Merciless Aesthetic: Activist Art as the Return of Institutional Critique. A Response to Boris Groys.

Gregory Sholette

“The phenomenon of art activism is central to our time because it is a new phenomenon.”

Boris Groys “On Art Activism”[1]

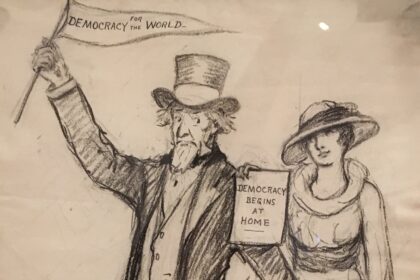

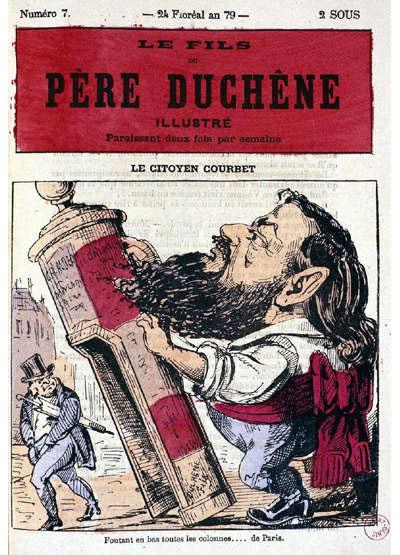

On the face of it, Groys is making an extraordinary claim. Doesn’t he and everyone know by now that art activism has a solid backstory brimming with risks and minor victories, compromises and outright failures, just the same as any other cultural narrative, even if this one remains largely closeted within mainstream art history? [2] Consider Jacques-Louis David’s elaborate public floats designed by the painter for public fêtes to rally support for the French Revolution in the 1790s. Or less than a century later Gustave Courbet’s decisive role in the dramatic toppling of the militaristic Vendôme Column during the Paris Commune, an action that also coincided with the development of mass-produced photographic images that transformed this spectacular event into widely circulated cartes postales. More recent examples include the pageant of black body bags carried by members of Art Workers’ Coalition up Fifth Avenue to protest the Vietnam War in 1969, or members of Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG) with the same agenda staging a mock gunfight in front of Museum of Modern Art in May of 1970. Then there was a storm of satirical billboard alterations denouncing US intervention in Latin America in the early 1980s, and the rise of Tactical Media ‘image correction’ and ‘digital civil disobedience’ campaigns carried out by Electronic Disturbance Theater, Critical Art Ensemble, and RTMark in the 1990s, followed of course by The Yes Men, YOMANGO and The Illuminators among others. In each case activism and cultural production (and sometimes cultural destruction) shared a stage together, though in many instances these practices have avoided being labeled as art, sometimes rejecting this term outright, or identifying with it primarily in order to yield specific benefits. Even then, dallying with the world of museums and galleries remains a delicate, tactical operation. However, as Groys observes, this indifference towards the art establishment no longer applies to activist and socially engaged practices today. His species of art activism — for there is more than one — is designated by its familiarity with the art world, its willingness to court it or make use of its resources (while also sometimes loathing it). [3]

Examples abound, though here I note three:

“We see our proximity to the system as an opportunity to strike it with precision, recognizing that the stakes far exceed the discourses and institutions of art as we know them.” [4]

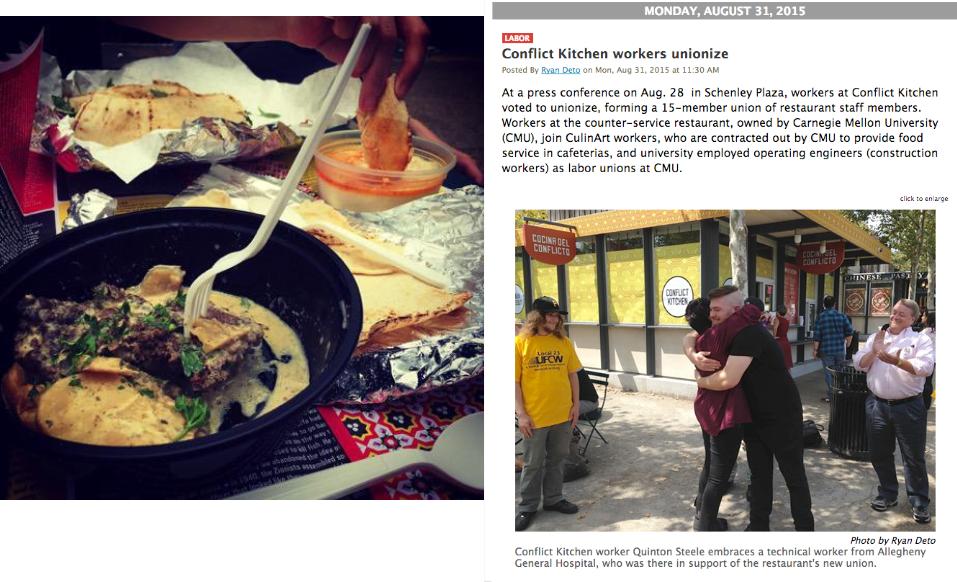

All three projects position themselves differently in relation to the field of art, though all three do so consciously, even programmatically. While the project in Berlin challenges the art world’s opacity, it outmaneuvers government authorities thanks to the peculiar “license” of mimetic artifice that only art affords. Meanwhile, in Pittsburgh, art’s privileged autonomy is taken as a baseline even as the food project more and more collides with exogamous non-art social and juridical realities such as self-organizing workers and legal actions. In example number three it is art’s institutional power that is judiciously leveraged in order to make a political statement, but the statement is not about the working conditions of artists, it is about precarious laborers in the Middle East. As Groys acknowledges:

“Art activists do not want to merely criticize the art system or the general political and social conditions under which this system functions. Rather, they want to change these conditions by means of art—not so much inside the art system but outside it, in reality itself.”

Perceptively he points out this recent wave of art activists “wants to be useful, to change the world, to make the world a better place—but at the same time, they do not want to cease being artists.” (My italics.) And therein lies the rub.

Nothing drives serious cultural scholars off the rails quite like artists asserting their essential categorical indeterminacy. Artists wish to be both a particle and a wave, just like light. How does it go? I am an artist only when I must be, such as when I apply for grants or for a teaching job or when a museum shows my work. Conceptual artists may have opened the door to this ontological evasiveness in the 1960s when they stated that they were going to serve as their own art critics and theorists, or when they presented mathematical equations as art, or performed music instead of having exhibitions, or just dropped out as Lee Lozano claimed to have done “in order to pursue investigations of total personal and public revolution.”[5] The mainstream took a very long time to accept any of this as “art,” and still today remains uncomfortable with artists who do science experiments instead of making paintings and sculpture, or who engage in political activism instead of performing, or god forbid artists who practice both activist art and science together as Critical Art Ensemble did and were punished for in the recent past.[6] It gets weirder. Contemporary art appears to freeze and liquefy, to freeze and liquefy again, undergoing phase changes that, as artist and theorist Melanie Gilligan suggests, resemble finance derivatives, infinitely re-moldable while nonetheless dependent “on the reorganization of something already existing.”[7] Or as Stephen Wright maintains, contemporary art has simply left the room altogether. In his book Toward a Lexicon of Usership the theorist informs us art is moving beyond the realm of representation into a 1:1 correspondence with the real world.[8] What to make of this? Recall the fourteen improbable classes of animals in Jorge Luis Borges’ fictitious Chinese encyclopedia The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge: Stray Dogs, Embalmed ones, Fabulous ones, Et cetera, “Those that are included in this classification,” and Suckling pigs, among other ill-matched categories.[9] Yet even this fantastical attempt at reconciling a multiverse of possibilities, definitions and contradictions are easier to accept than the reality of contemporary art.

The same holds true for art as political action. “The inexplicable pleases us, and the incomprehensible is our friend,” Nadya Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot cites the dissident Russian poet Alexander Vvedensky.[10] But couldn’t we easily resolve this riddle if we say that this new wave of artistic activism simply does not wish to foreclose on the privileges provided by contemporary art in the 21st Century? It’s all a matter of pragmatics. Certainly, we could explain it away like this, dismiss it as self-delusion, except that this is not what Groys is suggesting, and I find myself in agreement. As Pussy Riot member Tolokonnikova put it in her courtroom speech prior to being sentenced for the group’s punk art intervention in the Church Christ The Savior: “What Pussy Riot does is oppositional art or politics that draws upon the forms art has established.”[11] These are trained cultural practitioners who make art as politics, or vice versa. Not surprisingly, admonishments come down from many quarters.

There are of course well-rehearsed arguments previously proposed by theorists Walter Benjamin and Guy DeBord warning us to stand vigilant against aestheticizing politics, as opposed to politicizing aesthetics or artistic production. Groys has a lot to say here and we will return to this shortly. But there is also an incredulous reprimand that comes from the opposite side of the “art and politics” spectrum, that is to say, not from the world of high culture, but from activists themselves. As much as these very activists often quietly admire artists for their singular claim to human freedom and self-directed labor, they also harbor more than a little skepticism about the privileged field of contemporary art. Too often the liberty of artists comes at the expense of those located even lower down in the social pecking order. This suspicion towards the art world also exists amongst activist image-makers and artists who consider themselves first and foremost an organic part of a given political struggle. Let me start here with the voluminous imaginative productivity of activists that Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee call social movement culture. [12]

Unlike mainstream art whose canonical standards and criteria of judgment rest on centuries of institutional practices, social movement culture defines itself as emergent from within the composition of political movements.[15] In other words, the posters and graphics and other frequently ephemeral and time-specific imagery generated by activists are like so many cells generated and then shed by a body in motion. This is quite the opposite of autonomous art forms that first and foremost embody sensual expressivity, formal investigations, or aim to stimulate reflexive contemplation.[16] Not only does this definition of social movement culture suggest that the artifacts it produces resemble those auratic objects Benjamin famously predicted would vanish in an age of mechanical reproduction, but it also means that the more this movement culture is disconnected from its service in action, the more it begins to appear as, well, as just ‘art,’ and therefore less like social movement culture. This internalized fidelity to what Adorno would decry as a heteronomous agency and extra-cultural interests located outside of art’s proper boundaries has profound implications.

