Remembering and Archiving Gijichon: siren eun young jung’s Dongducheon Project and Dalo Hyunjoo Kim’s Ppaeppeol Project

Vicki Kwon

Introduction

This paper discusses art projects that shed light on yanggongju and gijichon. Literally meaning “Western princess,” yangjongju is a pejorative term referring to Korean sex workers for the US military. Literally meaning “military village,” gijichon delineates villages formed around US military camps in South Korea (hereafter Korea unless specified) during and after the Korean War (1950–1953). The US military began to station personnel in South Korea after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War. They took over many former Japanese military bases, as well as infrastructure, after the Korean War. During the golden age of gijichon, in the 1960s, the villages around the US military camps were bustling with people who came to find opportunities to meet the needs of US soldiers. The South Korean government connived in and controlled prostitution inside gijichon for the health and entertainment of US soldiers, because the soldiers were needed for the country’s national defense during the Cold War. In the gijichon, Korean female sex workers and US soldiers, together with their interracial children, lived and worked alongside the village’s residents and business owners. Most of these women came from impoverished families; some of them were war orphans or former “comfort women” for the Japanese military during the Asia-Pacific War. [1] Seven thousand female sex workers were employed during the “golden age” of the gijichon [2] when the US military and the gijichon accounted for 25 percent of the Korean GDP. [3] Many studies describe gijichon as “islands” inside the nation, floating between Korea and the United States, where these women’s human rights were ignored for the sake of Korea’s national defense and development. [4]

Scholars of Korean feminist studies have approached the study of these women in the context of women’s wartime sexual labor, calling them “comfort women for the US military.” [5] Korean society referred to these women with pejorative terms, such as yanggongju (양공주); yangsaeksi (양색시 Western bride); and, even more disdainfully, yanggalbo (양갈보 Western whore). Nowadays, the term gijichon yeoseong (기지촌 여성 gijichon women) is generally used to convey a slightly neutral tone.

The women suffered from daily discrimination and violence, both inside and outside the village. A symbol of gijichon is the building local people called the White House on the Hill (언덕 위의 하얀 집) or the Monkey House (몽키 하우스), located in Bosan-dong, in Dongducheon (Fig. 1). This building was a sexually transmitted disease center that quarantined women to ensure they could not infect the soldiers. Many women died here or suffered from shock from a penicillin overdose. Their human rights were ignored for Korea’s national defense and development. The building still stands as the symbol of gijichons, which remains obsolete as business around the village is no longer as active as before.

As Cho Haeil puts it, gijichon women have long been “the signifier that is a reminder of such feelings as shame, anger, suffering, and helplessness, and the reality of the colonized nation” for Korean men. [6] Contrasting views of these women also existed, in which they were seen as “civilian diplomats” and “patriots who sacrificed their bodies to earn US dollars” that enabled the economic development of the nation. [7] The deaths of the gijichon women were either forgotten or utilized to inculcate patriarchal nationalism by the male-dominant media and activist circles, as seen in the atrocity photos of Yun Geum-I that circulated in the media and remain as the representation of the gijichon women in the public memory sphere.[8]

This paper focuses on two artists’ works that shed light on gijichon and gijichon women: siren eun young jung’s work in Dongducheon and Dalo Hyunjoo Kim’s work in Ppaeppeol. The two artists’ works show different approaches to interacting with the gijichon residents, different ways of presenting their stories as art, and different outcomes. One of the earliest artistic endeavors addressing these women, siren eun young jung’s Narrow Sorrow (2006–2008), was part of the Dongducheon Project, a community art project led by curator Heejin Kim. jung remained an outsider and observer of the village to avoid participating in the objectification and representation of the women. She attempted to document life in Dongducheon by observing and documenting non-verbal language and the background noise of the town. In contrast, Kim settled in Ppaeppeol, a small gijichon village adjacent to Camp Stanley, in the city of Euijeongbu. With her husband and fellow artist Kwanghee Cho, Kim has been practicing community-oriented, process-based art since 2019, interacting and collaborating with the village residents. In this paper, I discuss their practice, focusing on their ethical concerns and artistic strategies in delivering the lived experience of the women and the village residents of gijichon in visual art. I highlight how the two artists strategically avoided representing marginalized people as a spectacle in their visual art, and I discuss the successes of and dilemmas behind the work, situating their work in the community-based art and social participatory art practices in Korean art history.[9]

Dongducheon, Ppaeppeol, and Community Art in Korea

The gijichon of Dongducheon and Ppaeppeol share some similarities. Both were developed by the Japanese colonial administration, which constructed roads and railways to exploit mining and forestry resources. Dongducheon was on the route of the Seoul–Wonsan Railway, which, until the division of the Korean peninsula, connected the capital of South Korea, Seoul, to the port city of Wonsan, in North Korea. [10] The railway now runs from Seoul to Choerwon County, near the border, which lies on the 38th north parallel. Surrounded by mountains, the city of Dongducheon serves as an ideal bastion for a garrison to safeguard Seoul from North Korea. Although it is the name of a city, the term Dongducheon has been used as a synecdoche of all gijichon that formed around US military bases in the city of Dongducheon, such as Bosan-dong, Gwang-an-dong, and Saengyeon-dong Yankee Market. “‘The largest and the most notorious’ among all gijichon,” Dongducheon has housed four infantry divisions since 1955. [11] By the first decade of the twenty-first century, Bosan-dong, the oldest gijichon in Dongducheon, was home to various groups of people, including migrant sex workers from the Philippines and the former Soviet Union and their interracial children. Along with them, migrant workers employed in other businesses, such as manual labor or construction, together with other village residents and business owners, formed internally stratified social classes. [12] Dongducheon is a rapidly developing area, with a highly diverse population in terms of ethnicity.

