Gábor Erlich

Six years have passed since the report of my colleagues on Hungary—the system named after its supreme leader Orbán is in its sixteenth year. The regime has consolidated into a full autocracy, whose cultural opposition is wrecked and sedimented. Orbán’s tireless efforts and maneuvering to build an illiberal international[1], have recently yielded significant successes, hence this update cannot solely focus on the conditions of the production of contemporary art[2], but it must zoom out in two steps to (a) offer a concise perspective on culture at large (or the never ending culture war) that is the buttress of such an illiberal system, as well as to (b) shed light on the pivotal role played by the culturalist cookbook in the global(izing) network of the alt-right.

Public monuments, private collections, and the >specter< of hegemony

In the field of contemporary art, we have witnessed an ever-encompassing grip of cultural capture—the main vehicle of terminating the dominance of the liberal elites.[3] Given that cultural production is predominantly state-funded, coupled with the centralized nature of governance in Hungary, the Orbán-regime has installed loyal directors on the top of key institutions.[4] Furthermore, the Hungarian Academy of Art (MMA)[5] as a ‘public body’[6] and its grip over the National Cultural Fund (NKA), the country’s main funding institution, has led to a perversely uneven redistribution of public money in the sector, grossly overcompensating the devout gang, their institutions, and the often zealous cultural agendas they pursue.

Despite all that, the symbolically (and internationally) still dominant liberal elites uphold a diverse scene of contemporary art, be it under a vastly altered framework. This dissident[7] scene operates, on the one hand, in some of the very few ‘freer’ pockets of the landscape such as municipal and district-funded museums/institutions and alternative/private/artist-run venues, as well as, perplexingly, in some of the for-profit commercial galleries.

Crucially though, the illiberal shock-therapy notwithstanding, the scene’s inner hierarchies, values, and political affiliations remained largely unchanged, which, we might argue, congeals the primacy of the studio-gallery nexus and that of the object, via the “spontaneous ideology of the art field.”[8] The local variant of it is notorious for immixing the two already contested notions of autonomy and independence. An artistic venture, this story goes, is independent if it refuses to (apply to and) accept public money, which, in turn, suggests that autonomous creation of art is possible in the realm of the commercial galleries[9] and the “duty free”[10] artworld. It is hence more than just a syntax hiccup: it allows for a facelift of the field, where the initial role of commercial galleries—the speculative commodification of artworks (on the backbone of invisibilized artistic labor)—is camouflaged by curated group shows of ‘progressive’ artists, often even by educational and research facilities. While the emergence of this broadened arena may seem to provide feasible opportunities, in reality, it merely ensures the survival and reproduction of the elites. The professional liberal scene becomes governed by, and dependent on, the selection model of capital accumulation which splits the field into a small but splendid band of winners and a large pool of increasingly precarious ‘losers.’ Whereas, from a Left perspective, the historic opportunity of the scene was to develop a thorough critique of and real alternative to both the bourgeois ancient and the post-fascist new regimes, to start thinking with interdependence[11] and autonomy-as-a-critique-of-autonomy[12], instead of racing towards total subsumption.[13]

