Baragliu and Scarfone. The latter, in particular, was not at all keen on involving the community in the creative process. We came from two different theoretical worlds, albeit reconcilable, as Baragliu and Scarfone—who were then attending the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome—were influenced (as was I from a curatorial standpoint) by a type of 1970s art much more aligned with concepts of authorship and individuality than with participation. One of our shared artistic “heroes” at the time was, in fact, Alighiero Boetti.[34]

From a social perspective, the 1970s were the years in which cultural workers began occupying spaces dedicated to culture itself beyond the institutional art world. That period had a strong impact on what would later be referred to as the season of the commons, eventually leading to the creation of a range of alternative spaces in Italy. The academic world, however—as often happens—moved according to different timelines and dynamics. Back then, my most direct references were the projects curated by Crispolti in the 1970s, and my artistic theory had not yet developed nor engaged with international experiences in terms of community-based or socially engaged practices. Essentially, me, Baragliu and Scarfone, came from the two separate worlds (theory and practice) and viewed each other’s fields with mutual skepticism. Our most heated debates—irreconcilable yet productive—centered precisely on these two ways of interpreting the same project. For Scarfone, it was a matter of losing artistic authorship, the fear of surrendering his artistic authorship: he did not want his technique to be shared, and participation had to remain a separate moment. From my still-not-practical perspective at the time, paper production was a pre-existing tradition, and the artistic contribution to the process did not represent an innovation, especially not for the residents of Pescia. The authorship that Scarfone saw in his work was an a priori obstacle to any attempt at opening up to collaboration. Conversely, my desire for participation relegated his work to a mere service-providing function. In my view, the artwork was not in the paper crafted by the artists but in the participatory process that would emerge from it. From Scarfone’s perspective, the work resided in his craftsmanship, not in the community’s involvement. As often happens when ideals and principles clash, our paths diverged when the project was not selected. One of the last things Scarfone said to me was, “But if you want to do things this way, why don’t you do them yourself?” Scarfone was right, and for that, I thank him. In a way, he taught me that if I wanted to build participation, I had to activate it myself without instrumentalizing the work of others.

Beyond our/my personal experience, the award served as a platform for organizing and developing highly interesting research projects, such as the one I discussed in a previous issue of FIELD, along with Elisabetta Rattalino, carried out by Nico Angiuli on the phenomenon of caporalato (illegal labor exploitation) in southern Italy.[35] Looking at the various projects submitted, it can be said that the prize’s purpose and objectives remained essentially art-based, with the actual possibilities of implementing shared practices or participatory design often confined to the final realization phase of the project. While supported by preparatory workshops intended to foster engagement and community involvement, the process largely remained under the control of the artist and the broader cultural system. Given its limited scope—both in geographic reach and financial resources—the Art, Heritage, and Human Rights Prize was ultimately accessible only to a relatively restricted audience, both within and beyond the art sector. Nonetheless, this limitation can be understood as part of a broader methodological trajectory, serving as a kind of training ground for artists and laying the groundwork for the institutional evolution that would eventually take shape in the fully structured format of the Creative Living Lab call. In fact, the establishment of the DGAAP—Direzione Generale Arte e Architettura Contemporanee e Periferie Urbane (Directorate General for Contemporary Art, Architecture, and Urban Peripheries)—in 2014 marked a significant shift. The very name of the institution seems to formally reflect the outcomes of those artistic practices that had initially emerged in a more “spontaneous” way through the complex urban projects of the late 1990s, alongside the emergence of more structured methodological training for artists

Institutional Learning: The Establishment of the DGAAP (2014)

With the establishment of the Direzione Generale Arte e Architettura Contemporanee e Periferie Urbane (DGAAP–General Directorate for Contemporary Art, Architecture, and Urban Peripheries), an institutional learning process was effectively completed. Within this process, the urban regeneration practices and policies implemented through complex urban programs—multi-actor initiatives tied to diversified funding streams at both the European and national levels—were consolidated and synthesized into the Italian cultural system. From this point onward, Italy began to develop its own internal policy on culture led urban regeneration, both semantically and economically. This transition can be described and summarized through the statement that accompanied the establishment of the DGAAP in 2014, which outlines the responsibilities of the Directorate: “to promote and enhance, support and increase, understand and preserve are the actions through which the DGAAP carries out its mission. The visual arts in their broadest sense (painting, sculpture, photography, video, installations, performance, etc.), architecture and design, as well as the redevelopment of urban peripheries, fall within its areas of competence”[36].(Translated by the author). I consider this statement particularly significant as it marks the institutional recognition of urban regeneration as a specific area of responsibility under a Directorate General—thus, a defined branch of the Ministry of Culture—placing it on the same level as visual arts and architecture. It is also worth emphasizing a terminological aspect within the statement itself: the reference to the “redevelopment of urban peripheries”.

