An Interview with Shmuel Gonzalez

By John Hulsey

In this interview, artist and filmmaker John Hulsey speaks with Shmuel Gonzalez, an “unofficial historian” of Boyle Heights. Their conversation took place outside of the Breed Street Shul, an Orthodox Jewish synagogue and important landmark in the neighborhood. They discuss histories of immigration and political organizing in Boyle Heights, and how these connect with contemporary anti-gentrification struggles. They reflect on the continuity of racist structures of power that have affected the neighborhood, as well as the continuity of resistance movements. In examining why Boyle Heights has become fertile ground for current forms of activism, they suggest that we might look to historical examples in order to create new coalitions and forms of solidarity.

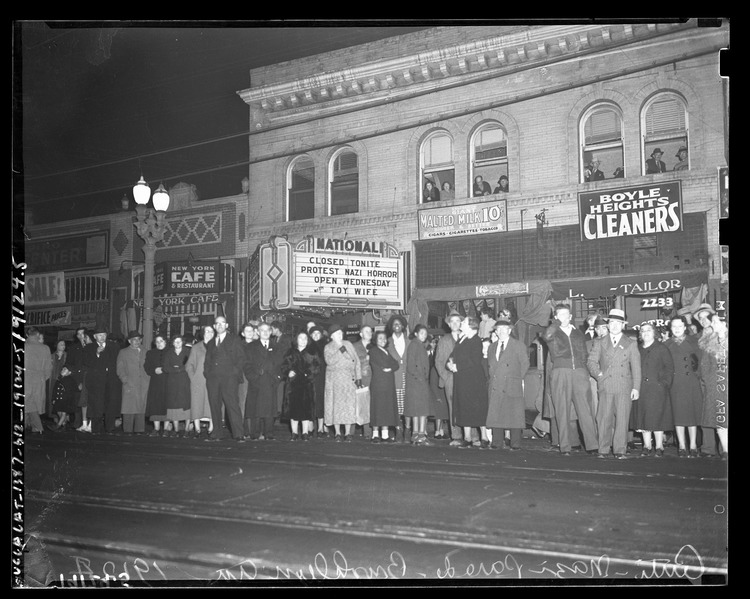

John Hulsey: I thought we could start by talking about this photograph of the anti-Nazi parade…

Shmuel Gonzalez: Yeah, the anti-Nazi parade of November 1938, right after Kristallnacht.

JH: Right. I thought this would be a good place to start, first because it’s your essay on this image that first drew me to your work as Boyle Heights’ unofficial historian, and also because the protest took place right around the corner from where we are right now. What you wrote was especially moving for me. It came at a time when I was trying to sort out my own family story, which had mostly been buried during the period of post-war assimilation, and also because, as an artist, it came at the peak of the art gallery struggle in the neighborhood. It seemed like you were putting your finger on this long history of resistance that we ought to know about.

SG: It’s wild. Boyle Heights is so much in the public discourse these days because we are one of the only neighborhoods in the world that has successfully been able to repel gentrification. We’ve been able to make the case that gentrification is not inevitable. And we’ve been able to create self-determination for the community. This has always been a community of working-class immigrant people who have been sharing with each other their organizational skill.

JH: Can you lay out a bit of the history here? What are the conditions that led to the neighborhood having this robust organizing legacy?

SG: As both a Jewish person and a Latino person, this is very interesting to me. Boyle Heights starts out as one of these communities that’s close to downtown and is initially owned by several large families who have these large ranchos. As Los Angeles starts to grow, it’s one of the first areas outside of the main downtown core to be subdivided into small housing tracts. At the start of the 20th century, it was a pretty fashionable neighborhood: it had beautiful open spaces like Hollenbeck Park, and already in the 1880s and 1890s, there were lines bringing people in from downtown, and that helped develop Boyle Heights.