Ppaeppeol is a small village of the Gosan-dong district in the city of Uijeongbu. Located in the south of the Suraksan mountains and north of Songsan-ro, Ppaeppeol is separated from Camp Stanley by the wall surrounding the camp. The Japanese military had used the site for an airport base, and the US military soon occupied it. The exact roots of the word Ppaeppeol are unclear, but according to residents, it originates from bae (pear) trees or the leaf called ppaeng, both of which were plentiful in the village in the past. Some say the name originates in the history that once people enter, they cannot leave, as the phrase bareul ppaeda (발을 빼다) means pulling one’s foot out. Camp Stanley closed in October 2018, when the US troops moved to the US Army Garrison in Pyeongtaek, south of Seoul. However, the US military still uses Camp Stanley as an intermediate helicopter refueling facility. Ppaeppeol today remains a small and underdeveloped town where senior women who were formerly employed in the sex trade for US soldiers live together with business owners and other village residents.

Development is also pushing the residents of Ppaeppeol to the margins. The long-standing land conflict between the residents and the Lee clan, who own most of the land in the village and charge land taxes, seemed to have been resolved when an agreement was made in early 2019 to sell part of the village’s land to the residents. However, in the process, some indigenous residents who could not afford to purchase the land had to leave. Nowadays, new people moving into the village are migrant workers temporarily employed at construction sites. The village has also seen more bosaljip (shaman house), relating to another group who could not afford the rising housing cost in other areas. Various kinds of minorities in Korean society now live in Ppaeppeol.

The two artists’ projects that are the focus of this paper, in Dongducheon and Ppaeppeol, respectively, are exemplary of the community art or village art that flourished in Korea in the first decade of the 2000s. This community-based and participatory practice also fit the character of the administration of Roh Moo-hyun (2003–2008), which called itself “the participatory government.” Roh’s administration launched “public art projects to enhance the living conditions of marginalized local communities, the Ateu In Siti Peurojekteu” (Art in the City Project), in 2006 as part of its public art policy and annual projects. [13] The Art in the City Project funded community-based art proposals directed by artists collaborating with residents of marginalized communities in order to enhance their living conditions. Such projects shifted the artist’s role from individual creator of an object to educator and facilitator. The project also invited residents into the artmaking process as participants. [14] Various projects received government funding to “enhance” the lives of the marginalized residents. However, most of these projects were outcome oriented. They had a short funding deadline (a problem typical of the Korean arts and culture administration), and most were created through short-lasting interaction with the residents, leaving in doubt what the art contributed to the lives of the community.

The Dongducheon Project (2006–2008) received an Art in the City Project grant. In 2019, nearly ten years after The Dongducheon Project, Dalo Hyunjoo Kim began a series of works in Ppaeppeol. This was after a series of discussions and reflections on community art and village art had taken place in the Korean art scene. How does their work present or deliver the lives of the people in the gijichon differently from mainstream history and media?

The Dongducheon Project and siren eun young jung’s Narrow Sorrows

A community art project led by Heejin Kim, a curator of Insa Art Space, from 2006 to 2008, the Dongducheon Project involved researchers, designers, local activists, and four artists including jung, collaboratively conducting research, site visits, and interviews. The project was part of “Museum as HUB,” an inter-institutional network and partnership program led by the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. The New Museum selected art institutions in five nations to work on their local characteristics, with neighbor as a keyword, and collaborated with and supported them for two years. Kim chose Dongducheon as the locale that shows “the political, social, economic, and historical contradictions and complexities” of Korea. [15] The project resulted in two exhibitions: the first at the New Museum in New York and the second at Insa Art Space in Seoul, both in 2008.

The four artists who participated in the project were Sangdon Kim, Seungwook Koh, Jaewoon Rho, and siren eun youg jung. The project had already been formed with the three male artists, and jung joined later, because the curator, Kim, considered that there was a need to include a female artist and to consider sexuality issues as part of the project. Kim led a performance workshop with residents to initiate communication. Koh staged a performance and created a video at the desolate Sangpaedong Cemetery, where many gijichon women and their children, as well as disenfranchised Koreans and migrant workers, are buried. [16] Koh proposed turning Sangpaedong Cemetery into a public park. [17] Roh developed a piece of web publishing. jung distributed posters that included photographs and text about Dongducheon to provide conceptual context for the audience. [18]

