Narratives Reshuffled: Collected Stories From/About documenta 14

Elpida Rikou

The team behind documenta 14 (d14) used different curatorial devices, such as the Chorus, to encourage visitors to create their own lines of inquiry into what appeared to be a very complex, even chaotic, exhibition map linking two cities in two different European countries. The Learning from documenta (Lfd) research group, of which I am a member, developed ethnographic and artistic responses to the d14 artworks by analyzing their spatial arrangements, curatorial statements, relevant publications, talks, and presentations. At the same time, the many social actors present in the field defined by d14’s activities in Athens and Kassel produced different types of stories influencing and commenting on each other’s initiatives. The Lfd team remained a sensitive recipient, transcriber and co-creator of many of these narratives.

The three brief texts compiled below represent my own attempt as a member of Lfd to give a more coherent shape to themed collections of narratives’ fragments in correspondence to the three parts of the present FIELD Special Issue. In fact, the focus of the first section of this Issue on “Narratives” was partly inspired by a workshop at the Learning from documenta closing event, which was entitled, precisely,“Narratives reshuffled.” The first part of my text summarizes the activities of this workshop, which focused on the weaving and binding together of diverse narrative threads. The second text corresponds to the Special Issue’s section “Conjunctures” and concerns the social phenomenon of “Rumors and gossip,” which were exacerbated during the presence of d14 in Athens and had a considerable influence on our own research. The third text, entitled “Fairy Tales,” is a minor contribution to the Special Issue’s “Cartographies” and focuses on a significant detail of my visit to the exhibition in Kassel. Each text can be read independently and also as a variation—and a selection of snapshots—of the many stories from/about d14, which I happened to collect in my field diary.

Threads

In late September 2017, the Learning from documenta team replaced the d14 group at the premises where the latter previously held office—at the Athens School of Fine Arts at Polytechnic University building—in order to prepare for our closing event. We intended to underline the interaction of art and theory of our project by hosting a conference and an exhibition in the same space. However, our plans changed due to architecture. There was an auditorium on the ground floor, which was suitable for the conference and immediately accessible to all, but for the workshops and the display there was space available only in the basement. Thus, to find the art exhibition, a visitor would need to make an extra effort to follow a sinuous path outside the building and descend down some stairs to a large underground room leading to a corridor.

