Editorial | Spring 2025

On the Occasion of our Tenth Anniversary

Welcome to the tenth anniversary issue of FIELD. It’s hard to believe that a decade has passed since we first launched our modest editorial enterprise. Then, as now, our primary goal is to provide an accessible platform for independent critical writing on a range of socially engaged art practices. These terms require some explanation. While we do publish essays by artists writing about their own work, our primary goal is to support analyses developed by critics who are not directly involved with the creation a given project. These analyses require, of course, a deep immersion in the practical unfolding of a work, but they also entail a degree of independence, an ability to see and consider aspects of the work that may not be available to the practitioner. That condition of adjacency, of relative or partial independence, is important because some of the most productive insights are generated dialogically, at the boundary between the self and the other, between distance and intimacy. Practice itself, of course, throws up its own invaluable insights, but there is never a direct, unmediated access to the truth of a work; there are always multiple truths, multiple trajectories of meaning to be unfolded. The term “social engagement” requires its own qualification. It suffers, of course, from a certain parochialism, as is the case with almost every other term one might use to describe the disparate body of work we consider. For better or worse, it has remained central for us, even as our interests as a publication extend far beyond the geopolitical context in which this terminology first evolved. All art, of course, is “social,” no matter how esoteric, insular or recursive, it makes an appeal to a potential viewer; it holds out the hope, at the very least, for someone to receive it, to take it in, to be moved by it or to respond to it. What differentiates socially engaged art is the deliberate decision to extend this social and dialogical dimension within a larger network, beyond the privatized encounter between a physical object or text and an individual viewer or reader (an encounter that historically evolved, of course, in conjunction with the expansion of a bourgeois public sphere and its affiliated cultural institutions).

For our purposes this is evident in the work of hundreds of artists and art collectives over the past several decades, who have chosen to operate beyond the ideological and institutional confines of the mainstream art world. The art world, of course, is not a monolith; there are fissures, liminal zones and points of contact between the class enclave of the “art world” and the broader world of cultural and political life that is intelligible to a larger public. And just as there is an art world of well-heeled celebrities, globe-trotting curators, artists and collectors, art fairs, museum boards and auction houses, there is also an art world, less visible, less celebrated, that exists on its periphery. The limitations of the haute artworld are evident in the ease and rapidity with which museums have chosen to subordinate themselves to the diktats of the current administration. A recent example of this can be found in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s attacks on its famed “Independent Study Program” (ISP), including the censorship of an ISP performance work that expressed support for the Palestinian people, the resulting dismissal of the Associate Director of the ISP, and the suspension of admissions to the program (all clearly intended to bring a recalcitrant ISP under the direct control of the museum’s director, board and curatorial staff).1 This is a telling example, as the ISP is hardly a hotbed of insurrection. Rather, it has functioned for decades as a reliable tracking mechanism for conventional art world careers. And yet, even the modest gesture of contesting the genocide in Gaza was too much for the museum’s director and board to countenance.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. An art world that is, at the end of the day, dependent for its survival on the political commitments of extremely wealthy people will never sustain forms of practice that pose any meaningful risk to the reputation or well-being of this same donor class. This is a world that can absorb, and monetize, an endless number of formally encoded and radically interiorized critiques (so long as they never deeply probe the materialist underpinnings of the art world itself), but which balks at expressing the most basic forms of human conscience and solidarity with the widespread suffering in Palestine. The rise of neo-fascism under Donald Trump is vindication, if any were needed, that a broad cross section of the very wealthy in the U.S., at least, will happily endorse the most extreme forms of repression, so long as they and their families can benefit financially. For our purposes, then, the most authentically critical work is not produced within the wealth nexus of the art world, but independent of it, and in conjunction with the existing and emergent nexus of social and political resistance that is evolving in response to the rise of contemporary neo-fascism globally.

