Diagrams and Dreams: Stephen Willats’ Utopia

By Oliver Noble

‘The pinnacle of utopia may rise right up through the clouds but the soles of its feet rest squarely on solid ground.’

—P.N. Sakulin, 1913[1]

In Stephen Willats’ work, utopia is upheld by a faith in humanity. Willats’ art rejects the idea of normal protest; discussions in hallways replace slogans in the streets and children’s graffiti replaces bricks thrown at police. Instead, what it offers is both a catalogue and a guide to a social revolution of day-to-day life.

The dream of utopia is the lifeblood of this catalogue and guide. It is what raises Willats’ practice out of its artistic context and allows it to escape from the pure conceptuality of its models. Without the utopia that a viewer registers in Willats’ work–a world where art has the power to change people, people have the power to change their world and the world has the ability to throw off its hierarchical structure–his art would lack a pivotal component of its vitality and potential.

This article therefore looks at Willats’ art through the frame of utopic aspirations and thoughts. Aspirations and thoughts that for Willats straddle an ill-defined boundary as he both holds a conception of how the world should be and is committed to allowing others to choose their own conceptions. At the heart of the article is a study of Willats’ Vertical Living project of 1978. Using the project to analyse the ethical and practical dilemmas in Willats’ work, the article is split into three threads. It first studies the artist’s formative experiences with Roy Ascott and cybernetics. Second, it considers Willats’ community-driven works of the 1970s where the focus is on permitting others freedom. Finally, it gathers the lessons from his earlier practice into a study of the works that reveal Willats’ own conception of utopia: his subculture works of the eighties.[2]

Roy Ascott and Cybernetics

‘Socialists and scientists together can make their dreams a reality’

—Judith Hart, Member of Parliament for Clydesdale, 1963[3]

‘The most extensive changes in our environment can be attributed to science and technology. The artist’s moral responsibility demands that he attempt to understand these changes. Some real familiarity with scientific thought is indispensable to him.’

– Roy Ascott, 1964[4]

The 1960s in Britain represented a decade of political flux. In Westminster, the Conservative government was thrown out by Harold Wilson’s new vision in which science and socialism would work hand-in-hand. On the streets, Britain’s artists took part in the CND marches that brought together an explosion of New Left organisations in the country. However, displaying an independence from both party politics and the artistic community that would characterise his career, Willats held himself apart from these environments.[5]

Instead, the artist’s early politics were discovered not on the streets but in the art workshop. Between 1962-63 Willats participated in Roy Ascott’s revolutionary Groundcourse at Ealing School of Art. A period after which he taught alongside Ascott at Ipswich Community College between 1965-67.

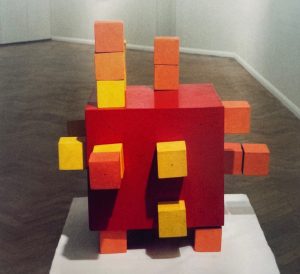

Representative of this period, in Colour Variable No. 3 (1963), Willats offers to a viewer/participant an opportunity to arrange a collection of small, multi-coloured blocks around the body of a larger red block (fig. 1). Lego for adults which both plays on the kinetic art Willats had experienced during his time working at the Drian Gallery, the piece also reflects the focus on interaction and individual creativity that defines Willats’ practice.[6]

1963.

Ascott had been working off the same principles for several years before 1963. A re-arrangeable work such as Change Painting (1961), although in many ways very different, shares the same principles as Willats’ art–principles at that time largely unaccepted in Britain (fig. 2).[7] Although Willats’ personal style differs significantly from Ascott’s, Willats’ approach to art was evidently significantly inspired by his teacher. In particular, the centrepiece of Willats’ kinetic works–their mechanism of interaction–seems to have been lifted from Ascott. For both, this mechanism can be split into three steps: first, the work offers to the participant a stage to make their own, to organise and define. Second, the engagement with the works becomes an existential statement on the part of the actor and encourages an evolution in the participant’s consciousness towards a self-determined control. Finally, this evolution of consciousness develops in the subject a new form of engagement with their environment and art therefore becomes a ‘force for change in society’.[8]This mechanism would develop into the foundation for all of Willats’ future work.

Through the Groundcourse, Willats was also introduced to cybernetics.[9] Merging fields such as information theory and psychology, cybernetics looked to create artificial models that would replicate natural systems. Reflective of the interactivity of his kinetic works, Willats was particularly inspired by the second-generation cybernetics of Gordon Pask and Stafford Beer which was characterised by its reflexive turn. Like Willats’ inversion of artistic creation through participation, the concept of control was inverted by the second-generation cyberneticians into an activity of self-determined freedom.[10]

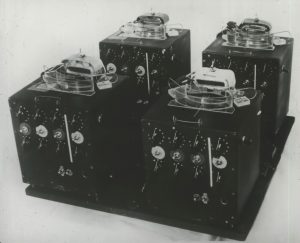

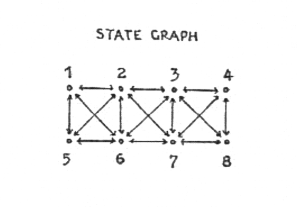

Begun in 1968, the Homeostat Drawings are the most evident artistic example of this cybernetic influence (fig. 3). Inspired by Ross Ashby’s electronic homeostat, the flat plane of Homeostat Drawing No. 1 reflects a non-hierarchical model of society conjoined through a common language (fig. 4).[11] Pushing on the straight-lined boundaries to convey the infinite expansibility of the system, the tightly organised rectangles also retain human imperfections in their gently sliding vertical orientation and their deviating dimensions.

