The Peril of Fetishizing Communication

Jae Hwan Lim

Introduction: South Korean Fetishization of Engaging Art

In South Korea, innumerable socially engaged art collectives, including Listen to the City, Mixrice, and Okin Collective, burgeoned their practices, exhibitions, and collections in art institutions from the early 2000s into the present day, which I discuss in-depth in this article. Such art collectives’ institutional presentations of social practice ephemera and installations that restage interactive moments outside the gallery space are aimed at sharing political messages for the audiences to become the artists’ bearers for future changes. These institutions’ approaches to bringing material objects from outside to inside their gallery spaces to share sociopolitical issues concomitantly raise a few questions, guided by three-pronged approaches. First is the exhibitions’ efficacy in disseminating political messages to the public beyond the cultural institutions. Second, based on artists’ experiences, there is a lack of criteria for determining if and how much the artists should be compensated for their socially engaged practice when their ephemera is presented in institutions. Third is relegating social practice’s value due to the ethical complexities of institutional association.

Based upon the three effects caused by cultural institutions’ material fetishization, I discuss the aftereffects/epiphenomena of museumization of sincere reciprocity within socially engaged art practices in South Korea. First, Listen to the City’s containment of its social meaning within institutions restricts connections with a broader public. Second, Mixrice’s conditional ask for monetary compensation for their works to be exhibited in institutions complicates the art collective’s sincere approach to marginalized communities. Third, Okin Collective’s adverse entanglement with institutions’ corruption could misguide the art collective’s intention to socially engage minorities in their practice. In analyzing these points, I majorly adopt anthropologist and political activist William Pietz’s notion of fetish and fetishism. This article also respectively incorporates social anthropologist Alfred Gell’s art and “agency,” feminist theorist Judith Butler’s “performativity,” and sociologist Bruno Latour’s “Actor-Network Theory” into the three collectives’ cases. Listen to the City’s art made through collaborative process act as a secondary agent, especially in a gallery space, compared to the art collective’s proactive agency as a mediator and message bearer; Mixrice’s restricted understanding of communication within the linguistics and philosophy of Avant-Garde art revealed its member’s abusive performativity; and Okin Collective’s project exhibited at a corrupt art institution entangled the collective with an unintended connotation caused by the work’s translation and networks. Above all, I contend that when they are displayed or owned by art spaces due to institutional fetishization, the presentation of socially engaged projects created through human relations causes restricted communication, compensated fetishism, and unscrupulous affiliation.

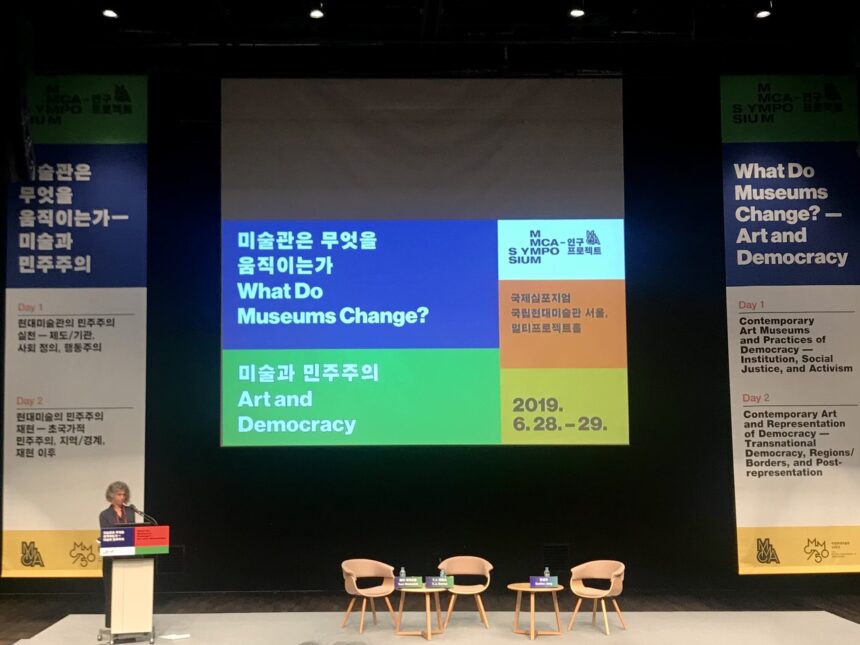

To build out these arguments, it is necessary to understand the Korean history of socially engaged art and its complexity when attempted to be presented at institutions. The 1980s minjung movement was majorly developed outside art institutions in democratization protest sites in Gwangju and Seoul, South Korea, catalyzed through artists’ collaborative banners, performances, and prints against militant dictator Chun Doo-hwan’s authoritarian violence against Korean citizens.[1] In the contemporary art scene, there are debates about whether Korean socially engaged artists should be referred to as post-minjung movement artists. Some still believe the movement continues because many participatory art collectives cooperate with social minorities, resembling artists’ collaborative efforts with struggling citizens in the 1980s for democracy.[2] However, it is contentious whether presenting institutional exhibitions of sociopolitical issues and reciprocal relations is part of the 1980s minjung artists’ aim and ideology. minjung art’s first large-scale retrospective at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea, in 1994 was considered a symbolic “funeral” for some artists due to its submissive manner as opposed to minjung movement’s anti-bureaucracy and anti-capitalistic value.[3] Meanwhile, the Western discourses on relational aesthetics, introduced by French curator and art critic Nicolas Bourriaud, increased Korean artists, art educators, and art institutions’ presentation of multifarious interactive and participatory art projects for decades, yet mostly within institutional environments.[4] As exemplified by Korean socially engaged artists’ institutional presentations and articles on Korean engaged art, numerous institutional artworks following Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics immanently “gave audiences access to power and the means to change the world.”[5] However, it is crucial to realize that such creation and consumption of aestheticized human relations defer sociopolitical changes to an “indefinite future or displace to a hypothetical viewer yet to be.”[6] As such entangled history of social engagement in art converges, the curation of the 2024 Gwangju Biennale in South Korea will be chiefly coordinated by Bourriaud with his ambitious intention to convey “humanity’s impact on the planet” through displays of art in gallery spaces under the Biennale’s provision.[7]

The Biennale’s decision to invite Bourriaud as the curator starkly exemplifies the Korean contemporary art world’s preference to aestheticize human relations through typified interactive and collaborative Avant-Garde art in institutional settings. Moreover, Gwangju Biennale’s celebration of its thirtieth anniversary in 2024 through Bourriaud’s lens seems to forge the exhibition’s detraction of Gwangju citizens’ bloodshed struggles outside institutions in the 1980s. The Gwangju citizens and artists fought against the dictatorial regime and capitalist corruption, which had nothing to do with material aestheticization and institution-based art practice. Such a contrast must be underlined because the Biennale insists it was “founded…in memory of spirits of civil uprising of the 1980 repression of the Gwangju Democratization Movement…”[8] As Bourriaud had argued that “any stance that is directly critical of society is futile,” his curation of the exhibition in Gwangju seems further contentious.[9] This paper critically examines the peril of contemporary South Korean art collectives’ fetishization of their dialogic practice and ephemera that became subordinated to cultural institutions; this upcoming Biennale hosted by the curator who has long advocated institutionalized human relations highlights Korea’s fetishistic cognizance on art and culture. The article scrutinizes collected works of art by Listen to the City in the Seoul Museum of Art, Mixrice in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, and Okin Collective in Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art owned by the Samsung Foundation of Culture. To further suggest that the complexity between human interaction and cultural fetishization through institutional spaces is not restricted to contemporary South Korea, I introduce another global phenomenon in Chicago, Illinois.

