Dispatch Art as Socially Engaged Radical Art in South Korea

Hong Kal

In October 2010, a construction crane was moved in front of a protest camp at a factory operated by Giryung Electronics. The occupants of the camp were former workers for Giryung who had been fired for organizing a union. Since 2005, they had sought reinstatement and direct employment through sit-ins and hunger strikes. When the police were sent to disperse the protestors by force, they responded by climbing to the top of the crane, where they were out of easy reach. The workers’ cause gained new momentum after this act of resistance, as a group of artists then joined the protest [1]. They decorated the crane with pieces of colorful cloth, workers’ gloves, light bulbs, paper flowers, a dragon head, and banners with slogans. The crane had been sent to the strike site to harass the protesting workers, but the artists turned it into a captivating monument and symbol of their fight, and it cast a radiant glow upon the darkened factory (figure 1). With the artists’ participation, the site of the prolonged labor action was refreshed with a vibrant sense of joyful resistance. One month later, the workers finally reached an agreement with the company, bringing their long protest to a close. Celebrating their victory after 1,895 days of struggle, the workers and artists danced, sang, and enjoyed themselves throughout the night. The artists’ engagement with the strike site had been spontaneous, voluntary, and playful, incorporating humor and satire.[2] However, this victory was ultimately short-lived. Two years later, the CEO of Giryung Electronics cancelled the agreement and permanently shut down the factory. This unfortunate conclusion stands as a poignant reminder of the hardships faced by precarious workers in contemporary South Korea.

The artists who participated in the strike site called themselves “Dispatch Artists” (pagyeon misulga 파견 미술가 ). They chose this name because the term “dispatch” suggested the absolute precarity of labor conditions, and their mission was to provide support for struggles against the forces of neoliberal capitalism, which undermines the very foundation of security in life.[3] This situation took shape following the Asian financial crisis of 1997, when the South Korean government implemented neoliberal reforms such as capital deregulation, privatization, and market-driven policies. The result was a stratification of the workforce and a surge in precarious employment. The precarious employment sector comprises an estimated nine to eleven million workers, accounting for over 40 percent of the total workforce in South Korea.[4] This sort of work, also referred to as irregular or non-regular employment, encompasses various categories including short- and long-term temporary, specialized, and dispatched work. Workers in these areas face reduced job security, benefits, and social safety provisions. Moreover, the practices of subcontracting and outsourcing have further complicated labor relations, as they allow companies to evade legal compliance related to labor. The impacts of precarious employment within the neoliberal paradigm are also felt outside the workplace as broader social and economic inequalities.[5]

The members of the Dispatch Art collective have expertise in various art fields (figure 2). Membership is fluid, adapting to the demands of different protest sites and the availability of resources. Despite this fluidity, the artists are committed to effecting social change through actions that transcend mere social commentary.[6] While many have received formal art education, they position themselves as collaborators alongside other participants on-site and avoid taking up leadership roles with pedagogical intent. They employ diverse art mediums and protest tactics in their engagements, including exhibiting images, banners, and installations, orchestrating performances and events, and occupying sites. Their guerrilla-like actions are often immediate and spontaneous, contrasting with officially funded and meticulous planned large-scale public art projects. Their productions are site-specific, but they are widely shared through blogs and social media platforms. These works convey a subversive and disruptive energy while simultaneously exuding a playful and celebratory spirit. Despite their social significance, however, the Dispatch Artists have so far received little scholarly attention.[7]

Dispatch art is socially engaged art that draws on participatory, collaborative, and dialogical modes.[8] Dispatch art inherited the legacy of the radical minjung (peoples’) art movement of the 1980s,[9] which was focused on social change. Minjung art produced had an emancipatory spirit, expressed through a realistic approach (hyeonsil juui현실주의) grounded in the nation’s history.[10] At the same time, Dispatch art was aligned with community-based public art and the participatory protest culture of the 2000s, when neoliberal capitalism began to be entrenched in the post-democratization era. I approach Dispatch art as a socially engaged, radical form of art that integrates art and activism in the South Korean context. Beginning with a brief history of socially engaged art from the 1980s to the 2000s, I examine the activities of the Dispatch Artists in four contexts: the Yongsan disaster of 2009 in which evictee protesters were killed; the 2011 labor strike against layoffs at Hanjin Heavy Industries in the southern island of Yeongdo near Busan; the 2016-2017 occupation of Gwanghwamun Square in Seoul; and the struggle for labor justice following the tragic death of Kim Yong-kyun, a young irregular worker who died in a workplace accident in 2018. I interweave these empirical case studies of Dispatch art with a critical discussion of socially engaged art in contemporary South Korea.

Socially Engaged Art in South Korea

The formation of socially engaged art in South Korea is closely intertwined with the nation’s turbulent history, from the massive violence attending its foundation, which soon culminated in the Korean War (1950-1953), to a succession of military dictatorships that only ended in the early 1990s. From the late 1950s onwards, the South Korean art scene reflected the strong influence of Cold War politics, in which abstract art was promoted as a visual sign of capitalist democracy and freedom in contrast to the socialist realism prevalent in communist states. The absence of critical social art in this period indicated the prevailing political oppression, anticommunist ideology, and imposed and internalized censorship in South Korea, which heavily impacted artists. As early as 1969, the dominant art system, with its formalist abstract art tendencies, was challenged by a group of artists who declared that “art is a reflection of reality.” Their realist manifesto laid the groundwork for social art movements in the following years. From the late 1970s, many more artist groups were dedicated to fighting against the authoritarian military government. In particular, the Gwangju Free Artists Association strove to expose state violence as exemplified by the Gwangju Massacre of May 1980, stating, “Artists must look at the reality of this land and this time. . . . This is a mandate from conscience.”[11]

Throughout the 1980s, critical-minded artists sought to connect with the lives of the minjung, a term that refers to common people who are historically marginalized but capable of revolting against oppression. In the milieu of dissident social movements, the minjung were recognized as a central subject of history.[12] In their pursuit of the sovereign Korea nation (minjok 민족), democracy (minju 민주), and the people (minjung 민중) as the fundamental pillars of society, minjung artists sought to intervene in the nation’s problematic reality—its colonial legacy, division, military dictatorship, dependency on US imperialism, and capitalist exploitation. They were committed to representing reality and connecting with the minjung, drawing inspiration from folk art, Buddhist painting, shamanic rituals, and Latin American art, characteristically using innovative art mediums such as large banner paintings.

