Alternative Spaces: Site-Conscious Practice in Contemporary Art from Tehran (1990s-2010s)

Helia Darabi

One day in the fall of 2002, at the heart of Tehran, a group of young men and women, dressed up in dark overall costumes with faces covered, blocked the entrance of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art using barbed wire and forbade the enthusiastic opening audience from entering the show. They held signs and placards that harshly warned the audience against encountering the works of art. They captured a few people and tied them to the museum railing and blocked the Museum Director, Alireza Sami Azar, at the entrance.

It was a performance acted by a dozen of young art students and directed by their professors. They might be considered the third generation of post-revolutionary artists directly interacting with the most iconic contemporary art institution in Iran. Although it might be hard to imagine that such a radical work would be accepted and executed in an official, state-run institution given Iran’s highly restricted political atmosphere, it was one example of many site-specific and critical practices in Tehran during recent decades, whether happening within the frame of formal institutions or without in the urban space.

In this survey, I will focus on various tendencies in contemporary art in Iran which manifest an entangled encounter with the site. As suggested by its name, a site-specific work is a work of art that is vitally dependent on or inseparable from its site. It starts a dialogue with the site and uses the space itself as a medium. Miwon Kwon defines site-specificity as a critical practice framed by phenomenological, institutional, and social contexts [1]. Nick Kaye proposes that site-specificity can be understood in terms of a process, while “a ‘site-specific work’ might articulate and define itself through properties, qualities or meanings produced in specific relationships between an ‘object’ or ‘event’ and a position it occupies [2].” Kaye continues that “site specificity derives from the delineation and examination of the site of the gallery in relation to space unconfined by the gallery and in relation to the spectator [3].” A glance at the extensive literature in the field, however, reveals various interpretations of the term provided according to context, which makes it difficult to reach a straightforward definition [4]. The same is true for the term “installation art,” which one might also find applicable to many of the artworks introduced in this essay [5]. I should then clarify that though not all the works presented here can be fit perfectly in a single definition, they all share a conscious, sensible mode of interaction with the sites in which they are created.

This essay is a survey of how contemporary Iranian artists stepped into the “post-studio, post-gallery” paradigm and began to leave the established, conventional venues to re-site and redefine their artworks within alternative spaces. It also includes some of the earliest instances where contemporary Iranian artists embarked on using new artistic means and media, which might have been, in many ways, triggered by their experience engaging with the site and their urge to interact with space. Although more instances of installation and environmental art might be included, I have tried to focus on the pieces whose formation is directly related to the idea of the site, i.e. the works which demonstrate conscious and innovative responses to the formal, contextual, and/or discursive requirements of the site. Save for a few historical examples, all the works discussed here belong to the period between the 1990s and 2010s. This is a period that I identify as an interval, a liminal span of time when the post-Revolutionary artistic community was savoring sips of freedom and enjoying discovering new means of communication in relative independence but was not yet assimilated by the commercial prototypes which were to be consolidated in the following years.

Background

The 1940s was a thriving period for the visual arts in Iran. The establishment of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran and the formation of the first art galleries and artistic groups marked the beginning of a vibrant era of plentiful exploration of new styles and devices of visual representation. The resulting artworks, mostly paintings and less frequently sculptures, were rich in abstract, expressive, imaginative, and ornamental propensities. Rouyin Pakbaz, a pioneer Iranian art historian, emphasizes the generative and lasting values of this art while noting its dependence on Western Modernist formalism and its overall socio-political disinterest [6]. The movement, which was also reinforced by the Tehran Biennial in 1958, gradually gathered a circle of elite audiences in the art galleries and other cultural venues [7]. These artistic events revolved, as mentioned before, around painting and sculpture, and the exhibition space was generally treated as a mere receptacle. It was not until the 1960s that conscious, critical approaches to the exhibition space emerged and artists started to acknowledge and address the potentialities of the site which contained the art pieces.

An early example of a modern engagement with the site was given by Kamran Diba (b. 1937), architect and artist who later designed the outstanding building of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA, 1975-79). Graduated in the 1960s in the U.S., where Neo-Dada and Pop Art were trendy at the time, Diba took on the quotidian subjects and tried to interact with the site and engage its visitors in a manner that might be considered quite radical in the context of the chic, fashionable art galleries in the capital, which showed abstract, mainly decorative Saqqakhaneh paintings and were frequented by the stylish upper-class. Prodigal Waterman (1967), his show in Seyhoun Art Gallery in Tehran, was a multi-media installation using painting, plumbing accessories, and pre-recorded sound [8]. The paintings represented life-size floating figures together with ironic texts written in Nasta’liq calligraphy. The installation was accompanied by a recorded dialogue aimed at disorienting the viewers and challenging their physical situation [9]. In a text written ten years later, Parviz Tanavoli remembers: “At the opening night there were various piping and irrigation accessories, water taps painted blue, some employees of the Tehran Water Recourses Company were present, the sound of water drops… everything was about water [10].” This exhibition is one of the earliest multimedia installation events in Iran which developed a new relationship with the site. It is a pioneering gesture in using unconventional materials, showing an innovative approach to exhibiting, and, I believe, introducing a level of challenging humor to the gallery events which must have displayed a certain elitist, if not snobbish, character at the time. The reference to water might also be interpreted as a challenge to the gallery context: ab baz (in Persian: the one who is a master in staying afloat on water, and as an idiom it implies opportunism) alludes to an overambitious persona that the artist attributes to himself in an ironic gesture [11].