In the context of urban planning, the concepts of urban redevelopment and urban regeneration should not be confused or overlapped, even though they are often used interchangeably. Urban redevelopment typically refers to physical interventions aimed at recovering or improving buildings, degraded or abandoned areas, and specific neighborhoods, with the goal of enhancing their appearance and functionality—without necessarily addressing the underlying social or economic causes of deterioration. It seeks to address the multifaceted challenges of disadvantaged urban areas through a combination of strategic vision and concrete action. On the other hand urban regeneration accounts not only for physical infrastructure but also for the social, economic, and environmental needs of the community, promoting a form of urban management that reflects the evolving demands of contemporary society. Given that the Ministry of Culture does not hold structural planning authority—unlike, for example, the Ministry of Public Works in the 1990s and early 2000s—one could interpret this as a blurring of domains, likely stemming from the porous boundary between cultural and infrastructural fields within urban design. This may also reflect a terminological ambiguity resulting from an ongoing process of development, and the consequent need for rapid adaptation and evolution. Regardless of terminology—despite its relevance for defining practical scenarios—the central role of culture in a broad sense, and of the Ministry of Culture more specifically, is further underscored in another excerpt from the same document: “[The DGAAP] promotes initiatives for the redevelopment and enhancement of urban peripheries, also through specific agreements with territorial and local authorities, universities, and other public and private entities”. (Translated by the author)

This marks a shift in the role of the Ministry of Culture, which has been primarily and historically devoted to the protection and promotion of what is institutionally recognized as cultural heritage. With the establishment of a dedicated General Directorate, the Ministry of Culture becomes the promoter and ultimate reference point for a key component of urban policies: regeneration. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the urban landscape was characterized by experimental fieldwork, with various artists exploring forms of participation and co-design in peripheral contexts. Over time, in the 2010s, attention shifted towards structuring calls and awards aimed at creating practical methodologies for new generations of artists. In 2014, this process further consolidated with the formalization of a well-defined reference system, wherein artists participating in calls and projects were recognized within a specific valuative, disciplinary, and economic framework.[37] This evolution marks a clear departure from the more spontaneous figures of the 1990s, who operated informally and experimentally in the context of urban planning. In its early years, the DGAAP promoted and supported various programs, events, and publications, many focusing on the recovery of areas on the periphery of urban centers, regeneration of unused spaces, and the creation of new social cohesion. This new direction began to permeate the cultural funding landscape of the period. Notably, in the second edition of the Culturability Call, promoted by the Unipolis Foundation—“Culturability. Spaces of Social Innovation” (2014/2015)—the term and perspective of urban regeneration were introduced. The call targeted projects capable of combining culture and creativity, innovation and social cohesion, promoting networks and youth employment, with particular attention to innovative proposals aimed at recovering abandoned or degraded urban spaces and creating opportunities for urban regeneration and development with a cultural dimension. Regarding this concept of re-semanticization and redefinition of cultural interests towards urban regeneration, the 2017 publication by the DGAAP titled Demix: Atlas of Functional Metropolitan Peripheries is noteworthy. In the introductory text, Federica Galloni, then Director of the DGAAP, states:

The debate on what should be understood today by the term ‘periphery’ is very active and current. For simplicity, we define peripheral those fragile places characterized by social and cultural marginalization, functional and service deficiencies, physical degradation—in short, places where there is a need to act with both urban and social redevelopment interventions. However, peripheries are also the places to bet on for the future of a country that has embraced the goal of reducing land consumption; they are the most flexible and resilient places, better able to accommodate the changes of contemporary society. The General Directorate I preside over does not have the competence to intervene directly in the drafting or modification of territorial governance tools; the challenge it embraces and promotes is to recover public heritage through cultural practices in the broadest sense of the term.[38]

