Interview with Theodore A. Harris

Laura Thompson

Theodore A. Harris is a Philadelphia-based visual artist and poet, whose work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Harris is the co-founder of the Anti-Graffiti Network/Philadelphia Mural Arts Program and is the Founding Artistic Director of The Institute for Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics. In addition, Harris has co-authored and authored several books including Our Flesh of Flames (2019), Malcolm X as Ideology (2008) with Amiri Baraka, TRIPTYCH with Amiri Baraka and Jack Hirschman (2011), i ran from it and was still in it with Fred Moten (2007), and Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism (2017). The interview below is the product of conversations from Fall 2021 through Spring 2022 via both live video conferencing software and textual exchanges between Harris and Laura Thompson. The discussion sheds light on Harris’s background, his past and present artistic production, and role as a writer, educator, and collaborator.

Laura Thompson: You are a community organizer, an activist, a writer, and an artist. When you were younger what did you hope to be and at what point was it clear that this would be your path?

Theodore A. Harris: Thanks for inviting me to be in conversation with you. When I was a kid, I wanted to play baseball. It’s funny I never really think of myself as a community organizer per se, but I guess you’re right in the sense that my earliest organizing was when I was on the youth committee and co-founder with the Anti-Graffiti Network—later Task Force—which was started by Tim Spencer and Gordan Cooper. Tim was our leader and a community organizer in the West Philly 34th Street Mantua area when it started. The Youth Committee was made up of wall writers/graffiti artists. Me and my friends—EN (Extra Nasty), Chamise, Tim [Spencer], and Gordan [Cooper]—were looking to be examples of wall writers who turned over a new leaf and used our talent in more constructive ways and tried to get other wall writers to help lessen the graffiti in Philly by not writing on walls and taking art workshops and showing work in exhibitions, such as the first group graffiti art show in Philly in 1984, which Tim and the Makler Gallery mounted with writers from New York, including Dondi, Lady Pink, Futura 2000, Crash, Toxic (Torrick Ablack), Daze, and A-one. My tag was KNIFE. In preparing for this interview, curator Sid Sach’s catalog Invisible City: Philadelphia and the Vernacular Avant-garde reminded me of who was in that Makler show. When Wilson Goode was elected the first Black mayor of Philly, he asked Tim to make the program a part of the city government and shortly after that he hired muralist Jane Golden to run the mural program of the Task Force. After Tim died, Jane was able to expand the program into The Mural Arts Program—one of the largest arts programs in the country. Check out the book Philadelphia Murals and the Stories They Tell for a more detailed history. While working on the mural crew, I always had a practice of making visual art and reading and writing poetry. Later, I became interested in collaging after the Challenger spacecraft exploded in 1986. In the Task Force office, I cut out images of it from the newspaper and xeroxed them and glued them down with other images of that awful explosion.

It became clear to me over time this was my path when I knew there was nothing I’d rather be doing than making a contribution to the humanities by helping my community in the arts like the great artists and activists, whose shoulders I stand on to make this world a more just place for all people.

LT: You are primarily from and have continued to base your art practice in Philadelphia. How has this impacted your work?

TAH: I was born in Manhattan and raised in Philly and my sister Brandye was born in Philly. I rarely get asked this and it’s a great question and it will take another lifetime to answer. But off the top, my mother loved music and jazz in particular. When jazz clubs were around in Philly, she worked at the Aqua lounge on 52nd street in West Philly where you could hear Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Art Blakley and the Jazz Messengers. Roy Ayers would come to Philly to play there, so this music was also being played in our home and gave me a sense of the power of a Black Aesthetic through the great music by Gamble and Huff. My uncle Kevin Jamison is a drummer and co-founded a short-lived band named Gas Heat when I was a kid, so I witnessed artists making work before my eyes. My first book on an artist that my uncle gave me was about Norman Rockwell. So, I carry the music in my bones like vibraphone mallets, which is evident in my poetry, then my visual art. And there is the racial violence against our community ever since Black people have been here and my work is a visual and literary trauma response to our past and present nightmares you don’t have to be asleep to see or experience.

LT: You are the Director and Founder of The Institute for the Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics. What led you to spearhead this project? What is some of the work that the Institute is engaged in? Is teaching and education an important part of your practice?

TAH: I got the idea, when I heard Baraka say to Askia Muhammad Touré in a conversation about institution building: “We need an Institute for the Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics.” It just sounded good to me and around this time I was dealing with this question what are Black Aesthetics, so the idea was perfect for me to form an educational project using my personal library as a resource center and non-lending library for art nerds, students writing dissertations, art historians, or lay people who want to learn. To give it some legs, I curated two exhibitions…These shows were only done around subjects I was dealing with in my own work, but I wanted to see how other artists were dealing with the subjects and it was important to be intergenerational and include people from all walks of life. I got no grants, only free space and the shows were great. [1]

LT: To that end, Gene Ray has described your work as functioning in three manners: to remember, to unmask, and to call to action. Do you agree with this characterization and when you make your work, do you have a specific audience in mind?