“Striking art means liberating art from itself, and in turn recognizing that collective liberation always has an aesthetic dimension, understood not as an ideal image of harmonious identity but rather as an activity of dissensus that never comes to an end.” (242)[22]

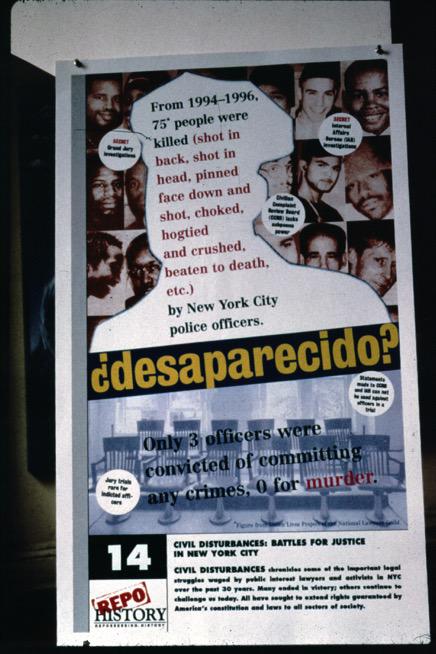

Then again, it might simply be the case that Groys’ declaration of activist art’s novelty signals the fact that it has reached a level of visibility not even established critics (such as Groys) can ignore any longer? But surprise: in the late 1980s and early 1990s politicized art became similarly conspicuous. The Dia Art Center, Museum of Modern Art and The Whitney Museum all mounted exhibitions about art and politics that appear in retrospect to have been a measured response to the far broader level of cultural activism taking place amongst primarily younger artists who made up such collectives as Group Material, Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D), Guerrilla Girls, and Gran Fury among others.[23]

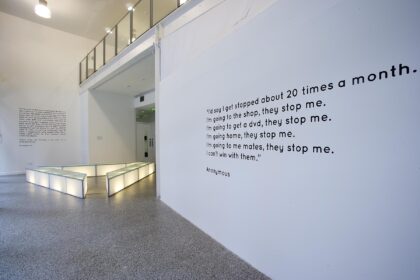

Still, I find myself again strangely agreeing with Groys, at least in so far as sharing his recognition that the phenomenon of artistic activism is indeed growing, is indeed more and more visible, and is indeed doing so in evidently unfamiliar ways. We are witnessing an international explosion of direct social art interventions seeking to improve the actual material conditions of laborers, migrants, stateless people, prisoners, people of color, the homeless, interns and unpaid art laborers, as well as efforts to protect the natural environment against ruin. Few of these concerns are directly relevant to high culture’s own institutional problems (except significantly the question of artistic labor). Groys finds this noteworthy. So do I. For one thing, this new surge of art activism is different from a certain type of critical art that has as he points out “became familiar to us during recent decades,” as Groys says. No doubt the reference is to the practice of institutional critique about which even Andrea Fraser admits has become today a “victim of its [own] success or failure, swallowed up by the institution it stood against.”[24]

But there is still another, deeper layer of suspicion that separates activists from artists. It is a discord that rests at the dead center of Groys’ argument. And it is the means by which he claims art activism is a “new phenomenon,” although, as we shall see, it is ultimately nothing more than a return to the familiar form of critical art after all. “Art,” he insists,

“cannot be used as a medium of a genuine political protest—because the use of art for political action necessarily aestheticizes this action, turns this action into a spectacle and, thus, neutralizes the practical effect of this action,” according to Groys.

Once Groys establishes that art for arts sake overturned all previous mandates insisting high culture serve the State, Church or Aristocracy, and thus turning all past ideological and cultural instruments of power into functionless objects of pure contemplation, then the obvious question is raised: what sort of conditions would need to be present today in order to release this same art-power against modern, 21st Century human rights abusers and corrupt political regimes? And voilá, we already have our answer. Total aestheticization generates for the status quo “a much more radical form of death than traditional iconoclasm.” Who could have imagined that in centuries later the old enlightenment ideal of purposeful purposelessness could be resurrected as a hard-hearted weapon against a corrupt world? Someone should tell ISIS! And presumably by extension total aestheticization would also be far more politically and critically effective than all that messy well-intentioned social movement culture and Occupy DIY art combined. Forget about vitriolic caricatures of authoritarian politicians and cardboard graphics, the bobble-headed banker marionettes, New York Times parodies and uproarious Yes Men Survivaball antics, none of these could ever truly compete with the democratizing effect brought about by death from total aestheticization.

“Every action that is directed towards the destruction of the status quo will ultimately succeed. Thus, total aestheticization not only does not preclude political action; it creates an ultimate horizon for successful political action.”

And we are back where we started. Total aestheticization permits the seemingly assimilated practice of institutional critique to be reborn as activist art.