In 2022, Chicago Field Museum’s exhibition Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories received praiseful reviews by prominent institutions such as the Smithsonian, Northwestern University, and Chicago Tribune. Even Field Museum’s press release delineated its exhibition as a “groundbreaking exhibition” that “fundamentally change[d] the process of how we [the museum] co-curated exhibitions with communities” in representing the Indigenous culture in the museum’s gallery spaces.[10] Since Field Museum’s Indigenous exhibition initially opened to the public in the 1950s, they remained inaccurate depictions, displaying clothing backward, mixing up moccasin pairs, and putting artifacts upside-down.[11] What the museum proudly turned over through this exhibition is the process of co-creating the show with its Indigenous partners.[12] Field Museum was founded by Chicago businessmen and scientists who created the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, which notoriously portrayed various tribes as “the least civilized people of the world.”[13] [14] Such an anthropologic institution has historically yet erroneously represented cultural objects originally used and worn by native landers on American soil by forcing their presence inside gallery spaces. Field Museum’s institutional presentation of items used by Indigenous people is reminiscent of social practice artists’ institutional display of ephemeral materials from their engagement with social minorities. In both cases, institutions limit the correct use of their displayed items, complicate how the artist/cooperated community should be compensated, and increase the chance of disgracing artists’/institutions’ sincere collaboration with underrepresented groups due to the institution’s amoral history. Like Field Museum’s inclusion of the Indigenous community in its 2022 exhibition curation, the three Korean art collectives also engage with social minorities to create interactive art projects. Despite highlighting their interaction with marginalized communities through visual materials, they unavoidably confronted the peril of the fetish when their materials were exhibited at cultural institutions.

As investigated in these examples from Korea and America, Bourriaud’s curatorial aim to share “human impact” through works of art at Gwangju Biennale and Field Museum’s attempt to include the voices of the Indigenous community in the curation of exhibitions at its indoor galleries seem respectable. However, the inherent fetishism of the art institutional environment is an atemporal phenomenon that artists and historians of socially engaged art must be attentive to. It is because of art institutions’ history of material object idolatry through owning and presenting them in gallery spaces. The history of fetish is closely interjoined with the Christian theology that denounced the human body’s relation to idolatry. Pietz’s writing “The Problem of the Fetish” elicits early Carthage Christian author Tertullian’s perception of human misuse of material objects from the natural world, which was created by God, based upon God’s cosmology.[15] Natural objects such as gold, brass, silver, ivory, and wood could be neutral until humans abuse/fetishize them for violence like murder.[16] Pietz gives this source to highlight the long history of fetishism in early Christian society. As Pietz’s discourse on the problem of fetish and fetishism invariantly occurs in the contemporary international art and cultural fields, this article serves as a reminder of the corollary effects that fetishized socially engaged art embroils. This paper examines the three-pronged complexities of Korean contemporary social practice collectives, Listen to the City, Mixrice, and Okin Collective, for the Korean art field to introspect its continuing aestheticization and fetishization of human interaction within cultural institutions.

Listen to the City / Restricted Communication

Korean art collective Listen to the City (2009-Present) members have been ardently engaged and made works of art through community events and publications with the issues of environmental and social irresponsibility that destroy cultural diversity.[17] The collective has dealt with matters of disabled people, gender, and disaster; their recent projects involve the urban renovation and eviction forced by the Seoul Metropolitan Government over Cheonggye Stream and Euljiro region’s master artisans and artists, who have preserved the industrialization history and culture in Seoul, Korea.[18] Admittedly, Listen to the City may be one of the Korean social practice collectives “not focused on how our [the collective’s] activities are displayed or circulated in art galleries.”[19] Most of their collaborative practices tend to initially begin at the sites of marginalized communities’ struggle. Despite their fervor and concerted cooperation with social minorities, this section shares the limits of spreading social messages to the public outside institutions when such a socially engaged art collective’s works are fetishized as a collection and exhibited materials in art institutions like the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA).

“No One Left Behind” (2018) is Listen to the City’s project that Seoul Mediacity Biennale commissioned to create and SeMA owns as the institution’s collection. The piece is a video installation that shares disabled people’s experiences during the 2017 earthquake in Pohang, South Korea. Listen to the City’s message about natural disasters and the vulnerability that people with disabilities suffer, which was disseminated by presenting the collective’s works of art in the SeMA gallery space. Screening their interview video on the hanging surface, conducting workshops, and displaying manual publications on the wall and a table surrounded by five chairs, SeMA objectified Listen to the City’s collaborative efforts as its art collection.[20] The project began with the collective’s workshop with the NoDeul School for the Disabled based in Seoul, Korea in July 2018 and a subsequent workshop at SeMA in October 2018. These gatherings invited participants to create scenarios and drawings that delineate resilience methods that can save social minorities in the case of natural disasters. However, the groups of participants varied depending on the institution’s characteristics. The former gathering was at the school for disabled people. Listen to the City members and the school’s associate co-led the program.[21] The workshop at the school shared the experiences of the people with disabilities who faced the Pohang earthquake, introduced existing manuals for disabled people’s preparation for natural calamities, researched foreign manuals, and drew maps of the school and the region where the school is located to discuss earthquake scenarios.[22] While the workshop at SeMA consisted of sessions similar to the former, it invited any fifteen participants who “take advantage of SeMA” at no charge.[23] By bringing people’s attention to social minorities’ risk and vulnerability to natural disasters in the workshop invitations, both gatherings revivify the issues that underrepresented communities in Korea have long struggled with yet are rarely discerned by the public.

It is uncontentious whether Listen to the City’s workshops in the two institutions were impactful even if they affected different groups of people. Nonetheless, the art collective’s presentation of its cooperative art in cultural institutions such as SeMA inexorably impedes changes to the omnipresent issues that disabled people face in their quotidian occasions, such as natural disasters. Gell’s definition of agency describes art objects as mere indexes of its maker’s agency.[24] Because art objects are insufficient as self-agents, Gell suggests they function more as secondary agents that “become enmeshed in a texture of social relationships.”[25] Listen to the City’s manual publications documenting the voices of the disabled communities, and the table set up for the workshop at SeMA gallery is reminiscent of Gell’s suggested notion of secondary agency of materialized art objects. The static materials presented as forms of art at the art institution subordinately own “state of the physical universe” because the art collective created and owned the primary agency of the materials after directly interacting with people; the materials do not initiate causal sequences caused by “acts of mind or will or intention.”[26] Thus, Listen to the City’s gatherings proactively disseminate agencies to workshop participants and spread their goal to solve the issues that disabled people struggle. On the other hand, the related materials on display have limited agency to spread such messages by themselves. While the exhibition shares the minorities’ adversities to the museum visitors through the museum’s fetishized materials, it is questionable how many of these audiences can efficaciously make changes to the recalcitrant matters that the disabled community deplores just by encountering such materials owning secondary agencies.