The 2018 Creative Living Lab Call: First Edition and Direct Engagement

(It is worth noting that the initiative is now referred to by its Italian name, Laboratorio di Creatività Contemporanea, a change that should be critically examined in the current autarchic political climate. While many countries have always translated certain terms into their own language, doing so under the present government seems less a practical necessity or a semantic reconstruction and more a political directive.)[39]

The first edition of the Creative Living Lab was financed and promoted by the DGAAP in 2018, prior to its transformation into the DGCC (Direzione Generale Creatività Contemporanea) in 2019. The call for proposals aimed to synthesize the trajectory observed thus far, seeking to activate, from an art-based perspective, collaborations with local networks (associations, active citizens, territorial committees, cultural centers, social spaces, private entities) to foster cultural and social improvement in specific areas. In this context, unlike what was described in the founding act of the DGAAP, the term “regeneration” refers to social and cultural reactivation and recovery, rather than addressing a specific physical structural deficiency in a neighborhood or area [lack of housing, lack of infrastructure, public services, and transportation]. Here, regeneration is not guided by an external directive but is identified by the residents or applicants themselves. In other words, the urgency for regeneration is not predetermined by a specific urban planning initiative but is defined based on a transversal need for social inclusion—each periphery reflecting this necessity, as a social issue, understood as a need for greater cohesion, belonging, socialization, and participation, is a generalized condition. One of the main objectives of the call was to “create spaces for activities aimed at urban and socio-cultural regeneration, based on the principles of participation, integrated approaches, and sustainability. This is to disseminate methodologies for the implementation of micro-projects intended for communities, highlighting the importance of cultural and social aspects in redevelopment operations, also promoting the launch of new enterprises.”[40] (Translated by the author). The call was directed towards public and private entities active in the cultural and social field within a specific territory, aiming to create a network of experts not necessarily tied to the site of intervention. In this, the Creative Living Lab, reaching the culmination of a path intertwined between policy frameworks and artistic practices, sought to unite these two perspectives and the experience accumulated thus far.

Positioned midway between Nuovi Committenti and the Premio Arte, Patrimonio e Diritti Umani, the Creative Living Lab also opened participation to emerging artists. Another innovation of the call concerns the scale of intervention, adopting a ‘micro’ dimension, manageable even by associations accustomed to working with limited budgets. Another aspect demonstrating the institutional approach of the call is the composition of the applicants; participants were required to form a multidisciplinary group capable of analyzing the theme of regeneration in a multifaceted manner. This is indicated in the competition text regarding its objectives: “[CLL] aims to create participatory actions, realized by communities for communities, developed with the multidisciplinary contribution of cultural mediators such as architects, landscape architects, designers, artists, directors, videomakers, photographers, musicians, performers, writers, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists.”[41] In this multidisciplinary context, each discipline must be certified. Specifically, for the “artist” category, it is stated: “to be active in the specific sector and have at least one solo exhibition in qualified exhibition spaces. Experiences oriented towards regeneration and social integration issues will be positively evaluated.” This specification demonstrates how competence in the field of regeneration is defined through a recognition system, where the definition of ‘artist’ is given by activity within the sector through exhibitions in qualified spaces. The same applies to photographers, while for key figures such as psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists, it is required to have conducted research, participated in projects, or have publications related to the themes of the call. For all other professional figures, in addition to qualified and documented activity, adequate professional experience in urban regeneration and social integration issues is desirable. The predominance of the art-based matrix, in terms of recognition, demonstrates how the theme of regeneration has been re-semanticized within a properly cultural domain, as specific competencies are expressed in a rather generic manner, as can be inferred from this phrase in the call: “to have within the group at least one member with documented professional experience in the specific field of urban regeneration.”[42] Furthermore, following the example of the Premio Arte, Patrimonio e Diritti Umani, importance is given to training, as within the proposing groups, at least one member must be between 18 and 35 years old. From an operational standpoint, the call required the construction of micro-projects and training activities such as workshops, seminars, laboratories, exhibition, and educational pathways, with a program spanning six months. The resources allocated by the DGAAP for this first call amounted to €205,000, with a maximum of €34,000 for each project. There were six winning projects, evenly divided between northern and southern Italy.

