Art of Resistance: An Interview with Zhanna Kadyrova on Ukrainian Art during the Russian War

Valeria Radkevych

In the winter of 2013-2014, Ukraine was fighting for its democratic future against President Yanukovich’s attempts to turn it into a police state, suppressing any public expression of protest. This fundamental right has been denied to the people of Ukraine for way too long, first by the Russian Empire, then by the Soviet Union. Although the Revolution of Dignity reached its goal, depriving the treacherous President of his seat, it left the country vulnerable and exposed. Russia did not hesitate to take advantage of the vacuum and held a series of illegal referendums in Crimea and Donbas, which were later classified as a military invasion since the Russian military overlooked the process. In other words, it was in the Spring of 2014 that Russia invaded Ukraine for the first time.[1] Suddenly, it was not just us Ukrainians anymore: the foreign presence in the small provincial communities was very palpable, even if the invader was making every effort to disguise it. It felt like a home invasion, where the intruder pretends to be an extended family member.

The very concept of war seemed very outdated at the time. When someone said “war,” they would normally refer to the Second World War. It changed in 2014. Now the word “war” meant the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the deportation of Crimean Tatars, the loss of our family home in Luhansk, and an infuriating amount of propaganda, whose main statements blamed the Ukrainian state for firing missiles at its own towns and brutally suppressing a Russian-speaking population, just to name a few. As a family from Luhansk, we took everything especially painfully, because these lies were so evident to us. Perhaps the most surreal part of it was having to convince the rest of the world that the Ukrainian border was, indeed, violated by a foreign military. A solid wall of lies and decades of whitewashing supported the Russian plan of remaining unnoticed in their invasion and promoting the story that 2014 was about the presumed “civil war” in Ukraine.[1] Unfortunately, the plan was successful, because today, when one refers to the “Russian invasion of Ukraine,” they usually have in mind February 24, 2022.

The events of the Revolution of Dignity shook the Ukrainian community to the core and marked the beginning of a transformation of the collective identity. However, the occupied land and the frontline were limited to parts of the Donbas region and Crimea, and the rest of the country continued living their day-to-day life untouched by war. Artistic practice, on the other hand, followed the sensibility of certain artists, and war was subtly making its way into their body of work. Whether the occupation of Crimea and Donbas affected the artists directly or indirectly, they perceived its influence on society, governmental policies, institutions, and media. While the shock brought by the bloody Revolution was momentaneous — a sudden splash of emotions upon the realization that freedom was something we still had to fight for — the war was there to stay, and thus had to be analyzed thoroughly.

Those who grew up or went to art academies during the Soviet rule, when socialist realism was the only acceptable method of artistic representation, reflected on this ideological legacy and its influence on modern-day Ukraine. This rumination was not new to the national art scene, as it was one of the main themes of the post-Soviet artistic community in the years following the fall of the Soviet Union. However, since the beginning of the 2000s and especially after 2014, it was a younger generation that joined the age-old discourse, fuelled by the invasion of their country.

A powerful instance is Nikita Kadan’s installation The Possessed Can Witness in Court (2015). Here, a series of objects is placed on shelves that recall a museum or an archive. Some of the objects are taken from the collection of the National Museum of History of Ukraine (coming from Crimea and Donbas region), and others are created by the artist himself, such as the neon outline of the occupied Crimean Peninsula. The objects that once formed an ideological narrative of the Soviet Union and its semi-fictional system of knowledge are now presented as empty shells, forging doubts about the conventional history. The living plant inside the installation not only hints at the element of cure and preservation but also signifies institutional compliance with the state-approved politics of memory. Since the plant is alive and well, someone must be taking care of it. This human presence indicates that the objects are not a mere archive of forgotten symbols, but a well-kept museum that allows the fabricated history inside its walls. Nikita Kadan, of course, was not alone: Artists like Pavlo Makov, Alevtina Kakhidze, Vlada Ralko, and Zhanna Kadyrova all reflected on the new reality Ukraine was facing.

