Inside Beuys, Andres Veiel’s New Documentary on the German Artist

Cara M. Jordan

Directed by Andres Veiel. Wide release in Germany in summer 2017. Showing across the US February–May 2018. See kinolorber.com for show times.

In German with English subtitles.

Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) is one of the best-known artists of the twentieth century—particularly within his native Germany. Nearly every German person, regardless of their profession or class, has heard about the man, his artwork, and his politics. Most modern art museums in Germany contain at least one of his drawings, multiples, or vitrines. Although Beuys is known in the United States, he is far from being a household name here. His work has long been celebrated by US artists, but critics and art historians have struggled to agree on his central role in the trajectory of European art. As a result, there has been a misunderstanding of Beuys’s work as “too German” or “esoteric” and of his persona as “cult like.” While his multiples circulate regularly in exhibitions, the last major retrospective of Beuys’s work was in 1979–80 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Only recently has he been recognized more internationally as a pioneer in the field of socially engaged art, primarily for his theory of “social sculpture”—the idea that all people have the creative capacity to shape society—and his promotion of interdisciplinary creative education.

Beuys, an inspiring new documentary film directed by German artist and filmmaker Andres Veiel, premiered at the Berlinale film festival in 2017 and is now making a tour of US cities including Chicago, Houston, New York, and Los Angeles. It brings the artist’s work to life for a much broader public for the first time, thereby expanding the familiarity of Beuys’s oeuvre outside of Germany and specialist circles in the United States. Successfully splicing together rarely seen archival photographs and film footage with contemporary interviews of Beuys’s colleagues and confidants, Veiel makes a valuable contribution to the current literature on the artist by exposing Beuys’s personality and some of the more ephemeral aspects of his practice. Unlike many art historians and critics who have previously written about Beuys, the filmmaker manages not to pigeon-hole him in any one discourse. Beuys also reveals some of the inherent contradictions in the artist’s personality that still consternate viewers of his work today. However, the film only alludes to his political engagement and activist tendencies in his art. Therefore, while its visual panoply delights both neophytes and connoisseurs of Beuys’s work alike, it only does so as a primer for those who wish to expand their knowledge of the artist beyond his iconic sculptures and performances.

Most viewers of this film will probably already know of Beuys’s monumental margarine and felt installations, as well as of his performances involving animal bodies, which gained him worldwide renown beginning in the 1960s. These works are usually experienced today either firsthand in museum galleries or through film stills and photographs, many taken by Beuys’s ever-present documentarian, Ute Klophaus. Veiel’s documentary does not disappoint viewers who are interested in this facet of his practice. The film lingers for poetic moments on photographs of gallery-sized installations like Plight (1985), a felt-lined room with a piano, and Show Your Wound (1974–75), an amalgam of twinned objects including hospital gurneys and blackboards. It also contains ample archival film excerpts of performances such as How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), in which the gold-leaf covered artist whispered incoherently to an animal corpse, and I Like America, and America Likes Me (1974), during which the felt-shrouded artist interacted with a live coyote for three days in the René Block Gallery in New York.

Although these works are now iconic, Veiel’s film is unique in that he animates them through a variety of media. Celluloid film and black-and-white photographs of artworks transform into moving images of their installation by the artist. Audio of Beuys’s voice overlaid on still images shifts into film footage of Beuys in conversation with an off-camera interviewer. More so than many artists of his generation, Beuys’s life and work were documented in many different forms—often at the same time—and Veiel has done a marvelous job of uniting them into a more complete picture of the artist than the one that currently exists in exhibition catalogues and monographs.

Written descriptions of these works often categorize Beuys interchangeably as either a Fluxus, conceptual, or performance artist—none of which come close to describing the artist’s interests nor his cohort, though all apply to some facet of his work. Fluxus, the most-used moniker, for example, was used by the artist himself into the mid-1960s, although his participation in Fluxus activities lasted only a few years and his work diverted from their original intentions in many ways. The lack of a clear link between his work and art historical precursors such as Duchamp has come as a great source of frustration for critics, in particular, who often have a difficult time describing, much the less framing Beuys’s work. As a result, his work has often been labeled as singularly German. Those looking for insight in this film will quickly realize that Beuys’s complexity naturally results in a multitude of possible interpretations.