The workshops share ostensible similarities as they intended to deploy inclusive meetings with communities to rekindle the issues about minorities’ struggle under natural calamities. However, there are starkly different ranges of impact that these two workshops could spur due to the locations the institutional spaces insinuate with different possibilities of the art collective’s fetishization of its interaction with people at the workshops. Discussing the history of Christianity’s concern with vain observances, Pietz shares how the superstitious practices of “religious self-deception” involved material objects.[27] Here, religious self-deception is defined as vain observances through material objects that people construe to resemble God yet are understood as illegitimate sacramental objects by Christianity. While the objects used during magical invocations that became someone’s fetish were distinct from immaterial acts of the soul that are “proper to the true faith,” only churches could become vehicles of the objects for their faith and divine power.[28] As Pietz suggests about fetishized objects’ bewitching aura in a religious institution, Listen to the City’s copious reinvigoration of the concurrent issues through physical workshops and materialized publications become objects that inhere different meanings, and reach disparate groups of communities in separate institutions. The former workshop at the school for disabled people formed a space where people with disabilities could voice their concerns and hardships about disastrous scenarios from first-person experiences. The former interaction with disabled people has more potential to expand reciprocal discussions. The space was not targeting idolatry of material objects like museums, which allowed the possibility of inviting lawmakers and local bureaucrats to join the conversation with the disabled participants to appeal for actual changes to the current law that scarcely protects disabled people. On the other hand, the latter gathering at the art museum restricts the reciprocity between a wider group of people because it is happening within the art institution and targets the museum’s cultural consumers. The art collective’s interactive moments and ephemeral materials created through reciprocity become fetishized in the art gallery space when the art collective brings them into the institution. Thus, there is a limited chance for the artist to discuss their message with a broader public beyond the audiences who visit art galleries.

Regardless of such risk of institutional fetishization and restriction, Listen to the City brought the issue of the disabled communities’ struggle into SeMA. The art collective provided a prompt to the museum workshop participants to suppose a six-point-eight magnitude earthquake occurred in Seoul and what would happen to them during the workshop at SeMA.[29] Through various styles of drawings and texts, the workshop participants imaginatively drew their narratives of devastating scenarios during the natural disaster.[30] The art collective compiled the participants’ stories into a short publication. The visuals of the workshop contents were also displayed on the wall of SeMA’s gallery for the Seoul Mediacity Biennale. Listen to the City presented the institution’s fetishized materials for the Biennale exhibition, which alludes to Pietz’s example of malignant fetish objects. The fetish was considered enmeshed in ascetic sorcery by Christians. Hence the Church hypnotized the objects by manufacturing them with the religious institution’s sacred and “divine power.”[31] By presenting the voices of the disabled people at the museum’s white cube space through Listen to the City’s documented publications and the documentary video, the collective’s works of art show the museum’s sacralizing power, like the Church. They also forge the institution’s sociopolitical position as a communion among social minorities and socially engaged artists. As if the museum has a peculiar divinity, Seoul Mediacity Biennale’s commission and SeMA’s collection of the “No One Left Behind” enchains the records of the disabled people’s empirical hardships inside the museum space. Such a fetishized ownership allows the art gallery audiences to encounter the underrepresented communities’ hardships through art and duly, not urgently, make changes in the future for the marginalized community. Even if the materials exhibited at SeMA have the potential to impact audiences, due to the museum’s fetishistic enchainment of the works within the institution and their lack of agencies, the materials themselves cannot reach a wider group of the public beyond the institution. Therefore, Listen to the City’s fetishized materials at SeMA cannot make urgent changes for the social minorities within the gallery space. The materialized video, workshop ephemera, and manual publications need to await for the art collective to activate them outside the institution to make more practical changes with people in charge of legal matters.

SeMA’s exhibition of “No One Left Behind” in 2018 hosted one workshop at the institution for a few hours and presented the video, publication, and table set up at the gallery for other days of the exhibition. For the Seoul Mediacity Biennale in 2018, there were neither subsequent gatherings with disabled communities at SeMA nor additional workshops with lawmakers or experts that could further educate the gallery visitors about the minorities’ hardships and resilience to solve their plights.[32] The marginalized communities’ voices were repeated in the looped video or hung on the wall for the viewers to unilaterally acknowledge Listen to the City’s collaborative procedure with disabled people. Listen to the City’s workshop at the school for the disabled community and at SeMA entail different types of agencies to impact the public. For instance, Listen to the City’s typified presentation and social engagement at SeMA was fetishized in an art institution, which contrasts with public collective gatherings in Peru. In 2000, innumerable Peruvian protestors stood throughout public sidewalks and squares to express their political struggles outside art institutions. Peruvian citizens washed the red and white national flag out in the streets, playing a crucial prefigurative role in ousting Peru’s corrupt President Alberto Fujimori.[33] The protestors used the public spaces to make collective gestures to remove their unscrupulous president. They washed the flag every week since the election, calling for the President to step down and conveying their gesture of cleaning their corrupt national leader through recurring actions against the bureaucratic power. Peruvian citizens who sincerely wished to oust their national leader cooperated with the flag-washing while disseminating their proactive agencies. The participating public effectively shared their political message with wider citizens through acute gatherings and actions, which prevented art institutions’ fetishization of their movement or ephemera.

One may exalt that Listen to the City’s institutional presentation of its works indoor can still bring public attention to the issues that social minorities consistently face in natural disasters. Nevertheless, SeMA’s fetishization of the collective’s communicative art, made through human relations, restricts the issue within the discourse of art in the context of the art institution. SeMA’s hermetic fetishism in its institution, where artworks are presented and discussed among gallerygoers, prevents the artwork from owning an agency to proactively communicate with a broader public about underrepresented communities’ struggle with natural calamities. The sociopolitical proclamation implied in Listen to the City’s institutional display subordinate manual publications and video as SeMA’s institutional fetish materials. Thus, Pietz’s claim that “anyone can manufacture an object intended for worship, but only the priestly lineage of the church can empower them for the…faithful” is reminiscent of the case of “No One Left Behind” at SeMA[34] SeMA’s physical presence as an art institution turns functional objects into something venerated by museum visitors because of the bewitching aura the space entails. Listen to the City’s conflated effort to include and visually present underrepresented recounts about disabled people in a catastrophe is meaningful and crucial. However, when the collaborated physical materials are displayed at such a cultural institution constituted through bureaucratic systems, they will face limited power to disseminate messages to a broader audience outside the gallery space.

Introducing Listen to the City’s mission, it describes that the collective “endorses…publicizing the issue of the privatization of the commons…and…giving voice to the voiceless.”[35] When a cultural producer attempts to share the voices of the voiceless through art but an institution privatizes the work and restricts its power in impacting a broader public, such an unabated issue continues to limit social changes for the marginalized. Listen to the City continued its sequential workshops about the same issue with the NoDeul School for the Disabled and the Yonsei University’s Disability Rights Committee in November 2019.[36] I contend that these gatherings outside art institutions are more effective in reciprocally deliberating diverse opinions and ideas beyond obsolete cultural institutions. The first section of this article instantiates a Korean art museum’s fetishization of the Korean art collective Listen to the City’s collaborative project and the constraint of message distribution caused by their materials’ secondary agency and the art institution’s fetishization of their materialized artworks. The second portion of the paper discusses the complexities of compensation and an artist’s performativity when social practice art becomes an institution’s fetishized material object.