Between Football and Art: Working in the Neighborhood

As with the Premio Arte, Patrimonio e Diritti Umani, the narrative thread of this account intersects with my direct experience, as I was selected to participate in the first edition of the Creative Living Lab (CLL) as an artist. I took on this role because, in 2016 during my Ph.D. years, I co-founded the collective Autopalo together with artist Luca Resta in order to practically analyze the artistic practices in urban space. The collective was conceived as a platform to investigate artistic practices oriented toward participatory processes, urban regeneration, and community art in broader terms. Over the years, we have worked with various media, including performance, video, and sound installation. However, a constant thematic focus has been the use of football as both an investigative lens and a tool for participation. In the first edition of the CLL, I collaborated with the Venice-based collective Gli Impresari, under the project leadership of Kallipolis, a cultural association focused on sustainable urban development. The project took place in the Ponziana neighborhood of Trieste, a district located just two kilometers from the historic city center, which could be more accurately described as an inner-city area. The neighborhood is characterized by a relatively high average age (51 to 64 years), with most residents living alone in public housing units managed by ATER (Agenzia Territoriale per l’Edilizia Residenziale). In retrospect, and in light of the current dismantling of social welfare structures and the redefinition of the public sphere, I have begun to reassess certain assumptions I had previously taken for granted. Within a broader neoliberal logic that frames public space and services as inefficient and obsolete, the strategic targeting of public housing for art-based urban regeneration initiatives no longer appears incidental. Rather, these interventions seem to reflect a moralizing discourse among both state and private sector actors that identifies socio-economic fragility precisely within those residential complexes historically built by the state to serve lower-income populations. These complexes often feature communal courtyards and spaces designed for social interaction and solidarity.

What emerges is a dynamic of symbolic displacement, wherein neighborhoods originally conceived as inclusive social environments are now problematized and reframed as “in need of regeneration,” thereby undermining the social and civic role of public institutions. This process has been identified in scholarly literature as part of a broader shift in urban policy. Leslie Kern, for example, in her work Gentrification is Inevitable and Other Lies, describes artists as “unwitting gentrifiers”, drawn into processes that ultimately advance speculative and exclusionary redevelopment agendas.[43] In this context, the CLL project in Trieste focused specifically on the internal courtyards of ATER housing complexes, framed as zones of social vulnerability. The artistic component formed one phase of the larger “Uplà-Lab” project, described as a format for reactivating residual urban spaces through play, using a workshop-based approach aimed primarily at neighborhood residents. Our artistic contribution unfolded in two interrelated parts: one participatory and community-centered, and another more symbolic and art-based. The former involved the creation of a neighborhood radio station (Radio Ponziana Errante), while the latter took the form of a sound installation (Il Posticipo). Thematically, football served as a resonant motif for the neighborhood of Ponziana, given its unique historical association with the sport. In the late 1940s, Yugoslav president Josip Broz used football as a political tool in support of expansionist ambitions toward Trieste, selecting Ponziana and its football team as symbolic of a working-class ethos compatible with socialist ideals. This led to the team’s split: one faction, Amatori Ponziana, joined the top Yugoslav league (Prva Liga), while the other, Ponziana Calcio, remained in Italy and played in Serie C, at that time considered as the semi professional level. The footballing history of Ponziana thus became the conceptual anchor of our project, serving as a narrative device through which to explore themes of identity, politics, and social cohesion.

Radio Ponziana and the Self-Representation of the Neighborhood

Beginning in November 2018, we conducted a series of interviews focused on the history of Ponziana Calcio and the ways in which the neighborhood was depicted and perceived, both from within and without. Our interlocutors were the classic privileged observers and gatekeepers often encountered in field research, primarily individuals working in the city’s social, political, and healthcare sectors. This generated a certain sense of discomfort, or predicament, in addressing the theme of social fragility from the perspective of those who, in some way, “administer” that very fragility. As a result, we decided to shift our perspective and, once again, football proved to be the most transversal element. From February to April 2019, we created a neighborhood web radio station that broadcasted from three different bars located in the area surrounding the old Ponziana stadium. The goal was to challenge and deconstruct the stereotypical image of Ponziana as a peripheral or marginal area. At the project’s conceptual stage, I was particularly influenced by the work of Inigo Manglano-Ovalle for Culture in Action, where representation was entrusted to the participants themselves through creative tools and methods that avoided the impersonality typical of ethnographic or documentary-style research. We designed the interviews as podcasts, allowing residents to narrate their experiences in their own terms, rather than through a conventional Q&A format. In a sense, we were the newcomers, and this framing underscored our outsider position. We aimed to develop a cultural device that was deeply rooted in the local context, while simultaneously being accessible and legible to a broader public. We drew inspiration from sports radio programs, creating a fully-fledged show in which the interviews served both to justify our presence in the neighborhood and to create a neutral space where people could speak freely, without feeling judged or treated as research subjects. Our direct and experiential reference model was the sports bar: that almost stereotypical place where every customer is a fan, and every coffee is merely a pretext to discuss the latest results of their team.

