A Note on Socially Engaged Art Criticism

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen

If you were to take an overview of the most important critical artistic practices from the mid-1990s onwards and the attempts by art theory to analyse them, forgetting both the most applause-hungry provo artists such as Damian Hirst—whose critique of the art institution is almost non-existent—and spectacular, willingly instrumental creative city artists such as Olafur Eliasson, I think we would have to distinguish four overlapping practices: relational aesthetics, institutional critique, socially engaged art, and tactical media. It is evident, of course, that we are trying to account for phenomena whose identities are in no way fixed but are in movement, and that, for instance, former oppositions between the avant-garde’s anti-institutional “over-politicization” and anti-aesthetic institutional critique are gradually changing. Relational aesthetics would have to be the starting point for such an account of politicized contemporary art from the mid-1990s onwards. Nicolas Bourriaud’s plaidoyer for an “art of social interstices” that is open in its formal composition and invites the spectator to participate in some way was trendsetting on both sides of the Atlantic and still appears—even after the October-led bashing—as the most important way out of the 1980s critique of representation (and out of the reappearance of expressive or meta-expressive painting).[1] In his description of such artists as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pierre Huyghe, Jens Haaning, and also the late Félix Gonzáles-Torres, Bourriaud developed a persuasive vocabulary that referred to the avant-garde’s transgressive experiments but also distanced itself from them, and picked up insights from postmodern philosophy and its analysis of the disappearance of “grand narratives.” The new art Bourriaud wrote about and curated was characterized by working on and producing “inter-human relations,” he argued. Relational aesthetics was not a new artistic style or a particular theme but, instead, a particular way of using the art space with a view toward creating social relations. Through the use of aesthetic objects, the artist creates temporary social relations, Bourriaud explained, arguing that the new art was a response to a historical development characterized by the appearance of new forms of alienation and control. Relational art continued the avant-garde in a diminished form by creating small-scale, open utopias, by setting up alternative temporary free zones in which it was possible to interact differently. That was the argument, at least. Claire Bishop and others criticized Bourriaud for his seriously flawed understanding of the idea of the openartwork, arguing that it is, in fact, not the work itself but its reception that is open, questioning Bourriaud’s fairly loose use of terms such as participation, relations, and interstices in his analysis of works such as Tiravanija’s various food projects (Thai soup or sausages served at openings).[2] The inflation of words such as “creativity” and “participation,” which played a role in the expanded and bloated so-called experience economy that was part of the last phase of the neoliberal economy of speculation in which fictive capital kept a hollowed-out economy floating, casts a critical perspective back on Bourriaud’s theory. However, we should bear in mind that the theory of relational aesthetics was formulated in the early 1990s: before Richard Florida and his cohort wrote about the creative class, before every art institution “ordered” participatory artworks, and in a period when the Internet still somehow had an emancipatory aura.

If relational aesthetics and participatory art are the obvious place to start a genealogy of politicized contemporary art since the mid-1990s, socially engaged art comes next. Although this practice has clear roots in the 1960s, as has been described by, among others, Lucy Lippard, who used the term “Trojan horse” about interventionist art from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, a shift clearly occurred in the 1990s, in which socially engaged art acquired a new and different visibility.[3] If Bourriaud’s nomenclature was very successful, it is a bit muddier in this case. Socially engaged art has inspired a fair number of names—from Beuys-inspired “social sculpture” to more activist “interventionist art” to “community-based art” or “collaborative art.” However, “socially engaged art” seems to be the most common description for art that leaves the art institution and performs different kinds of interventions or artistic social work, often intended to create some kind of dialogue in conflict-ridden urban space.