Mixrice / Compensated Fetishism

Another South Korean contemporary art collective known to support social minorities is Mixrice (2002-Present, currently more active as ikkibawikrrr). Its members fortified relations with Southeast Asian migrant workers in South Korea through concerts and videos to reflect the community’s hardships before the collective restructured itself in 2019; I discuss the cause of the reconstitution in-depth in this section of the article.[37] The art collective has been untrammeled to present and sell its ephemera to cultural institutions from social practice environments where the collective members genuinely formed connections with their collaborating communities. Mixrice’s participation in exhibitions and biennales, as well as sales of their works of art, involved international art institutions such as the Seoul Museum of Art, Korea; Nam June Paik Art Center, Korea; Taman Ismail Marzuki, Indonesia; Pori Art Museum, Finland; Sharjah Biennale, United Arab Emirates.[38] Among these global institutions, Mixrice has many associations with the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) in its art career. Mixrice was chosen as the MMCA Korea Artist Prize 2016 winner, exhibited and sold their art to the museum, and had conflicts with the museum about the pay for exhibiting their works in 2019.

Mixrice has two of their works collected in the MMCA. “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’” (2009) is a paradigmatic fetish owned by the museum. Institutional exhibition and collection of an art project through communicative situations cause the complexity of compensating artists. “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’” is a recast of a play stage in which Bangladesh migrant workers in Maseok-ri, South Korea, performed a reenactment of unfair working situations.[39] While the migrant workers wrote, directed, and acted their drama “The Illegal Lives” (2010), Mixrice documented the performances in the form of videos, photos, and writing to “give them [the migrant workers] a voice and attempts to ease their sense of isolation.”[40] “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’” consists of a single-channel video on a monitor and some ephemeral materials such as the play script and tools that resonate with the narrative of the drama. Through the piece, Mixrice intends to show what it means to live a life with an illegal migrant status in South Korea, especially working under malicious factory owners.[41] It was elusive to find MMCA’s purchase price of Mixrice’s “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage.’” However, Yang Chul-mo, one of Mixrice’s duo members, raises the question of how much artists should be monetarily compensated for allowing art institutions’ fetishization of artists’ works through exhibitions.

In 2019, MMCA invited Mixrice to present “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’” at the institution’s fiftieth-anniversary exhibition, The Square: Art and Society 1900-2019, which included about two hundred modern and contemporary Korean artists’ works in the museum spaces.[42] For exhibiting the installation piece for five months, Mixrice was offered a total of 41,250 Korean Won (approximately thirty-one US Dollars) based on the museum’s peculiar calculation that added around 250 Won (about nineteen US Cents) per day; the calculation method was referenced to the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism’s “Art Creation Standard Fee” policy.[43] The policy insists on multiplying exhibition days (around 150 days) by 50,000 Won (the policy’s suggested average pay for the exhibiting artists per day) and dividing it by the number of participating artists (about 200).[44] However, such a calculation rather decreased Mixrice’s compensation to 41,250 Korean Won, which was even lower than the policy’s proposed average pay of 50,000 Won.[45] Thus, Yang refused Mixrice’s participation in the exhibition. Yang’s reasoning about artists’ compensation for exhibiting his collective’s art at institutions sounds rightful, as artists are allowing the institution to fetishize their work. In a broader context, this discussion relates to South Korea’s lack of welfare and financial support for artists and cultural producers, which often lead to artists’ deaths due to the hardships of making a living.[46] Meanwhile, such a rebuttal expands to a bigger question for socially engaged artists who work with communities: How much should the communities participating in social practice projects be compensated whenever the organizing artists’ collaborated art is presented at art institutions?

Yang’s interview with the Korean Broadcast System in October 2019 about the compensation mentions Mixrice’s refusal to present its work at the MMCA’s fiftieth-anniversary exhibition.[47] However, many Korean independent blog reviews of the exhibition include the images of the collective’s “A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’,” which obscures whether the collective rejected the exhibition participation or participated with any compensation.[48] In Mixrice’s installation piece at the MMCA’s exhibition in 2019, the Bangladesh migrant workers continuously performed in the video screened through the installed monitor to share the grim reality of the migrant workers in South Korea. The installation consists of the video on the monitor and symbolic objects that connote migrant workers, such as a combination plier and work gloves. These materials emulate Mixrice’s communicative moments with the migrant workers who acted for the collective to record the video. Notwithstanding the piece’s dissemination of sociopolitical messages to the public, such a corporealized installation of human relations is fetishized in the art museum through an exhibition. This cause and effect raises the question of whether Mixrice’s collaborative video installation should be monetized or if it should be presented to the public with no compensation. The complex question of Mixrice’s financial compensation for their institutional presentation of art can be illuminated with Pietz’s case study of the Dutch West Indies Company. Pietz’s example of the seventeenth-century Dutch West Indies Company suggests its global influence of European mercantilism.[49] Pietz contends the ideological function of the powers and operation of the material world that arises “within new commercial consciousness fostered by novel forms of economic organization.”[50] The company’s introduction of European capitalist value through its material goods resonates with MMCA disseminating fetishistic value through its art collections. Therefore, it is presumable that MMCA’s role as an art collecting institution instigated Yang to discuss the financial value of Mixrice’s art installation made from collaborative processes; MMCA runs an internal institution called the “Art Bank” since 2005, which purchases artworks to “stimulate the art market…by acquiring, leasing, and exhibiting works by Korean artists.”[51] This conversation may not have happened had the work not been exhibited in an institution with financial dimensions.

Yang’s impassioned claim about getting compensated for exhibiting Mixrice’s work at MMCA could serve individual artists and socially engaged collectives, who must spend money to conduct gatherings with social minorities and create material objects that allude to their reciprocal communication with the marginalized. However, Yang’s rightful request for compensation complicates Mixrice’s sincerity towards the art collective’s collaborators. The institutional fetishization of the art collective’s work about their relationship with the underrepresented community is reminiscent of the abusive disposition of the participatory performance by artist Santiago Sierra. Sierra’s “160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People El Gallo Arte Contemporáneo, Salamanca, Spain. December 2000” (2000) is a video documentation that hired four sex workers addicted to heroin for the price of a shot of the drug to give their consent to be tattooed on their backs.[52] By displaying the staggering video that points to the consequential social issue of heroin addiction, Sierra intends to divert the audience’s attention outside the cultural field. Nonetheless, Sierra’s compulsory affordance that he abuses instantiates how the artist gains fame and monetary compensation from art institutions and cultural fields. By wielding his power over a group of social minorities and presenting the dreadful video that portrays the marginalized as inferior, Sierra connotes that it is okay to treat people with drug addiction contemptuously, not as equal humans.

Likewise, Mixrice shares migrant workers’ struggles with the Korean factory owners’ mischievous behavior by playing their video at MMCA. The abstruse criteria on monetary compensation for artists and participating performers become even more complicated when the art is presented in institutions as their fetish. Along with how much the artist should be compensated for exhibiting their works at an art institution, whether the performing minorities are compensated as equal or more than the artist is another complexity that ensues for the socially engaged collective to consider. Mixrice and Sierra’s objectification of their human subjects can still be contentious even if their video documentations were not exhibited at art galleries; the former documented the migrant workers’ performances, and the latter directed the four women’s tattoos on their backs. Most of all, such artists’ works that objectify humans and their reciprocal relations become various institutions’ fetish materials in art galleries. This complication should be grappled with by socially engaged artists who are tempted to present their collaborative art at art institutions and art institutions that function as the fountainheads of object fetishization through art collection and exhibition. It is because artists and art institutions conjoin the fetishization of human relations, which quintessentially marginalize collaborating communities. Artworks exhibited at galleries inside art institutions hypnotize that the artists’ artworks function as the bearers for solving social issues outside the art institutions. However, there are more cognitive impacts on the audiences than making them join the artists’ performativity for social changes.