Kadan’s work provides an important institutional critique: Most Ukrainian cultural institutions are still adherent to the Soviet ideological framework of knowledge and storytelling, and it is time to start changing. The beginning of the war makes it clear: the decolonization of minds is a necessary condition for freedom in Ukraine since certain pre-set notions of culture and history are complicit in the diffusion of Russian propaganda that now poses an existential threat to the country. For instance, in the imperial system of knowledge, Ukrainian culture has been dismissed as profoundly provincial, naive, reactionary, and rudimentary. Soviet cultural policy insists on the former’s inferiority through the display of its “exotic” costume tradition, language, folk rites, and art that remained tied to the village and the outskirts and did not have a place in a civilized and progressive city. This feeling of inferiority, that one only belongs to an assigned place of a “younger brother” (a metaphor commonly used during Russia’s interventions into Ukraine’s internal affairs), greatly influenced Ukrainians, who struggle to associate themselves with their own country and culture.

Institutions do not manage themselves, as their politics depend on the people who are in charge, on their history and mindset. Understandably, a person from Soviet Ukraine who grew up and has built a career within the imperial coordinates will pave the same path in their institution. This is one major reason why Ukrainian museums overlooked contemporary art and even modernism or the historical avant-garde that developed on their territory. Russia’s appropriation of Ukraine’s cultural and artistic heritage played a big role in it as well. Such names as Alexandra Ekster, Sonia Delaunay, Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzky, or even Kazimir Malevich were not associated with Ukrainian culture even in Ukraine. On the other hand, Ukrainian museums would hold loud exhibitions of foreign artists or fashion houses, like the Chloe exhibition in 2019.[2] It was an informed choice because the museum-going audience was not quite ready for a dialogue with contemporary art. It seemed that the artists and their audience existed in two different dimensions that did not share history or existential challenges. Perhaps this separation was caused as the two groups tended to visit different spaces: while the wider public was attracted by conventional museums with the Soviet-era aura, the contemporary art-scene lived in galleries, independent art spaces, or private apartments. Artists also did not share the same day-to-day routine and problems with their potential audience.

However, as the Russian military machines started gathering along the Ukrainian border and the tensions increased, the culture began looking inward more often. For instance, from September to November 2021, the National Art Museum of Ukraine presented the exhibition “Father, the Helmet is Tight,” the first retrospective of Ukrainian art of the Independence in this major institution. Finally, the path of the contemporary artistic community crosses the one of the regular museum-goer. In the face of imminent danger, Ukraine turned to look at its roots, holding on to the heritage of its quest for freedom.[3] Art increasingly became a necessity for building a dialogue about Ukraine’s contemporary history, its cultural identity, and its place on the international contemporary art scene, and less of an accessory for a few, providing a perspective on the reality they lived in in an unconventional, critical way, with a hint of dark satire.

Further cultural shift happened with the beginning of the full-scale military invasion that Russia launched against Ukraine in February 2022. The air raid alarms started waking Ukrainians up across the entire territory of the country, not just in Crimea and Donbas. The imminent danger of war, the necessity to escape the missiles, and the search for existential reasons were now among the conditions of physical and spiritual survival for both the individuals and the collective. The national war became a common denominator for artists and their audiences. On one side, the creative community had to deal with the same emergency as everyone else, which was reflected in their artistic practice. On the other side, for both the artists and their audience, their day-to-day problems finally aligned. It is as if suddenly someone gave the public a key to interpreting contemporary art and conducting a dialogue with artists. In other words, art became comprehensible when it began scrutinizing a common struggle of war. The crowds that once flooded the museums for the exhibition of foreign authors were now there for collective exhibitions of Ukrainian contemporary art.

After a brief pause in the months following the full-scale invasion, the National Museum of Arts of Ukraine carefully opened its doors to visitors for lectures and conversations about art and colonization, cultural heritage, and institutional influence. Events and exhibitions held in that period had a therapeutic effect on both the organizers and the visitors, as they gave people time for distraction and reconnection between missile attacks. Moreover, facing an imminent threat to its existence, the nation started looking for more markers of self-identification, often discovering them in its art and culture. Artists noticed a growing interest in their art as well.

One of the most visible artists of the contemporary Ukrainian art scene, Pavlo Makov, represented Ukraine at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. The Russian invasion caught the Ukrainian delegation in the middle of the preparation process. Makov’s installation, Fountain of Exhaustion, which opened months after the invasion, placed the artist in the international spotlight. It gave him a loudspeaker, which he used to talk about the war Russia was waging on his country. Even Ukrainians who were barely interested in contemporary art or knew very little about it could see how the artistic presence of the country on an international platform like the Venice Biennial could transmit the voice of a nation and raise awareness about the atrocious war.

