Queer Homelessness: Aesthetic, Curatorial and Political Practices at documenta 14

Peter Rehberg

Introduction

My interest in documenta 14 (d14) is at least two-fold: On the one hand, I am a queer theorist who has primarily conducted research in the field of visual culture, including photography, pornography, popular culture, fanzines, and contemporary art. I look at the pictures and objects on display at d14 from this perspective, their politics of representation and their queer aesthetic strategies. On the other hand, my current position as head of collections at Schwules Museum Berlin (gay, or queer museum) puts me in charge of the different collections of our institution, including historical archives, photography, and art collection, and their research. Moreover, I work as curator of both artistic and socio-historical exhibitions. From this viewpoint, I also comment on the history of queer visual culture and archival material, and the curatorial strategies at stake with d14. I used d14 as an analytical focal point in both a graduate course I taught at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2018, and an international conference I organized there. In this line of research, I am interested in the various manifestations of “queer” within a larger post-colonial, anti-neoliberal scope. Having only seen the portion of d14 exhibited in Kassel, I have chosen to focus on the artworks and performances presented there, and will contextualize them with the contributions to the Reader.[1]

I will discuss how the discourse on queerness appeared at d14: as a subject of representation, an artistic practice, a curatorial strategy, as critical and creative writing, and as a commentary on the history of art institutions. In the case of documenta, these themes and practices resonate in specific ways; while “queerness” occupied a central position in the discourse of d14, a closer look at the objects in the exhibitions and the curatorial decisions that were made produces a more ambiguous picture of what “queer” means here. My analysis aims to outline which version of queer d14 emphasized, and at what cost. I argue that d14 came up with its own answer to the disappearance of sexuality in the field of queer studies. d14 makes the sex-positive positions of Annie Sprinkle and Lorenza Böttner accessible through the filter of identity politics, while leaving behind the destabilizing aspects of sex and sexuality—in my mind a central force for the project of queer. This trend became even more visible with the general curatorial direction of the event and its intersectional deployment of a queer critique, already announced through Sprinkle’s eco-sexuality and Böttner’s disability activism. These decisions and their effects also bring to the fore some of the contradictions at work when queer travels from a subcultural space to the public realm created by an institution like documenta. While “queer” gains a broader audience, it does so only in the context of the epistemologies and economies of art institutions, and thus risks losing some of its critical and political power.

Was documenta 14 a queer event? Given the prominence of the term in its various iterations, starting with Adam Szymczyk’s frequent use of “queer” in his introduction to the Reader, to the appointment of queer and trans scholar Paul B. Preciado as curator of the public program and parts of the art exhibit, one might even ask, was documenta 14 the queer event it was promised to be?[2] With the broad scope of references presented at d14, the question about the queerness of this edition of documenta concerns both individual exhibits in specific spaces and the exhibition project spread over the two cities of Athens and Kassel as a whole. It concerns fundamental questions about representation, identity politics, and intersectionality, a critique of capitalism in its neo-liberal fashion, and eventually, it also raises questions about art exhibitions and museums as sites of producing knowledge, and of creating publics. My remarks use a visit in Kassel as a starting point for a broader discussion of queerness at both d14 sites, and in the larger context of some of the current issues in queer studies and theory.

On the level of the exhibits, Neue Galerie in Kassel displayed the work of two artists who were evidently meaningful in a queer context, or even emblematic of the past and present of queer culture: Annie Sprinkle (born 1954) and Lorenza Böttner (1959-1994). Prior to d14, Böttner’s work was relatively unknown to a larger public; it came to documenta through the research of curator Paul B. Preciado. A performance-artist, sex-worker, activist, and scholar, Sprinkle has been an important figure in the history of queer subculture since the 1990s.

Annie Sprinkle: The Theatre of Sex and Eco-Sexuality

Sprinkle, who identifies as a lesbian, became known to a larger public when she toured North American and European cities with her speculum performance on theatre stages. The centerpiece of her show involved using a medical instrument, the speculum, to allow visitors—who would line up in front of her before kneeling down between her legs—a look inside her vagina. Sprinkle’s performances could be read as a parodic literalization of the penetrating male gaze in a heterosexist culture, and in particular, its reproduction in porn. Her work is a deconstruction of the public/private distinction with respect to the female body in patriarchal societies. With this approach she is also a successor to Valie Export’s feminist performances and films of the 1970s.