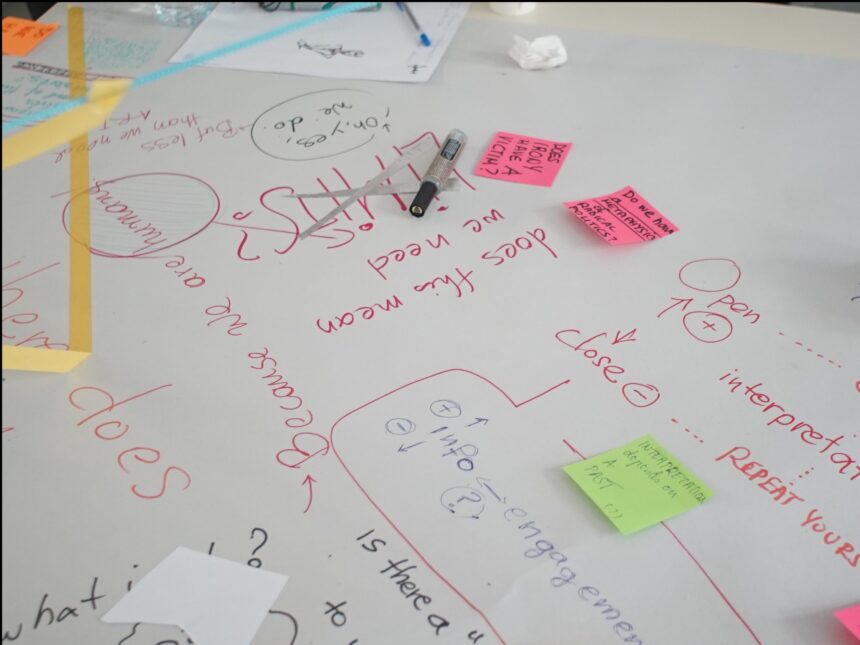

The aim of the Narratives reshuffled workshop [1] was to produce independent results as well as to collect the outcome of three ongoing workshops—Southern Teachers, Walking and Mapping, and Ruinous Pasts, Presents (and Futures?)—in order to channel the collective production into the exhibition in progress. For four days, we worked together as a group with d14 publications at hand. We transcribed questions and comments, sometimes on camera but mostly by writing on a paper roll that ran all along the table and continued onto the floor of the room, into the corridor where the exhibition was situated. To link the points we were textually recording we used strings attached to the walls. To make some important remarks more noticeable, we created collages of paper, posts and other materials. Soon, this participatory artwork took the form of a colorful, complex installation. To present the work, we proposed that the visitors choose a part of the installation they wished to know more about and anyone of us would respond by creating yet another layer of narration.

During the workshop, we pulled a loose thread of questioning here and there to observe how the seam of d14 narratives unraveled. One thread I was interested in pulling originated from the question “Why are you angry?” which was also the title of a film by Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer. [2] The ambiguous spectacle of Tahitian women on screen, similar to Gauguin’s depictions, left me wondering how exactly this was meant to challenge—rather than reproduce—“the gendered nature of art historical genius”. [3] I then searched for Nashashibi’s other works in d14 and the thread led me to Vivian Sutters canvases and to the collages of her mother, Elizabeth Wild, from which Nashashibi’s artworks were inspired. I noticed certain curatorial preferences. There were so many images of women and flora and some naked bodies, in gardens, wild vegetation, “primitive” settings, associated with earth, motherhood, simplicity and exhibited in spaces equally alluding to nature, such as the Natural History Museum in Kassel and the Philopappos Hill in Athens (among other venues). Were these persisting coagulations of images and references able to undermine the stereotypical association of femininity with nature, deeply rooted in European history? How was the deconstruction to happen when, on top of that, there were poetic texts coming from d14 curators (Paul Preciado in particular) indicating that “the skin and the womb, the oil and the coffee, the flesh and the gold, characterizes a generic “South” evidently linked to Greece? [4] Were these curatorial choices justified in terms of ecofeminism or/and strategic essentialism? In my opinion, they indicated the counter effect of the powerful binaries infiltrating the curatorial discourse of d14. A web of exoticizing essentializations—unchallenged as they were considered subversive—gradually entrapped the visitors throughout the whole exhibition, functioning as stereotype solidifiers.

d14 narrative lines also appeared to intersect with the participants’ personal trajectories in diverse ways. In a personal communication Gwen McGregor, for instance, a Toronto-based artist who used d14 as a case study for her Ph.D. in Cultural Geography, still remembers her answer when asked by another workshop participant to choose between North or South, without any further explanation. “North, I guess, because I live in Canada,” she replied but remained perplexed. She understood Canada as part of the “global North”, not just geographically but politically. However, while in Canada, she would identify with “South” because, like 80% of Canadians, she lives within 100 km of the American border, whereas “North” brought to her mind the multitude of indigenous peoples who live in the North, many of whom struggle to gain recognition and financial support. The workshop also offered the occasion for new artworks—and narratives—to develop as in the case of the video essay entitled arrkk/afterlives. The video was created by Tatiana Ilichenko, a Berlin-based, Russian visual artist and filmmaker, as a personal critique of d14 and the ethics of engagement with the “Other.”

Threads from these two artists’ quests as well as from the interests of all other participants in the workshops were gradually knitted together to form part of the narratives of the exhibition-in-progress. The exhibition, curated by Eva Giannakopoulou, Dimitra Kondylatou and myself, was defined by its spatial arrangement that extended the trajectory of the “stream” of the paper roll installation of our workshop, which also included photos and videos of the Learning from documenta team members and invited guests. Some of the themes tackled were heritage, memory and expectations, imaginary geographies, gender and nature, affect and the critique of stereotypes, art as spectacle and as politics, participation and observation, documentation and copyrights. The works were either created beforehand or in situ by the workshop participants. Most of them are described in length by other texts in this Issue, [5] but there are still some that need to be mentioned here to acknowledge the input of our collective thinking.