Ultimately, art events become the recreation communities in different Ukrainian cities are all eager for. The exhibitions became sites for connection, dialogue, and distraction. In one of his interviews, speaking about his exhibition in Kharkiv, Makov noticed:

“At the opening, I was moved to tears—never before, at any opening, had I seen so many people, from young to old, as I did under shelling in Kharkiv. I understand that this is not about me, that this is not just an artistic event but a social one. And it is very important that all these people came.” [4]

This interview with Zhanna Kadyrova reveals a similar sentiment. An internationally acclaimed artist, Kadyrova has been touring the world for years. While she admits that Ukraine’s international presence is paramount, her primary goal after each trip is to return home to Ukraine and Ukrainians.

It is hard to track Zhanna Kadyrova down for a chat. She is currently one of the busiest (and the most seen) Ukrainian artists on the art scene. Represented by an Italian Galleria Continua, she opens one show after another. Below is a conversation about the nature of her art, and especially about the way her art intertwined with her personal experience of war, which transformed it into a comprehensive window on the devastation and atrocity of wartime.

VALERIA RADKEVYCH

Your research stretches across white cube gallery pieces and public art, and you excel in both. I see both satire and sensibility in your art, and this remarkable intuition of yours reflects reality in an incredible way. It makes you one of the most well-known Ukrainian artists across the art world. This takes an enormous amount of work, and in fact, you are always busy. I would like to access the ways your practice and research changed over the past 10 years, since the beginning of the war in 2014.

ZHANNA KADYROVA

I think I have a good example of such a change in one particular artwork. I made similar works that recall the map of Ukraine with the broken Crimea peninsula lying next to it [Untitled, 2014, 2022 – author]. A brick wall burnt black from one side and featuring the wallpaper from the other side. Taking this work as an example, you can trace a clear change, like a story that continues. I made the first version of it in the beginning of the war, in 2014, and the map was missing its Eastern part and Crimea. The second one is now in Prague as part of the biggest personal exhibition I have had in my career. For this version of the brick map, I also gathered some artefacts, such as fragments of dishes, windows, melted bottles, and a variety of burnt household objects from the villages in the Donetsk region. So, it looks like a new version of the artwork, which appeared 8 years after the first one.

As long as the war was not reaching Kyiv, I continued some of the practices I had started before. In most of my works, I focus on site-specific art. I really like to work on-site, discovering some local stories and creating something together with local people or from materials that I found. That is what interests me the most. Of course, there are some objects or photographs, so I don’t have any stable, unified technique. I work constantly, choosing what suits the concept best. The media is secondary.

VALERIA

I know that after February, 2022 your work took a dramatic turn and got on a very defined, very personal path.

ZHANNA

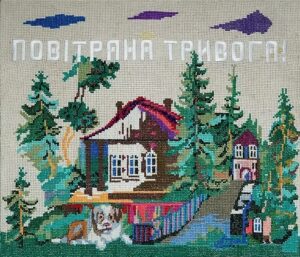

With the outbreak of the full-scale war, my focus completely changed. And since February 2022, I have been working exclusively with timely Ukrainian situations based on my experience. I was also an internally displaced person: for the first three months, I left Ukraine, then I lived in Transcarpathia. There, I created pieces I couldn’t have come up with in Kyiv. Like the project Palianytsia. River stones that I found directly on the riverbank, in the village where I lived. And the pieces from the series Anxiety are traditional tapestries that decorate rural houses. Most of them have no author. They are folk art. I bought them from different collectors, flea markets, online auctions, and added the inscription ‘Air Alert’ to them, which, as it were, destroyed the very meaning and plot of the image, because usually the tapestries represent something very sweet, peaceful, and cozy, associated with children, with animals, with cottages. Such an idyllic scene. The text on this handmade work, printed with a typewriter, destroys the meaning of this picture, just as the war destroys our lives. These artworks appeared in Transcarpathia, because in Kyiv, I would not have seen any stones or embroidered tapestries. In fact, there are many such pieces and I continue to work. All the projects that were planned, but are not related to the situation in Ukraine, are on hold and waiting for me to be free. And the time will come only when the war is over. Right now, I am fully focused on telling stories through art, sharing information and my experience of living in Ukraine.