Recuperated revolution, illiberal PMC, and the >base< of hegemony

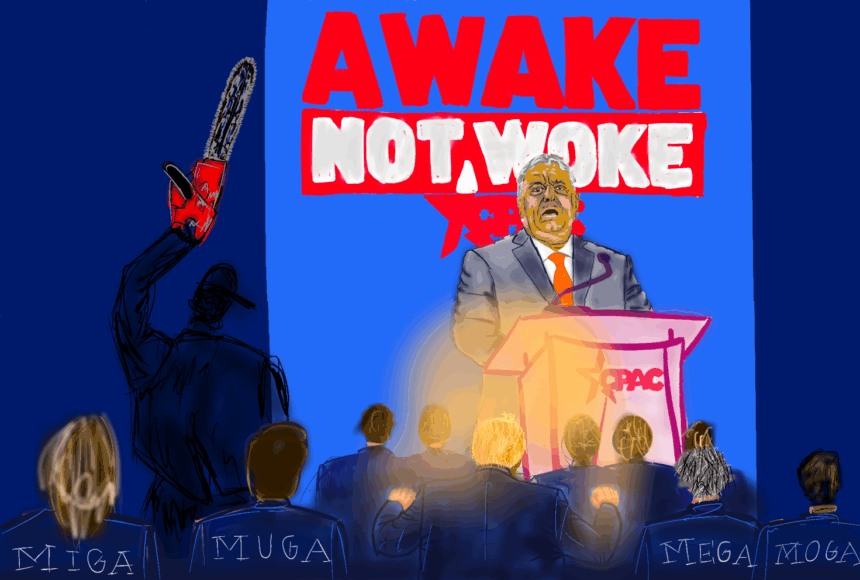

But, if we really want to understand the true nature of the regime, it would be absurd to accede to the universalizing bourgeois wont which takes professionalized contemporary art as the pinnacle of cultural production. For, substance of the system only reveals itself once we zoom out to the meso scale, to culture at large and its ‘war machine.’ Such militant jargon is not only Orbán’s personal allure, but it too meanders through a book by one of the key éminence grise of the system, Márton Békés.[14] The piece outlines the cultural strategy of the illiberal regime and designates the role of the alt-right intelligentsia in a society of perpetual warfare. Such methodology is best described by the phrase “perverse decolonization”[15]: Békés advocates for the hijacking and cooption of paramount ideas and praxis developed and mobilized by the radical Left from Gramsci to Malcolm X, to then use those in building a new—chauvinistic, racist, and misogynist—cultural hegemony. The capturing of the realm of art was only the first step in this ‘long march through the institutions,’ followed by far greater leaps (considering their societal significance), such as the semi-privatization of universities[16], the establishment of an institution tasked with training the new generation of elites[17], all the way to the PM’s defamation campaigns planting fear and hatred in the center of the collective political imaginary.[18] Orbán’s system does have a solid cultural agenda. With it, the regime stewards a large cluster that can be theorized as the illiberal professional-managerial class (iPMC), whose task is to use/implement this counterrevolutionary culturalist façade that covers for the accumulation process running incessant in the background (and often on fuels antagonistic to the total (post)fascist identity politics).

