Art and Activism in Boyle Heights

By Erika Barbosa and Noni Brynjolson

For the past several years, community groups have protested the presence of art galleries in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, linking them to gentrification and displacement. Their tactics have involved organizing boycotts and picket lines, occupying art galleries, and various forms of online activism. These protests have been marked by their intensity as well as their seeming effectiveness, with numerous galleries having closed or moved in the past few years. The protest tactics have been the subject of heated debate, in part because of the perceived unwillingness of activists to negotiate or engage in dialogue with artists and gallerists. This anti-gentrification organizing has roots in earlier struggles and past conflicts over space, race and development in the neighborhood. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Boyle Heights was one of the only places in Los Angeles where people of color were allowed to purchase property as a result of city-wide racist housing covenants.[1] Prior to World War II, Boyle Heights was home to many immigrant communities including Jewish, Eastern and Southern European, Japanese American and Mexican American populations. By the 1960s, it was a majority Latino community, and became a cultural and political center for the Chicano movement. The anti-displacement protests of today can also be understood in light of protests over the closure of several public housing projects in the 1990s, as well as the neighborhood’s troubled history with transportation development. Massive highway infrastructure tore through Boyle Heights in the 1950s and ‘60s, displacing more than fifteen thousand residents, degrading green space, and bringing a disproportionate environmental health burden to the neighborhood.[2]

Recent protest groups have described gentrification as a form of cultural colonization and as a serious threat to the neighborhood’s low-income, predominantly Latinx/Chicanx residents, many of whom have experienced rent increases or eviction, and intimidation from police or immigration officials. Issues of cultural colonization may be traced back to nuanced complications with Eastside railway expansion proposals around the turn of the twenty-first century, which coincided with the LA County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro)’s efforts to map Boyle Heights’ Mexican and Latinx heritage through urban planning interventions and the construction of cultural monuments. In the early 1990s, Metro acquired real estate around the First and Boyle street juncture, a hub for local commerce activities. The acquisition was part of a railway expansion plan that ultimately fell through, but left Metro as a major stakeholder in the community. Subsequent to this land acquisition, a group of local artists and community organizers worked with Metro on a Cultural Needs Assessment document (1995), which advocated strongly for development that reflects east Los Angeles Mexican and Latinx heritage, arguing that “community cultural and art components had to play a key role in the architectural and urban design elements” of railway expansion in the neighborhood.[3] This advocacy informed the making of several cultural monuments, including Mariachi Plaza in the early 2000s: a forty-foot domed plaza designed by Mexican sculptor, Pablo Salas. Mariachi Plaza pays homage to the century-long tradition of Mariachis living and working around the juncture. The plaza was designed to be one facet of a public space and transportation complex, with a light rail station connecting Boyle Heights to Downtown for the first time since the early 1900s. But the plaza remained half realized, without a connecting railway station for more than a decade. Urban planner James Rojas describes the plaza in the late 1990s as sitting awkwardly in the middle of the traffic island, surrounded by the rest of Metro’s vacant land, which had erased all the previous community serving activities. For those few years, the First and Boyle juncture “languished like a bad relationship between Metro and the community,” until the arrival of the railway extension in 2009.[4] This relationship was further complicated in the 2010s, after the city designated the Boyle Hotel a Historic-Cultural Landmark, causing the mariachis who lived in the hotel to relocate for two years due to renovations. Although monuments like Mariachi Plaza and the Boyle Hotel have become valuable cultural assets that reflect the community, their execution inadvertently destabilized local residents and economies in various ways. The monuments dedicated to mariachi culture have not protected local musicians from the redevelopment plans and rising property values that continue to change the landscape.

With a number of galleries in Boyle Heights having recently closed or moved, one might wonder if the activists have won their battle, and if the tide of development is turning. If so, can this example be seen as a blueprint for future anti-gentrification struggles? Or will the presence of other large-scale, non-arts related development in the neighborhood outweigh these events? What are the implications of these struggles for artists whose work engages with various forms of activism, and who see themselves as both committed to social justice issues, and complicit with the art world? While debates about gentrification and the neo-liberalization of urban space are taking place in cities around the world right now, struggles in Boyle Heights are unique because of the degree to which art has been connected to gentrification and displacement, and the concrete results that have been achieved by protest groups so far.