The Greek artist and ex-student of the Athens School of Fine Arts, Maria Nikiforaki, who has been living abroad for quite a while, transcribed on her iPhone her trajectory back to the city on the occasion of d14 and presented a video entitled Nostalgia and a Future Song About Athens. The Akoo-o collective documented their walk (done in reverse, i.e. walking backwards) commenting on the atmosphere of uncertainty in Athens and the expectations created by d14. Vassiliki Sifostratoudaki presented a collage of found and printed material recording her experience as a spectator and an employee of documenta in Athens and Kassel. A video by three young artists from Berlin—Selina Lampe, Valentin Hessler and Michael Reindel—was created precisely to comment on d14, claimed ironically I am artist too. Gwen McGregor’s photos of the lobbies of art spaces commented, more generally, on the spectators’ gaze. Iraklis Κopitas’ molds of bullet traces on Athens’ buildings marble surfaces commemorated controversial moments of Greek history (which was oversimplified by a certain d14 curators’ approach). The film Echo (2014) by the visual artist Fiamma Montezemolo, working in the intersection of art and anthropology, was set on the border between Mexico and the U.S. and presented ethnographic research on the afterlife of artworks created during a public art event. The film highlighted the procedures of intrusion as a dimension of anthropological, artistic and curatorial intervention and was in dialogue with the video talk On intrusion, (alluding also to d14’s representation as an “intruder” in Greece) created by the anthropologist Tarek Elhaik.

With the closing of the exhibition, we considered the experience fulfilling, although criticism was voiced from a few participating artists who felt underrepresented, due to the underground settings provided for art. It is true that fighting for visibility makes careers in the art world, and we have certainly learned that from documenta. But working from the basement has its own value, at least for those who, on their own terms, are willing to examine which artwork’s underground currents bring and to forge their own narratives of the contemporary.

Rumors and Gossip

Institutions have “big stories to tell which set the narrative agenda for the smaller, individual stories that follow along.” [6] But at the same time, small stories, such as rumors and gossip, expose taken-for-granted social structures and enable minuscule forms of resistance to power or eventually solidify institutions and careers. [7]

documenta’s arrival in Athens created rumors and gossip, which circulated for a long time—before, during and after the exhibition. People talked allusively about the initial dinner party meant to establish an informal network of documenta collaborators in Athens. Rumors about what was to happen were exacerbated for some time before the opening, due to the secrecy enveloping different aspects of assembling the exhibition. This lack of information was quite difficult to handle for many art professionals in Athens (i.e. gallerists who were anxious about the repercussions documenta’s presence would have on the artwork) and particularly problematic for a research project like ours for which we needed to plan ahead. In the meantime, the stories circulating amongst the art crowd living at the Athenian Airbnbs and hanging out in the cafés and bars gave us access to the connoisseurs’ implicit knowledge about the image-making of this mega enterprise, facilitated by secrecy.

There was something to learn from documenta during that first period: the powerful effect that its presence had on people in the arts (whereas it seemed to have no effect whatsoever on the larger public, at least in Athens). The “magic” of art’s institutional power deepened antagonism and created new hierarchies in the spur of the moment. It was somehow amusing to compare this to the Lord of the Rings saga! documenta in Athens seemed to present “the opportunity of a lifetime” to many Greek (and non-Greek) artists and curators. One of d14’s long-term benefits for the Greek art scene is considered to be the boost it gave to careers, the networking and the know-how some people acquired by being involved in such an important exhibition. [8] I still recall a curator (whose name I have regrettably forgotten), speaking about the contemporary Greek art scene at the international exhibition Outlook, organized as a parallel event to the Olympic Games 2004. When interviewed by a journalist for a TV show, he said he saw no hope at all for the peripheral Greek contemporary art scene to come center stage any time soon! In this light, I was not at all surprised when, during a private conversation, a Greek artist told me that although (s)he was initially against d14 coming to the city for political reasons, (s)he was excited to participate when the proposal was on the table because, thus, her/his name was to go down in the history of art. The craving for the precious documenta Ring was propagated further and even certain art events organized in the city to run parallel to d14 opening were announced in such a way as to confound visitors on whether the participants were part of documenta or were simply exhibiting while documenta was in Athens.