From the mid-1980s, minjung artists focused on participating at protest sites, aligned with the democratization movements unfolding across various sectors of society. Their role was especially prominent during the mass protests in the summer of 1987, known as the June Uprising. During these protests, two college students were killed by the police, and they were memorialized in paintings by minjung artists. These images were carried through the street, hung on buildings, and staged at the center of the mass rallies against General Chun Doo-hwan’s military government (1980-1987). As a result, the iconic portraits became symbols of the democratic movement of the time.

In the wake of the nation’s democratization in the 1990s, the intensity of radical social movements began to diminish, and minjung art organizations and groups voluntarily dissolved. The role of minjung art underwent changes as well. Its museumification was signaled by a 1994 exhibition titled Fifteen Years of Minjung Art: 1980-1994 at the National Museum of Contemporary Art. This officially sanctioned appearance at a national institution indicated the transition of minjung art from a kind of activism into an art object to be exhibited. Social art has continued, but with different methods, ideas, and effects.[13]

A new wave of socially engaged art emerged in the 2000s that incorporated a variety of forms and activities ranging from community murals to local festivals. Active involvement was central to this trend, based on the cultivation of relational atmospheres among community members.[14] The growth of this new community-based public art reflected the nation’s cultural democratization, which necessitated public funding for art that involved people not merely as spectators but also as producers of their own cultural activities. From the mid-2000s, both the central and local governments implemented public art policies and supported various new public art projects especially in economically marginalized areas.[15] The official support for community-based public art coincided with a surge in urban redevelopment, where art was promoted as a potent tool for generating place-making and gaining the associated profits.[16] This initiative embraced the social power of art beyond gallery spaces, but its new concept of collectivity, referred to as keomyuniti (community 커뮤니티), did not engage with the subversive politics associated with the minjung. In this form of engaged art, political agendas often became secondary to “small but certain happiness” (소확행) and in some cases even lost their social relevance entirely, diverging from minjung art.

However, this is not to suggest that mass politics disappeared in South Korea. In the 2000s, as Hyun Ok Park observes, people experienced “a crisis of democratization rather than its progress,” and their discontent sparked protests.[17] The inescapable effects of neoliberal capitalism intensified class polarization and undermined the security of life itself, whether the government was progressive or conservative. Ordinary citizens, from young high school students to mothers pushing baby strollers, responded with collective action facilitated by social media networking. For instance, in 2008, people held carnival-like candlelight vigils to protest the government’s decision to import beef from the United States despite concerns over mad cow disease.[18] The candlelight vigil movements, culminating in 2016-2017, ware a manifestation of frustration and discontent toward South Korea’s system of representative democracy, which the protestors believed was failing to adequately represent them. Individuals sought new avenues for direct participation that were independent from both political parties and major civil society organizations. From a cultural perspective, the “candlelight citizens’ actions” (simin chotbul haengdong 시민 촛불 행동) signified a new mode of protest culture where people created participatory forms of resistance that were both disruptive and festive. By integrating individual fluidity with collective energy, they reinvented social and political activism. At the intersection of this evolving protest culture, the legacy of minjung art, and refined community-based public art, Dispatch art was formed as the embodiment of socially engaged radical art in contemporary South Korea.

Dispatch Art

Despite their different artistic backgrounds and social experiences, the Dispatch artists share the common aspiration to integrate art with activism. They first encountered each other in 2005 in the village of Daechuri located in Pyeongtaek, where land had been designated for the expansion of a US military base as part of its relocation from central Seoul. In solidarity with the village’s residents, who vehemently opposed the government’s expropriation of their land, the artists engaged in various forms of resistance ranging from mural painting to confrontations with the police. While fighting together in Daechuri, the artists had the profound sense that they were part of a “commune,” where “we resisted, stood in solidarity with each other, and felt happiness.”[19] Although the resistance in Daechuri was finally suppressed by the police, the artists’ experience inspired them politically and aesthetically. It gave them the impetus to come together later and form the Dispatch Artists collective. Subsequently, while working with diverse actors at protest sites, they merged art and activism by embracing horizontal relations with their non-artist collaborators. One of the core members, Jeon Mi-young reflected, “Whenever I entered the sites, I was willing to utilize art as a tool because I absorbed artistic energies from there.”[20]

“There are people here” – Fighting alongside Evictees in Yongsan (2009)

On January 23, 2009, the Dispatch Artists, along with other artists and cultural activists, gathered in front of a building barricaded by the police. Named Namil-dang, the four-story building was located in the Fourth District of Yongsan, and protestors were occupying the roof in a demonstration against forced eviction. Under the Lee Myung-bak administration (2008-2013), the district had been designated for urban redevelopment, which involved the large-scale construction of new residential complexes and commercial districts. Soon, in the cold winter of 2008, evictions were carried out despite resistance from some residents and small business tenants, who faced the prospect of considerable financial hardship due to the inadequate compensation they were offered. Those who resisted were subjected to threats, harassment, and violence by thugs hired to drive out the remaining residents and tenants, whose tactics included leaving the carcasses of dead animals in front of the remaining local businesses. On January 19, about thirty people, including tenants and members of the National Association of Demolition Victims, took up highly visible positions on the roof of the building. They set up a lookout tower and began a high-altitude sit-in. Within twenty-five hours, special police forces, who were normally deployed for counterterrorism operations, were sent to suppress the protest. They launched a raid on the building both from the ground and the roof, firing tear gas and water cannons to subdue the protesters. When a group of police attempted to reach the rooftop in a container lifted by a crane, a fire erupted in the lookout tower. Tragically, five protesters and one police officer died in the incident.[21]