VALERIA

In one of your interviews with Suspilne, the journalist asked you this question, which seemed naive to me at first. “Is art capable of changing the world?” And then you told her that you gave all your profits to volunteers or directly to the army, and that this was an obvious benefit of art, which helped the soldiers who defended us directly. But does art change not just the material part of the world, but the moral part of it, the emotional part of it? Is art able to change people’s opinions about events, to make people more sensitive? How do you think it works, and does it even work?

ZHANNA

In fact, my opinion in this regard has changed drastically since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. I was very disappointed with my choice of profession at the time because when we faced the reality of war, everything seemed very weak and ineffective in comparison. It was frustrating to think about 20 years spent on something that could not change anything at all.

Then, little by little, I started gaining financial profits and donated them. I mostly tried to support the military, those who had been musicians, artists, and workers from the cultural industry before the war, and there were a lot of them. Quite a few became volunteers and worked with foundations. My first trip abroad, in April 2022, was to open the first Palianytsia, and then the second exhibition was in Venice. Galleria Continua arranged a small space for me in Venice. It was organized in haste, very quickly. It took three weeks. We opened this exhibition, and a lot of people saw it and started inviting me to showcase my work. Now there have been 50 exhibitions of Palianytsia in different countries and cities. The project has already been presented 50 times. The pieces are present in museum collections, in the Bundestag, for instance. This is not an ordinary project. This is a humanitarian project, first and foremost. And by acquiring this work, people declare their support for Ukraine with their money, which, in my opinion, is better than with words.

I still receive a lot of feedback, because there are so many exhibitions. Once, a woman came up to me after watching the film about the artwork, and she said that she had never felt so close to Ukraine as she did after that event. In Sweden, I met this lady who had emigrated with her family from Prague after the Russian military entered the city. She hugged me and said, “I remember the blood on the streets.” She said she was empathizing with us a lot. I think that after 2.5 years of war, everyone is tired of this news, and a lot of media channels are ignoring the Ukrainian agenda. And this is exactly what the language of art is capable of, as it does not work with some literal news templates. If this art is well-made, it touches and immerses you in the issues.

VALERIA

It is remarkable how the artwork causing an international resonance was originally created in a remote village in the middle of the Carpathian Mountains. The authenticity of it can hardly leave anyone indifferent. What was your experience in the village like, though? Were the locals curious about your work?

ZHANNA

My partner and I started organizing exhibitions for the local community, in the house where we lived. It was a small village where people were very far from contemporary art. We even had film screenings there. And a 90-year-old lady said that she had never been to a cinema. She was thrilled to see us just showing films on the wall with a projector. The continuity of cultural life, or the succession of artists, is the key to healthy development. Even in such difficult conditions, we continue to create and cultivate culture among people. Professionals or not, it doesn’t matter. If we don’t know how to do anything else, we must do what we know best.

VALERIA

Art as an element that unites the community around curiosity and shared values. It is very touching. It must be quite rewarding for the author. Frankly, war is full of frustration and helplessness, but it looks like you found a key to defy it.

ZHANNA

On May 19, we opened an exhibition in Zaporizhzhia. This was the same set of 2022-2024 artwork, with embroidery, a rocket 2, and graphics from the Diary series. I said that Palianytsia has opened 50 times in different cities, and I have been present at many opening nights, but I have never had such an emotional one. I was just overwhelmed with feelings. Firstly, my friend who fought in the Zaporizhzhia direction came. He sponsored our festival from the first day of the war, and he himself came from Lviv. He didn’t notify us. He just came. Another friend I just met on the street came beforehand, who is from Kyiv, had a short time off duty and a date with his wife, and he came to that exhibition, too. The mayor of Zaporizhzhia was also present, as well as the governor, museum workers, and a whole bunch of people. I could see this thirst. They looked at me as if I were a Messiah. On the one hand, it was very intimidating but on the other hand, I understood how much people need culture. People had lived all their lives in a huge city of almost a million inhabitants. After the war started, many of them left, but their habits of having some kind of cultural program – going to the theatre, attending exhibitions and concerts – did not disappear. But nobody is bringing any cultural events here right now. Yes, this is a city that is 30 km from the frontline, but it declares that it lives a normal life, so we must help. And now, while I have time, I want to concentrate on bringing my work to people there and in other Ukrainian cities. Because when you work abroad, you spend your time explaining everything from the beginning, which is quite difficult. But here you don’t have to explain anything. It does not even matter what you bring, but the very fact that you did it. You made this gesture towards the cultural community. They can see it in real life. They don’t have to go to Kyiv to see an exhibition of contemporary art by a Ukrainian artist. Here we show that we are together and continue to live, fight, and make art.