Each week, we set up a small but professional recording studio—complete with laptops, microphones, and headphones—on the tables of different local bars. The goal was to dignify the process and to generate trust and engagement among participants. Typically, the show lasted forty minutes and was divided into two segments: the first consisted of interviews with invited guests discussing their activities and relationship with the city; the second was an open-mic format, inviting anyone present to join the conversation. The name of the radio program, Radio Ponziana Errante (RPE), was inspired by a historical anecdote involving a group of Ponziana players who, during the Fascist period, refused to join the national football league and instead formed an independent team known as the Ponzianini Erranti. ‘Erranti’ can be translated as ‘the wandering ones,’ which at the time reflected the team’s condition, as they did not have an official home ground. Our radio station was a traveling, wandering program, broadcast from local bars, podcasted on Radio Ca’ Foscari (Venice University), and aired on Radio Fragola every Monday and Saturday from February to April 2019.[44] The radio project allowed us to reconstruct the live commentary of what locals remembered as the most important match in Ponziana’s history: the 1974 derby against Triestina. This imagined radio commentary—reconstructed through newspaper archives and interviews with former players, as no audiovisual recording existed—formed the basis of a large sound installation we later staged at the old Ponziana stadium. If I were to evaluate the project strictly in terms of artistic quality and technical execution, I would consider it a success—its outcomes were particularly relevant within an art-world context. However, I find it harder to assess the project’s social impact, which I believe fell short despite promising beginnings.

On one hand, I could take comfort in the ephemeral nature of the project, aligned with the call’s stated aim to generate short-term cohesion. On the other, I continue to feel a sense of discomfort—an unresolved tension between artistic voyeurism and social responsibility. This ambivalence has both objective and subjective roots. From a structural perspective, the project’s failure to “spread methodologies for the creation of micro-projects designed for communities” is particularly evident. Despite real interest and momentum around formalizing the radio station as a lasting initiative, it received no institutional support. In the final weeks of the project, a collaboration was initiated between Kallipolis and the University of Trieste to set up academic internships aimed at embedding the radio station in the local community. A physical location was identified for this purpose. Unfortunately, bureaucratic constraints and the inflexible timing of the call made such a longer term project difficult to sustain. By the time the collaboration was officially recognized in May—after the project had ended—funding had been exhausted, and Kallipolis’s involvement ceased. From a subjective and personal standpoint, I would not go so far as to call the project a failure, but I do consider it problematic—particularly in terms of its human implications. The radio did not merely serve as a tool for investigation; it confronted me with what has been described as a “sentimental speculation,” especially in the process of elaborating and later writing about the project.[45] The experience of the radio, by allowing participants to speak about themselves in different and unexpected ways, enabled the development of a trust-based relationship with the neighborhood. It became an act of “taking voice” rather than “giving voice”—the latter implying a hierarchical stance and a gesture of permission.

This openness to self-narration—whether alternative, transformative, or at times exaggerated—led, over those months, to the formation of a micro-community, a small circle of trust that gathered across several bar to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the microphone and, without falling into paternalism myself, to feel like protagonists of their own stories. Several people we encountered at the bar tables expressed a deep need to be heard, which I found overwhelming, as it challenged the conventional role of the passive artistic subject or the performer tasked with executing a series of movements. I was working within an artistic framework, but the material I was dealing with was not inert—it was human. And one cannot suddenly become a social worker or cultural mediator simply because the current trends in contemporary art have shifted toward the social, the participatory, and the dialogic. Even now, six years later, I often return to this project in reflection, as it provided me with direct access to, and practical understanding of, the mechanisms that shape ministry-led urban regeneration initiatives rooted in culture. Through this experience, I was able to formalize a practice-based research methodology—something rarely taught in art history programs or fine arts academies—which has enabled me to reach more quickly the core of the issues at stake. These issues, in their transdisciplinary and trans-territorial nature, reveal many of the very problems I continue to face in my own work. Yet this, too, is a form of institutional learning. The real question is: in which direction is this learning taking us?

Creative Living Lab: Adjustments, Learning, and New Openings