The visual frenzy of porn has everything to do with the ways women within a phallic economy are forced to “show what they don’t have”—namely, the phallus—thus inaugurating the dynamics of fetishism, voyeurism, and exhibitionism. As Linda Williams observed,[3] in porn the spectator gets to see perspectives and details of the body to which one would never have access during actual sex acts—an important part of Sprinkle’s speculum performance.

Sprinkle’s presence at Kassel was inspired by an excessive playfulness similar to her performances from the 1990s. One room at Neue Galerie was reserved for objects related to her work: photographs, fanzines, videos, plastics, ephemera, and other archival material. The pictures of various sexual scenes starring Sprinkle presented sexuality as a play that allows participants—especially women—to occupy different positions and sexual roles. By stressing the temporal and performative aspect of positions within gender and sexuality as systems of signification, such perspective on sexuality is in line with Judith Butler’s critique of essentialized notions of sexuality and gender.[4] While Butler’s texts were foundational for the field of Gender Studies, their post-structural and psychoanalytic conceptual framework has also been criticized and re-articulated by younger generations of queer scholars since the first publication of Gender Trouble in 1990. The emerging field of affect studies, for example, questions the centrality of desire for psychic and social life, as in Heather Love’s work, while Paul B. Preciado emphasized the limits of the paradigm of performativity when addressing the materiality of the body, especially in the context of trans culture.[5]

Since Gender Trouble, the netporn culture of the 21st century has multiplied the codes of pornographic representation and shifted the fields of alternative pornography as much as its critical reception in queer and porn studies.[6] For this reason, documenting Sprinkle’s work—which, in many ways, can be read as an illustration or confirmation of Butler’s theories—seems somewhat nostalgic in 2017. In their critique of patriarchal power over the female body, Sprinkle’s interventions into pornographic culture appear in a contemporary media context as a commentary about a less mobile, pre-digital mainstream porn culture. This contemporary context would elide her work’s salience as an aesthetic and critical response to the state-of-the-art of porn, shaped by the internet and mobile devices, which creates new forms of production, reception, subjectivity, and community. Not that the forms of power that Sprinkle addresses have magically evaporated with the new millennium, but they have entered into a new era, culturally, technologically, and politically.

Sprinkle’s work, as presented in the room at Neue Galerie, is no longer pornographic avant-garde. Historically, it has lost some of its subversive and critical power.[7] However, by continually de-naturalizing the theatre of sex, Sprinkle has also been named one of the inaugurators of the diversified regimes of pornographic representation. Starting in the 2000s, these have been further developed by some forms of online porn, and are now circulating under the headline “post-porn,” i.e. a form of pornography that at the same time articulates a critique of pornography. With her strategies of female empowerment and theatricality, she became a role model for queering and politicizing porn in the 21st century. From this perspective, displaying her work in 2017 presents a gesture towards acknowledging the genealogy of feminist and queer porn in its different media formats and politics of representation. The room at d14, with its archival material shown in vitrines and on the walls, appears more as a chapter from a history of queer sexuality (focusing on Sprinkle’s work in the 1990s), than a commentary on contemporary pornographic culture. More than presenting a new position of queer sexuality and media culture, it anchored the claim for queerness within a feminist, queer, and pornographic tradition.

To be fair, the relative tameness of Sprinkle’s work at d14 is due not only to the historical distance of her feminist and queer porn project, but also to the medium in which she mostly works. Performance art has always had a central position in Sprinkle’s work, which she maintained throughout the 2000s and 2010s. To translate this format into visual documentation is always a challenge (or disappointment). Next to the room in Neue Galerie in Kassel, Sprinkle was also present at d14 through a series of performances and activities beyond the confinements of the museum space. The Athens part of d14 showed a piece in which Sprinkle and her partner Beth Stephens shared a bed with a third person. The performance kicked-off with Paul Preciado joining them in the sheets. Subsequently, visitors could sign up to take his position in the threesome. “Cuddling Athens” was a variation of the performance “Dirt Bed,” a project that extends the non-binary logic of queer to environmental issues—from making love to humans to directing one’s desire towards plants —that has been shown in various constellations by Sprinkle and Stephens since the early 2010s. In Kassel, Sprinkle, together again with Stephens, presented her eco-sexual approach to the public at walks that included embracing the 7000 oaks once planted there by Joseph Beuys, first publicly presented in 1982 at documenta 7. In this way, Sprinkle’s appearance at d14 was also reminiscent of d13 and its focus on ecology. With another project, she stayed closer to her 1990s performances on sexuality. In Kassel, as well as in Athens, Sprinkle and Stephens offered a “Free Sidewalk Sex Clinic”, a gathering of all kinds of experts to give sex advice.