During his lifetime, Beuys insisted on explaining his own work himself. He often guided the placement of works and physically remained in the gallery for days and weeks on end to discuss the work with visitors in person. A generous interlocutor, Beuys’s dialogues often included in-depth explanation of his philosophy on art, which was heavily based on the writings of Novalis and Friedrich Schiller, and the Anthroposophic teachings of Rudolf Steiner. Beuys often referenced Steiner, in particular, whose own post–World War I lectures dealt with the need to heal society through the development of creativity. The artist spent endless hours challenging his audiences about art’s role in changing society, developing his rhetorical skills over time between the 1960s and ’70s. This in itself is a testament to his appeal to today’s socially engaged artists. It is important to see this activity as a clear precursor to the sorts of audience interactions instigated by artists such as Liam Gillick and Rirkrit Tiravanija that occurred within museums primarily in Western Europe during the 1990s, now known as relational aesthetics, as well as the more interactive exchanges with a philanthropic intent that occur outside of museum and gallery walls in the US and worldwide initiated by today’s social practice artists including Tania Bruguera and Rick Lowe.

Nowadays, viewers can merely witness Beuys’s form of audience engagement through film documentation, rather than experience it firsthand. However, Beuys is unique in revealing the artist’s development and process, thereby contextualizing his works’ current gallery configurations and taking us one step closer to the artist himself and to his art. Veiel has made generous use of seldom-viewed archival materials, including those from the Joseph Beuys Media Archive, which has been closed to researchers for several years (it has recently moved to the Zentrum fur Kunst und Medien in Karlsruhe, Germany). The filmmaker’s editorial and research team scoured some 300 hours of film footage and received permissions from innumerable photographic archives. With the help of this rich source material, Beuys provides a much-needed overview of the artist’s life and work that expands on the extant literature on the artist through the film’s sheer visual prodigiousness.

The film slowly tracks Beuys’s initiation into the field of art, beginning with a furtive period of drawing in the 1940s and ’50s to his establishment as a star in the 1970s and ’80s. As a scholar of Beuys’s work, I was pleased to see the numerous behind-the-scenes images of his more famous installations. For instance, we learn that The Pack (1969), a Volkswagen van overflowing with small sleds packed with felt, margarine, and flashlights now permanently installed in the Neue Galerie in Kassel, Germany, was once staged by the artist outdoors in the middle of the countryside (fig. 2). By integrating the story of the artist’s development with images of these pieces, Veiel works against prevailing readings of Beuys’s sculptures that isolate them from the rest of his oeuvre. These include his participatory public projects, such as the Organization for Direct Democracy, established in 1970 to educate the public about how they could directly engage in government processes, and the Free International University (FIU), an interdisciplinary educational initiative he founded with a group of collaborators in 1973.

While such exclusive glimpses are worthwhile for all audiences, the organization of the film is neither chronologic nor thematic. Rather, it is guided by the works themselves. This makes it less than ideal as an introduction for those without a thorough grasp of German postwar history or the events in Beuys’s life. From a discussion of Documenta and the importance of his environmental project 7,000 Oaks (1981–87), the film jumps back in time to the artist’s youth in Kleve, a small town in northwest Germany, and then to his time in the Nazi Luftwaffe, and forward again to his heyday in the 1970s. Unfortunately, several scenes are not narrated or labeled, such as his appearance at the Düsseldorf Academy (he both trained there in 1947–1953 and taught there, primarily in 1961–72), which may make it difficult for uninitiated viewers to trace the sequence of factual occurrences of Beuys’s life. Veiel seems to have taken for granted that while German audiences are already quite familiar with Beuys’s résumé, international viewers will need further contextualization.