Butler’s notion of gender performativity relates to Mixrice’s and Sierra’s restricted definition of art within the conventional art field. Like how actors are prepared to perform a play that requires both text and interpretation, “gendered body acts its part in a culturally restricted corporeal space and enacts interpretations within the confines of already existing directives.”[53] Similarly, Mixrice and Sierra shocked people through art in order to share reality outside gallery spaces; they performed the forms and presentations of epitomized Avant-Garde art within the locus and discourse of art institutions where fetishizations occur. Due to these artists’ restricting performativity within the art field, their approaches to humans denote impersonal characteristics that lack morality and sincerity. Along with their restricted performativity as artists, fetishism of art institutions further degenerates artists’ ethics. One of “the truths of the fetish” that Pietz suggests is the “material fetish as an object established in an intense relation to and with power over the desires, actions…of individuals whose personhood is conceived as inseparable from their bodies.”[54] The question Mixrice member Yang raised about getting monetary compensation for fetishizing the collective’s video installation of social minorities at art spaces concomitantly induced his immoral scandal regarding his sexual harassment of female co-workers. Yang admitted his harassment when he served as the director position at a government-funded project hired by the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture in August 2019, which was two months prior to his public argument about Mixrice’s compensation from MMCA.[55] Thus, I contend his sexual fetishism and commodity fetishism coincided with his performativity as an artist who wish to covey his power in the art field through institutional affiliations.

While serving his hierarchal location as a cultural project director, Yang made inappropriate remarks to his female co-workers. They include words such as, “I want to have sex with you” and “(People) would have wanted to seduce you as you look like a rustic and pure North Korean woman,” which reveals the artist’s sexual fetish.[56] These violent and fetishistic remarks resonate with Yang’s complex arguments about how much and whether artists should be paid for allowing art institutions’ fetishization of his collaborative art installation. It is because Yang expressed his sexual fetishism over female co-workers when directing a cultural project, which was going to become the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture’s cultural fetish. These tragic causes and effects relate to Yang’s limited performativity within the art field, which prioritizes art’s fetishization over human relations. Thus, his sexually fetishistic remarks hurt co-workers and remarks on compensation hurt marginalized collaborated communities.

Yang considered it okay to express his sexual and commodity fetishism towards social minorities with his impactful performativity as a named artist in the Korean art field. Yang’s fetishistic comments allude to both minorities as inferior beings, inflecting his lascivious thoughts towards the female co-workers and lack of respect for the migrant workers he collaborated. Thus, Yang’s aim to fetishize Mixrice’s work in art institutions as commercial objects and to fetishize his co-workers through his artistic performativity causes the question of whether the migrant workers whom Mixrice cooperated with were rightfully compensated and treated with no fetishistic encroachment. Beyond articles on compensation and Yang’s sexual harassment, Mixrice’s mistreatment of the workers is obscure in public documents. However, the complex questions he raised through these incidents function as lessons for people in the art field. As Yang’s cases reveal, the peril of institutional and sexual fetishism jeopardized Mixrice’s relations with social minorities, leading to Yang’s decision to quit his art career.[57] While the second portion of this article discusses the causality of compensated fetishism, the last section of the paper tackles the possibility of the pejorative value of artists’ social engagement when the institution art collective exhibits is associated with corruption and amorality.

Okin Collective / Corrupt Affiliation

Like Listen to the City and Mixrice, Okin Collective (2009-?) was one of South Korea’s most prominent art collectives in South Korea for advocating for social minorities. The collective cared for residents and the space about to be evicted and demolished at the Okin Apartment complex in Jongno District until indistinct issues arose within the collective in 2019; thus, it is unclear whether the collective ended in 2019.[58] Creating exhibitions, performances, installations, and communal activities with the apartment residents, Okin Collective poised as a community organizer and expanded their solidarity with other social minorities, such as wrongfully laid off workers.[59] One of Okin Collective’s institutional presentations of their project was at Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, run by the Samsung Foundation of Culture in 2016. As part of the museum’s biennial exhibition, ARTSPECTRUM, Okin Collective was invited to present their interactive installation “Art Spectral” (2016) at the institution. The piece was composed of a giant wooden floor, small bags of rice, a microwave, compiled readings, sound, and a video.[60] It allowed audiences to read the materials on the wooden floor while engaging with the microwaved rice bags, following exercise actions in the video, and listening to the ambient sound playing from the embedded speaker in the floor structure. Through the installation and the piece’s title includes the term “spectral,” Okin Collective refers to the unstable social status of the emerging artists, most of whom “disappear” outside exhibition spaces like ghosts to work and support their lives.[61]

Even if Okin Collective shares the message about contemporary artists’ deprived reality outside the institution through the piece, the collective’s decision to participate in an exhibition at Samsung’s art institution strengthens the artwork’s tie with Samsung’s corrupt history. One can interpret that Okin Collective’s presentation of the installation at Leeum intentionally critiqued Samsung’s neo-liberal impacts on South Korean societies as Samsung is the country’s biggest and richest conglomerate. Nevertheless, the collective’s project is entangled with Samsung through the repetitive network translated, as Latour defines, between the piece and the institutional locus in which it was installed, which causes the artists’ unintended affiliation with the corporation’s amorality.[62] To describe further Samsung’s corruption and its impact on social minorities, it is crucial to underline the company’s bribery scandal in 2007. Through the whistleblowing of the former chief attorney of Samsung, Kim Yong-chul, Samsung chairman’s wife, Hong Ra-hee, who was the director of Leeum then, was alleged of purchasing Roy Lichtenstein’s painting “Happy Tears” (1964) with Samsung’s slush fund.[63] The whistle-blow is not only related to Samsung’s money laundering but also its focus on the capitalist fetishization of art while disregarding social minorities who were injured working for Samsung.

When Hong was accused of an illicit art purchase in 2007, Hwang Sang-gi, the father of a 23-year-old daughter who died of leukemia after working at a Samsung factory, struggled to receive an apology from Samsung for his daughter’s death.[64] While it took eleven years for Hwang to get Samsung’s apology for its mismanagement of factory and workers, there were also other victims who experienced sterility diseases, Rheumatoid Arthritis, thyroid cancer, and different occupational illnesses from working at Samsung’s semiconductor factory.[65] Samsung contradicts its unscrupulous capitalization of culture through its art collection and inhumane treatment of workers. Thus, it reads ironically that Okin Collective will present its artwork, “Art Spectral,” in Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art’s gallery space, and share messages about artists’ deprived lives at the art institution. “Art Spectral,” as the mediator between Leeum and its audiences, inadvertently links Samsung’s financial support for the cultural exhibition to the struggles of artists. However, in the installation’s translation of its meaning to audiences, the piece “distorts the content of the elements they mediate according to their own [interrelation of] operations.”[66] Latour’s Actor-Network Theory discusses mediation and translation between people and things.[67] He states that people and things are intertwined due to “heterogeneous association through translation,” which resonates with Okin Collective’s presentation of its artistic materials at Leeum, which has a corrupt and inhumane history.[68] It is salient to apply Latour’s theory in analyzing Okin Collective’s conflicting goal to advocate for social minorities by exhibiting its art at Leeum and Leeum’s affiliation with Samsung’s fetishistic amorality.

