Socially Engaged and Public Art in India: A Chronology from 1990 to the Present (Part 1)

Sreejata Roy

This is the first of two essays which will examine art projects developed in public spaces in India since the 1990s. The second essay will appear in FIELD’s Winter 2025 issue. I’ll begin with a synoptic history of art practices and interventions in Indian public/social spaces over the last century, from the 1930s and 1940s into post-independence modernism and then into the digitally-driven contemporary moment. I then discuss the two phases of the art projects that have developed beyond the conventional art studio in public space. The first phase, 48°C Public.Art.Ecology (2008), was the first-ever large-scale, site-specific themed public art festival in India, which was independently curated by Pooja Sood. [1] I draw on my detailed interview with Sood (2020), as well as a documentary film about the festival (48°C Public.Art.Ecology [2008] by Delhi Green Ewafarence Duration) to enrich my examination. This is followed by my analysis of art projects in public space by four contemporary artists (Ravi Agarwal, Sheba Chhachhi, Atul Bhalla and the collective WALA comprised of Akansha Rastogi, Sujit Das, and Paribartana Mohanty). [2] This analysis is based on my interviews with these practitioners, conducted both in person and online. I’m focusing on these particular curators and artists because their works are among the earliest examples of projects in public space in India and also among the first to involve engagement with local communities. In addition, since the 1990s they have all continued to innovate and to extend their practices beyond the conventional boundaries of art studios, galleries, museums and cultural institutions.

In the second phase of the essay, which will continue in the forthcoming issue, I will discuss three case studies of ongoing Socially Engaged Art projects in three locations in India to illustrate the development of SEA in India between 1990 and the present. Three projects discussed in the second phase, fall directly within the Socially Engaged Art category, with the practitioners primarily using collaborative and dialogic methods in their work with disenfranchised communities to recreate and reclaim these communities’ existent social and public spaces. The first project is DIAA (Dialogue Interactive Artists Association), founded in 1997 by Mumbai-based artist Navjot Altaf, and is located in the tribal region of Bastar in the state of Chhattisgarh in Central India. The second project is Hamdasti (“partnership” in Persian), founded in 2014 by Kolkata-based artist-curator Sumana Chakrabarty, who works at Chitpur Road in Old Kolkata. [3] The final project is Blank Noise, founded in 2003 by Bangalore-based multimedia artist/photographer/feminist activist Jasmeen Patheja.

I channel my analysis through the key concepts introduced in my practitioner-interview questions. [4] The interviews constitute part of my primary data, falling within the broad theoretical categories of Collaborative/Dialogic/Participatory Practice, Site-Specific Art and New Genre Public Art. My analysis maps the concepts emerging from the primary research data onto the broader formulations of socially engaged art discourse in order to frame engaged art in India–a jagged, complex, and rapidly mutating field that regrettably remains under-documented and under-studied, and about which very little research is publicly available even today. I conclude this essay with an analysis of the ways in which these practitioners have used diverse methodologies to move out of conventional studio/institutional spaces and directly engage with communities in public space.

The Historical Background of Engaged Art in India

As observed by art historian Geeta Kapur, post-Independence Indian art is characterized by two trends. On the one hand “there is a sustained attempt to give regard to indigenous, living traditions and to dovetail the tradition/modernity aspects of contemporary culture through a typically Postcolonial eclecticism” and on the other hand “there is a desire to engage from overarching politics of the national by reclusive attention to formal choices that seemingly transcend both cultural and subjective particularities and enter a modernist framework”. [5] Pre-Independence Indian art tended to be deeply political, influenced significantly by Left politics as well as the ongoing nationalist struggle against British rule. Art in public/social spaces during this period took various forms and had a critical function, both as an instrument and platform for political and social dissent, and as a method of uniting people across the country by urging resistance to the colonial adversary. A leading and very active group in this anti-imperialist cultural movement was the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which played a substantial role in engaging the urban and rural working classes by presenting a range of themes, from land rights to social injustices and political oppression in theatrical form. Through IPTA, groups of singers, dancers, actors, artists and pedagogues travelled to every corner of the country, infusing novelty and experimentation into all fields of creative practice and substantially building solidarity nationwide. [6] The IPTA-dominated decades are considered the dawn of art as a public/social practice in India, and IPTA remains “the most valorized movement of ‘revolutionary’ artists to this day”. [7]

During the Post-Independence period, IPTA’s influence began to wane and declined steeply after 1950; but as a cultural organization it successfully catalysed the birth of progressive amateur theatre in India. From the 1950s through the 1980s, many groups were motivated to produce work foregrounding social and political issues. This is exemplified by Bahurupee, Nandikar and People’s Theatre (active in Bengal) and Prithvi Theatre (active in Bombay). Prominent dramatists such as Habib Tanvir (a former IPTA member) and Badal Sircar (member of the CPIML: Communist Party of India Marxist-Leninist) were pivotal in taking traditional and experimental theatre arts/performance into public urban and rural settings. Tanvir, who founded the Naya Theatre Company in Bhopal (Central India), is known for his paradigmatic reworking of traditional folk forms through sustained engagement with indigenous communities in the tribal region of Chhattisgarh in Central India. Sircar, founder of the troupe Satabdi and author of the groundbreaking play Ebong Indrajit (And Indrajit), took drama from the proscenium to the street. Equally influential was the young director-actor Safdar Hashmi (member of CPIM: Communist Party of India Marxist and founder of the IPTA-inspired theatre troupe Jan Natya Manch). Hashmi was noted for radical street theatre, with its dialogic possibilities magnified through adept spatial usage. This means the way the physical locations in which he uses these spaces “adeptly” innovates, improvises and shapes an inclusive, participatory experience for the audience. For example when Hashmi performs near or in lanes or in a small park or street corner—sites that exude tight, messy, intricate, confined spaces in the labyrinth of industrial sites or working-class neighbourhoods—he moves around the built environment and thus spontaneously expands the “stage” of the street. He engages the crowd in a very direct manner, speaking their lines directly to people in the front of the crowd, face to face, as if expecting a response. If there is a response, it might be worked into the script; the performer improvising in the moment.

