Austria on the Far-right Frontline

Oliver Ressler

In February 2000, Austria’s conservative ÖVP formed a coalition with the far-right FPÖ[1]. Back then, this was a taboo. Austria was the first European Union state to include a far-right party in its government. The EU imposed diplomatic sanctions on Austria. Inside Austria there were huge demonstrations against the government. There were also many inspiring initiatives within the arts scene: The Diagonale Festival of Austrian Film introduced a dedicated section for film formats opposing the government, Die Kunst der Stunde ist Widerstand (The Art of the Hour is Resistance). The magazine Camera Austria published an entire edition consisting solely of black pages, titled Austria 2000.[2] In Austria’s capital, Vienna, weekly demonstrations took place every Thursday. These Donnerstagsdemonstrationen began outside the Office of the Federal Chancellor and took a different—unannounced—path through the city each week, often venturing to the party headquarters of ÖVP and FPÖ, or disrupting events involving governmental ministers. At first, a few thousand people took part. They continued for months afterwards with crowds of a few hundred. The art initiative Public Netbase was among initiators of Volxtanz, a mobile DJ platform that moved across the city, bringing together DJ mixing, dancing and art activism. This format lasted several months, mobilizing and politicizing a younger generation. After February 2000, most art institutions decided to ban MPs from speaking at openings, refusing to allow art to become a platform of representation for politicians[3]. This left art institutions in a dilemma, given their financial dependence on public funding. When Kunsthalle Krems became the first art institution to back out, permitting then-state culture secretary Franz Morak to open an exhibition, the ÖVP politician was greeted with whistles by hundreds of artists and cultural producers, making it impossible for Morak to deliver his speech.

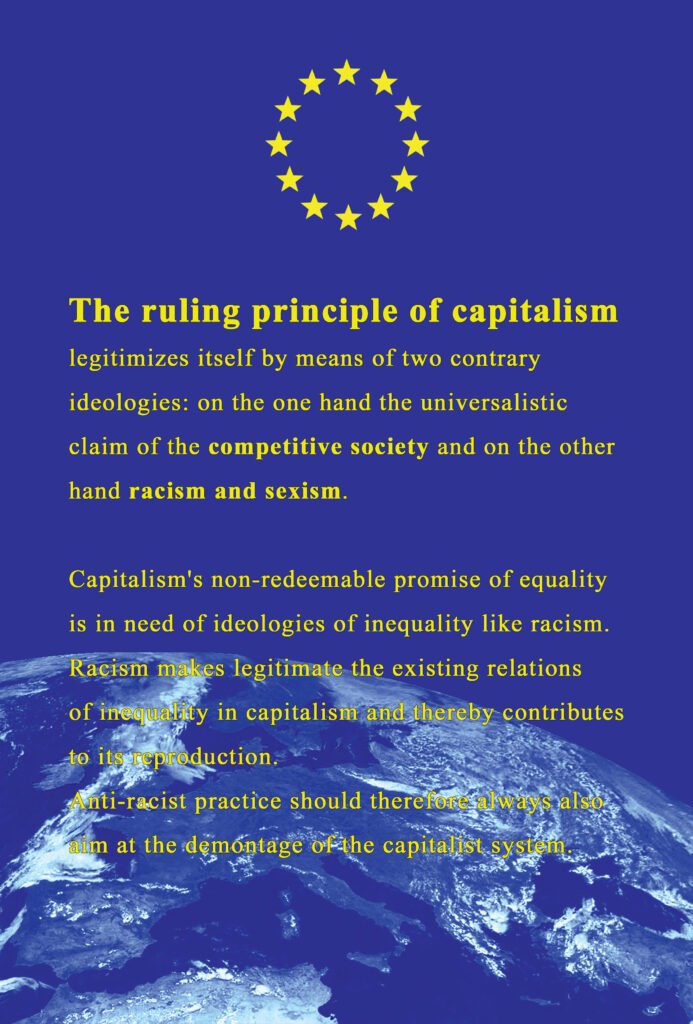

In its Danish version, the poster was presented in 90 city light boxes in Aarhus after an unsuccessful attempt to censor the project. (Courtesy of the artists.)

Resistance in the art world did not bring down the far-right government. But it worked to prevent the inclusion of fascists in the government from being normalized. It also helped establish networks among art workers, leading to fruitful collaborations and initiatives. It gave participants (including myself) a feeling of community in the rejection of this authoritarian project.