Of course, terms such as socially engaged art and relational aesthetics are a mixture of art criticism, institutional attachment, and artistic practice—on the part of the practitioners themselves—and the terms tend to merge when, for instance, the characteristics of relational aesthetics become the characteristics of socially engaged art. The emphasis on dialogue is a common denominator from relational aesthetics to the different kinds of socially engaged art. Yet, whereas the relational art analyzed and promoted by Bourriaud has tended to remain securely embedded in the sacred space of the institution of art—museums, galleries and kunsthalles—socially engaged art has attempted to a much larger extent to take the relative autonomy of art outside the physical space of art by attempting to use the “freedom” of art to thematize or work on social issues or problems outside. Good examples of such practices include the refurbishing of the hostel Mændenes Hjem in Copenhagen by Danish artist Kenneth Balfelt from 2002 to 2009, Wochenklausur’s setting up of a drop-in center equipped with a bocce court for the elderly in a village north of Rome in 1994, or Suzanne Lacy’s “The Roof is on Fire” in which 220 young African-Americans staged a performance addressing police violence and racial stereotypes in downtown Oakland, also in 1994.

If relational aesthetics and socially engaged art are the two most important practices within politicized contemporary art, we also have to mention institutional critique and tactical media. Institutional critique was, of course, a continuation of a previous generation of conceptual art, a continuation of conceptual art’s “internal” exposition and critique of the conventions and rules of the art institution on the basis of the idea that it is not possible to find a position outside the institution. Post-conceptual artists such as Andrea Fraser, Christian Phillip Müller, and Fareed Armaly took on the role of self-critical sociologist, subscribing neither to a modernist idea of an autonomous artwork nor to the avant-garde’s anti-aesthetic exit from the institution highlighting the art institution’s structural constraints. If the avant-garde was transgressive and subscribed to an idea of the realisation and Aufhebung of art, institutional critique opts for an immanent approach and engages in a kind of “complicit critique,” continuing conceptual art’s self-critical investigation of the inevitable recuperation and commodification of art. These investigations are undertaken without the pathos-ridden rhetoric of the avant-garde and without any hope of transcending the institution, without an idea of a revolutionary break. If institutional critique is, thus, “realistic” and tries to use the autonomy of art instead of attacking it and doing away with it—there’s no outside, we cannot exit the institution but we can expose its workings—tactical media is characterized by a playful do-it-yourself approach in which artists use new media in a kind of semiotic guerrilla war against multinational companies and nation-states. Instead of focusing on the institution, tactical media intervenes in the remains of various national bourgeois public spheres. Brian Holmes described it as an expansion of art towards a transversal critical cultural practice or creative dissensus aimed at discussions outside the art institution but undertaken without the avant-garde’s historical-philosophical notion of a coming revolution.[6] Art and new media converged in an event, Holmes writes. There was a distinct Deleuzian and Negrist dimension in much of tactical media with its focus on lines of flight, networks, and movement. Tactical media were related to the alter-globalization movement and its summit protests in which artists not only “decorated” already existing political demands but played an important role in organizing a new creative protest movement that understood that anti-capitalist resistance does not only take place in the streets but also in mediated forms on screens. If relational aesthetics and institutional critique in different ways remained attached to or stayed within the art institution and, respectively, saw the art space as a place with a distinctive togetherness or as a compromised but inescapable sphere, socially engaged art and tactical media were more “centrifugal” and tried to activate the relative freedom of the artists outside.

If all these practices and the corresponding art theories emerged in the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, the question is what remains of these practices today. In retrospect, it is interesting to observe how relational aesthetics seems to have reached its zenith a while ago as a result of a massive institutional co-option. Bourriaud’s emphasis on art’s ability to produce interstices and sociality relatively quickly became part of a hugely expanding culture industry connected to a global circuit of cultural tourism and city branding. It became increasingly difficult to distinguish the micro-utopias of relational aesthetics from the artist-as-entrepreneur discourse of neoliberalism. Relational art’s openness became arty party and creative city discourse. Institutional critique suffered a similar fate, as it quickly became a fixed ingredient on the smorgasbord of contemporary art, where any institution worthy of its name commissioned artists to engage in critical interventions into the institution. At the same time, institutional critique fused curatorially and institutionally with relational aesthetics in new institutionalism, in which curators and directors of museums and art spaces started curating institutional critique, showing political representations or representations of the political inside the institution. The relative autonomy of art was thereby tested once more but primarily affirmed. In retrospect, the result seems to be recuperation across the board.