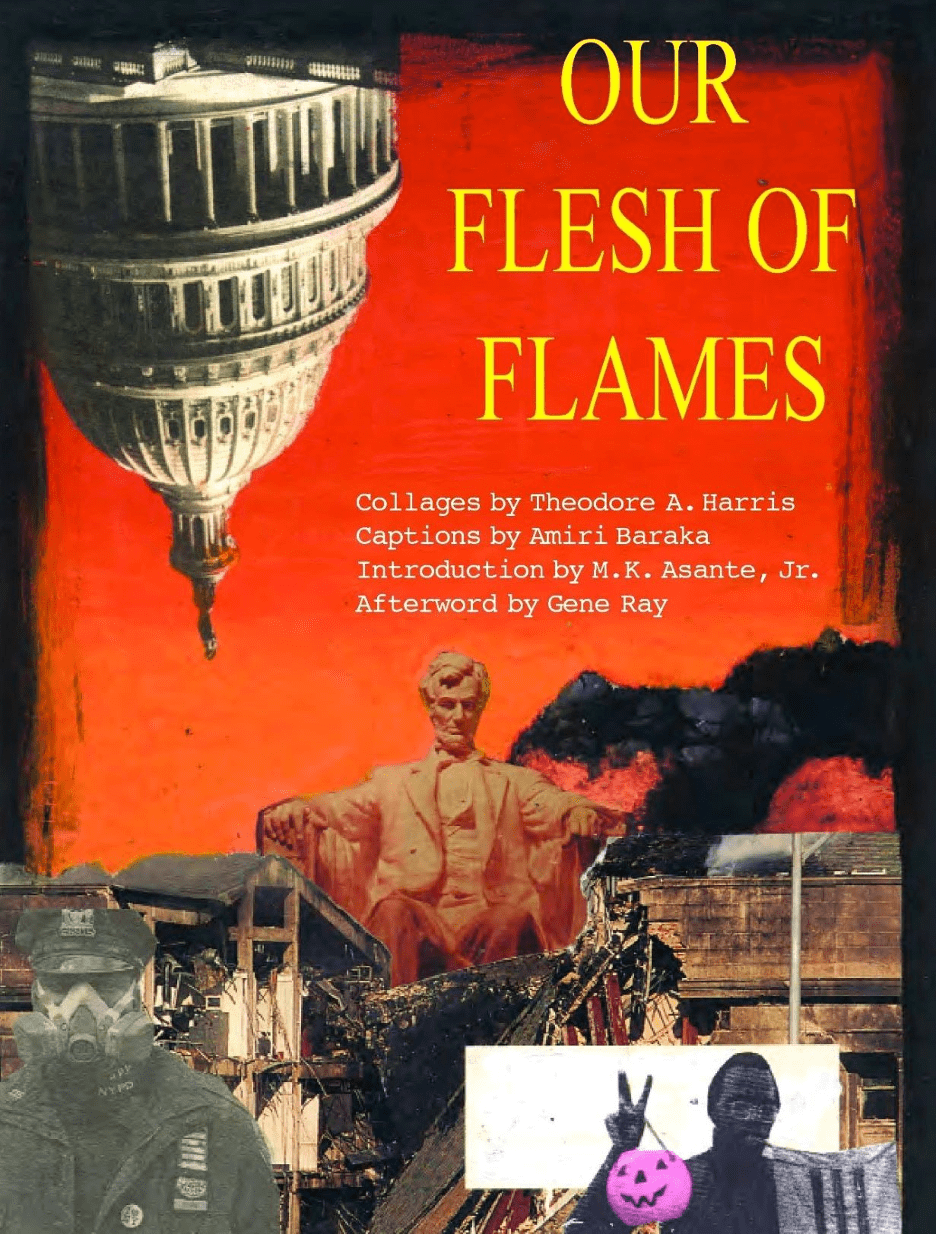

TAH: Yes, Gene is right and the great thing about his Afterword essay in Our Flesh of Flames—the book I co-authored with Amiri Baraka—is that he puts the work in the tradition of other artists like John Heartfield, Martha Rosler, and Peter Kennard, but I’m not only influenced by collagist of course. Yes, I like to think of collage as a memory saver as it helps us see just how much the past is in the present just by using past and current images. A collagist is a surgeon who put the past and present back together again and we need that even more now with the way a lot people in this country are proud anti-intellectuals, so the artist, critics, historians have to combat this sickness that I’m afraid will create more white supremacists, which is what they want to do and have been doing. That breach of the Capitol, was like a bouncy house at a white supremacist block party, letting the world know how powerful lies are when you want to believe them, which should come with a life sentence in jail.

I was rappin’ about this question of audience with Kirsten Prevellet and Jonathan Eburne in BOMB and ASAP/J. It’s a good one because for me what I’m hoping for is an anti-formalist reading of the work. As an artist you are also an audience member when viewing other artists’ work, but I’m not the kind of artist who is into keeping people guessing and I’m with Kerry James Marshall on this, when he says there are no secrets in why or how he makes the work and that doesn’t stop me from looking deeper. Some artists think if their work is ambiguous that’s what makes it art. You won’t like my work if you’re anti-intellectual. If you’re a person who has been following my work or not, I would hope you come with your own life experiences which will inform you that I’m challenging myself as an artist to make the kind of work I want to see and read. Like Barnett Newman said in Tiger’s Eye, “An artist paints so that he will have something to look at; at times he must write so that he will also have something to read.” [2] So, with the Thesentür series I hope to bring you into reading a circle or book club to learn more about the artist and critics that shape my thinking about art and its function in our lives as human beings.

LT: As you have alluded to, your work has been interpreted as collapsing the past and the present through collage, which indicates that some of your work functions as trans-temporal entities; collage as both a record of the time and a lens through which we can view the past through the perspective of the present. Would you agree with that assessment? And do you view your work as engaging with and looking to the future?

TAH: Because with collage you can deal with some very old images and very current images at the same time, a third meaning makes you contemplate where these things intersect and create some type of allegory, it creates a third meaning in your mind. And I think what they hopefully say is let’s not repeat these historical traumas, these historical injustices. So hopefully its saying that was the past but look it’s also in the current future. It’s also in the present that we’re living in and repeating some of the same things. So, let’s go into the future, like with what David Craven was saying about collages was that hopefully we won’t have to make these kinds of images in the future; it will be something of the past. You know it’s about learning from the past in the present and going forward with our best lives without having to deal with these things. So that’s the hope. Artist Steve Locke said: one day I woke up and I was wondering what kind of work would I be making today if there wasn’t racism? So that’s what we hope and what we try to build. That’s what we try to get past.

LT: It’s interesting to hear you talk about creating a third meeting through allegory and collage; that it’s in the mind of the viewer where a new piece is created looking toward the future as a warning. This reminds me of the introduction from Our Flesh of Flames in which M.K. Asante characterizes your collaborations with Baraka as Emergency art that is consciousness raising. Do you think of your work in that way?

TAH: I never use the words emergency art because it’s all a crisis, many different crises. I mean, how much can people bear? When you think about the historical stuff and you have this current stuff going on…I mean, when those people breached the Capitol building, I was astonished. But it’s not like these things haven’t happened before, especially during the Reconstruction period with suppressing the vote. You know there was death and dying with that, but it let me know that these people are kind of settled in the dark. People want to believe something, no matter what people are proving. Here’s the proof that the vote was fair. You don’t want to believe it because you have an agenda that was to keep you in power. And they are going to say antifa was there, Black Lives Matter had something to do with it, that they were disguised… About 60 federal judges said, no the vote was fair. Republican and democratic elected judges—even the Trump elected judges. But they want to try it again, and they are going to try it again. So, they need to believe something that’s not true to stay in power and it’s so dangerous… This is the emergency…