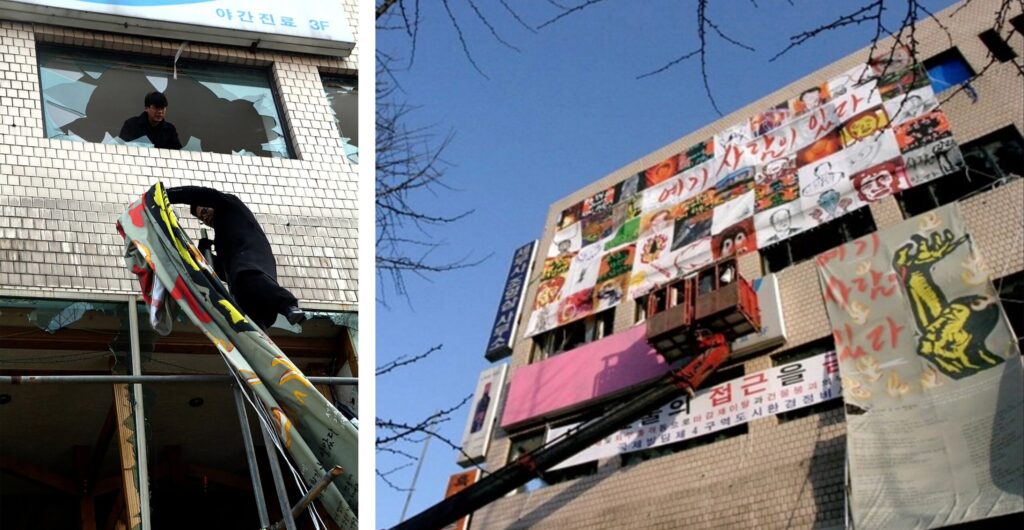

The building, once occupied by people to claim their rights for survival, became a rallying point. The Dispatch Artists and others gathered in front of the building to publicly denounce the city’s violent act of suppression. They broke through the police barricades, and the artists hung a large banner on the building, which was marred with burn marks and broken windows. It had a picture of a figure with an outstretched arm along with the slogan, “There are people here,” echoing the cries of the victims. This image symbolizes the Yongsan disaster and became an icon of continued resistance against forced evictions (figures 3a and 3b).

The police soon announced that the city had been attacked by terrorists, by which they meant the evictee protesters, whom they blamed for the fire. In response, the Dispatch Artists and other activists assembled again in front of the building. After pushing through the police barricades, they hung another banner on the building featuring mosaic portraits of the five victims (figures 3a & 3b). There was a fence on the site that had been erected by the police to prevent access to the building, and the artists covered it with a 25-meter-long white cloth on which they drew portraits of the victims (figure 4). They then quickly made their way inside the building and set up a temporary memorial altar in honor of the victims. With these actions, the artists reclaimed the right to life for those who were unable to survive. The site once occupied by the protesters was turned into a space of resistance that remained even after their deaths.

The police removed the memorial altar and blocked access to the building once again, so the Dispatch Artists found an alternative location nearby. This was a restaurant named Le-a Hof Beer, which had been run by one of the tenants who died during the eviction raid. With the permission of the victim’s family, the artists renamed the building Le-a Gallery and turned it into a meeting space for other grieving families, displaced evictees, activists, artists, and visitors. The store-turned-gallery served as both a memorial and an exhibition space, enshrining the victims’ portraits and holding a series of shows titled Never-ending Art Exhibition. The gallery became a communal space where people gathered to honor the victims, express their grief, exchange personal stories, and discuss how to continue the fight on behalf of both the departed and the survivors (figure 5).[22] Art merged with activism, building a reciprocal relationship.

Nearly a year after the Yongsan disaster, the funeral ceremony for the five tenants took place on January 9, as the government had finally agreed to provide appropriate assistance to the evictees.[23] The funeral procession, attended by a crowd of mourners, presented monumental paintings by the Dispatch Artists, including portraits of the deceased and a depiction of them linking arms and charging forward together (figure 6).

In Yongsan, the Dispatch Artists transformed the traumatic site into a community of solidarity, cultivating an atmosphere where grieving families, remaining evictees, and their advocates interacted through participatory, collaborative, and dialogical forms of engagement. The artists recalled, “Through the engagement, we were reborn as new residents of the Fourth District of Yongsan.”[24] As such, they found themselves part of a community empowered by the integration of art and activism.

“Layoffs are murder” – Solidarity with the Crane Sit-in Strike at Hanjin Heavy Industries (2011)

In 2010, Hanjin Heavy Industries announced its decision to lay off nearly 400 production line workers in its shipbuilding division, citing a business crisis as the reason. On January 6, 2011, to protest the mass layoffs and the sacrifices they imposed on workers, a 51-year-old female welder named Kim Jin-sook climbed up the 35-meter-high Crane No. 85 at the Hanjin shipyard in Yeongdo, an island near Busan.[25] Crane No. 85 had a special meaning. Kim Joo-ik, a union leader, had climbed up the crane in 2003 for his own protest, which ended with his suicide after 129th days. This was followed by another worker jumping off the crane to his death. Kim Jin-sook symbolically aligned herself with her fellow workers’ struggles by climbing up the same crane. As Yoonkyung Lee notes, labor actions adopted distinctive tactics in the 2000s, as precarious workers had to find new ways to assert their demands beyond traditional workplace strikes. The new protest tactics included hunger strikes, head shaving, solitary protests, camp-in protests, long marches, high-altitude protests, and, tragically, even suicides. With such unconventional methods, precarious workers sought to draw public attention to their grievances and desperation.[26]

On April 14, 2011, the 99th day of Kim’s solitary high-altitude sit-in protest, the Dispatch Artists made their way to the Hanjin Heavy Industries shipyard. As soon as they arrived, they spread out an enormous 15-meter banner and painted a figure with her arm stretched upward. This image recalled the one hung on the building where the evictees held their rooftop protest in Yongsan in 2009. This time, the slogan was “Layoffs are murder.” Once it was completed, the artists draped this monumental image on Crane 85 and installed a metal sculpture of the crane’s number, welded by them and the striking workers, in front of it (figure 7). Workers’ gloves, tied to long ropes encircling the crane and swaying in the wind, added a cheerful atmosphere.