— 2 —

“Using the lessons of modern and contemporary art, we are able to totally aestheticize the world—i.e., to see it as being already a corpse.” — Groys

But hold on, hold on. What if total aestheticization is not the result of some necrotic art-ether leaking out into the actual world, some deadly contaminant spewed from the citadel of revolutionary modernism and contemporary art? What if instead it is exactly the opposite: the rushing inwards of a previously overlooked creative productivity (and sometimes non-productivity): including that of the amateur, the informal artist, the social movement artist, all those redundant energies generated by the everyday and even banal imaginings of everyman and everywoman now occupying the space that art once held apart from society? It might be compared to the sudden unblocking of what Alexander Kluge and Oscar Negt once described as the counter-public sphere: a realm of working class fantasy just below the surface of productive disciplines aimed at negating the alienating conditions of capitalism.[27] Or we could refer to this process as the illumination of a previously hidden creative mass or artistic “dark matter” consisting of informal acts of everyday resistance, as well as resentments, both of which are necessary for the reproduction of the institutional art world.[28] It is an aestheticization from below that drags with it all manner of things, including both politically correct and reactionary ideas and images and affects, pop-cultural garbage and advertising schemes, sentiments, militancy, bathos, nostalgia and racism. It is like a carnival of attractions or Borges’ Chinese encyclopedia, messy and impure and excessive, but it comes with its own means of survival. John Roberts recently described the vast yet marginalized sphere of non-market activity as art’s “second economy.”[29] And it’s also egalitarian to an extreme. After all, any kid today with a 3D printer can be a Jeff Koons tomorrow. In truth this trouble from below has been ongoing far longer than the present wave of art activism suggests, though what most distinguishes this current occupation of art and aesthetics is its very composition: the armies of angry, pre-failed MFA students, the self-organizing, unwaged art laborers, including especially those who have recently been woken up by Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados Movement, Black Lives Matter. If art activism is a new phenomenon then it is as much the result of the 2008 financial collapse and the ongoing predicament of global capitalism in general as it is a turn outward of art world aesthetics. Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F.) makes the link explicit,

“Wall Street is an abstract space, everywhere and nowhere at once. By de-occupying it, we created space for collective powers to surge forth and for struggles to connect with one another. Walking together, we have asked questions. How do we live? What is freedom? What does solidarity look like? What role can art play?”[30]

