An Interview with Michelada Think Tank

Noni Brynjolson

Michelada Think Tank is a collective of artists, educators, and activists who organize conversations around issues facing people of color, in the art world and in the communities in which they live and work. Noé Gaytán, Mario Mesquita, Shefali Mistry, and Carol Zou met at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, and later connected with Dallas artist and activist Darryl Ratcliff. One of the collective’s first interventions was investigating the demographics of the 2014 Open Engagement conference in Queens, New York. They used this information to raise questions about racial disparity and cultural representation throughout the art world and in higher education. While “Think Tank” connotes seriousness and criticality, the collective’s events are meant to be lively and engaging — serving micheladas helps to lighten the mood and get the conversation flowing (their recipe: Tecate, Clamato, and Tajin, plus lots of lime juice and hot sauce). In this interview, they speak about the work they’ve done over the past few years, how they position themselves in relation to social practice, and their current exploration of cultural equity as artists-in-residence at the San Diego Art Institute.

NB: Most of you met in Otis’s Public Practice MFA Program, and you’re now living in different cities across the United States. I’m curious about the local, specific issues associated with the neighborhoods and communities where you live — how do these relate to broader issues of racial inequality that inform your work?

MTT: It is incredibly helpful for us to be in contexts that give us a comparative perspective on our work for racial equity. As we convene Think Tanks in different cities, we know there is a lot of overlap in issues that artists of color face. The contextual difference is in each city’s arts infrastructure or ecosystem that produces these challenges and potential solutions. Because we are in different cities, we are able to exchange strategies for organizing for racial equity on both a localized and national level.

NB: One of the factors that led to the formation of Michelada Think Tank was the 2014 Open Engagement conference in Queens, NY, where you distributed a postcard that listed racial disparities in the demographics of presenters. What do you think has come out of this action? Do you think it had an impact on the conference in terms of its organizational structure, presenter demographics, thematic focus, or conversations?

MTT: We definitely saw a change in Open Engagement after our 2014 intervention. In 2015, Open Engagement self-released their demographics in their conference publication and invited us to host Think Tanks during the duration of the conference. However, most attendees of the conference were still predominantly white, and this was pointed out by the artists of color who packed our Think Tanks seeking a safe space.

In 2016, it seemed like the demographics of the conference would shift favorably because of the conference’s siting in Oakland and because of Angela Davis as the keynote speaker. However, when we reached out again to Open Engagement for demographics, they were unresponsive. We then learned that several key Bay Area cultural organizations, such as Favianna Rodriguez of Culture Strike, had been excluded from planning and even speaking at the event. We were able to get the demographics through other presenters, but when we released the demographics (which tallied the conference presenters as 51% white), Open Engagement released a statement saying that the information we circulated was incorrect. Which is weird, because we were using numbers that the organizers had emailed the presenters. Either way, to say that a conference was only 51% white (or 45%, according to the revised official demographics) is a pyrrhic victory. It still means that white presenters are overly represented at the conference; they just perhaps are not as overly represented as they were before.

I think this is reflective of a crisis in social practice in which it needs to separate itself as a separate field from cultural organizing, which is a field that includes many more people of color. Allied Media Conference in Detroit comes to mind as a cultural organizing conference that is organized and attended by predominantly people of color. But in creating this separate space called “social practice” and excluding cultural organizers such as Favianna Rodriguez, it creates a space that is highly racialized.

NB: The model of the Think Tank brings up the role of research and data, and suggests an objectivity that aims to either compete with or satirize the bureaucratic language of large cultural institutions. In this regard there are some similarities to institutional critique in the 1970s and 80s. Would you place your work in this tradition?

MTT: Our work satirizes the Think Tank by mixing the Think Tank format with a social lubricant, micheladas! In the spirit of Ghana Think Tank, we also critique the ways in which Think Tanks are often comprised of conclusions from white “experts” instead of ideas from grassroots people of color. Ironically, however, our “Think Tank” designation has allowed people to view us with more legitimacy than we perhaps have or even prefer to confer upon ourselves. We have been unwittingly placed into the role of being experts on cultural equity, while working with this form that critiques a traditional understanding of Think Tank expertise.

NB: How might it be an update or revision of institutional critique?

MTT: We definitely place ourselves within this tradition, but we are also self-aware that artistic communities of color exist outside the institution, so our work carries this tension between institutional critique and grassroots organizing. Part of our work is also turning a critical lens on the institutions and organizations we work with. At Otis we were invited to create a lobby display and we took the opportunity to point out the discrepancy between student and staff diversity. During our residency at LACE we dedicated a wall of the Project Room to examining the demographics of artists who had exhibited at LACE since their inception. We believe this practice is important for us to maintain our autonomy from whomever we partner with.

NB: The events that you organize tend to be open-ended, and they frequently center around conversation, dialogue, and group brainstorming. Can you speak about the format of these events and how it was developed?

MTT: After our initial intervention at Open Engagement 2014, we discussed our challenges as artists of color and the type of space that we wanted to create to support artists of color. We realized that being in a convivial space in which we could share our challenges with each other was one of the most valuable aspects of our collaborative relationship. That’s when we decided to focus our work on creating a safe social space for artists of color. At the same time, we didn’t want our social space to devolve into people coming with complaints but leaving without solutions. We try to guide our conversations around different topics in order to build upon our shared knowledges and generate actionable steps. Often we are the convening agent, but we find that we are most successful when people are energized by the conversation in order to initiate their own contribution towards racial equity. For example, one person who attended our Think Tank decided to initiate an artist network for artists of color. We understand that we can’t achieve racial equity on our own; the discursive nature of our events creates spaces for others to workshop their ideas, meet collaborators, and contribute to a larger movement.