Sprinkle’s and Stephens’ various contributions to d14 used the rich archive of queer cultural history and its more recent turns, such as queer ecology, to show different representations of feminist and queer subjectivity and community within the museum space and beyond (through participatory approaches). While the concept of queer ecology clearly responded to the contextualization of queer within the programmatic of d14—namely to embrace the flexibility of the term queer for a set of different intersecting issues: ecological, post-colonial, anti-racist, and so forth—the documentation of Sprinkle’s activities as sex worker and performer gave testimony to the emergence of queer out of sexual cultures in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the context of d14, Sprinkle’s and Stephens’ contributions were significant, because, while the term “queer” was omnipresent in Athens and in Kassel, the sexual or pornographic reference to it was much less so. While in some ways Sprinkle as the mother of post-porn was a safe choice for d14—the provocation of her sex-positive-approach no longer risky—at the same time, her presence in this context guaranteed the sexual and pornographic reference of queer would be made visible. Queer sexuality and pornography entered the d14 exhibition space as a question from the past.

Lorenza Böttner: Trans- and Crip-Subjectivity

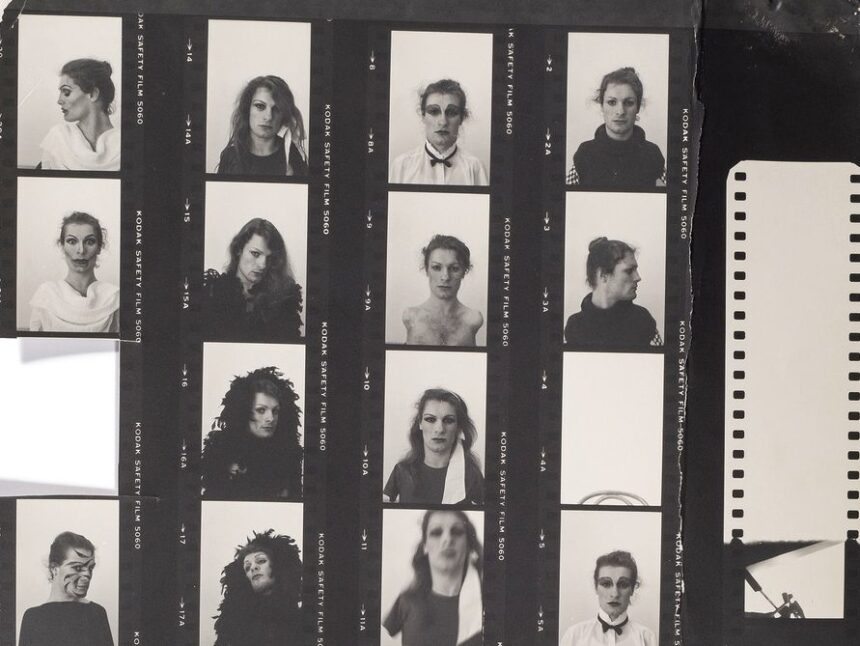

The second significant example of queerness at the Neue Galerie was the work of Lorenza Böttner (1959-1994). Böttner was born into a German family in Chile, where she was assigned the male gender at birth. In an accident in her childhood, Böttner lost both arms and subsequently moved with her family to Germany, where she studied art in Kassel. For Böttner, who learned to paint with her mouth and feet, painting and drawing were also a form of dancing. Her transgressive politics concerned bodily norms of gender and health, but also forms of art production. She was represented at d14 through a series of paintings, drawings, and photographs. Most of Böttner’s works are realistic self-portraits. With the focus on the face and the body, these representations, like her photographic self-portraits, are framed by the binary oppositions of male and female, and able and disabled, a system of signification Böttner worked to unsettle politically. As she did not start a process of bodily transition by taking hormones and did not decide to undergo gender reassignment surgery, Böttner performs male femininity in most of her pictures. Her resistance to body normativity concerns her status as both trans and crip subject. She refused to wear prostheses in the place of her lost arms but instead wore dresses that fit the shape of her body. Femininity and fashion were also important elements of her dance performances in the 1980s, which worked against the desexualization of disabled bodies, as did some of the nude photographs of her.[8]

The important question concerning Böttner’s artistic work as a trans and crip subject is how it relates to the regime of the normal that has historically pathologized and scandalized the position of trans and crip people, for example, in Freak Shows which made a spectacle out of mouth and feet artists. In medicine, too, trans and crip bodies were made hyper visible. Does artistic authorship as a strategy of self-empowerment guarantee an escape from the pathologizing gaze? How effective is Böttner’s form of self-exposure (or self-objectification?) as a resistance to body-normativity and the assumptions about morphology on which our knowledge about gender, sexuality, and health are based?