One of the most innovative protagonists of modern Iranian art was Iranian-Armenian artist Marcos Grigorian (1925-2007). A graduate of the Faculty of Fine Arts in Rome, he was inspired by the European Nouveau Réalisme and also became attracted to the New York art scene in the mid-1970s. Pop art and Neo-Dada inspired him to bring elements of everyday life into his art and communicate a fresh awareness of the site [12].In the last years of his residence in pre-Revolutionary Iran, Marco founded the “Azad Group of Painters and Sculptors” together with painter Massoud Arabshahi (1935-2019). The group was officially announced in December 1975 during the First International Art Fair in Tehran.

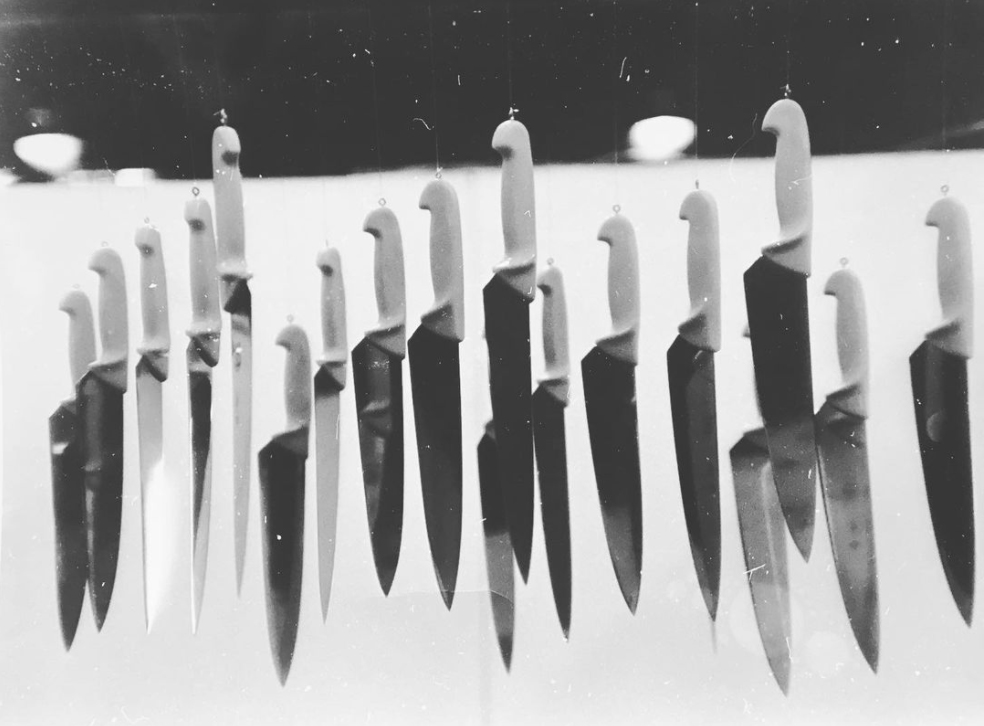

Against the backdrop of an art scene dominated mainly by formalist and abstract tendencies, the Azad Group (1974-77) took on an innovative approach to medium and subject matter. Following their manifesto on the “liberation of art from all restrictions towards the freedom of expression [13],” the group also showed a new attentiveness to the exhibition space. For instance, in one of their exhibitions, titled Gonj o Gostareh (Roughly: Volume and Environment), Marco Grigorian tied an old, broken chair to a fence, covered the room in black, then projected his own portrait onto the installation, as if he himself was tied to the chair [14]. In the third exhibition of the group, Morteza Momayez (1936-2005), the pioneer graphic artist, hung a number of large kitchen knives threateningly from the ceiling of the venue [15].

These early trials marked the beginning of a new type of response to the exhibition site in the context of the Iranian art scene, whose artists until then did not see much creative potential in the exhibition space. Such innovations did not last long, however. Due to the break out of the Islamic Revolution and the subsequent 8-year war with Iraq, the practice of contemporary art, along with many other cultural activities, underwent an interruption. Artists were dispersed, many left the country, and it took nearly two decades for the art scene to gradually regain vitality and consistency. The site-responsive, intermedia practices of the following artists, which took place after a considerable break, gain more significance when examined against the background of the overtly ideological character of the official post-Revolutionary art and the formalist approach chiefly promoted by the universities’ conservative policy.

Post-Gallery Ventures: Project 71 and Experience 98

In 1992, a group of young painters based in the capital spontaneously gathered together with the idea of turning a whole building into a work of art. Their quest was guided by impulse and apparently not firmly based on any theoretical consideration, but the resulting work might be considered as one of the first confident attempts in the Iranian contemporary art scene to withdraw from galleries and formal art venues to explore concrete sites and at the same time bring forward the idea of “ephemeral art.” The site was a large residential building in Pasdaran, northern Tehran, which had been considered a Kolangi house [16] and was planned to be demolished in a matter of days. In Project 71 (1992), four painters (Mostafa Dashti, Shahrokh Ghiassi(1952-1396), Sassan Nassiri, and Farid Jahangir) [17] worked ceaselessly to turn the entire building into a huge gallery of paintings that were destined to be abolished together with the house. The subjects of the paintings were various, but the idea of destruction and ephemerality prevailed due to the destiny of the project [18]. The artists’ impetuous, unsponsored project was mainly an act of seizing the opportunity of working together in an unrestrained, intuitive manner in a huge space. However, there was an undertone of rebellion against heedless constructions in Tehran in the 1990s. The construction rate in Tehran during those years was moving speedily towards an unconceivable point. Countless yarded houses were demolished to be replaced by high-rise complexes. This process, which defaced the most iconic neighborhoods of Tehran, still continues at a disastrous rate all over the megacity and has resulted in grave depletion of the city’s stylistic variety, cultural memory, and historical texture.

