Socially Engaged Art in India: Three Case Studies (Part 2)

Sreejata Roy

Introduction

In contrast to the case studies published in the previous issue, which discuss art projects in public spaces and considers the beginning of Engaged Art in India, this essay delineates specific participatory initiatives that began as focused individual efforts and developed over time into an organization, a trust and a collective, respectively.

This section of the essay uses three case studies of ongoing Socially Engaged Art projects in diverse locations in India to illustrate the development of SEA in India between 1990 and 2021. All three projects – one rural- and two urban-based – were founded by women artists in an effort to claim/reclaim public spaces, usually not hospitable/often openly hostile and precarious for women, as sites for creative engagement. The three artists use feminist perspectives as they engage, interpret and materially transform the site, permanently or briefly, partially or wholly. Such transformation is quite radical, for traditional Indian culture is so heavily infused with patriarchal privilege and overt/subtle misogyny that women in general, particularly underprivileged women, are rarely supported when they choose to assert autonomy or agency in male-dominated public spaces. DIAA (Dialogue Interactive Artists Association), founded in 1997 by Mumbai-based artist Navjot Altaf, is located in the tribal region of Bastar in the state of Chhattisgarh in Central India. Through this organization Altaf has initiated collaborations between tribal artists and visiting international artists through workshops at the Shilpi Gram studio in Bastar.[1]

Contextual Background

All social entities necessarily produce their own space, as a manifestation of their actual/perceived realities, fixed/fluctuating self-concepts, and ways of doing/being. Socially produced space is not a mere aggregate of people and objects. Rather, it is a mode of production – it continuously generates and transforms relationships, meanings, discourses and ideologies; it is both repository and instrument of externalized thought and action; it is a semiotic cache, a diffracted field of signs and symbols. Conceptual, social and cultural space, whether produced by the entitled or the disenfranchised, ultimately acquires a political character since groups can directly or indirectly use the space to inscribe and replicate forms of social dominance, or to resist them.

Most private and public spaces in India are hierarchically ordered through various exclusion and inclusions, and the experience of public space is quite different for women and for men. The geographical and architectural elements of public space are arranged to restrict and control women’s access. Socially constructed “gendered space” impacts and inscribes social relationships, and reinforces the normative overt manifestation of male socio-economic power and privilege.

Critical scrutiny of the broad concepts of “public” and “private” affirms that Indian social spaces are rigorously gendered, with women’s place in the house, and men’s place in the world outside it.[2] Across class, all women are expected to submit to patriarchal custom, subject themselves directly/indirectly to direct/indirect forms of male control and custodianship, and unquestioningly participate in scripting a family narrative within the security of the home. Women who through choice or circumstance or exigency shape their own destinies outside this framework are seen and judged as a “problem”, and risk being penalized, stigmatized and/or ostracized by family, community, and society at large. Within this seemingly intractable ethos of gender discrimination, underprivileged women are disproportionately affected, enduring economic hardship as well as physical and sexual harassment, abuse and violence.

More generally, scholars like Massey have pointed to the overwhelming “multiplicity” that characterizes the social spaces of urban India, and their ongoing transformation under larger socio-economic pressures as the nation grinds through the politically imposed, ecologically violent, tortuous edict of further “development” that will apparently one day nudge India out of the “third world”.[3] Urban public spaces have organically expanded and diversified through migrant presence. Major cities in India, as elsewhere in the global South, face the constant influx of millions of impoverished rural and small-town migrants seeking employment and opportunities for a better life. Everywhere, most poor migrants live in large illegal or quasi-legal slums that are complex, highly gendered, multilayered spaces with people of different classes, castes, ethnicities and religions packed together in squalid conditions.[4] These sprawling, struggling settlements are always in flux, and always under threat of eviction/demolition by municipal authorities who view migrants as trespassers whose marginalized spaces are to be arbitrarily controlled under the rubric of public health, civic order, or of the ongoing “development” and “beautification” of Delhi as a “global” city.

Contextualizing the emergence of new art practices in India in the 1990s, Geeta Kapur argues that the “recognizing of the new forms of marginalization, promoted by the hegemonic combination of the national and the global has sharpened the language of art.”[5] This section will demonstrate how the three Socially Engaged Art projects discussed here have attempted to inscribe women’s experiences of public space and transform the gendered usage of public space in contemporary India, and in the process created new modes of women’s empowerment as well as new iconographies and a new symbolic grammar.

1. DIAA (Dialogue Interactive Artists Association) in Bastar district, Chhattisgarh, Central India (2000 – present)

The Bastar region is the traditional home of the Adivasis, an ancient aboriginal/indigenous/tribal community that has inhabited the region for millennia. The local economy is dominated by agriculture; for a long time the area had been known as India’s “rice bowl” as Grant Kester has mentioned while he was there on site.[6] This has since changed, as the tribal population is under constantly renewed threat of forced displacement with their cultivable land now being appropriated by the state and large corporations wanting to mine the rich lodes of minerals in Bastar. This is opposed by local communities, and their social spaces have become nodes of mobilization against larger forces. The Adivasis have a history of collective resistance, from the colonial era into the post-Independence period (after 1947). The latter was marked by Adivasi struggles against caste discrimination as well as against policies of economic and national “development”. The conflict has intensified from the 1990s onwards, within the profiteering ethos of neo-liberalization and globalization.[7] In 2020, Altaf noted that the communities involved in her Bastar projects were therefore generally perceptive with regard to the politics of dissent, and the use of social spaces to re-inscribe and reinforce strategies of dissent, including through the medium of art.

Having stepped out of privileged dominant urban culture in order to engage for the long term with a disenfranchised minority in a “backward” rural region, for all aspects of her Bastar work Altaf relies on the trust she has earned through her deep and multi-faceted relationship with a particularly vulnerable minority population that mainstream prejudice continues to delineate, neglect and abject as “backward” and “uncivilized”.