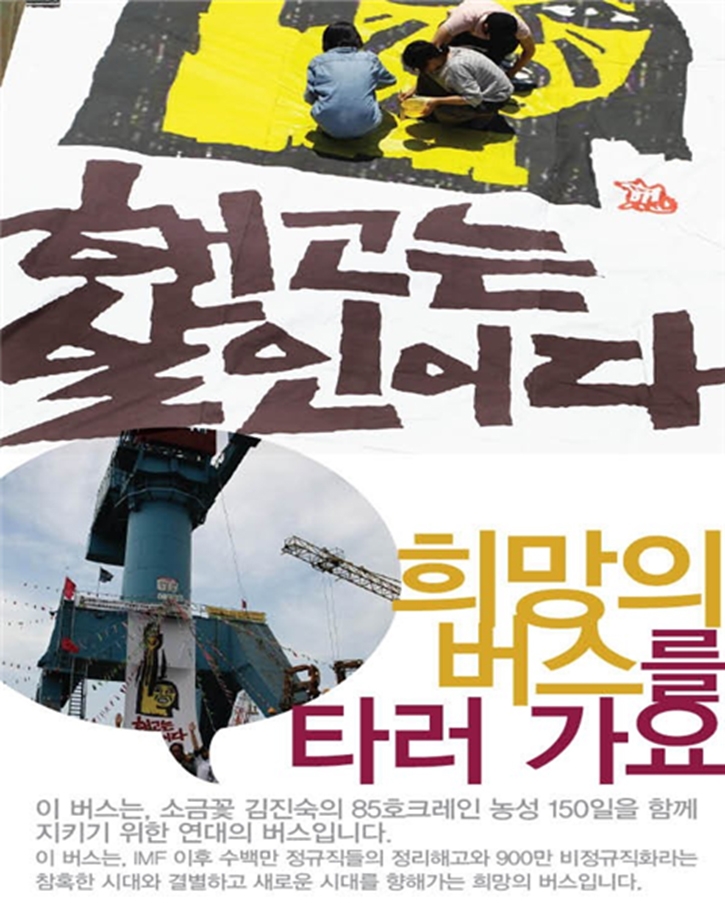

Their involvement continued after the Dispatch Artists returned to Seoul. One of their members, the poet Song Kyong-dong and several others hatched the “Hope Bus” concept, a grassroots campaign to support the Hanjin workers by travelling to the strike site on chartered buses. The name was intended to inspire hope in the face of the workers’ despair. On June 11, 2011, the first Hope Bus departed from Seoul to Busan, carrying passengers who had signed up for the trip through an online café platform created by the artists. An impressive 750 people participated in the journey, so the ticket fees covered travel costs. Although most of the travellers were strangers to each other, an atmosphere of togetherness emerged as they exchanged greetings and shared their reasons for joining (figure 8).

After arriving in Busan at midnight, the participants marched with candles toward the Hanjin Heavy Industries shipyard across the bridge to Yeongdo. At the entrance, they were blocked by police and the company’s private security forces, but they managed to break through. Upon reaching Crane 85 at 3:00 a.m., the striking workers greeted them from atop the crane. Kim Jin-sook called out, “Let’s keep fighting with a smile until the end!” Her trembling, tearful voice moved the crowd to tears as well. The Dispatch team then went into action, hanging banners, installing microphones, and setting up a stage. The space instantly became lively, with music, dancing, singing, and speeches echoing across the shipyard. The strike site was turned into a space for connectedness, solidarity, and joy in resistance (figure 9).

The Dispatch Artists worked tirelessly through the night, preparing for the next day’s activities by crafting pinwheels, arranging banners, readying designs to print on t-shirts, and so on. As the dawn broke, tension enveloped the site. The police issued a warning that they would arrest everyone who had arrived with the Hope Buses. Despite this looming threat, the activists continued to gather, and the artists spread a large banner on the ground again with the message, “People are flowers. We are flowers. Workers are flowers,” accompanied by a picture of flowers in the center. People left their palm prints or posed on the banner to express their solidarity with Kim, who was observing from her perch on the crane. Everyone collaborated on various activities (figure 10). When it was time to return to the buses, the visitors walked back along a farewell path marked by lined-up workers. There was an emotional exchange of hugs and tears. The campaign participants, workers, and artists had all become collaborators in making Dispatch art. The Hope Bus Campaign continued and drew thousands of participants, until the company promised to reinstate 400 workers. Kim finally ended her 309-day protest on November 10 (figure 11).[27]

The Dispatch Artists had taken the initiative to organize the Hope Bus trips, bringing supporters to the remote shipyard in the far south of the country. There, they helped foster a community atmosphere where people expressed solidarity with the striking workers, cheered them on, and channelled their energy into a robust demand for labor rights. As one of the key Dispatch Artists in the campaign, Song Kyong-dong remarked, “The Hope Bus is not a ‘kind’ gesture that reaches out to people in need.” That is, rather than simply applauding out of mere admiration, people came to actively participate in a collective movement fueled by frustration with the precariousness of society. Song further emphasized that “Kim Jin-sook and the workers are beacons of this era, risking their lives to resist the onslaught of capital.”[28] Song was subsequently punished with three-months in prison, while the other Dispatch members received suspended sentences. Hope Busses have since become widespread in grassroots movements for civil-labor solidarity, and they are frequently seen at other strike locations.