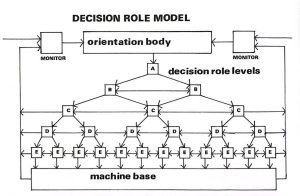

For Willats, life before the 1940s was defined by an industrial-mechanical economic base which determined a hierarchical superstructure–a superstructure modelled by Willats in fig. 5.[12] In contrast, the contemporary era’s new communication systems offered the potential for a transformation of authoritative transmitter-receiver relationships into mutualistic relationships and through this, the development of society into a mutualistic space–a proposition that is visualised by Homeostat Drawing No. 1 and preceded by a work such as Colour Variable No. 3. For Willats, ‘the homeostatic network informed a new vision of society’ freed by technology; one in which every individual would have an opportunity to speak for themselves.[13]

Even at this early stage you can sense the centrality of diagrams in Willats’ work. Aside from the sculptural pieces, the majority of Willats’ pre-1970s output are drawings on paper in the manner of the Homeostat Drawings. More than visual tokens, they act as visual evidence and enjoinders to realise the society they display–like a mix of an architectural mock-up and a mathematical proof. In their frequency, they evidence Willats’ deeply analytical approach to art.

This same mindset is attested to by the logical rigidness of Willats’ three-part consciousness-changing mechanism previously described. It too has a diagrammatic form, with a straight line of implication joining the three steps in an inseparable chain. The era of the 1960s was a fertile period for such analytical mindsets. Not only was it a time filled with the utopian longing where theory often took centre stage over practice, for example with the New Left, but the computer age was beginning to get into its stride. While Judith Clark and Roy Ascott were extolling the centrality of science to both politics and art, new fields such as modern control theory were providing the basis for the computers that took Apollo 11 to the moon.

Cybernetics was a subfield of control theory and had its fair share of dreams. The inspiration for Willats’ applications of the homeostat came from Gordon Pask, in whose laboratory he worked, and Stafford Beer who had developed Ascott’s blueprint into a reference for non-hierarchical and self-organising groups.[14] Expanding the homeostat into a model of society, Pask had applied it to learning systems for small groups and at its height, Beer would even form it into a vision for the socialist state of Salvador Allende’s Chile.[15]

Although Willats shared in Beer’s belief in the power of the homeostat, Beer’s project was in a sense the antithesis of Willats’ utopia. Even if his mindset was deeply rational, his politics leaned towards anarchism; an outlook diametrically opposed to the vision of an all-powerful, all-seeing Marxist state. Willats’ writings make occasional references to socialism, while his friend, Jane Kelly, has placed him firmly into its ideological sphere but he on several occasions has rejected the imposition of dogma onto his practice. If the socialist connections are there, one explanation might be the harmony between the New Left and the anarchist movement during Willats’ formative years; a harmony reflected in the slogan ‘ban the bomb means ban the state’.[16]

Willats’ anarchism interest began in the 1960s–the decade in which the movement became middle-class–and leans towards Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s strain of anarchist mutualism.[17] Like Proudhon, Willats espouses a utopian society that is non-hierarchical, made up of federalised communities and centred around individual potential. Unlike other strains which push communal redistribution, at the heart of both Willats and Proudhon’s visions is that a person’s individual activity and creativity is the truest expression of freedom.[18]

The political aspects of Willats’ art also represented a break from the artists who had come before him. If Willats’ diagrammatic aesthetics and theoretical inclinations owe a debt to the British/American conceptual art of the sixties, there was a clear break between them. Most conceptual artists’ work was founded around commercial galleries and institutional settings–between 1968 and 1970, Richard Long had seven solo commercial shows. And even if their other exhibitions took the form of a published magazine or such, there was still the assumption of them being received within the rarefied air of the artistic community. In summary, where the art was political, it was primarily institutionally political. What was–and still is–radical about Willats’ work was his connecting the dematerialised art of the conceptualists with the new class concepts of his era and his situating of this art within the communities he was working with.

Other artists were wrought in a similar image from the currents of the seventies. Practitioners such as Conrad Atkinson in Strike at Brannans put their art at the service of working-class concerns, gay artists fought for the visibility of their issues, and feminist artists went into the homes and factories of working women to document their everyday lives. For many, their final artworks would also be displayed in settings apart from the classic gallery space–Women at Work by the Hackney Flashers travelled widely to colleges, libraries and town halls. Such practices implicitly recognised that for a dematerialised concept of art to survive without becoming barren, it needed to be underpinned by a politics. Yet Willats was one of the few to go one step further; his ambition was for an art that could enter into social environments and become a tool for these groupings to improve their daily lives–this approach was set to be the defining feature of his projects of the seventies.

Ideology and Community

‘Anger is building up within the grey concrete walls’

—Stephen Willats, 1982[19]

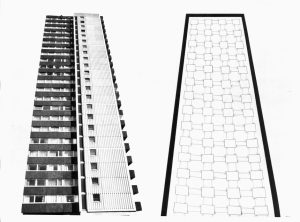

Symptomatic of a decade when planning could change the world, in 1969 Gordon Pask described a cybernetic future in which architecture would act as ‘symbolic control program’ to regulate inhabitants’ lives.[20] By the mid-1970s however, the tide had turned on community housing and such a thought had become anathema. There developed a widespread perception that social housing estates were breeding places for antisocial behaviour and their status as symbols of utopia was exchanged for marks of domination–1975 saw published J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, followed two years later by the English translation of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish.

In this context, Willats–a child of the rapidly-developing London suburbs–inverted Pask’s conception of the semiology of the city to describe what he would label ‘The New Reality’.[21] Informed by a reading of Charles Kiesler and Sara Kiesler’s Conformity and possibly also the essays in Marxism and the Metropolis, Willats’ conception of ‘The New Reality’ was an impressive semiotic study of the reified role of buildings and objects in the creation of an enforced ideology.[22] In an environment such as a council estate in which the ‘evolution of a social environment’s rule structure … are largely undetermined by its members’, the signs of modern architecture enclose the individual in a structure of symbols that strips their freedom.[23] The time-saving designs of the rooms deny personalisation, the objects of consumerism become jailors in the service of conformism and the great monoliths of concrete sixteen stories high become prisons–utopia becomes dystopia.