The project shows the artists’ and the curator’s engagement with ethical concerns about making art on gijichon, although some reveal self-contradictory attitudes. According to the curator, Heejin Kim, the project team had to “tirelessly encourage the residents to speak and express various layers of narrative and current issues through various new tools of communication and expression.” [19] For her, all art could do was “to make the residents face the history and reality and provide a nudge to produce in them the desire to communicate on the issues.” [19] The interview continues: “Ultimately, by asking questions about the subjects of Dongducheon through the process of examining the past and present, it was intended to stimulate residents to rediscover their own sense of criticism in creating the local identity of Dongducheon in the future.” [20] Her interview shows self-contradictory attitudes to and an elitist mindset in interacting with the residents of Dongducheon. Although she was aware that “lame edification or an enlightenment approach would not work,” her idea that the residents had no language to speak for themselves and that therefore her team had to encourage the residents to speak reveals the attitude of “aesthetic evangelists,” the type of community artists Grant Kester criticizes for descending into a community like parachute artists, to, in Hal Foster’s term, grant “ideological patronage.” [21]

As the artist whose practice is grounded in feminist practice and the study of sexuality, jung was self-critical about approaching the village residents. Answering my question about these critiques of “aesthetic evangelism” and “parachute artists,” jung said that she was well aware of such risks and was overloaded with ethical concerns in her participation in the project as an outsider elite woman artist trying to make art on the subaltern women. [22] “I should maintain my own ethics as much as I can, and permeate into the community, yet keep a distance, and I should never have a superior position over the people in the community,” says jung. [23]

Grounded in such ethical concerns, jung took different approaches to interacting with the residents from those of the other artists. She refused to take the common way for activists and researchers to meet female sex workers in Dongducheon, which was by purchasing their hours at the club, like the women’s clients do, as this is the only way to meet and converse with the women. [24] jung could not agree with the other male artists’ approach to trying to converse with the residents, which could be seen intrusive to the residents. In her artist statement, she wrote, “Here, I am a random intruder in their living space. Suppressing a twinge of guilt, I try to talk to them casually, and I ask questions in a most polite manner.” [25]

In Dongducheon, jung did not suggest a direct intervention through intrusion or aesthetic change in the village. Instead, she paid attention to what is considered too trivial to merit attention, such as the narrow doors situated between the club buildings in Dongducheon. “The door leads into the club workers’ shabby lodgings. The width of the gate is so narrow that it is difficult to imagine a person passing through it.” [26] jung took the door as a metaphor for the gijichon and the bodies of the women who had once occupied the space and performed day-to-day activities in it, all of which had been neglected in the sphere of public memory. She produced posters titled Narrow Sorrow (Fig. 2a and 2b), which include two photographic images of narrow doors in Dongducheon and a short text.

A single-channel video (14 min 11 sec) (Fig. 3) also titled Narrow Sorrow shows the door from one of the posters and uses various rectangular spaces in the pictorial space, such as signage, the glass top part of the narrow door, and voids above the narrow door and between adjacent buildings to play the video recording of various sites in Dongducheon, including the Sangpaedong cemetery for nameless graves. This video shows two points: mourning and solidarity. A sound piece inserted in the middle is an audio recording of the funerary ritual of the artist’s grandmother. Attending the funeral, which took place during the project, jung felt the irony that some dead are mourned by family members and friends, while some dead are abandoned and forgotten. [27] “I could feel the countless deaths even in the empty streets.” [28] She commented about her feeling of seeing the cemetery for nameless graves, streets that bear stories of women found dead, and the scenes of Filipino women strolling around with US soldiers along the bank of the Sincheon stream. The stream runs from the Hantan River (한탄강), into which bodies of many dead women were thrown. “Even the river is named Hantan River (which can be translated as the river of lamentation), as if Dongducheon was a huge theatrical space for a story on death.” [29] By including both the audio of washing and shrouding her grandmother’s dead body and the scene of the narrow door in Dongducheon, jung provided a mourning ritual for the women who died nameless and were forgotten. [30]

Throughout the video, the soundscape of Dongducheon plays in the background, making the audience pay attention to the sounds of chatting, singing, playing, flirting, and chanting in a hybrid sound of Korean, English, and Tagalog. Therefore, while not presenting the people, the video embraces migrant female sex workers from the Philippines and Russia. jung observed the women’s daytime leisure activities and found that they invite neighbors and sing together. jung wanted to capture this daytime activity, which is the time for self-care and caring for colleagues in solidarity, as a means to form a community, perhaps even as a means to survive. Through observing and documenting non-verbal language and the noises of living, jung highlighted overlooked spaces that remain in Dongducheon as the index of the women who lived behind the narrow doors.

Twinkle, twinkle (2008) is a poem jung composed and then handwrote on paper and installed against a light panel placed against the wall. The light emanating from behind the paper creates the effect of a neon sign or a window. In the exhibition at the Insa Art Space, the poem was installed inside in the staircase, where no actual window existed (Fig. 4). This installation gives a sense of creating a window. It also visually echoes the narrow door in the poster and the video. The poem captures the desire of the women who came from impoverished rural towns to Seoul to earn money, using the metaphor of stars to compare the women to stars that shine on the stage. Highlighting their twinkling moment on the stage, the poem acknowledges gijichon women’s labor as workers in the entertainment business. This poem shows another layer of the lives of gijichon women.