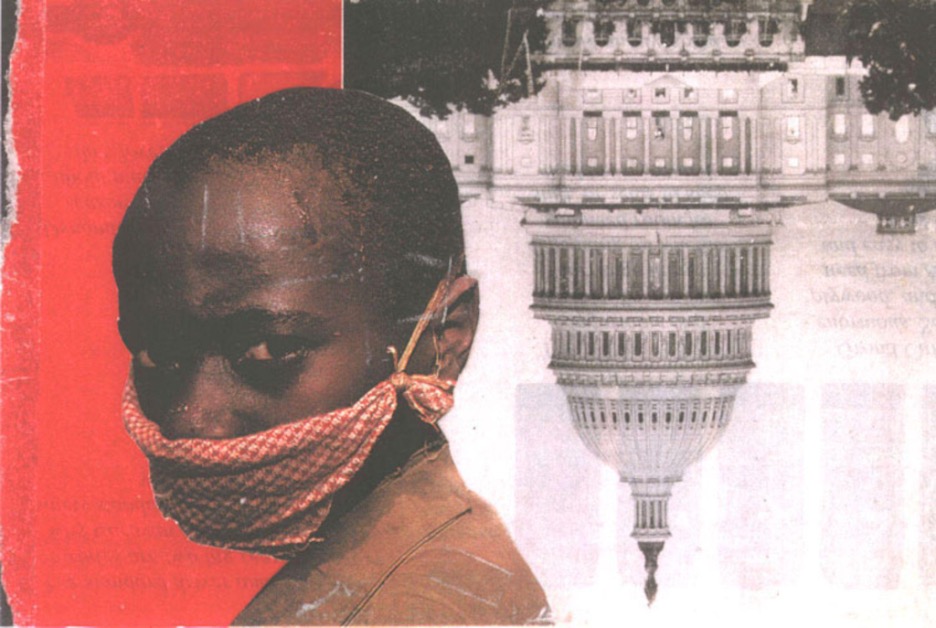

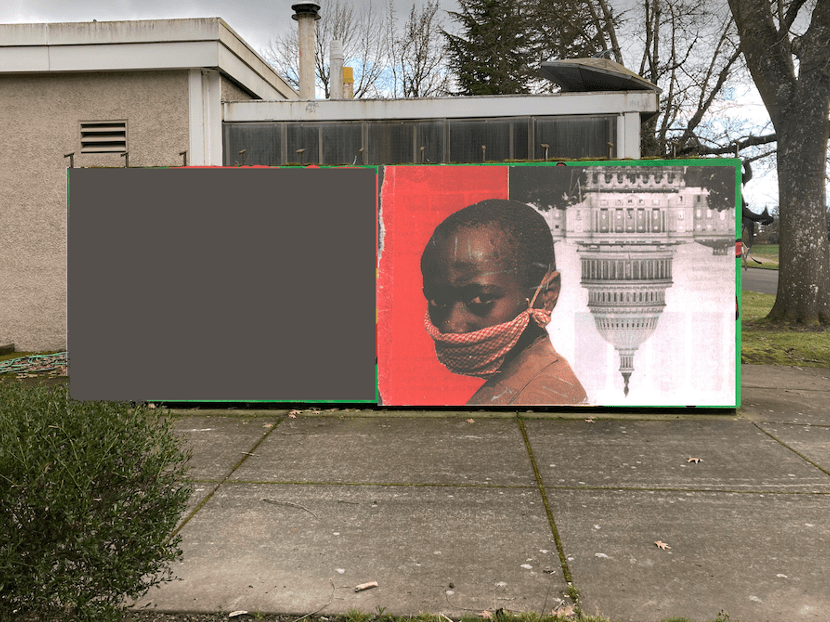

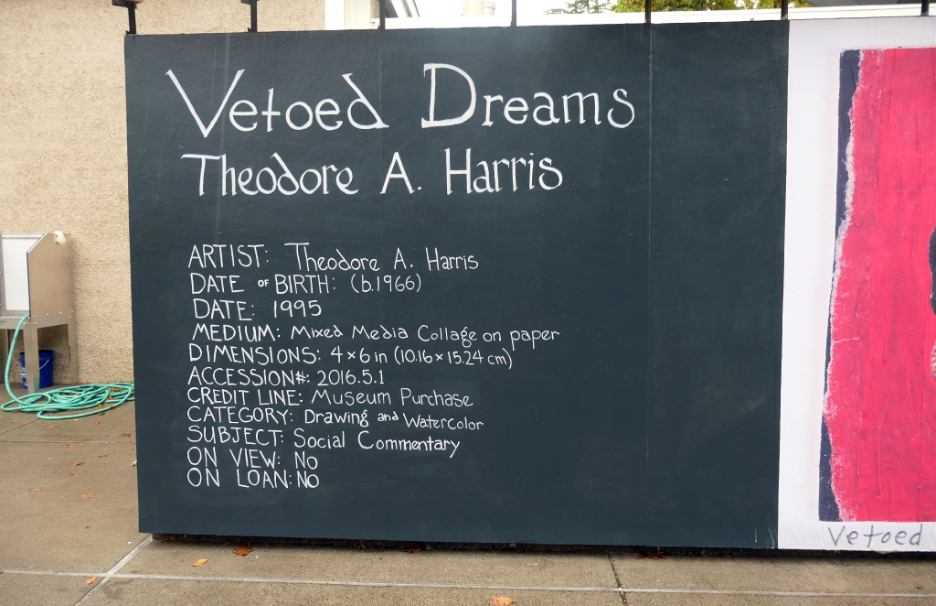

LT: To indicate this you tend use of inversion as a visual strategy. Most notably, you invert the US capitol in many of your collages, a tactic that Amiri Baraka has likened to a bomb. You have also referred to it as functioning as set design to signify a theater of white supremacy. Given the events of the January 6 insurrection, your remarks seem particularly apt. What led you to use the capitol in your work initially and are there other images or symbols that you think also represent the intersection of power, capitalism, and racism?

TAH: Yes, I think it was at Stanford University where I remember Baraka pointing to a projection of Vetoed Dreams on the screen and saying the inverted Capitol looked like a bomb. The theater historian Harry Elam and The Committee on Black Performing Arts invited us to exhibit the colleges and the captions he wrote for them, this was before the book was published. But it was also around the time Baraka was getting heat for his great poem Somebody Blew Up America in response to 9-11. Our very first presentation of the project was at Haverford College. After the Supreme Court took the voting rights act off life support to disempower marginalized groups—so as long as that’s the case—the Capitol will stay inverted in my work.

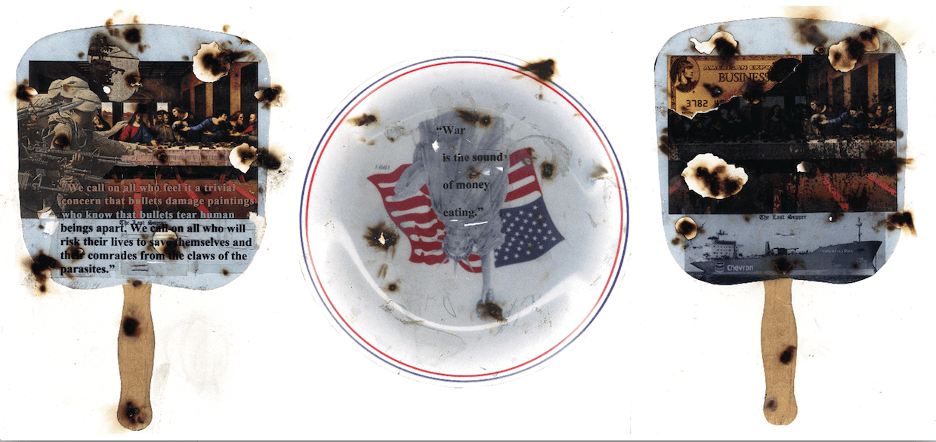

LT: You mention Baraka, whose spoken poetry is so powerful paired with your images. Your collaborations teem with a sense of urgency, which recalls your more recent work Collage and Conflict, produced by Andrew Goodwin. In this video piece, you are giving a spoken word performance as images of your collages are projected onto your body. For me, it is so powerful seeing your work in that way in which your body as the artist becomes part of your collage work. The viscerality of the series in which wounds, burn marks, and bullet holes penetrate the image surface bespeaks the urgency of human precarity that lies at the heart of American capitalism, militarism, and police brutality. Is this type of video performance something you see yourself doing more of in the future?

TAH: Yeah, I would like to do something like that again. I like the experimental quality of the montage projections. I’m glad you brought up working in film/video. While I was at Linfield University doing the residency, I met the great photographer/cinematographer Kahlil Pedizisai and he introduced me to two of his students Andrew Goodwin and Jordan Simmons, who made two video projects of my work with my voice over reading from the Collage and Conflict Manifesto, which gave me ideas for video montages. For this interview I wanted to make new work, so I asked Andrew and Jordan to make still images from the videos at certain points where the video creates a cross fade montage.

LT: Your work has been described as a visual manifesto—a rather apt description given its explosive power and immediacy. But I also find that the more time I spend with one of your collages, more layers of meaning reveal themselves. Could you talk about your process of making?