In terms of method, both Sircar and Hashmi deliberately reduced the gap between performers and audience, reaching back to Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, a form that “sought to reduce the distance between actors and spectators. This emphasis on proximity was crucial to myriad developments in the avant-garde theatre of the 1960s”. [8] After the untimely and tragic death of Hashmi, Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT) was founded in his memory by the artist collective, with a mission to generate public discourse on art, and art as a platform for the enunciation of dissent when democratic rights are threatened. SAHMAT artists, journalists and academics from all over India organized mobile exhibitions and performances in urban public spaces, with a commitment raising socio-political awareness through a spectrum of art practices. To this day, for practitioners across the arts spectrum in India, Hashmi remains a potent symbol of passionate conviction and anti-authoritarian courage. [9]

The 1990s saw a new turn with regard to cultural expression in public space, chiefly manifesting through contemporary visual art practices, installation, sculpture, video art and performances in metropolitan cities. These artists were influenced by what Kapur describes as new, secular modes of postcolonial identity-making that incorporate exceptionally diverse and ancient folk and local art forms. Undistorted by the colonial cultural imprint, these “timeless” forms, through their intrinsic strength, have in specific ways countered, and sometimes even undermined, the dominant narrative of modernity. [10]. Below, I provide a brief survey of work produced during this period. Vivan Sundaram’s Structures for Memory (1998) is an 80-foot narrow railway track installed through the Durbar Hall of the Victoria Memorial (a white marble colossal monument built at the time of colonial rule in the early twentieth century) in Calcutta. The work reconstructs the process of British India’s modernization project of Indian Railways by multiplying the definition of space. Subodh Gupta’s Untitled (1999) is a performance piece in which the artist laid down in public and covered his body with mud, an indigenous material, in the abandoned factory space in Modinagar, UP. M.S. Umesh, Sonam and Srinivas Prasad’s Earth-Work (1996), is a massive site-specific art installation wherein the artists created signs in the public ground as markers of ongoing traces between nature and the city in Bangalore. Beginning in the 1990s a different approach was taken in South India, when the Kerala Radicals reestablished the idea of group projects creating an informal and open platform for discussion, a project that Kapur has commented evokes “the fetish in magic, art and commodity”. [11] Additional contemporary performance, visual and installation artists include: New Delhi-based conceptual performance artist Inder Salim who experiments extensively with engaging the public space, New Delhi artist Sonia Khurana works with lens-based media and the moving image, sound installations as well as performance in public spaces, Delhi performance artist Nikhil Chopra juxtaposes his performances in public space with drawings, paintings and sculpture, a gesture that connects gallery work with the world beyond. Bangalore photo and video-performance artist N. Pushpamala focuses her practice on the subject in images that critique female stereotypes in India. Open Circle Group is a collective founded by the Mumbai-based artist duo Sharmila Samant and Tushat Joag and video artist Shilpa Gupta, together who engage in environmental critique and interrogate urban socio-political issues. [12]

Since the 2000s a number of new non-profit, cultural and arts-management organizations and spaces, supported through mixed funding sources, have emerged in Indian metropolitan areas (New Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore). The most prominent example is Khoj International, a non-profit arts organization located in Delhi. [13] Initiated in 1997 in New Delhi by Pooja Sood and a group of artists, Khoj has been highly successful from its inception to the present day through interdisciplinary collaboration and experimentation with creative practitioners to create space for new possibilities for art-making. (Ravi Agarwal, Atul Bhalla and Sheba Chhachhi, three of the eight engaged art practitioners interviewed for this essay, have been recipients of Khoj support). Sarai, a programme of CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi), was initiated in 2000, and focuses on new media, the public domain and the politics of information. [14] FICA/Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art facilitates the work of individual artists (WALA Collective was interviewed for this essay and have been recipients of a FICA Public Art Grant). [15] The last two decades have also seen the emergence of practitioner-based partnerships and larger collectives, for instance CAMP (comprised of artists Shaina Anand and Ashoke Shukumaran) [16] and Cybermohalla [17], a collaborative project of Sarai and the NGO Ankur Society of Alternatives in Education. [18]

These larger, well-funded arts organizations and management spaces have inspired collectives such as 1 Shanti Road [19] and IFA/Indian Foundation for the Arts [20] (Bangalore); Dharavi Art Room [21] and Mohile Parikh [22] in Mumbai; art entrepreneurs such as Art-Reach India [23] and Serendipity Art Foundation [24] (Goa), and numerous smaller art foundations which today fund engaged art projects across the country. In parallel, individual practitioners such as Navjot Altaf have consistently oriented their engaged art practices towards building long-term, stable, self-sustaining participatory and collaborative projects with specific marginalized communities in peri-urban and rural areas.

1. Art in Public Space in India from 1990 onwards

48°C: A Public Art Festival in New Delhi (2008)

The independently curated public art festival 48°C Public.Art.Ecology (2008) (Figure 1) was the first event that allowed Indian artists to present their artworks in urban public spaces, and to directly connect with a general public that does not have access to city galleries or art museums. Participating Indian and international artists created works specific to themes of the environment and ecology. Maintaining a broad scope, the festival included nature walks, film screenings, and a symposium on environmental and ecological issues, urban space and public art. The festival brought contemporary art out of the conventional, protective boundaries of studios, galleries and museums into the rough, dense, disorienting space of India’s cosmopolitan capital city and its enormously varied public of nearly 17 million inhabitants (at that time; the numbers have since grown). This demographic has likely never been exposed to the concepts, aesthetics and material forms of such art.

In this section I draw on a 2020 interview with festival curator Pooja Sood to examine how 48°C influenced socially engaged art practice in India. Our conversations revolved around several key concepts. In response to my question about her understanding of the term “site-specific,” one such core element, Sood clarified that she intended to use the city’s diverse material environment to build awareness about global climate change and the ongoing environmental crisis through the presentation of themed artworks in public space. Hence the festival installations were intentionally positioned at sites conveniently accessible via the Delhi metro, specifically the subway system’s Yellow Line, a route that traverses New Delhi, Central Delhi, and Old Delhi, i.e., linking the modern city with its colonial and historical areas (the line has since been extended much further in both directions).