This issue of FIELD explores these debates through a range of essays and interviews that reflect upon the broader aesthetic, political and social implications of these protests. In discussions of art and activism in Los Angeles, much attention has focused on Defend Boyle Heights, a group committed to resisting gentrification in the neighborhood. Defend Boyle Heights reconstituted its membership in December 2018, in order to deal with “intense internal conflicts.”[5] In doing so, it has clarified its politics as communist and Maoist, using terms such as “wreckers” and “struggle session” in numerous online posts. Members of the group believe that the only solution to gentrification is revolution—to destroy capitalism and the state, and its corrupt institutions. The group has taken a strong position against identity politics, arguing that one’s political beliefs are more important than identity. Yet, it has proven difficult for Defend Boyle Heights to build a mass movement, or maintain coalitions with seemingly like-minded organizations.

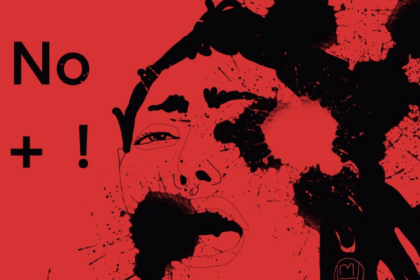

For example, in Spring 2019, a conflict emerged with the OVAS, formerly known as the Ovarian-Psycos, a Women of Color “bicycle brigade” that has existed in the community for several years prior to the formation of Defend Boyle Heights. Defend Boyle Heights called for a total “political isolation” of the OVAS, criticizing them as overly invested in identity politics. Members of both groups accused each other of engaging in petty personal conflicts, and being hypocrites and sell-outs. Defend Boyle Heights has committed itself to a deliberately black and white approach: you’re either with us or against us. Leonardo Vilchis, a community organizer who works with Union de Vecinos, has echoed this statement by emphasizing the importance of refusal—of saying no to development, no to compromise, no to coalition building that might dilute or infect the politics of the movement.[6] The conflict between these groups is a good illustration of issues that plague the broader left—fracturing between identity-based and class-based approaches, and the struggle between acknowledging the complex nature of social struggle, and adhering to an ideologically purist approach in order to resist the corrupting nature of capitalism.

Where does art stand within this logic? According to Defend Boyle Heights, art is either produced by “the capitalists and their supporters” or “the workers and our allies,” and “all artists, all students, all activists, all teachers, all people, can only fall into one of the two categories.”[7] There is no in between. This tactic of choosing sides and maintaining their fundamentally antagonistic nature can be claimed as successful because it has led to the closure of five art galleries in Boyle Heights since 2017, and because of the large community of online supporters that the group has accumulated (many of whom live in the neighborhood, although there are also numerous supporters from other neighborhoods, cities and countries). In this issue, a number of different authors, artists and collectives reflect on the role of art and activism in Boyle Heights and in other parts of Greater Los Angeles, reflecting a diversity of opinions and perspectives—often preferring the murky complexities of the grey zone as opposed to black and white. Many of the contributors are linked through their participation in both the art world and their participation in different forms of activism or community organizing (this is the case with numerous members of the protest groups as well, as some critics have noted). Some of the authors included in this issue view these roles as separate, while others see them as one and the same. Some have attempted to theorize ways in which their commitment to one world informs the other—for example, by suggesting different social roles for artists vs. activists, or by questioning the autonomy and freedom associated with making art, proposing instead, a vision of art that is more committed to social justice and community needs.