For a long period, tactical media seemed to have suffered the same fate as relational aesthetics and institutional critique. For different reasons, however. As Gregory Sholette and Gene Ray write in the introduction to a theme issue of Third Text titled “Whither Tactical Media?,” 9/11 and the war on terror seemed to have pulled the carpet from under tactical media.[7] The narrowing of the political horizon to a false choice between Western democracy and Muslim terrorism tended to remove the conditions for any kind of anti-capitalist critique. The emergency laws that were passed after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon criminalized both confrontational as well as more playful and creative acts of resistance, and both the alter-globalization movement and tactical media seemed unable to cope with the new anti-rebellion regime. The positive Stimmung of the Clinton years was replaced by a much darker tonality in which torture, surveillance, and politics of fear made the ironic and playful gestures of tactical media seem irrelevant. But with the sudden appearance of the so-called movement of the squares in 2011 inspired by the Arab revolts, tactical media was relaunched. With M-15, the Syntagma Square movement, Occupy and, later, Nuit Debout, tactical media has been revived as a political post-artistic gesture in which artists again take on the role of producer or organizer as Walter Benjamin famously wrote about the Russian avant-garde.[8]

And, then, there is socially engaged art. Compared to relational aesthetics and institutional critique, it has done reasonably well. Of course, socially engaged art has also been exposed to the same kind of recuperation and institutional co-option that pulled the carpet from under relational aesthetics and institutional critique—the caravan that played a central role in Balfelt’s refurbishing of Mændenes Hjem is, for instance, now securely installed at the National Gallery in Copenhagen—but not to the same extent as the two other practices that, to a much larger extent than socially engaged art, became part of the booming contemporary art economy in the 2000s, when financial capital suddenly took an interest in art.

That socially engaged art and the discourse of socially engaged art are still very much alive is evident from the journal FIELD: A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism, founded by Grant Kester. Kester is the driving force behind the journal, but it gathers a larger milieu of art historians, critics, and artists primarily based in the U.S. The editorial board is composed of art historians such as Shannon Jackson from Berkeley, the curator Nato Thompson from Creative Times, anthropologists such as George Marcus from UC Irvine, and artists such as Tania Bruguera—all household names within the field of politicized contemporary art. So far, four issues of the journal have been published online, featuring contributions by artist and writer Gregory Sholette, the squat researcher Alan W. Moore, and Polish-American artist Krzystof Wodiczko, among others. Sholette contributed to the first issue with a long text in which he revisits the seminal exhibition “The Interventionists”, which he co-curated with Nato Thompson in 2004 at MassMOCA, using it as a starting point to assess the development of socially engaged art since that time. Together with Gloria Durán, Alan W. Moore has written a text on a self-organized social center in Madrid, La Tabacalera. Wodiczko’s contribution is a text entitled “The Inner Public,” in which he takes the dominant reception of his public interventions to task for failing to deal with the collaborative character of his projects, focusing only on the visual détournement of urban space. The journal also includes interviews and reviews—fairly conventional journal genres; thus, what sets the journal apart from other journals dealing with politicized contemporary art is primarily the more anthropological case studies such as Moore and Durán’s. But we are far away from colorful contemporary art journals such as Artforum, Frieze or Flash Art: there is no advertising or short reviews of exhibitions; instead, FIELD offers in-depth accounts like Durán and Moore’s, in which projects are not only described and embedded into an art-historical context, but also contextualized politically with an emphasis on participation and the local milieu.

FIELD inscribes itself in a network of academic journals such as Third Text, which was started by Raseed Araeen in 1987 (and, shamefully, hijacked by the Board of Trustees in 2012), Miwon Kwon and Helen Molesworth’s Documents, which existed from 1994 to 2004, and Grey Room, published by MIT Press since 2000. But the great ghost, of course, remains October, which remains the dominant Anglophone academic journal on contemporary art.