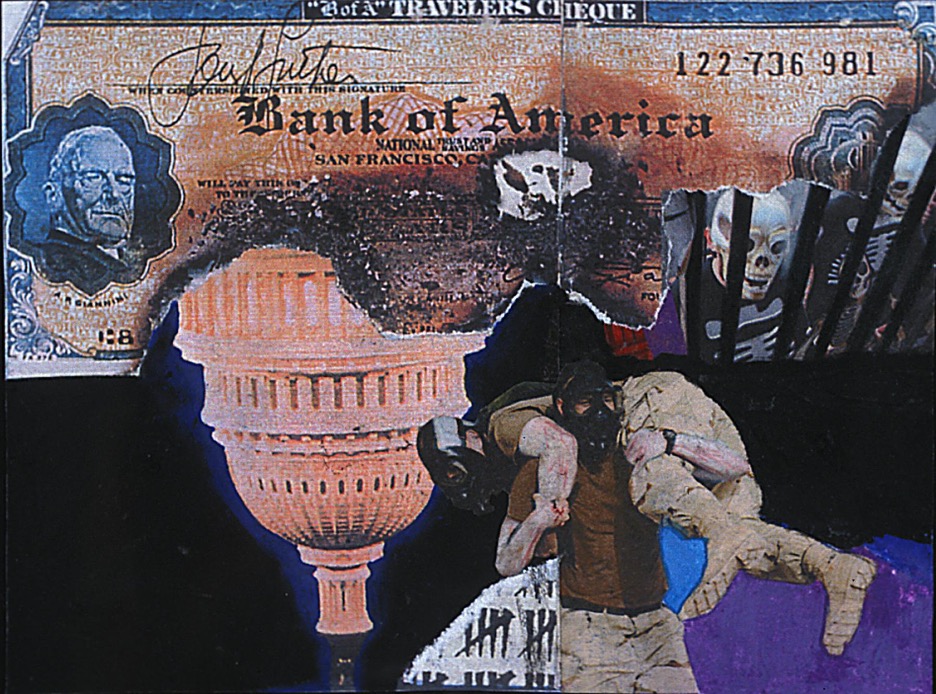

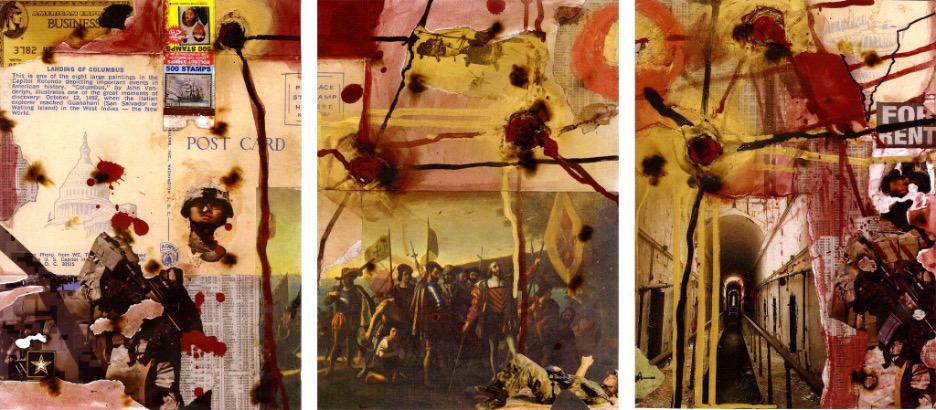

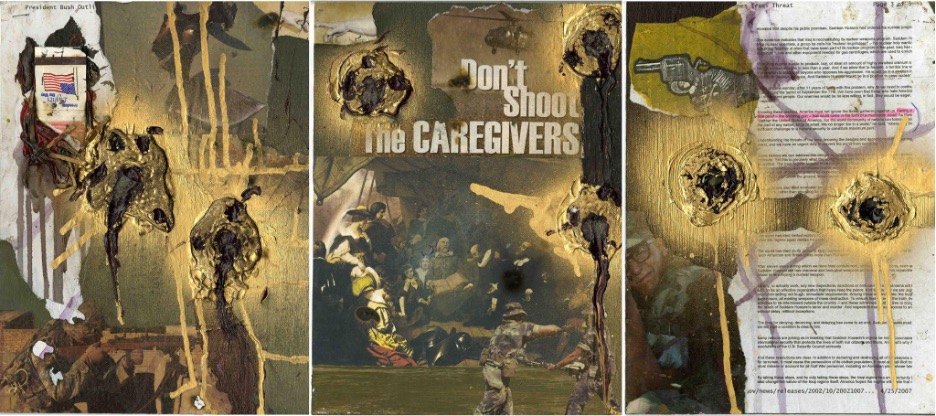

TAH: When I come across an image my instinct is to think to appropriate the image the right way. I find something that’s the opposite so that a third or many meanings unfold when I collapse them together. For the Thesentür series, it’s more minimal—just text and image. The text is a critical art thought bubble they [the imaged subject] would not think or say. The collages are mixed media and I use images from newspapers, magazines, found objects, and for color and texture I’ll use oil sticks and bind them with glue sticks onto paper or board. With the Collage and Conflict series I knew as the series grew, I wanted the surface to be more and more visceral, abraded. I wanted the wounds on the surface to be raised to create a connection with the collaged images to be cinematic. In the center panels of Postcard from Conquest and Don’t Shoot the Caregivers are images from two of the paintings in the Capitol rotunda that lie about the founding of this country. The idea of adding the soldiers is out of Leon Golub and the wounded surface. I’m pretty sure it’s the influence of the Vienna Actionists Hermann Nitsch and Günter Brus.

LT: More generally, what principles guide your work? Have these principles shifted over your career?

TAH: I’m thinking more deeply about art and ethics in art criticism, how marginalized groups have been treated in its “Stop and Frisk ” treatment of Black and Brown artists and even white women artists. For a new Thesentür series I’m working on, the text says: “They are deaccessioning their masters to acquire more ex-slaves and white women to diversify their collections.” Here, the Philadelphia Art Museum has never ever had—since it was built on stolen land—an on-staff, a full-time African American curator and we have issues with that. It might take some form of protest to get it understood that you can’t just take taxes from Black people that help the museum operate and act like you don’t see us.

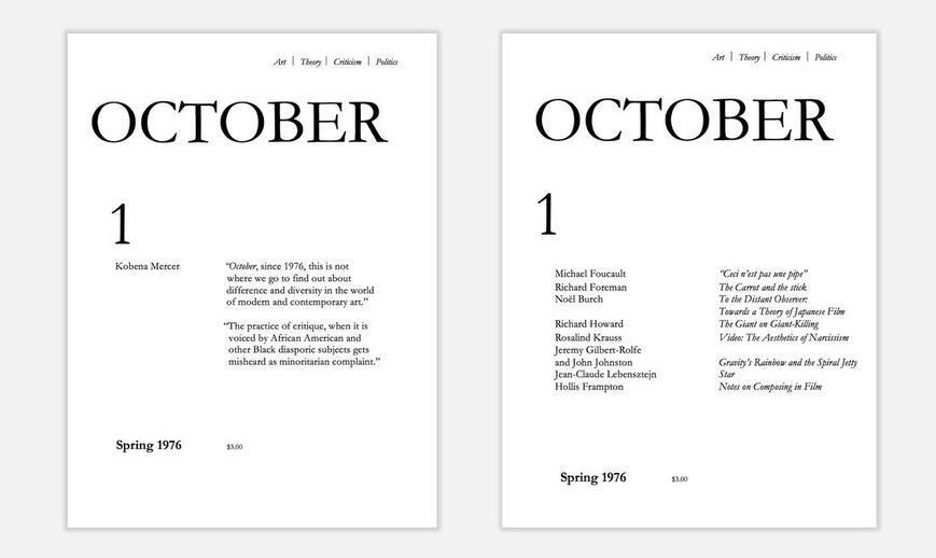

This brings to mind, I’ll never forget, when the art historian Kobena Mercer was on a panel for The Vera List Center for Art Politics years ago, he said something that articulates this crisis. So, I made a double cover work of the journal October on which I put his statement on the left panel and the right is the original cover: “October: Since 1976, this is not where we go to find out about difference and diversity in the world of modern and contemporary art. The practice of critique when it is voiced by African American and Black diasporic subjects gets misheard as majoritarian complaint.”