Opened in 1974 by Harold Wilson, Skeffington Court was the setting for Willats’ first project in a single tower block and the work produced, Vertical Living (1978), was one of his first projects dealing with both ideology and community. The basis for Willats’ community work however is found in Willats’ Man from the 21st Century (1971). In this project he and his students–he was at that time teaching at Trent Polytechnic–worked with residents in two local areas; questioning and analysing their responses to their environments.[24] This work represented a ‘going back to zero’ for Willats to engage with the pivot from art’s 1960s obsession with phenomenology to being at the heart of the politicisation of 1970s art.[25] In Britain this pivot was partly a reaction, a reaction to the cultural ‘moral panic’ of the 1970s. Willats’ response to this panic was his community engagement and several other community works followed Man from the 21st Century, each one developing in terms of complexity and methodology. In 1972 with The West London Social Resource Project Willats began taking pictures of the personal items of participants to include in his works and in 1973 The Edinburgh Social Model Construction Project made use of a computer to analyse participant responses.[26]

This faith in community work paralleled an explosion of interest in the concept of community in Britain. The foundations for this interest had already been laid before the 1970s by factors such as the rich genealogy of British documentary photography and the bequeathal of a politics by the New Left where personal liberation could only come about through social liberation. However, the decade of the 1970s saw this interest crystallised: the term ‘community art’ came into use, magazines such as Friends encouraged a fight for ‘community control’ and the Government launched the Community Development Projects to create localised forms of (governmentally-approved) political structure.

The period of 1978-80 marked Willats’ emergence out of this context into becoming one of the faces of British conceptual art. During these three years, Willats had solo shows at the Stedelijk Museum, the Whitechapel Gallery, as well as the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford. And in 1979 he exhibited in the group show Un Certain Art Anglais at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. The most representative work of this period is Vertical Living–a work which operated in two stages.

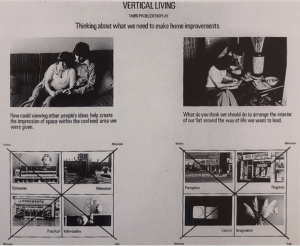

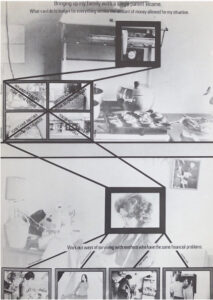

In the first stage, Willats collaborated with seven residents. The tower block having only recently opened, Willats would visit these residents in their apartments, explain to them the concept of the artwork and discuss with them how they were adapting to their new environment. These collaborations led to the production of a series of ‘problem boards’ which were put up sequentially on alternate floors of the tower, on alternate days, for residents to respond to.

‘What do you think we should do to arrange the interior of our flat around the way of life we want to lead[?]’ asks a young couple in the third problem display (fig. 6).[27] Reminiscent of the flow diagrams of information theory–although also possibly taking inspiration from the juxtapositions of text and image of Victor Burgin whom Willats had taught alongside–out of the general statement at the top of the work leads two parallel series that go: picture, question, diagram.[28] The statement contextualises the picture, the picture provides a reference for the question and the diagram offers up a model for the other residents to use to analyse the problem. The most complex part of the board, the diagram, consists of four images taken by Willats from within the residents’ environments, on top of which has been superimposed a black diagonal cross.

Taking both its visual and theoretical cue from Gordon Pask’s ‘phase diagrams’, the diagram offered its images and its axis titles of identity, motivation, behaviour and code as a sort of map which a resident could utilise to structure their response to the question (fig. 7).[29] The four images were chosen by Willats to be both general and impersonal in order to find twins amongst what the artist has labelled–borrowing from the sociologist Basil Bernstein–the residents’ ‘restricted codes’.[30]

For Bernstein, language codes are both socially determined as well as the necessary mediator between an individual and reality.[31] Willats’ theory develops from this foundation so that when a resident discovers a twin of their own code in the artwork, not only is the art enabling them to view their own society, it is also permitting them to consciously externalise their relationship to reality.[32] Moving from descriptive to prescriptive, and mirroring the work of a psychologist, the visualisation of the problem can then be utilised as a base for the resident to learn from and move towards a new, personally-chosen, utopia–a process Willats slightly unsettlingly labels ‘social evolution’.[33]

The second stage of the work involved about one-third of the residents being given a ‘Project File’. On alternate days over a fortnight the residents would respond–via Willats’ Bernsteinian process–to the most recent problem board that had been put up. These responses were then displayed on their respective problem board: the material counterpart to the symbolic questions of the visual works. On the day of the response collection, a new problem board would be put up on a higher level of the tower. In this way, the boards slowly moved up the tower, encouraging residents to explore areas previously unvisited.

Through these two stages the artworks became localised forums in which residents could communicate with each other and the tower block itself was transformed into a modern-day polis–an idea visualised in Conceptual Tower Series No. 6 (1985) (fig. 8). Politics was introduced to the tower both as an excuse for the birth of society as well as an opportunity for organised action. Willats’ hope was that his artworks offered the residents a place to come together to communicate with each other and that through communication residents would form a mutualistic society to fight their own battles against ‘The New Reality’–an assertion that the real professionals of life were the ones who lived it not society’s experts.

As stated earlier, right from the start there was a strong analytical impulse behind Willats’ art and in Vertical Living it spreads to its full extent. It’s in his methodical theory of consciousness changing; it’s in the design of the project (the final article even includes a diagram that lays out the different stages in flow map form); it’s even there in Willats’ writing style. The final article reads like a scientific paper with well-organised sections for each stage of the project and inside of that, quotes from participants and project operators. Taken together, one gets the impression that Willats’ diagrams are more than just visual aides, they are a central frame through which he envisages his practice.

Laying aside the potential ethical issues of such a radically rational approach in community art for now, there are also clear practical implications. While a belief in the applicability of diagrams might help in providing a set structure around which Willats can build his project, a refusal to account for variety and different experiences is to expect conclusions that will never be fully borne out in real-life scenarios. Even where there is a level of reasonableness in each of the stages, when they are then joined up together in an indissociable chain with each requiring the link beforehand to hold, casuistry comes into the frame. The image of the homeostat in Conceptual Tower Series No. 6 has a wonderful clarity and an inspiring advert-like aspect, but to expect it to hold within a community proper might be called optimistic in a positive reading, problematic in another.