Occupying the Square and Reclaiming Sovereignty: The Candlelight Revolution in 2016-2017

From November 2016 to March 2017, millions of people gathered at Gwanghwamun Square in downtown Seoul as well as various locations across the country to demand the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye (2013-2017), who was implicated in multiple crimes involving abuses of power, constitutional violations, and taking bribes from conglomerates such as Samsung. Over the course of five months, an estimated 16 million people participated in these assemblies, signaling widespread public desire for a fundamental reset of the government.[29] These mass protests, known as the Candlelight Revolution, were non-violent yet radical in many respects.[30] The protestors expressed their dissent through handmade picket signs, playful banners, and spontaneous performances, turning the protests into a form of radical participatory art.[31] As Lee Dong-yeon points out, the prominent engagement of artists and artistic demonstrators, who infused the protests with creative dynamics, made the 2016-2017 candlelight protests unique.[32]

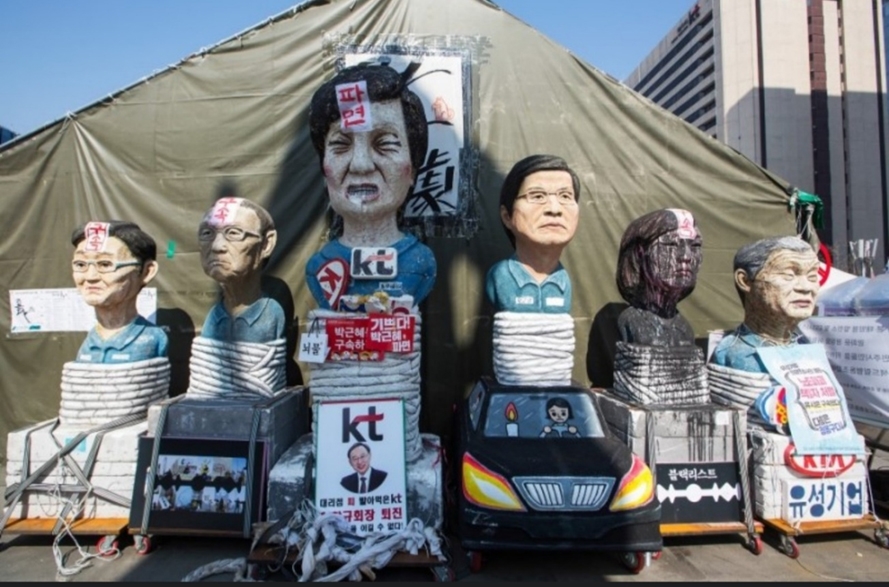

The Gwanghwamun demonstrations began with the assembly of the Gwanghwamun Camping Village, an encampment set up by artists, including those from Dispatch art, as a protest against the Park government’s blacklisting of thousands of artists (figure 12). As the scandals involving Park unfolded, the camp became a visible marker of public occupation in the square, which has historically been an important site of contention between civil society and the state.[33] Throughout the protests, the square was alive with numerous images, installations, and exhibitions, and performances were continually staged in the square both day and night. One example was a group of figures produced by the Dispatch Artists, representing President Park Geun-hye, her inner circle, and Samsung’s vice chairman Lee Jae-yong, all dressed in blue prisoner’s uniforms and bound with ropes. The figures, humorously yet poignantly mocking the accused, were set against the backdrop of national monuments in the square, the nearby Gyeongbok Palace, and the Blue House (residence of the president), further emphasizing the targets of the Candlelight Revolution. They became a focal point in the square and a popular spot for photographs (figure 13).[34] In these ways, the Gwanghwamun Camping Village evolved into a vibrant community of resistance. Reflecting on the experience, Song Kyeong-dong’s statement, “We first ran into the square and held onto it until the end,”[35] captures the resilience of the Dispatch Artists and others who played crucial roles in maintaining the momentum of the protests.

“To Never Die at Work Again” – The Death of Kim Yong-kyun (2018)