A conversation with Los Angeles based artist and writer, Evan Kleekamp, explores questions of artistic autonomy in the context of community engagement. In 2017, Kleekamp worked at 356 Mission, a former artist-run exhibition space in Boyle Heights that faced vehement resistance from activist coalitions. 356 Mission was co-founded by visual artist Laura Owens and Ooga Booga bookstore owner, Wendy Yao in 2013. It came under intense scrutiny by the activists, as part of their broader protest against the gallery’s building owner, Vera Campbell, who owns several parcels of real estate along the industrial western edge of Boyle Heights. Yet the artists leasing the space faced the brunt of resistance and criticism. For organizers of Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement, the very presence of metropolitan galleries is unequivocally detrimental to the community because “development and real estate speculators have their eyes trained on the arrival of artists as the moment to start accumulating property.”[8] For Kleekamp, the link between the galleries and gentrification is symptomatic of larger real estate authorities and city-level development patterns impacting the neighborhood: “anyone who has been watching the situation knows that the artists are a pale threat in the face of the forthcoming development that will cater to the tech industries Los Angeles has been trying to attract.” Indeed, the same western corridor where 356 Mission once was, is now a part of a rezoning plan that aims to revitalize the area into an “Innovation District,” calling for green industries and biotechnology to move in.[9] In the years leading up to the gallery’s closure, the protests became fodder for editorials debating the politics of complicity for participating artists. But what can be gleaned from the exhibitions and programs that did take place at 356 Mission? Kleekamp argues that as an artist-run enterprise, 356 provoked the possibility of greater economic autonomy for artists, while endeavoring to make exhibition space more accessible to a wider community of showing artists in a city whose art market is increasingly elitist and impenetrable.

In their essay the members of Ultra-red examine the history of community organizing in Boyle Heights, pointing to one of the major issues they see affecting debates over gentrification today: the erasure of the agency of the poor in news accounts of the struggles. They argue for the importance of recognizing the role of public housing residents, going back to the struggle for Pico Aliso in the 1990s, many of whom were Latina immigrants. They reference Norman Klein’s book The History of Forgetting: Los Angeles and the Erasure of Memory, and argue that contrary to its title, “when a community spends two decades struggling against the destruction and privatization of public housing, little is forgotten.” They discuss the importance of “naming the moment,” and acknowledging the current conditions associated with gentrification and displacement. In the context of Los Angeles this acknowledgement must address the effects of mega-development and the growth of the entertainment economy and arts districts, as well as the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment, ICE raids and xenophobia towards people of color, demonstrated by the most recent white nationalist mass murder targeting the Latinx community in El Paso, Texas. In this context, Ultra-red creates work that is focused on listening and dialogue, emphasizing the importance of recognizing the complex nature of identity and class struggle. They argue for the importance of understanding the broader political economy of galleries, and discuss the role of autonomy in art, asking “When artists feel that their freedom is threatened by the resistance to artwashing, it seems to us that such a feeling poses important questions. What does it mean to be an artist at this historic juncture of neoliberalism, racism, gendered violence, and state authoritarianism?”

John Hulsey and Shmuel Gonzalez also examine the history of Boyle Heights, in a conversation that explores its roots as a working-class, immigrant neighborhood in the 20th century. As Boyle Heights’ “unofficial historian,” Gonzalez outlines how it became a hub of political organizing in the 1930s—especially notable for the coalitions that developed between different communities. For example, Rose Pesotta, a Russian-Jewish immigrant and anarchist, established a chapter of the International Lady Garment Workers Union in 1932. Noticing that the majority of the seamstresses were Latina, she convinced thousands of them to join—“forever changing the inclusion of people of color in the official union structure in Los Angeles.” Hulsey and Gonzalez discuss the continuity of racist structures of power that have affected the neighborhood, as well as the continuity of resistance movements. In examining why Boyle Heights has become fertile ground for current activism, they suggest that we might look to historical examples in order to create new coalitions and forms of solidarity.