The tale of his salvation from a plane crash by a nomadic group of Tartars—perhaps the best-known story about the artist—is narrated by two interwoven narratives: Beuys’s fantastical account of the events and an interview with the artist in which he skirts questions about its veracity. In my opinion, Veiel’s subtle method of poking holes in this story does not go far enough in revealing that this was a fiction created by the artist in the 1970s, when his celebrity was rising, rather than an actual biographical event. As Peter Nisbet has described in his essay in Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy (2001), this singular piece of information, debunked decades ago through archival evidence, has been repeated so often that it is assumed to be the truth. Further, Beuys’s connection to the Nazis, which cannot be denied, has been the source of much of his demonization within the art world. However, Veiel’s unwillingness to explicitly address the new research on this period in Beuys’s life only promotes an essentialist reading. Critics’ focus on this salacious aspect of Beuys’s biography has undoubtedly overshadowed what is now generally considered to be the artist’s intent: that the materials in his work serve as symbols for the healing of society at large, the very same principle that he imbued in his participatory public projects.

Beuys’s focus is on the artist’s humanity, rather than his greater-than-life mythology, a strategy that is rarely taken in accounts of his life or work. Veiel spends considerable time examining Beuys’s life just after he returned from the war, when he went through a period of deep depression and malnutrition that contributed to his later physical well-being and mental concentration on art. This includes testimony from a number of interview subjects, notably an early collector, Franz Joseph van der Grinten, and Beuys’s longtime companion, curator and critic Caroline Tisdall. From these interviewees, we learn that Beuys had numerous health issues and that he spent long periods of time in the hospital as a result of his superhuman work ethic. According to the film, he only slept a few hours per night in order to increase his productivity. Such insights into Beuys’s everyday life—never discussed in literature on the artist—allow viewers to connect with him as a real person, as opposed to the archetypal image of the artist as a distanced, shamanistic figure. His story proves that even artists who we think of as successful have experienced hardship, struggle, and even failure. However, it also exposes some of the inherent contradictions in Beuys’s art and life. For example, at the same time he preached against capitalist excess, he drove around in a luxury automobile. While his work was devoted to interpersonal exchange and direct democracy, his hyper-intellectualized explanations of his own work could be inaccessible to laypeople. Problematic as this may appear for today’s viewers, Beuys was a known provocateur who reveled in the discussions brought on by these inconsistencies.

Beuys’s reputation for marathon lectures and the ritualistic tone of his performances has often prompted critics in the United States to characterize him as a pedagogue and cult-like leader (as in, for example, Benjamin Buchloh’s legendary 1980 Artforum critique, “Twilight of the Idol”). This interpretation, which emerged at the same time as the anti-cult movement was gaining support in the US, has had a particularly detrimental impact on his reception in the United States. In my view, it is a major reason why his work is less discussed and circulated here than it is in Europe. Although Beuys had a reputation for manipulating the media with his incessant proselytizing of his own artistic vision in a manner some critics likened to fascism, his methods were not unlike many other socially conscious artists worldwide who have sought to broaden the audience for their collaborative projects to national and international audiences since the 1970s. Beuys was particularly excited by the radical potential of feminist artists in the United States, for example, who used equally spectacular methods to attract popular attention to their cause and their artwork (the film shows a clip of his meeting with a group of feminist artists and writers in New York). If nothing else, he always had a clear, consistent message about art’s role in social life. He was also instantly recognizable in his felt hat, fishing vest, and jeans—the ultimate figurehead for the revolutionary movement he hoped to initiate through art. This set a powerful precedent for artists in the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, including Mel Chin, Mark Dion, Michael Rakowitz, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who were searching for their own methods to merge their activist concerns with their art practice, while finding a public-facing image for their dematerialized projects.