Key figures in the art scene, as well as students and younger people, came to visit [19]. In the restricted atmosphere of the early nineties in Iran, thirteen years after the Revolution and in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war, the highly controlled and scattered art scene of Tehran was greatly encouraged and stimulated by this unconventional event. It should be noted that this rebellion against the formal and commercial venues of art was taking place at a time when the Iranian art market was still small and local. The number of art galleries was limited and the Iranian contemporary art scene had yet to become overtly commercialized. In addition, considering the fact that the group consisted of active painters who did not seem to have a coherent site-specific statement in mind, we might also assume that these early rebellions were largely inspired by Western precedents.

It took six years for the next similar project to take place, when the artists [20] gathered again in Tajrobeh 77(Experience 98) (1998) to transform another old Kolangi house in northern Tehran (near the Hosseinieh Ershad). They were joined by Bita Fayyazi and Khosrow Hassanzadeh, who later become influential in introducing new means and media to the Iranian post-Revolutionary visual art scene. The second project involved bolder interventions, including making cracks and holes in the walls and using mirrors, three-dimensional structures, and other devices to increase visitor interaction. It demonstrated a markedly more informed, developed encounter with the space. The substantially altered residence, covered by paintings, sculptures, and abandoned objects, generated an immersive experience that brought together associations with the site as an abandoned home and the visual impact of the artworks. Installations in every corner of the house invited visitors to roam and feel the unpredictably changing atmosphere, while the destruction of parts of the walls further distorted their sense of orientation. The show was widely visited and Maziar Bahari recorded the event in a documentary titled Honar-e Takhrib (Art of Demolition, 1998).

Actions like these were rare since such projects were by no means easy to undertake. In the politically and economically constrained atmosphere of the 1990s, independent artistic projects were not encouraged in Iran. Complicated bureaucratic and formal procedures were required to gain access to a public space or any official institution to perform a creative event, making it nearly impossible for an independent group of artists to get the required authorization. Non-official sponsors were also yet to be involved in supporting alternative artistic endeavors. Both aforementioned Kolangi projects took advantage of houses belonging to the artists’ relatives. They were occasional chances that provided the artists with the opportunity to take part in a collaborative project in situ and expand their site-consciousness.

I recognize the practices discussed so far as belonging — in Miwon Kwon’s terms — to a phenomenological, experiential paradigm primarily concerned with the physical characteristics of the place and the viewers’ perceptual and bodily encounter with the altered environment [21]. They did not specifically address the context of the site in its social, historical, or other terms. However, even with the absence of any overt socio-political statement, a radical message of freedom and ambition was communicated through their innovative, participatory gesture.

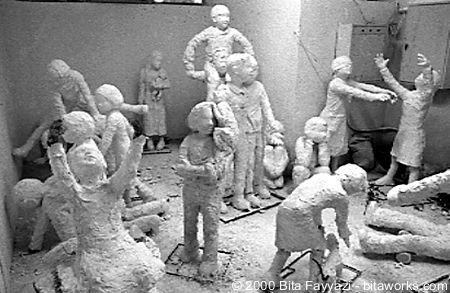

The next project reached greater maturity in terms of both concept and accomplishment. Blue Children, Black Sky (January 1999), held in an old downtown building in Tehran, was the third and last contribution of these artists as one group. Unlike the other two projects, it clearly addressed a specific social issue as its subject matter: the critical air pollution in Tehran, then rated among the world’s most polluted cities. An early example of a post-Revolution multimedia group exhibition, the show centered on the theme of children suffering from the outcomes of air pollution. The site was aptly located in a packed and polluted city-center area(Nejatollahi/Villa Street). The building, which was once owned by a wealthy Zoroastrian businessman, had been confiscated after the Revolution and was lent to the artists for two months by the Municipality of Tehran. In accordance with the central theme, Bita Fayyazi put in the hall fourty cast sculptures of children playing while making ambiguous gestures. The inanimate yet realistic casts imposed an ominous atmosphere, which was heightened by the expressive paintings and collages by Khosrow Hassanzadeh which covered the walls and ceilings, and the life-size photo portraits by Sadegh Tirafkan (1965 –2013) installed in the area around the staircase. In the basement, Maziar Bahari’s installation consisted of hospital beds, above which videos of children suffering from respiratory complications due to air pollution were shown on the monitors.

Organized around a specific subject matter, this show can be seen as moving away from the merely physical, experiential paradigm — which aimed at shocking the audience and making an impact through a phenomenological experience of the overwhelming space — to step into a new, issue-based one which sought to address a tangible social problem. One review of the show commented that “the overall atmosphere of the show and the innovative treatment of space” made up for “the rudimentary character of the sculptures and paintings [22],” which suggests that the works were perceived not as autonomous objects but as acting in the context of the entirety of an event.

Such an appreciation of the totality of an event over its individual components, which was the direct result of this orientation towards the site, had an undertone of challenging the principle of aesthetic autonomy, which in turn brought about a significant change in the new generation’s conception of artistic media. This marked a post-modern replacement of the concept of medium-specificity as the marker of advanced art practice with site-specificity, which revolves around the entirety of an event-site and the visitors’ phenomenological as well as intellectual experience. In the context of such high-profile public exhibitions, the artists were also given a collective voice and the idea of an artistic community began to reappear.