If the often overlooked but important Documents seems in retrospect like a third generation October (Rosalind Krauss leading the first generation, the “disappeared” Douglas Crimp the second, and Krauss’ pupil Helen Molesworth the third), its attempt both to continue and exit from its inheritance (as a concrete journal but, more importantly, as art-historical practice, as matrix of interpretation and historical horizon) of being affirmative to the new institutional critique of the 1990s (Andrea Fraser, Mark Dion etc.), Grey Room could be described as a fourth generation October in which art historians attempt to establish a more trans-disciplinary journal in which visual art is just one subject among others including design, architecture, new media, and politics. FIELD is a different endeavour because it is not so closely related to October, but it is nonetheless forced to intervene on terrain that October dominates.

But FIELD rejects October’s art-historical vocabulary (what we might term the expanded field’s combination of a post-Greenbergian formalism and French structuralism) and turns to anthropology and sociology to account for the new socially engaged art that does not fit neatly within October’s framework.[9]

Kester defines the project as the production of “a new trans-disciplinary critique” that can perform the same kind of movement out of the institution in which socially engaged art itself engages. It is important to move beyond the aesthetic criteria of October, which remains attached to a focus on the artwork (and its formal composition).[10]

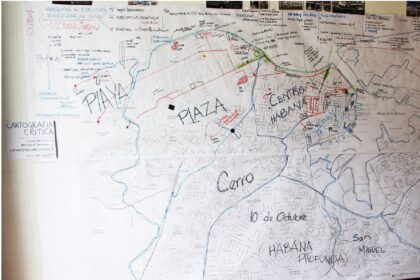

The new socially engaged art criticism should engage in “field analyses”—thus, of course, the name of the journal—Kester writes. The art historian needs to take seriously the social engagement of art and its way of engaging and collaborating with an extra-artistic audience and, thus, develop a kind of art ethnography in which the individual artwork is no longer the privileged object of analysis but the relation between the artist and the local community is the starting point for the critical analysis of the project. Kester talks about “the close investigation of specific projects, the ways in which power and resistance operate through a manifold of aesthetic, discursive, inter-subjective and institutional factors”.[11]

There is to be a movement toward the contexts and forms of collaboration that characterize socially engaged art. Therefore, the art historian cannot just analyze an already produced object—a painting, an installation, a performance, etc.—inside the institution; the art historian has to go out into the field and analyze the production and reception of the artwork. Kester’s art criticism is not only a rejection of October’s work-centered structuralist formalism, but also of Bourriaud’s focus on the meeting (between artwork and spectator) and interstices that more or less always remained within the institution (in a very straightforward physical sense). The art Kester is interested in is, of course, still part of art’s relative autonomy, but it is much more process-oriented, and takes place outside traditional spaces of art like the museum and the gallery.

Kester emphasizes the global dimension of socially engaged art—it is present on all continents, he writes. Therefore, FIELD has to have a global profile and present socially engaged art from other parts of the world. This is an important expansion. October has stayed safely within the parameters of Western modernism and its complicated afterlife, as can be seen in the vexed (non)involvement with the first wave of AIDS activism and, subsequently, art concerned with identity politics and, later, installation art and relational aesthetics.[12] The absence of non-Western art speaks volumes about October’s continued Euro-centrism (many have pointed out that the reference to the Russian Revolution in the name of the journal today comes off as something of a joke if we consider the desperate commitment of Lenin and Trotsky to internationalism and global revolution). How Krauss and associates are able to reproduce a Western modernist and after-modernist art canon under the banner of the October Revolution is something of a puzzle. Unfortunately, Kester seems to be inclined to reduce FIELD’s potential criticism of Western art history to a question of the introduction of socially engaged art from elsewhere as if it is a question of geographic diversity, limiting the critical revision to an expansion of the already existing canon instead of an attempt to dismantle it.