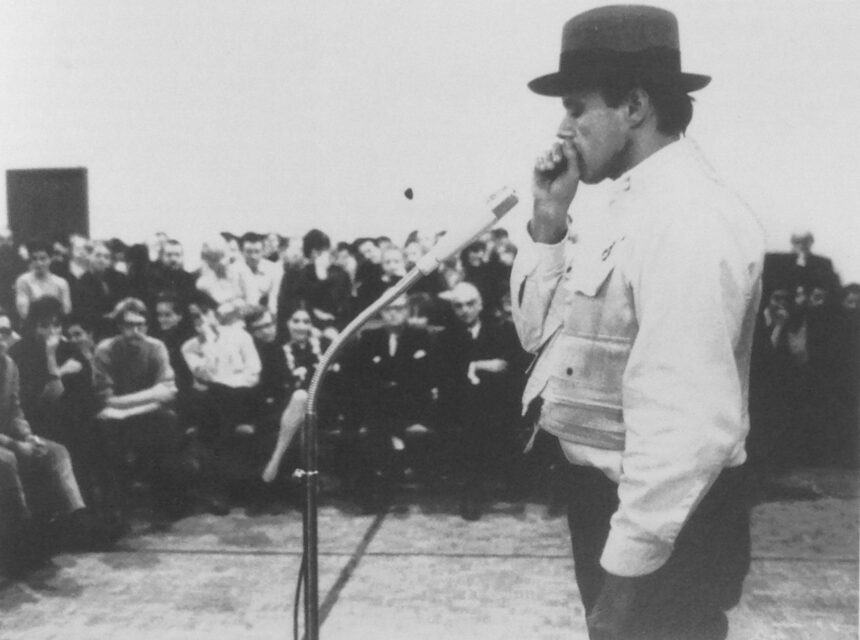

Beuys has never ceased to cause controversy within Germany, although not for entirely the same reasons as in the United States. On the one hand, he ran into problems in Germany for his association with former Nazi party members and sympathizers, such as his collector Karl Ströher and his collaborator Karl Fastabend. On the other, he was known as a rambunctious character, full of life and energy, who was constantly surrounded by an adoring group of followers. These aspects, lesser known to non-German speaking audiences, appear throughout the film, and demonstrate that he was not as un-relatable as his many somber portraits might lead us to believe. He was an extremely charismatic figure, who was known for his broad smile and good sense of humor––indeed, documentation of his performances still conveys this comicality. For example, during a ceremony marking the opening of the fall semester at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in 1967, the artist took the microphone and launched into a series of animalistic grunts for a performance he called öö-Programm (fig. 2). During the screenings of Beuys that I attended in Germany in 2017 and New York in 2018, audiences still erupted in laughter at the ridiculousness of this action.

What lies beneath the surface, not addressed in the film, is the historical context that made Beuys’s work revolutionary not only in art, but also in politics. This is an important aspect for those interested in his politicized concept of aesthetics. For although the artist had a significant role in the founding of the German Green Party, his political involvement began in the early 1960s when he was teaching at the Düsseldorf Academy. There, he developed the idea that society, and thereby politics and economics, could be reorganized under the aegis of art. The performance described above was rich with political connotations, as it came just months following the escalation of student protests in West Germany. Ignited by the death of a protester in West Berlin in June 1967, the youth movement revealed the clashes between young people and the older generations who had lived through the Nazi years. Beuys’s action points to the absurdity not only of his own authority as a professor, but also to that of the school’s administration, which he would take head-on in the years that followed.

From this point forward, Beuys began to think of his actions in political terms, beginning with his organization of the German Student Party with his student Johannes Stüttgen and artist Bazon Brock the same year. During the next decade, he allied with a group of collaborators to create “social sculptures.” In 1970 he and Stüttgen established the Organization for Direct Democracy, a storefront space used to educate the public about ways to suggest their own referenda to address issues like nuclear disarmament, fair wages for women, and immigration through working groups and how to avoid engaging with the dominant political party system by not voting in elections. Following his public expulsion from the Düsseldorf Academy in 1972 for challenging state intervention in the art academy system and allowing un-enrolled students into his courses, Beuys also helped establish the FIU, an interdisciplinary learning environment that tackled similar issues through guest lectures, exhibitions, and a network of international satellite schools. Perhaps his most globally pervasive public artwork, 7,000 Oaks, drew on the idea of collaborative exchange as a means to address political issues like environmental destruction. The work involved the general public in the conception and installation of thousands of trees and accompanying basalt stones in Kassel, Germany. It was later repeated in cities worldwide, including New York, Leeds, and Sydney.