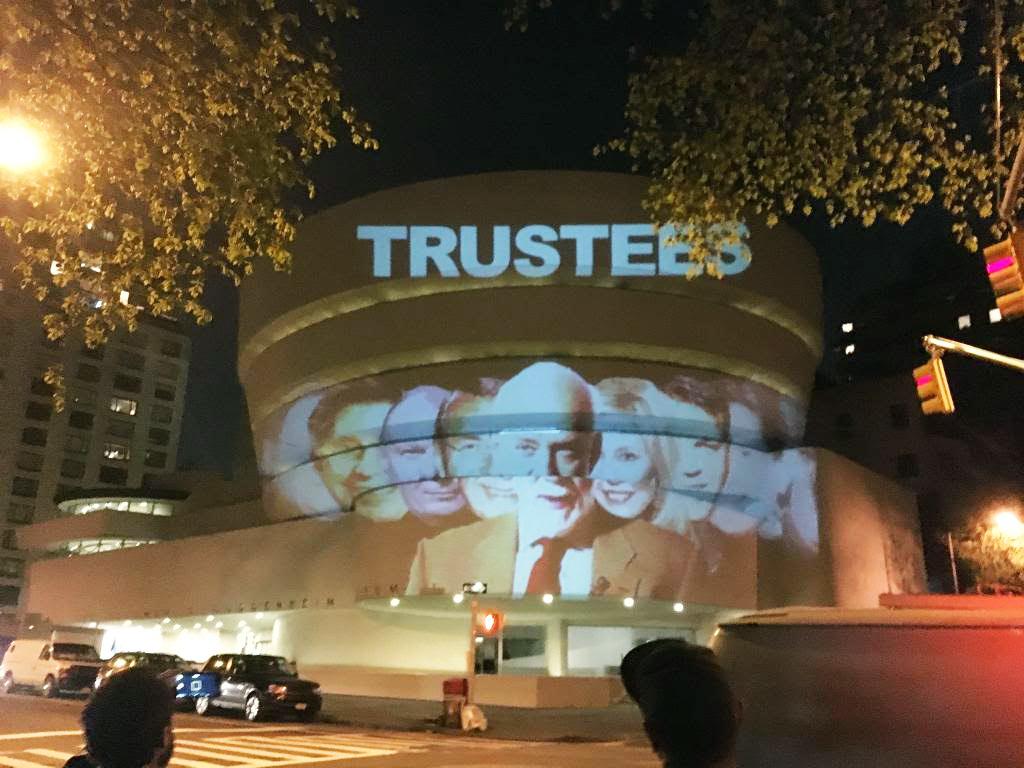

G.U.L.F. answers its own question by dramatically occupying the Guggenheim Museum on May Day 2015 in New York City, and then again a week later in Venice, Italy during the 56th Venice Biennale All the Worlds Futures organized by Okwui Enwezor. Both actions sought to call attention to the plight of migrant labor in Abu Dhabi where the museum is in the process of constructing a new contemporary art museum.[31] If Wall Street is an ubiquitous abstract space, then so too is the realm of high culture as well. It sits at the nexus of capital, art and cheap precarious surpluses of overabundant labor. All of which makes it possible for artistic production to once again be at the center of a struggle over definitions and possibilities not only regarding what might constitute a genuine avant-garde practice – something perhaps achievable only through its very denial – but also about the nature of creativity, democracy, political agency, public space and perhaps even revolution. It is not artistic ideals or critical theories but capitalism itself, with its seemingly endless destructive-creativity, that spurs the total spectacularization of everything. Capital annihilates space through labor-saving technologies and ultra-fast financial transactions. Of course modern aesthetic theory played its part in this breaching event. But when Groys focuses on Benjamin’s invocation of Klee’s Angelus Novus who he writes “moves into the future—but backwards,” and then concludes that this image represents a “U-turn on the road towards the future,” we do not have to reject Benjamin’s deep suspicion of historical progress in order to invoke a different reading. The German philosopher’s call to politicize art asks committed practitioners to focus on the radicalization of culture’s means of production, thus bringing art into closer proximity with the actual, continually evolving imaginary of the working class, as well as nearer to an encounter with “now-time,” or jetztzeit, a moment ripe with revolutionary possibilities.[32] And for better and sometimes for worse, that imaginary is where the “2 Rs” of resistance and ressentiment animate social movements on the Left as well as the Right.

— Coda —

“The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.” Karl Marx [34]

I am trying to forget the many debates we endlessly engaged in back in the 1980s: art versus activism, politics versus aesthetics, representation versus direct action, all those many disputes built on the unresolved wrangling of previous generations that was our inheritance from such collectives as Angry Arts, The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, Art Workers Coalition, Guerilla Art Action Group, and Artists Meeting for Cultural Change to mention only a few of these informal factions of the 1960s and 1970s. I am trying to avoid activating the pre-programmed subroutines and definitions that kick-in for me whenever “art” and “activism” appear together in a sentence such as this one. I am therefore attempting a cold, grey-matter reboot based on the ludicrous assertion that art activism is a new phenomenon. After all, my own ruminations in the dark archive of art’s missing mass have not always been entirely positive; my findings not always progressive or politically healthy. I will perform this scholarly misdeed by actively forgetting four decades of accumulated research, writing and politically engaged art practice. First proposed by Friedrich Nietzsche and elaborated upon by Jacques Derrida among others, active forgetting is the tactical withdrawal of memory that simultaneously erases and makes legible the archive and its feverish hold over us.[35] But make no mistake, my conduct unbecoming does not void the previous critique of Groys’ oversights delivered with what I hope is sufficient academic protocol above. Instead the aim now is to locate what Bruno Bosteels calls an “enabling fiction,” a transparent lie capable of restoring to the beleaguered Left its lost emancipatory imaginary.[36] How else to counter the non-stop crisis that thus far is the 21st Century? For regardless of whatever “time-honored disguise and borrowed language” a pending confrontation ultimately adopts the fateful rendezvous of liberty and barbarism seems increasingly imminent. So Спасибо Professor Groys, this is my attempt at reset:

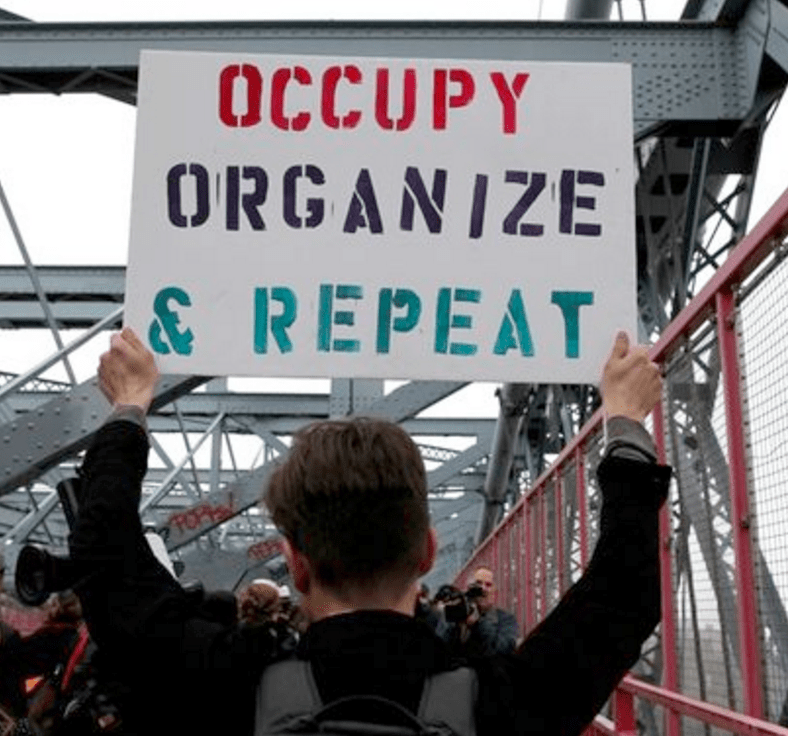

Occupy, Organize & Repeat

Art activism appears to be a “made for TV” event. Whether it seeks to raise awareness of racism, xenophobia, class privilege, or the overturning of bad government policies the implicit rationale of an action only becomes visible to most people at the moment its documentation hijacks the mass media as a news report or shareable video. Art activism, in other words, is primarily experienced only in the past tense. But what if we shift our perspective to focus on the activism of art activism? What if we view it as an event-object situated partially in the here and now, and partially in a time, place and medium still to come? [37] Like some vibrant ante-archival agency this version of direct art action interrupts the present by drawing upon its own impending futurity. And with this weird temporality in play bodies momentary bypass the routinized blockages and choreographed movements built into the very structure of corporate atriums, policed streets, privatized spaces and museum lobbies. Which is to say, perhaps the most unsettling aspect of artistic activism may not be the viral video or spectacular photograph but the moment participants and bystanders are temporarily disengaged from familiar social narratives and forced to confront their own tacit state of un-freedom.[38] Returning us to key questions posed above: does this singular event-object evade the distended institutional critique paradigm inferred by Groys, and can it slice through the historical loops of Steyerl’s Gordian knot? Yes. And no. And yes.

Regarding the return of institutional critique there is every reason to believe, following Marx, that art world intellectuals, curators and critics will continue to apply this now orthodox terminology to every cultural trend that gains visibility at any given moment.[39] However, the sublation of artistic production by the global marketplace (and ultimately by finance capital) just as all social organizations are being hollowed-out by private interests means the critique of institutions must either take aim far beyond the cultural sphere, or as Fraser opines, wallow in its own victimhood. Most activist art and social movement culture recognizes and embraces the conundrum. As G.U.L.F. affirms,

“We recognize that our work, our creativity, and our potential are channeled into the operations and legitimization of the system. We work—often precariously—as both exploiters and exploited, but we do not cynically resign ourselves to this morbid status quo.”[40]

Escaping from crisis capitalism’s “groundhog day” effect is more challenging. Even as art activism leaks the future into the present it cannot help but leak the past in along with it. After all, art activism’s very form recapitulates decades, even centuries of embodied resistance to unjust laws, exploitation and authoritarian power. Still, the activist event-object does not treat the future prescriptively by championing any specific utopian model, other than perhaps a very broad claim to this or that notion of the commons.[41] Instead, futurity enters into the present as a short-lived confirmation proving that the catastrophic repetition of time imposed by capitalism is not inexorable (even if the consequences of this demonstration are not always clear-cut or progressive). And just as capitalist time can only ever offer the eternal return of the M-C-M commodity form, art action counters with its own perennial and redundant adversarial ontologies. Under conditions of post-democratic, ultra-deregulated markets, even these very temporary scraps of resistance against disciplinary time and space are disturbing to the moribund status quo. For one thing their materiality generates spontaneous encounters with experiential knowledge via collective bodies that is quite different from the regimented training of individuals implicit within institutional spaces. This in turn has unpredictable outcomes. Some participants will experience activist art as liberating and therefore also pleasurable and possibly even motivating towards further political reflection and action. In this sense the event-object represents the possibility of a truly complex praxis that joins theory with embodied action. At the same time art activism is experienced quite differently by those wedded to the disciplinary regimes of the status quo. It may appear baffling and therefore possibly paralyzing, or more worrisome still, it might be perceived as terrifying, and thus serve as a spur for preexisting feelings of rage and resentment.

Regressive mass animosity grows in intensity today, claiming political legitimacy via the US presidential campaign of Donald Trump as well as a half dozen other chauvinist and anti-immigrant movements emerging across the developed world. These political factions are the antithesis of futurity. They seek to bring history to a close, but not in the liberal-democratic way Francis Fukuyama once famously championed following the collapse of the Cold War in 1989 as capitalism “normalized” a faltering socialist East.[42]Instead, the new “end of history” is a lot like the Far Right’s drive to eliminate all forms of governance in so far as it appeals to a near-apocalyptic mania for the total, claustrophobic monetization of daily life down to the last detail, be it public or private, singular or collective, even including the mental and spiritual dimensions of our inner existence (there are for instance technologies being developed that will profitably mine our dreams[43]). This is where activist art makes its detour towards an unknown and different event horizon quite unlike the U-turn of failed conventionality or expanded institutional critique proposed by Groys.[44] If some new aesthetic phenomenon is indeed being generated by this so-called new wave of art activism it is not found within the predictably utilitarian moment of documentation alone, but rather is embedded deep within the structure of the event itself. Like a vibrant, archival agency the activist event-object is made up of past, present and future possibilities, always already compromised, certainly, but also simultaneously brimming with probabilities and uncertainties. Which is why any new wave of art activism is not only not “new,” it is entirely new, it is a repetition of the type that can only happen once, and then once again, and then once again. Occupy, organize and repeat.