In her work, jung chose neither to (re)present the people in Dongducheon nor to document their stories verbally. She clarified this decision as follows: “Perhaps what was given to the artists during this project was […] to produce another artistic strategy that would have to reject a collective healing strategy to offset all the traumas with victimization and nationalism.” [31] As jung was cautious about othering through the objectification of the Dongducheon residents and spectacularizing them through representation, her work shows the limit of the outsider artist and a “parachuted researcher.” Later, in 2019, in an interview with Ágrafa Society, jung regretted that she had been overly concerned about the ethical aspect of her position as an outsider and an elite woman trying to converse with and represent these women. [32]

During an interview with me, in 2024, jung recalled how this project pushed her to an extreme of self-criticism, to the point that she even considered giving up her career as an artist. [33] jung recalled the moment when she met an artist from abroad who exclaimed, “How cool!” about jung going to the New Museum. She said, “I felt I shouldn’t go to the New Museum by selling Dongducheon.” [34] With the exhibition held in conjunction with the opening of the New Museum’s education program, jung received praise for her video work and its technique, as well as criticism for being too passive as an artist in a public art project. [35] Nevertheless, her work provided the ethical consideration and feminist voice concerning the gijichon women’s lives and desires that was needed for the Dongducheon Project.

Dalo Hyunjoo Kim and Kwanghee Cho: From Mourning to Living

Dalo Hyunjoo Kim uses an entirely different approach to present the lives of gijichon. Previously, she presented mourning for the gijichon women in photographs and films. After moving to Ppaeppeol, she focused on creating daily interactions with the village residents by becoming a community member, diversifying her medium to archiving, facilitating tours, conducting workshops, and creating collaborative theater.

Before Ppaeppeol, from the mid-2010s, her work focused on traumatic memories related to people who had died nameless or had been forgotten, such as the women in Dongducheon and the red-light district in Seoul called Miari Texas Village (미아리 텍사스촌), as well as the victims of civilian massacres before and after the Korean War. [36] She created fictional stories and displayed them in films, poems, photographs, and performance pieces. For example, the three-channel video The Tombs in My Ears (내 귓속에 묻힌 묘지들, 2016–2018) traces a fictional family whose members died during the Korean War. By the end of the film, as the family’s journey ends, the film shows a scene in which a performer dressed in a red hanbok garment with extended sleeves is dancing the salpuri (살풀이 mourning ritual dance). In the artist statement, Kim suggested that her films are a shamanistic ritual in the form of a moving image for those who died unjustly and could not return home.

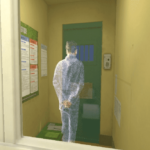

She further developed this idea of mourning in her next solo exhibition, Aedo Yeonseup (애도 연습 Exercise of Mourning), held at Peace Culture Bunker (문화비축기지) in Seoul from December 2018 to January 2019 (Fig. 5). The exhibition traced the feelings of the women who disappeared at the so-called Monkey House. In the exhibition statement, Kim defined mourning as a concrete action and bodily gesture to remember others and to summon the invisible others and internalize them into living bodies. [37] Thus, she titled the show Exercise of Mourning and explained that her current practice of mourning was not a completed action but an exercise that must continue. Her use of film as a medium, tragic history as subject matter, and a shamanic ritual for mourning are common characteristics found in works by many post-Minjung artists dealing with the post-memory of colonization, war, and state violence. [38]

Included in the exhibition as a single-channel video and photographs, Mom Bureum Mal (몸 부름 말 Body, Call, Words) (2018) presents a dance performer and a voice performer, who re-enact the kinds of feelings that the women at the Monkey House must have had, through bodily movement and vocal performance, respectively, based on the script written by Kim. Some scenes in the video show the performer standing inside the Monkey House, which remains a ruin. At another scene, she appears sitting in the Monkey House wrapped in a military blanket. According to Kim, the performer crawling outside the Monkey House is a representation of the artist herself, who tries to enter the space of the silenced women, not from a standing or walking position but from the lowly pose. The role of the voice performer was, according to Kim, not to read or represent the narrative of the women and the space, but to find the voices of these women and let them be heard. A chromatic photographic print hung against a wall shows a woman sitting in a crouched position, with her back exposed. Korean and English letters written on her back from the neck to the low back read yanggalbo, prostitute, patriot, Yellow Monkey, Comfort for the US military, Little Brown Fucking Machine, Dollar box, Yellow Stool, female sex worker—the names these women were referred to as by Koreans. In the artist’s intention, the exhibition was to summon the women and appease them through the artistic mourning practice.

After the show was installed, Kim was ashamed of how she represented the experience of the gijichon women in her Mom Bureum Mal. The trigger for Kim’s shame was a question raised by her fellow female artist: If any of the grandmothers from gijichon were to see the exhibition, what would they think? Kim recalled this moment as if “she were hit by a hammer,” and her work of the past 12 months were “all burned down and fell apart.” [39] For Kim, she was “conscious and careful about the representation of these women’s experience and believed that art could alternatively represent their experience; however, her work ended up being a representation that hurt the women too much.” [40] As she said, her work ended up calling them by such names and summoning them to watch an image of a woman whose body had these names imprinted on her skin. Kim felt ashamed for reproducing the violence. Since then, Kim has critically reflected on her past practice, relying on newspaper articles and others’ research. She decided to join the space where these women live and base her work on the stories of those with whom she interacted.