Another issue: how can one expect to learn from the errors of a project, if they assume from the start its logical sureness? For example, while in the final analysis, the tone of the participant’s statements is chatty and personal, Willats’ general tone is matter of fact and unemotional.[34] With the regular use of terms such as ‘thus’ and ‘therefore’ and a general lack of cautioning terms, it often reads as much like a declaration of his theory as an evaluation of it.

Taking all of this in mind, the question is left hanging how successful Willats was in achieving his goals for Vertical Living. He himself avoids the question with the only follow-up activities being interviews two months after the project’s end. That the residents made new problem boards after Willats had removed his might be seen as an indication of success.[35] However, participants have been more ambiguous about the effects of the project and the diagram portion of the works, the part that contains the bulk of Willats’ theoretical faith, was evidently largely ignored.[36] One is left to wonder how much Isaac Kramnick’s statement that ‘what replaces politics for the anarchist is either education or theatre’ is also applicable to Willats’ work.[37] A belief that a one-month group art project can do the work of a year of therapy certainly leans closer to the theatrical than the realistic. As Lewis Biggs, one of the ‘project operators’ of Vertical Living, described the impression Willats gave: ‘he came across as a wayward self-taught social scientist … The Joseph Beuys of West London.’[38]

Even if Willats’ work didn’t reach the heights envisaged for it, there were clearly many positive aspects. Here is a collection of participant responses: ‘Sometimes we saw neighbours bringing their friends to have a look around and we would have a little chat’; ‘A lot of the response did bring out what other people thought… We could understand how they felt at the same time as worrying about our own problems. It was a vast response really…’; ‘I really thought that someone was living here’; and ‘For old Mrs. Morran downstairs I should imagine it was one of the greatest things that ever happened to her for years’.

There is a definite sense that most residents who took part enjoyed the experience. One might recognise issues, but it would be patronising to discount the quoted residents’ experiences. ‘Fifty percent were really thinking [about their responses]’ stated one participant which if correct would be a strong engagement rate. And in the final takeaway, the facts of the matter that Stephen laid down are true: the tower block of the era did compartmentalise life to such an effect that an artwork that brings people together must necessarily have some positive effects, even more so one that encourages people to come together in a communal spirit.

Yet clearly there is a gap between this statement where at most the community artwork encourages people to come together and one such as ‘… the seven areas of attention led participants from a descriptive analysis of their situation, to the notion that they could re-order their lives as a community’.[39] How is one meant to judge an artwork where the conclusions at stake are at such a distance from their realised forms?

Subcultures

I am an anti-Christ

I am an anarchist

Don’t know what I want

But I know how to get it

I want to destroy the passerby

‘Cause I want to be anarchy

—Sex Pistols, Anarchy in the U.K., 1976[40]

At this stage, the image that might have been gained of Willats’ mind is that of one divided between the inputs of the participants and his already set processes. Often it is the latter that wins out. In one project analysis, he described participants as being ‘encoded’ into the artwork and elsewhere he writes: ‘Pursuing the direction of the consciousness embodied in the work, it didn’t draw any conclusions for its audience, and in doing so respected the state of mutuality integral to its operation…’.[41] ‘It didn’t draw any conclusions’ –it is as if the artwork itself has emerged as a machine-like entity.

From his early kinetic pieces, to his later projects, Willats’ art is defined by its purpose of providing its participants a space to make their own choices. But when the work grows into an independent and intensely rational operator that is intended to manage the interactions and consciousnesses of individuals, the ethical issues come to the fore; particularly with a practice based in community art.

Viewed now, we might gloss over such issues considering the utopian aspects of the projects. Nourished on cybernetic theories though, there really was a belief amongst the artists of the day that an artwork could alter someone’s consciousness. Willats for example used to discuss the potential moral issues of his works with other artists due to the fear of them being too powerful controllers of people’s consciousnesses. Look again at Conceptual Tower No. 6 through this light and the homeostatic diagram enclosed in the firm walls of the tower might present a more controlling spectacle than originally envisioned.

In Vertical Living, what is notable in the project displays put up throughout the tower is the lack of positive questions like ‘what is good and we should be proud to continue with?’. As one participant in Vertical Living commented ‘Our friends don’t really make a lot of the project, I suppose unless you live in a tower block you don’t realise the difficulties and the pleasures of it, because there are pleasures as much as there are difficulties.’ Yet in Willats’ final written analysis, the pleasures are dwarfed by the difficulties, and the ‘devious’ questions that were asked–as one of the participants termed them–to an extent pre-framed the participants’ answers to suit this conclusion.

Assumed as axiomatic from the beginning, this declared opposition between the lives of the participants and the architecture of the towers lies at the heart of Willats’ ethical dilemma. As he wrote in relation to another project: ‘Within the work the physical reality of the estate is seen as a symbol of the dominant authoritative aspirations of our society, while the daily lives of residents are viewed as a counter consciousness of mutually based interaction.’[42] The work here is envisaged as a moving battlefield with the repressive societal-defined architecture on one side and the potential counter-utopia of the residents on the other–an approach that by nature excludes the full range of participants’ thinking.

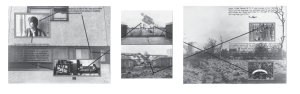

Yet, just as how we saw with Vertical Living there is the opposition between utopian goals and indisputable practical benefits, there is also a laudable ethical aspect to Willats’ practice. Central to all his work, and whether it is a heritage of his anarchist leanings, the socialist-humanism of the British New Left or even feminism, is a focus that always boils down to the individual. It is implicit in Vertical Living and explicit in other works such as Living with Practical Realities (1978) and Single Parent Family (1978). Single Parent Family for example situates itself in the context of the powerful feminist movement of the 1970s (fig. 9). The work visualises a de-reification from an object-defined environment to a person-defined environment through the activity of problem-solving. Here, problem-solving becomes an existential statement that marks the mother’s control of her situation–a mirroring of Ascott’s 1965 remark that ‘to control one’s environment is to assert one’s existence’.[43] As this works attest to, in Willats’ vision for society, the personal is always the political.