NB: Recently, many large cultural institutions have embraced socially engaged practices and have sought to engage with so-called marginalized communities or communities of color. What are your thoughts on these kinds of “outreach” programs?

MTT: But how many of those “outreach” programs exist within the education department though! We definitely advocate for more inclusion in cultural institutions when it comes to artists and audiences. However, the onus for inclusion is often placed on the shoulders of the education department. For some institutions, not all, it seems like they are just fulfilling a diversity quota but not invested in significant institutional transformation. We advocate for transformation and equity in all departments of institutions — curatorial, development, administration, education, etc.

NB: How do you feel about working within institutions to reshape their priorities, versus acting outside of, or resisting institutional frameworks?

MTT: That’s a tricky question on which we have been challenged. However, we are all self-aware of our complicity as artists with MFAs and BFAs. For us, it would be hypocritical to deny the institutional access that we have and act like we only exist in marginal spheres outside the institution, which is blatantly untrue. Instead our strategy is to utilize our institutional access and educational privilege to create more opportunities for access and mobility, especially taking into consideration the voices of people who may not have the same types of institutional access that we do.

NB: In thinking about art practices that might be referred to as activist, what role do you think cultural organizing plays in terms of broader conversations about racial inequality? Do these conversations have the potential to move outside the realm of art, in your opinion?

MTT: I think we’re living in an interesting moment in which the most important cultural practices, such as the work of #BlackLivesMatter, are happening outside of museums and then are invited back into the museum. For example, MOCA Los Angeles recently invited Patrisse Cullors and Tanya Lucia Bernard from #BlackLivesMatter for an event, just one year after the controversy over Edie Fake appropriating the #BlackLivesMatter slogan for the LA Art Book Fair that was also held at MOCA. But then again, many community arts and activist practices are just now being reabsorbed into the museum under the aegis of “social practice.” Perhaps the question is not whether or not these conversations can move outside the realm of art, but whether or not existing cultural organizing practices can move inside the art world.

NB: What do you plan to work on during your residency at the San Diego Art Institute?

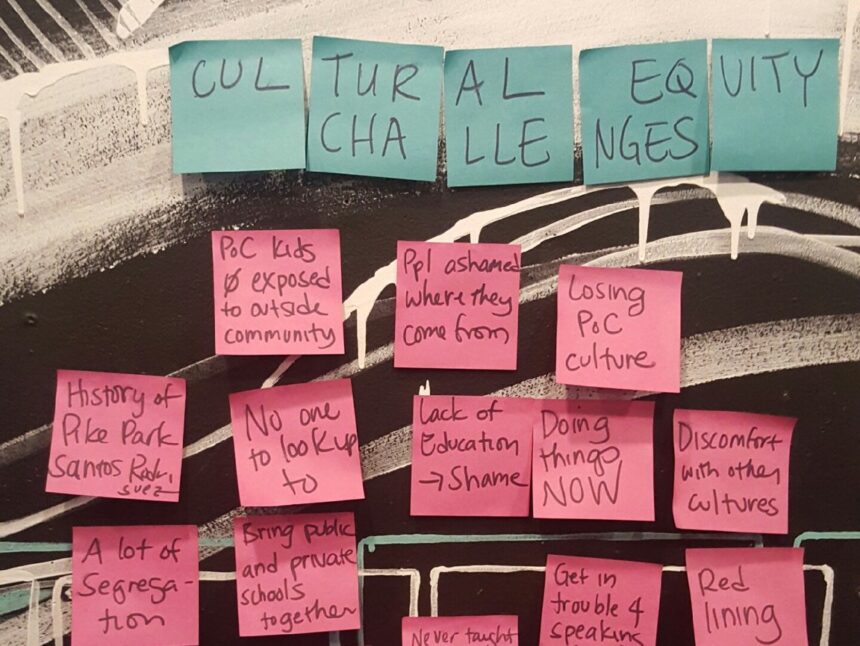

MTT: We will be convening one large forum and two smaller forums to discuss a number of topics that came up during our initial planning session with artists, community organizers, and writers of color in the San Diego area. We will then host a culminating event with our findings and recommendations. The topics that we have chosen to discuss are geographic factors (including gentrification, the border, and San Diego’s relationship to Los Angeles), civic engagement and collaboration, critical archiving of local history, occupying spaces in arts institutions (representation), and then the academic art world versus community arts.

Some of these topics overlap with topics that we have explored in Los Angeles and Dallas, and some are unique to San Diego, such as the geographic factors. This is also the first time that we have not worked in a person of color majority city, so it will be interesting to rethink the needs of artists of color in that context.

Michelada Think Tank (Noé Gaytán, Mario Mesquita, Shefali Mistry, Darryl Ratcliff, and Carol Zou) is a multi-state group of socially conscious artists, educators, and activists of color hosting conversations with other people of color (PoC) and allies who are interested in creative ways of making change happen. MTT is interested in facilitating conversations and creating community around issues faced by people of color while promoting action beyond the discussion. Initiated in Los Angeles, MTT grew out of a need for artists of color in an MFA program to support one another, and quickly realized the issues faced in graduate school were similar, if not the same, to issues artists of color face outside the context of the educational institution. MTT is now in Los Angeles, San Diego, Dallas, and New York.

Noni Brynjolson is a PhD Candidate in Art History, Theory and Criticism at the University of California, San Diego.