Rumors and gossip were amplified once documenta’s public program was inaugurated. The Athens Biennial was supposed to be in charge of it, but something didn’t go as planned. Learning from documenta had no access to information at that time, although we had asked for permission to do research within both institutions. It wasn’t until later on that we were able to learn the whole story of the conflicting encounter between the Biennial and d14 from reliable sources. This episode was of importance for our research because it provided evidence of documenta’s influence on the local art scene, but also, because it indirectly influenced our project, too, in the sense that we were caught quite off guard in the middle of personal and ideological conflicts between the interested parties. The result was the exacerbation of rumors of an attack, now supposedly perpetrated by us on the documenta team, following the round table The Politics of Curating that we organized. Actually, during this round table, which was open to the public, it seemed for a moment as if the “veil” of secrecy enveloping documenta 14’s activities was lifted and different parties took the opportunity to openly formulate their questions and criticisms vis-à-vis documenta’s curatorial policies in Athens. Although this might have offered, for all parties involved, the occasion of a valuable, spontaneous public debate on practices and ideas, it was interpreted by documenta representatives as pre-planned malevolent “public exposure,” and even more dramatically, as a kind of “People’s Court” (as we were told). Even our own former collaborators and friends in the arts and the academy (who were present and positively predisposed to or already collaborating with documenta) eventually turned against us. They accused us of not being proper hosts for our important documenta guests at this table, because we allowed criticism of their activity in Athens be “ungracefully” voiced. But, of course, gossip—which remains more powerful than any public confrontation—provided the due explanation that we were doing so because we were “jealous” of not having been invited to participate in the exhibition. Which, as the reader recalls, was never actually considered an option for our project at its inception. [9]

Nevertheless, we didn’t intend to present ourselves as documenta’s enemies (considering, also, that members of our group were fans and/or employees), but rumor had it that we were considered as such after the aforementioned round table. It seemed that our work was interpreted by some documenta contributors as more polemical than other artists participating in the exhibition, like a group formed to comment upon certain aspects of d14 from a queer perspective. [10] In fact, one day, a pair of documena members visited TWIXTlab [11] disguised as anthropologists from the colonial era. Astonishingly, the message was clear that this expression was in accord with certain d14 curators’ views on anthropology as a remnant of colonialism. From then on, it seemed best to some of us to maintain a distance between the two projects, although members of our team continued to participate in their group. Their profile was interesting in that it related to queer formations, the Athens Biennial and the Athens School of Fine Arts (which was also the documenta 14 “headquarters” in Athens). It was an example indicating the complex rearrangements of coalitions and conflicts in the art milieu, due to the presence of d14. These rearrangements also involved the academy at large, as several academics interested in art and politics participated in d14, and Greek political life more generally. The Syriza left-wing party in power during that period was rather favorable to d14’s presence in Athens, due to d14’s political agenda and to the cultural and economic benefits expected for the city. Important institutions’ power is pervasive, so the networks created were not limited in the Athenian art milieu. Thus, repercussions of the pro/con d14 situation that was created locally were felt in the aftermath of the exhibition, in the academy and the art world, as certain careers were boosted or impeded accordingly.

The issue of rumors— not supposed to be dispelled but rather embraced—was touched upon by d14’s program of education, the Chorus, and the Society of Friends of Ulises Carriόn. [12] However, the acknowledgment of this social phenomenon’s interest didn’t go as far as to trigger any exercise of self-reflexivity, along those of Freedom. Once documenta was gone, there was a book published in Greek, a crime novel entitled Den les kouvenda (You don’t say a word) by the writer Makis Malafekas (2018). The book successfully rendered the atmosphere of rumors and gossip, secrets and conflicts in the city, depicted as enchanted by the presence of d14. The novel’s title refers to a well-known song in Greek, with the following opening verse: “You don’t say a word, you keep hidden secrets and documents.” The singer is Sotiria Bellou, in honor of whom there was a “Society” organized by Paul B. Preciado during d14’s public program. [13] Malafekas’ plot seems partially inspired by rumors concerning documenta (which is supposed to be an anti-commercial exhibition but participating in it immediately raises the value of any artist’s production) and money (eventually, money laundering). This is the “secret” documented by a painting, in the novel, giving reason for murder. What a totally different atmosphere depicted than the one, more joyful and idealized, emanating from documenta 13’s (2012) address to Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas, who wrote the semi-fictional novel The Illogic of Kassel (2014).