There is clearly an odd dichotomy in Willats’ works–they focus on the individuals, yet the pieces themselves are deindividualized. From his projects to the finished artworks he creates, there’s a push and pull between messy radicalism and clean lines that blurs the idea of any utopian ideals one might attach to his practice–can the anarchistic ideal really be achieved when everything needs to be joined by straight arrows?

The 1980s marked a turn in Willats’ practice. If the works of 1960s and 70s are defined by Willats’ building up his theoretical approach around the artwork as a potential consciousness-changing agent in society, the pieces of the 1980s move towards presenting a more personal vision of the goals of that change.

Dirt and a battle for control, those are the foundations of Willats’ best known work: Pat Purdy and The Glue Sniffers Camp (1981) (figs. 10a, b).[44] At the time, Purdy was a young resident of the Avondale Estate, a five-minute drive from Skeffington Court. Continuing the mode of the Skeffington works, in the left panels of the triptychs Purdy questions her relationship to the estate environment. In the right panels however, Willats places images of objects found in a wasteland Purdy would visit when younger, locally called the ‘Lurky Place’. The central panel displays the journey between these two situations. Inverting the visual and moral code of Hieronymus Bosch’s great triptychs of heaven and hell, two lines starting from a picture of Purdy interweave to form a route for transformation. Beginning in the false-heaven of typed lettering and acceptable society the lines wind rightwards, ending up in the lawless lands of the ‘Lurky Place’ and the freedom of handwritten text.

Echoing the Situationists, the two black lines in the work map a détournement of the modern city-scape–a re-mapping that Willats signposts through objects.[45] As Willats describes it, the transformation of these objects represents a personal action of revolt against the dominant ideology.[46] For Purdy or a friend to take an Evostick into the wasteland for glue-sniffing was to transform it from its socially-accepted function as a sticking agent into an agent of freedom. This transformation Willats labelled the activity of a ‘counter-consciousness’–a term used in 1972 by Herbert Marcuse.[47] The ‘Lurky Place’ was therefore a counter-space created by a counter-consciousness and, mirroring both the Situationists and Marcuse, was defined by its role in the freeing of desire and creativity.

To Willats, the ‘Lurky Place’ represented an outgrowth of the punk movement he had come across during his Skeffington Court project.[48] Excited by its anarchist principles, Willats became obsessed with punk/post-punk, visiting clubs with the American artist Dan Graham and buying all the 45 RPM DIY single records he could at Rough Trade.[49] In many ways however, punk was the antithesis of Willats’ finely drawn lines, diagrams and spotless production quality. It revolted against the stuck-up British establishment and one can only imagine what the punk movement would have said about Willats’ works.

It is not just the looks of the works it would have rejected but the ideas behind them. As already noted, it is difficult to escape the troublesome aspects of distance and control in Willats’ pieces. These aspects add to the feeling of sociological experimentation in his projects–Willats’ readings reveal a fascination with experimentation methodology–and amplify his art’s problems with consent: a participant has described how Willats made artworks using her image without her knowledge, as well as included her quotes in a work despite her displeasure.[50] As an art commentator of the 1970s wrote about Willats’ practice: ‘It is condescending and manipulative, experimenting on the subjects … as if they were rats’.[51] However, middle-aged and arriving to punk in 1977 when it was already a ‘parody of itself’, Willats was possibly too late and too culturally distanced to realise the contradictions of his punk fascination.[52]w

Placed in context, Willats’ interest in subcultures was one example of a more general trend of the era. In 1979, Dick Hebdige published Subculture: The Meaning of Style and the wider grouping at Birmingham University’s CCCS was at the forefront of creating the Cultural Studies field. That’s not to say Willats was just a follower of these intellectual flows. At the centre of Willats’ interest from the start was an interest in the political aspect of everyday objects and in this he was at the forefront of thought–Willats’ The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour was published in 1973, a year before Michel de Certeau’s L’invention du quotidien. Willats might have taken inspiration from the CCCS’s work but at the same time, one suspects that they were working along similar lines from an earlier point–a person keen to interrogate everyday objects and class structures through aesthetic approaches is likely going to end up with an interest in subculture movements.

If Willats was too late for punk though, post-punk in contrast offered a movement for him to be on time to. Across the UK a deluge of DIY clubs and record labels broke out–a materialization of Willats’ community ideals. The club that epitomized these cultural developments for Willats was the Cha Cha Club which he had been introduced to through chancing across an ex-student in Earl’s Court.[53]

Made in collaboration with Scarlett Cannon and Michael Hardy who ran the club night, Willats’ monumental Are You Good Enough for the Cha Cha Cha? (1982), now in the Tate collection, visualises the birth of a society (figs. 11a, b). Handwritten text is scrawled chaotically around the focal points of the two circles reflecting a society defined by its rebellious anarchy.[54] Likely emphasising the constructivist inspirations in the New Romantic style, the work mirrors a contemporary piece Between Day and Night No. 1 (1982) in echoing Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) (fig. 12).[55] The thin-lined arrows pierce the black circles from their positions in the white circles: white circles that could be modelled on either of a stop sign or a pill.

At the same time, unknowingly echoing Alexander Herzen’s words: ‘The moonlight of fantasy’, the symbols and objects of the subculture are split by the counter-conscious transformation from the white of the day in one half of the panels to the freedom of the black night in the other half.[56] Re-affirming Willats’ 1960s interaction theories, the viewer is invited into this darkness. Forced to get up close in order to read the small text, the viewer is engulfed by the black and yellow hatching surrounding the panels. They themselves enter the blackness of the club interspersed with the bright flashes of yellow strobes.