Then, there is the question of field study and the ethnographic. Kester proposes a new cross-disciplinary art criticism that adopts anthropology’s practice of field study and participant observation and moves out of the art institution into the field, where socially engaged art takes place. The critic is supposed to go where the projects go, observing them as they unfold over time. Kester writes that the critic must “empirically” “verify” the artistic projects and their “results,” although how that is to take place remains unclear. Instead of continuing the critical analysis of the anthropological turn of politicized contemporary art, Kester proposes to expand it and apply it to art criticism, without mentioning the widespread critique of the ethnographic practice of field study that has taken place over the last thirty years. As anthropologist Tim Ingold writes, “ethnographic has become the most overused term in the discipline of anthropology.”[13] And this does not even mention the imperialist prehistory of ethnography that has always haunted anthropology, and forced it to challenge the idea of an outside, scientific researcher who uses neutral language to analyze the “raw” material gathered. Kester, of course, does not apply ethnography to art criticism uncritically, but he is not very clear in his description of the new critical field analysis. Therefore, it remains uncertain what the project is supposed to do, and for whom.

Kester describes the new trans-disciplinary field study in which art history mimics or becomes—it is not fully clear how far Kester wants to go; he does not seem to want to invent an anti-discipline like Cultural Studies; it is more a question of updating the critical or historical analysis of socially engaged art—anthropology or sociology, he describes the new discipline as “a pragmatic analysis.” He distances himself explicitly from October and October-derived positions—what he defines as “the contemporary avant-garde” that, according to Kester, works with “a hypothetical spectator,” who is presumed to be unknowing and, thus, has to be made conscious and transformed by the artist or the artwork. Kester is fighting on two fronts. On one hand, he is launching a critique of modernist autonomous art in which the strength of art is located in its distance to life. On the other hand, he is trying to distance himself from the confrontational and totalizing gestures of the avant-garde, which rejects limited gains and solutions. According to Kester, despite their differences, the two practices or ideologies operate with the same condescending view of the spectator. For both modernism and the avant-garde, the spectator is a problem, the spectator is “embedded” in conformity and to be brought out of his/her docility by the artwork or the artist forcing him/her into action.[14] Socially engaged art has a different approach to the spectator, Kester argues, in that it does not stage the spectator as conformist or lacking in knowledge. The ethnographic turn is, thus, also a movement away from the hypothetical spectator of the avant-garde to the actual people of socially engaged art. The critique of the avant-garde or modernist spectator is highly relevant even though it is somewhat abridged, and the “founding” contradictions that support this paradoxical spectator are not addressed. The simultaneous negation and embrace of the spectator—culminating with the avant-garde in which the masses are a passive but potentially revolutionary collective subject—are, of course, related to modern art’s constitutive paradox: as a modern phenomenon, art is equipped with relative autonomy and embedded in a broader process of differentiation characterized by autonomy. From German Romanticism through Critical Theory and onwards toward the Situationists, we have different attempts to describe this ambiguity. Two of them will have to suffice here: In the 1930s, Herbert Marcuse wrote about the “affirmative character of culture,” that the artwork shows an image of a different world but simultaneously confirms this world and, thus, functions as a “safety valve”; in the late 1960s, Mario Perniola described art as the only permitted form of creativity in capitalist society, a limited and separate form of creativity and freedom without practical consequences.[15] Kester seems uninterested in this duality, which has to do with art’s institutional status. It is almost as if Kester believes that by physically moving outside the traditional spaces of art, socially engaged art also escapes the conceptual space of its institutions or, at least, that there is some kind of qualitative transformation taking place for which the critical field analysis must account. There are no doubt some interesting things going on here, but the “original” double-ness is always there, questioning the individual artwork’s ability to effect real change.

One of the problems with Kester’s new socially engaged art criticism, which mimics to a large extent the practice of socially engaged art, is its reliance on an adjusted Habermasian notion of communication in which dialogue leads to empathy and recognition (of the other). The critic should not focus primarily on the formal aspects of an artwork but, instead, report with empathy and evaluate socially engaged art’s ability to listen to the context and the audience. It is about establishing an “empathetic identification” between artists and their collaborators.[16] There is a problematic privileging of consensus and intersubjectivity here that tends to recoil from more radical or “unreasonable” demands that are less interested in establishing a dialogue or empathy than in making visible processes of exclusion and lines of fracture that do not disappear because the artist (and the critic) have good intentions and wish to mobilize a local community.