In 2019, she made her first visit to Durebang, an organization established in 1986 at the entrance to Ppaeppeol to support gijichon women and to eliminate prostitution and military culture. She began to meet the village residents. Since then, she has been working on community-based and process-oriented work with her husband and fellow artist Kwanghee Cho. Kim and Cho rented a small space located on the hill in Ppaeppeol. This space was formerly a bar named Hill Side and was visited mainly by US soldiers, until it closed in 2017. Using the space as a base where any resident could freely visit, Kim and Cho conducted various art, cultural, and educational activities and workshops, hoping to forge a new solidarity with the community through art. Their activities include collecting the village’s archive, including doodling on walls; providing their village tour for visitors; visiting elderly residents; facilitating workshops involving various activities, such as knitting, eating together, and conversing; and documenting the residents’ life stories. In 2021, Kim and Cho renamed the space Ppaeppeol Bogwanso (빼뻘 보관소 Ppaeppeol Archive, Fig. 6) and started using it as a studio and gallery space.

Kim and Cho thrived on creating art and cultural vitality in the village through activities co-created with the residents to communicate their stories and the village’s past and present. One of their early works, Ppaeppeol jureum projecteu (빼뻘 주름 프로젝트 Ppaeppeol Wrinkle Project, 2019), consisted of interviews and activities with the village residents, an exhibition, and a guided walking tour led by Kim. During the tour, titled Ppaeppeol jureum sanchek (빼뻘 주름 산책 Ppaeppeol Wrinkle Walk) (November 2019, Fig. 7), Kim told visitors the stories of the village, visiting venues starting from Durebang, at the entry to the village, to Obok Restaurant and Songsan Banjeom, to the entrance to and wall around Camp Stanley, to the Jeonju Lee clan’s graveyard. Through strolling with people, Kim attempted to include the stories behind the invisible spaces. The tour ended at King Club, where the exhibition Ppaeppeol Wrinkle Project (November 16–30, 2019) displayed photos of the village, accompanied by the stories in text and video recordings of the artists’ interviews with the residents. The project’s title suggests that the project was telling the hidden space and the history of Ppaeppeol, as the meanings surrounding wrinkles imply, physically, a hidden surface between wrinkles and, metaphorically, lifetime hardship, as wrinkles are an index of time, like wrinkles on a grandmother’s hands.

Instead of using visual representations of the former gijichon women to tell their stories, Kim and Cho let the archives and interviews of the residents reveal their stories. For example, menus of local restaurants show changes in the ethnoscape. Chicken ramen and cheese ramen were reflective of a hybridized menu to meet the preferences of US soldiers. Later, the menu changed, reflecting the increasing number of women from the Philippines. [41] The archive and interviews reveal the more complicated landscape of the community. The residents whom the artists interacted with daily include former sex workers, who are now senior women still living in poverty, and similarly impoverished village residents who were once involved in the exploitation of the former to some degree.

The interviews reveal how underprivileged people lived in Ppaeppeol and how the village residents sustained their living through the women, in their own words. For example, Mrs. Jang says, “most residents who live here now made a living thanks to the ladies.” [42] She took over the business of her mom, which rents out rooms to female sex workers. They were the primary visitors to Gosan Jeil Church, and their cash contributions helped the church to flourish. Some successful women who went to the United States with their American husbands even wired money to the church.

Eighty-seven-year-old Jung Namsoo was an uneducated refugee from North Korea and a Korean War orphan, and he worked as a cleaner at Camp Stanley and as a hall manager at a bar. [43] He describes how the village became impoverished after the US camp left and as the Jeonju Lee clan charged land fees. He seems to be a straightforward, hardworking man who overcame a tragic family history but ended up suffering as a resident of a desolate gijichon. However, as the interview goes on, he tells how he made a good income during Ppaeppeol’s peak by renting out rooms to the women, as they needed a private space to serve US soldiers. He mentions having lost a good source of income when Camp Stanley and the women left. Such interviews show the multifaceted lives of the residents.

The artists’ interviews serve as an invaluable oral history, as witness testimonies of the unwelcome history and the lives of the women and the villagers. According to Jung Namsoo, “the village was crawling with the women.” Arguing and brawling between the residents and the US soldiers continued. Police extorted cash from business owners. Women who got syphilis were sent to the Monkey House and then resumed their work. Kim Jangseop describes the community formed by the female sex workers. He recalls fourteen US clubs and five hundred women living in Ppaeppeol until the 1980s. Kim says, “if lucky, the women earn money working there, send the money to the family in the hometown, and eventually move to the United States by marriage. If unlucky, they died of shock from penicillin overdose.” [44] When a woman died from disease or by suicide, the saeksidle (brides; a slightly more friendly term for the sex workers) gathered and conducted the funeral and cremation. [45] Included in a different project by Kim and Cho, titled Hands (2021), is an interview with Jimmy Chu, who bore similar witness as a war orphan. [46] Chu was picked up by a US soldier and then worked at Stanley Camp as a houseboy and a bar hall manager. He shows a positive attitude toward the women, as hardworking neighbors who worked to survive throughout this challenging time, and suggests they deserve better recognition.