In Are You Good Enough… there was no participant to be ‘evolved’ as in the earlier community works–works about which Cannon has described her discomfort.[57] Instead, the piece is extremely personal. With its affixed objects–objects Willats collected off the dancefloor during the club nights–the work stands as a shrine to the vision of society Willats had spent twenty years dreaming of.

Defined by its otherworldly outfits, its anarchistic structure and the electronic melodies of bands such as Visage, the club represented for Willats an electric Eden: ‘a new culture founded on informal networks that were contextualized in their creativity to the sensibilities and priorities of participants’.[58] At the same time, these clubs were to Willats more than his term ‘parallel world’ implies and more than Henry Berger’s ‘withdrawal from the actual environment’ makes utopia out to be.[59] They were places for ‘counter-consciousness’; for action and for protest in Thatcher’s Britain.

At the centre of Willats’ practice is a dream of an ideal society that is non-hierarchical, mutualistic, electronic, totally self-organising and made-up of small communities. The Cha Cha Club came closest to this conception, but even here only in a transient and localisable form. The faith in an evolution of this community into the structure of a complete society–an evolution Willats believes can happen by agreement alone and without conflict–is clearly utopic.[60] And as an anarchist’s utopia seeps through into their activity, so it does with Willats also: his work will always fall short of its goal to restructure people’s consciousness and the faith in technology on which he bases his work seem less and less realistic every day.

Placing these utopic ideals against his previous works such as Vertical Living, Man from the 21st Century, or even the early diagrammatic pieces, you realise that Willats’ art is much more personal than might first be assumed. With its conceptual aesthetic and community focus, the first thought might be of a practice that is delinked from the personality of its producer. However, Willats himself almost always emerges as the central feature. His work is fully defined by his way of thinking.

Often this is the cause of the sense of dogmatism in his work, yet, in that his mindset is indissociable from his utopic goals, it also plays a vital aspect in its many positive qualities. For one, it provides him with a structure around which to build an impressive theory of artistic practice. But also, from his belief in the potential of his work, you sense that Willats gains the concomitant desire to make it happen–for sure such a manner can easily move in the wrong direction but the foundation of any better future is always first a hope in that future.

And how should we assess the value of the ideal society that Willats envisages? On one hand, the cybernetic aspects are always going to lend any possible future a problematic, overly-analytic sense–the dystopian writings of Aldous Huxley or Yevgeny Zamyatin being the limit point of this methodology. A society founded on diagrams and psychological theory is naturally going to end as overly-structured, and even controlling. On the other, a future based around individuals’ ability to recognise and change the structures of life that limit them, is vital to any utopic aspirations.

Maybe here is where the value of Willats’ art is greatest. What it presents is the possibility of using aesthetic approaches to encourage engagement. Activities such as the Community Development Projects of the 1970s are laudable yet so often become bogged down in bureaucracy and a seeping away of energy. In order for the better future to arrive, the society must have a level of desire gained from envisaging that future. Maybe they didn’t have the long-term effect envisaged but Willats’ community-based projects provided a space for community imagination and excitement that a government-led plan can rarely achieve.

If there is a general lesson from Willats’ work though, it is that no specific future should be grafted onto a community–it should be up to them to choose the moment and direction in which they change their situation. So, on the ethical side, there must be a level of flexibility when working with a community–you cannot assume a one-size fits all theory or be unwilling to ask certain questions. While on the practical side, any activity must be undertaken with measured objectives and a long-term viewpoint. In summary, to engage with a community must be to make them the focus rather than the artwork; something that Willats aspires to but often falls short of.

With his practice riven by dichotomies in its methodology, both practical and ethical, and driven on by a vision itself split down the middle into opposing factions, maybe it’s not unexpected that it inspires such radically different feelings in viewers. The issues that define one half of this dichotomy are likely one of the reasons there are few candidates for direct artistic successors to it; another being that the requirements behind it of such a singular mentality make it a difficult act to follow. At the same time, it’s an affirmation of the size of his task that he has produced such an impressive practice that has been unable to be challenged by imitators. And when looked at more holistically what can be seen is that the concepts that Willats so radically brought to the fore have now become principles of today’s community art. His discursive method and his intended leaving of agency to the communities, showed a way for how art could integrate into the social groupings that it had previously left aside.

As a final thought on the value of Willats’ work today, neither Charles Fourier’s The Theory of the Four Movements or Tommaso Campanella’s City of the Sun are read these days for their reality but for the dreams they contain. As community work, Willats’ art fails in its aims. As art to be read like a book though, its dreams continue to inspire. As Marcuse wrote about art’s counter-consciousness: ‘the truth of art lies in its power to break the monopoly of established reality.’[61] This utopic other world that breaks open reality is what makes the heart of Willats’ art beat. Willats’ art does not describe a world, as in these books, where sea-monsters willingly pull ships or a second sun transforms the sea into lemonade. What it does present–and here a viewer is left to choose whether they want the utopia or the reality–is a dream of a world where a single artist can inspire a community and where an individual can create a future for themself in their own image, not that of society’s.

Oliver Noble is a researcher based in Marseille. He completed his BSc in Mathematics and Physics at the University of Warwick and his MA in Art History at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

Notes

[1] P. N. Sakulin, Iz istorii russkago idealizma: V. F. Odoesvskii (Moscow: Sabašnikovye, 1913), cited in Richard Stiles, Revolutionary Dreams (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 1.

[2] The author wishes to thank Scarlett Cannon for giving up her time to speak with the author as well as Sharon Irish, Grant Kester and Sarah Wilson, for their kind and patient criticism. The author is also very grateful to Philipp Ziegler and The Migros Museum, Zurich, for sharing their respective monographs on Willats.

[3] Judith Hart, cited in Alan Sked and Chris Cook, Post-War Britain: A Political History (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 1993), p. 191.