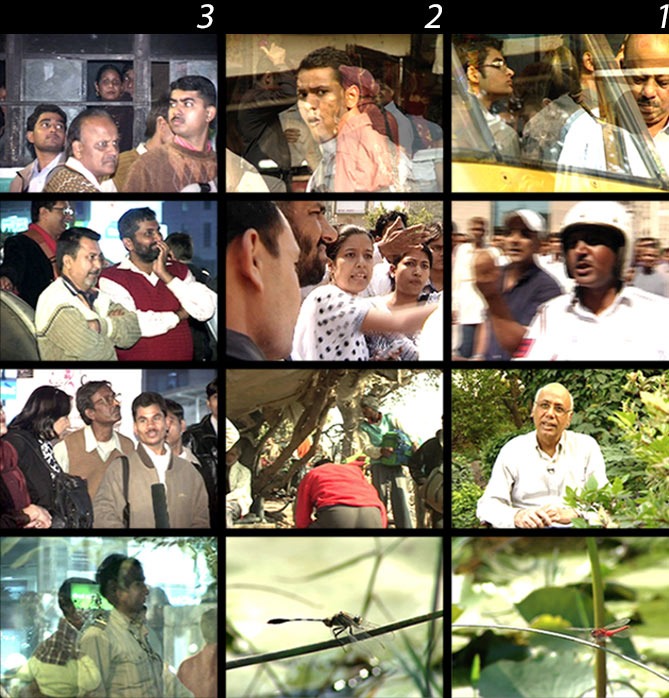

Sood discussed three installations in Central Delhi that directly presented the theme of the destruction of nature in the city. At the Mandi House roundabout, which faces the Natural History Museum at one end of Barakhamba Road, Ravi Agarwal’s installation Extinct (Figure 2) took the form of a light box that presented the near-extinction of the Indian vulture population, primarily as a result of the birds feeding on carcasses of cattle that had been treated with Diclofenac, a common anti-inflammatory drug lethally toxic to vultures (it is now officially banned for veterinary use in India, Nepal and Pakistan). Barakhamba Road, a major street leading off the Mandi House roundabout, was the site of Krishnaraj Chonat’s installation Crane+Tree (Figure 3) on the theme of deforestation in relation to urbanism. Placed next to a large, deserted, decaying colonial bungalow, the installation consisted of a dead tree suspended from a construction crane. Pointing to the fact that many imposing old trees along Barakhamba Road had been cut down to make space for the Delhi metro rail, it signified the enormity of irreparable, irreversible loss as well as other violent changes. These include the rapid sale of private properties of historic value for exorbitant prices, combined with the brutal felling of thousands of trees, some over a century old, in Delhi in the name of “development;” the claiming or clearing of open/green spaces all over the city for the laying of metro tracks; and the municipal eviction and bulldozing of slums in order to accommodate the construction of skyscrapers, high-rise apartments, technology zones, business centers and other commercial projects. The other end of Barakhamba Road opens into the ever-busy major business hub of Connaught Place, at the center of which is Palika Bazar Park, a large open space embedded within the wide orbit of colonial-era shopping arcades. The park was the site of Navjot Altaf’s work Barakhamba (Figure 4), which explored the tension between ecology and “development” through a set of three large video installations, showing members of the public in conversation with the artist. Generally critical of what they experienced as short-sighted policies of urban planning and architectural design, people shared their views, visions and anxieties vis-à-vis changing city spaces, and the effect of these changes on their lives, livelihoods, localities and the city’s environment.

The festival’s two interactive water-themed installations were located in historic Old Delhi at Chandni Chowk and Kashmere Gate. For centuries both sites have been associated with the river Yamuna, the main source of the city’s water supply, and is now highly polluted with raw sewage, industrial effluents and other dumped toxic waste. [25]

Sheba Chhachhi’s installation The Water Diviner (Figure 5) was located at the old public library in Chandni Chowk, opposite the Old Delhi Railway Station. The artist was inspired by an 1850 city map that provoked her to research the history of water in the area. The map indicated that the Yamuna once flowed right across the road from the site, and Chhachhi conceptualized the installation as an immersive experience that was simultaneously a layered material archive of the site. The Water Diviner consisted of a light box showing the 1850 map with roads and railway tracks superimposed upon the now obliterated Yamuna waterways. Divination is the technical term for the practice of intuitively sensing and locating a hidden or underground water source. Here, Chhachhi, the “water diviner” symbolically excavates and re-inscribes a river that has retreated over the past four centuries, exposing a vast flood plain that supports many underprivileged communities engaged in subsistence agriculture and other precarious livelihoods, and that is now being assiduously “developed” into varied forms of real estate and other commercial mega-projects. The installation was augmented by thousands of old discarded library books and other documents that had been tossed into a disused colonial-era swimming pool under the library. A silent three-minute video loop based on photographs by Umeed Mistry projected mythological stories about water. Using the river to invoke imperial genealogy, the past and present city and its diverse past and present communities, the artist wove together layers of cultural memories around the subject of water, its natural and artificial repositories, its current usage and its ongoing exploitation.

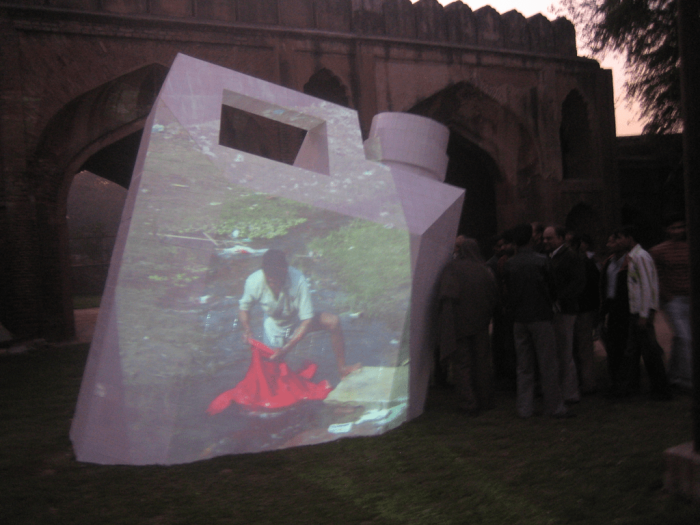

Sited at Kashmere Gate, Atul Bhalla’s installation Chabeel (Figure 6) consisted of a large white vessel shaped like a jerrycan, sculpted from sand, cement, ceramic tiles, plywood and recycled paper, with a video projected on its surface. Bhalla intended to invoke the fact that a few centuries ago the Yamuna, now a few kilometers distant, flowed by the Kashmere Gate itself. Displaying stickers with the Hindi text aap ne kabhi yamuna to dekha hai? aap ne kabhi yamuna to chhua hai? (Have you ever seen the river? Have you ever touched the river?), Chabeel sought to remind viewers that the water in city taps, indispensable and taken completely for granted, is drawn from a river shockingly polluted and degraded. During the festival the vessel was also repurposed as a kiosk, serving the public with sweetened water and lassi in the manner of the traditional street rite that marks religious celebrations in North India. The drinks were served in small glasses sculpted from the same materials as the large vessel. This mode of physically engaging viewers enabled the artist to transform his static installation into a dynamic participatory performance.

Sood noted that the project Motornama Roshanara (Figure 7) by CAMP (Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran) depended on a different notion of site-specificity. Here the artists recovered the lost micro-history of the once-thriving industrial belt at Roshanara Road in North Delhi through direct engagement with the local community of cycle-rickshaw pullers. The area includes the green space of Roshanara Bagh, a Mughal-era garden that is today one of Delhi’s biggest public parks. It was laid out in 1650 by the second daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan, princess Roshanara Begum, whose tomb at the site lies within an ornate heritage pavilion that was retained in its original form when the rest of the park was re-landscaped and “modernized” during colonial rule. Roshanara Road flourished for decades post-Independence; its commercial prosperity resting on a large base of labor underpinning the local economy. Upper classes frequented the markets and restaurants and the Palace Cinema. People from all walks of life were a part of a vibrant culture which disintegrated after the government’s forcible shutdown of all the local industries, including motor repairing factories, flour mills and the important seed market, under “anti-pollution” laws passed by the High court in the years 1996 and 2000.