Global antiglobalists, sovereign sovereignty, and the >influencing machine<

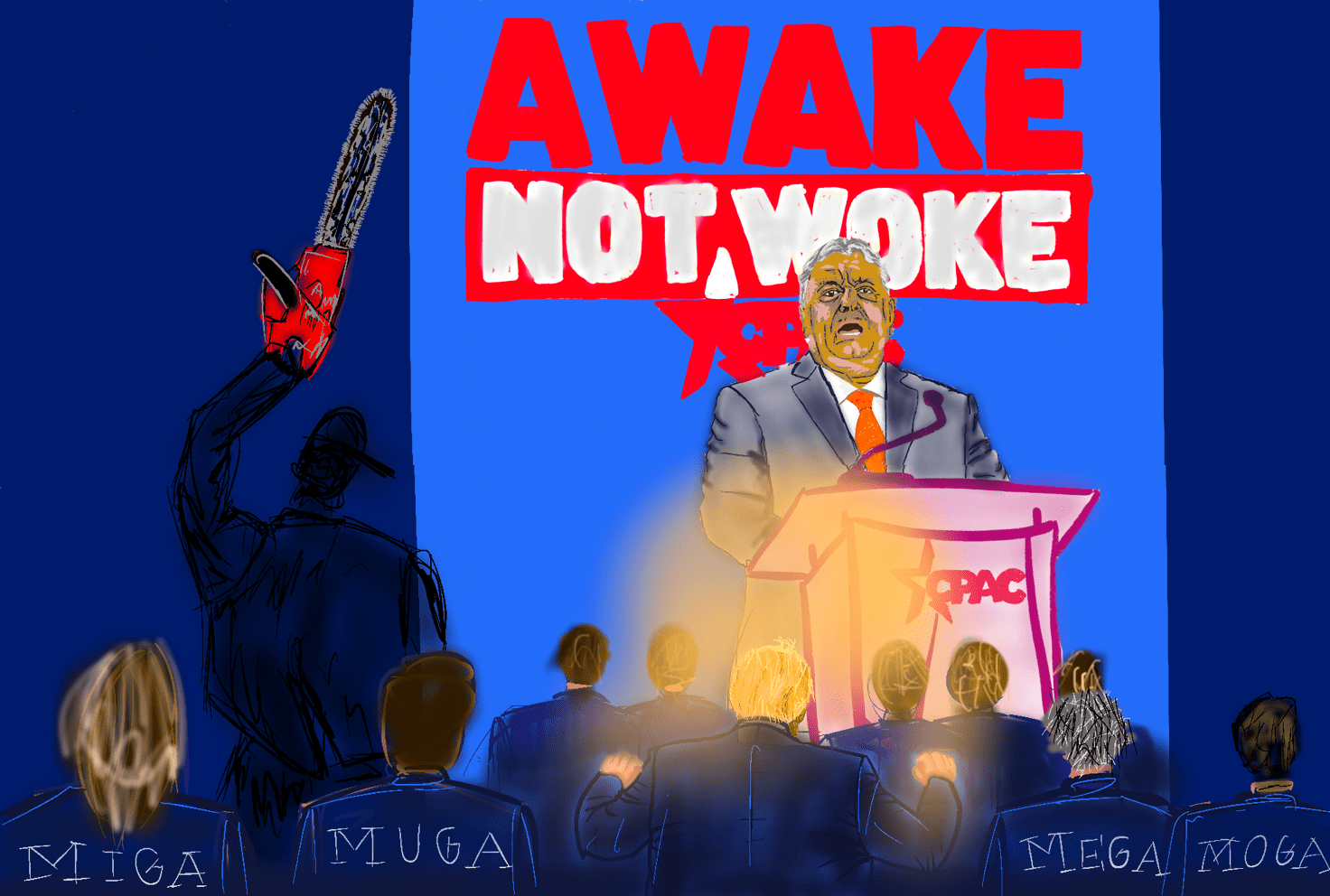

Another vestige back, the macro scale exposes that the (post)fascist alt-right, despite its isolationist rhetoric, has built a truly global network. Although the respective overlords fine-tune the credo to tailor bespoke domestic variants, (Békés’ text can be understood as a prototype for Project 2025)[19], the overarching culturalist agenda establishes a hodgepodge hegemony of post-truth, of unreason[20], nevertheless. The illiberal condition engineers a hatred-driven, exclusionary, and bigoted culture as veneer to harbor the tyrants’ only drive, capital accumulation through state capture or state sweep. Its main vehicle is the web of GONGOs[21] that manage the laundering of public opinion, the manufacturing of consent worldwide which hypernormalizes authoritarianisms and dictatorships from the USA to Türkiye, Argentina to Israel, Hungary[22] to Georgia, Rwanda to Russia via the eager labor of the iPMC.

Should we cheer that the liberal dominance has been enfeebled or finished by dint of the illiberal rampage? Ne’er! But we better get our act together: we must move beyond the old vested interests and hierarchies (no more artsy Draghi-reports!), and especially the elitism of the field, for this battle is not one to fight from the studio-gallery syndicate.

Gábor Erlich is an artist/activist/researcher from Hungary (MFA from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts – Intermedia), currently based in Tbilisi, Georgia. He’s a founding member of the art-advocacy collective Szabad Művészek-Free Artists which protests the Hungarian Academy of Art; member of the assembly ‘United for Contemporary Art’ that occupied the Ludwig Museum in Budapest. Erlich recently defended his PhD as an MSC fellow in art and political philosophy (under the aegis of the FEINART programme, supervised by John Roberts) in which he scrutinizes the issue of cultural hegemony in the East-Central European semiperipheries focusing on both the liberal and the illiberal eras of the region. Apart from writing, he is now working on an experimental documentary that seeks to contextualize the current uprising in Georgia in a way that challenges imperialisms and Westsplaining alike.

Notes

- The term, put forward by Fareed Zakaria, has been used in political science since the early 1990s. Orbán hijacked it in 2014 when he heralded the onset of a new period he calls illiberal democracy, at his regular annual programmatic speech delivered in Transylvania. It is a strong neologism, hitting right home by creating a total demarcation between the ‘us’ (illiberals) and the ‘them’ (liberals). Since the phrase has been covered and contextualised widely on the international stage, I will not go into more details. ↑

- The ‘Artistic Freedom Initiative’ put together a rather extensive report on the state of cultural institution and that of the institutionalised cultural capture in 2022, for more information, visit: https://artisticfreedominitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Artistic-Freedom-Monitor_Hungary_Systematic-Suppression.pdf ↑

- This dominance, or even hegemony, was forged in the period of ‘late-Socialism’, and was in place till 2010, which marks the onset of Orbán’s counter-offensive. Three Hungarian scholars have published major contributions to this issue, without the work of Ágnes Gagyi, Kristóf Nagy, and Márton Szarvas (amongst others, of course) it would be much harder to see the matrices of cultural dominance in Hungary and in the East-Central European semiperiphery. ↑