Fairy Tales

Sometime after the opening of d14 in Athens, an event was organized in which two artists and professors from the Athens School of Fine Arts, Zafos Xagoraris and Panos Charalambous (then, also Rector of the School) participated alongside the curator Katerina Tselou, the Assistant to the Artistic Director and Curatorial Advisor of d14. They talked about documenta, in particular documenta 6 in the year 1977, which they characterized as “their point of departure.” [14] Being amongst the audience that day, while personally knowing these two artists and appreciating their work, I was particularly sensitive to the tone of admiration and nostalgia in their talk. I, then, understood their decision to initiate the close collaboration between d14 and the School of Fine Arts not only as a wise professional and institutional choice, but also as an act of tribute to the inspiration they got, at a personal level, from their visit to Kassel four decades ago and the aspirations it generated in the then-young artists coming from a country whose contemporary art scene remained uncharted internationally.

Arguably, documenta’s influence on the development of contemporary art resides not only in its institutional capacity to contribute to the building of careers, but also to the idealization of a specific kind of art production that it promotes. There is a psychic component to documenta’s social and political power that might have to do with the entrapment of the visitors and all its contributors by the seductive tale of a hub, in the heart of old Europe, where new radical art is susceptible to serve as the canon of art production worldwide.

For my part, it was only in 2017 that I travelled to Kassel for the first time, for the needs of our research project. [15] I did not particularly adhere to the myth of documenta but I was somewhat respectful because I still viewed art as a liberating power. I was ready to participate in art tourism in order to gain a personal experience of the city during the famous exhibition.

The difference in atmosphere between Kassel and Athens struck me immediately. The former seemed like a museum as a whole, so well-kept and orderly, with neoclassical elements referring, in a sense, to an idealized image of the latter, which was much more diversified and chaotic. Marta Minujín’s Parthenon of Books and the Antidoron of the EMST, right in the middle of Kassel, made the connection the artistic director wished to create between the two cities obvious. But I found the Neue Neue Gallerie at the brutalist Neue Hauptpost a scenography more in accord with the spirit of d14; the work Forensic Architecture exhibited was certainly amongst the most poignant. The former underground train station, KulturBahnhof, was supposed to be the visitor’s point of entry into the exhibition [16] but it so happened that it was my own exit point, connecting me again with Zafos Xagoraris’familiar work, The Welcoming Gate (2017). [17] It was inspired by the hybrid state of the prisoner/guests in Germany, a position which a number of Greek soldiers found themselves in during WWI that left me with the impression that the artist wished to comment, quite elegantly, on the situation that the Athens art scene faced upon the arrival of d14.

Just before leaving, however, the Grimmwelt, a somewhat less prominent venue of d14 finally seduced me by its reference to the Grimm brothers’ world. Should I consider as contradictory the fact that my research on the most prominent institution promoting new radical art—this almost invasive art massively exhibited in two cities—eventually guided me back to folklore, the verbal art of inherited wisdom of the so called “common people?” Of course, folklore has long been criticized by anthropologists as closely related to the process of nation-building in Europe during the nineteenth century. [18] Today, it is clearly differentiated from popular culture due to folklore’s localized, participatory and variable nature, which negotiates collective memory and social identity. It is even considered somewhat outmoded in comparison to the latter, which remains under the spotlight of cultural theory and art production. The term “folklore” itself, first used to signify the study of traditions in 1846 by the British editor William John Thoms, was inspired by the works of the brothers Grimm’s Volkpoesie. [19] What probably sparked my renewed interest was that, whereas documenta was inspiring “fairy tales” for contemporary artists, so to speak, folklore referred to a form of artistic communication of the everyday life of people producing culture without being specialists of a sort, therefore indicating art as a more spontaneous, generalized, social process and less an individual career achievement.

At Grimmwelt, the brothers’ oeuvre as lexicographers and linguists resonated successfully with the emphasis on language and literature given by the artists of d14 whose work, exhibited there, demonstrated their effort to overturn “the basic architectures of repressive, patriarchal, malevolent society.” [20] Given that the context influences the viewer, their stories appeared to me less as individual works of art to admire and more as documents of overlooked details of history of Germany and Europe before and after WWII.

In the basement of the museum, an adventure space was designed to “connect factual themes with emotions,” [21] addressing the spectators as knowledgeable children engaged in what the Grimms called “root research” on language, symbols and fairy tales. An intricate plot combining texts and images in the d14 artists’ different styles developed on the ground floor with Roee Rosen’s The Blind Merchant [22] and Tom Seligman-Freud’s children books’ illustrations [23], among others, making history resonate emotionally for the visitors as psychical reality of suffering and trauma. Thus, the violence and the comfort of the fairy tales were more deeply felt, more surely leading the spectator to a Mighty Forest, as Dieter Roelstraete put it: the forest of the collective mindset is eventually more obscured than comprehended as a context for art by the idealized political discourse of d14.