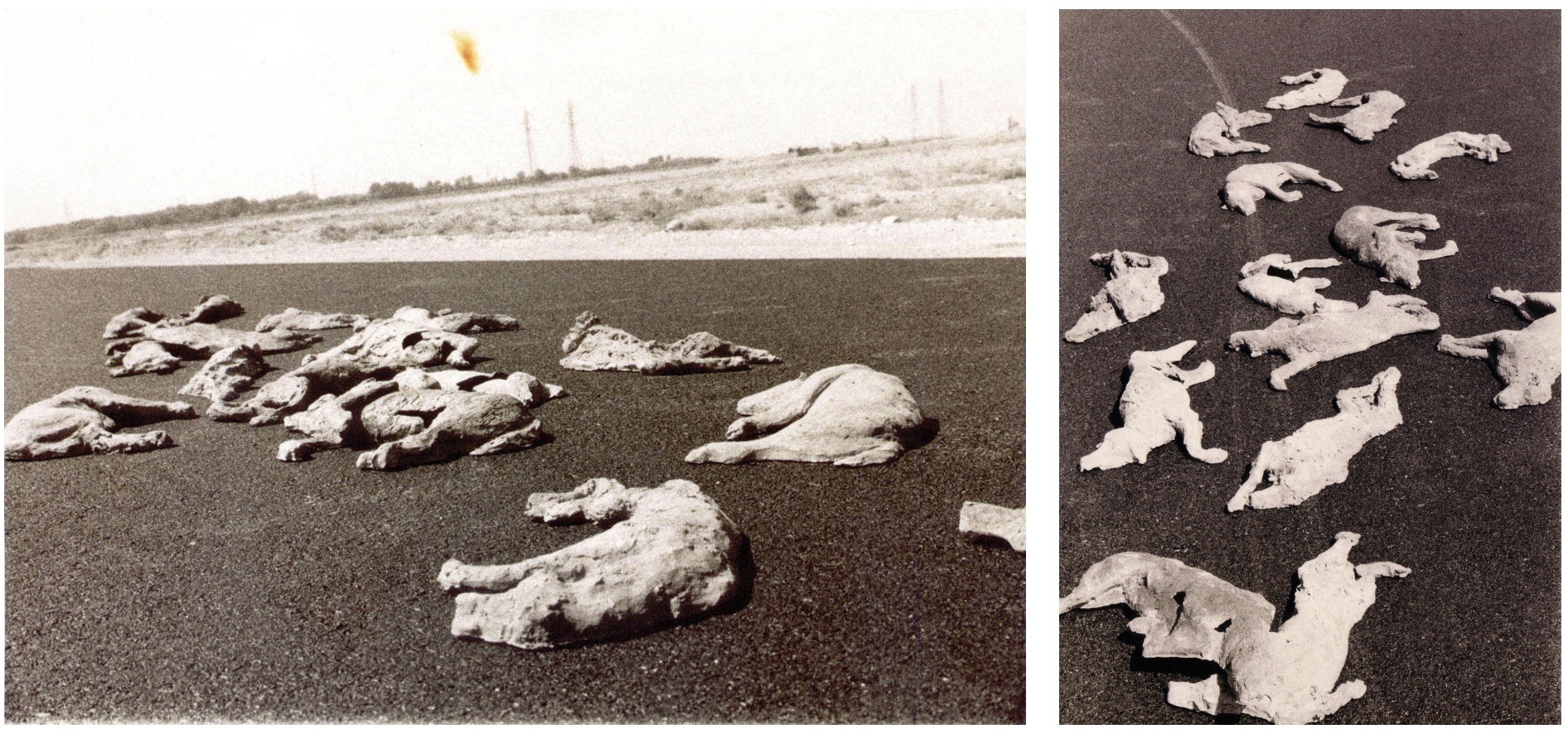

These experiences directed some of the abovementioned artists to their subsequent practices. Notably, in Bita Fayyazi’s work, the site remained an integral element. In 1998, she had already adapted her ceramic practice for a site-specific work in which she made 150 ceramic dead-looking dogs and scattered them on a remote road near Tehran. It was a tribute paid to the thousands of dogs killed in accidents and abandoned to decay on freeways. She subsequently buried the casts in a mass grave in a symbolic gesture to bring to attention the issue of the harsh life and cruel death of street animals which goes unnoticed with no mourning. Some years later, she decided to tour her sculptures around the city in a pickup truck (2003). By holding a mobile exhibition, she sought her audience among random people of the city who had no intention to visit a gallery or participate in an artistic event. This could inspire people other than the usual elite who frequent the art exhibitions.