The coalition between ÖVP and FPÖ lasted from 2000-2007, followed by shorter resumptions in 2017-2019 and 2020-2021. On September 29, 2024, for the first time since the end of the Second World War, shockingly but not unexpectedly the extreme-right FPÖ won a national election in Austria. The conservative ÖVP became second, followed by the hapless social-democratic SPÖ. At time of writing, it is not clear which parties will form the government. After ÖVP, SPÖ and the (neo)liberal Neos have failed in building a coalition, the ÖVP will certainly build a coalition with FPÖ for the 4th time—now for the first time with an extreme-right FPÖ prime minister heading the government.

Whatever the outcome, in the past years, the political discourse has moved to the right dramatically. Even when the FPÖ wasn’t part of a government, far-right politics dominated. Examples of this shift could fill an entire book. I will just give one recent example: Only one day (!) after the news reported that Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad had fled to Russia, at a time when both Israel and Turkey recklessly seized the opportunity of the political vacuum to bomb hundreds of military targets in Syria, Austrian interior minister Gerhard Karner (ÖVP) publicly called for the repatriation of Syrian war refugees previously granted asylum. He proposed that the 40,000 refugees who have been in Austria for less than 5 years be the first to lose their asylum status due to the changed political situation in Syria.[4]

It is hard to imagine how even a minister from the FPÖ could have reacted more cynically, irresponsibly and disrespectfully, threatening people forced to flee a war zone. This indicates that far-right parties do not even need to be in government for their racist programs and dehumanizing discourses to be implemented.

The political situation is bleak. Meanwhile, across the EU, numerous governments now include fascists or the extreme right, as in Italy, Slovakia, Hungary, The Netherlands and Finland. Longstanding efforts to keep extremist forces out of government is over in Europe. Whoever forms the incoming Austrian government, will not face the sanctions or international pressure of the kind levied in 2000. This normalization of the far-right in a European context has also reduced the scope of oppositional tactics and art activism.

The poster is an invitation to an alternative diploma opening, a rally in front of the academy in Vienna against a FPÖ-led government on January 16, 2025.

(photo: O. Ressler.)

To date, public opposition has not succeeded in breaking up a far-right coalition in Austria. In all cases when far-right wing coalitions fell (2007, 2019 and 2021) it was due to internal corruption and scandals of the MPs, not external pressure.

I think this depressing situation can only be overcome through massive mobilization on the streets, including blockades and unlimited strikes. Neoliberal capitalism has proved to be a very successful redistribution machine—from the bottom to the top. The situation of working-class people won’t improve until it is understood by the majority that there is no solution in voting for the extreme right, but only in the struggle for a more democratic, egalitarian and just society that also makes decarbonization and climate justice central. Should these much-needed mass movements and uprisings emerge one day—something currently very hard to imagine in Austria—I am optimistic that plenty of opportunities will arise for artists and art workers to contribute meaningfully to the political struggle.

Artists will find possibilities to work on campaigns, to create movement designs, and to build tools for action and necessary infrastructure. Artists will help mobilize for actions, build movements, and try to connect with different potential partners to broaden activist coalitions. Artists undertook all of these tasks in the climate justice and Occupy movements, and elsewhere, participating in much larger numbers in proportion to their percentage of the population.

Oliver Ressler is an artist who produces installations, projects in public space, and films on economics, democracy, racism, climate breakdown, forms of resistance and social alternatives. Ressler had comprehensive solo exhibitions at Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb; Neuer Berliner Kunstverein; MNAC – National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest; SALT Galata, Istanbul; Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo, Seville; Museo Espacio, Aguascalientes, Mexico and Belvedere 21, Vienna. He has participated in more than 400 group exhibitions, including Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid; Centre Pompidou, Paris and the biennials in Taipei, Lyon, Gyumri, Venice, Athens, Quebec, Jeju, Kyiv, Gothenburg, Istanbul and at Documenta 14, Kassel, 2017. www.ressler.at

[1] FPÖ is an acronym for Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, which translates as Freedom Party of Austria, even though this far-right party has really nothing to do with freedom.

[2] https://camera-austria.at/en/zeitschrift/69-2000-2/

[3] Till today politicians opening exhibitions is a common phenomenon in Austria.

[4] Roughly 100,000 Syrian refugees were granted asylum in Austria since 2015, which has a population of 9.1 million inhabitants.