LT: Your use of the diptych and triptych seems to allude to the theme of religion as an instrument of power and exploitation. What led you to explore these formats? How is it different from working on a single composition?

TAH: To be honest I never gave thought to the triptych being a religious art form. I just knew I needed a form that would help me expand the collage form in size from my usual 8 ½ x 11 in or 11 x 17 in formats that I used for the most part. I also made some diptychs recently. I was looking closer at Francis Bacon’s triptychs and Basquiat’s work and its reception in the art world; you can see his influence in the first triptych titled after a book of essays by Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism. After that work, I decided to title the series Collage and Conflict.

LT: Collage is a medium that has long served as a powerful instrument for political critique and dissension. In fact, Amiri Baraka and Brian Winkenweder have observed that your work seems to be drawing from a vibrant history of artists, like John Heartfield. Why has collage proved to be such a significant medium in your body of work?

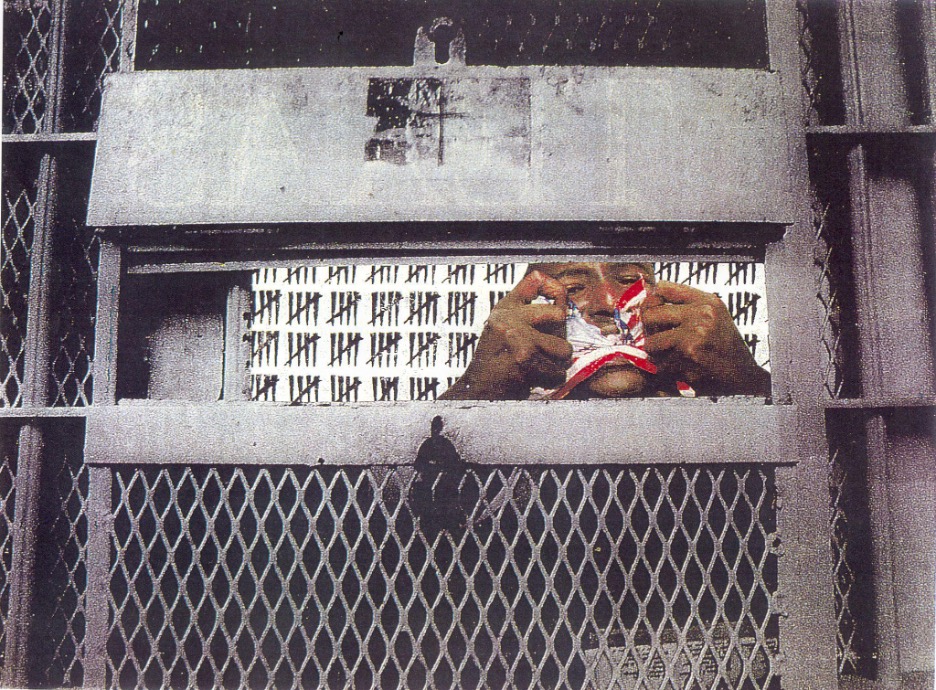

TAH: Baraka said in an essay that the collages were “truthoscopic” in form and content and he also was the first to see my connection to both Heartfield and Romare Bearden. On the collage Led Away to Decay, David Craven wrote, “This collage by Harris is made from photographic fragments of prison architecture, which are composed so as to construct a cramped, visually confining pictorial space in which an inmate is shown eating a flag, as the final consequence of a flag waving system that prizes weapons over food both here and abroad.” [3] As long as they print newspapers and magazines there will be collages made by school children or serious artists which is why it is powerful and the reason why art is not taught in schools in low-income areas. All you need to start is as many newspapers and magazines you can find, scissors, and glues sticks. The more serious you get about using the form the better the work will be.

LT: You have collaborated with Baraka on several occasions, including the book Our Flesh of Flames. How did this project originate?

TAH: Baraka had been using my work for a while in his Unity & Struggle Journal and it just hit me one day to ask him to work on a project where he would write text and a short essay to a few images I selected. When I got the material back from him, he had written captions to the collages. Then, I was going through some files, and I found a short piece he wrote where he connects me to Bearden and Heartfield: “Teddy Harris’ Collages are an innovative and revolutionary popular form, taking recognizable, random and diverse images, and constructing them into sharp social commentary in very skillfully presented graphic wholes. Harris’ work is an art of the everyday given new life and revelational impact. It is as if someone combined the sizzling social statement of Heartfield with the aesthetic penetration of Bearden. That’s right! Check it out.” [4]