In their interview, Okin Collective indicated that the collective’s goal is “to express social issues through the language of art,” but “not in the method that uses direct criticism,” which resonates with Bourriaud’s comment that “any stance that is directly critical of society is futile.”[69] The artists’ remarks hint at their art’s material value within institutional systems that allow audiences’ personification under Leeum’s support for the exhibition. Okin Collective pertains to be one of the significant art collectives that advocate underrepresented communities in the actual sites of the struggles. Thus, it is contradictory to recognize Okin Collective’s cultural affiliation with Samsung and their aim to share the struggles of social minorities through exhibiting their installation at a morally controversial institution. Hong resigned from the Leeum director position in 2017, one year after “Art Spectral” was exhibited, because her son, Samsung Electronics Vice Chairman Lee Jae-yong, was taking the corporation’s lead.[70]

While Hong and Leeum deny the purchase and ownership of “Happy Tears” until now, Hong’s resignation in 2017 and Samsung’s apology for the workers’ death and disease in 2018 formed a smooth transition for Lee’s promotion to the Executive Chairman of Samsung Electronics. Lee is evaluated to not have any professional training or possible interest in collecting contemporary art, but Samsung’s cultural institutions, including Leeum, prosper its cultural capital through art collections and exhibitions.[71] On top of the translation that “Art Spectral” reveals in relation to Samsung’s corrupt art institution, Pietz’s point on the constitution of personal relations through material entities also resonates with Okin Collective’s presentation of art through Leeum’s material fetishization.[72] According to Pietz’s definition of fetish, the order of material entities, such as the market, constitutes the order of personal relations to social production and culture. In other words, the market constitutes what should be the public’s fetish by defining social values, “thereby establishing a determinate consciousness of the ‘natural value’” in society.[73] Samsung’s fetishistic collection and exhibition of international artworks through cultural spaces like Leeum prioritizes its sociocultural stance as an influential institution with plutocratic power; Leeum’s recent Maurizio Cattelan solo exhibition drew thousands of audiences to its gallery.[74] However, the cultural capital they own is constructed by devaluing the lives of Samsung’s workers. As Samsung handles numerous businesses in various fields, including electronics, apartments, insurance, medical, biology, heavy industries, engineering, hotels, and fashion, South Korea (Republic of Korea) is often referred to as the “Republic of Samsung.”[75] The term hints at Samsung’s cultural and economic impact on South Korean society. Samsung’s fetishistic art collections and Okin Collective’s fetishized presentation of its installation at Leeum cloak Samsung workers’ afflictions and degenerated human rights caused by the conglomerate’s prioritization of art fetishization over human lives.

Okin Collective’s dematerialized installation at Leeum’s ARTSPECTRUM evaded obsolete object-based art and experimented with the audience’s participation, which one could insist that the collective prevented the commodification of its art. Nonetheless, its presentation at the institution is translated to the audience as to whether it was appropriate for the collective to display its piece about the artists’ struggle at Leeum, run by the conglomerate that capitalizes on humanity. Samsung’s cultural capital that was possible by profiting off of labor abuse resembles numerous Western art institutions’ association with the Sackler Family that was untrammeled to provide donations to art museums and galleries by selling OxyContin, a highly addictive opioid-based pain medication, to patients.[76] Since 2018, photographer Nan Goldin has led guerrilla protests with her group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) at world widely known museums that were receiving philanthropic support for their galleries, curator and internship positions and new wings; the institutions include but not limited to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, the Louvre Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Tate, the Harvard University’s Art Museums, and the Smithsonian.[77] By occupying the galleries at Guggenheim, throwing pill bottles into the pools at the Metropolitan’s Sackler Wing, and laying down on the Harvard Art Museums’ entrance space, Goldin and the P.A.I.N. members chanted the institutions’ removal of the Sackler Family’s names from their walls and the pause of receiving funds from the family. The movement was effective as museums like the Metropolitan, Guggenheim, and Tate stopped taking donations from the Sackler Family, cutting their relationship with the amoral corporation.[78]

Goldin’s bold decision to lead the anti-drug action stems from her intimate photographs that document drug use, violence, and deaths from AIDS, which are displayed and owned in numerous museums, including the Metropolitan. Her protest against cutting the abovementioned institutions’ ties with a pharmaceutical company that abuses drug use starkly contrasts with Okin Collective’s artistic engagement through “Art Spectral” at Leeum, which did not proactively pinpoint Samsung’s violence over humans. While Goldin’s strident criticisms of art institutions instantiate the artist’s sincere act to make actual changes within and outside the art institutions, it also epitomizes the risk the artist had to take for any chance of the institutions’ removing her artworks from their fetishized collections. In contrast, Okin Collective did not resist presenting their participatory project about the social tragedy at Leeum nor critique Samsung for exacerbating human rights. The collective’s artistic activity through Leeum’s biennial comes to be, as Pietz defines fetishized materials, “directed by the impersonal logic of abstract relations…guided by the institutionalized systems” for the museum’s fetish.[79] Thus, I contend Okin Collective’s participation of Leeum’s biennial inevitably forged Samsung’s cultural fetishization and capital over humanity.

Conclusion: Sincere Reciprocity Beyond Aestheticization

This article began with Nicolas Bourriaud’s assignment to curate the upcoming fifteenth Gwangju Biennale in 2024 to celebrate its thirtieth anniversary. As the leading figure in relational aesthetics since the 1990s, Bourriaud’s idea to bring political issues and interactivity into art gallery spaces influenced many Korean artists who handled sociopolitical issues. As exemplified through institutionally fetishized art by the three representative contemporary Korean art collectives, Listen to the City, Mixrice, and Okin Collective, the aftereffects of art institutions’ material capitalization cause unintended consequences to the Korean sociocultural fields. These museums and artists followed Bourriaud’s notion to aestheticize human relations within the institutions. First, Listen to the City presented their workshop and related ephemera about disabled communities’ struggle during natural disasters at the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) in 2018. The display of the object materials, such as manual publications and video, allowed Seoul Mediacity Biennale and SeMA to objectify/fetishize the project by funding it and allowing their exhibition at the museum’s gallery space. The displayed items themselves lacked, as Alfred Gell would define, the agency to share inherent messages the artists intend to disseminate. They are comparable to the members of the collective imbued with primary agency, who led human-to-human gatherings at SeMA and the school for disabled people. Listen to the City’s publications installed on SeMA’s wall and table functioned as secondary agents that insufficiently enmeshed the collective’s social relations with people with disabilities. In contrast, the collective’s presence during the workshops extended people’s agency and power to act for social changes. Similar to the Peruvian public who washed flags in 2000 to symbolize the cleansing of their corrupt national leader, Listen to the City’s workshops spread agencies to make changes for social minorities and prevented fetishization of their reciprocal communication in art institutions. However, like how religious institutions would become the vehicle to elevate objects with their divine power, as William Pietz exemplifies, restricted communication within the gallery space allowed discussions among gallerygoers, limiting Listen to the City’s potential agency for a broader social change outside the art institution.