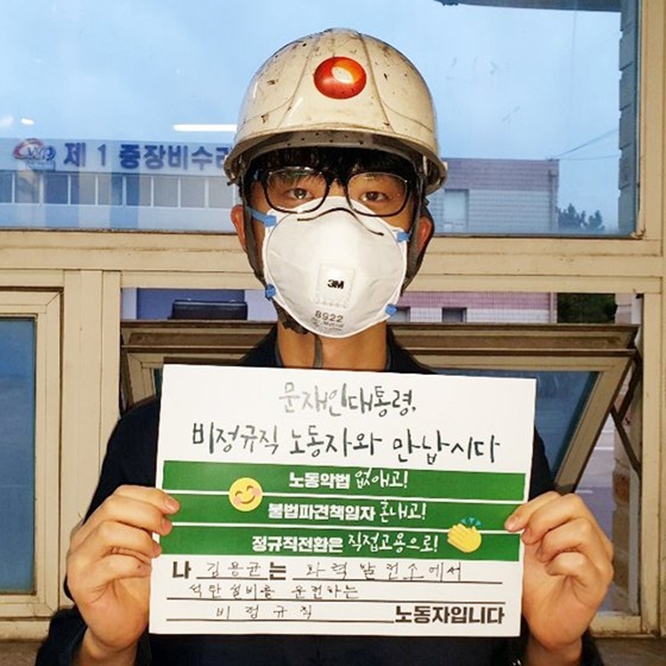

The Candlelight Revolution led to regime change with the election of Moon Jae-in (2017-2022). The new government championed progressive pro-labor policies and vowed to establish a society that respected workers. However, from mid-2018, a shift occurred in its policies concerning economic revitalization and labor market flexibility measures, which began to align more with the conservative predecessors. Frustrated workers took to the streets in protest, sparking a wave of nationwide demonstrations. The catalyst for this movement was the death of Kim Yong-kyun, a 23-year-old precarious worker, in a workplace accident. He was an irregular employee at Taean Thermal Power Plant, located in the southwest region of the country, which was run by Korea Engineering & Power Service (KEPS), a subcontractor under Korea Western Power (KWP). His duties included inspecting a conveyor belt carrying coal and removing any pieces that had fallen underneath. Despite the hazardous conditions in the dark and dusty plant, Kim was underpaid, receiving less than half of as regular employee’s wages, and he did not receive benefits. For these reasons, he took part in a campaign organized by a coalition of precarious workers, in which he held a sign with the messages, “My name is Kim Yong-kyun. I am a precarious worker” and “Stop evil labour laws, punish those responsible for illegal outsourcing, and convert to regular employment through direct hiring.” He took a picture of himself holding the sign as proof and shared it as an expression of solidarity (figure 14).

Two weeks later, on December 10, 2018, Kim lost his life while working at the plant. He was working alone on the night shift, checking the operation of a coal conveyor belt. Due to its hazardous nature, this task should have been carried out by a team of at least two people. Moreover, there were no proper safeguards in place. At some point, he was caught in the machinery and pulled inside the conveyor, which was moving at a speed of five meters per second. Kim’s body was found by a co-worker several hours later. His death had a devastating effect, especially when it was found that he had been a participant in the sign campaign. A fellow plant worker, Lee Tae-seong, wept as he said, “Today, I lost my co-worker. He got stuck in a coal conveyor machine. His body and head were separated.” He further declared, “We, precarious workers, are also citizens. Do not let us be killed.”[36]

While the company attempted to evade responsibility by blaming Kim for the accident, a coalition of workers and advocacy groups demanded an official investigation into the labor practices that led to the tragic accident. At the forefront of the demonstrations was the image of Kim with his sign demanding labor justice, taken just two weeks before the accident. The photo captured a moment in his life and at the same time foreshadowed his untimely death. It was spread widely on and offline and was carried by protesters with such messages as “We are Kim Yong-kyun,” “Stop precarious employment,” and “No more killing” (figure 15).

The Dispatch Artists participated in this collective action by crafting images of Kim in the form of banners, paintings, installations, and statues, representing him not just as a victim but also as a guiding figure illuminating the path toward labor rights.[37] One of the statues portrayed Kim holding his campaign picket sign and standing on the conveyor. It was an active statue that could be moved to different rallying sites (figure 16). This image led his funeral procession, which took place on February 5, 2009, 62 days after his death, following the government’s concession to an outpouring of pressure from the public. Thousands of mourners followed the statue carrying numerous images of Kim. In particular, there was a large painting titled Resurrection of Kim that portrayed him with outstretched arms, symbolizing his new role as an icon for labor justice (figure 17).[38]

The Dispatch Artists played a pivotal role in disseminating images of Kim Yong-kyun, drawing public attention to the stark reality that over two thousand workers, mainly in precarious employment, lose their lives to work-related accidents every year in South Korea. Their art activism helped turn the young worker’s death, which would likely have remained unknown like numerous other industrial fatalities, into a powerful emblem of the battle against labor injustice, thus transcending the confines of mere victimhood.

Contemporary Radical Art

The Dispatch Artists fought for tenants’ rights in Yongsan by collaborating with evictees and their advocates for more than a year, beginning in 2009. Furthermore, their grassroots Hope Bus Campaign transformed a remote strike site into a vibrant space of collective resistance in 2011. In Gwanghwamun Square, they were heavily involved in the Blacklisted Artists’ Encampment, which evolved into the mass protests called the Candlelight Revolution in 2016-2017. Soon after, the artists returned to the streets, bringing public attention to the dire labor conditions faced by irregular workers. They addressed urgent social issues through artistic and cultural initiatives in collaboration with various other actors and sought to build communities of solidarity for social change.

The Dispatch Artists inherited minjung art, which grappled with social realities, advocated for marginalized people, and intervened in sites of conflict, thereby contributing to radical social movements. The influence of minjung art is particularly evident in the powerful images created by the Dispatch Artists for protest rallies and funerals. These images recall the iconic portraits of victims of state violence produced by minjung artists, which were displayed at the center of the mass democratization protests in the 1980s. At the same time, Dispatch artists distanced themselves from the historical minjung art. While they continued to use representational forms, they also explored process-driven methods that reflected the dynamics at protest sites. Despite their occasional involvement with civil society organizations and labor unions, they avoided taking top-down directives from any group. Instead, they employed a fluid approach that allowed them to adjust to changing circumstances and position themselves as collaborators rather than “emancipatory” leaders at protest sites.

Dispatch art is characterized by participatory, dialogical, and process-based practices that are more spontaneous and responsive to specific site conditions than previously funded and planned community-based public art projects. What distinguishes most Dispatch art from other socially engaged art is its dedication to activism and political intervention. While it experiments with contemporary practices of engaged art, Dispatch art upholds a spirit of radicalism. Its guerrilla-style actions, both playful and subversive, are aligned with the new civic activism in which individual participants come together in solidarity against social injustices. The messages exhibited in Dispatch art, such as “There are people here,” “Layoffs are murder,” and “To work without dying,” derive from the politics of living. According to Hyun Ok Park, this politics has become a new aspect of the struggle against the state and neoliberal capital in the 2000s, as they have helped make life itself insecure. As Park explains, “Workers’ expulsion from unionized jobs, rented stores, or land from the 2000s on has been defined as the loss of life itself, going beyond issue-based protests to challenge modern biopolitics itself.”[39]

At the intersection of historical minjung art, innovative community-based public art, and the new protest culture, Dispatch art has emerged as a form of socially engaged art activism dedicated to fighting for the lives of the people against the state and neoliberal capital. Despite the significance of their work, the activities of the Dispatch Artists have become infrequent. The precarious living and working conditions they face have made it difficult for them to survive as activist artists. Nevertheless, they persist. The poet Song Kyong-dong stated, “Someday, the tree of freedom will bear fruit. Until then, the dreams and experiments of the Dispatch art team will continue. Someday, the small communes and their memories and struggles will come together, paving the way toward a liberated future.”[40] In contemporary South Korea, conservative authoritarian forces regained power in the 2022 elections, overturning the previous government that, despite support from the Candlelight Revolution, fell short of achieving its promises of reform. In the present climate, as people are gathering again in public spaces amid economic challenges and political discontent, a resurgence of radical art is anticipated.