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art as a Mediator

In the next years, the flexible, experimental approach taken by the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA) played a significant part in the introduction and development of new tendencies in Iranian contemporary art. During the temporary period of political reform (Islahat, the presidency of Moahammad Khatami, 1997-2005), under the direction of Alireza Sami-Azar, TMoCA adopted a daring approach to exhibition and curation which was unprecedented in the period after the Revolution and also different in nature from the carefully programmed events before the Revolution (1977-1979). Between 1998 and 2005, large-scale thematic exhibitions with a free approach to subject and medium were held one after another, all of which were based on open calls and were financially supported by the museum. The reformed atmosphere attracted a large, eager public and brought together the scattered, isolated artists into a consolidated “artists community” [23]. The new prospect helped to introduce and reinforce practices of new artistic media, and the flexible and flowing architecture of the museum, generously offered to the mostly young artists, provided them with an unprecedented opportunity to develop a conscious engagement with the site. The spectacular shows — unparalleled after the Revolution — engaged a new, critical generation of artists, many of whom were eager to take on sociopolitical topics. The museum’s elegant halls and garden were a huge temptation to the new generation of artists who had long seen these spaces being dedicated to official Revolutionary art or socio-politically neutral paintings. I will refer to a few works, among many, that I find more site-conscious, and I will try to show, both here and in some of the subsequent thematic categories, how they challenged the museum site each in their own way.

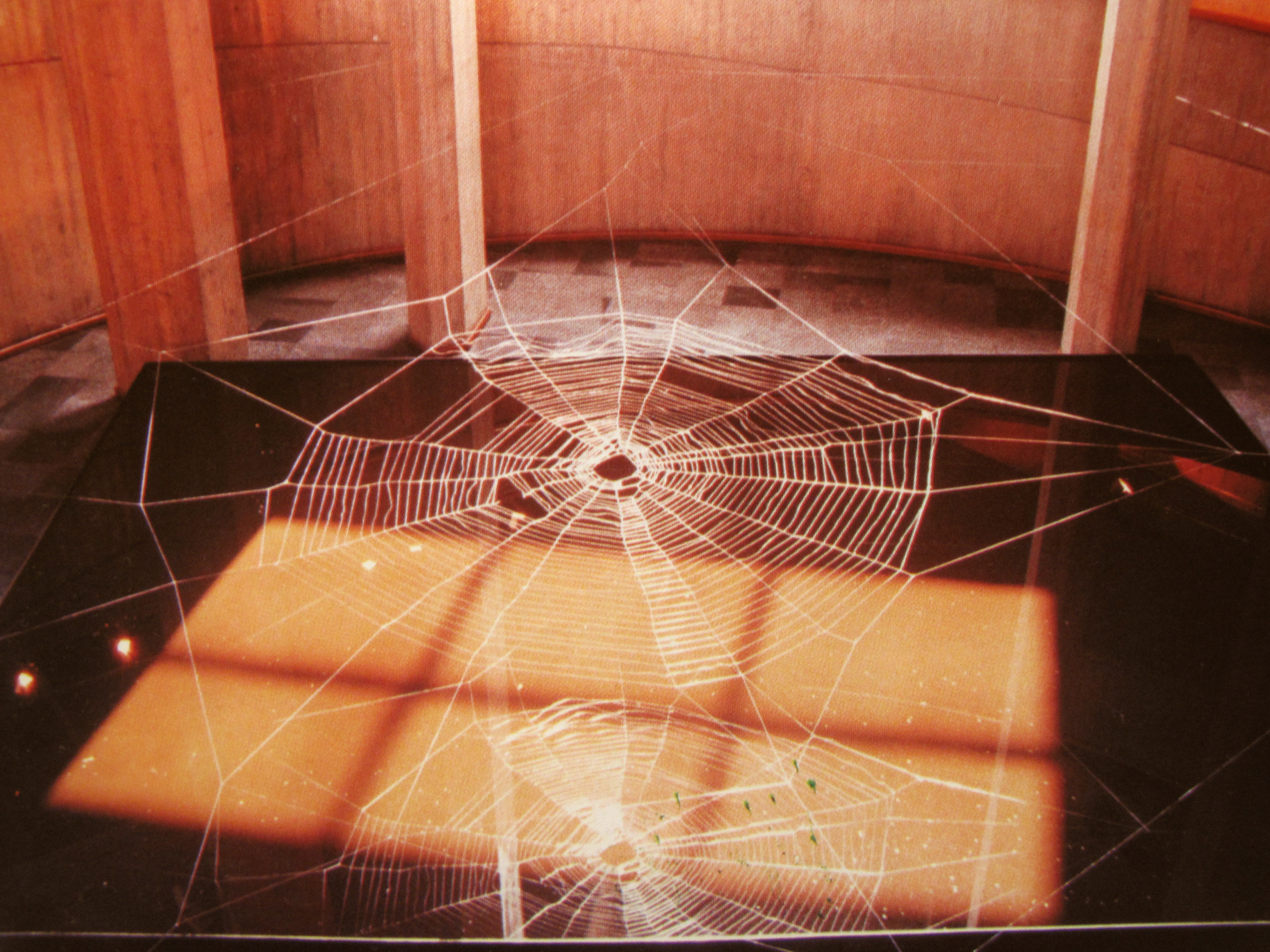

Shahriyar Ahmadi’s Cobweb (2001), made on the occasion of the First New Media Exhibition, was a huge realistic spider web hanging above TMoCA’s central ramp. Made with considerable precision from very thin plastic strings, it glittered gently in natural light. Though almost invisible from afar, it was captivatingly realistic up close and was in perfect unison with the space above the atrium. Formal and spatial characteristics of the surroundings were taken well into account, including the location of Noriyuki Haraguchi’s (1946-2020) piece Matter and Thought (1977) (an oil pool) below the atrium, which reflected the web, and the beam of light entering from the upper square window. The artist adjusted the height of the web and its circular expansion in line with the visitors’ movement on the museum ramp, thus providing a perfect view from every angle. The humble act of quietly transferring a natural spider’s web to a venue of contemporary art, however, had a witty undertone. It referred to the museum’s stagnancy for more than two decades due to the highly ideological post-Revolutionary cultural strategies, which had left it with little vitality and few audiences. The cobweb — a sign of obsolescence and abandonment — could be read as a silent yet powerful statement of the new generation of artists who found themselves alienated by the art that came out of the museum’s previous policies of exclusion and elimination and by the outdated stereotypical attitude which had driven a key, lively institution into the shade.