As Roelstraete writes, the obsession with fairy tales in the nineteenth century expressed a German inclination to seek resolutions of social conflicts within art.

This proclivity endures most definitely today as well, if we consider the mighty fortress of documenta to be part and parcel of this psychosocial history and think of the quinquennial mega-exhibition—from its founding in postwar, Cold War–era West Germany (and in deep Grimm brothers territory to boot), via its transformation in the globalizing 1990s, to its present-day anchorage in the unlikely coupling of Kassel and Athens—as one more expression of that unnerving German inclination ‘to seek resolutions of social conflicts within art.’[24] Why such resolutions are sought in the realm of art, and how exactly they are found there are questions that must remain unanswered for now—another time, another essay perhaps?—but suffice it to say that, as far as this resident of an erstwhile Grimm brothers haunt is concerned, one could think of a great many worse ways of ‘resolving’ social conflict in crisis-ridden contemporary society.[25]

Would one agree with Roelstraete that art is a good way for resolving social conflicts? Not that this political role attributed to art doesn’t seem promising, but in what way should this role be performed? After the experience of d14, I personally sensed the need for a choice to make. Why work anymore in favor of art institutions such as documenta, thus contributing (even indirectly, by engaging a research on them) to the promotion of a few artists or curators as stars and encourage art, which masks conflicts by constructing fables of subversive ideology for the consumption of art tourists? Why not give one’s energy and knowledge to enhance “common people’s” (one’s self included) direct implication into art making, empowering individual and collective efforts to reveal psychic and social conflicts via contemporary wild, dark, memorable fairy tales? Should this be considered a naive and outmoded endeavor?

While writing these lines, at the same time that the news broke of the coronavirus pandemic, I happened to come across the announcement of an exhibition opening. The exhibition was entitled, precisely, Folklore (Centre Pompidou, Metz, from March 21st to October 4th 2020): “Associated with tradition, and therefore in appearance opposed to the notion of avant-garde, the world of folklore, subject to multiple controversies, infiltrates in different ways large areas of modernity and of contemporary creation. Far from the clichés of being backward-looking and artificial, artists have been able to find in it a source of inspiration, a regenerative power; as well as an object of critical analysis or of contention.” [26] Could it be that the changes induced by the pandemic to the habitual functioning of the art world actually signal the moment of—yet another—quest for a regenerative power sought for in more collective, less antagonistic and monetized exchanges, via, but also beyond, what “art” is constructed to be nowadays?

Elpida Rikou has studied sociology, social psychology, anthropology, and visual arts in Athens and Paris. She has taught at several different universities since 1998. She has also taught Anthropology and Contemporary Art in the Athens School of Fine Arts from 2007 to the present day. She is the editor of Anthropology and Contemporary Art (Alexandria, 2013) and of the translation into Greek of Marc Augé’s Pour une anthropologie des mondes contemporains (Alexandria, 1999). She has co-edited two volumes combining works by artists and contributions from social scientists on value (Αξία / Value, Nissos, 2018) and on voice (Φωνές/Fones, Nissos,2016), as well as the translation into Greek of Alfred Gell’s book Art and Agency (M.I.E.T., forthcoming). She has published articles in scholarly journals, edited collections, art catalogues, and newspapers. She is the co-founder of TWIXTlab (2014 to the present day), a laboratory between (twixt) art, anthropology and the everyday, and the coordinator of several art projects with a transdisciplinary character in which she is also a participant as an anthropologist and visual artist.

______________________________________________________________

Notes

[1] Workshop participants: Maria Juliana Byck, Eva Giannakopoulou, Tatiana Ilichenko, Dimitra Kondylatou, Maria Nikiforaki (visual artists); Vassiliki Sifostratoudaki (visual artist, graphic designer); Gwen McGregor (visual artist, assistant professor OCADU Toronto, PhD Candidate Geography University of Toronto); Apostolos Lampropoulos (literary and cultural theorist, University Bordeaux Montaigne); Vanessa Divani, Anastasios Fakinos (students of theory and history of art, Athens School of Fine Arts); Christina Anagnostou, Grigoris Gkougkousis (students of social anthropology, Panteion University). Coordination: Elpida Rikou.