Kim and Cho thrived on creating cultural vitality in the village through activities co-created with the residents and on communicating their stories and the village’s past and present. They also invited other artists to stay in Ppaeppeol to learn about the village and its people, and to make art. The exhibition Modeun dareum modeun natseom (모든 다름 모든 낯섦 All Difference, All Unfamiliarity) was held in three venues — Ppaeppeol Archive, Art Space Songsan Banjeom, and Ppaeppeol Community Center—in October 2023. The artists invited were Ahn Sookyung and two artist collectives: Topnee (톱니 Sawtooth) and Gamseonguijeok (감성의적 Emotions Enemies). They stayed in Ppaeppeol for three months to learn about the village and its people and to make art.

Figure 8 shows an installation of VAULT- 006161 by Gamseonguijeok. [47] Inspired by the organic relationship that the members of the artist team created with the residents, they made a sculptural installation in the Ppaeppeol Community Center of a tree that they named “Ppaeppeol Indigenous Tree Species.” Another inspiration for this project was “seedvault,” a compound of seed and vault, referring to a place where humans store genetic resources, such as crops and seeds, for humankind in preparation for disaster. [48] The number 006161 in the title is a passcode that the members of Gamseonguijeok created based on the visual similarity between Arabic numerals and the shape of ㅃㅃ, the consonants of Ppaeppeol in the Korean alphabet, which Kim and Cho use as the logo of the Ppaeppeol Archive. [49] The exhibition invited village residents to enter the password to open a wooden box placed underneath the tree and take some seeds of Myosotis, the flower whose meaning is forget me not, as a souvenir to plant in their garden. Paying attention to the lives of the current village residents over the loaded history of the village, this project opened another possibility for creative collaboration in Ppaeppeol, not around mourning and lamenting the past, but around celebrating the present and seeding hope for the future.

The Voyage of Memory (Fig. 9) in 2023 further extended the possibilities of what community art can do. Directed by Dalo Hyunjoo Kim, the project was created through collaboration with the village residents as the hosts and performers of a theatrical performance, using the village as a theatrical stage to tell their stories. Fifty-six audience members gathered to attend the event the artists called a “moving theater” and “audio-based performance,” once on November 18 and once on November 19, 2023. They watched performances staged at various points in the village, including the basement of a club and the rooftop of a dormitory for sex workers.

Throughout the tour, the audience, wearing headsets, listened to a voice performer reading the scripts telling the story of Ppaeppeol written by Kim and to the residents’ voices telling their own stories. As the audience members walk up the hill, where a woman was killed by a US soldier, the voice recounts that the residents had to climb up the hill to fetch clean water. At the top of the hill, a female performer stages a dance expressing condolences to the dead. The audience continues walking through the village’s alleyways and hears the residents’ voices telling their stories. The group moves to the basement of the Golden Star Club, where most of the lights have been turned off. Upon Kim’s direction, the audience members use their cell phones to shed light on the stage for two performers on the stage: a female tap dancer (who represents the gijichon women) and a male performer (who represents a village resident or a US soldier). The tour has the audience walk up the narrow staircase of the red brick house to the rooftop, making the audience perform the daily activities of the women who lived here in squalid accommodations. On the rooftop, the female performer sings “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” as if enacting a woman who might have come up to the rooftop and yearned for better days. Members of the audience are asked to share their reflections at the end. Village residents read a poem, offer tea to everyone, and invite them to join the reception at Songsan Banjeon, which Kim had turned a closed local restaurant into another cultural space in 2023. A village elder, Park Boksoon, comments that Kim is doing incredible work in the village and asks the audience to give her their support. The Voyage of Memory shows that Kim has earned her good rapport with the village residents, becoming a meaningful community member.

Not everyone was in favor of the artist duo. When Kim and Cho led a project transforming an area in the village made messy due to illegal garbage disposal into a temporary cultural shelter, the landowners misunderstood it as a village revitalization project and opposed it. [50] They reasoned that if the village was revitalized, they would miss out on the opportunities surrounding government-led development and that therefore it should remain like a dead village for now. While some residents welcomed the village becoming clean, the landowners were against the art and culture project in the village.

The risk of objectification of the marginalized is still latent in Kim and Cho’s work, as they began to show the stories of Ppaeppeol in galleries outside the village. In the exhibition Ppaeppeol—sigongeul mongtajyuhada (빼뻘—시공을 몽타쥬하다 Ppaeppeol—Montage Time and Space) held at Uijeongbu Art Camp Black in May 2022, Kim and Cho displayed archive videos, text, and various objects from the village and installed a virtual reality (VR) station. The VR was designed for viewers wearing a VR headset to navigate the village at their own speed and direction. The VR shows Ppaeppeol in aerial and side view and invites the audience to explore various sites within the village, as the viewer is virtually walking through the alleyways, up the narrow staircases of a red brick building, into the King Club, and so on. The audience can navigate the village alleyways and stores; walk down the narrow staircase of the King Club; and see the old signage of the Amazing Club, the Fantastic Club, and the Roxy Club. The voice reads out mundane conversations between Kim and the village residents and archival text, such as the menu of the Stanley House bar. The sound of the Gosan Jeil Church bell rings from time to time.