But at the same time, in the early years, something interesting is happening with the leftover land. Great tracts are being given over to social service organizations that are fulfilling a need for the people of Los Angeles. Specifically, the Los Angeles Orphans Asylum, which was administered through the Catholic Church, and the Hollenbeck Home for The Aged, which was designed for people who would be homeless and destitute otherwise. Then, in the first part of the 20th century, the Jewish community starts establishing their own social services in the neighborhood, starting with the Jewish Orphans’ Home in 1906, making orphans the first Jewish residents of Boyle Heights. The Jewish Home for The Aged opens around 1910 and starts providing homes for senior citizens, and eventually there was even a home for homeless people, the Jewish Wayfarers’ Home.

JH: Can you explain why this became a destination for Jewish immigrants in the first place?

SG: When Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived in the U.S., they found themselves living in cramped and unsanitary conditions in so many industrialized cities. Believe it or not, a lot of people came to California for health reasons. They came for the clean air – which is hard for me to understand, considering I’ve been inhaling smog my entire life! The end of the line was just over here at 1st and Santa Fe. Union station was in our backyard. The first arrivals started writing back to their families: “It’s nice here, there’s industrial jobs, there’s open space, and there’s Jewish life.” By 1916, you get the Breed Street Shul.

JH: Which is where we are right now.

SG: Yeah, I’m always right here right in front of the flagpole!

JH: It’s kind of like your office.

SG: I know, right? Anyway, people who start coming here by choice in the first years ended up getting stuck because of a precipitous rise in white nationalist sentiment. And this happens because of something that occurs right here in Los Angeles, specifically Hollywood: the first full-length feature film in American history, Birth of a Nation, which is basically a story of white supremacy. It shows horrible racist images of Black people in the state legislature eating chicken and standing on desks, and then the “white nights” on horseback – the Ku Klux Klan – coming in as our supposed saviors. As the movie tours, it starts causing riots everywhere it goes.

JH: White nationalist riots?

SG: Yes, and also people of color who were fighting back. There comes a point when people start to say, “You know, we just can’t live with each other. We need to be separate but equal.” You start having people looking at how they’re going to find a legal way to keep races separate, because it’s too explosive to have people living with each other. And white supremacy, with all of its legal might, comes up with the idea of racially restrictive covenants – additional contracts added to the deeds of newly established housing tracts that would restrict who could rent or own property. Then, by the 1930s, when redlining starts, there are designated areas for people of color, where there aren’t these restrictions. These areas are east of the Los Angeles River and south of Adams, creating “East LA” and “South Central Los Angeles,” as we know them today.

JH: How do we get from the formation of the immigrant enclave to a place of political resistance?

SG: Like a lot of immigrant people when they came to America, Eastern European Jews expected that there would be streets of gold. You know, “there’s no cats in America.” You saw An American Tail, right? The reality was that life was really, really hard. People were taken advantage of. They found themselves either homeless or stacked on top of each other in tenements. The work conditions were really what would bring it to a head for Yiddish-speaking people. A major moment was The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, so they started to organize unions on the east coast. Jewish people start to have this ethic of joining unions. In places like Los Angeles, those types of things did not exist at first. They found out the harsh way, very quickly, that Los Angeles was a very conservative and union-busting town. And interestingly for the union movement in Los Angeles, from the very beginning it becomes not just a Jewish struggle, but an international one.

JH: How does that work?

SG: One of the great things about the way people organized in New York City was that union organizers told people to organize in whatever language the workers already spoke. A lot of people who came over couldn’t speak English. Some only spoke Yiddish, and they were allowed to hold meetings in Yiddish. That was the key to getting more members. You had Sephardic Jews organizing people in Spanish. It’s a way of effectively disseminating the union message. And it worked. Things were different in Los Angeles. They said that Los Angeles was “unorganizable.” Rose Pesotta, a Russian-Jewish immigrant and anarchist, requested to start her own independent chapter of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in 1932. She arrives and quickly starts organizing. What’s interesting is that she notices that 80% of the seamstresses in LA are Latina. She understood that she needed to get them to organize, so she starts doing outreach to them, and within one month, she brings 3,000 women into the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, forever changing the inclusion of people of color in the official union structure in Los Angeles. My entire family came out of the United Food and Commercial Workers. And how did we tell our history? It’s because of people like Rose Pesotta who made the unions for the first time accessible to people other than white men.