[2] “Nashashibi/Skaer Why Are you Angry? revisits Gauguin’s vision of the South Seas while scrutinizing the transformative power of the interplay of looking and being looked at…Nashashibi/Skaer’s films often begin with an interpretative take on the creations of other artists to then unfold into a sequence of cryptic associations and loose references that expand on and complicate the initial inquiry.” See: https://www.kw-berlin.de/thelastmuseum/start

[3] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/nashashibi-skaer-why-are-you-angry-t15054.

[4] Paul B. Preciado, “Let Your South Walk, Dance, Listen and Decide,” in d14 Public Paper Issue No. 2 (April 21- May 4, 2017). Preciado has published a text with three parts, each part written in a different language. The text cited here, about the South, was published in Greek only (“O Notos ine to derma ke I mitra.Ine ladi ke kafes. Ine sarka ke chrisos”). North was described in English as “the soul and the phallus, sperm and currency” and in German it was declared “Der Süden existiert nicht.” See: https://www.documenta14.de/en/news/25689/documenta-14-public-paper.

[5] See the texts of Natasa Biza, Grigoris Gkougkousis, Sofia Grigoriadou and Giorgos Samantas, Panos Sklavenitis, Fotini Gouseti and Eleana Yalouri, Vassiliki Sifostratoudaki, Eleana Yalouri in this issue.

[6] Jacqueline O’Toole, “Institutional Storytelling and Personal Narratives: Reflecting on the ‘Value’ of Narrative Inquiry,” Irish Educational Studies 37, no. 2 (2018): 175-189, https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2018.1465839.

[7] Patricia Ewick and Susan Silbey, “Narrating Social Structures: Stories of Resistance to Legal Authority,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 108, no. 6 (2003): 1328-72. Pamela J Stewart and Andrew Strathern, “Gossip – A Thing Humans Do”, Anthropology News, February 20, 2020, https://www.anthropology-news.org/index.php/2020/02/20/gossip-a-thing-humans-do/.

[8] See for instance the Greek curator’s Sozita Goudouna’s interview: “Sozita Goudouna on the Athenian Art Scene,” Interview by Maik Novtny in Falstaff das Design Magazin, https://www.falstaff.at/living/.

[9] The round table on the Politics of Curating and other important issues concerning our project’s relations to documenta 14 cannot be developed here. See the introduction to this Special Issue by Rikou and Yalouri.

[10] http://documena.weebly.com/about.html.

[11] TWIXTlab is a project between art, anthropology and the everyday, which is situated in the neighborhood of Pangrati, Athens. See: http://twixtlab.com/.

[12] See for instance the following links for educational information: https://www.documenta14.de/gr/public-education/. For the use of rumors in the work of the Chorus, see: https://www.documenta14.de/en/news/25689/documenta-14-public-. For the Society of Ulises Carrion, see: https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-programs/5155/the-society-of-friends-of-ulises-carrion.

[13] https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-programs/1034/the-open-form-societies.

[14] https://www.documenta14.de/en/calendar/20558/-5-documenta-6-from-a-jacob-s-ladder-to-a-tv-bed.

[15] We travelled to Kassel with Eleana Yalouri in June 2017, invited by Professor Kathrin Wildner to present our project to her students at HafenCity University Hamburg and visit the exhibition with them.

[16] https://www.documenta14.de/en/venues/21712/former-underground-train-station-kulturbahnhof-.

[17] https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13685/zafos-xagoraris.

[18] For a relatively recent and comprehensive study, see Timothy Baycroft and David Hopkin (eds), Folklore and Nationalism in Europe During the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 4 (Boston: Leiden, 2012).

[19] https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0131.xml.

[20] https://www.documenta14.de/en/venues/21719/grimmwelt-kassel-and-weinberg-terrassen.

[21] https://www.grimmwelt.de/en/news/adventure-space-grimm-world/.

[22] https://www.roeerosen.com/the-blind-merchant.

[23] https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/22765/tom-seidmann-freud.

[24] Roelstraete refers to Jack Zipes, The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002) p.121.

[25] Dieter Roelstraete, “A Mighty Forest,” South Magazine, Issue 8, https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/899_a_mighty_forest.