A significant demographic shift occurred after the industrial shutdown between 2002 and 2004 in Delhi. While licensing cases and other long-drawn litigations between the state and factory owners continued in the Supreme court, a large community of migrant cycle-rickshaw pullers took up residence in the area, confronting the daily reality of police violence and the local resident association’s opposition to their presence. [26] But the community stayed on and expanded, from around 20,000 in the early 1980s to about 90,000 in the current moment. The cycle-rickshaw pullers, symbolic of the pre-industrial, non-motorized era, had no permanent homes in the locality; they slept on the street or in front of shuttered shops and industrial units sealed by the municipal corporation.

For their project Motornama, Shaina and Ashoke selected twenty-five cycle-rickshaw pullers who lived around the seed market on Roshanara Road. [27] Over two months of planned workshops, the artists trained the group to serve as narrators for guided tours of the area. During these tours, the cycle-rickshaw pullers described their experience of manual labor, their physically arduous and risky work, and other aspects of local history and landscape. The tour included houses in the shadow of the new metro rail network expanding through the city, the hundred-year-old ice factory, tea-stalls, a derelict cinema hall, defunct car repair shops, an old printing press from Lahore, Pakistan, and the famous Ghanta Ghar clock tower. The tour culminated in the open natural space of Roshanara Bagh. Underscoring local perspectives on urban change, the project invoked the need for an active repurposing and renewal of a historical green area being systemically destroyed by state policies of “development”.

In any engaged art project, the logic of placement needs to be thoroughly scrutinized. The methodology underlying 48°C raises the core question of whether the festival’s installation art was truly site-specific? In other words, was it authentically engaged with the material context in which the works were embedded, or were the projects transient superimpositions on the chosen locales, and while seemingly connected, were in fact essentially dissociated from the surroundings? As Sood clarified, 48°C was spread across distinct and often widely separated sites, selected according to their accessibility via the Delhi metro, still in its early stages of development and offering limited routes. She acknowledged that the artists became involved in the settings of the installations much later, after the sites had already been chosen, and so could not really experience, or learn from, their physical environs and local publics prior to the process of assembling and placing their works. There is no denying that the artists did not get adequate time to interact with the site and its associated communities. However, the artists were helped in their decisions via a comprehensive site map developed through a year of research by the Urban Research Group, which identified the kind of social settings traversed by the metro’s Yellow Line: areas that have been traditionally inhabited by mixed communities mostly middle class, traders, small businessmen, lower middle class and also working class over a long period of time. The artists relied on this purposive cartography to plan their installations and negotiate challenges on the ground.

In this regard it seems that the festival organizers placed more emphasis on the artists’ creative expression, autonomy and processes rather than on the depth of their engagement with the material surroundings and fluctuating audiences within which their projects were sited. The artists treated the sites as convenient external interfaces, instruments and conduits for the artworks. In other words, the artworks did not organically emerge through the innate properties and expressive potential of each site. This approach clearly deviates from the general logic of site-specific socially engaged art work, which “focuses on establishing a complex, indivisible relationship between the work and its site,” which additionally demands the viewer’s physical presence to complete the work. [28]

Delineating the different levels of collaboration and dialogue involved in the site-specific works, Sood acknowledged that twelve days was indeed too short a time to develop any real depth of interaction with local communities around the different sites. On the level of organization and management, as an independent curator Sood formally collaborated with the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, the School of Planning and Architecture, the Urban Research Group and other essential stakeholders such as the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, Delhi Development Authority and Delhi Police in relation to permissions and regulations vis-à-vis the sites of the artworks. This level of institutional collaboration took some effort but was eventually accomplished. However, there was very limited dialogue between the artists and local communities at the installation sites, and even less direct active collaboration. Sood remarked candidly that spectacle was the only way to attract a naïve public to contemporary artworks; hence she hoped that the scale, diversity and unusual forms of the installations would impress the viewers enough to elicit all kinds of reactions.

Guy Debord notes that spectacle-based approaches reduce spectator responses, and are opposed to dialogue. [29] This seems to hold true in the context of 48°C. In her interview, Pooja observed that viewers, mostly passersby, were not the usual art lovers or familiar with contemporary art, but they were indeed curious about the unfamiliar aesthetic of conceptual work. They were generally too mesmerized, estranged, puzzled, unsettled or disoriented by the spectacle to engage in any systematic communication with the artists or with each other.

Two projects stood out as exceptions. As mentioned earlier, with Chabeel Atul Bhalla transformed passive viewers or bystanders into active and engaged participants by offering them sweetened flavoured water (Lassi) from his sculpture. The flavored water offered at the kiosk built in the sculpture did not only satisfy the thirst of the bypassers or viewers but also helped Bhalla to initiate a conversation with them regarding the site and the condition of water in the city. His work thus shifted from static spectacle to dynamic performance and engaged participation. With Motornama Roshanara, CAMP directly involved cycle-rickshaw pullers, working in person for several weeks with this community to facilitate their taking on the role of tour guides and narrators of lost local micro-histories. Both projects successfully embodied the dialogic principle central to engaged art practice as defined by Grant Kester [30], for whom talking to people face to face, on the given context and at a given site is the important and integral aspect of the socially interactive collaborative work. [31] In this context, this means that participants would directly share ideas, understandings, reactions and decisions with each other and with the artist.

As a constellation of independent projects presented by experienced artists, the chosen outdoor sites did enable artists to create large sculptural works, and hence, scale was inherent in the aesthetic logic. Scale also served to create a spectacle in order to draw in the crowds, irrespective of all class, caste and religion. It was the very first time such a massive public art event had taken place in Delhi. Unfortunately, it only lasted for twelve days and was concluded before the works could be actually become familiar, comprehended and assimilated by the viewing public. In 48°C, the curators hoped that the scale and diversity and immediacy of the artworks would elicit all kinds of responses from people from different walks of life. Sood mentioned in her interview that the people were overwhelmed and reacted with aw, shock and were mesmerised to see the monumental sculptures, videos and other installations in public spaces like streets, parks and promenades, which are very unusual in everyday life. While celebrating the process of creating a spectacle, Sood mused that the festival’s duration needed to be improved to elicit any participation from the viewers. Nevertheless, the problem lies in more than the duration of the time of the festival; it also involves attempting to connect with the public through spectacle. The 48 C Public. Art. Festival. has created alienation rather than engagement through the provoking, shocking and sometimes enraged responses. Bishop has pointed out that this kind of art in public space acts as “an elitist realm of the seduction idea of spectacle, which defines the aesthetics”. [32] However, seen in terms of a new paradigm in contemporary Indian art, 48°C did radically enable and expand viewership. Spread over multiple urban public sites, tapping into an already existent and permanent spectator pool of local people going about their daily lives, the installations undoubtedly created a massive spectacle in the city for a brief duration, and at most of the sites viewers responded energetically to the artworks. Sood gives the example of Krishnaraj Chonat’s artwork, a dead tree suspended from a crane, illuminated at night and creating a dramatic effect. People could be seen clicking photos; autorickshaw drivers stopped next to it, one exclaiming, “My God, what is the municipal corporation doing!” and another commenting that the suspended tree symbolized government oppression that was “hanging us by the neck”. The disruptive quality of the artwork induced a strong reaction in the general audience unfamiliar with such art. Modes of such raw, unfiltered, “authentic” response are rarely observed in relation to works within the protective, elite enclosures of the museum and gallery. These too are designated “public spaces,” but are accessible only to the privileged few, and managed via strict protocols of viewer compliance and decorum.