Some artists extended their interaction with the site beyond the walls of the museum galleries. Amir Mobed’s whimsical outdoor installation during the Second New Art Exhibition comprised 12,000 gypsum mushrooms planted in the sculpture garden of the museum (Mushrooms, 2002). Thousands of white mushrooms appeared overnight to totally transform the familiar look of the garden which is located on Kargar Street, one of the most populated areas in Tehran. People reacted to this event in various ways. Some related it to sudden rain and thunderstorms, school children tried to filch some mushrooms, and employees of the companies overseeing the garden bet on whether they were real or artificial. Many random passers-by and drivers encountered the work without any intention to see art, and numerous people were dragged by curiosity into the museum to eventually visit the exhibition and join the venue’s new, excited audience.

Behind their poetic façade, these works conveyed a potent message. Their modest manner and inobtrusive iconography stood in sharp contrast with the noisy, propagandistic character of the Revolutionary art and the state’s ideological apparatus at large. Against the backdrop of state slogans and the official system of visual signs, the sincere and tangible quality of these works attracted much attention and opened up new perspectives.

Institutional critique

This was how the young non-conforming artists seized the open-call opportunities to create occasional satirical, politically engaged, or anti-institutional art, using the language of irony and metaphor. These statements were ironically made using the official budget of TMoCA. In this way, TMoCA, which had long represented the state’s specific cultural agenda, displayed a shift in its policies toward encouraging social and institutional critique.

One bold instance took place in the Second New Art Exhibition (2002) at TMoCA. The Road Is underConstruction (2002) was a live performance conceived by Mehran Houshyar and directed by Sadegh Safaei (1961-2022), mentioned at the beginning of the essay [24]. A dozen young men and women (mostly art students) with overall costumes and covered faces performed a series of curious acts during the whole course of the opening day. They first blocked the entrance of the museum with barbed wire and stopped the enthusiastic audience from entering the show. Holding signs and placards with slogans such as “The road of art and culture is under construction” as well as traffic signs, they kept the act until the audience became impatient and the security guards, who never had such an experience, were completely confused. Dressed in military-style overalls, the performers treated the audience in a harsh manner. They even taped a few people to the museum railings. Finally, they disappeared and left the confused audience with a few wirecutters, only to reappear inside the entrance and force the visitors to pass through moving frames. Every visitor had to walk, with great difficulty, through the constantly moving wooden frames the performers carried in their hands. Other members of the group, also dressed in overalls with covered faces, strictly banned the people from doing otherwise. They treated the museum director, Alireza Sami Azar, and all the other museum staff in the same way. The venue had not witnessed — and never did afterward — such a bold event, and that’s why the visitors were too overwhelmed to think of any possible dissidence. They tamely obeyed the odd ceremony and entered the show, while the group continued to march through the museum halls waving their paper batons and pretending to overhear and control the visitors and other artists.

The Road Is under Construction used a double-coded scheme to address state repression and the institutional autocracy of the art world at the same time. The costume and gestures, along with the actors’ harsh manner when arresting people and forcing them to go through the “frames,” unmistakably evoked the suppression forces. The signs and slogans were also a clear parody of the prevailing negative official stance towards certain creative arts. On the other hand, the overall idea of taking the site and the opening ceremony under control challenged the institutional framework within which works of art were displayed, valued, marketed, and sold. It may seem surprising that despite the progressive role TMoCA played during the reform period, it was frequently chosen as a target for institutional critique. This might be due to a shortage of active official institutions considered significant and worthy of being challenged by the artists. TMoCA, under Alireza Sami Azar’s management, became an appropriate target, as it was influential and dynamic while also flexible and tolerant. Mehran Houshyar, the art director of the project, later said that they never dreamed that the proposal for this performance would be accepted in the open call [25]. It was, anyway, a short-lived time of tolerance and possibilities.

These few instances evidently suggest the emergence of another paradigm in engaging with the site. While the early endeavors were more concerned with setting up a physical environment than responding to a site’s social and political connotations, these works clearly manifest an awareness of the various contexts that contribute to the significance of a site.

Reclamation of public space

Site-specificity is also known as a device that enables artists to take public spaces out of the institutional command and appropriate them for their own statements. In the summer of 2003, Shahab Fotouhi and Neda Razavipour took on a giant street project which was an example of a large-scale, independent public art project specifically conceived according to the intended site. In Census (2003), for two weeks, seventy huge portraits appeared inside the window frames of the Atisaz residential complex in Tehran which was then under construction. Close-up, full-face portraits of ordinary people of the neighborhood, taken by the photographer Abbas Kosari, were mounted on lightboxes and fixed against the empty windows of the unfinished high-rise building. The close-up portraits were cropped in a way to highlight one’s look and expression and convey a sense of confinement. They lit up and faded away with the rhythm of human breath. Both drivers and pedestrians could view the project which faced both Chamran and Nyayesh Highways. The extensive administrative correspondence behind the work was exhibited concurrently in No. 13 Vanak Gallery, together with a documentary of the viewers’ reactions and questions.