A part of Böttner’s strategies of self-empowerment consists of representing figures from ancient mythology and art history. She appears as Icarus or Bacchus, thus placing the specificity of her morphology into the context of a classical narrative. Some of the pictures of her upper body without arms make her appear like an ancient bust, the aesthetic authority of which is not diminished but emphasized by the “incompleteness” of her torso. For Preciado, who, after d14, also curated solo shows of Böttner’s work in Barcelona and Stuttgart, Böttner transformed herself into a living political sculpture, thus giving us an alternative answer to questions about what type of queer body we take for granted as a political subject.[9]

The achievement of Böttner’s work and Preciado’s curatorial decision to have it included in d14 is to have disability represented as part of the project of queer; here Preciado follows a movement that since the mid-1990s developed the project of disability studies in dialogue with the field of queer studies. I am highly sympathetic with Böttner’s and Preciado’s approach to articulating a critique of the normal that is both more encompassing (beyond minorities of gender and sexuality) and more radical (extending the question of body normativity beyond gender to ability/disability). I wonder, though, whether the significance that Preciado ascribes to Böttner’s work—namely, to posit the queer body of the crip/trans position as a new political subject—manifests itself in the context of d14. What were the effects of making Böttner’s work and her body visible in Neue Galerie?

The aesthetic strategies in the case of Böttner were not unlike the ones in the case of Sprinkle; in both bodies of work—consisting mostly of photographic or photo-realistic imagery—the goal was to appropriate the spectacle of displaying the female body, the lesbian body, the trans body, the disabled body, and reclaim it as a queer subject position. As opposed to being on display as objects in a misogynist, ableist culture the feminine lesbian subject and the disabled trans subject, here, presented themselves as subjects. They took authorship in their own representations. To be sure, these politics of visibility and empowerment are necessary within a social and political context in which participation hinges on representation. At the same time, they present a certain risk. Visibility does not only create recognizability; the question remains how Sprinkle’s witty exhibitionism or Böttner’s powerful variations of self-representation might unwillingly collaborate with the exploitative, normative regimes of representation that they intend to attack.

Here, context matters. When Sprinkle toured Germany in the 1990s, for example, she showed her performance on the stage of the gay-owned Schmidt’s theatre in Hamburg, which grew out of the LGBT-movement, while Böttner’s pictures were displayed in LGBT community centers or in a context related to disability-activism. While within an LGBTQ environment Sprinkle’s or Böttner’s self-objectification opens the possibility for subjective empowerment, their reemergence 25 years later in the space of a museum during d14 raises questions about how these subcultural aesthetic and political strategies function within an institutional logic of producing meaning. Do these artworks interrupt, or indeed queer the narrative of d14? Or, do they turn into spectacles of “otherness”, this time not within the history of entertainment culture, freak shows, or medicine, but in the context of contemporary art?

Political art in large-scale exhibitions creates a form of mistrust. Even a project like documenta, which since its emergence in the 1950s in post-fascist Europe has had a political self-understanding and educational mission, is not exempt from this logic. At best, this leads to an unresolvable contradiction between the project of queer as a radical critique of regimes of the normal and the art institution—in this case documenta—which with its public funding, budget decisions and marketing strategies, is subject to forms of normalization that also include continual processes of othering.

If we understand queer along the lines of its historical origin as a form of political activism, theory, and art, emerging in North America as a reaction to the AIDS crisis around 1990, and referring first and foremost to sexual and gender minorities (a focus that shifted in the 2000s and 2010s), queerness at Kassel was in fact quite limited. Beyond the obvious examples of Sprinkle and Böttner, there were not many material traces of queer.[10] Noticeably, queer in the sense of a gay male culture was not part of d14. In this way d14 followed a trend that can be observed in academia at least since the 2000s: while the question of sexuality and desire is disappearing from the queer horizon, other social issues have come to the fore. While I do not question the urgency of a queer of color and a trans critique, I am concerned about dynamics that lead to the absence of sexuality in the discourse on queer.[11] In my mind, this tendency has less to do with the increasingly equal legal status of lesbians and gays in Western societies (which consequently would make queer sexual emancipation less of a pressing issue), or with the totality of a pharmocopornographic regime in which sexuality has lost its critical force.[12] Instead, this problem has everything to do with the difficult status of sexuality as an object of study and as a reference point for political activism, in distinction to social issues that can be addressed uncontested in the format of identity politics within a larger culture of queer respectability.[13]