Trinidad Ruiz, a former curator who currently works with Union de Vecinos, speaks about his relationship with the art world in Los Angeles. He was involved in working on Watts House Project, and through the experience, grew disillusioned with the mainstream contemporary art world, turning his focus to community building instead. His work in Watts has helped him in Boyle Heights, where he works for an organization focused on tenants’ rights and housing justice. He contends that one of the main problems with mainstream perceptions of Boyle Heights is that the community lacks its own art and culture when, in fact, there was a thriving local arts scene there before the arrival of mainstream galleries. Ruiz points out that while anti-gentrification groups have targeted galleries and small businesses, they have also gone after local property owners and have put pressure on them to resist increasing rents or flipping their properties and evicting residents. He also calls for putting pressure on local governments: “There needs to be more renter protections—this cannot be a laissez-faire government, it cannot sit on the sidelines.”

Fittingly for L.A., two essays included in this issue focus on mediated representations of the city: Amy Converse discusses the film They Live, in which Los Angeles becomes a kind of pirate utopia—an autonomous zone cut off from the rest of the country. She suggests the possibilities for this image to function as a metaphor in Boyle Heights: “Reimagining contested neighborhoods in L.A. as potential utopias can create radical blueprints for oppressed residents to construct communities in wealthy cultural centers.” She takes issue with the Maoist approach of groups like Defend Boyle Heights that resulted in the repression of artists (and many others), and proposes instead that artists and activists work together with the shared goals of “community control and autonomy,” through reimagined neighborhood councils that represent residents. Here Converse echoes Ultra-red’s emphasis on the important work done by the L.A. Tenants Union, and Ruiz’s work with Union de Vecinos—both of which are made up of artists and non-artists. In their essay, Anastasia Baginski and Chris Malcolm look at how identity is represented in Boyle Heights through an analysis of the L.A. Metro “Guide for Development” of Mariachi Plaza, and the Starz television show Vida, which focuses on the everyday lives of several characters in Boyle Heights. They write that in the show, Chicanx and/or Latinx identity is represented at the expense of a broader class critique. In contrast, anti-gentrification groups have reasserted a class critique along with a problematization of certain forms of identification. They argue that both the planning guide and the television show function through the concept of self-betterment, which “implies the very idea of rehabilitation which the discourse of gentrification relies upon, namely that Boyle Heights and its inhabitants require, ultimately, transformation.”

An East Los Angeles print studio and historic community center, Self Help Graphics & Art was among the group of artists to inform the development of Mariachi Plaza back in the early 1990s. In this issue of FIELD, Executive Director Betty Avila and Communications Consultant Jennifer Cuevas discuss Self Help Graphics’ 46-year history in the community. In the early 1970s, East Los Angeles was entrenched in Chicano Civil Rights activism, producing historical coalitions such as the Brown Berets and the Chicano Moratorium. On August 29, 1970 the Chicano Moratorium organized a march for social justice that ended in tear gas attacks from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s department, taking the life of activist and journalist, Ruben F. Salazar. Self Help Graphics formed in 1973, in the wake of these events, with a mission to foster and uplift “the narrative of the issues of our community by providing access to space, tools, training and capital to support advocacy through artivism, policy change and practicum.”[10] Self Help experienced first-hand the vulnerability of displacement, after being priced out from their former location in the mid 2000s. Now, with the support of city funding, grants and private donors, Self Help has acquired its new location on E. 1st Street in Boyle Heights. As a community arts organization and a stakeholder in city development, Self Help Graphics aims to stake out a different position within the art versus gentrification debate, wherein the outreach, education and dissemination of Latinx art and culture becomes a community praxis for resisting gentrification. In 2016, Self Help Graphics responded to the community’s growing concern over incoming art galleries by hosting the event, “Artist Dialogue about Arts & Gentrification.” Avila notes that the meeting had a focused goal to dialogue with artists, but the nature of the topic brought out a much wider crowd of participants, including The Los Angeles Times and local foundations: “I think it was just — this is an issue that’s impacting so many people and here’s an opportunity to talk about it.” Activist coalitions staged an action to disrupt the dialogue and express their grievances, arguing that the organization had formed ties to “high intensity gentrifiers.”[11] “For us what was really hard to hear,” Avila notes, “was a really pressured group of community members, who are facing eviction, who were not able to pay rent any higher than they currently are, who are really worried and feel attacked and it’s a terrible place to be, and I say that also from the position of a lot of the staff at Self Help who are not able to live in the communities that they grew up in or are experiencing challenges for the same reason.” Avila and Cuevas reflect on this encounter, being held accountable by members of the community, and how the housing crisis informs the organization’s work.

