On Teaching Palestinian Art History During a Genocide

Sascha Crasnow

When I was first approached in the wake of the events of October 7th of last year and the, still ongoing, violence carried out in Gaza, the West Bank, and now Lebanon and Syria, about writing something about Palestine, as an art historian whose work centers on contemporary Palestinian art, I wasn’t really sure what I, a white, Jewish, American could contribute to the conversation. It certainly did not feel like my voice was one that was most needed. And to be clear, I still don’t believe that mine is. However, I did start reflecting on what I always say when I’m introducing my class material to my students: What I aim to do as an art historian is not to speak for the artists and voices that I present to the class (or in my research for that matter). Rather, I seek to create a space where we can listen to the voices of those artists and discuss what it is that they are saying in their work. As the past year has shown, within the United States generally and certainly on college campuses in particular, there is a resistance to discussions about Palestine or the perspectives of Palestinians—often referred to as the “Palestinian exception.” The tensions around this became even more potent at the University of Michigan, where I taught for the last six years—a school with a sizeable Arab and Muslim student population[1] and an active SJP (Students for Justice in Palestine) chapter in SAFE (Students Allied for Freedom and Equity), yet also one that has appeared in national newspapers frequently over the course of the last year for the limitations [that campus authorities have imposed] on free speech on campus and even arrest of student protestors.

I, like many people I am sure, did my best to engage with activities that were happening on campus and follow the news from afar, but I often felt helpless and ineffectual. During the Fall 2023 semester I had multiple students who told me that friends and family members of theirs were killed in the violence, and many people feared for their loved ones. Students who had personal connections or some political investment in the region were sometimes faced with conflicted feelings about the events—feelings which sometimes changed as death toll in Gaza increased with each month and the narratives and images that appeared on social media and in some news outlets continued to reveal new horrors. Other students felt that they didn’t know enough about what was going on to participate in conversations around it. Some of these students were seeking out a place where they could learn more, especially about the voices and perspectives they weren’t seeing [represented] in much of the mainstream media. As the spring semester approached and I prepared to teach my Palestinian Art class again, I became aware that students may have been seeking out the class with more urgency than previous semesters, and may have wanted to look at Palestinian art as a way to understand the history and roots of the conflict. I found that creating a space for discussions around Palestine through art may in fact be a subversive way to have a safe space that does not require a “both sides” agenda or (spurious) presentation of scholarship and history as neutral. After all–no one suspects serious socio-political conversations to be going on in art history classes, right?[2]

I have taught my Palestinian Art class since starting my faculty position at the University of Michigan six years ago. The class is one that I had thought of, and wanted to teach, since early on in graduate school, as contemporary Palestinian art is my area of specialization and research. I also knew that it might be a hard sell to a department (see: “Palestinian exception”), but was fortunate to be given relatively free reign to design classes of my choosing when I landed in the Residential College (a learning community aimed at providing a small liberal arts college experience on the large University of Michigan campus).[3] The first time I taught the course, I believe it only had seven students in it—the minimum enrollment necessary to run. But those seven students were invested in the material and the opportunity to learn about Palestinian art history and hear a Palestinian perspective through art. They told their friends. The next year the class had nine students… then twelve. Word of mouth continued to grow the class. It became known among certain students as an alternative to the other courses on campus that taught the “Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” which many students found frustrating in their attempts at “neutrality” and, in at least one class, the requirement that students write a paper from the opposite perspective from the one with which they agreed (the idea of asking, for example, a Palestinian student whose family was exiled and who perhaps had family members killed during the Nakba to write in defense of the Israeli government is unconscionable to me). As registration opened for Spring 2024 classes, I checked the enrollment. My Palestinian Art class, which had typically been the smallest of my three classes in spring term, was the first to fill. Students were looking for courses that talked about Palestine, and they were finding one in Art History.