This conflict should not be addressed as a competition between different forms of minority cultures, a battle over the question of who owns queer. On the contrary, their specificity must be acknowledged.[14] More importantly even, the potential of each subculture should be taken into account, not only with respect to the imperative of its representation, but also insofar as it offers us insights into forms of subjectivity and community beyond representation, thus addressing the violence of identity politics themselves and defying the misunderstanding that the project of queer, culturally, theoretically, and politically, can be reduced to identity politics.[15] This is one of the reasons the study of sexuality remains crucial for a queer project.

While sexuality and gender were thematized with Sprinkle’s and Böttner’s contributions to d14, their aesthetics of evidence also limited their queer critical impact in that respect. Their aesthetic and political strategy was to appropriate authorship as a response to a long tradition of pathologizing and othering queer and female bodies. While thus achieving social recognition, they also submitted to the imperative of visibility and its epistemologies, as opposed to an uncertainty of perception and ontology.[16] Didactically, they turned into illustrations of queer culture. This became especially clear in relation to the work of Paul B. Preciado, who as curator brought them to d14.

Paul B. Preciado: Curatorial Decisions and Textual Strategies

As the examples of Sprinkle’s eco-sexuality and Böttner’s disability activism also already show, d14 encouraged us to approach the question of queer in a larger context by incorporating shifts to forms of otherness beyond gender and sexuality. In this sense, “queer” did in fact occupy a prominent place within its conceptual framework. While this is already clear in Adam Szymczyk’s introduction to the Reader, Paul B. Preciado’s participation in curating the public program and parts of the exhibitions gave queerness a public voice and face at documenta 14. Preciado was in charge of the public program “Parliament of Bodies,” and he curated the Böttner and Sprinkle sections. He also contributed essays to the Reader and to the Daybook. The queer perspectives represented with Sprinkle and Böttner at d14—pornography and trans culture—are also the most important themes in Preciado’s own writing project. To an academic, queer and trans audience Preciado has been familiar for quite some time. His book Testo Junkie (Engl. 2013) combines feminist, queer, poststructuralist, and Deleuzian theory with an analysis of medical history and auto-ethnography—his diary of taking testosterone while transitioning.

Preciado should not only be discussed as delivering the queer conceptual context for d14; through his archival, curatorial and writing strategies, he contributed to d14 in various ways. His engagement merges the theoretical, the curatorial, and the artistic. Like in parts of Testo Junkie, in Preciado’s contribution to the Reader, a narrative “I” reports from a trans perspective. Here, Preciado continues a tradition of postmodern writing and theory, as for example in the works of Roland Barthes or, closer to Preciado’s project, Avital Ronell, that has an investment in transitioning from conceptual to essayistic and narrative work, a blend of styles and writing positions that is also characteristic of the literature of the New Narrative. His contribution might be seen as much as an artistic intervention as a critical one.[17] He is not just the curator responsible for giving Böttner and Sprinkle a public stage at d14 but claims for himself an artistic position in this context; a transgression of genres and forms of knowledge that in itself appears as queer.

Interestingly, Preciado’s own contribution proves to be more radical than that which was represented by the artwork he chose for d14. In his deployment of queer, he is much more ambitious than presenting canonical works of queer culture or missing representations of minority positions. Preciado experiments with forms of writing and pushes conceptual lines of thinking to their limits. There is an intellectual radicality to his work that reaches back to a history of queer sex positive writings.[18] He reactivates the conceptual and ontological instability attached to the term queer before it turned into a somewhat lazy marker of identity politics.

If we understand queerness as that which not only shifts, but more fundamentally defies regimes of representation, this potential of queer does not itself materialize with the artists chosen for d14. One way of putting this would be to say, Sprinkle’s and Böttner’s pictures are thematically queer but aesthetically not. They are photographs or realistic drawings that function as illustrations of an idea of queerness, but they are not queer artwork. Preciado’s radical perspective of a queerness beyond identity politics is not mirrored in these two queer positions. This is one of the disappointments of d14: while theoretically specified through the texts of the Reader, I have not experienced this dimension of queer—a fundamental homelessness—with those exhibits that thematically occupy the position of queer.