The festival introduced a new form of art in India, sited beyond gallery, museum and artist studios. The festival also initiated a new relation in art production between the artists and the wage earners. The ideas were conceptualized by the artists and executed by the wage earners on the site. Thus the process of art production was alienated from the process of art conceptualization. In this way, the art shifted from the artisanal form to the industrial form.

2. Independent Art Projects in Public Space

Site Specificity

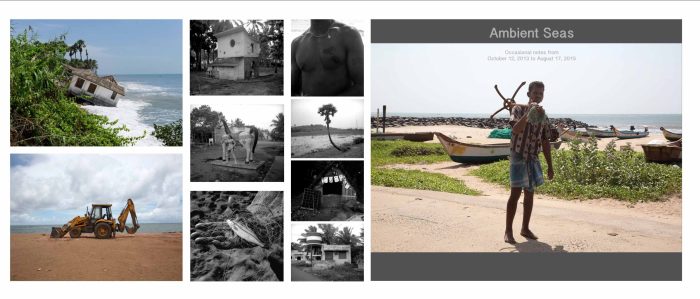

Site-specificity is integral to the projects of Ravi Agarwal, Atul Bhalla,Sheba Chchachhi and WALA (Sujit Mallick, Akansha Rastogi, Paribartana Mohanty) located mostly in the city of Delhi and its periphery. The work of these four artists draws on personal creative experience as well as wider perspectives on art in relationship to public and community spaces, ecological, historical and cultural contexts, and socio-political issues. According to art historian Miwon Kwon, “the environmental context of the location of the art has become significant and is formally determined and directed by the site itself”. [33] This may be observed in the case of Ravi Agarwal, who considers his works to be site-specific in that each work emerges from a specific topography, and articulates a clearly identified locale and community (he qualifies this with the statement that he also considers his works to not be site-specific in that they always transcend their location). He follows a research methodology that first explicitly defines his subject and then deeply mines it for the necessary materials. He prefers his work to be concretely rooted, and this preference facilitates a certain kind of local interaction with community. The work is thus contextually embedded but may lead off into more abstract directions; very occasionally there is a reversal of method, with the work germinating from an abstract idea which is then materially rendered in a particular location. This process may be observed, for instance, in Agarwal’s Yamuna Project, a river-based series of photographic works, films, installations (Figure 8) and ongoing engagements that was initiated in 2004 and continued for the next four years. His more recent water-themed work includes the multi-faceted Else All Will Be Still (2013-2015) (Figure 9), based on his engagement with a fishing community in a village on the coast of the Bay of Bengal, near Pondicherry in South India. First visiting the area as a tourist, Agarwal was drawn to the local ecology as well as to the community’s life and their deep relationship to the ocean. He returned to the site several times, gradually developing a relationship with the community and also researching the wider changes–environmental, social and economic—affecting their lives and livelihood.

For Agarwal, the rootedness of a work in a particular site endows it with a kind of authenticity that enables authentic relationships with the local community, their continuing presence of which becomes essential to his creative process. While he interacts with the community at his site-specific projects regarding his ideas, processes and intentions, the community may witness the manifesting of his artwork, and the community presence remains a variable in his research methodology, a source of information and insight. However, community participation at the time of creating the artwork is not essential, nor is their participation embedded as a material element in the artwork itself. The work subsequently exhibited in solo and curated shows in galleries and museums. In contrast, Atul Bhalla fuses the elements of site-specificity and community presence in the conceptualizations of some of his public art projects. He revisits sites inhabited by particular communities, and uses them repeatedly in different works over a period of time, so these particular spaces gain visibility; and the transformation of these sites and their communities over time also becomes more visible. Such sites, for instance the bank of the Yamuna at Jagatpur village on the outskirts of Delhi, thus acquire symbolic weight in Bhalla’s works (Figure 10), and continue to be essential and inspirational for the artist.

The elision of site-specificity and community presence is also evident in Bhalla’s installation Chabeel (Figure12) at Kashmere Gate. The work was not situated at the portal itself, as the Mughal-era gate is a protected heritage structure under custodianship of the Archaeological Society of India, and public access to it is controlled. Bhalla installed Chabeel on the open green verge by the busy road that goes through the gate’s double arches and he wanted to attract viewers unaware of the site’s rich history. His method was the purposive creation of spectacular visual dissonance, setting his contemporary sculpture against elegant architecture that invokes the grandeur of the mighty Mughal Empire. Both projects exemplify how a site itself can successfully catalyse what Bishop describes as the transformation of passive viewer participation into active viewer engagement–through interacting with the public in relation to a particular religio-cultural rite (Mashq) and through offering the public flavoured water to drink, which also draws on a religio-cultural rite (Chabeel). [35]

For Sheba Chhachhi, site-specificity is an important aspect of public art as it offers the artist the chance of direct engagement with a public or passerby or viewer who is normally present at the location, through their participation in the work; and it also offers the community the chance to be integral to the art-making process, whatever form it might take. A good example of such engagement is Chhachhi’s public art project Bhogi Rogi (‘Consumption/Disease’, 2010) (Figure 13), a site-specific interactive installation located in a popular South Delhi shopping mall. The artist used a performance method and tried to keep the work as low-tech and low-cost as possible. The work took the form of a room with a two-way screen at one end. Curious members of the public entered that space, and images of them were superimposed via a camera onto images relating to the work’s theme (the overproduction and excesses of capitalism) that were already projected onto the screen. Thus enmeshed, the two sets of images continually transformed into new visuals. As Chhacchi remarked in a 2000 interview that the interactive technology allows the viewer to play with the images and engage with the concept. Each viewer/performer generated a brief, spontaneous relationship with the pre-projected images, enabling the work to further develop; and the work was completed only when the last participant had exited the room.