Nalpar (2001)

In the late 1990s, DIAA negotiated a strategy with neighborhood communities to explore a collaboration with village women as an experimental model for the Nalpar project. Altaf’s first intervention was in 2001 at a site in the Bandapara neighborhood of Kondagaon village in Bastar. It took the form of a nalpar, a circular wall erected in the space around the public hand-pump, a main source of household water for the community (Figure 1). Since women and children primarily do the arduous daily chore of fetching water, the intervention took the form of a wall specially designed to create a private enclosure for women congregating at the hand-pumps. The intention was to create a protective, democratic space for women within a hierarchical and patriarchal ethos wherein the mandated division of labor enables men to continually and closely watch, monitor and control the movements of the women in their families as Kester observed when he visited Bastar.[8]

The structure was conceptualized by three local artists (DIAA members Rajkumar Korram, Shantibai, and Gessuram Viswakarma) in collaboration with village women who, through workshops with Altaf, developed a unique aesthetic of signs and symbols intrinsic to tribal spiritual life; these were incorporated into Nalpar’s design and decoration. Thus collaboratively rendered, and authentically reflecting the tribal imaginary, the new structure served two vital functions. First, it had a platform at a convenient height so that women could place their full vessels and buckets there before lifting these onto their heads. In doing so, this design offset the strenuous upward action that led to back strain and muscular-skeletal problems that women developed through the customary practice of lifting heavy vessels directly onto the head from the ground. Second, the structure ensured privacy, providing women with an experience of collective socialization and group solidarity in a manner that “occluded from the sovereign male gaze”.[9] The first Nalpar was followed by three similar structures in Kondagaon (2004-2005) and four in the neighboring villages of Sambalpur (2005) and Kondgoannaka (2013).

Pilla Gudi (2000)

DIAA’s second intervention in Bastar was Pilla Gudi (“Temples for Children”), which took the form of alternative spaces where Adivasi children and youth could gather to play and learn outside the traditional schooling framework (Figure 2). Travelling to balwadis (local schools) and public meeting places such as temples and village community center’s, the artist group (Rajkumar Korram, Shantibai and Gessuram Viswakarma) had extended conversations with villagers about mainstream education strategies in the tribal areas. While advocates for these instructional approaches present them as an instrument of wider social “progress”, they are also experienced by locals as form of cultural indoctrination and forced assimilation that suppress and erase indigenous knowledge. Through dialogue with young people from tribal and Dalit communities, the artists realized that the next generation were becoming more and more ignorant of their culture and history. Hence the need and the significance of building a space of alternative pedagogies, where the young people could be exposed to the politics of knowledge, cultural differences, indigenous practices and mythology, as well as to the realities of marginalization, social struggles, and tactical survival in what is viewed, neglected, and dismissed by the mainstream as a “backward” part of India inhabited by “backward” populations.

Artist Rajkumar designed the first Pilla Gudi in Kusuma village, 150 kilometers outside Kondagaon, repurposing a temple of the Mother Goddess “Matanar”, a venerated tribal deity, into a space for learning. The temple ceiling was carved with deities gazing downwards at the worshippers below. Rajkumar replaced these sculptures with an overhead mirror, so that when people looked upwards they would see themselves – i.e., the real, rather than the mythological. DIAA used these spaces to develop workshops with local children. Altaf designed the second Pilla Gudi at Shilpi Gram, an open-air studio-cum-amphitheater established by the famous Adivasi artist Jaidev Baghel. It functions as a meeting and performance space, comprised of a tiered circular seating arrangement that surrounds a stage with a floor of sand. Altaf, Shantibai, and Raj Kumar collaboratively designed the third Pilla Gudi, working with children from Kopaweda village. That space transformed into a meeting place/playground as suggested by the children.[10]

The site, a cardinal variable within Socially Engaged Art, has been defined as “not simply a geographical or an architectural setting, but a network of social relations, a community”, with the artist and his/her sponsors envisioning the artwork “as an integral extension of the community rather than an intrusive contribution from elsewhere”.[11] Discussing in 2020 how DIAA practices reframe site-specificity, Altaf reiterated that her work in Bastar with the artist Rajkumar Korram, Shantibai, and Gessuram Viswakarma was “context-sensitive”, inclusive of the participation of people from specific areas, and remains focused on processes of human interaction and social discourse. Altaf also states that community-based site-specific practice involves a methodology quite distinct from practice within a studio. Altaf’s work falls under the category of “community-based site-specificity”, wherein sites themselves are generative, with creative work materializing extemporaneously from the site itself, and materially integrated with it, freighting it with signifiers, implication and resonance.[12] The site of production of the artwork cannot be separated from the site of its reception, and the experience of production is elided with the experience of reception.

In the Bastar projects, the action of art-making is undertaken as a collaboration between the local community and the four DIAA artists (Altaf, Korram, Shantibai, and Viswakarma) through a process which involves discussion on strategies among the artists themselves and, simultaneously, dialogue with the community. In order to understand the area’s social networks, dialogue extends from the immediate neighborhood and community to adjoining villages. The artists document community articulations around fundamental issues regarding human dignity and respect for Adivasi culture. The artists consider it crucial to learn from the lived knowledge and experience of local communities. They also inquire into how to challenge / bridge the gap between learner and teacher, and how both make efforts to be equally vulnerable and open in the knowledge relationship. In the context of Nalpar, there was a meshing of the two modes of collaboration: the artist group interacting with the local people in order to study the nuances of the indigenous social space and Altaf engaging specifically with local women in order to learn about Adivasi symbols and other aspects of their traditional knowledge that could be assimilated into project aesthetics.

For Altaf, the most striking part of a genuinely collaborative process is that as participants go deeper into the project, insights emerge that may be unexpected, dissonant, disruptive and in fact may transform, subvert, or reverse the group’s previous ideas and decisions. Authentic collaboration thus mandates flexibility, even while dialogic practice also needs a “discursive framework” that organizes the participants sharing understandings, reactions, decisions, and thoughts[13] The Nalpar sites are radical interventions in that they were collaboratively created; for the first time, in that particular context, local women had a unique, secure, desired social space to inhabit amidst their arduous daily routine.

The aesthetics of Altaf’s Bastar projects have emerged entirely from the her collaborative practice and are intimately linked with the politics of inclusion. Collaborative practice has made her more keenly aware of how art systems can so easily function as forms of a power structure built on particular aesthetic values and judgements, As mentioned earlier, the Nalpar structures were decorated with the prehistoric signifiers of water and earthen pots, which are still used by Adivasis in their traditional patterns, in contrast to the modern signifiers for water taps and handpumps that are today also used as election symbols by political parties. It took many days of working together with the community to visualize the design of the wall. The aesthetic evolved through ongoing dialogue with the participants and derives from their traditions and cultural experience. The aesthetic reflects a conscious agreement among the artists and the community to reject the idea of any aesthetic hierarchy and aesthetic judgement, and to advocate for remaining open to experimentation. This creative ideology invokes a system of equal aesthetic rights for artworks, artists and craftspeople, whatever the context, circumstance, and level of enfranchisement. Altaf’s objective was not to look at Adivasi art merely in terms of form and symbolic idiom but to understand it in relation to the historical and cultural context within which the indigenous works are produced, and also to examine the self–“Other” or insider-outsider dynamic. She intended to engage with the visual field from a premise informed by progressive politics, just as she had observed and studied contemporary art practices in other locations.