Census addressed, more than anything, the politics of portrait visibility in post-Revolutionary Iran, where numerous surfaces facing the streets and other urban passages are covered with faces of political leaders or martyrs of the Iran-Iraq war. Citizens are surrounded either by these portraits or those of models and celebrities in advertisements, while there are no chances of seeing a real portrait of common people. Censusis thus an attempt to reclaim urban public space by giving visibility to anonymous ordinary citizens while appropriating the same conventional austere style as official full-face portraiture.

Engaging the History of the Site

Aside from limited opportunities offered by TMoCA, few site-related experiments in contemporary Iranian visual art duly addressed the memory or history of the site. This is mainly because artists could only choose venues according to their availability rather than their specific context. Therefore, it is a rare opportunity for an artist to be able to work in a site that one has chosen freely based on its cultural, historical, or political connotation. The strict official administrative policies regulating urban and public spaces are, therefore, a major factor in discouraging artists from interacting with specific urban sites.

On the other hand, the majority of the urban surfaces have already been occupied by state propaganda or advertisements. In some cases, even making photographs from certain public spaces is faced with restrictions, let alone implementing an independent site-specific project. Hooman Mortazavi, one of the founders of Movazi Group — to which I am going to refer — believes that “the choice of location in these projects was more a matter of compulsion rather than decision and choice. It’s more a matter of finding a way to survive and work rather than putting hand on a particular site [26].”

One project that managed to pass this administrative barrier was implemented in December 2006 by Farideh Shahsavarani. I Wrote, You Read (2006) took the huge old building of the popular newspaper Itila’at and covered its vast interior spaces with two tons of newspapers. The immensity of the site made it very difficult to create an immersive atmosphere, and the three video installations put in place could hardly make a significant effect. Two of the videos documented the installation, and the third featured a silhouette of an old woman making her way through crumpled papers using a walking stick. A lack of clear content and frame of reference was evident, as the only issue possibly raised by the whole installation was the enormity of the overwhelming news facing us, while the history of media and newspapers in Iran, including that of Itila’at newspaper, was left untouched. However, this project was one of the few instances where an artwork engaged a site with asignificant history and character.

Manipulating the Cityscape

There are also other urban interventions that were carried out outdoors and sought to encourage their audience to see the cityscape and its components in a new, inspiring new way. Movazi Group came together in 2004 and worked exclusively in public spaces [27]. As suggested by the group’s name (movazi means parallel), they defined their practice as a parallel and alternative move that did not intend to intersect with mainstream art. Since they decided not to seek financial or institutional support of any kind, in order to “make things possible” (the group’s motto), they set to eliminate obstacles including the lack of financial backing. Their funding was limited to the monthly sum collected from the members, and instead of making correspondence with galleries and cultural centers, they moved into streets and other outdoor spaces. Their projects consisted of joyful and unsophisticated interventions in the urban space. Their credo also challenged the authority of a single artist or “creator” by following a certain procedure: after the budget was collected from the members, they selected one work proposal among all, modified it as a group, and implemented it in the form of an urban project. All the works belonged to the entire group, and the only long-lasting output was the documentation of the projects.

The main rationale of the short-lived Movazi Group seems to be, on the one hand, to resist the official art institutions and avoid the complications of the formal art scene, and on the other hand, to take advantage of their collective intellectual and practical force [28]. The group’s low-cost projects included installing hundreds of colored pinwheels on a lawn on the Haqqani Highway, adding a web of balls to a corner of a park, or attaching prayer bands to trees in a public garden. These works were intended to alter the appearance of the city and create a divergent stream from the formal art scene. A few of the projects were interactive while most of them took only the visual aspect into consideration.

The tendency to rebel against formal art spaces and to take an adventure in urban sites soon spread to art students. In 2009, the “Tehran Carnival” group which consisted of six female art students started making experimental group projects in a manner evocative of street art [29]. They made fantasy modifications and temporary installations in different parts of Tehran, including the City Theater area, Darband Mountainside, the University of Art, sides of highways, sidewalks, inside footbridges, and so on. The number of these projects reached more than twenty in less than two years.

The urban interventions by both the Movazi Group and the Tehran Carnival might be considered as belonging to a different experimental paradigm in post-studio, post-gallery practices, which doesn’t comprise engagement with specific issue-based or discursive content but is marked by relying on the inherent potentialities of the urban space and attempting to surprise and engage the audience, this time with whimsical, fanciful ideas. They mainly seek to dispose of the barriers and complications of the formal art world and at the same time challenge the urban surroundings. Their works hover between fine arts and street art, as they contain some of the characteristics of both models. Their spontaneous approach which did not seek to be licensed and/or sponsored, together with their direct interaction with the city space, is similar to the pattern of street art, while the fact that they are contemporary artists who once studied art, frequented art galleries and artistic communities, and got inspired by ideas shared in the global contemporary art community connects them to the art world.

The works discussed here provide a few examples of a general shift towards various post-studio, post-gallery practices in the art world of Tehran during the 1990s and the 2000s, a period of transition. The change was short-lived. Following the establishment of a new art market, a major part of the art scene redirected its energy towards making more marketable works of art. In this essay, I have identified two main paradigms in the above-mentioned site-conscious practices, one mainly experiential and phenomenological, which is generally based on the physical potential of the site and concerned with the visitor’s visual and bodily experience, and the other an issue-based, socially engaged approach which seeks to take advantage of the site to convey a message. Some key strategies might be identified in this regard, including seeking new momentum in alternative venues, reclaiming public spaces, creating a situation for the visitors’ perceptual and bodily experience, manipulating the cityscape, and finally, practicing institutional critique. There are not, of course, any clear boundaries between these strategies but only a matter of focus. The young artists whose works have been discussed in this essay have had various careers, but many of them continue to experiment with new media and approaches, which has changed the overall character of the Iranian contemporary art scene in recent years.