Everything Old is New Again

The MAGA movement is the contemporary expression of an ideological trajectory that extends back decades, to the Nixon administration’s Southern Strategy during the late 1960’s and the subsequent transformation of the Republican Party into an instrument of white supremacy, through the deliberate cultivation of racist discourse, necessary to draw working class voters away from the Democratic Party. The roots of this long-standing conservative strategy lie with figures such as George Wallace, Ronald Reagan, Paul Weyrich, Lee Atwater, Patrick Buchanan, David Duke and many others. As I write this, there are protests on the streets of San Diego and Los Angeles against militarized ICE agents indiscriminately arresting otherwise law-abiding individuals who they merely “suspect” of being undocumented. In response, Trump has mobilized thousands of National Guard troops, along with a battalion of Marines, to patrol Los Angeles, in direct opposition to the expressed wishes of California’s governor and the city’s mayor. This has, of course, only exacerbated tensions and increased the likelihood of violence, but that is clearly the point. Given the fact that the small and initially peaceful protests could easily be handled by the LAPD (one of the largest police forces in the world, with extensive training in crowd control), this excessive gesture was clearly intended to inflame the situation on the ground, provoking a counter-response that would justify the domestic use of the military to quell broader forms of dissent against Trump’s regime. The same President who unilaterally pardoned the violent insurrectionists of January 6 (and who is, himself, a convicted felon), now has the audacity to pose as a champion of law and order. The last time the National Guard was deployed by a president and imposed on a state over the objections of its governor was during the Ole Miss Riot of 1962, when the white supremacist progenitors of today’s MAGA conservatives, led by Edwin Walker, attacked federal marshals sent to protect James Meredith from violence as he tried to attend classes at the University of Mississippi. The irony of their descendants now calling up the National Guard to facilitate the arrest and expulsion of peaceful immigrants (identified primarily by their skin color) on the streets of America’s cities is no doubt lost on them, but this historical context should remain central to our understanding of the current moment.

As with any period of authoritarian resurgence the rise of neo-fascism has fundamentally altered existing power structures in the U.S.; both intensifying, and transforming, previous patterns of domination. At the ideological level long established norms of liberal governance, however flawed they might be, have begun to dissolve under a concerted attack by an alliance of corporate elites, white supremacists, neo-Nazis and theocratic Christians, operating under the legitimating umbrella of the Republican Party. At the same time, new oppositional coalitions are emerging, and will continue to emerge, as well as new and unexpected vectors of resistance. Everything has changed, and nothing has changed. The struggle for liberation will, as it always has, learn to adapt to these new forms of repression, creatively, generatively, and subversively. FIELD hopes to continue to be there to document, reflect on, and support this unfolding process. We have only managed to survive as a publication for the past decade through the hard work and commitment of dozens of contributors and editorial collective members. I want to express my tremendous gratitude for the remarkable contributions made by all our writers, and especially by the esteemed members of FIELD’s editorial collective, who have worked tirelessly to keep this unique enterprise moving forward.

Efficacy, Engagement and Fugitivity

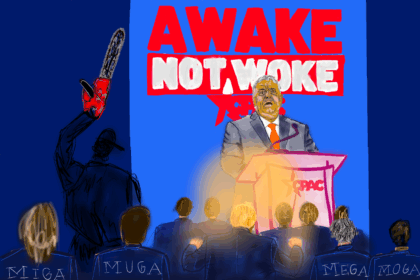

For our tenth anniversary issue FIELD has commissioned several essays that explore a set of key methodological, evaluative, theoretical and practical issues in contemporary socially engaged art criticism. Eva Marxen and David Castenada’s essay, “Social Art Practice and the Problem of Efficacy,” considers the complex role of symbolic capital and institutional capture in the discourse of socially engaged art, and determinations of its critical efficacy. They also highlight the problematic Eurocentrism of dominant traditions of “social” art practice and institutional critique, pointing instead to the important contributions made by fields such as Indigenous Studies. Emmanuel Meschini’s essay, “Becoming Engaged: A Subjective Cartography of Art and Policy in Italy,” explores the evolution of engaged art practice in Italy and the belated impact of neo-liberal economic policies on art and urban redevelopment. Drawing on his experiences as both a practitioner and a historian, Meschini establishes a new genealogy, and vocabulary, for engaged art that is attentive to the unique conditions of this practice in the Italian context. Kevin Ryan, in “Enclosure and Capture: The Paradox of Opacity/Legibility,” employs Marquis Bey’s concept of “fugitivity” to overcome the paralysis that can accompany our recognition of the inevitably compromised and incomplete quality of all forms of political resistance. Ryan encourages us to move beyond a concern with the ontological differentiation of art from non-art as the primary engine of creative innovation, and instead to focus on the complex entanglements of art and praxis. Finally, Noelle English, in her essay, “An Experiment in Art Writing,” employs an ethnographic methodology to detail the insights gained through her involvement with the project People’s Land Trust (PLoT 2220) from 2020, which involved a group of artists working to establish a community land trust in Cork, Ireland. English’s essay explores the interrelated processes of observation, transcription and interaction, necessary to learn, and write, about this work. We are also delighted to present Theodore A. Harris’s timely photomontage work, The Capitol Vetoed. Harris is an innovative Philadelphia-based artist who works across collage, sculpture and conceptual art genres to create incisive critiques of the complex cultural politics of racism, carrying forward the essential traditions of an anti-racist poetics pioneered by his mentor and collaborator, Amiri Baraka. Finally, our spring issue features the most recent series of FIELD “Global Reports” on responses to rising authoritarianism around the world, curated by Greg Sholette. This issue includes reports from Serbia, North Macedonia and Hungary. FIELD can be found at: www.field-journal.com

Grant Kester