[4] Roy Ascott, ‘The Construction of Change’, Cambridge Opinion (January 1964), republished in Telematic Embrace, ed. Edward A. Shanken (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), p. 97

[5] Sharon Irish, Concerning Stephen Willats and the Social Function of Art: Experiments in Cybernetics (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), p.55.

[6] For a study of Willats’ kinetic art see Andrew Wilson, ‘Stephen Willats. Work 1962-69’, in Control. Stephen Willats. Work 1962–69 (London: Raven Row, 2014).

[7] Stephen Willats, ‘Configurations of Reality: Stephen Willats and Hannah Redler-Hawes’, in Human Rights (Middlesbrough: Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, 2017), p. 44.

[8] Stephen Willats, ‘Introduction’, in Stephen Willats (London: Chester Beatty Research Institute, 1964), n.p.; Roy Ascott, ‘The Construction of Change’, Cambridge Opinion (January 1964), republished in Telematic Embrace, ed. Edward A. Shanken (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), pp. 97 and 98; Roy Ascott, ‘Statement’, Control, no. 1 (1965), republished in Telematic Embrace, ed. Edward A. Shanken (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), p. 108.

[9] Willats, ‘Configurations of Reality: Stephen Willats and Hannah Redler-Hawes’, p. 40.

[10] As Beer later stated: ‘My message is that we must redesign that system, to produce freedom as an output.’ Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom (London: Wiley, 1974), p. 99. This point also permits comprehension of the title ‘control’ Willats chose for the magazine he founded in 1965.

[11] The homeostat was built by Ashby in 1948 to provide a mechanical example of environment adaption. Fig 4 in fact shows four homeostats connected together to form a self-stabilising system. However, the complete system has come to be called a homeostat––a terminology taken on by Willats.

[12] Stephen Willats, The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour (London: Gallery House Press, 1973), republished (London: Occasional Papers, 2011), p. 20.

[13] Stephen Willats, Speculative Modelling with Diagrams (Utrecht: Casco, 2007), republished in Art Society Feedback, eds. Philipp Ziegler and Anja Casser (Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2010), p. 517.

[14] Pask rarely makes explicit reference to Ashby’s homeostat in his work. However, the principles of the homeostat are evident in a paper such as Gordon Pask, ‘The Cybernetics of Evolutionary Process and of Self-Organising Systems’ [conference talk] (Namur: 3rd International Symposium on Cybernetics, 1961), published in 3rd International Symposium on Cybernetics (Namur: Association Internationale de Cybernétique, 1965).

[15] See Gordon Pask, ‘The Self Organising System of a Decision Making Group’ [conference talk] (Namur: 3rd International Symposium on Cybernetics, 1961), published in 3rd International Symposium on Cybernetics (Namur: Association Internationale de Cybernétique, 1965). A significant portion of Willats’ work was inspired by Pask. Firstly, the learning systems made by Pask that Willats looked after during his time working at the cybernetician’s company define the blueprint for Willats’ later computer works. Secondly, one of the earliest models Willats uses for his community works is taken from Pask. And thirdly, much of the terminology that Willats uses in his theoretical essays is seemingly carried over from Pask’s writings.

[16] Slogan, cited in David Stafford, ‘Anarchists in Britain Today’, p. 87; Stephen Willats, ‘Between a Symbolic World and a Contextual Reality: The Artwork as a Vehicle for Forwarding Counter-Consciousness’, Control, no. 10 (1977), p. 14; Jane Kelly, ‘Stephen Willats: Art, Ethnography and Social Change’, Variant, no. 4 (1997).

[17] Willats, ‘Configurations of Reality: Stephen Willats and Hannah Redler-Hawes’, p. 41.

[18] ‘Communism violates the sovereignty of the conscience, and equality: the first, by restricting spontaneity of mind and heart, and freedom of thought and action.’ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Qu’est-ce que la propriété? ou Recherche sur le principe du Droit et du Gouvernement (Paris: Brocard, 1840), republished What is Property? An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government, trans. Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1876), republished (New York: Dover Publications, 1970), p. 262.

[19] Stephen Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’, in The New Reality (Londonderry: The Orchard Gallery, 1982).

[20] Gordon Pask, ‘The Architectural Relevance of Cybernetics’, Architectural Design (September 1969), p. 494.

[21] One of Willats’ earliest uses of the term is in his artwork title Les problèmes de la nouvelle réalité (1977); see also Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’. Willats grew up in a United Kingdom that was experiencing significant changes. Huge Brutalist buildings were being erected, slums were being cleared and in the gaps between it all remained the bomb-sites from the second world war. At the same time, London had lost half a million inhabitants from its 1939 peak and films such as Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home (1966) displayed the plight of city-living.

[22] Charles Kiesler and Sara Kiesler, Conformity (Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1969); William C. Tabb and Larry Sawers (eds.), Marxism and the Metropolis: New Perspectives in Urban Political Economy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984). Marxism and Metropolis retrospectively contextualises Willats’ writings regarding the effect of an industrial-mechanical economic base.

[23] Willats, The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour, p. 36.

[24] For documentation of Man from the 21st Century see Willats, The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour, pp. 88-89.

[25] Willats, ‘Configurations of Reality: Stephen Willats and Hannah Redler-Hawes’, pp. 48 and 55

[26] For documentation of these two community works see Stephen Willats, Art and Social Function (London: Latimer, 1976). Willats had already been engaged in computer art for several years with works such as Visual Homeostat No.1 (1968-71) and Visual Meta Language Simulation (1971-72).

[27] Willats’ theory of the potentiality of questions is taken from his reading of Donald M. MacKay, ‘What Makes a Question’, in Information, Mechanism and Meaning (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1969). However, his use of questions seems to be founded in Ascott’s teaching methods.

[28] Willats was also fascinated by advertising theory. See Stephen Willats, Cognition and Advertising (1972), published in Art Society Feedback, eds. Philipp Ziegler and Anja Casser (Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2010).

[29] Irish, Concerning Stephen Willats and the Social Function of Art: Experiments in Cybernetics, p. 60.