In his writings, Preciado takes the metaphor of “journey” seriously and thinks of the trans subject’s rejection of an assigned gender position as a movement not necessarily to a certain destination that, once again, can be identified within the binary logic of gender ideology: “I am then not transitioning from femininity into masculinity but from the actual pharmacopornographic regime into an unknown land.”[19] In the first place, trans marks the process of transitioning that defies the stability of biopower as implemented by state politics. Preciado himself experiences this, for example, when crossing borders, as he often did in preparation for d14. The female gender still documented in his passport would not smoothly match with his appearance in front of a guard at the border. Even if he has no personal or political interest in passing as either male or female, the situation at the border demands of the subject to unambiguously inhabit a gender position. In relation to the apparatuses of governance, police, and medicine, trans occupies a non-place that always risks the lack of recognizability and cultural unintelligibility: “transitioning triggers an epistemic crisis.”[20] It is precisely in this sense that the existence of trans, while being socially highly vulnerable, for Preciado, must be claimed culturally and politically. In the larger context of d14 and its play with didactic forms and their undoing—as also exemplified by the “Parliament of Bodies” as a non-formalized form of teaching and learning that is only temporarily institutionalized by the event of d14— Preciado’s project appears as a queer way of unlearning; or rather: queering is unlearning. It is from this position that he is also extending the horizon of queerness. In this line of thinking, Sprinkle and Böttner belong to a didactical program, a way of learning and not unlearning.[21]

Like Sprinkle’s and Böttner’s intersectional projects, eco-feminism and trans- and crip-activism, Preciado encourages us to conceive of queerness beyond sexual and gender positions. At the core of his thinking for d14, that also returns in his most recent publication, the collection of essays An Apartment on Uranus,[22] he establishes an analogy between the trans and the migrant subject. In his text, Preciado suggests that the migrant, when having left her home without guarantee for a safe destination, has a similarly precarious biopolitical, existential, and epistemological status as the trans subject.[23] For him, both migrant and trans are nomadic subjects, or what Szymczyk calls “radical subjectivities.”[24] In this narrative, the queerness of trans and migration stems from the existence in a non-place, a fundamental homelessness, that cannot be redeemed through identity politics. This is not a story of playful destabilization, but an existential non-belonging. It is this site beyond recognition that must be taken into account when we talk about “queer.”

However, there is also a limit to the analogy of the trans and the migrant subject. The trans subject, at least as Preciado describes it, still has the possibility of passing, i.e. to negotiate its status of “homelessness” when faced with state authorities. While the discrepancy between legal document and gender identification exemplifies the violence of state power, the trans subject does not lose their status as a legal citizen, for example, of a country in the European Union. The migrant who must leave her country because of discrimination, violence, war, or famine might have a form of citizenship, but it does not offer protection and rights and, before asylum would be granted, she has no legal status in the country of destination. She might also never reach a “destination.” Given these differences, on a certain level, the parallel between an existence in a refugee camp and the existence in a body marked as trans is only metaphorical. Applying the term queer for both situations risks blurring fundamental differences.

The—somewhat false—analogy between trans and migrant, moreover, also points towards a difference between political, aesthetic, and theoretical discourse that d14 in keeping with post-structural theory actively aimed to undo. While aesthetically and theoretically the homelessness of the queer or migrant subject opens up formal and conceptual possibilities beyond regimes of representation and thought, and invites us to re-imagine the conditions of our existence, for a social and political existence, it primarily represents a form of existential threat and vulnerability.

What is necessary for art and theory not to turn into a one-dimensional aesthetics or a theory of evidence, a simplistic didactic as opposed to, for example, a pedagogy of pleasure and unlearning, cannot be translated directly into the realm of social and political life. Paradoxically, while art and theory should account for the (queer) homelessness of existence, political and social justice depend on an epistemology of recognition. Are these two different demands for queerness irreconcilable? How this tension can be negotiated without establishing a romantic vision of the political, or, on the other hand, a reductive understanding of theory and art, or, eventually, a cynical and conservative division of labor between politics and culture, but rather a dynamic dialogue, exchange and critical relationship between the two, touches upon some of the fundamental questions of aesthetics and political theory. Preciado addresses this problem in two different ways: on the one hand, he performs “radical subjectivity” in his auto-biographical, auto-ethnographical, or auto-fictional writing. On the other, he has a vision of a political transformation through new forms of collectivity and solidarity. One manifestation of this utopian form of being together was “The Parliament of Bodies.”