Second, Mixrice presented and sold its ephemeral video installation at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Korea, through its cooperation with migrant workers in South Korea. Mixrice member Yang Chul-mo’s complex question about how much artists should be compensated by art institutions for allowing their works to be exhibited expands the enigma of whether and how much project participants should be paid. Judith Butler’s theory on performativity, which discusses people’s restricted interpretation of social norms, coincides with Mixrice’s, particularly its member Yang’s, limited understanding of artmaking through material objects, which led to art institutions’ fetishization of the collective’s projects. Mixrice’s installation piece, owned by the MMCA, which collaborated with Bangladesh migrant workers in Korea, is akin to Santiago Sierra’s tattoo drawing on four heroin-addicted female’s backs. As Pietz suggests the correlation between material fetish and human desire, Yang’s presentation of documented materials of his interaction with social minorities at MMCA and sexual harassment/fetish of women co-workers elucidate his performativity and fetishism that disregards human relations but institutional affiliation.[80] Third, unabated permeation of institutional fetishization of social communication was also observed in Okin Collective’s engaging installation at Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. This article elicits the art collective’s affiliation with the corrupt art institution based on Bruno Latour’s mediation and translation through his Actor-Network Theory. Nan Goldin and P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) members’ bold activism eradicated some art institutions’ association with drug companies; their activism outside the museums was to cut the art institutions’ translation of amorality to artists and artworks fetishized in the galleries. On the other hand, Okin Collective ingratiated audiences to visit Leeum to enjoy its installation about artists’ struggle as minorities, despite Samsung’s predatory philistinism over cultural capital through abusing and disregarding its injured workers.

This paper is not simply denunciating art institutions’ fetishization of Listen to the City, Mixrice, and Okin Collective’s socially engaged art. It intends to share the perils of fetishizing social engagement by analyzing the ethology and disposition conveyed in the three collectives’ presentation of their art within art institutions. In transferring the sincere reciprocity with socially marginalized communities into gallery spaces as corporeal forms of art, the value of efficacious problem-solving decreases or is eliminated. Some art collective members disdained ethics and morality during or after communicating with underrepresented people due to their aberrance or loftiness as typified Avant-Garde artists; such events were corollary with art institutions’ systemized fetishization of their art. Despite some tragic causes and effects of fetishized human relations in the Korean art field, the examples and analysis shared in this paper may be a part of their larger practices. Hence, I suggest understanding the cases with such a restriction. Yet, I theoretically analyze these instances to remind artists and art institutions that fetishizing social engagement puts many parties in danger of decreasing reciprocal relationships among communities and deactivating practical social changes for underrepresented people. The pitfall of fetishizing communicative art will recur if socially engaged artists are continuously attracted to institutional presentation and sales of their projects cooperated with socially marginalized groups.

In order to become a socially engaged artist impervious to art institutions or their objectification/fetishization of art, it is critical to configure a working environment and projects where the artist and collaborating subject can coexist ethically and financially. The hardship of cooperation with communities partly relates to the lack of national and regional support for artists and socially engaged projects. The other is partly due to artists’ limited identification of themselves in the art field. Hence, I suggest that artists and art collectives expand their identities beyond the conventional definition of avant-garde artists who present within art institutions. Such interdisciplinary, multifaceted, and hybrid identification could allow wider ways to collaborate with different communities and fund their projects. Lastly, as instantiated in this article, human relations’ entanglement with pecuniary and institutional objectification symptomatically complicates artists’ sincerity toward collaborators and further increases the chance of hurting social minorities. Thus, dissociating art and capital and recuperating sincere reciprocity between people will be paramount to overcoming the contemporary South Korean art scene that fetishizes the aestheticization of human relations.

Jae Hwan Lim is a politically driven artist-activist and historian focusing on human rights and the struggles for democracy in the Korean Peninsula. Researching history and current issues in the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Lim creates socially engaged/dialogic art and writings critiquing violence, discrimination, and inequity in society and politics. Lim is co-founder and director of Humans of North Korea (HNK), an organization that advocates for North Korean defectors’ resettlement and Korea peace, and an editorial collective member of FIELD | A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism. His articles have been published in the Journal of Korean and Asian Arts and Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas – Brill, and he has presented at the Association for Asian Studies, among other platforms. He is a doctoral student in the Art History, Theory, and Criticism Program with a concentration in Art Practice at the University of California, San Diego.

Notes

[1] Namhee Lee, The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea (Cornell University Press, 2009).

[2] Hye-soo Han, “[Interview 4] Yang Chul-Mo: Mixrice – I Neither Hate nor like the Term ‘Post-Minjung,’” The One Art World 44 (June 2016).

[3] Wan-kyung Sung, “The Rise and Fall of Minjung Art,” Hyunsil Publishing Being Political Popular: South Korean Art at the Intersection of Popular Culture and Democracy, 1980-2010 (2012): 189–202., p.198

[4] Tae-won Oh, “The Interaction in Contemporary Art as Seen from the Relational Art of Nicolas Bourriaud – With a Focus on Cases of Inter-Media Art,” Korean Science & Art Forum, March 2018.

[5] TATE, “RELATIONAL AESTHETICS,” ART TERM (blog), n.d., https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/relational-aesthetics.

[6] Grant H. Kester, Beyond the Sovereign Self: Aesthetic Autonomy from the Avant-Garde to Socially Engaged Art (Duke University Press, 2023)., p.180

[7] Sam Gaskin, “Gwangju Biennale 2024 Draws Inspiration from Shamans’ Chants,” Ocula Magazine (blog), June 27, 2023, https://ocula.com/magazine/art-news/gwangju-biennale-2024-pansori-shamans-chants/.

[8] BIENNIAL FOUNDATION, “GWANGJU BIENNALE,” n.d., https://www.biennialfoundation.org/biennials/gwangju-biennale/#:~:text=Founded%20in%201995%20in%20memory,oldest%20biennial%20of%20contemporary%20art.

[9] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Les presses du réel, 2002)., p.31

[10] FIELD MUSEUM, “Field Museum Presents Groundbreaking Exhibition Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories,” FIELD MUSEUM (blog), May 17, 2022, https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/press/field-museum-presents-groundbreaking-exhibition-native-truths-our-voices-our-stories.

[11] Sarah Kuta, “Field Museum Confronts Its Outdated, Insensitive Native American Exhibition,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 26, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/field-museum-confronts-outdated-insensitive-native-american-exhibition-180980148/.

[12] FIELD MUSEUM, “Field Museum Presents Groundbreaking Exhibition Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories.”

[13] FIELD MUSEUM, “Founders & Advocates,” FIELD MUSEUM (blog), n.d., https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/history/founders-advocates.

[14] Emily Sanders, “The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and American Indian Agency,” Cultural Survival (blog), February 1, 2015.

[15] William Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II, The Origin of the Fetish,” The President and Fellows of Harvard College Acting through the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 13 (Spring 1987): 23–45., p.26

[16] Pietz., p.26

[17] RADICAL GUIDE, “Listen to the City,” RADICAL GUIDE (blog), n.d., https://www.radical-guide.com/listing/listen-to-the-city/.

[18] Listen to the City, “Against Distopia Urban Infographic Seminar,” Listen to the City (blog), n.d., https://www.listentothecity.org/filter/project/Against-Distopia-Urban-Infographic-Seminar.

[19] Listen to the City, “Listen to the City | About,” n.d., https://www.listentothecity.org/About.

[20] SEOUL MUSEUM OF ART, “Collection & Art Research / SeMA Collection | No One Left Behind, 2018, Listen to the City,” n.d., https://sema.seoul.go.kr/en/knowledge_research/collection/collection_detail

[21] Listen to the City, “No One Left Behind,” Listen to the City (blog), n.d., https://www.listentothecity.org/filter/project/No-one-left-behind.

[22] Listen to the City.

[23] Seoul Museum of Art, “<Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018> Related Workshop: <No One Left Behind – Disaster Preparation Workshop> Listen to the City,” Facebook (blog), n.d.