The growing presence of art galleries in Boyle Heights can be seen as a symptom of the city’s booming art market, including large-scale projects such as the launch of an international art fair out of Hollywood, the ambitious expansion of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and its plans for a satellite campus in South Los Angeles.[12] At the same time, the number of people living in the County of Los Angeles without permanent housing is surging, seeing a 12% increase in the last year.[13] With no policy protections for affordable housing covenants in the city of Los Angeles, low-income renters are perpetually vulnerable to displacement when income-restricted housing inevitably turns over to market rate.[14] The tension between low-income residents, artists and art workers in Los Angeles reproduces historical patterns of gentrification in urban spaces: writing about New York City in the late twentieth century, Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan describe the art galleries that gentrified the Lower East Side as a problem of white middle-class cultural production, with similar ties to city-level “renewal” plans: “The representation of the Lower East Side as an ‘adventurous avant-garde setting,’ however, conceals a brutal reality. For the site of this brave new art scene is also a strategic urban arena where the city, financed by big capital, wages its war of position against an impoverished and increasingly isolated local population.”[15] In their analysis, the authors argue that artists and art workers must confront not only the footprint of art development on working class communities, but also the political power of aesthetic representations for perpetuating inequity. Deutsche and Ryan described this instrumentalization of art, writing that “gentrification is aided and abetted by an ‘artistic’ process whereby poverty and homelessness are served up for aesthetic pleasure.”[16] In this way, the layered tension between artists, art workers and working-class communities of color is also reminiscent of the contradictions inherent to avant-garde art, a longstanding conversation within art history.[17] The point of convergence between art and gentrification currently unfolding in Boyle Heights has broad resonance for artists, art workers and the field of art history, which must contend with the role of art and aesthetics in affecting the neo-liberalization of urban space, and in producing successful counter-movements for social justice.

Erika Barbosa is a member of FIELD‘s editorial collective. She is a PhD student in the art practice program at University of California, San Diego.

Noni Brynjolson is a member of FIELD’s editorial collective. She completed her PhD in Art History, Theory & Criticism at the University of California, San Diego in 2019, and is currently an Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Indianapolis.

Notes:

[1] See Boyle Heights Property Ownership, Displacement, and Recommendation Report: Understanding the Needs of a Neighborhood at a Crossroads. LURN Network. April 2018. https://lurnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/FinalReport_LURN_V2.pdf [Accessed Sept 26, 2019] [LURN Network is now Inclusive Action For the City: https://www.inclusiveaction.org/]

[2] An interstate highway was built directly on top of Hollenbeck park, one of the neighborhood’s few green spaces, followed by the construction of the world’s busiest highway overpass, enclosing Boyle Heights by five intersecting highways. These projects have led to high risks of asthma in children, among other air pollution related concerns. See: Jasmin Mara-Lòpez, “Los Angeles neighborhood bears the brunt of air pollution” USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. August 25, 2011: https://www.centerforhealthjournalism.org/fellowships/projects/los-angeles-neighborhood-bears-brunt-air-pollution [Accessed Sept 26, 2019]

[3] Cultural Needs Assessment: Metro Red Line East Side Extension Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. February, 1995. Metro Archives, (p 7): http://libraryarchives.metro.net/DPGTL/eirs/GoldLine_Eastside/1995_cultural_needs_assessment.pdf [Accessed Sept 26, 2019]

[4] James Rojas, “Looking for the Rasquache at Mariachi Plaza in Boyle Heights.” KCET History & Society. January 29, 2015. https://www.kcet.org/history-society/looking-for-the-rasquache-at-mariachi-plaza-in-boyle-heights [accessed Sept 26, 2019]

[5] Defend Boyle Heights, @DefendBoyleHts. “For over seven months, DBH has had intense internal conflicts that stagnated our work. This reconstitution isn’t a loss – it’s us actively fighting that stagnation! We will no longer have unprincipled unity which holds all of our orgs & DBH back!” 2 December 2018, 4:14 p.m. Tweet.