The way the VR presents Ppaeppeol, by zooming in and out and navigating every alleyway, corner, house, and basement club, seems to be a practice of pressing out the wrinkles in the village. The visualization of untangling and unwrinkling gives a sense of soothing wrinkles and showing the hidden surfaces of the village, thereby presenting the untold stories of the village to the audience. Yet, this work risks showing the village as a ruin. In relation to displaying their work in exhibitions outside the village, Kim and Cho expressed their dilemma in archiving and displaying the village and yet not presenting the work as poverty porn. [51] For that reason, the VR shows no humans, only the old bars, stores, and streets. A medium most often used as a gaming tool, VR might be consumed by the audience as a poverty simulation event. Like with atrocity photos, the one who sees has more power than the one being viewed. When the story of gijichon is presented in a gallery space, the power dynamic between the audience and the residents being displayed needs to be more cautiously considered. The importance of visually documenting the village for the historical archive conflicts with the artists’ concern about objectification of the residents.

Conclusion

The works by siren eun young jung and Dalo Hyunjoo Kim show different approaches to interacting with the gijichon residents, different ways of presenting their stories as art, and different outcomes, while they share mourning and solidarity for the gijichon women as the main theme. To avoid participating in the objectification and representation of the women, jung remained an outsider and observer of the village, keeping her distance from the residents of Dongducheon. As a solution, jung presented life in Dongducheon by paying attention to non-verbal language, as she struggled with ethical concerns approaching and representing the subaltern women as a subject of artmaking. In contrast, Dalo Hyunjoo Kim, along with Kwanghee Cho, became a member of the Ppaeppeol community, by staying in Ppaeppeol and interacting with the residents daily for over years, and created various projects in collaboration with the village residents. Kim and Cho’s Ppaeppeol Project generates more positive and dramatic effects as community art when it is staged within the village and with the residents, and with collaborators and visitors from outside, than as exhibitions in traditional gallery spaces outside Ppaeppeol. Throughout the Dongducheon and Ppaeppeol projects, both jung and Kim were highly self-critical and reflective when working with marginalized communities. Their works present their own solutions, as well as limitations, in presenting gijichon and gijichon women and (un)objectifying them in their displays. These two artists do not simply serve as examples of Korea’s community art practitioners in the 2000s and of post-Minjung art in the 2010s; their ethical concerns led them to seek to overcome the limitation and past practice of community art.

Dr. Vicki Sung-yeon Kwon is an art historian and curator with a research focus on Korean art and visual culture, in relation to global contemporary art, transnationalism, feminist activism, and socially engaged art. She is Associate Curator of Korean Art and Culture at Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Toronto. Prior to joining ROM, she was a postdoctoral fellow of the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, at Seoul National University. She has published her research in the journals Korean Studies, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Asian Studies Review, and Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies. Dr. Kwon is an award-winning instructor. She has taught the arts of Korea, twentieth-century art in East Asia, and art as social practice in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta, where she received her PhD degree in History of Art, Design, and Visual Culture. Since 2023, she has been teaching Korean art history in the Department of Art History at the University of Toronto as a (status-only) Assistant Professor.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the artists siren eun young jung, Dalo Hyunjoo Kim, Kwanghee Cho, and Reina Kwon for their interviews and support for this research. The author also thanks Nan Kim, Meiqin Wang, Jae Hwan Lim, Laura B. Thompson, and the Field editorial collective whose comments greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding

This research was generously supported by the fellowship of Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University, Royal Ontario Museum, and the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism of the Republic of Korea.

Notes

[1] Na-young Lee, “Postcolonial Reading on Military Prostitutes in South Korea: Gendered Nationalism and Politics of Representation,” Journal of Korean Women’s Studies 24, no. 3 (2008): 44–109. (In Korean with English title); Jeong-mi Park, “Development and Sex—The Prostitution Tourism Policy of the Korean Government, 1953–1988,” Korean Journal of Sociology 48, no. 1 (2014): 235–264. (In Korean with English title).

[2] Elim Kim and Young-ja Kwon, “Yullakaengwi deung bangjibeop gaejeongeul wihan yeongute,” [A Study on the Revision of the Act on the Prevention of Pleasant Activities], Yeoseong yeongu 26 (Spring, 1990): 89; Young-ok Kim, “Site-Specific Art Practices as Intervention in the Era of Globalization: Focused on Two ‘Dongducheon’ Art Projects” Yeoseonghaknonjip 27, no. 1 (2010): 83.

[3] Katharine Moon, Sex Among Allies, translated by Lee Jeong-ju (Seoul: Samin, [1997] 2008), 76.

[4] Seok-kyeong Kang, Bamgwa yoram (Seoul: Mineumsa, 1983), 25.

[5] See note 1.