So Boyle Heights quickly becomes a hub of political organizing and cultural awareness. It becomes notorious. You had the Jewish Baker’s Union 453 who would start organizing in the area. There was the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order and the International Workers Order, one of the biggest Jewish institutions in the first half of the 20th century and an outright communist organization. There was a diversity of ideas here. Even within The Arbiter Ring, the Workman’s Circle, there were six different chapters in Los Angeles, because they all had different opinions on what type of leftists they were.

JH: What were the lines of conflict?

SG: Let me give you an example. They would be right here at the corner at Brooklyn and Soto.

JH: Brooklyn which is now Cesar Chavez?

SG: Right, but we still call it “Brooklyn.” If you don’t call it “Brooklyn,” we assume you’re a foreigner! You’d be here at the corner and people would be talking just like people do today. Today, you go by Ramirez Liquor, you have the old men and women talking about what’s going on in the neighborhood. Over there, in front of King Taco, you have people preaching. That’s the way it was in those days. People would stop, pick up the paper, and talk about immigration, housing costs, police brutality. Sometimes it would get to blows, and then you’d go cool off in the “red corner,” the communist corner over there, or the “black corner,” the anarchist corner over there.

Anyway, inside the Workmen’s Circle, there was a split. There were people who didn’t believe that it was teaching enough about class consciousness. You have to understand that there were a lot of people who came from Russia, Lithuania, and other parts of the Eastern Bloc, and many of them were pro-Soviet, because they felt that the Soviet Union was the only proletariat state. So they splintered off to create the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order and the International Workers Order, which created their own Yiddish schools and became the biggest Yiddish school provider. They also started selling insurance. By the early 1950s, this becomes a huge problem for the entire Jewish community, because the Red Scare has started, and some of the biggest Jewish institutions were actually run by the Reds. The Yiddish camps, the day schools, these types of things.

JH: I remember hearing about these camps growing up because mom went to them. My grandparents sent her there mostly because they were free.

SG: Exactly, that’s how it worked. They were very influential. But because of how much money in insurance these groups had, the State Department and the Justice Department start making the case that if there was a war with the Soviet Union, these institutions would hand over their money to the Soviets. So basically they lift all of the money out of the leftist institutions in Los Angeles. The rest of the Jewish institutions are intimidated into shutting completely. Jack Tenney, who was in charge of the red hunt here, did this through the California State Senate. He was basically California’s McCarthy. And he outright said that Judaism was equal to communism. The Jewish Federation ends up shuttering all of the Jewish Community Centers (JCCs) of Boyle Heights and all of the JCCs in West Adams in order to effectively kill off any meeting places for leftists.

JH: You’ve painted a vivid portrait of what political organizing in Boyle Heights during the pre-war period looked like: labor organizing, communism, anarchism, the yiddishists. Fast forward to today, and the political culture of the neighborhood appears to be shaped by histories of the Chicano student walkouts, immigrant rights struggles, and fights against the construction of freeways, prisons, incinerators, and the demolition of public housing. What do these two histories have to say to each other? Of course in terms of conditions, people then, as today, faced right-wing anti-immigrant sentiment…

SG: It’s funny you should say that, because that’s exactly why I wrote that piece about the anti-Nazi parade. I wrote it before Trump. But I was responding to the Syrian refugee crisis. I was dumbfounded, because the discourse sounded so similar to the one I knew from history. In the Israeli papers, you had a rabbi referring to what’s happening in Syria as a Shoah. Most people don’t remember that Jewish people start getting sent to concentration camps because one undocumented Jewish refugee (who is only undocumented because he has no rights of birthright citizenship in Germany, where he was born), blows away a third-level Nazi secretary. And then all Jews under German occupation become terrorist illegal aliens overnight. It’s just as shocking when we look at the history right here in the US. After Kristallnacht, the US government wouldn’t let European Jews into the country. They were considered racially inferior and unassimilable, and because there’s no way for us to know whether they’re terrorists or spies. It’s just like today, when people can’t come into the country because they’re dope dealers, rapists, gamblers, murderers, or because they don’t keep the Christian Sabbath.