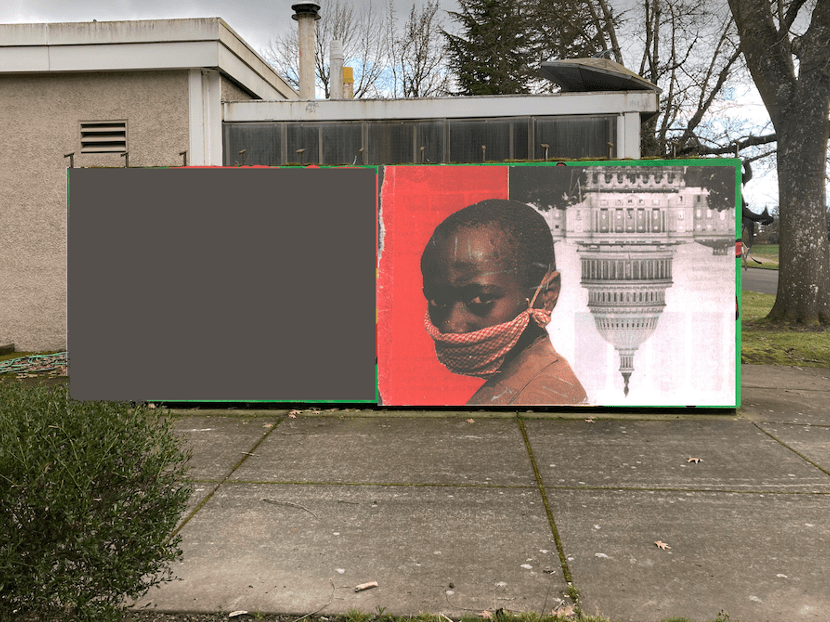

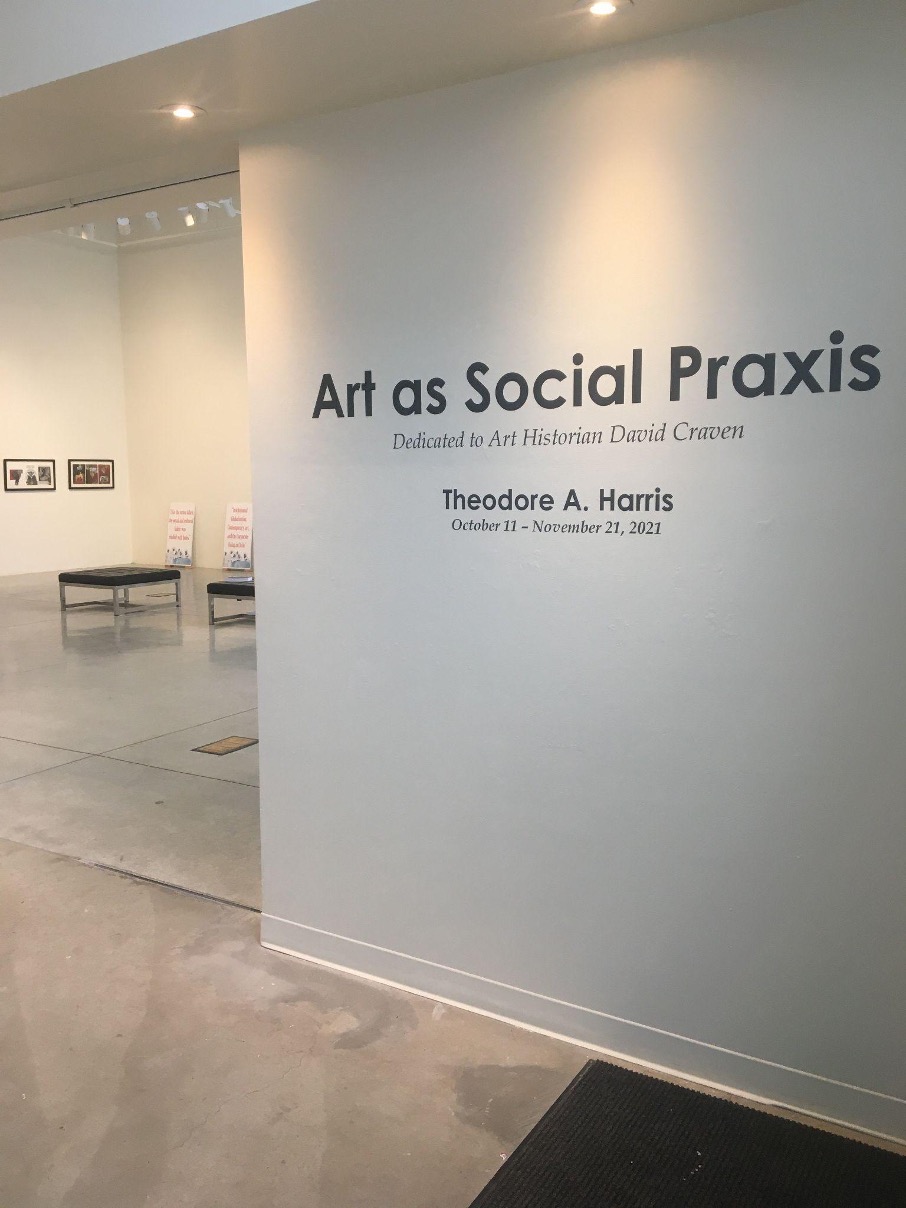

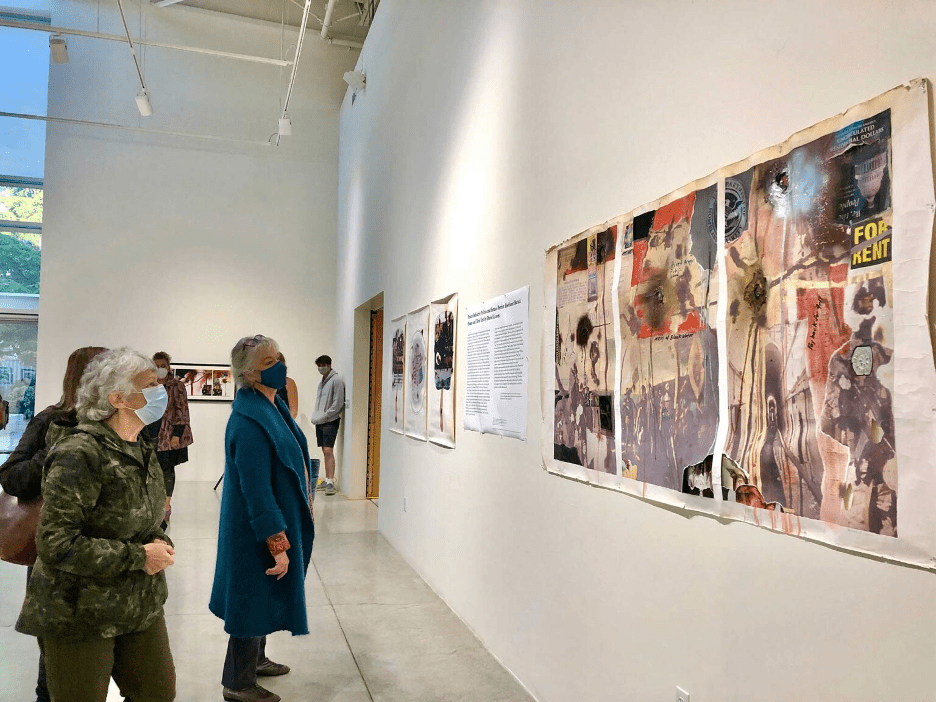

LT: In the exhibition catalog for Theodore Harris: Art as Social Praxis Dedicated to Art Historian David Craven, there are mockups for wheat paste murals of your work enlarged and existing in public space. Do you have plans for more murals like this? How do you think your work operates on this scale and in this context?

TAH: First, I have to give big credit to Thea Gahr—the co-curator of my exhibition at Linfield University—for the idea of creating murals of the collages and for getting the great muralist, Chip Thomas, I worked under to wheat paste the murals. It was great having the two murals on the art department walls and having the solo exhibition in the gallery. Big thanks to art historian Brian Winkenweder for inviting me also to be artist in residence. The great thing about murals is that they are seen by all levels of the public art lovers or not and with collages made into murals, well this is something I have been trying to get done in my own hometown with the organization I co-founded and it still could not get done. I think it’s the inverted image of the Capitol that they don’t want associated with the program because the public wanted the mural of Vetoed Dreams.