- Loyalty here refers to a personal rather than an ideological devotion, as there are largely different characters bestowed with key positions in the ‘System of National Cooperation’ as its founder likes to call Hungary’s autocratic ‘semiperipheral regime of capital accumulation’ (as the members of the Working Group for Public Sociology-Helyzet define the Orbán-regime). ↑

- Read more about MMA: their official website (https://www.mma.hu/web/en/index), a scholarly analysis by Kristóf Nagy (), anti-mma protest advocacy-action group (https://nemma.noblogs.org/2013/08/21/free-artists-who-they-are/)https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/handle/10831/104259), and the anti-MMA protest advocacy-action group (https://nemma.noblogs.org/2013/08/21/free-artists-who-they-are/) ↑

- Just as the Hungarian Academy of Sciences is tasked to oversee and guard the scientific output of the country, MMA was given the same rights and resources. ↑

- The word dissident takes us back to the 1980’s, and the art scenes of the ‘actually existing socialisms’, often referred to as ‘secondary publics.’ Not to equate the two historic periods, but there are clear resemblances between the two, especially in relation to the cultural elites’/intelligentsia’s position, practices, and social role. Certainly, this parallel universe structure can be understood as a natural self-defense mechanism of the scenes who wish to exist despite the ever-dire financial and intellectual circumstances, let alone the regime’s continuous attacks against them and their professions. Yet it is also reasonable to argue that using all resources and networks to maintain a quasi-independent scene leads to the societal isolation of that very scene, hence, a general image of an elitist bubble that has no real connection to the majority of the society can easily be forwarded by the ruling powers. ↑

- Oliver Marchart’s phrase from his 2019 book, Conflictual Aesthetics;Oliver Marchart, Conflictual Aesthetics: Artistic Activism and the Public Sphere (SternbergPress 2019). https://www.sternberg-press.com/product/conflictual-aesthetics/ ↑

- And also when financial support is provided by international NGOs, wealthy individuals, etc. ↑

- Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (Verso, 2019). ↑

- See for example: ‘I for Interdependence’ in Kuba Szreder’s 2021 book The ABC of the Projectariat;Kuba Szreder, The ABC of the Projectariat: Living and working in a precarious art world (Manchester University Press 2021). https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526161321/. ↑

- As put forward by John Roberts in his 2014 book Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde;John Roberts, Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde (Verso 2014). ↑

- Intriguingly, and as a proof that the regime does not rest on a thorough ideology, we shall mention that subsidiaries of the National Bank has built an art collection by acquiring works (chiefly) from the liberal elite’s most esteemed emerging and established artists via the mediation of collectors and key commercial galleries. ↑

- Marton Bekes is a scholar-turned-serviceman, whose 2020 book is titled Cultural Warfare – The Theory and Practice of Cultural Power. ↑

- As Degot, Riff, and Sowa argues in their book of the same title – https://www.archivebooks.org/perverse-decolonization-eg/ ↑

- Hungary’s state university network was disentangled overnight when the Orbán-government outsourced these crucial public assets to semi-private foundations who now, via boards of trustees (stuffed with loyal politicians and businessmen), run the universities, ending academic autonomy. ↑

- The most significant of these ventures is an institution called ‘Matthias Corvinus Collegium’ (MCC) which is a private advanced studies college that trains and financially supports talented individuals throughout the Carpathian Basin. The MCC was endowed by over a billion USD worth of real estate and bond portfolio, and is tasked to harbinger ‘new conservativism’ within and beyond the borders of the country. ↑

- The scapegoats are ever-changing to suit the current ‘struggle’ Orbán claims he’s forced to undertake, including but not limited to George Soros, the EU’s leadership a.k.a. ‘Brussels’, people fleeing war-thorn regions towards the EU, Ukrainians, local opposition, US democrats, liberal and Left intellectuals, NGOs, civil society organizations, the entire LGBTQIA++ community. ↑

- Note that Orbán’s ‘Danube Institute’ had a significant role in consulting the drafts of ‘Project 2025’. ↑

- I borrow the term from John Robert’s 2018 book, The Reasoning of Unreason – Universalism, Capitalism and Disenlightenment. ↑

- Government-organised non-governmental organizations, such as the aforementioned Danube Institute, or the Polish ‘Ordo Iuris’, but most infamously by now ‘The Heritage Foundation.’ ↑

- Orbán’s role is undoubtedly historic in these processes, he punches way beyond his league when becoming the poster child of the alt-right as much in the US as in, say, Georgia or Serbia or Bosnia-Herzegovina. ↑