So in November 1938, right here on Brooklyn Avenue, 15,000 people marched in protest of the US government’s policy to exclude Jewish refugees. The US doesn’t enter the war until three years later. People here were well ahead of the times. That’s why it’s important for us now, this side of history, to take seriously refugee crises around the world. When I was researching the Anti-Nazi Parade, one of the things that I was aware of was just how much the tone of white supremacy was coming to the surface today, as it was then.

JH: Can you elaborate?

SG: Here in Los Angeles, Mexicans, Jews, and various other groups were treated differently. They weren’t allowed into many places of business, restaurants, theaters…

JH: You’re talking about the prewar period?

SG: Yeah, and it continues after the war. At first, Jews here realized that as Nazism is starting to rise in the 30s in Germany, you can’t just talk about what’s going on there alone. Some people warned about fascism in the American system, saying, “It could happen here.” But Jewish leftists, and some Anglo leftists, start making the case that it’s not that it could happen here. It has happened here. White supremacy and fascism are manifest through Jim Crow segregation. Which of course has repercussions on immigration and housing. And that’s how coalitions of Jewish people start organizing together with Black people, Mexican people, and Asian people. It’s because they start making the case that we need to fight nationalism, racism, and anti-immigrant policies both domestically and abroad. They realized that the only way that it was going to mean anything to the American people is if we show its ghastly manifestation right here in this country.

JH: I hear you talking about continuity – the groups who are targeted by white supremacy have changed, but the system itself has not. At the same time, I hear the idea of a break – there’s “this side” and “that side” of history, with the moment of transition being the Second World War. Obviously today Boyle Heights is no longer a predominantly Jewish neighborhood…

SG: Right. It’s 98% Mexican-American! It’s staggering. I don’t even think El Paso has it this good.

JH: So let’s talk about this turn from the pre-war to the post-war period.

SG: After the war, people come back to the neighborhood and there’s a big problem. There’s nowhere to go. The big boom of the major highways and the major tract houses doesn’t begin until later in the 1950s. There’s segregation. There isn’t enough housing. The Zoot Suit Riots smashed our belief that we had somehow “fixed” race relations in this country. And so people start to fight over space. At this point, Jews are more likely to be the garment shop owners, not the garment shop workers. And the Jewish community is well aware of how scapegoating works. What can you do in this situation other than address the underlying issue so that it doesn’t become a bigger problem? Eventually, the Jewish community starts throwing its support behind an organization that will become the Mexican NAACP: Community Service Organization, or CSO, which is where you get people like Tony Rios, Fred Ross, and Ed Roybal. Roybal is particularly interesting, because he becomes the first Mexican-American from Los Angeles to represent this district in City Hall. Eventually he becomes the first Mexican-American in Congress, where he starts the Hispanic Caucus. A few days after he wins the election in 1949, he goes to see a house that’s for sale, and the real estate agent tells him: “We’re sorry, but we can’t sell to you because you’re Mexican.” Instead of getting into a fight, he gives the agent his business card and walks away. As he’s getting into his car, the agent notices that the card says “City Councilor.” He runs back to him. “Come back! Maybe we can sell to you after all, if you say that you’re Spanish or Italian.”

JH: Just check a different box?