Over winter break I chatted with other faculty and friends, exchanging ideas about how I could and should adjust the class to account for the fact that we were discussing a history that was connected to contemporary events, and that artists were engaging with the history-in-the-making we were witnessing. Ultimately, I came up with three main changes to my syllabus. The first was to acknowledge and discuss notable developments happening in Gaza and throughout Palestine in the class as they happened. This gave space for students to inform other students about things that they had learned, ask questions, and understand the continuing history of Palestine, as we studied the art production coming out of it. This also included discussions of the protest organizing, administrative responses, and other occurrences on the University of Michigan campus. Students were given space to react and share their thoughts about the way that organizers were engaging in protest and the university was responding. When Palestinian photographer Motaz Azaiza came to give a talk, I secured tickets for the class and we attended what many of us agreed was an uncomfortable event. In a discussion that took place at our next class meeting after the talk, I asked the students to share their impressions of the event, how it made them feel, and what it had made them think about afterwards. Students expressed discomforting feelings of voyeurism as audience members sitting before a man clearly hurting and in trauma. Students questioned how and whether their activism on campus was actually impacting the lives of those in Gaza, or whether many of their actions were merely performative.

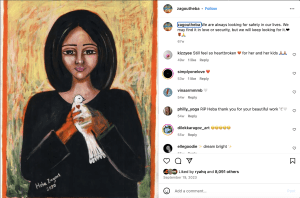

The second change I made was to end each class with a couple of examples of works by artists, designers, and other cultural workers that were made since October 7th 2023. Sticking with the theme or main focus for the day, we would end each class by drawing connections between Palestinian artists from throughout history and the works artists are making today. This served to show the relevance of earlier historical moments and visual culture to the contemporary moment broadly, but also in the specific context of Palestine—how many of the same concerns still exist, how much of the same iconography is still used, how artists are repurposing motifs in their new context. For example, around the middle of the semester we had a unit specifically looking at Palestinian women artists. We discussed artists like Zulfa al-Sa’adi (1905-1988), Juliana Seraphim (1934-2005), and Mona Hatoum (b. 1952). At the end of the class, we spent some time looking at the work of Gazan artist Heba Zagout (1984-2023), who was killed by an Israeli airstrike on October 13th 2023. Zagout’s style references much of the iconography that students had already seen in the post-Nakba artists earlier in the semester, including Palestinian villages, Jerusalem, tatreez (embroidery), olive trees, the keffiyeh, and house keys. At the same time, like Seraphim and Hatoum, she highlights the experiences of women in particular. By introducing my students to Zagout’s work, they come to see how some of the same nationalist imagery used in the post-Nakba period is still utilized by contemporary artists to express their love for Palestine and their desire for nationhood. Additionally, they are able to understand the direct effect of the violence going on in Gaza on both Palestinian art production and on the lives of some of the most vulnerable people—Zagout, a mother of four, was killed alongside two of her children.

The last change I made to the course was to include a final unit that looked specifically at Palestinian art made since October 7th 2023. Unlike the works that I had introduced throughout the semester, which I had brought in to demonstrate their connectedness to previously existing themes in Palestinian art history, for this final unit, I asked students to go out and do their own research, looking at social media, the Palestinian Poster Project Archives[4] (which we had looked at earlier in the semester), and other places where they had encountered visual culture engaging with the war in Gaza. This is something I typically do a few times during the semester—give students agency over the works discussed in class by having them bring in their own examples. This allowed them to tap into themes, iconography, and artists that they had found interesting throughout the semester, and to see how they were engaged in responding to and articulating the realities of the contemporary moment. Students brought in not only works by Palestinian artists but also those by artists creating work in solidarity with them—noting how previously insider visual references like the watermelon had become global referents for Palestine. Looking at works of art referencing a historical moment as it was happening made clear the relationship between art and history in art history as a field, and how visual media, including but not limited to the fine arts, can make visible and legible a variety of perspectives in response to a historical moment. In my own experience, it has been fascinating to witness the symbol of the watermelon, for example, one that as someone deeply immersed in Palestinian art and visual culture, I have long recognized as a symbol of Palestine/the Palestinian flag, become globally recognized as such. I have been particularly struck by the way that online activists have utilized it as a way to bypass censorship on social media associated with using the word Palestine or Palestinian, by replacing it with the watermelon emoji.[5] As many students had encountered this in their own social media use, this was an accessible entry point for discussions of the history of that and other symbols that make up Palestinian nationalist iconography.