Hong Kal is an Associate Professor in the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University. She has explored the roles of colonial expositions, museums, memorials, and urban environments in shaping Korean national identities, linking concepts of visual spectacle, urban space, and cultural politics. Her work includes Aesthetic Constructions of Korean Nationalism: Spectacle, Politics, and History (Routledge, 2011). Her ongoing research focuses on the visual representations of historical and social traumas. Currently, she is working on a book project titled Visualizing Griefs: Mediating Violence and Trauma in South Korea.

Acknowledgements: I would like to express my gratitude to the Dispatch Artists for letting me interview them and generously sharing their experiences and insights. I am also grateful to Chung Taekyong and others who granted me permission to use their photographs, and Yoon Jin Jung who edited photographs. My thanks go to Jae Hwan Lim, Noni Brynjolson, and the other editorial team members at the journal Field.

Notes:

[1] In this paper, the names of Koreans residing in Korea are written with the surname preceding the given name.

[2] Jin-gyeong Jeon, interview with the author, October 18, 2023. See also “Pagyeon latte: pokeulleinui byeonsineun mujoe!: giryung jeonja bunhoe tujaeng 1895il geurigo..” [Papyeon latte: the metamorphosis of excavator is innocent! Giryung Electronics workers’ struggle for 1,895 days, and..], Munhwa yeondae [Cultural action], October 25 2023. https://brunch.co.kr/@culturalaction/98.

[3] Yu-a Shin, “Pagyeon misul hyeonjang misul yeongjaereul sijakhamyeo” [Beginning the series on Dispatch art and site art], Munhwa yeondae [Cultural action], May 16, 2017, https://culturalaction.org/39/?idx=3851879&bmode=view.

[4] Yu-seon Kim, “Bijeonggyujik gyumo wa siltae” [The scope and reality of precarious employment], KLSA Issue Paper, December 1, 2022: 1–29.

[5] Yoonkyung Lee, “Labor Movements in Neoliberal Korea: Organizing Precarious Workers and Inventing New Repertoires of Contention,” Korean Journal 61, 4 (2021): 44–74.

[6] The Dispatch Art collective included the late Gu Bon-ju (sculptor), Jeon Jin-gyeong (painter), Jeon Mi-young (sculptor), Kim Hyun-suk (graphic novelist), the late Lee Yun-gi (painter), Lee Yun-yeop (painter), Na Gyu-hwan (sculptor), Noh Suntaek (photographer), Shin Yu-a (cultural activist), and Song Kyeong-dong (poet), among others. These artists participated at many protest sites, where they helped advance labor rights and social justice. They were involved in causes connected to Giryung Electronics, the Yongsan fire, Ssangyong Motors, Daewoo GM, Colt-Coltec, Hanjin Heavy Industries, Gangjeong Village in Jeju Island, the Sewol Ferry sinking, the Gwanghwamun Square occupation, and many others.

[7] For previous work on the Dispatch Artists, see Jong-gil Kim, “Yeogi sarami itda” [There are people here], Munhwa bipyeong (2011): 367–77 and “Pagyeonmisulgwa pagyeonmisulga” [Dispatch art and dispatch artists], Ateuporeomri (2012). See also Jae Hwan Lim, “Dispatching Art: Building Peaceful Solidarity with Laid-Off South Korean Workers,” Journal of Korean and Asian Arts 7 (Fall 2023): 45–82.

[8] For global contexts of socially engaged art, see Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011) and Beyond the Sovereign Self: Aesthetic Autonomy from the Avant-Garde to Socially Engaged Art (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2024). For East Asian cases, see Meiqin Wang, ed., Space, Place, and Community: Public Art in East Asia (Wilmington: Vernon Press, 2022).

[9] Yu-a Shin, “Pagyeon misul hyeonjang misul yeongjaereul sijakhamyeo” [Beginning the series on Dispatch art and site art].

[10] For minjung art, see Jong-gil Kim, “80 nyeon-dae minjung misuleul dasi saenggakhanda” [Rethinking minjung art in the 1980s], Minjok mihak 11, 2 (2012): 111-48 and “Minjung art movement in the 1980s,” in Looking at the Korean Art Again 2: 1980s, edited by Park young-taek, Lee Seon-yeong, and Lim San (Seoul: Hyeonsil Munhwa Yeongu, 2022): 17–37.

[11] Kim, “80 nyeon-dae minjung misuleul dasi saenggakhanda” [Rethinking minjung art in the 1980s]: 124.

[12] Namhee Lee, The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011).

[13] Chunghoon Shin, “Reality and Utterance: In and Against Minjung Art,” in Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation and Interaction, ed. Y.S. Chung, S. Kim, K. Chung, K. Wagner (London: Phaidon, 2020): 98–115.

[14] Mi-yeon Park, “Silcheon euroseo ui yesul: Hanguk keomyuniti ateu-ui sanghwang” [Art as practice: situations of Korean community art], Yesul Gyeong Yeongu 27, (2013): 75–99.