Altaf is also interested in studying the processes of creating and securing cultural spaces such that provide opportunities for critical reflection and for the application of critical thinking. In the Bastar projects, she initially had a purely creative role, visualizing the artworks and initiating the communication/collaboration with local artists and the local community. Later she enabled the expansion of art practices through people’s participation in creative dialogue, and by inviting artists from outside the region, as well as international artists, to work with local communities. Her role has now transformed into that of a facilitator, and includes negotiating the socio-cultural differences and aesthetic frictions that can manifest in discussions and on the ground between urban and Adivasi artists, between the artists and the Adivasi community, and between Indian and international artists. She feels very strongly that the marginalized and underprivileged artists and communities whose contributions are integral to public art projects and Socially Engaged Art initiatives should not be treated as raw material, i.e., commodities to be used by artists, curators, arts organizers, the cultural establishment, etc. Yet repeatedly we see such communities being objectified, muted, excluded, manipulated, and denied their due place within the realm of these socially-oriented and apparently democratic genres.

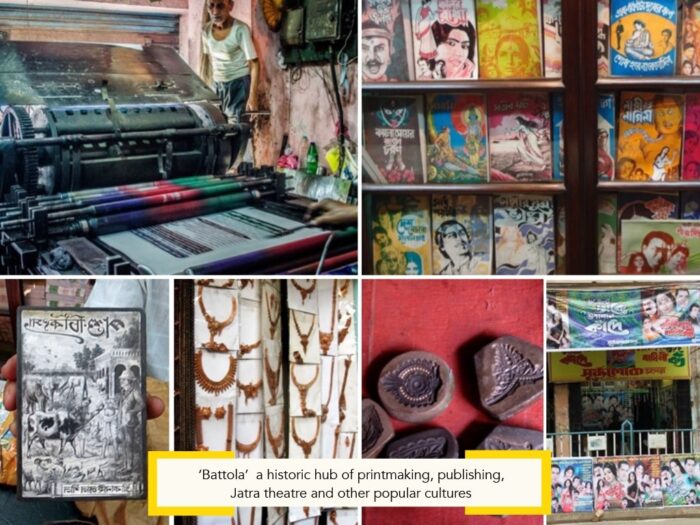

2. Project: Hamdasti Collective in Chitpur road, Kolkata, West Bengal (2014 – present)

Hamdasti was founded by art practitioner Sumana Chakraborty in 2013. Returning to India with a small grant after completing her master’s degree in art and design at Harvard University, she used the money to initiate the collective’s first interventions in the locality of Chitpur (Figure 3). Situated in Old Kolkata, Chitpur is a microcosm of the city, a place where many different communities coexist in diverse kinds of relationships. The turbid Hooghly river runs along one side of Chitpur, an early printing hub that was also once famous as a haunt of travelling folk theater, jatra (Bengali folk theatre) companies. It is a dense and cluttered space, with derelict buildings, artisan workshops, a bustling wholesale market, pavement vendors, and decaying old mansions with courtyards still used for performances and rehearsals. Chitpur is a generally conservative area and women are not very visible in its public spaces. It is now home to a diverse migrant demographic, but the native Bengali middle-class families, who have lived there for generations and shaped the local culture, still dominate the neighborhood ethos.

Hamdasti’s focus is on community-based art, and it provides fellowships to city artists for long-term engagement with communities, focusing on points of friction or conflicts of opinion between clearly defined social groups. Chakraborty clarifies that the site-specific art interventions were structured not just to accommodate the formal aspects of the built environment “but also to find that edge to play with”.[14] This is also the fulcrum of her individual practice that she continues in parallel with the Hamdasti work: “I always try to find a point of discomfort, take it forward till I hit a nerve ending. As soon as I find myself becoming comfortable, I look for another point of discomfort, provoke myself with another edge so that I can keep pushing the inquiry to its furthest extent.”[15]

The project Chitpur Local (2014-2017) took the shape of two public art festivals: Chitpur Local I and Chitpur Local II. In both phases the area became a place for participatory creative experiments, beginning with local school students and reaching out to neighborhood residents, shopkeepers and craftspeople, who were initially reluctant to participate but became curious and responsive after noticing the students’ keen involvement. The festivals were well attended, helped to deepen and strengthen community networks, and brought Chitpur to the notice of the city’s art establishments and cultural organizations. The project enabled both the artists and local people to recalibrate their established relationships to the neighborhood, once a creative hub, but over time had lost its vibrant energy. The project also allowed residents to engage with outsiders (artists) and experience something fresh, different from mundane daily life, within their habitual spaces.

Chitpur Local I (2014-2016)

Preparatory work for Chitpur Local I began six months before the event. Chakraborty and a group of three artists (Nilanjan Das, Manas Acharya, and Avijna Bhattacharya) held after-hours creative workshops with students aged ten to fourteen in Oriental Seminary, a local heritage school for boys (Figure 4). The school’s teachers were Hamdasti’s first collaborators during the four workshops held each month. Workshop participants established new relationships with their environment (Figure 5), recuperating meta-histories of the neighborhood spaces through conversations with residents, gradually learning about the craft traditions of the locality, connecting with people at shops, libraries, photography studios, and courtyards while documenting diverse paths from their home to the school. Mentored by the four artists, workshop participants mapped the locality in terms of residents’ stories, spatial positions, points of tension, points of encounter, points of misconnection, and much more. There was a changing flow of mentors and participants, but this mapping project has continued into the present.

The four artists also began going into the locality themselves, interviewing people and generally talking with residents, which helped to draw the larger community into festival’s ambit. Initially, the artists and the community engaged with the art interventions through different entry points, which created some discomfort, but along the way they were able to develop a mutual understanding. One example is the case of local art teacher Chayanika Dey who lived with her family in the lane adjacent to Diamond Library, a century-old bookshop. Dey ran a private art class at her home, and the artists began a joint mapping project with the art-class pupils and the school students, creating a bridge across the social differences between the two groups. This generated a new social synergy amongst the youngsters, each group providing the other with a new perspective on the experience of their familiar neighborhood.

For Chitpur Local I, Hamdasti was meticulous in keeping the spaces of intervention relatively closed in order to avoid the exoticization that can quickly happen when underprivileged and marginalized communities participate in public cultural practice, and in order that the works should primarily reflect local realities delineated by local participants. But in order to receive objective feedback, the collective did invite a few outsiders to the festival to view the works.