Queering the Museum / the Institution

“The Parliament of Bodies” was one of the attempts at d14 to create a collective beyond queer identity politics and to destabilize the dispositive of the museum as a public site of knowledge production. A related event that intended to unsettle the stability of the show and redefine the limits of the museum was Annie Sprinkle’s and Beth Stephens’ “Free Sidewalk Sex Clinic.” Both are examples of a tendency towards “curating everything” and de-aesthetizicing art. These participatory practices are responding in different ways to what Tony Bennett in the Reader calls with respect to the institution of the museum “The Exhibitionary Complex.”[25] Talking about the “museum” with reference to d14 is of course not fully accurate. Documenta is a reoccurring series of exhibitions that makes temporary use of the museum space. To this extent, it would be more apt to talk about it only as an “institution.” However, many of the points addressed in the discourse on the museum are also at stake with documenta and its most recent installment d14.

As Tony Bennett following Douglas Crimp’s Foucauldian reading suggested, we should understand the museum as it emerged in 18th and 19th century European societies as an institution at the nexus of knowledge and power. While Foucault himself never wrote about the museum, Crimp and Bennett encourage us to think about it in those terms that Foucault used in his analyses of the school, the asylum, the prison, and the hospital—spatial confinements that through discipline (or control) produce the modern subject. From this perspective, the visit to a museum turns into a lesson, for example, of how to behave within a class society. The respectful silence within the museum’s space and the contemplative position in front of the artwork are part of both an aesthetic and a social training.

If we turn our gaze towards the works of art themselves however, the analogy with the prison or the hospital seems less convincing. If the institutions of the 18th and 19th centuries can be characterized by their confinement of subjects that previously enjoyed moving freely (based on normative categories and thus executing forms of epistemic violence followed by physical violence) —the madman, the prisoner—this cannot be said about works of art as objects on display in the space of the museum. They are not being locked up after having been in the open before. Bennett points out the strangeness of this comparison:

The suggestion that they should be construed as institutions of confinement is curious. It seems to imply that works of art had previously wandered through the streets of Europe like the ships of fools in Foucault’s Madness and Civilization.[26]

Rather, from private collections only accessible to aristocrats, artwork has been made accessible at the museum to a larger public—first and foremost to the bourgeoisie. Herein lies one of the fundamental, historical ambivalences of the museum: while sharing the school’s or the asylum’s power of producing docile subjects, it also democratizes art and aesthetic experience.

This contradictory mechanism helps us, once again, to grasp the positions of Böttner and Sprinkle in the context of d14: the political importance of becoming publicly available through the museum is compromised by the demand of recognizability when presented to a general public. Both artists, with their aesthetics of visibility, do not challenge these effects of musealization. Quite to the contrary, they claim all too well the space the museum has granted them.

The curatorial ambition of d14, however, was precisely to fight this logic of locking up the artwork, namely by spreading the ethics of “unlearning” —a queer unlearning, or unlearning as queer—and refusing traditional forms of knowledge and orientation that would stabilize the artwork’s position within the exhibition. The queerness of Sprinkle’s and Böttner’s art, somewhat lost by putting them into the museum 25 years after their subcultural glory—i.e. their political power—was supposed to be recuperated by relating to a process of transitioning that concerns the exhibition itself and the institution of the museum itself, as in Sprinkle’s walking tours or Preciado’s “Parliament of Bodies”. If we understand the queerness of d14 along the lines suggested by Preciado as an experience of space and movement that the trans subject and the subject of migration share, the ambition of queering d14 lies precisely in leaving the highly ambivalent effect of the museum: producing visibility while confining the experience of art behind a homelessness of the museum itself,[27] “a documenta nowhere to be found.”[28]

D14 showed the limits of a queer project. These limits are due to institutional effects, the logic of representation, and the divergence between the aesthetic and the political. D14 didn’t redeem these antagonistic forces, but it brought to the fore some of the contradictions that arise when “queer” becomes programmatic. Generously, one might say, in its failures to implement the radicality of queer, documenta 14 demonstrated, once again, the very homelessness of queer.

