“Patriarchal Oil No-More”: Collaborative Memorials of an Oil Spill Clean Up in Galicia, Spain.

Paloma Checa-Gismero

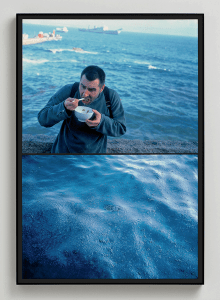

Look down on a white fine sand beach. On the upper left corner of your vision field, curvy rocks softly pop up from the still ocean. It’s a low tide morning and the water, which had receded, moves timidly in. Towards you, from the beach, grow tall green grasses that dance in the cold winter breeze. You are standing on top of a dune, between a lush green forest and the wide-open ocean. The bliss is interrupted by a mass of dark little circles over white, shiny bodies, midway between you and the ocean. Busy, they move heavily, in pairs. It’s hard to see precisely how many there are, as their plastic bodysuits blend in the distance with the morning sun, reflecting on the water. They have been working since dusk, filling a large array of bulky, waist-high, slick black containers that gather in the middle of the scene. The bodies are cleaning the beach.

The scene I describe is from a photograph[1] taken by U.S. artist Allan Sekula in late December 2002. A few weeks earlier, on Wednesday, November 13th, 2002, a violent North Atlantic storm had sunk the oil tanker MV Prestige across the Galician coast in Northwest Spain. Through the following weeks the ship would release an estimated 60,000 tons of heavy oil that would reach land, in successive waves, covering over 3,000 km of coastline in Spain, Portugal, and France. Residents in the region called the tar “chapapote”. The bodies photographed at the beach were just forty or fifty of the tens of thousands of volunteers who traveled from all across Spain and other countries in the European Union to help clean up the mess. The black glossy containers piled up at the beach held the thick oil that volunteers removed from water, sand, and rocks with repurposed fishing equipment, their gloved hands, and shovels.

Despite the magnitude of the spill, the governmental response was slow to come. Delayed by weeks of misinformation from regional and national elected officials, government inaction was combined with censorship in state-run media of the on-the-ground efforts to counter widespread damage of the Galician coast. High ranking officials in the Spanish government misrepresented the crude as “tiny play-doh fingers splitting from the ship” and “oil cookies” sparsely reaching the coast here and there.[2] Instead of sheltering the tanker in a coastal ría—the local name for the region’s wide river mouths—government officials forced its relocation far away into international waters where, battered by strong Atlantic tides and storms, it suffered the uncontrolled release of its load. In addition to Sekula’s photographs, over the next months and years Galician cultural actors would organize a rich and diverse response to the oil spill and its aftermath. Theater plays, protests, performances, quilts, card decks, songs, human chains, costumes, novels, and archives brought different regional stakeholders together under a shared, socially engaged artistic vision.

What Can Art Do

In recent years art history and kindred humanistic disciplines have sought to incorporate the unfolding environmental catastrophe in their analytical purview. The environmental humanities incorporate a variety of methodologies historically developed to study humans as social and cultural actors, with the goal of casting an analytical lens at their embeddedness in nature. As a result, they not only move away from their object-centered nature, but they often challenge, in the process, the foundational culture-nature dualism. Within this turn, petroculture studies seek to disentangle the ways in which dominant forms of energy production deeply impact cultural production.[3] In so doing, humanistic theory has the potential to help relativize, re-write, and reorient dominant narratives that throughout capitalist history have helped naturalize our presumed unescapable dependency on oil to fuel social life. These questions matter both within and beyond the narrow niches of cultural and humanistic production. Within literary studies, Graeme MacDonald has detailed the ways in which fiction can operate as a space in which to not only rethink topical portrayals of oil but, most importantly, as a realm where we can envision representational logics that evade what he identifies as the extractivist, teleological impetus of the novel’s “narrative energetics”. MacDonald characterizes this logic as both inherent to the novel as paradigmatic modern fiction form and to world capitalism as the system in which it came to be.[4] A comparable move is proposed by art historian Caroline A. Jones. In her critique of what she calls the “anthropogenic image-bind,” Jones acknowledges that dominant representational forms within modern and contemporary art conceal an implicit entanglement with capitalist extraction and combustion. She argues that “modernist aesthetics of anthropogenic atmospheres propelled a sensitive subject then canonized in art history. In the process, we cloaked –as aesthetic– our insanely extractive relations to earth”.[5] Ultimately, for Jones, the preponderance of a reception aesthetics in modern art history favored extractive dispositions vis-à-vis our surroundings. I find MacDonald’s and Jones’s propositions fruitful departure points from which to consider contemporary artistic production, in its themes, methods, and forms, within the current escalation of oil extraction and consumption.