Gregory Sholette is a New York-based artist, writer, activist and founding member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D), REPOhistory, and Gulf Labor Coalition. His publications include It’s The Political Economy, Stupid co-edited with Oliver Ressler, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in an Age of Enterprise Culture, and a forthcoming book of essays introduced by Kim Charnley with a preface by Lucy R. Lippard (all by Pluto Press UK). Along with an upcoming solo exhibition at Station Independent Projects in November 2016 his recent installations include Imaginary Archive at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania and Zeppelin University, Germany, as well as the Precarious Workers Pageant in Venice, Italy. Sholette is a graduate of the Whitney Independent Study Program in Critical Theory, Associate of the Art, Design and the Public Domain program at the Graduate School of Design Harvard University, as well as Associate Professor in the Queens College Art Department, City University of New York where he helped establish the new MFA Concentration Social Practice Queens (SPQ). https://www.tumblr.com/blog/gregsholette

Notes

[1] Boris Groys, On Art Activism, in e-flux n. 56, 6/2014: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/on-art-activism/. Note: All references are to this online essay.

[2] Recent books by, among others, John Roberts, Nato Thompson, Yates McKee, and Stevphen Shukaitis all seek to address the relationship between art and activism in both theoretical and historical terms.

[3] And of course the entangled “relationship” flows in both directions as witnessed by the Guggenheim Museum’s newly announced launch of its own social practice art initiative involving one of the artists who founded the project Conflict Kitchen that is discussed below: https://www.guggenheim.org/press-release/85742

[4] G.U.L.F. “On Direct Action: An Address to Cultural Workers,” efflux, 2015: http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/on-direct-action-an-address-to-cultural-workers/

[5] Cited in Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years the Dematerialization of the Art World from 1966 to 1972, University of California Press, p. 78.

[6] See Sholette “Disciplining the Avant-Garde,” 2005: http://critical-art.net/defense/Kurtz_Sholette.pdf

[7] Gilligan’s examples include Richard Prince’s endlessly recycled works, and Seth Price’s reworking videos that bear “a striking similarity to financial derivatives in one particularly suggestive way: they derive their value from the value of something else.” From Melanie Gilligan, “Derrivative Days,” in Sholette and Ressler, It’s The Political Economy, Stupid, pp 73-81.

[8] Stephen Wright, Toward a Lexicon of Usership, was published on the occasion of the Museum of Arte Útil at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2013. It is also available as a PDF online at: http://museumarteutil.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Toward-a-lexicon-of-usership.pdf

[9] http://www.multicians.org/thvv/borges-animals.html

[10] From Masha Gessen, Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot, Riverhead Books, NY, 2014. P. 2014.

[11] Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Closing Statement, August 8th, 2012, Khamovnichesky Courthouse, Moscow. See: http://www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2012/08/10/pussy_riot_trial_closing_statement_certainly_makes_one.html

[12] Dara Greenwald and Josh MacPhee, Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures, 1960s to Now, AK Press, 2010. Borrowing Greenwald and MacPhee’s terminology Catherine Flood and Gavin Grindon go so far as to propose in their excellent introduction to the Disobedient Objects exhibition catalog, “social movements are one of the primary engines producing our culture and politics, and this is no less true when it comes to art and design…While the organizations that produce disobedient objects might have little cultural visibility to begin with, social movements are instituent – they aim to institute new ways of living, new laws and new social organizations.” Disobedient Objects, V&A Publishing, 2014, pp. 9 &13.

[13] Lucy R. Lippard, “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s,” CAA Art Journal 40, nos. 1–2 (Fall–Winter 1980): 362–65.

[14] Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, Pluto Press, 2010, p. 121.

[15] In this essay I am setting aside more traditional Marxist and Communist party policies regarding art because so much of the movement culture generated in past decades from Reclaim the Streets to Occupy Wall Street is influenced by the anarchist Left.

[16] There are many engaging texts debating contemporary art’s autonomy or lack thereof, but perhaps most engaging are those that revolve around the Marxist concept of art’s subsumption to capitalist forms of production as in recent writings by Leigh Claire La Berge, Nicholas Brown, Kerstin Stakemeier, Kim Charnley, Marc James Léger, Dave Beech and John Roberts a taste of which is found in this 2015 online exchange: http://artanddebt.org/lets-talk-about-the-debt-do-for-responses/

[17] Alex Greenberger, “Art Without Permission’: Tania Bruguera and Dread Scott Discuss Art and Activism at the Brooklyn Museum, ArtNews, December 14, 2015: http://www.artnews.com/2015/12/14/art-without-permission-tania-bruguera-and-dread-scott-discuss-activism-at-the-brooklyn-museum/

[18] I take up some of this in the essay “Not Cool Enough to Catalog: Social Movement Culture and Its Phantom Archives,” http://www.gregorysholette.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/PEACEPRESS_FINAL_080511-copy.pdf

[19] Reprinted in Julie Ault’s Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material, Four Corner Books 2010, pp. 22-23.

[20] Lucy R. Lippard, “Visual Problematics,” originally published in The Village Voice 1982, edited and reprinted in the book Get The Message, E.P. Dutton, 1984, p. 282.

[21] Wodiczko & Sholette, “Liberate the Avant Garde?” in Marc Marc James Legér’s book The Idea of the Avant Garde: and What It Means Today, Manchester University Press, 2014.

[22] Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition, Verso, 2016, p. 242.