Peter Rehberg received his PhD from New York University in Germanic Languages and Literatures. His thesis (Lachen Lesen. Zur Komik der Moderne bei Kafka, 2007) approaches the question of laughter in Kafka as a textual phenomenon through the lens of literary theory and psychoanalysis. After graduating from NYU, he worked predominantly in the fields of queer theory, popular culture, and media studies. He has taught and researched at several universities in the US and Germany (Cornell, Northwestern, Brown, and Bonn). In addition to his academic work, he also published three novels (Play, Fag Love, Boymen), worked as an editor for queer magazines, and is a regular contributor to the weekly Der Freitag, where he writes on gender and US politics. He was DAAD Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin from 2011 to 2016. He currently works at Berlin’s Schwules Museum as Head of Collections and Archives.

Notes

[1] I will not comment on the debates around queer in the context of d14 in Athens. I am aware that, here, queerness became a contested territory not just with respect to the relationship between art and theory, but very specifically with respect to local politics and the social and economic situation in Greece after years of the austerity politics demanded by the EU. The arrival of d14—a German institution, after all—in Athens stirred, among other things, a debate around “queer hegemony.” To relate these questions to the points I am discussing is beyond the scope of this article. See also footnote 30.

[2] Apart from Preciado, no other representative from queer theory was included.

[3] Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible’ (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

[4] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York and London: Routledge, 1990).

[5] See for example Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2007); Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era (New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2013).

[6] See for example: Katrien Jacobs, Netporn: DIY Web Culture and Sexual Politics (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007); Feona Attwood (ed.), Porn.com: Making Sense of Online Pornography (New York: Peter Lang, 2010)

[7] For a discussion of some of the positions within the culture of post-porn of the 2000s, see for example Tim Stüttgen (ed.), Post / Porn / Politics (Berlin: b_books, 2010).

[8] See this video-lecture on Böttner that Paul B. Preciado gave in one of Jack Halberstam’s classes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwvS-FprT9o. Website accessed, June 1, 2020.

[9] This argument is made in Preciado’s video-lecture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwvS-FprT9o. Website accessed, June 1, 2020.

[10] Another example was Ashley Hans Scheirl’s work. Documenta 14: Daybook (Munich and London: Prestel, 2017). May 20, 42.

[11] See Lauren Berlant and Lee Edelman, Sex, or the Unbearable (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014).

[12] See: Preciado (2013).

[13] For a discussion of queer respectability, see: Jason Orne, Boystown (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[14] Didier Eribon has addressed these questions of multiplicity and queer solidarity. See: Didier Eribon, Insult: And the Making of the Gay Self (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004).

[15] How queer is effective beyond a project of identity politics is one of the major themes in Leo Bersani’s work. See for example: Leo Bersani, Homos (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1995)

[16] The critique of politics of visibility was mostly articulated in a post-colonial context, for example with Édouard Glissant’s notion opacity: Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1997).

[17] Peter Rehberg, “Queer Autofiction as Body Protocol”. In: Texte zur Kunst 29, 115 (2019), 102-15.

[18] Just a few names that belong to Preciado’s canon: William S. Burroughs, Kathy Acker, and Guillaume Dustan.

[19] Paul B. Preciado, “My Body Doesn’t Exist”. In: Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds.), The Documenta 14 Reader (Munich 2017: Prestel), 117-34, 120.

[20] Preciado (2017), 120.

[21] The original concept suggested by d14 was “Learning from Athens;” the ethics of “Unlearning” emerged as a critique of a didactic program that structurally risks repeating forms of colonization. See also footnote 1.

[22] Paul B. Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2019).

[23] “Legally speaking, the trans person is represented as a sort of exile who, having left behind the gender that they were assigned at birth (like someone who abandons their country), now seeks to be recognized as a potential citizen of another gender (or nation-state). The charter of rights a trans person possess is, in legal and political terms, similar to that of the migrant and refugee. They are both apatride: they have stepped out of the lineage of the nation-state, but also of patriarchy. They all experience the temporary suspension of their political status.” (Preciado 2017, 124).

[24] “The old world is based on concepts of belonging, identity, and rootedness. Our world, ever new, will be one of radical subjectivities.” (Adam Szymczyk, “The Iterability and Otherness-Learning and Working from Athens”. In: Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds.), The Documenta 14 Reader (Munich 2017: Prestel), 17-56, 32.

[25] Tony Bennett, “The Exhibitionary Complex”. In: Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds.), The Documenta 14 Reader (Munich 2017: Prestel), 353-400.

[26] Bennett (2017), 355.

[27] Szymcyk (2017), 27.

[28] Szymczyk (2017), 39.