Chitpur Local II (2017-2018)

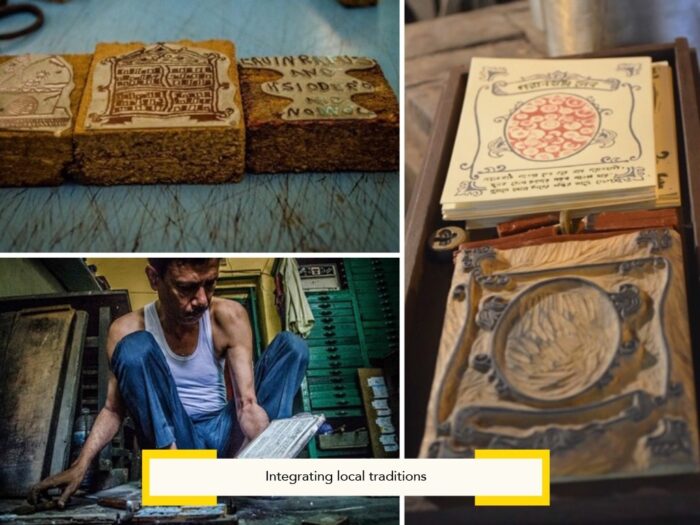

For the next edition of the festival the collective put out an open call for city cultural practitioners to collaborate with Hamdasti in conceptualizing and rendering new interventions in Chitpur. The selected group – Suhasini Kejriwal (visual artist), Dipaman Kar (sculptor), Ruchira Das (curator), Srota Dutta (writer), Anuradha Pathak (printmaker/installation artist), Varshita Khaitan (graphic designer), and Nilanjan Das (printmaker) – brought their own ideas of art and social practice to the collaboration, and accepted the challenge of switching disciplines, working outside their area of expertise and in a different medium or context. For instance, a visual artist worked with rubber-stamp makers; a curator worked with schools on their art education curriculum; a sculptor worked with local clubs; an art critic worked with old photography studios; graphic designers, installation artists, and printmakers all involved themselves as educators, combining traditional technologies with multifaceted demonstrations of contemporary arts. The collaborative work was often undertaken in the different dalans (courtyards) of Chitpur’s old mansions, in earlier times used for rehearsals, musical concerts, theater performances, and other cultural events. The present occupants of these houses were interested in the collective’s documentation of the dalans, and amenable to their courtyards being used for cultural activities. Hence through the festival these private spaces were temporarily converted into community spaces (Figure 6).

The project’s art interventions in Chitpur added something significant to the local environment by excavating the area’s meta-histories, based on Kolkata’s larger social narrative that is strongly associated with classical arts practices as well as subaltern popular cultures. Practitioners within the area’s hybrid earlier arts realm included the virtuoso printmakers of Battala, performers of jatra (Bengali folk theatre), kabials (street poets/singers), nautch (dancing) girls, courtesans, prostitutes and actresses, and patrons and connoisseurs included the modish-yet-traditional babu and bibi (nineteenth-century male and female Bengali elites). This social idiom eventually dissolved into the graphic arts of woodcuts and engravings and was subsequently replaced by cheap lithographs and oleographic prints that flooded into the markets of Calcutta in the first half of the twentieth century.[16] Hamdasti enabled the city’s artists as well as local people to re-establish relationships to this neighborhood, once so culturally active and dynamic, but depleted over time. The project also allowed residents to engage with outsiders (artists) and experience something fresh, different from mundane daily life, within their habitual spaces.

Hamdasti’s efforts culminated in Peers of Chitpur (2015), a two-day festival spread over twelve venues in the locality, attended by about 800 people from all over the city. Events included heritage walks, film screenings, discussions, talks, and small exhibitions. “Organising all this was a kind of madness in logistical terms, but it was also very stimulating and rewarding,” commented Chakraborty.[17] She explained that the festival was structured “so that so that audiences could not be passive spectators, they had to engage one another, have conversations”, and that the “ecosystem” of neighborhood collaborators worked efficiently.[18] Students did all the legwork, teachers and parents worked as volunteers, and residents served as festival guides, taking visitors through Chitpur’s streets and by-lanes.

Hamdasti’s intent has expanded from an initial drive to revitalize and conserve the heritage of Chitpur. “Local people have understood that our intervention is not about conservation, but about articulating local realities. Heritage is an elite concept, but very often residents on the fringes of or within heritage areas actually live in poor conditions,” says Chakraborty.[19] The project is now directed towards the facilitating of encounters which, ideally, would take local people outside their zones of familiarity and push the boundaries of their imaginations, nudging them towards a shift in self-perception and perception of the community.

The two phases of Chitpur Local embedded creative collaborators on the ground; new community networks offered distinctive contributions to the festival’s structure, initiating dialogue and activities in the different private and public spaces. The early participants later returned in the role of guides and mentors, while the artists became more deeply immersed in sharing cross-disciplinary practices and new aesthetic vocabularies. Creative usage of the various local spaces was part of building a shared understanding, working towards a shared goal, and affiliating with a shared value system. Various site-specific art interventions led to the creation of new local craft products and business opportunities. The project also invited sponsorships for supporting the school, and Hamdasti’s presence in the area led to other beneficial pragmatic outcomes. All the artists used local materials, tapped local skills, used local labor, and worked in close collaboration with local craftspeople (Figure 7).

At the same time, the site-specificity in project Hamdasti emphasizes the social integration of the community, which also comes under the category of community-based site-specificity. The project located in Chitpur was one such instance where social networking was directed towards rediscovering and rejuvenating the locality by involving residents and the city’s artist community in exploring local history and public spaces. In this context, I recognize that this should be the fundamental intent of the community-based site-specificity where the members from the community will be labyrinthine in the process of art-making.

Hamdasti does not explicitly focus on gender, but some of their interventions are based on feminist concerns. Bengali culture and urban middle-class public life includes adda, i.e., informal gatherings for open conversation, leisurely or animated discussions in public spaces – a social practice that is predominantly male in its modern form. Women from this class follow the custom of meeting and socializing together in their own “gendered spaces” within the house.[20] The force of gender segregation became apparent to Srota Dutta when she explored how women are imaged in the pre-wedding photographs taken in locality studios for Chitpur Local II. These photographs display women as prospective brides to families seeking matrimonial matches. Dutta identified local photo studios keen to participate in this project; some of these had been operating in Chitpur for almost a century. She facilitated interactive sessions between the male photographers and their female subjects and collected narratives from families involved in the complexities of seeking and offering brides in this manner for traditional arranged marriages. Dutta used these studio photographs in a public talk on gender issues; she also hosted three related public events at different venues – a local home, a local library, and a local photo studio – attended by the neighborhood women, local photographers and interested residents (Figures 8 and 9). While the intervention was successful, Dutta had initially struggled to find participants through casual encounters as women were rarely visible in public, and most local men refused to tell her where and how to meet them. Later through in-depth conversations with local shopkeepers, she learned that Chitpur’s middle-class women are not often seen on the streets.