[6] In a 2016 article in the Los Angeles Times, Leonardo Vilchis is quoted as saying: “The only way we are heard is when you say no. And that’s terrifying because you’re a jerk who says no. But we have had more negotiations now since we’ve said no than if we had said yes.” In Carolina A. Miranda, “‘Out!’ Boyle Heights activists say white art elites are ruining the neighborhood…but it’s complicated,” Los Angeles Times, 14 October 2016.

[7] Defend Boyle Heights, “A community betrayed: How Self-Help Graphics & Art actively supports gentrification,” 26 October 2018, http://defendboyleheights.blogspot.com/2018/10/a-community-betrayed-how-self-help.html?q=%22art%22. Accessed 25 September 2019.

[8] See Boyle Heights Alianza Anti Artwashing Y Desplazamiento’s public statement, “The Short History Of A Long Struggle,” [Accessed 09/26/19] http://alianzacontraartwashing.org/en/coalition-statements/bhaaad-the-short-history-of-a-long-struggle/

[9] In the Draft Boyle Heights Community Plan published in October of 2017, [Land Use] Goal 12 states, “Boyle Heights, particularly the industrial district along the Los Angeles River, is a desirable place for innovative industries to locate.” (p 22) https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B5vZFy05DiQGbjhIbDBjX2dBOUU/view

[10] See Self Help Graphics’ statement, Advocacy, Cultural Preservation and Anti-Displacement Efforts. https://www.selfhelpgraphics.com/cultural-preservation-gentrification [Accessed Sept 26, 2019]

[11] Throughout their literature, Defend Boyle Heights and Boyle Heights Alianza Anti Artwashing Y Desplazamiento both use this term to capture the degree of power held by certain entities contributing to gentrification in the neighborhood.

[12] LACMA director Michael Govan announced a potential plan to add up to five satellite campuses to LACMA’s current sites. The first proposed site being an 80,000-square-foot industrial building in South Los Angeles Wetlands Park. With multiple news outlets covering the projected plans, see The Los Angeles Times editorial from July 16, 2018, “Take LACMA and put it in South L.A.?”; Jori Finkel writing for The New York Times, January 24, 2018, “Lacma Seeks to Expand Its Footprint Into South Los Angeles.”

[13] This 2019 data was reported by several news sources including Anna Scott, “Despite increased spending, Homelessness Up 12% in Los Angeles County,” NPR, June 4, 2019.

[14] Jenna Chandler covers affordable housing covenants in the June 25, 2019 article, “The big problem with affordable housing” for Curbed Los Angeles.

[15] Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan, “The Fine Art of Gentrification,” October, Vol. 31 (Winter, 1984): p. 93.

[16] Ibid., p. 111.

[17] Peter Bürger offers a succinct overview of the notion of contradiction as it occurs in analysis of the historical avant-garde. See Peter Bürger, Bettina Brandt, and Daniel Purdy, “Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt to Answer Certain Critics of ‘Theory of the Avant-Garde’.” New Literary History 41, no. 4 (2010): 695-715. “Whereas a nonspecific concept of the avant-garde marks, above all, a point in the continuum of time, in other words, the Now, designating the newest art of modernity, “Theory of the Avant-Garde” attempts to provide a clear differentiation between two concepts, without thereby creating an abstract opposition between them. In so far as the historical avant-garde movements respond to the developmental stage of autonomous art epitomized by aestheticism, they are part of modernism; in so far as they call the institution of art into question, they constitute a break with modernism. The history of the avant-gardes, each with its own special historical conditions, arises out of this contradiction.”