In a recent text from 2015 entitled “On the Relationship between Theory and Practice in Socially Engaged Art”, Kester refers to Critical Theory and zooms in on the shift that, according to him, occurred in the Frankfurt School from the beginning of the 1930s to the period after World War Two. According to Kester, the cross-pollination of empirical analysis and theoretical production that Horkheimer described in his 1931 inaugural lecture, “The Present Situation of Social Philosophy and the Tasks for an Institute for Social Research” [“Die gegenwärtige Lage für Sozialphilosophie und die Aufgaben eines Institut für Sozialforschung”], deteriorated into “sterile functionalism.”[17] According to Kester, Critical Theory abandoned empirical analysis and turned into a distant theoretical project: “Confronted with the failure of the proletariat to unite in opposition to fascism and the emergence of a ‘totalized domination’ that made the capitalist, fascist and communist state systems virtually indistinguishable (at least to Adorno and Horkheimer), the germ of an authentic revolutionary drive had been transferred to the sequestered realm of fine art.” As Russell Jacoby, among others, has described, we are dealing with a very complex process historically, politically, and theoretically.[18] But Kester’s analysis moves quickly, and disregards the substantive historical transformations taking place during these decades. Kester does not deal with the historical development from the revolutionary take off in the years between 1917 to 1923: the preventive (Italian Fascism) and the “finishing” (German Nazism) counter-revolutionary derailment of the revolutionary offensive in Western Europe, the state-capitalist counterrevolution in the Soviet Union, to the economic crisis and the anti-Fascist fight, World War Two and “the massacres of the slaves of capital,” as Amadeo Bordiga calls it, as well as the reconstruction of the apparatus of production in Western Europe after the end of the war, which resulted in high profit rates and the narrowing of the political horizon within the framework of the Cold War. This is a process in which the Western European working class movement inscribed itself in nation-state democracy, abandoning the last gasp of revolutionary demands for political rights and access to commodities and welfare.[19] Critical Theory was actually trying to analyze this development (as were the Situationists and, later, Cultural Studies) in which working class identity and culture were gradually dissolved and replaced by new image-driven subjectivities devoid of political agency. To analyze this development as a question of abandoning empirical analysis is simply inadequate.

Notes

[1] Nicolas Bourriaud: Relational Aesthetics [Esthétique relationelle, 1998], translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les presses du reel, 2002).

[2] Cf. Claire Bishop: “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics”, in: October, no. 110, 2004, pp. 51-79. Other very critical interpretations include Hal Foster: “Arty Party”, in: London Review of Books, December 2003, pp. 21–22. For an attempt at a more nuanced reading, see: Stewart Martin: “Critique of Relational Aesthetics,” in: Third Text, vol. 21, no. 4, 2007, pp. 369–386.

[3] Cf. Lucy Lipard: “Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power”, in: Brian Wallis (ed.): Art after Modernism: Rethinking Representation (New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art & David R. Godine, 1984), pp. 342-358.

[4] Grant Kester: Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004). See also the following book, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011) in which Kester expands his analysis of socially engaged art.

[5] Ibid., p. 7.

[6] Brian Holmes: Unleashing the Collective Phantoms: Essays in Reverse Imagineering (New York: Autonomedia, 2008).

[7] Gene Ray & Gregory Sholette: “Introduction: Whither Tactical Media,” in: Third Text, vol. 22, no. 5, 2008, pp. 519-524.

[8] Walter Benjamin: “The Author as Producer” [“Der Author als Produzent”, 1934], translated by Anna Bostock, in: Essays on Brecht (London: Verso, 1998), pp. 85-103.

Yates McKee’s new book, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (London & New York: Verso, 2016), is an impressive attempt at analysing the artistic dimension of Occupy or contemporary art as post-artistic protest art.