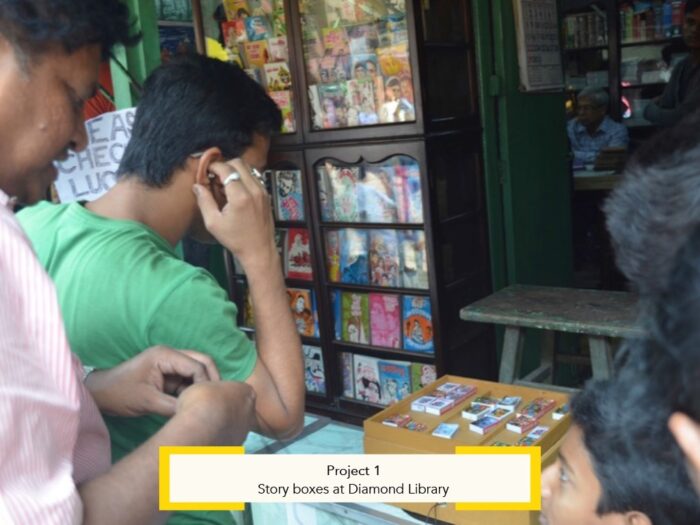

Through regular workshops, residencies, community events, festivals, open houses, exhibitions, public talks, and so forth, Hamdasti strengthened its core strategy of networking as widely as possible to make its presence felt in order to make its creative work more and more familiar to the local public, to reiterate its commitment to the locality, and to expand the projects incrementally to direct and indirectly involve more people as well as the wider artist community. During Chitpur Local I, Hamdasti had three interventions running simultaneously, all within a 100-meter stretch of Chitpur Road. The student participants were divided into groups, but they could move between interventions if they wished. The projects were the Story Box created by at Diamond Library and the Memory Game created by Nilanjan Das and a small pop-up museum in Chayanika Dey’s courtyard, created by Varshita Khaitan who involved students and assigned them to go around the community and ask people what they thought a Chitpur museum should contain. As part of the intervention, the students visited Jorashako Thakur Bari, the ancestral home of the Tagore family, which is now a heritage building. They had never visited a museum before, so this was part of their learning – to experience a museum in material terms and understand why museums are necessary. Khaitan worked with local bamboo craftspeople to make shelves for the pop-up museum. When it was ready, people brought objects to set on the shelves and narrated stories around the objects to the local audience. After initial suspicion and hesitation on the part of the residents, and the need for intensive persuasion by Hamdasti, over time the locals became to a great degree the co-creators of each intervention and eager to share responsibility for decisions, enactments, and outcomes.

The community also began to create room for the artists who introduced new practices and aesthetic vocabularies in the second phase of the project. Here, the open interaction became central in the creative process that denies the formal method of art-making. For instance, Anuradha Pathak was invited to use the dalans of local homes as community spaces for cultural activities, such as carom tournaments and workshops for making paper lanterns. Each intervention in its way attempted to facilitate encounters with the unfamiliar, and to alter the participants’ perceptions of themselves and their habitual relationships to the locality, and the festival format allowed people to participate together.

For Chakraborty, aesthetics are not just about form or philosophy, but about the granular truths of lived experiences that shape perception and visualization. The public art festivals were efforts in community building, but also attempted to change people’s perceptions about art, and about what was possible through art, including the possibility that a neighborhood could actually see the reflection and transformation of itself through art interventions. “There was no singular narrative, no unifying theme; the interventions are a means to enable different points of view.”[21] She remarks that it is more important to question hierarchies – i.e., who has formal “training” as an artist, who is seen as “skilled” or as “unskilled”, who is a “legitimate” artist/who is not, what is deemed “good” art, and what is not. “Form should be a means by which people encounter the unfamiliar, engage with their familiar context or with familiar others in a different way; and through this new engagement find themselves in a new relationship to the context and to others, for a moment.”[22] She notes that the unconventional use of form refutes and resists typical ideas “about the creation of art and about creators of art” and it is “very refreshing to see what emerges through creativity of ‘untrained’ people. The result might not be ‘beautiful’ in the traditional sense but it is powerful because it has arisen due to, and through, the defiance of aesthetic expectations, including normative expectations of form.”[23]

Chakraborty has been central to the project right from its inception, and her initial role as an artist has evolved to now include project management, fundraising, and creating new spaces for engagement. Another essential function is to engage with the larger community of artists in the city and link them to the collective in different ways. Hamdasti is collaborating with artists across disciplines and genres, as well as a range of civil society actors including local clubs, the Kolkata police, human rights activists, and NGOs interested in working with artists “not only as part of social awareness campaigns but also for the sake of the arts, to support the artist community and practitioners who do socially engaged creative work.”[24] Her concept of community art involves reaching as many people as possible by expanding the projects into the different areas of the locality, utilizing different media, and ensuring the participation of a broad demographic. She reiterates that dialogue about art practice is very important, and that community input about the project must always be taken into account so that Hamdasti can attract new participants and deepen its understanding of ground realities.

3. Project: Blank Noise, Bangalore, Karnataka; online via the Blank Noise Blog (2003 – present)

Located in Bangalore, one of India’s largest and most influential technology hubs, Blank Noise is a feminist activist project founded in 2003 by Jasmeen Patheja in response to her personal experience of street harassment, (depressingly referred to by the absurd archaic descriptor “eve-teasing”) during her undergraduate studies in art and design in that city. The project opposes all forms of gender discrimination and violence against women and supports the assertion of multiple forms of gender identity/orientation, and mobilizes women towards self-affirmation, towards confronting their fears, and taking steps to protect themselves. Blank Noise activists use public spaces in different cities to stage protests, to perform, and to campaign against sexual assault, victim blaming, domestic violence, street, workplace and campus harassment, misogyny and other forms of gendered abuse.

Interventions in the digital realm take place through a website and through a blog co-created by activists, journalists, writers, and cultural practitioners. An important contribution to gender discourse, the blog is an effort to raise public awareness and bring about a substantial alteration in prevalent social prejudices, attitudes and behavior that humiliate, harm and traumatize women. The blog documents issues around gender violence and channels voices against gender injustice by collecting testimonials from women who have experienced abuse. The platform is also used for strategizing, collaborating, and building activist alliances. The Blank Noise website affirms the act of empathetic witnessing through themed podcasts, and offers group solidarity through interventions such as “listening circles” in different locations, as well as multiple ways of activist connection and participation.