Site-specificity is a central aspect of WALA’s performance-based interactive engagements. I focus here on their public performance Kachra Seth Observatory (2010). (Figure 14) The Hindustani word kachra translates as “trash, garbage, filth, detritus”. It has particular metaphorical resonance, since Indian society is rigidly stratified from top to bottom through millennia-old, complex caste hierarchies. Combined with brutal class discrimination, this ensures that the disenfranchised lower strata are thoroughly objectified by the privileged upper strata, viewed and treated as less worthy, less valuable, less desirable in every way (i.e., viewed and treated as no more than human kachra). Seth, a traditional formal title, generally means a rich upper-class businessman, but is also used casually or ironically as a familiar term of address. These two antithetical descriptors were melded into “Kachra Seth,” a fictional character who, as part of WALA’s projects in urban public space, appeared and vanished in different guises in different parts of the city, performing different selves and personae and simultaneously serving as a repository for audience reactions. Kachra Seth Observatory was performed in the lanes of a ragpickers’ settlement in Seemapuri, on the East Delhi border with Ghaziabad district of the neighboring state. The WALA studio was located here; the artists were familiar with the area, spent much time there and had a deep informal daily relationship with the inhabitants. WALA artist Sujit Das created a dramatic disruption at the site via a performative walk in the robes of a Mughal emperor, drawing a range of responses from onlookers. Here the practitioners did not orchestrate the event according a pre-planned template, but instead followed a methodology of responding to whatever spontaneously unfolded at the site during the performance, letting the act take new form from moment to moment.

The Creation of a New Viewership

In India, apart from the people related to the art profession and the typical upper-class art world, visitors from other backgrounds rarely visit the art spaces. So the viewership is limited to this particular class of audiences. However, sets of viewers and new configurations of viewership from different class were provided access through the varying methodologies applied in the art projects like Mashq (Atul Bhalla), Bhogi/Rogi (Sheba Chhachhi) and Kachra Seth Observatory (WALA) undertaken in diverse urban public spaces. Mashq (2006) (Figure 15), a series of still photographs and a video recording, was featured in the final exhibition shown on the terrace of the Al Noor Hotel as a part of closing event of the Dilli Dur Ast residency. Along with the city’s arts community, the local public was invited to the exhibition; many residents and their families visited the exhibition, a very unusual event in a community unfamiliar with the concepts and aesthetics of contemporary art. However, since they strictly observe halal they were able to directly connect with Mashq. Some male viewers initiated a discussion with Bhalla, commenting that he was obviously untrained in the rite. They pointed out his mistakes: for instance, he was not holding the knife correctly, and that the exhibited images did not show blood, an essential aspect of ritual slaughter.

Bhogi/Rogi (2010) (Figure 16), an interactive video installation set in a popular South Delhi shopping mall, was designed to create public awareness around the relationship between health, commodification, consumerism and global consumption of genetically modified foods. Interactive technology enabled viewers to play with and manipulate images–their own figures superimposed on a screen began distorting, shrinking, filling up with food processed from GM crops, demonstrating that our bodies are literally one with what we eat, including foods considered bio-ethically and agriculturally suspect. About 10,000 visitors to the mall participated in this installation, and in a sense were participants of the virtual dimension of the work. This aligns with critical observations that participatory art/SEA articulates the desire to activate the viewers and simultaneously put into motion a drive to involve passersby. Bhogi/Rogi successfully invited the public, who were earlier not familiar with contemporary art, public art or installation art, to experience the idea of economic coercion and environmental damage.

WALA’s performance Kachra Seth’s Observatory—located in a ragpickers’ settlement on the Delhi-Ghaziabad border at the eastern edge of the city—created a stir among the residents at the particular site as well as casual onlookers and passersby. As Kachra Seth slowly and silently navigated the garbage-strewn streets, large numbers of intrigued, bemused people began following him and a festive mood began to build at the site. WALA intended to purposively create a sudden and radical public disruption, relying purely on visual spectacle, and without offering the public a chance to converse with the artists. Rather, they focused on observing reactions provoked by Kachra Seth: the suspense, mystification, bemusement and wonder. The mute figure was so jarring that after a while some youngsters began poking the performer, goading him to speak. Soon the unease translated into overt aggression as the crowd pulled at the actor’s arms and accessories. Finally, he had to be rescued, thus ending the performance. WALA invited a reactive situation created by the unpredictable behavior of the people in the particular site, and they silently observed the viewers’ behaviors until it was acceptable.

3. The Politics of Social Space

Shilpa Phadke argued that “the term ‘social space’ is a production of complex construction and environment determined by the sociopolitical process, cultural norms and institutional arrangements which evoke different ways of being, belonging, and inhabiting.” [36] In India one must continuously consider the complexities of social spaces that reinforce the absolute co-existence and interdependence of different classes within the socio-economic structure. Universally, different classes of people use social space differently, and social spaces, both private and public, are hierarchically ordered through various exclusions and inclusions. [37] In India, unlike the middle, upper-middle and upper classes, the lower-middle and working classes spend a much larger proportion of their time on the streets, rely on street networks, resources and groupings, and use public transport and other public systems to a much greater extent than the privileged strata.

Agarwal and Bhalla focus on the Yamuna riverbank, a public space and also an existent natural space that, for decades, has been under continuous pressure from “development” policies and powerful real estate lobbies, and is now appallingly degraded through destructive usage and government apathy towards such destruction. The devasted action includes deliberate cleaning of the river bank through state policy to make Delhi a world-class city. In the name of redevelopment, the process of building up lucrative housing and also other entertainment spaces on the river bed, forcibly displaces and relocates the poor people to a distant place away from the city. The Yamuna is a major tributary of the river Ganga, and inhabitants of the densely populated plains of North India depend on these two rivers for domestic and agricultural water supply. Devout Hindus have a profound symbolic relationship with the river, since both the Ganga and the Yamuna are goddesses in Indian classical mythology, and have been worshipped for millennia, and are part of Hindu collective consciousness in both life and death–after cremation, the ashes of the deceased are ritually immersed in the waters of these and other sacred Indian rivers. However, the Ganga and Yamuna, while literally nourishing an enormous catchment area, are also among the most polluted rivers in the world. Despite the ongoing destruction of these rivers and various inept government initiatives to “save” them, their banks and floodplains continue to serve as a cultural node and repository for millions of people, and are an invaluable source of livelihood for diverse local communities. [38]

Agarwal has had a long relationship with the Yamuna from his youth onwards, visiting the riverbank many times year after year, first as a bird-watcher and environmental activist, and then as an artist. He describes his attraction to the river as indefinable, constant and powerful, occupying not just his mind but his entire being. Such immersion and internalization, and extensive time spent at the river, enabled him to think deeply about visuality and aesthetics in relation to that particular terrain, and influenced his river-based series of photographic works, films, installations and ongoing engagements that began in 2004 (Figure 18). In terms of his process, with the river, as with any other chosen site, he does not know and cannot predict his responses. Initially, he had no intention to impose an agenda. However, after visiting that particular space for months, he began to get involved with the space politics that is the degradation of the river, which occured through the disposal of waste and the condition of the people living on the bank.

His project in coastal Tamil Nadu (Figure 19), emerged from his interest in the fishing communities being impacted by state policies regarding their livelihood, conservation and coastal “development.” He also drew on the community’s complex relationship to the ocean. These Agarwal projects are developed on-site, as well as both coastal and river projects. The intention is not only to explore the idea of water separately but also to explore the human aspect and political and social hierarchies of the particular space. Later, Agarwal exhibits the project photographs, video installations, and diary notes in galleries and museums.