After this discovery, my opinion changed about what you call the power of art. It is about supporting each other. This discovery touched me very profoundly and charged me a lot. And now I really understand what I want to do next. Many people continue to live in the places where they lived before the war, even though it is dangerous, and that life there is completely different now. We even agreed with one of the employees of the Zaporizhzhia museum that I would leave one Palianytsia piece in the museum’s collection. We’ll see what happens next, but here the function of art is not about monetary gain. It is not even about helping the military, but civilians, people of culture who want to live in their city. It is a gesture of solidarity, that we are together, that we are Ukraine. The issues I raise are close to everyone here. In Zaporizhzhia, there is no need to explain what an air raid is. Here it goes off at least five times per day.

VALERIA

Yes, about the air raid. I was very impressed by the Data Extraction project you started in 2012. You’ve been focusing on the urban landscape, and your sensitivity to it is extraordinary. You extracted pieces of damaged concrete from the streets and hung them on the gallery walls. And those pieces of concrete are recognizable to the ones who walk on it every day, and the landmine damage adds a strikingly eerie detail to these familiar landscapes. Can you tell me more about it?

ZHANNA

Yes. These are pieces of asphalt taken in Irpin in a new residential area, from the parking lot near the ATB supermarket. They contain traces of landmines that were sprinkled over the area where civilians live. The name “Data Extraction” means information retrieval. This piece of the road is an artefact, since everything has been repaired long ago, the roads, the parks. The houses were demolished and rebuilt because they could not be fixed. When I was there last time, there were dozens of units of equipment that were being installed in the neighborhood with private houses, to fix the road. But the reparation mostly concerns the Kyiv region – the exemplary cities that everyone has heard about: Irpin, Bucha. But a little further away, in Moshchun, people live in tiny modular houses that they were given on the ruins of their homes.

VALERIA

I feel like this is a story about recovery. But the wound cannot be healed while it is being inflicted repeatedly. That is, the missiles are raining down on Ukrainian cities every day, wiping out entire towns and neighborhoods.

ZHANNA

My friends, volunteers from the Left Bank Foundation, have been working in the Kharkiv region for a long time, repairing roofs. They repaired hundreds of roofs. After the last breakthrough of Russian troops, the town where they worked was forcibly evacuated. Unfortunately, this momentary recovery, when the front is unstable, is useless. But we must hope for the best. And of course, people do not want to see those burned-out buildings and holes in the asphalt. That’s why the local administration is trying to patch everything up as soon as possible. The artworks from the Data Extraction series are valuable because there are no such roads in Irpin anymore. This is a real artefact, evidence of a war crime – the shelling of civilian residential areas. This work, in addition to being formally interesting, has the value of material evidence. Yes, I started with a different issue. I first talked about corruption when I started cutting out those parts of asphalt as evidence of the misuse of money. We removed several pieces of asphalt on the Calabria motorway in Italy; it was already of poor quality when it was first laid. But no one was going to stop the poor-quality construction because of corruption. And when I saw those traces in Irpin, I continued that project I started in Italy.

VALERIA

It is even more impressive to see these pieces inside a sterile white cube, with the pristine wall looking through the hole left by a piece of sharp, hot fragment of a missile.

ZHANNA

It also references the classical structure of the art world. When you hang proof of violence up on a gallery wall, you immediately draw a line between the culture that evolves throughout thousands of years and the war that burns everything to the ground. And these two opposite things exist side-by-side and at the same time in the world. I would like to draw attention to this conflict.

VALERIA

Most of your work involves the public dimension in one way or another, while also expressing some intimate reflection coming both from you and from your audience. It is clear that these pieces touch people profoundly, but how exactly do you involve the viewer in your production?

ZHANNA

In 2007, I made Monument to a New Monument. In 2009, it was installed in Sharhorod [a town in Vinnytsia region – author]. It is a reflection on how one hero, in time, substitutes the previous one. Some heroes are taken down, and others are put on pedestals. And so, I created a monument to a monument – a universal pedestal where everyone can imagine their own hero. It represents the moment when it’s still covered, and you don’t see the face of whoever is there.