[23] See “The Grin of the Archive,” in Dark Matter, op. cit.

[24] Andrea Fraser, “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” Artforum. New York: Sep 2005. Vol. 44, Iss.1: http://occupymuseums.org/press/Andrea-Fraser_From-the-Critique-of-Institutions-to-an-Institution-of-Critique.pdf

[25] Hito Steyerl, efflux, 2016: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/a-tank-on-a-pedestal-museums-in-an-age-of-planetary-civil-war/

[26] “The painting was shown at the 1704 Salon and then…remained in the royal collections until after the Revolution, when in 1793 it was handed over to the Muséum Central des Arts de la République, later known as the Musée du Louvre.” http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/louis-xiv-1638-1715?selection=44896

[27] “Throughout history, living labor has, along with the surplus value extracted from it, carried on its own production—within fantasy…by virtue of its mode of production, fantasy constitutes an unconscious practical critique of alienation.” Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge, Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere, University of Minnesota Press, London, 1993, 32.

[28] Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, Pluto Press, 2010.

[29] Riffing off my concept of Dark Matter, Roberts describes this shadow art world’s modus operandi as a second art economy made up of individuals and groups who, for reasons of necessity or political persuasion, operate outside mainstream channels of artistic production and exchange including underemployed professionals, amateur artists, hobbyists and art students, aka “pre-failed” artists in John Roberts, Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde, Verso, 2015, pp. 23-26

[30] G.U.L.F. op cit. the concept of “de-occupying” space is explained by group members this way: “The de-occupy is intentional as, for a variety of reasons, we should consider our spaces as occupied — this land taken from its native people and occupied; our workplaces, taken by capital from the people, the workers, and occupied; we live under occupation; our struggle is to de-occupy. This knowledge emerged from the Occupy experience and its criticism by de-colonizing movements in NYC and workers movements in Delhi. Nitasha shared something relating to this as an example from the ground too.” (Cited from an email from Amin Husain and Nitasha Dhillon, 2/14/2016.

[31] For the most recent developments about these actions and the museum’s response see: http://gulflabor.org/ and full disclosure the author of this essay is himself a core member of Gulf Labor Coalition.

[32] Walter Benjamin, Thesis on the Philosophy of History, 1940.

[33] Ian Milliss, “Love Among the Ruins,”: http://milliss.com/love-among-the-ruins/

[34] Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), CreateSpace Publishing edition, 2015, p. 15.

[35] Nietzsche’s notion of active forgetting pivots on a tactical withdrawal of memory that as Gayatri Spivak describes in her unforgettable introduction to Derrida’s Of Grammatology “protects the human being from the blinding light of an absolute historical memory (that will, among other things, reveal that “truths” spring from “interpretations”), as well as an attribute boldly chosen by the philosopher in order to avoid falling into the trap of “historical knowledge.” Jacque Derrida, Of Grammatology, John Hopkins University Press, 1967, Spivak’s introduction p. xxxii.

[36] “Insofar as it breaks with the given assignation of tasks and aptitudes supposedly inscribed in our very own bodily frames, all emancipatory politics relies on a degree of fiction, namely, on the fictive gap between a given task the aptitude that alone is supposed to make a subject or group of subjects fit for it.” Bruno Bosteels, The Actuality of Communism, Verso Books, 2011, p. 264

[37] Unlike Alain Badiou’s concept of event, which rewrites history writ large, this proposed event-object is far more modest in scope, though it still offers a glimpse of change conceivable on a larger scale.

[38] “A comfortable, smooth, reasonable, democratic unfreedom prevails in advanced industrial civilization, a token of technical progress,” writes Herbert Marcuse in the introduction to One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society, Beacon Press, 1964. p.1.

[39] Even artists associated with the youthful Brooklyn “return to painting” movement can be slotted into this framework, see for example Rebekah Kirkman, “Paul Gagner paints anxiety and institutional critique in his solo show at Guest Spot,” City Paper, January 20, 2016: http://www.citypaper.com/arts/visualart/bcp-012016-art-paul-gagner-20160120-story.html

[40] G.U.L.F. op. cit.

[41] “The commons has become a crucial keyword in the language of critical theory, social movements, and activism in many parts of the world” writes Sandro Mezzadra, just one of many theorists adopting this term with varying degrees of political fuzziness today. This citation is from the preface to a new reader geared towards the emerging discipline of “communing studies” entitled Space, Power and The Commons: The Struggle for Alternative Futures, Kirwan, Dawney, Brigstoke editors, Routdlege Books, 2016.

[42] Of course this neo-Hegelian approach played directly into the needs of neo-liberal capital, see: Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” first published in The National Interest 1989, online at: http://www.wesjones.com/eoh.htm

[43] Elizabeth Landau, “Scan a brain, read a mind?,” CNN April 12, 2014: http://edition.cnn.com/2014/04/12/health/brain-mind-reading/ See also: Kelly Bulkely, “Data-Mining Our Dreams,” The New York Times, October 18, 2013.

[44] None of this of course alters the point Marx made more than a century and a half ago that all political transformations conjure up their own set of ghosts, though it does likely explain why Groys misread the specter of art activism as a “new phenomenon.”