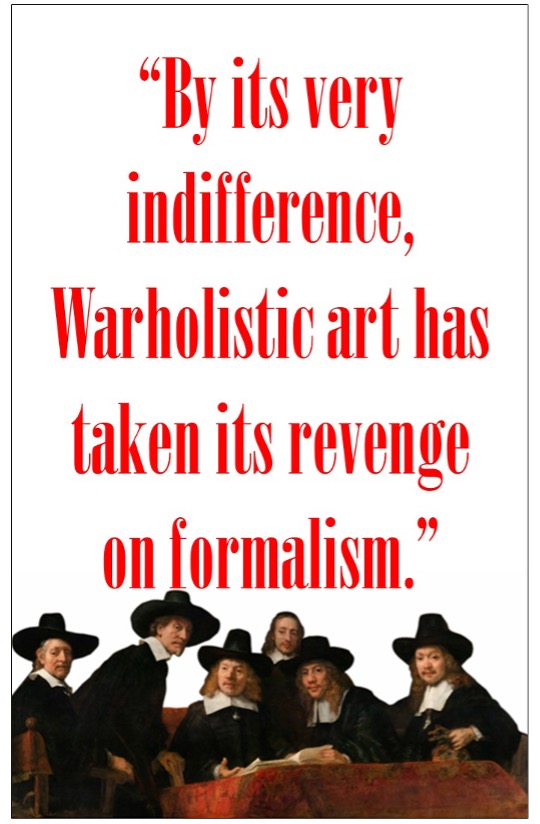

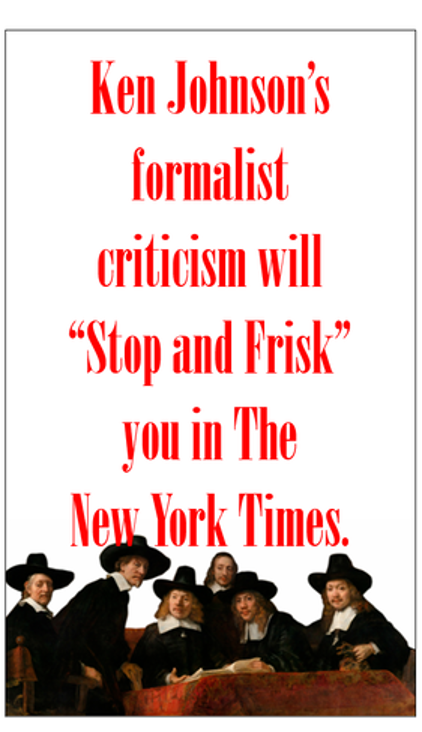

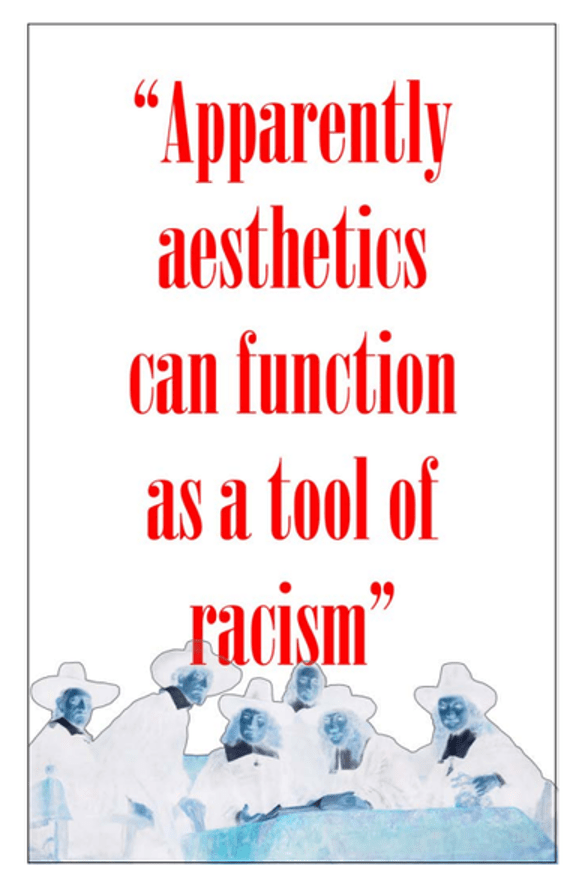

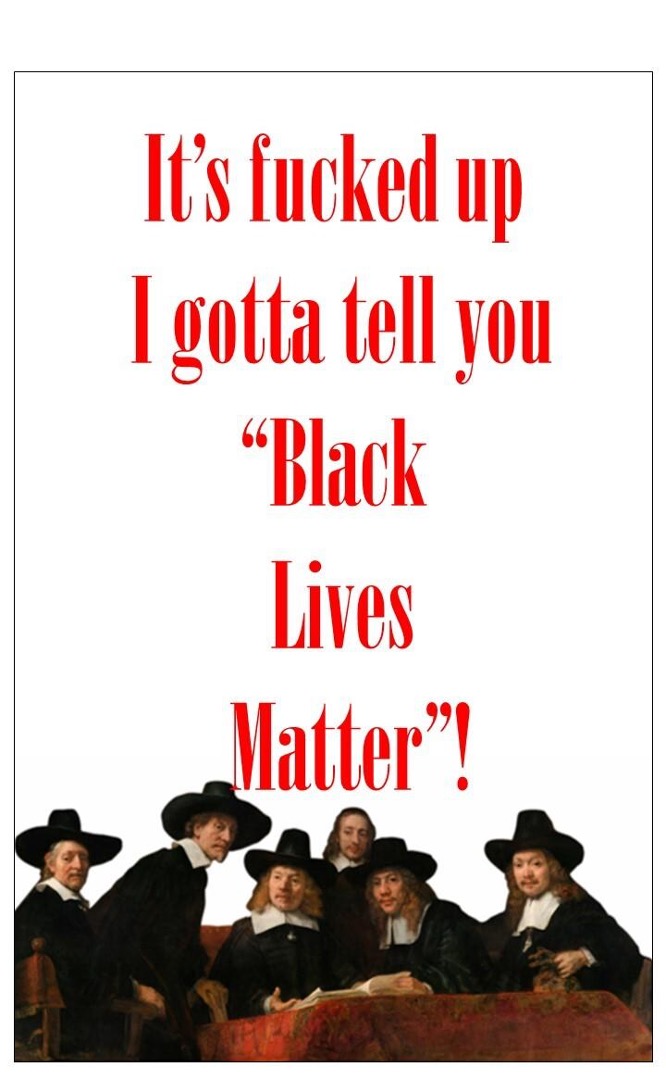

LT: In your recent series Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism, you have appropriated a commercial interpretation of a Rembrandt van Rijn’s “The Syndics,” which alludes to the undercurrent of capitalism and colonialism within the original painting and the iteration of it on a cigar box—a symbol of status, wealth, and masculinity. Pairing this imagery with quotations drawn from well-known art historical texts as a means to critique mainstream attitudes in the field of art analysis is quite compelling, particularly given your nod to Martin Luther’s theses. Could you talk about your Thesentür series? What prompted this body of work?

TAH: In the words of visual artist Benny Andrews “I’m not an art critic, but I cannot in clear conscience let the slighting remarks made by Hilton Kramer go unchallenged.” [5] Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism is a series of minimal image-and quotation-based works that uses poetry to confront mainstream art criticism and art history, to look beneath the surface politics of aesthetics and formalism in a presentation of art that is not self-referential or to put a Black face on the art history of imperialism. Formalism functions as the cosmetics of art criticism like aluminum siding on a slumlord’s property. It is an attempt to disguise what is crumbling beneath the surface politics of its proselytizing church bells, ringing, in the megachurch/museums and galleries where there are more Black bodies guarding the white cube than exhibiting in it. What marginalized artists know is that canon formation is a battlefield and critical art is the weapon! In the crossed-out words of Basquiat to repel ghosts … for this series I have appropriated the image from the Dutch Masters Cigar box which is an edited version of Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Syndics (1666), The Sampling Officials of the Amsterdam Drapers’ Guild who inspected and priced samples of dyed cloth in order to maintain “quality control” for their industry. Here I use the image with text not only to talk back to art history’s critics, but also to the history of the Dutch West India Company who were major traders in the flesh business at the time Rembrandt painted this work. In every Thesentür work, you are confronted with the men in Rembrandt’s Sampling Officials of Amsterdam Drapers’ Guild (1662), facing us like celluloid ghosts from art history’s past, sizing us up, ready to pickpocket our nightmares. If I could go back in time I would ask the men of the Drapers’ Guild what is in that little bag that the man is holding to the right side of the painting: is it profit from the Dutch enSlaved Coast? And what is being recorded in that ledger book on the table, other than the quality of the dyed cloth of which they were the critics, cookin’ the books with Black bodies? I am interested in what the artwork is not telling me about the world in which the artist lived at the time he created this work.