It captures the moment of inauguration, and it doesn’t need to be demolished because it’s new. When I unveiled it in Shargorod in 2009, people came up to me and asked, “What is this, wouldn’t it be better to put Kotsiubynskyi for us?” And I said, “Yes, this is Kotsiubynskyi.” Then a woman came up to me and asked, “Could you make a monument to my son who died?” This was before the war. I said, “Yes, you can let it be a monument to your son.” When I came there later, I was told that it was a monument to the Virgin Mary. They said that someone had some kind of apparition there, and so now it was tied to it. Well, the life of a sculpture in a public space is like that. To be honest, I am glad that there is such a mythology around the monument.

VALERIA

In fact, it is curious how the apparent neutrality of art is influenced by the customs and traditions rooted in the territory. It develops various layers of meaning over time. Coming back to your current practice. Palianytsia, for instance, is a curious project starting with the title itself. We used to laugh about how this word is unpronounceable for Russians, and with the full-scale invasion, our jokes became the reality, when we needed to spot the saboteurs who would spy on our military positions, using “palianytsia” as a password. And just like the case with the monument, now it is not just any loaf of bread, but a sacred tradition for Ukrainians, something that represents us.

ZHANNA

I like leaving room for interpretation because everyone experiences art in a different way. “Palianytsia” is a word that serves as a sign of friend or foe, and that is why it was the starting point for the title of the artwork. In our tradition, a guest is greeted with a freshly baked loaf. However, this work is not a welcome bread, but the bread for the occupant. And the meaning of “Palianytsia” changed again when the Russians started exporting our bread and stealing our grain from the occupied territories. Then again, some people brought up religious connotations. When Jesus entered Jerusalem, some people praised him, while others deemed him an impostor. And at that moment, Jesus said to his supporters that if they suddenly fell silent, the stones would start shouting. And I was told that my stone was the shouting stone described in the Bible. It’s powerful, and I cannot help but be happy that the work provokes such a difference of opinion among people. I have to admit that this work was created in a terrible emotional state.

VALERIA

Does art help you elaborate on the trauma?

ZHANNA

Definitely. It is nice to have some distraction from the grim thoughts while working on pieces.

The Ukrainian Pavilion at Venice Biennial 2026 will see Zhanna Kadyrova’s project take over the space. Entitled “Security Guarantees,” it is a witty reference to both the current attempts to find a resolution to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a chain of historical decisions that brought us to this point. I went back to chatting with Zhanna about her upcoming project to find out what it is all about.

VALERIA

Zhanna, in 2026, you will represent Ukraine at the Venice Biennale with the project Security Guarantees. At its center is a sculpture that was physically evacuated from the front-line city of Pokrovsk [in Donetsk region]. What significance does this object carry, given its complex biography? And what exactly will the public encounter in the Ukrainian Pavilion?

ZHANNA

We are planning to bring the actual sculpture that was evacuated from Pokrovsk and present it within the Pavilion. Alongside it, we will show a documentary film that captures the evacuation process. We also plan to shoot a new film during the journey to Venice, documenting the sculpture’s movement and transformation en route. The installation will also include factual and archival materials: information on what was built, when, and under what circumstances, as well as data on the current state of the city. We are also considering using DeepState maps to contextualize the geographical and military reality of the region.

The central piece is “Deer,” a concrete sculpture originally conceived as a permanent installation in a public park in Pokrovsk, on the site of a dismantled Soviet jet, which is itself a former symbol of militarized power. The sculpture was never intended to move. But now, due to the war, it has been displaced. It is homeless, without its pedestal, and that rupture lies at the heart of the project.

Some curatorial decisions remain open. We will conduct a site visit in Venice and assess the architectural and spatial proportions of the venue, and only then will we finalize the exhibition’s form.

VALERIA

The title “Security Guarantees” clearly resonates with Ukraine’s recent history, both immediate and long-term. Does the project explicitly address not only the ongoing war but also earlier historical shifts?

ZHANNA

Absolutely. The year 2026 marks exactly thirty years since Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal, the third largest in the world at the time. I believe that this is deeply symbolic. The sculpture was placed where a Soviet military aircraft once stood. That jet represented a kind of hard power. The substitution of that object with a peaceful, geometric form reflected a shift: away from the militarized Soviet legacy and toward a European and cultural path of development.