Helia Darabi (born 1974, Tehran) is an independent art historian based in Tehran. She is a Ph.D. in Art Research from the University of Art in Tehran and has been writing essays and critiques on contemporary Iranian art since 2000. She has been teaching critical courses on themes and approaches of contemporary art in various universities and institutions in Iran since 2008.

[1] Miwon Kwon, “One place after another: notes of site-specificity,” October, vol. 80, Spring 1997.

[2] Nick Kaye, Site-Specific Art, Performance, Place and Documentation (London and New York, Routledge, 2000), p.1

[3] Ibid, p.4.

[4] To provide a more accurate description of specific works, many other related terms have been developed by scholars, including site-determined, site-conscious, site-oriented, site-referenced, site-responsive, site-related, etc.

[5] “Installation” is the noun form of the verb “to install,” the functional movement of placing the work of art in the “neutral” void of a gallery or a museum. Unlike earthworks, it initially focused on institutional art spaces and public spaces that could be altered through “installation” as an action. “To install” is a process that must take place each time an exhibition is mounted; “installation” is the art form that takes note of the perimeters of that space and reconfigures it. Erika Suderburg, Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art, University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 6.

[6] Rouyin Pakkbaz, Painting in Iran, From The Ancient Times to Today (Zarrin o Simin Publishers, Tehran, 2000), p. 206.

[7] See also: Richard Ettinghausen and Ehsan Yarshater, Highlights of Persian Art (Westview Press, 1979) and Hamid Keshmirshekan, Contemporary Iranian Art: New Perspectives (Saqi Books, 2014).

[8] T. Rezaei, “The catalyst of Iranian Artistic Movements in Iran” (in Persian), Tandis, No. 113 (November 2007), p. 9.

[9] Shahrooz Mohajer, Interview with Kamran Diba (in Persian), Golestaneh Magazine, No. 109 (November 2010), p. 20.

[10] Parviz Tanavoli’s forward to the Exhibition: “Women Wearing Shoes”, 1976.

[11] Written in Nasta’liq calligraphy on the paintings, Man Abbaz e Zebardasti hastam means “I effortlessly float on water”.

[12] Marcos was the founder of “Aesthetic Gallery” in 1954, one of the pioneer art galleries in the country, andhe was also the main figure behind launching the First Biennial of Contemporary Iranian Painting in 1958.

[13] “Azad Group’s Domestic avant-gardism” (in Persian), Iran Newspaper, No. 2118 (May 7, 2002).

[14] “My Roots Are All Here”, Interview with Gholam Hossein Nami (in Persian), Shargh Newspaper, No. 1272 (June 18, 2011).

[15] Both gestures have a remarkable dissident tone. I have no evidence, however, that there have been meaningful ties between these works and the concurrent political unrest. Momayez writes in the catalogue of the exhibition: “I have always had a covert fear of knives; and I tried to demonstrate that experience in the forms of a rain of knives, or ‘the Sword of Damocles.’”

[16] “Kolangi” (literally “good for pickaxe”) is a popular term applied to residential buildings with a large yard and two or three stories, which are targets of demolishment and are substituted for a high-rise building, even though they are not actually time-worn.

[17] They called themselves “the free studio of contemporary art,” an initiative which soon fell apart due to Shahrokh Ghiassi’s sudden death in a movie backstage accident.

[18] From the author’s interview with Sassan Nassiri, 2019.

[19] From the author’s interview with Mostafa Dashti, December 2011.

[20] Farid Jahangir, Sassan Nassiri, Mostafa Dashti, and Ata Hasheminejad.

[21] See Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-specific Art and Locational Identity (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002).

[22] Excerpt from a critique by Ali Shir Mohammadi, Tavous, No. 2 (Winter 2000).

[23] For a more detailed account of TMoCA’s activities in this period, see Helia Darabi, “Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art as a Microcosm of the Administrative Cultural Agenda,” in Regional vis-à-vis Global Discourses: Contemporary Art from the Middle East, University of London (SOAS), 5-6 July 2013.

[24] The Road is under Construction (2002) was a work by Mehran Houshyar, directed by Sadegh Safaei. Actors included: Hamid Dadashi, Raha Nourmohammadi, Houman Shabahang, Nazanin Keshavarz Sadr, Pouman Shabahang, Vida Daneshmand, Vahid Nafar, Kamyar Ebrahimi, Arash Raeisi and Reza Vojdani. Second New Art Exhibition, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, 2002.

[25] From the author’s interview with Mehran Houshyar, July 2021.

[26] From the author’s interview with Houman Mortazavi, January 2011.

[27] Some members of the group include Hooman Mortazavi, Naghmeh Ghassemlou, Mohammad Hamzeh, Neda Razavipour, Javid Ramezani, and Mehrova Arvin.

[28] From author’s Interview with Hooman Mortazavi, January 2011.

[29] Sepideh Zamani, Ayda Alizade, Mahtab Alizade, Elnaz Ezati, Elmira, and Elmira Yousefi, all BFA students of sculpture at the University of Art, Tehran.