In the October 25, 2012 edition of The New York Times, art critic Ken Johnson wrote a “wrong-headed” review of the historical exhibition Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960 – 1980 curated by Kellie Jones. He negated the worth of the exhibition and focused on the politics of the show—in that all of the artists were Black artists rather than discuss the quality of the work’s form and content. Johnson wrote, “Herein lies the paradox. Black artists did not invent assemblage. In its modern form it was developed by white artists like Picasso, Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp, David Smith and Robert Rauschenberg…” [6] Thesentür/The Thinker: Conscientious Objector to Formalism series, theorized as visual art, is in the tradition of Martin Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the castle church door against indulgences in Wittenberg, Germany. Today, formalism is the communion wafer and the Castel church now is the mega museum where the MAGA hat is a passed around, bottomless collection plate, with millions of dollars spilling from behind the broken walls of Joel Osteen’s church.

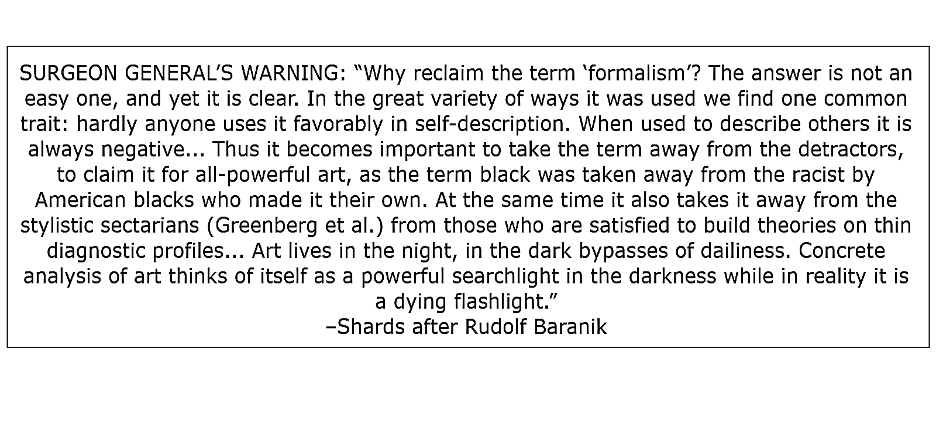

The series allows me to work in minimal form with found text, image, and art historical poetry I write. While I was working on the Thesentür series, I was also working on the Surgeon General Warning series, which also deals with some of the same issues but in a different form. While working on it, I found a great essay by the painter and writer Rudolf Baranik and I made a work from titled After Rudolf Baranik 2.

I’m experimenting with the Thesentür series by adding an image of Rodin’s sculpture, The Thinker, to see what the Rembrandt’s Drapers’ Guild has in common with it. In addition, the title has changed to Thesentür /The Thinker: “What was The Thinker, Thinking about Colonialism?” This is a line Baraka wrote in an essay on the artist Thornton Dial in the book he co-authored with Thomas McEvilley titled Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger. It’s a powerful line that made me look harder at The Thinker here at the Rodin Museum in Philly. Jennifer Thompson curator at the Rodin Museum said:

I like Amiri Baraka’s line “what was the The Thinker, thinking about Colonialism?” It provides a good framework for the Thesentür/The Thinker project and potentially for museum visitors. It makes me think of French colonialism in the 1880s and beyond. You are absolutely correct that Rodin modeled The Thinker around 1880, exhibited it for the first time in 1889, and had a large-sized plaster version installed outside the Pantheon where it received a fair amount of criticism and controversy in 1904. At the same moment, the Garden of Tropical Agriculture opened on the outskirts of Paris. It hosted the 1907 Colonial Exposition, which included human zoos from each of the French colonies. [7]

LT: Where do you feel art as social praxis is heading in the future?

TAH: If social praxis is defined by more practice than theory I feel somewhere in the middle because what I’m trying to do is look beneath the surface politics of aesthetics and formalism, because it’s got the point where we have to put signs in our windows to remind people Black Lives Matter! because the real “cancel culture” is the unlawful police violence of formalist hawks that cancel our lives.

LT: Lastly, are you working on any new projects? Where do you envision your own work to be heading in the future?

TAH: I am working on the Thesentür/The Thinker series and writing. Everything has to be done in the service of preventing the anti-intellectual formalist hawks from overthrowing the government in another coup attempt, because of their whiteness and therefore power over our lives is threatened. For us the victims of their centuries of weaponizing their whiteness as a colonizers ideology we see their whiteness as a “false flag operation.” Thanks, it’s been great rappin’ with you.

LT: Thank you!

Theodore A. Harris is a Philadelphia-based visual artist and poet. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and is in private and public collections such as University of New Mexico Art Museum, Saint Louis University Museum of Art, La Salle University Art Museum, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, McGill University Visual Arts Collection, Center for Africana Studies; University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center Rare Books and Manuscript Library; University of Pennsylvania, and the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, and the Winston and Carolyn Lowe Collection. Harris is the co-founder of the Anti-Graffiti Network/Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. Harris has also co-authored and authored books including Our Flesh of Flames (2019), Malcolm X as Ideology (2008) with Amiri Baraka, TRIPTYCH with Amiri Baraka and Jack Hirschman (2011), i ran from it and was still in it with Fred Moten (2007), and Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism (2017). He is the Founding Artistic Director of The Institute for Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics. His recent exhibition Theodore A. Harris: Art as Social Praxis Dedicated to Art Historian David Craven, was mounted at Linfield University 2021 and was curated by Brian Winkenweder and Thea Gahr. He is a 2022 CFEVA Visual Artist Fellow (Center for Emerging Visual Artists).

Laura Thompson is a Ph.D. student in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the University of California, San Diego and a member of FIELD’s editorial collective.

Notes:

[1] For example: Shut Your Trap!: A Study on Authority in Art and Surface Politics: Looking Beneath Aesthetics and Formalism. See: Theodore A. Harris Fourth Wall Artist Profile on Vimeo

[2] Barnett Newman, Tiger’s Eye (1947) From, “The Ideas of Art: The Attitudes of Ten Artists on Their Art and Contemporaneousness,” in Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John P. O’Neill (New York: Knopf, 1990), 160.

[3] David Craven, “Present Indicative Politics and Future Perfect Positions Barack Obama and Third Text,” Third Text, vol. 23, issue 5, September 2009, p. 647.

[4] Amiri Baraka, “Our Flesh of Flames,” Callaloo, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Winter, 2003), p. 129.

[5] Benny Andrews, “On Understanding Black Art,” New York Times, June 21, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/21/archives/on-understanding-black-art-toward-an-understanding-of-black-art.html.

[6] Ken Johnson, “Forged From the Fires of the 1960s,” The New York Times, October 25, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/26/arts/design/now-dig-this-art-black-los-angeles-at-moma-ps1.html.

[7] Email exchange between Jennifer Thompson and Theodore Harris on January 6, 2022.