SG: Exactly. Just check a different box. But Roybal refuses. He takes up the fight against restrictive covenants, and it turns out, after a big survey, that there were only six developers in all of Los Angeles County who wouldn’t discriminate against Mexican-Americans, and there were 11 who would happily lease or sell to Mexican-Americans if they said that they’re Spanish or Italian instead of Mexican. Restrictive covenants are eventually struck down, but here’s the thing: Jews and other people who were able to fit more easily into white society had a much better time getting in through that door. Those who were able to assimilate and become accepted into white society tended to leave the neighborhood. That’s why we call it “following the Joneses.” That’s how two neighborhoods in LA in which Jews were very prominent – Boyle Heights, on the one hand, and South Central, on the other – end up becoming majority Black and Mexican-American communities. It’s because these other groups don’t have such an easy time being welcomed into suburbia because of white supremacy.

JH: I’m still curious about the persistence of Boyle Heights’ identity as a place of political struggle across such a wide span of history, and across so many cultural changes.

SG: Right. So believe it or not, the money that the Jewish Federation used to fund CSO was money that was left over from the anti-Nazi campaign. And of course, out of CSO, you get not just Roybal but Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. From one generation of working-class immigrants to another, people have passed along their knowledge. We are the recipients of a long lineage. That’s why people still refer to Cesar Chavez Avenue as Brooklyn Avenue. We respect Chavez immensely. But the idea is that we’re always connecting our immigrant working-class story to a longer lineage within this neighborhood. As Mexican-Americans, we are picking up this baton that has been passed down to us through many hands and many institutions. We are taking up an oral history that has been retold to us from one generation to the next. Why do I spend time pointing out all these different moments in organizing history? Because they started this organic effect that spiraled into multiple struggles. From labor rights struggles we get antifascist struggles. These turn into civil rights struggles, and out of those emerge the first generation of Mexican-American civil rights leaders like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers. It didn’t just happen in a void. It’s because people chose to build bridges and work together in ways that seem counterintuitive to us at this point of history.

JH: Why is it counterintuitive?

SG: Because our history has been told in a really clear-cut way. “This is the Jewish history.” “This is the Mexican history.” And we’ve been given very easy answers, so that we don’t ever have to deal with the complications and the consequences that come out from them. I feel a responsibility for addressing these issues, as a Mexican-American Jewish person, because when people tell very simple stories, they’re depriving others of the wealth of what we had to do to make this community work. When people are deprived of that, they carry around the mistaken belief that it’s all going to work out on its own.

JH: In looking at how things get passed down intergenerationally and interculturally, we have an opportunity to imagine a more complex vision for the future?

SG: Absolutely. For instance, right now, as gentrifiers start moving into the neighborhood, we can’t make the mistake of thinking that everything will just work out. If we look to history, we see that we need to have a powerful social vision. In the past, they had powerful social apparatuses. They expended great effort to address issues that could come to a head in a community like this, in order to create a community that was functional. “Integration” has always been a struggle. We’ve never achieved it. So the question is: do we really believe that it’s going to happen on its own?

JH: Let’s talk about the current situation.

SG: On the one hand, the new developments pose a threat. On the other hand, I want a community that’s safe for anyone. On this block, there are a lot of African-American families, and I’m nervous when protests against displacement start becoming fights over racial nationalism. I say this because, as a Chicano, we’ve rewritten our own ethno-nationalist story so that we’re no longer the colonists, we’re the natives. You know what I mean? I make a case for Boyle Heights as a place for people who have no other place. At the same time, Boyle Heights is the main hub for Mexican-American people across the country. This is our Vatican City. There is no second for us. If it were to fall, it would be the fall of our civic, cultural, and spiritual home. This is where we learned to be self-aware as a political people. We arise to every challenge on a block-level, as neighbors. Because it’s a very dense community, we have a great word-of-mouth network, and we’re using that to our advantage. We’re proving that gentrification is not inevitable and that it is possible to resist it. But it’s very important, now that we have started to fight back against gentrifying businesses, that we’re able to populate those spaces with something that is useful for our community. It’s important that we use them as spaces of community self-determination, and that we come together in order to build a vision for how we’re going to reinforce and rebuild our community for ourselves.