Patheja states that the medium of intervention in public space is “the body, a repository of memory, emotion, bearing the direct imprint of experience”. According to her, bodies are diverse, but through the intervention they become a collective instrument for bringing together the personal, the social and the political.[25] She also remarks that embodied intervention means direct presence in public space for a particular articulation, taking on the challenges of such enactment in Indian public spaces that are inherently full of physical and psychological risk for all women, across age, class and ability. The “art” that is created emerges through this social process of mobilization and enactment in a particular time and space. It is an organic, dynamic, fully embodied practice, so the public action/art “product” cannot exist without its “producers” – the physical community of activists; nor can it exist without the public – the physical community of viewers.

Volunteers are motivated to join Blank Noise not because they want to “help” the collective but because such activist articulation is important to them, an affirmation of what they have witnessed and experienced. “This is not the traditional logic of volunteering, and it is not easy,” comments Patheja, explaining that volunteers come to Blank Noise primarily because something about the activism in this group has strong resonance in their lives, and has acquired enough significance that they want to support, with their bodies, Blank Noise way of demanding gender equity, gender justice, social inclusion, social change. They commit their bodies to this work not because the issues Blank Noise engage with are important , but because these issues are important to the volunteers.[26]

Blank Noise interventions, referred to as “actions”, in public space are underpinned by an explicit rhetoric of empowerment, agency, autonomy, self-affirmation, and self-belief. “May we never have to carry that weight of silence, shame, blame for experiencing sexual and gender-based violence. We are done defending.”[27] Activists are called “sheroes” / “theyroes” / “heroes”, and group solidarity is clearly enunciated in their manifesto: “I feel safe when I am heard. I feel safe when I am not judged. I feel safe when I don’t have to justify myself over and over again. I, Action Shero, am your safe space, as you are mine. I Never Ask For It. An Action Shero builds capacity for difficult conversations. The Action Shero/Theyro/Hero is willing to be self-confrontational in walking towards their ideal feminist self.”[28]

Why are you looking at me? (2006)

Why are you looking at me? (2006) took the form of activists standing idle at traffic signals and railings on the streets with letters of the alphabet taped to their chests. hen the activists stood next to each other, the letters became the sentence “Why Are You Looking at Me?” Volunteers were mobilized through word of mouth, and this action was repeated each weekend, simultaneously, in the cities of Bangalore, Chennai, Kolkata, Delhi, Patna, and Hyderabad.

March in the City (2006),

Proposed by a volunteer, March in the City took the form of a blogathon on March 8th to mark International Women’s Day. Hundreds of people took part in this digital event, some using the blog to disclose incidents of street harassment and other kinds of violence they had been subjected to even decades earlier but had never spoken about to anyone. The blogathon was picked up as a news item both in the national and international media. People even wrote in from all parts of India and from other countries, saying they wanted to start chapters of Blank Noise in their own locations.

Talk to Me(2012)

Talk to Me took place in a lane outside the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore and was held by Blank Noise volunteers, including women who were studying there (Figures 10 and 11). This project focused on the acute problem Srishti’s women students faced almost daily while negotiating a particular public space lane (referred to as “Rapist Lane”) outside the Institute – a lonely dark alley that was unsafe due to the presence of men, sometimes drunk, who often loitered there for the purpose of harassing the women walking through it. The activists placed tables in the lane, inviting the men to sit down with the women they were harassing and have an empathetic conversation over tea and snacks, listen to one another, and try to understand each other. Following the session, the activists offered each man a flower. This intervention continued for a month, after which the lane was renamed Safe Lane” because the men no longer used it to target women.

Meet to Sleep (2016)

Meet to Sleep (2016) was co-hosted by Why Loiter (Mumbai), Girls at Dhabas (Karachi, Pakistan), and activists in the cities of Pune, Bombay, Bangalore, Delhi, Jaipur, and Hyderabad. The participants undertook an action, radical in context of social conservatism and male privilege. They “slept” for short periods in open parks across the country, asserting their presence in public, claiming public space, and emphasizing the right to freedom (Figure 12). In 2017, Blank Noise linked up with 22 organizations and collectives across India in a Meet to Sleep action to mark the passing of five years since the unconscionable gang rape and subsequent death of young physiotherapy student Jyoti Singh, named “Nirbhaya” (Fearless Woman) by the media before her identity was revealed. The action was repeated in 2018.

The Blank Noise project reframes the SEA variable of site-specificity through two modes of intervention – physically in diverse urban public spaces, and virtually in cyberspace through its website and blog that document actions, archive women’s testimonials, and serve as a public repository of themed, technologically enabled conversations and connections.

Blank Noise’s actions create a complex, inseparable affiliation between the site and the intervention. Without the physical presence of participants, the site-specific embodied artwork cannot be accomplished. This direct method has an immediate, visceral impact and is thus more powerful than indirect digital interventions, even though the physical artwork is transient and digital content can exist presumably forever. However, the physical artwork has limited viewership, while the virtual platform is able to reach many more people and generate dialogue through bringing together different communities and circuits of response. The first blog posts enabled a growing community of people interested in the issues Blank Noise engages with to connect with each other in solidarity online, and to affirm their own desire to change social attitudes towards women and change gender narratives. Other people got to know about the blog through word of mouth, and then joined that larger pool of communicators. The bloggers formed a community, and conversations from the blog continue offline in parks and public spaces.

Through its physical and digital interventions, Blank Noise has generated new social relationships among its participants, and is an example of how the variable of gender facilitates a particular “production and structuring” of community space.[29] Patheja points out that the collective builds “depth of conversation” through cyberspace the same way that it builds “depth of action” through physical interventions in public space. She says that it is not enough just to perform the action in public space, whatever that space might be. Through the blog we document how we felt about the experience of intervention, share our views. On the basis of what we learnt through that sharing, another action would be conceptualized and developed.[30] In tactically enabling women’s self-expression, sociality, autonomy, and agency through non-purposive “loitering”, for example, Blank Noise offers a new site of engagement with the politics of both feminism and citizenship.[31]

Patheja clarifies that her concept of intervention “is not set in stone” and that the collective’s “ideas for action” do not emerge in isolation, but are “sparked” from listening to people’s testimonies, suggestions, proposals.[32] The art/social practice is shaped through “collective input and labor” and rests on “community participation, engagement, ownership, and public presence.”[33] Blank Noise interventions are not a conscious “demonstration” of practice, nor are they a defined “result” of practice – they are an instrument for women’s self-affirmation and an assertion of women’s rights. In wider terms, they are directed towards the transformation of social conscience with regard to sexual and gender-based violence.