Sheba Chhachhi and WALA situate their environmental projects in built and crowded urban public spaces. Chhachhi had earlier explored non-traditional exhibition sites, such as the spaces of bastis (densely inhabited slums), for her feminist artwork. Her interest in depicting social power relationships finds expression in her engaged art work. As discussed earlier, her installation Bhogi/Rogi (2010) was set in a lively, popular up-market South Delhi shopping mall, signifying that such spaces epitomize the heart of urban consumption–of food, of luxury items, of all kinds of commodities that comprise the glittering seductions of the global retail economy. WALA situates their art practice in Delhi’s peri-urban working-class localities tightly packed on the land around the city. Over the years, hundreds of outlying villages were gradually and irrevocably reshaped as the city expanded to accommodate millions of economic migrants from neighboring states, rural areas and small towns in other parts of India.

Conclusion

Drawing on my observations of the 48°C public art festival and the four projects discussed in this essay, I have traced how the aforementioned practitioners conceptualized or visualized their work beyond the purview of conventional studios and institutional spaces, and were able to successfully realize their work in social spaces such as streets, parks, riverbanks, quasi-institutional spaces, public libraries, historical monuments, hotels as well as shopping malls through diverse methodologies.

The large-scale transient sculptures, installations and video projections of 48°C, presented in the capital’s public spaces, were fabricated in different locations and then installed at specific festival sites as per the curator and artists’ plan. This first-of-its-kind public art exhibition harbored the potential to attract, through spectacle, a heterogeneous audience/group of viewers hitherto unfamiliar with contemporary art. According to the report on the 48°C Public Art Festival on art ecology, Delhi Green, the official Outreach Organization that coordinated all kinds of activities for the Public Art Festival, is very optimistic about the day’s festival as they mentioned that “the festival was an experiment aimed at interrogating the teetering ecology of the city through the prism of contemporary art.” [39] It has created a significant impact by organizing workshops on global warming, talks and city tours in different installation sites, engaging young artists, art students from schools, and NGOs that run these groups to make them aware of the coming global crisis. The report says that the event saw a good participation by the invited groups. 48°C got massive media coverage, and foreign delegates were present as were the volunteers of the Delhi Green.

While participatory projects such as Navjot Altaf’s Barakhamba Road facilitated a dialogue with the public, CAMP’s Motornama Roshanara trained rickshaw pullers to instruct the strategy of operation in their locality. WALA directly interposed themselves into the city’s marginalized settlements through performance.

Ravi Agarwal, Sheba Chhachhi and Atul Bhalla have a consistent presence as artists in public space. They have built relationships with certain marginalized communities in certain marginalized spaces, and through these relationships are able to harvest material for their artworks. Nonetheless, the final artworks are often taken back to conventional institutional art spaces for purposes of formal exhibition. As a result, the overall conceptualization or execution process remains the artist’s singular prerogative in the projects by Agarwal, Chhachhi and Bhalla. Members of the communities these artists engage with do not actively participate in the process of artmaking or its execution. Most of these artworks have not evolved through collaboration or a dialogic process that involves the resident community of the site. Some works of Bhalla and Chhachhi mark an exception as they have, on occasion, created and installed their works on-site and invited local communities to participate in the public event.

The works included in the festival or the independent projects of the artists discussed in this essay certainly advance the frontiers of the field by making art accessible to an uninitiated public. These works conceptualized explicitly for the public space, offer a platform for spontaneous interaction and dialogue with non-art world audiences. In contrast, the three projects discussed in the next phase in the winter issue directly pitch within the Socially Engaged Art category, with the practitioners primarily using collaborative and dialogic methods in their work with disenfranchized communities to recreate and reclaim these communities’ existent social and public spaces.

Sreejata Roy is a Delhi based artist and academic who has completed her practice-led PhD from the University of Technology, Sydney, Australia (2024) and practice-based Mphil in Media Art from Coventry School of Art and Design, Coventry University, UK in 2005. As an artist interested in community-related projects, Sreejata has been using classical/conventional and mixed and digital media to produce various art forms, engaging the community. Roy’s current art practice in Delhi (2007-present) involves working with young women for over a decade through Socially Engaged Art practice connecting the ideas of public spaces in many sprawling and congested marginalized colonies inhabited by generations of migrants from the neighbouring rural territory.

Roy was awarded a Public Art grant from the Foundation of Indian Contemporary Art (FICA) in 2008 and completed reshaping a community park in one of those marginalized neighborhoods. The project is part of the Public Art Archive published by International Public Art (IAPA). Apart from FICA, she has been awarded other prestigious scholarships in India, including a National Scholarship, from the Ministry of Defence, New Delhi, 1993, Pro Helvetia Swiss Cultural Scholarship to work in Basel, in 2011, IASPIS, the Swedish Arts Grants, Committee’s International Programme for Visual Artists, Malmo, Sweden in 2017, Prince Klaus, Netherland Fund to develop a community kitchen with the migrant, refugee communities in low- income locality in Delhi.

At present, she is an Adjunct faculty in the postgraduate course in the area of Public Art, Socially Engaged Art in the Visual Art Department of Creative Expression at Ambedkar University, Delhi and in Visual Art Department, Ashoka University, Sonepat, Haryana. Roy is a part of Revue; an artist collective based in Delhi (2008-present), and has collaborated on various community and public art projects in India and abroad for several years. Her scholarly papers are published in many significant academic journals.

Notes

[1] Pooja Sood is a curator, arts management consultant and director of Khoj International Artist’s Association, an autonomous artist-led cultural initiative [ https://khojworkshop.org/ ]. Ravi Agarwal is a Delhi-based photographer and interdisciplinary artist, environmental activist, writer, curator and founder of the environmental NGO Toxics Link [ https://www.raviagarwal.com/ ; https://www.toxicslink.org/].

[2] Sheba Chhachhi is a Delhi-based photographer/interdisciplinary artist, documentary filmmaker and gender rights activist. Atul Bhalla is a Delhi-based interdisciplinary conceptual artist focusing on environmental issues [ http://www.atulbhalla.com/ ].

WALA (Akansha Rastogi, Sujit Das, Paribartana Mohanty) are a Delhi-based artist collective focusing on community art and performance art in public spaces. The name derives from the Hindustani word wala a gendered suffix attached to manual professions and vending, e.g., kabadiwala (recycler), chaiwala (tea seller). Wala refers to men; wali to women [ https://walacollective.wordpress.com/about/ ].

[3] See: https://www.hamdasti.com/

[4] My arguments in this chapter are broadly based on the selected interviewees’ responses to the following questions:

- How do you understand site-specificity through your work?

- What is the relationship between the artwork and its public placement?