[6] Haeil Cho, America (Seoul: Chaeksesang, [1974] 2007), 289 [In Korean]. English translations of Korean sources are by the author unless noted otherwise.; Quoted from Kim, “Site-Specific Art Practices as Intervention,” 97.

[7] Lee, “Postcolonial Reading on Military Prostitutes in South Korea,” 98; Moon, Sex Among Allies, 155; Yeonja Kim, Amerikataun wangeonni Jukgi Obun Jeonkkaji Ageul Sseuda (Seoul: Samin, 2005), 123; Kim, “Site-Specific Art Practices as Intervention in the Era of Globalization,” 85.

[8] Yun Geum-I was raped and brutally murdered by US Private Kenneth Lee Markle III, in Dongducheon, in 1992.

[9] I intentionally use “social participatory art” to translate Korea’s long history of sahoe chamyeo yeseul (사회참여예술 social participatory art), which is ground in its Minjung art movement from the 1980s, instead of using “socially engaged art”—the term most often used in North American art history, as it was theorized in the 1990s by American and European scholars.

[10] Kim, “Site-Specific Art Practices as Intervention,” 82.

[11] Ibid., 83. As of 2023, there were six US military camps in Dongducheon: Camp Casey, Camp Hovey, Camp Nimble, Camp Mobile, Camp Castle, and the Gymballs Training Court.

[12] Lee, “Postcolonial Reading on Military Prostitutes in South Korea”; Kim, “Site-Specific Art Practices as Intervention,” 84.

[13] This part is based on the author’s PhD dissertation, “Connections in Friction: Socially Engaged Art in East Asia in Transnational Contact Zones,” PhD Diss. (University of Alberta, 2022), 71–72.

[14] For the success and limitations of the Art in the City Project, see Jisuk Hong, “Nomuhyeon Jeongbuwa Gonggongmisul,” (Roh Moo-hyun administration and public art), Naeireul Yeoneun Yeoksa 46 (March 2012): 217–32.

[15] Heejin Kim, “Dongducheon Project: Interview with the Curator,” Community Projects by Artists, Art Council of Korea Webzine, no. 3 (2008): 75.

[16] Young Min Moon called those buried “various social ‘deviants.’” See Young Min Moon, “Report from the Underside: Dongducheon,” Trans Asia Photography 3, no. 1 (2012), https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1215/215820251_3-1-110.

[17] Kim, “Dongducheon Project,” 76.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer?” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 302–9; Grant Kester, “Aesthetic Evangelists: Conversion and Empowerment in Contemporary Community Art,” Afterimage (January 1995): 5–11; Kwon, “Connections in Friction,” 16–17.

[22] Interview with siren eun young jung by the author, January 10, 2024.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] siren eun young jung, “The Narrow Sorrow: Respect for Life, Mourning to Death,” translated by Jae-eun Kwak, artist website, accessed December 31, 2023. http://www.sirenjung.com/index.php/textbymyself/the-narrow-sorrow—-/.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Interview with jung by the author.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] siren eun young jung, “At the End of Dongducheon Project,” Journal BOL 9 (2008): 218. Republished on the artist’s website.

[32] siren eun young jung and Ágrafa Society, “Interview with siren eun young jung: Re-formation and witnessing of performative languages,” Seminar, Issue 2, translated from Korean to English by Hakyung Sim (2019). Accessed December 31, 2023. http://www.zineseminar.com/wp/issue02/interview-with-siren-eun-young-jung-re-formation-and-witnessing-of-performative-languages/.

[33] Interview with jung by the author.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Artist statement of the exhibition The Tombs in My Ears (2016–2018) and Summer in Yugok-ri (2015).

[37] Artist statement of the exhibition Aedo Yeonseup (2018–2019).

[38] For post-Minjung artists’ use of video art to present Korea’s historical injustice, see Myungji Bae, “The Full-Scale Development of Video Art: Korean Video Art Since the 1990s,” trans. Vicki Sung-yeon Kwon, in Korean Art 1900–2020, 455–475 (Seoul: MMCA, 2022).

[39] Interview with Kim and Cho by the author, October 6, 2022.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Interview with Kim and Cho by the author, October 6, 2022.

[42] Kim Hyunju and Cho Kwanghee, Ppaeppeol Wrinkle Project (Seoul: Belongings, 2020), 176.

[43] Kim and Cho, Ppaeppeol Wrinkle Project, 181–184.

[44] Ibid., 209.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “Chu In-kyun shon,” in Dalo Hyunjoo Kim and Kwanghee Cho, Manins Hands: Hands_Groping for Memories and the Future (Seoul: Belongings, 2021), 226–235. (In Korean with English title).

[47] The members of Gamseonguijeok are Reina Kwon, Kiwon Kim, Boram Jung, and Seyeon Hwang.

[48] Artist statement in “2023 Ppaeppeolmaeulpeurojekteu Modeun Dareum Modeun Natseom,” Neolook, October 14, 2023, https://neolook.com/archives/20231014b. Accessed December 30, 2023; Email communication with Reina Kwon, April 12, 2024.

[49] Email communication with Reina Kwon by the author, April 12, 2024.

[50] Interview with Kim and Cho by the author, October 6, 2022.

[51] Ibid.