I don’t pretend that my teaching Palestinian Art is the most crucial and impactful gesture that one can make in the midst of a genocide. However, at a time when it is easy to feel helpless to do anything, I returned to my teaching as a means to feel I was doing something. The response from my students validated this feeling. There were those who were seeking out a space to explore the visual culture of a people and movement they were protesting on behalf of on campus. There were those who didn’t feel they knew enough about the history and contemporary realities in Palestine and felt the obligation to learn more. There were those who were seeking a space where the art history they loved could reveal its relevance beyond the confines of museum spaces and elite galleries. I was grateful to be able to create a space for all these students and to introduce them to a number of voices to which they had previously not had access. At a time in the United States where the value of art history and the humanities broadly is constantly questioned and belittled,[6] art reminds us of the human voices involved in the headlines that are reduced to statistics and politicking. Art and the humanities have something to tell us about the world that we live in and the global socio-politics that shape the lived realities of its inhabitants. It was a reminder, to me at least, of why art history matters, why the humanities matter, and why a liberal arts education that allows for academic freedom matters.

Since last spring semester, tensions on the University of Michigan campus have continued to flare. Students have been arrested and charged in relation to protests. Administrative policies on a number of campuses across the country have championed a “diversity of voices” while also silencing and restricting the expressions of pro-Palestinian voices. The Palestinian exception has, it seems, only become more potent on and off college campuses. This spring, I will be teaching my Palestinian Art class again, though this time at a different campus, one with a very different demographic than the University of Michigan and one that is much less politically engaged. And yet from what I’ve seen already in the classes I’ve taught so far, students here too are seeking out the voices of those that feel they are not hearing. As we have now surpassed a year of the war on Gaza, and an expansion of devastation into the West Bank and surrounding nations, the need to foster space for these voices in my classes becomes ever more crucial.

Sascha Crasnow received her Ph.D. in Art History, Theory, and Criticism from the University of California San Diego in 2018 with a specialization in contemporary art from South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA), especially Palestine. She writes on global contemporary art practices, with a particular focus on SWANA (South West Asia and North Africa), race, socio-politics, gender, and sexuality. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Art Journal, the Journal of Visual Culture and Lateral, as well as in a number of edited volumes. Her book project, The Age of Disillusionment: Palestinian Art After the Intifadas, is under review with Duke University Press. She is also co-editor of the Queer Contemporary Art of Southwest Asia and North Africa with Anne Marie Butler, which was published by Intellect Press in October 2024.

Notes

1. The large presence of Arab and Muslim students on the University of Michigan’s campus is in large part due its proximity to Dearborn, which along with some other areas in the metro Detroit area, is known for being the first city with an Arab-majority in the United States (55% as of 2023), the result of multiple waves of immigration from throughout the Arab world starting in the late nineteenth century.

2. I am pretty sure many art historians expect this, but sometimes I think it is our little secret. ↑

3. There are also multiple instances of faculty who have lost their positions over taking on the issue of Palestine. See for example, Steve Salaita (https://ccrjustice.org/files/Salaita_Factsheet_1-29-15_0.pdf) and Maura Finkelstein (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/academic-freedom/2024/09/27/tenured-jewish-prof-says-shes-fired-pro-palestine) to name the most widely publicized and most recent examples. ↑

4. https://www.palestineposterproject.org/ ↑

5. I discussed more about the history and contemporary usage of the watermelon in December of 2023 with the New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/style/watermelon-emoji-palestine.html ↑

6. I still haven’t forgiven President Obama for his quip about the value of an art history degree, though this comment was indicative of a larger trend that continues today that sees STEM majors as more valuable than humanities majors, something impacting the shape of American higher education. ↑