[15] Two notable examples were the Anyang Public Art Project (2000-2010), hosted by the city of Anyang, and the Maeul Art Project (2009-2010), sponsored by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism across 36 localities. See Yu-jin Kim, “Local sidae ui gonggong misul: 2000 nyeondae ihu Hanguk gonggong misul eseo gonggongseong ui uimi byeonhwa” [Public art in the local era: changing meanings of publicness in Korean public art since the 2000s], Misulsa Yeongu 32, 2017: 189–219.

[16] Hong Kal, “Public Art of Occupation in Contemporary Korea,” in Space, Place, and Community: Public Art in East Asia, ed. Meiqin Wang (Wilmington: Vernon Press, 2022): 211–40.

[17] Hyun Ok Park, “The Politics of Time: The Sewol Ferry Disaster and the Disaster of Democracy,” The Journal of Asian Studies 81 (2022): 131–44 and “Candlelight Revolution (South Korea),” in Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, ed. D. Snow, D. Portta, D. McAdam, and B. Klandermans (Wiley-Blackwell; 2nd edition, 2022): 1–4.

[18] Dongyeon Lee, “Chotbul ui rideum, gwangjang ui munhwa yeokdong” [The rhythm of candlelight, cultural dynamics of the square], Markeuseujuui Yeongu 14, no. 1 (2017): 91–117.

[19] Kyeong-dong Song, “Kkeunnaji anneun jeonsi opeun seutyudio” [The Never-ending Exhibition Open Studio], the exhibition held by three Dispatch artists, Na Gyu-hwan, Lee Yun-gi, and Jeon Mi-young, in June 2023.

[20] Mi-young Jeon, interview with the author, May 3, 2023.

[21] Artists at the Yongsan disaster, Yongsan chamsa chumo pagyeon misul heonjeongjip: kkeunnaji anneun jeonsi [Dispatch art’s tribute to the Yongsan disaster: the never-ending exhibition] (Seoul: Salmi Boineun Chang, 2010).

[22] Ibid.

[23] It took a decade for the government to officially acknowledge that the catastrophe was caused by excessive police force. The new findings disclosed that the rushed operation to suppress the protest had not been necessary, and the focus by the police on making arrests instead of prioritizing safety, despite the foreseeable risks, was a breach of protocol. Despite these findings, the government did not deem either the police or prosecution to be criminally liable, bringing a frustrating conclusion to the case. This result—revealing the facts yet failing to bring the responsible parties to justice—deepened the trauma for those who had been violently evicted.

[24] Mi-young Jeon, interview with the author, May 3, 2023.

[25] Kim Jin-sook was hired as the first female welder at Daehan Shipbuilding Co. (now Hanjin Heavy Industries) in 1981. She was elected as a union representative in 1986, and in the same year, she was detained and tortured by the National Security Agency three times. She was unfairly dismissed from her job that year. In 2009, the Committee for the Restoration of Honor and Compensation for Democracy Movement Participants recognized her union activities as part of the democratization movement and stated that her dismissal was unjust. It recommended her reinstatement, but the company refused.

[26] Yoonkyung Lee, “Sky protest: New forms of Labor Resistance in Neoliberal Korea,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45, no. 3 (2014): 443–64.

[27] Yu-a Shin, “Pagyeon misul yeonjae 14: kkal kkal kkal huimang beoseu chulbal” [Dispatch Art series 14: The departure of the Hope Bus], Munhwa yeondae [Cultural action], (August 16, 2017). https://culturalaction.org/103/?idx=3852525&bmode=view.

Yu-a Shin, “Pagyeon misul yeonjae 15: kkal kkal kkal huimang beoseu yeongdoui bameun gamdong” [Dispatch Art series 15: the Hope Bus, an impressive night in Yeongdo], Munhwa yeondae [Cultural action], (August 21, 2017). https://culturalaction.org/103/?idx=3852526&bmode=view.

[28] Dae-hyun Kim, “Siin Song Kyeong-dong gwaui daehwa” [Conversation with the poet Song Kyeong-dong], New Radical Review 2, no. 2 (Summer 2022): 189–211, 208.

[29] The protests were organized by the Emergency National Action, comprising more than 2,300 civil society organizations, and supported by on-the-spot donations from the assembled participants.

[30] The encampment in Gwanghwamun Square can be compared with Occupy Wall Street in New York City in late 2011 and early 2012. They shared some protest strategies, including the rhetoric of occupation, the seizure of public spaces, encampments, the presence of anonymous individuals, the staging of radical equality, and festive performances. However, despite these shared aspects, the South Korean case exceeded Occupy in its duration, the scale of participation (with millions of people), and political impact, as it led to the impeachment of Park Geun-hye and a new administration.

[31] Kal, “Public Art of Occupation in Contemporary Korea.”

[32] Lee, “Chotbul ui rideum, gwangjang ui munhwa yeokdong” [The rhythm of candlelight, cultural dynamics of the square].

[33] Kal, “Public Art of Occupation in Contemporary Korea.”

[34] Gyu-hwan Na, interview with the author, May 12, 2023.

[35] Kyeong-dong Song, interview with author, April 8, 2024.

[36] Mi-jeong Kwon, Limbo, and Huieum, eds., Kim Yong-kyun, Kim Yong-kyundeul [Kim Yong-kyun, Kim Yong-kyuns], (Seoul: Oworui Bom, 2022).

[37] Yoonkyung Lee, “From ‘We are Not Machines, We are Humans’ to ‘We are Workers, We Want to Work’: The Changing Notion of Labor Rights in Korea, the 1980s to the 2008,” in Rights Claiming in South Korea, eds. C.L. Arrington and P. Goedde Rights, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021): 195–216, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108893947.

[38] The White paper team of the Citizens’ Committee for the Investigation of Kim Yong-kyun’s Death, Kim Yong-kyun iraneun bit 1: girokgwa gieong [The light of Kim Yong-kyun 1: Records and Memories] (Seoul. 2019).

[39] Park, “The Politics of Time”: 132.

[40] Song, “Exhibition statement: The Never-ending Exhibition Open Studio.”