[24] Robert Layton, “Art and Agency: A Reassessment,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9, no. 3 (August 11, 2003): 447–64., p.451

[25] Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998)., p.17

[26] Layton, “Art and Agency: A Reassessment.”, p.451

[27] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II, The Origin of the Fetish.” p.30

[28] Pietz., p.30

[29] Choong-geun Yoon, “No One Left behind — Seoul Museum of Art,” n.d., https://cgyoon.kr/No-one-left-behind-Seoul-museum-of-Art.

[30] Yoon.

[31] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II, The Origin of the Fetish.” p.30

[32] Listen to the city conducted “No One Left Behind” workshop in 2019 and 2020 at the NoDeul School for the Disabled, Eun-seon Park, “So no one is left behind, From disaster to recovery | Listen to the City’s ‘Disability Inclusive Disaster Management Project,’” arte365 (blog), November 9, 2020, https://arte365.kr/?p=83147.

[33] “Peruvians Wash Flag as Spy Scandal Grows,” Reuters/CNN, September 15, 2000, https://www.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/americas/09/15/peru.scandal.reut/.

[34] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II, The Origin of the Fetish.” p.30

[35] Listen to the City, “Listen to the City | About.”

[36] Listen to the City, “No One Left Behind — Diabled Inclusive Disaster Preparation Scenario Workshop,” n.d., https://www.listentothecity.org/no-one-left-behind-2.

[37] Ji-won Park, “Award-Winning Artist Vows to Quit after Sexual Harassment Revealed,” The Korea Times, June 21, 2020.

[38] mixrice, “Mixrice | Biography,” n.d., http://mixrice.org/?page_id=1240.

[39] National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, “Mixrice | A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’ | 2009,” n.d., https://www.mmca.go.kr/eng/collections/collectionsDetailPage.do.

[40] National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, “Mixrice | A Song Connected from ‘A Stage’ | 2009,” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (blog), n.d., https://www.mmca.go.kr/eng/collections/collectionsDetailPage.do.

[41] National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

[42] Dong-yeop Yoo, “How Much Should Artists Receive for Participating in a Museum Exhibition?,” Korea Broadcast System (KBS) News, October 18, 2019, https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/pc/view/view.do?ncd=4305563.https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/pc/view/view.do?ncd=4305563

[43] Yoo.

[44] Yoo.

[45] Yoo.

[46] “A Nation Where Artists Literally Starve,” Korea JonngAng Daily, March 1, 2011, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2011/03/01/features/A-nation-where-artists-literally-starve/2932902.html.

[47] Yoo, “How Much Should Artists Receive for Participating in a Museum Exhibition?”

[48] Art Jail, “MMCA Gwacheon <The Square: Art and Society 1900-2019_2, 1950-2019>,” Art Jail: Exhibition-Centered Reviews (blog), November 11, 2019, https://m.blog.naver.com/artgamok/221704850447.

[49] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, II, The Origin of the Fetish.” p.40

[50] Pietz. p.40

[51] MMCA Art Bank, “MMCA Art Bank,” n.d., https://artbank.go.kr/home/eng/contents.do?loc=h11.

[52] TATE, “Santiago Sierra | 160 Cm Line Tattooed on 4 People El Gallo Arte Contemporáneo. Salamanca, Spain. December 2000 | 2000,” TATE (blog), n.d., https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sierra-160-cm-line-tattooed-on-4-people-el-gallo-arte-contemporaneo-salamanca-spain-t11852.

[53] Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (December 1988): 519–31., p.526

[54] William Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, I,” The Univetsity of Chicago Press on Behalf of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, no. Spring (1985): p.5-17. p.10

[55] Park, “Award-Winning Artist Vows to Quit after Sexual Harassment Revealed.”

[56] Park.

[57] Park.

[58] Artforum Artforum News Desk, “ARTISTS JIN SHIU AND YI JOUNGMIN, MEMBERS OF THE OKIN COLLECTIVE, FOUND DEAD,” ARTFORUM (blog), August 20, 2019, https://www.artforum.com/news/artists-jin-shiu-and-yi-joungmin-members-of-the-okin-collective-found-dead-244436/.

[59] Korea Artist Prize, “Okin Collective | Korea Artist Prize,” n.d., http://koreaartistprize.org/en/project/okin-collective/.

[60] Mee-yoo Kwon, “Young Artists Take Look at Modern Society,” The Korea Times, June 6, 2016, https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2023/12/398_206358.html.

[61] Jung-Ah Woo, “Artspectrum 2016,” ARTFORUM (blog), May 12, 2016, https://www.artforum.com/events/leeum-samsung-museum-of-art-220215/.

[62] Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Harvard University Press, 1993)., p.10-11

[63] Shu-Ching Jean Chen, “Samsung Chairman’s Wife Questioned On Artworks,” Forbes, April 3, 2008, https://www.forbes.com/2008/04/03/samsung-slushfund-paintings-face-markets-cx_jc_0403autofacescan01.html?sh=6aaec0f67b36.

[64] CNBC, “Samsung Apologizes over Sicknesses, Deaths of Some Workers,” CNBC, November 23, 2018.

[65] CNBC.

[66] Francis Halsall, “Actor-Network Aesthetics: The Conceptual Rhymes of Bruno Latour and ContemporaryArt,” The Johns Hopkins University Press, Recomposing the Humanities—with BrunoLatour, 47, no. 2/3 (Spring & Summer 2016): 439–61.

[67] Bruno Latour, “On Actor-Network Theory. A Few Clarifications,” Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH Soziale Welt 47 (1996): 369–81., p.375

[68] Latour., p.375

[69] Yeon-soo Kim, “[Leeum ARTSPECTRUM 3 Okin Collective – Kelvin Kyung Kun Park] ‘How much do I sympathize with contemporary art?,’” All About Art 다아트, June 10, 2016, http://aaart.co.kr/news/article.html?no=3129.

[70] Hyung-seok Noh, “With Restructuring, a Debate Rages over Samsung’s Precious Art Collection,” HANKYOREH, April 28, 2016, https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_business/741689.html.

[71] Noh.

[72] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, I.” p.10

[73] Pietz., p.10

[74] So-Young Moon, “Leeum Museum of Art Goes Bananas for Maurizio Cattelan,” Korea JoongAng Daily, February 1, 2023, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/02/01/culture/artsDesign/Maurizio-Cattelan-contemporary-art-leeum/20230201170618952.html.

[75] Chico Harlan, “In S. Korea, the Republic of Samsung,” The Washington Post, December 9, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/in-s-korea-the-republic-of-samsung/2012/12/09/71215420-3de1-11e2-bca3-aadc9b7e29c5_story.html.

[76] Colin Moynihan, “Opioid Protest at Met Museum Targets Donors Connected to OxyContin,” The New York Times, March 10, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/10/us/met-museum-sackler-protest.html.

[77] Masha Gessen, “Nan Goldin Leads a Protest at the Guggenheim Against the Sackler Family,” The New Yorker, February 10, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/nan-goldin-leads-a-protest-at-the-guggenheim-against-the-sackler-family.

[78] I still contend that P.A.I.N.’s activism is the beginning, not the end, of the discourse around art institutions’ affiliation with corrupt capitalistic organizations., Meghan Keneally and Joshua Hoyos, “Sackler Family Pausing Donations as Top Museums Cut Ties to OxyContin Maker,” Abc NEWS, March 26, 2019, https://abcnews.go.com/Health/sackler-family-pausing-donations-top-museums-cut-ties/story?id=61951067.

[79] Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish, I.” p.10

[80] Pietz.