- How do your art interventions motivate and mobilize people, particularly women, from different backgrounds, around the site of the artwork?

- How do you create new audiences through your practice?

[5] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000), p. 365.

[6] Geeta Kapur, “Secular Artist, Citizen Artist,” Articulation Resistance, Art and Activism. Edited by Achar Deeptha, and Shivaji K Panikkar (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2012), p. 28.

[7] Geeta Kapur, “Secular Artist, Citizen Artist,” Articulation Resistance, Art and Activism. Edited by Achar Deeptha, and Shivaji K Panikkar (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2012), p. 27.

[8] Claire Bishop, Participation, Documents of Contemporary Art (London: MIT Press, White Chapel Gallery, 2006), p. 11.

[9] Achar Deeptha and Shivaji K Panikkar, Articulation, Resistance, Art and Activism (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2012), p. 32-33.

[10] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000).

[11] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000).

[12] Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (India: Tulika, 2000), p. 405.

[13] See: https://khojworkshop.org

[14] See: http://www.sarai.net

[15] The Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA) is a non-profit organisation that aims to broaden the audience for contemporary Indian art, enhance opportunities for artists, and establish a continuous dialogue between the arts and the public through education and active participation in public art projects and funding. See: https://ficart.org

[16] CAMP was founded in November 2007 by Shaina Anand, Sanjay Bhangar and Ashok Sukumaran. CAMP is not an “artists collective” but rather a studio, in which ideas and energies gather and become interests and forms. See: https://studio.camp

[17] Cybermohalla is a network of dispersed labs for experimentation and exploration among young working class people in different neighbourhoods of the city, that was initiated by Ankur: Society for Alternatives in Education, Delhi and Sarai-CSDS, Delhi in the year 2001. Over the years, the collective produced a wide range of materials, practices, works and structures. Cybermohalla generated regular materials including books, broadsheets, installations, radio programmes, and writings about the city. See: https://sarai.net/projects/cybermohalla

[18] For more than three decades, Ankur has been working in the field of experimental pedagogy, with children, young people, and communities in marginalized neighbourhood of Delhi. Ankur seeks to empower the marginalized, through education, to reflect on their life experiences and contexts, and strive for a life of dignity. See: https://ankureducation.net

[19] 1Shantiroad, Bengaluru is an art space founded by Suresh Jayaram that nurtures creativity and cutting edge art practice situated in the centre of the city. See: http://1shanthiroad.com

[20] IFA is an independent, nationwide, not-for-profit, organization that makes grants and implements projects across practice, research and education in the arts and culture in India. Set up as a Public Charitable Trust in 1993, IFA started making grants and implementing projects in 1995. See: https://indiaifa.org

[21] Art room utilizes the medium of art to empower children and women of marginalized communities. The initiative believes that exploring, expressing and exchanging ideas through art creates confidence and stimulates personal growth. Art room promotes a unique and fun community participatory approach, which enables the community to take control over their lives. See: https://artroom.mystrikingly.com

[22] The Mohila Parikh Centre in Mumbai was founded in 1990 and it is an internationally renowned institution and one of the leading centres in India devoted to art and culture. See: https://www.mohileparikhcenter.org/

[23] Artreach is one of India’s foremost arts education non-profits established in Delhi in 2015. They empower participants through creativity and offer enriching learning experiences in the visual arts. See: https://www.artreachindia.org/

[24] Serendipity Arts Foundation is an organization that facilitates pluralistic cultural expressions, sparking conversations around the arts across the South Asian region. See: https://serendipityarts.org/.

[25] The river Yamuna flows through the city of Delhi and its banks are an abode for the thousands of migrant workers from the small towns and villages of the different provinces of India. Unlike many other rivers in the country, the social space on the bank of Yamuna is made up of many settlements, which bunch around it, primarily illegal. Over time these settlements have also suffered the pain of demolition under the name of beautification and urban reformation. However, despite so much violence under the state rubric, life on the riverbank is always thriving. There is an unusual kind of energy pulsating there. The city connects the river through its routine activity of everyday life, both culturally and ritualistically. See: Amita Baviskar, “Demolishing Delhi: World Class City in the Making,” Mute 2, no. 3 (2006).

[26] There is an ongoing Supreme Court case on their licensing, the culmination of a long period of litigation), police brutality and resistance from resident associations, their numbers in the city have grown from about 20,000 in the early 1980’s to more than 90,000today. The vast majority of pullers live on the street, or in” informal” situations in front of shuttered shops, in side-lanes, etc. Recently, cycle-rickshaws have found favour with green groups and the co-lobby, as a “non-polluting” form of transport. This discourse largely does not include considerations of whether Rickshaw wallas will live, their health and other needs, etc. CAMP: Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran 2008. See: https://studio.camp/projects/motornama/

[27] See: https://studio.camp/projects/motornama/

[28] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another, Site-specific Art and Locational Identity (London: MIT Press, 2002), p.11.

[29] Claire Bishop, Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: MIT Press, White Chapel Gallery, 2006), p. 12.

[30] Grant H. Kester, Conversation Pieces, Community And Communication in Modern Art (Berkley: University of California Press, 2013), p.125.

[31] Grant H. Kester, Conversation Pieces, Community And Communication in Modern Art (Berkley: University of California Press, 2013), p. XX.

[32] Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells, Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship(London:Verso 2012), p.26

[33] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another, Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (London: MIT Press, 2002), p.11.

[34] The Farsi proverb dilli dur ast (‘Delhi is distant’), in its full form is hanooz dilli dur ast (‘Delhi is still distant’). The saying, today used colloquially to imply that it may take a long time to achieve a goal, is attributed to the revered Sufi saint of the Chishti order, Khwaja Nizamuddin Auliya (1238-1325), whose tomb in South Delhi has been a major pilgrimage site for centuries.

[35] Claire Bishop, Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: MIT Press, White Chapel Gallery, 2006).

[36] Phadke Shilpa, “Gendered Usage of Public Spaces; A Case Study of Mumbai,” The Fear that Stalks: Gender based Violence in Public Spaces, edited by Sara Pilot And Lora Prabhu (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2012), p. 53.

[37] Phadke Shilpa, “Gendered Usage of Public Spaces; A Case Study of Mumbai,” The Fear that Stalks: Gender based Violence in Public Spaces, edited by Sara Pilot And Lora Prabhu (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2012), p. 53.

[38] With the advent of the neoliberal economy, the Yamuna River became the lucrative space for redevelopment that were settled in and inhabited by squatters. The lands that the urban poor could live on forcibly incorporated into the profit economy and fulfilled the aspiration of a world class city, 100,000 people were forcibly relocated to another part of Delhi by cleaning up the banks. The freshwater that was taken out for drinking water was replaced with untreated sewage and industrial discharge, leaving the river full of filth, a sluggish stream of dirt for most of the year (Baviskar 2006,12).

[39] See: https://delhigreens.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/volunteer-manager-feedback.pdf