This political context is what makes Beuys so interesting for contemporary viewers who are interested in art as a form of activism. The film does provide valuable insight into Beuys’s politicization and highlights his more iconic works of social sculpture, but it heavily emphasizes the artist’s own defense of his work rather than his praxis. This has contributed to another misunderstanding of his ideas: that they were entirely utopian and obscure, and not at all rooted in reality. In fact, Beuys was able to navigate both modes of being simultaneously as a mystical figure who was committed to a legitimate political cause. While his artistic mindset certainly led to conflict with political activists, he was nonetheless highly influential to numerous young artists in West Germany—including the filmmaker Veiel himself—who were struggling to find a middle ground between the violent tactics of the extreme left Rote Armee Faktion (RAF) and the conservative politics of the Bundestag. In this regard, Beuys’s three major Documenta projects, the Organization for Direct Democracy (d5, 1972), Honey Pump in the Workplace (d6, 1977, part of the FIU), and 7,000 Oaks (d7), demand more than just a cursory glance. Social practice artists and theorists alike would benefit from a more nuanced discussion of Beuys’s methods of collaboration, the use of the media in his actions, and, above all, from an exploration of the political implications of his theory of social sculpture.

The film is narrated by Beuys, whose politically charged assertions are peppered throughout. For instance, he offers the following response to Picasso’s declaration that art should be a weapon to be used against the enemy: “the question is—who is the enemy?” Such pronouncements have provocative potential given the current political climate in Europe and the United States and the increasing popularity of the idea that art should be used to address pertinent issues. However, their impact could have been magnified had Veiel also included an explanation of who Beuys considered to be the enemy—the corrupt political party system and traditional state-run art institutions—and what the artist did to combat their effect on West German society. In relying heavily on the artist’s own words rather than analyzing them, Veiel falls into the trap that is endemic to much of the literature on the Beuys. Although his context was quite different from today’s, Beuys’s methods undoubtedly have much to offer those artists and academics who work to combat the corporatization of higher education and the decreasing ability of citizens to influence government.

As charismatic as he may have been during his own lifetime, Beuys’s political potency has not remained a part of contemporary debates about the efficacy of holistic education, the necessity of protecting the environment, or even the nature of democracy in the neoliberal state. There has been a recent increased interest in Beuys, evidenced by his inclusion in course syllabi about the history of socially engaged art, such as Pedro Lasch’s course, Art of the MOOC (sponsored by Duke University and Creative Time), and publications like Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (2012). Augmented in part by this film, this attention will no doubt lead to a deeper understanding of in these aspects of his practice in the years to come. In response to his critics, Beuys said that art had to be sensational to be interesting. The artist certainly embodied this as both a provocateur and a living contradiction. While Beuys certainly animates the artist’s work for contemporary viewers through a trove of archival materials, audiences are left alone to evaluate which of his ideals are most applicable to our present time. This struggle to establish the relevance of Beuys’s voice only furthers the artist’s continued lack of solid footing in any twentieth-century artistic movement. Nonetheless, Veiel’s film is a valuable addition to our knowledge base on this important artist.

I would like to thank Dr. Frank Hentschker, Dr. Petra Richter, Prof. Keith Wilson, and the Editorial Collective at FIELD for their helpful comments and reviews of this essay.

Cara M. Jordan is an art historian, educator, and editor. In 2017, she received her PhD in art history from the City University of New York Graduate Center, where she wrote about Joseph Beuys’s conceptual legacy in social practice in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s. Her research on Beuys and public art has been published in Public Art Dialogue, Seismopolite, the Journal of Curatorial Studies, and the exhibition catalogue of Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect. She currently serves as author of Peter Halley’s catalogue raisonné (JRP|Ringier, 2018) and is Provost’s Fellow for the Arts in the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center.

References

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London; New York: Verso Books, 2012.

Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. “Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol, Preliminary Notes for a Critique.” Artforum 18, no. 5 (January 1980): 35–43.

Nisbet, Peter. “Crash Course.” In Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy, 5–17. New York: DAP, 2001.