And yet, what do we have today? A sculpture meant to remain in place has been uprooted and now drifts across borders without a fixed home. It is a potent metaphor: for dislocation, for the fragility of memory, and for the consequences of relying on guarantees that prove unreliable in practice.

In that sense, I believe the project is timely, precise, and painfully relevant. We are once again discussing security guarantees, the terms under which this war might end. I’m grateful to the selection committee for recognizing how closely this proposal reflects Ukraine’s current condition.

Zhanna Kadyrova was born in 1981 in Brovary, in the Kyiv region, Ukraine, where she currently lives. After graduating from the Taras Shevchenko State Art School in 1999, she received the Kazimir Malevich Artist Award and the Grand Prix of the Kyiv Sculpture Project in 2012. She was awarded the Special Prize (2011), Main Prize (2013), and Special Prize – Future Generation International (2014) by PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv (Ukraine). She was also previously a member of the “R.E.P.” group (Revolution Experimental Space).

Kadyrova’s practice, tackling since its very beginning disciplines as different as sculpture, photo, video, performance, focuses on the exhibition site and space. In her work, the issue of context unravels to reveal the rhythm of History on the move – that of a world whose multiple layers disappear behind their immediacy. Often challenging the aesthetic canons of the socialist ideal still present in contemporary Ukraine, Kadyrova’s perspective is partially informed by the plastic and symbolic values of urban building materials, including ceramics, glass, stone, and concrete.

Kadyrova was developing several site-specific projects in Ukraine and beyond until Russia’s invasion in February 2022 abruptly halted her plans. After relocating to the Carpathian Mountains, she began working on the humanitarian project PALIANYTSIA, which has already been exhibited worldwide (Italy, Germany, Norway, Japan, France, the US, Sweden, Austria, Georgia, Romania, Thailand, India). Kadyrova is now back in Kiev and produced new works about war, which were featured in her first major retrospective at the Kunstverein Hannover (Germany). Another major exhibition, “Flying Trajectories,” opened at the PinchukArtCentre in June 2023. In addition, she takes part in the show “From Ukraine: Dare to Dream,” curated by the PinchukArt Centre as a Collateral Event of the 60th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia.

Kadyrova participated in numerous biennials, including the 2023 Kochi Biennale, the 3rd Bangkok Biennale (2022), the 58th, 56th, and 55th Venice Biennale, the 2017 Kyiv Biennale, and the 33rd Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, Slovenia. During the past years, she focused on site-specific projects, including an outdoor installation in the Semmering Mountains (Austria), a spread intervention and permanent sculpture in the village of Tolfa (Italy), and a sculptural project for the Shanghai Jing’an International Sculpture Project (JISP) in Shanghai (China). (From Galleria Continua)

Valeria Radkevych was born in 1995 in Luhansk (Donbas region, Ukraine). She is an independent curator, writer, and art historian with an MA in Visual Arts from the University of Bologna and Paris 1 – Pantheon Sorbonne. Her field of study is the interconnection between art and politics.

Notes

- Umland, Andreas, and Jakob Hedenskog. 2024. “Why the Donbas War Was Never “Civil” – SCEEUS.” Sceeus. https://sceeus.se/en/publications/why-the-donbas-war-was-never-civil/.

- “Vintage Dresses From Chloé in a New Exhibition at NAMU.” 2019. The Village Україна. March 7, 2019. https://www.village.com.ua/village/culture/culture-news/282627-yak-chlo-vplinuv-na-istoriyu-modi-u-namu-vidkriyut-novu-vistavku-pro-brend.

- Білаш, Ксенія. 2022. “NAMU Opens A Contemporary Art Exhibition Encompassing Thirty Years Of Independence.” Ua, March 10, 2022. https://lb.ua/culture/2021/09/06/493338_namu_vidkrivaie_vistavku_suchasnogo.html.

- Білаш, Ксенія. 2024. “Pavlo Makov: “Prove Our Cultural Identity To The World, Not Only With Prymachenko But Also With Contemporaries».” Ua, June 8, 2024. https://lb.ua/culture/2024/06/07/617214_pavlo_makov_dovoditi_svitu.html.