Through physical and digital interventions Blank Noise confronts the narrative of fear which women in India so deeply internalize vis-à-vis the negotiation of public space – fear of standing alone, fear of meeting men’s gaze, fear of harassment, fear of verbal abuse, fear of being stalked, fear of being assaulted. Women also fear repercussions within domestic space for not obeying patriarchal mandates to return immediately after completing whatever task took them outside the enclosure of the home. “Given all this, for a woman to just be standing idle, apparently without purpose, in public space is a very brave act, a remarkable counter-narrative, and a singular challenge to the prevailing gender norms in India,” comments Patheja.[34] Activists’ silent embodied presence in public space thus may be read both as a physical testimony and an empowering speech act. Blank Noise lays equal emphasis on the other crucial aspect of testimony – the act/action of bearing empathetic witness, and sensitizing and training people in this act/action. “Blank Noise and its #INeverAskForIt mission are committed and invested in building our collective capacity to be listeners. It isn’t enough to ask or ‘encourage’ survivors of violence to speak when the capacity to listen has not been taught.”[35]

Patheja describes Blank Noise as “quite fluid”, in that people participate when they can, and continue to be a part of the community, a friend of the community, even when they are not directly involved in the current interventions. The group initially formed of its own momentum; the members were committed to collective work, and contributed significantly to the process of building dialogue and interventions based on lived experiences around gender harassment, discrimination, injustice, patriarchy, misogyny, and all forms of direct and indirect violence against women. She mentions that those idealistic young people are now in their late thirties/early forties, they have families, they have careers, they have other priorities, but many remain connected to the collective and support our work. Her role is to facilitate the connection; she is a kind of thread linking those earlier participants with Blank Noise as it functions today.[36]

Patheja reiterates that the collective regularly works with feminist allies in solidarity with their particular causes, often reinforcing their allies’ public interventions without Blank Noise volunteers necessarily being visible themselves. The offering this kind of continued support, seen and unseen, is crucial to our sense of who we are, to the inclusiveness of their practice, and to the trajectory of the activism that tries to confront gender-related crisis and serve as a safe repository for, among other things, the therapeutic articulation of trauma. The socially engaged art that emerges through the embodied and digital practice pushes for a new imagining of public space: ideally, the kind of public space that in all ways will always be safe for all women.[37]

Conclusion

Art historians note that women artists have been on the ascendant in India since 1970 and that their practices “have strongly challenged the bourgeoisie notions of the divide between the private-public sphere and the autonomy, nationalism, and subjectivity.”[38] The three women artists discussed in this section use different methodologies to navigate complex, multilayered public spaces that are, as Massey has remarked, always under construction.[39] Their diverse interventions are based on dialogic and collaborative modes, and on the successful relationships of trust that they build over time with the communities within these spaces. Their creative engagement firmly rests on the process of “sharing understandings, reactions, decisions, and thoughts by the participants.”[40]

Altaf is an early practitioner in the field of SEA in India. Her shift from the metropolis of Mumbai to rural Bastar was inspired by Bhopal-based artist J. Swaminathan whose primary objective was to collaborate with indigenous practitioners. Altaf travelled alone, always a challenge for women in India, through Bastar to meet the Adivasi community, build relationships with local artists, experience tribal art and culture, and root her own creative trajectory in the villages. As evident in the acronym DIAA, dialogue is the fulcrum of Altaf’s practice. DIAA is not a studio space for the production of individual artworks for exhibition purposes – it is a cultural space, hosting dialogue-based activities and events that foster critical thinking and reflection. It is through dialogue that she and her colleagues developed an understand of each other’s artistic premises and positions, and effectively communicated on art and other issues. For example, they reflected on personal limitations and conditioning vis-à-vis gender bias and sexual hierarchies, worked out ways to develop a critical vocabulary, and worked to research and redefine the “art vs. craft” and “artist vs. craftsperson” dichotomies in the context of canonized art history in India. Through dialogue the group also explored the politics and ethics of representation, self-representation, the language produced through art practice, the effects of art practice, the process of self-scrutiny through art practice, and the evolution of arts discourses through assimilation of community input and indigenous/traditional knowledge.

Altaf is critical of the emphasis that continues to be laid on production, technical efficiency and aesthetic particulars in the context of art, at the expense of dialogue. This emphasis reduces the possibilities of meaningful exchange between artists and audiences from different backgrounds and radically different levels of enfranchisement. It also forecloses the chance to create alternative art spaces, i.e., outside the boundaries of cultural institutions. As one such alternative space, DIAA has expanded dialogue-based critical discourse/ generated a discursive community through seminars that have been attended by artists, cultural theorists, art historians, art critics, researchers, students, cultural and political activists, local municipal officials, school and college teachers, poets/writers, theater groups, farmers, technocrats, NGO advocates, and journalists. Committed dialogue has led to deep insights into the “outsider” assumptions and conditionings that obstruct possibilities to learn and explore. It has also oriented “outsiders” to different cultural sources and to the value systems, material knowledge and symbolic imaginary of Adivasi communities.

Chakraborty’s interventions are not explicitly gender-focused, but there is a strong effort to involve women, including homemakers and teachers, within the conservative locality. She has invited women artists and researchers from outside Chitpur to collaborate with the project, and this has encouraged more participation from local women. The project has built strong local support through systematic presence and ongoing informal communication with the community, so there is generally a good response to calls for participation. As the project expands, the collective build new relationships from scratch at each new site – getting the community involved, convincing traditionalists to create room for new collaboration, getting artists interested in local practices and in creating an aesthetic vocabulary, and in wider dissemination of the knowledge that arises through collaborative work. The collective has successfully enabled two things. First: the formation of new community networks that then host and support the art in their locality. Second: Each intervention in its own way tries to create encounters with the unfamiliar, presenting interfaces and interactions that can change local people’s perception of themselves, of the locality, and of their existing relationships to it and to each other.

However, the project does not show evidence of focused dialogic engagement through which the artworks can organically emerge in the material environment of Chitpur. The intervening artists or groups of artists bring their preconceived ideas, aesthetics into the project and communicate these to the community, which then participates in the collective execution of the ideas. The artists’ voices dominate, and while events are documented on the project website, there is no documentation of creative dialogue between artists and the community, between artists and participants, between participants, and between participants and the community.

Patheja’s political and creative trajectory is thoroughly feminist, challenging India’s patriarchal systems through activism that is both embodied (physical interventions) and disembodied (virtual interventions). Her practice invokes the possibility of gender affirmation, gender justice, and gender equality – i.e., enables people to imagine what today might actually be dangerous to imagine in India, and in many other parts of the world.