[30] For examples of Willats’ use of the term ‘restricted codes’: Stephen Willats, ‘Introduction’, in Between Buildings and People (London: Academy Editions, 1996), pp. 11 and 21.

[31] See Basil Bernstein, Class, Codes and Control (London: Routledge, 1971) which collects his major writings of the 1960s. Willats often references Bernstein’s writings from this period in his essays. Bernstein is possibly the most important of Willats’ influences as his theories provide the link between the audience and the artwork in Willats’ work.

[32] Willats also uses the term ‘model’ in place of ‘code’ in his writings. The difference in use is ambiguous. Code is utilised in the context of language but, as Willats expands language to include objects, in a sense they represent two sides of the same coin.

[33] Stephen Willats, ‘The Externalisation of Models in Art Practice’, Control, no. 8 (1974), republished in Art Society Feedback, eds. Philipp Ziegler and Anja Casser (Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2010), pp. 329-330; Willats, The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour, p. 19. This process also owes a debt to Ascott who developed a conception of art as engaged in a mutualistic relationship with pedagogical tools. See Ascott, ‘The Construction of Change’.

[34] For documentation of Vertical Living see Stephen Willats, ‘The Counter Consciousness in Vertical Living’, Control, no. 11 (1979) and Stephen Willats, Vertical Living [tape recording] (Audio Arts, 1980). The following participant quotes are taken from these sources.

[35] Stephen Willats, Vision and Reality (Axminster: Uniformbooks, 2016), p. 25.

[36] See Stephen Willats, Vertical Living [tape recording] (Audio Arts, 1980). A collaborator in a later work has expressed the same, noting that although Willats would talk about the theory behind his work, this was more an interesting discussion rather than a pivotal part of the work to them. Author’s interview with Scarlett Cannon, 29 January 2021. By 2021 all the residents from the period had either passed away or moved out. Author’s interview with Anis Ahmed, Head of Skeffington Court Residents’ Association, 26 January 2021.

[37] Isaac Kramnick, ‘On Anarchism and the Real World: William Godwin and Radical England,’ American Political Science Review, vol. 66, no. 1 (March 1972), p. 11.

[38] Author’s interview, 3 February 2021.

[39] Willats, ‘The Counter Consciousness in Vertical Living’, p. 6.

[40] Sex Pistols, Anarchy in the U.K. (EMI, 1976).

[41] Willats, ‘The Counter Consciousness in Vertical Living’, p. 9.

[42] Stephen Willats, Contained Living [press release] (Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, 1978).

[43] Ascott, ‘Statement’, p. 108.

[44] For documentation of Pat Purdy and The Glue Sniffers Camp see Stephen Willats, Means of Escape (Rochdale: Rochdale Art Gallery, 1984), pp. 12-13.

[45] Mary Kelly has stated that Willats wanted to include the ‘riff raff’ in his works ‘meaning women, working class artists, and the Situationists.’ Juli Carson, Excavating Discursivity: Post-Partum Document in the Conceptualist, Feminist, and Psychoanalytic Fields, Ph.D. diss (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2000), cited in Louisa Lee, Discursive Sites: Text-Based Conceptual Art Practice in Britain, Ph.D. diss (York: University of York, 2018), p. 108.

[46] Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’, p. 14.

[47] Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’, p. 15; Herbert Marcuse, Counter-Revolution and Revolt (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972), p. 32.

[48] Stephen Willats, ‘Into the Night’, Aspects, no. 21 (1982), republished in Art Society Feedback, eds. Philipp Ziegler and Anja Casser (Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2010), p. 407.

[49] Ibid, p. 409. One suspects Willats might have met Graham though the American artist’s exhibition at the Whitechapel gallery which was the same year as Willats’. Willats had previously fallen out with some of the American artists: ‘I certainly fell out with artists — especially American ones — who thought that great art was universal. It was complete bullshit’. Stephen Willats, ‘King of Code’, Mute (2000), https://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/king-code, accessed on 3 February 2021.

[50] Author’s interview with Scarlett Cannon, 29 January 2021. As one example amongst others, Willats found ‘particularly pertinent’ Dale Lake, Perceiving and Behaving (New York: Teacher’s College Press, 1970) of which a large portion is focused on psychological experimentation methodology. Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’, p. 17.

[51] James Faure Walker, ‘The Claims of Social Art and Other Perplexities’, Artscribe, no. 12 (1978), p. 18.

[52] Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984 [epub] (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), chapter 2, paragraph 1.

[53] Stephen Willats, ‘Are you Good Enough for the Cha Cha Cha?’ [unpublished] (2002), published in Art Society Feedback, eds. Philipp Ziegler and Anja Casser (Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2010), p. 428. Cannon has described how Willats arrived looking like a ‘geography teacher’ on his first visit. Author’s interview with Scarlett Cannon, 29 January 2021.

[54] These quotes were taken from audio recordings made by Willats during visits to Hardy’s and Cannon’s flats. The Cha Cha Club members would also visit Willats’ studio where they would share a meal together. Author’s interview with Scarlett Cannon, 29 January 2021.

[55] Willats has stated that the design of a similar 1982 work that he made with Cannon was inspired by Russian constructivism. Willats, ‘Between Buildings and People’, p. 66.

[56] Alexander Herzen, cited in Richard Stiles, Revolutionary Dreams (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 18.

[57] Author’s interview with Scarlett Cannon, 29 January 2021.

[58] Stephen Willats, ‘The Cha Cha Club’, Flash Art (2017), https://flash—art.com/article/the-cha-cha-club/, accessed 3 February 2021.

[59] Willats, ‘The Emergence of a New Reality’, p. 11; Henry Berger, ‘The Renaissance Imagination: Second War and Green World’, Centennial Review, vol. 9 (1965), p. 46.

[60] Willats, ‘King of Code’.

[61] Herbert Marcuse, Die Permanenz der Kunst: Wider eine bestimmte Marxistische Aesthetik, (Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, 1977), republished The Aesthetic Dimension: Towards a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978), p. 9.