JH: It seems that the movement against the art galleries in particular has been making both an economic claim as well as a cultural one.

SG: The majority of people in Boyle Heights became aware of the art galleries because of an article that was published in the New York Times. The owner of Maccarone was quoted saying that she was thrilled because of how much money she had to spend on security. To them, it’s still a neighborhood with a bunch of taco stands and collarless dogs. The idea was, “See, these gallery spaces are bringing art and culture to a community in which it’s lacking.” And we were just dumbfounded. You can’t miss the art here because nearly every block has a mural. You see what I mean? You want to talk about a hub of colliding culture…. These people look at our community and to them we’re just like a white gallery wall. Which is galling, because art was so tied to the Chicano Movement. All of the original activists that I knew were artists. The idea of Chicano self-awareness was expressed through the arts. In fact, if you go back to the first big Chicano meeting — held at Camp Hess Kramer, because Rabbi Wolf invited them — that first event, which would later become the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference, was also the first Chicano art show. So in part, that’s what people were protesting. The obscenity of it, the cultural offense.

JH: Given the history of solidarity you describe between many Jews and Mexican-Americans in Boyle Heights, figures like Asher Shalom, whose café was opened to heavy protest, or Moses Kagan, who did his real estate bike tours here, seem like a sad contemporary turn.

SG: Let me tell you when I first became self-aware in this community. I was 12 years old, and it was Christmas Day. I had my first anti-Semitic experience with someone who thought he was being nice to me. I don’t celebrate Christmas, but I had an aunt who lived up in Bakersfield. I was going to go see her for Christmas, because she had no family. So I’m on the bus, and the guy sitting next to me says, “Why aren’t you with your family on Christmas?” So I say, “I don’t celebrate Christmas.” He says “Oh, you must be Jewish.” And then he says: “You know, I have a lot of respect for Jewish people! They own all the houses around here. They also own all the banks and TV stations and media. And, you know, you can’t get anything done in this country without the approval of AIPAC.” This was a senior citizen, a Mexican-American guy, and he thinks he’s giving me a compliment. I sat there and listened to him for a while. I realized that I had heard this over and over again, the story about the evil Jewish absentee landlord. And there’s a history to this. Because of redlining and economic disparity, those who were able to buy up property weren’t willing to give that property up because of how hard they had to work to get it in the first place. You see what I mean? Right at the moment that Jewish people are increasing their ownership, they are starting to move away. People have tended to demonize Jews as the cause of this disparity, when there are many other structural forces at work. Of course, we do have some horrible landlords here. Two blocks away we have Donald Sterling.

JH: Before it gets dark, I thought we could take a moment to talk about one more thing as the sun goes down…

SG: I love this time of day here! If you look over at the Shul, it appears as though it’s illuminated from the inside. But it’s actually the setting sun shining through the windows.

JH: This encapsulates the sentiment I’m hoping to describe. The places you spend so much time studying are both here and not here. The Shul is standing, but it’s boarded up. You said to me once that your friends laugh because you walk around the neighborhood talking to ghosts.

SG: Yeah. It’s especially hard for me looking at this building. I come here with my friend, Irv Weiser, who’s like my father figure. It’s hard to come here with him. We look up at the Shul that his Holocaust-survivor parents raised him in, and we see the razor wire all around it. It wrecks me every time. It is my understanding of history that shapes my sense of obligation in the present. It is this understanding that tells me what I’m expected to live up to in this generation. I haven’t given up on the Shul, just like I haven’t given up on Boyle Heights. There is so much life left in this building if we could only come together to figure it out. There is so much left for us to do.

Shmuel Gonzalez is an activist historian and lay spiritual leader based in Boyle Heights whose projects include Barrio Boychik, Boyle Heights Chavurah, and Boyle Heights History Tours.

John Hulsey is an artist and filmmaker.