[9] In many ways, Documents was the U.S. equivalent to the French Documents, edited by Bourriaud and Eric Troncy. It is interesting that the early 1990s were characterised by an explosion in the number of non-commercial art journals that all competed in different ways in developing an art critique able to account for the new artistic practices that emerged at the time. In France alone, we have Documents, Purple Prose and Art Bloc Notes. Interestingly, the driving forces behind the two later journals ended up in the fashion industry. In the US, the other important early 1990s journal related to the new generation of institutional critique was Acme Journal, edited by critic Joshua Decter and artist John Miller.

[10] Grant Kester: “Editorial”, in: Field: A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism, no. 1, 2015, online: http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/issue-1/kester

[11] Ibid.

[12] One of the best examples of the difficulties October has had with more politicized art practices is the discussion in “The Politics of the Signifier” about the Whitney Biennale in 1993 for which there was an explicit identity political agenda. It is very difficult for Krauss to accept the inclusion of a clipping from a newspaper article with a quote by the African-American mayor of Los Angeles about the Rodney King incident in Lorna Simpson’s installation “Hypothetical?” because, according to Krauss, it short-circuits the meaning of the artwork and reduces it to a question of “black rage”. See “The Politics of the Signifier: A Conversation on the Whitney Biennale”, in: October, no. 66, 1993, p. 5.

[13] Tim Ingold: “That’s enough about ethnography!”, in: HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, p. 383.

[14] Kester’s criticism of the alienated spectator of modernism and the avant-garde, a spectator who has to be provoked by the conscious artist resembles Jacques Rancière’s analysis of the “emancipated spectator”. However, Kester does not refer to Rancière. In an interview in 2006, Kester wrongly identified Rancière with an avant-garde position even though Rancière explicitly dismissed the avant-garde and criticized Debord and the Situationists for looking at the spectator as blinded or alienated. That Kester gets Ranciére wrong in this way probably has something to do with the reception of Rancière in (Anglophone) contemporary art in which, for instance, Claire Bishop has referred extensively to Ranciére in her critique of Kester in which she faults him for a failure to address the aesthetic dimension of art. That Bishop effectively uses Rancière to downplay art’s anti-institutional and anti-capitalist dimension only makes things worse. Part of the problem has to do with Rancières own fairly fussy description of art’s meta-political dimension (an expansion and supplement to his earlier description of the meta-aesthetic dimension of politics) in which modern art is characterized by the ability to use and thematize everything, making everything the object of aesthetic appreciation. That way, modern art has a utopian potential to show a different “sharing of the sensible”, to show a different world. Rancière’s fine re-reading of the dual character of art unfortunately stops there, forcing him to reject the avant-garde’s anti-artistic and revolutionary experiments.

[15] Herbert Marcuse: “The Affirmative Character of Culture” [“Über den affirmativen Character der Kultur”, 1937], trans. Jeremy J. Shapiro, in idem: Negations: Essays in Critical Theory (London: Mayfly Books, 2009), pp. 65-98; Mario Perniola: L’alienazione artistica (Milan: Mursia, 1971).

[16] Grant Kester: Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art, p. 150.

[17] Grant Kester: “On the Relationship between Theory and Practice in Socially Engaged Art”, in: A Blade of Grass, 29 July 2015, online: http://www.abladeofgrass.org/fertile-ground/between-theory-and-practice/

[18] Russell Jacoby: Dialectics of Defeat: Contours of Western Marxism (London & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

[19] Amadeo Bordiga: “War and Revolution” [“Guerra e rivoluzione”, 1950], online: https://libcom.org/library/war-revolution-amadeo-bordiga

[20] Leo Bersani coined the phrase “culture of redemption” to account for theories that want art to redeem life (but end up demeaning both art and life). The Culture of Redemption (Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[21] Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen: “Scattered (Western Marxist Style) Remarks on Contemporary Art and its Difficulties”, in: Third Text, vol. 25, no. 2, 2011, pp. 199-210.