Patheja’s activism pivots around ways to build much deeper, inclusive connection with women across the spectrum, in order to develop new sets of questions around which interventions can be shaped. The Nirbhaya atrocity in 2012 made her sharply aware of the limited, fragmented and incomplete nature of existent conversations around the more extreme forms of violence against women in public spaces. She points to the urgent need to make socio-cultural and discursive space for the expression of women’s fear, the need to expose the way women are conditioned to fear certain kinds of male predators, the need to expose the limits of this kind of understanding, and the need for women to have direct dialogue with those very predators. Patheja also points out that regardless of gender/sexual identity, the project’s online and real-time activists and those who want to join project actions are already in dialogue with themselves, exploring their own complex internal relationship to the body and gender issues, their own gendered personal, family and/or community narratives, and their own way of navigating all or part of identity concepts and identity politics. Participating in the project’s embodied or virtual interventions might be just one aspect of this deeper self-scrutiny.

The primacy of social context/community as the core of Socially Engaged Art practice has compelled contemporary artists to reflect on personal identity and self-definition in relation to the contexts/communities they are creatively engaged with. As mentioned earlier, the artists discussed in this chapter do not consider themselves to be educators, instructors, pedagogues or authorities of any kind. Altaf sees herself as a mediator/interlocutor, primarily a facilitator of dialogue between local and outside artists, between local participants, between artists and local participants, and between artists, local participants and the larger Adivasi community. Chakraborty’s work meshes across multiple areas – project manager, fundraiser, creator of spaces for critical reflection, administrator, and link between artists and the community. Patheja has moved beyond her early role as a visualizer or creator of interventions to the more general one of planner, team-builder, interface and bridge between various segments of the project, its past and past activists, feminist allies and networks, and the wider community created via the project’s digital platforms.

Sreejata Roy is a Delhi based artist and academic who has completed her practice-led PhD from University of Technology, Sydney, Australia in 2024 and practice based Mphil in Media Art from Coventry School of Art and Design, Coventry University, UK 2005. As an artist interested in community-related projects, Sreejata has been using classical/conventional and mixed and digital media to produce various art forms, engaging the community. Roy’s current art practice in Delhi (2007-present) involves working with young women for over a decade through Socially Engaged Art practice connecting the ideas of public spaces in many sprawling and congested marginalized colonies inhabited by generations of migrants from the neighboring rural territory.

Roy was awarded a “Public Art” grant from the Foundation of Indian Contemporary Art (FICA) in 2008 and completed reshaping a community park in one of those marginalized neighborhoods. The project is part of the Public Art Archive published by International Public Art (IAPA). Apart from FICA, she has been awarded other prestigious scholarships in India, including a National Scholarship, from the Ministry of Defense, New Delhi, 1993, Community Art Grant, Khoj for international artist Association, 2008-2009 & 2014-2016, Art- Reach India Community Art Grant 2015-2020, SEA Grant, Kiran Nadar Museum, Delhi, 2016- 2024. At the international level, she was awarded Pro Helvetia Swiss Cultural Scholarship to work in Basel, in 2011, IASPIS, The Swedish Arts Grants, Committee’s International Programme for Visual Artists, Malmo, Sweden in 2017, Short research grant from IASPIS, The Swedish Arts Grants, Committee’s International Programme for Art-Environment-Community, 2024, Prince Klaus, Netherland Fund to develop a community kitchen with the migrant, refugee communities in low- income locality in Delhi. She also received several academic awards including Overseas Research Scholarship UK: 2000-2004, the Presidency Scholarship, and the International Research Scholarship, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia, 2018-2021.

At present, she is an Adjunct faculty in the postgraduate course in the area of SEA in the Visual Art Department of Creative Expression at Ambedkar University, Delhi. She is also a visiting professor in Visual Arts in Ashoka University. Roy is a part of Revue, an artist collective based in Delhi (2008-present) and has collaborated on various community and public art projects in India and abroad for several years. Her scholarly papers are published in many significant academic journals.

Notes

[1] See: DIAA Dialogue 2021, https://www.dialoguebastar.com

[2] Urvashi Butalia, “Foreword,” The Fear that Stalks; Gender based Violence in Public Spaces, edited by Sara Pilot And Lora Prabhu (New Delhi, Zubaan, 2012).

[3] Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage Publication, 2005).

[4] Amita Bavishkar, Demolishing Delhi: World Class City in the Making, 2006, p 1,2.

[5] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000), p. 159.

[6] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative art in Global Context (London: Duke University, 2011).

[7] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000), p. 56.

[8] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative art in Global Context (London: Duke University, 2011), p 79.

[9] Nancy Adajania, The Thirteen Place, edited by Navjot Altaf (Mumbai, India: Guild Art Gallery, 2016), p. 243

[10] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative art in Global Context (London: Duke University, 2011).

[11] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another, Site-specific art and Locational identity (London: MIT, Press, 2002), p 6.

[12] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another, Site-specific art and Locational identity (London: MIT, Press, 2002).

[13] Grant H. Kester, Conversation Pieces, Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkley London: University of California Press, 2004).

[14] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[15] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[16] Jyotindra Jain, Kalighat Painting, Images from a changing world, Publisher: Map in Publishing Pvt. Ltd. Ahmedabad, 1999

[17] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[18] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[19] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[20] Shilpa Phadke, Gendered Usage of Public Spaces; A Case Study of Mumbai: The Fear that stalks; Gender based Violence in Public Spaces, edited by Sara Pilot and Lora Prabhu (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2012), p. 53.

[21] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[22] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[23] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[24] Sumana Chakraborty, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2020.

[25] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[26] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[27] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[28] Blank Noise home page, https://www.blanknoise.org/home.

[29] Shilpa Phadke, Gendered Usage of Public Spaces; A Case Study of Mumbai: The Fear that stalks; Gender based Violence in Public Spaces, edited by Sara Pilot and Lora Prabhu (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2012), p. 53.

[30] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[31] Shilpa Phadke, “Defending Frivolous Fun: Feminist Acts of Claiming Public Spaces in South Asia,” Journal of South Asian Studies, Australia: Routledge, (2020) p. 7, https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2020.1703245

[32] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[33] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[34] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[35] Blank Noise home page, https://www.blanknoise.org/home

[36] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[37] Blank Noise, interview by Sreejata Roy, 2021.

[38] Achar Deeptha and Shivaji K. Panikkar, eds., Articulation Resistance, Art and Activism (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books,2012), p. 237.

[39] Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage Publication, 2005), p. 9.

[40] Grant H. Kester, What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation, edited by Tom Finkelpearl (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2013).