This essay considers a variety of artistic approaches to oil and its impact on the environments that humans participate in. Far from classifying and evaluating art forms as more or less appropriate in the unfolding catastrophe, my hope here is to show how a multiplicity of art practices can constitute a choral ecocritical consciousness through which to document and denounce crisis, transform commonsensical narratives about our relationship to oil extraction, and nourish the social fabric permanently eroded by what Nancy Fraser calls “cannibal capitalism”.[6] A feminist critic and historian of capitalism, Fraser proposes a framework that centers social reproduction in her dissection of capitalism’s inherent dependency on fossil fuel combustion. The eco-social nexus, identified by Fraser and the many artists responding to the oil-spill claim, is at the center of today’s systemic crisis. Healing nature is undivorceable from healing the social.[7] Thus, what can art do in the current capitalist crisis? I approach this writing from a place of openness about art’s agency in the unfolding crisis, an openness to multi-strategic action that art historian and activist Lucy R. Lippard outlines as follows:

Art can offer visual jolts and subtle nudges to conventional knowledge. At best it can lead us to look, to see, to understand, and then to act. Artists can also deconstruct the ways we’re manipulated by the powers that be and help open our eyes to what we have to do to resist and survive. […] Among artists’ most important and optimistic tasks is to work with individuals and organizations to restore and remediate wounded nature.[8]

Documenting an Oil Spill

The image opening this essay was just one of the hundreds taken by documentary photographer Allan Sekula, who traveled to the region just a few weeks after the spill. Sekula had received a commission from Barcelona-based journal La Vanguardia to document the catastrophe–the resulting reportage was published on February 12th, 2003.[9] In addition to this printed reportage, a selection of the images would later inform the series Black Tide/Marea Negra (2002), which has been widely exhibited throughout the world since. Although this was his first time in Galicia, Sekula was not new to Northern Spain’s maritime culture. He had photographed Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim Museum several times before, which he perceived as another shoreline example of global capitalism’s aesthetic meddling with the ocean and labor.[10]

Arriving in Galicia, Sekula was struck by the spill’s damage to the coastal landscape. He described the smell as “[a] double stench: fuel oil and rotting organisms of the sea. The alpha and omega of hydrocarbon economy”[11]. His archive from those weeks contains multiple shots of rocks covered with oil, contaminated coastal forests, and inland basins used as receptacles for the removed material. In his notebook, the phrase “birds made featherless, eyeless, fatalized by the oil”[12] show his dismay over the spill’s damage to endemic fauna. But a fine analyst of labor forms in global capitalism, the artist was soon drawn too into the relations established amongst clean up volunteer workers. His photographic archive centers human chains passing along buckets filled with thick oil; pairs of volunteers, their white suits stained black, in synch shoveling a cove; small groups kneeling down on the beach removing oil with their gloved hands; one man pouring water from a bottle into his team mate’s mouth; someone helping someone remove their suit after a long day of work–and many more instances of volunteer cooperation.

In addition to documenting clean up labor organization, Sekula interrogated the subjective experience of volunteers, many of whom were not originally from the region, but had traveled in response to calls for aid, bonding in Galicia through camaraderie built around tragedy. On page 13 of his notebook Sekula describes a Christmas Eve dinner scene among volunteers in the hard-hit town of Muxia:

Volunteers, a slightly smaller Army group: sitting at separate tables, separated by an empty table. Clowning in each group, only a little together. Army ignores music, volunteers clap enthusiastically with the rhythm.

His photographs reflect these behaviors. See, for instance, another image in the album. A group of seventeen volunteers, all in white bodysuits, painstakingly remove the thick sticky oil mass from a beach. Behind them, is a dune covered in green grass and, behind the dune, two old stone houses of a fisherman town. The approximately fifteen-meter-long oil mass was brought to the sand by the high tide, now retreated. It resembles a large-scale paint drip on an abstract expressionist canvas, volunteers un-painting the splatter. Between the group, the heavy-fuel oil mass, and the photographer, walks a young woman, slowly crossing the image left to right. Dressed like everyone else in protective gear, her hair tight in a bun, mouth and nose covered with a mask. Hands clasped at her back, head low, gaze lost.

Sekula’s documentation of the Prestige catastrophe resides somewhere between the instrumental realism and the sentimental realism that he identified as the modes of documentary photography early in his career.[13] The images describe relations of production while simultaneously allowing us to enter the inner worlds of laborers, rendering laboring structures human. But these documents serve, too, as evidence to counter global elites’ desires to render the ocean aesthetically, as a realm for seamless interconnectedness in global capitalism. Neoliberal global trade chains are rooted in localized production, Sekula seems to point out. The ocean, he documents, is concrete and situated, a site of capitalist extractivism and human labor.[14]

Sekula was deeply impacted by the gravity of the situation. In his travel notebook he wrote down fragments of a conversation with local residents: “fisherman in front of Casa do Mar bar: “’There won’t be any fresh fish for twenty years,’ gas station attendant ‘This will last for thirty years’.”[15] He noted the contrast between the lackluster government response to the spill and civil society’s mobilization. On page 7 he wrote “society organized itself against the state” and “popular self-organization in the face of bureaucratic incompetence”; on page 8 he records that “numbers of volunteers swell on the weekend” and listed numbers of demonstrators: “250,000 in Santiago (the Galician capital), 150,000 in Vigo, 70,000 in Pontevedra”. This disconnect between the state’s response and that of grassroots organizers kept growing, as government officials declined responsibility and sought to make the ship’s owner and its insurer accountable for remediation work. Ultimately, bribes and favors to local business leaders distributed by the political party holding the national government (Partido Popular) through its regional and local networks would help silence the growing discontent. But, importantly, the high numbers of demonstrators and volunteers show the magnanimous agency that organized collaboration begets and its power to counter systemic inefficiency.

Protesting Government Inaction

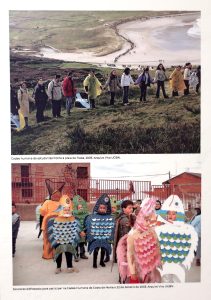

Seven days after the news about the spill broke out, on November 19th, 2002, an ad hoc civil society alliance formed under the name of Nunca Mais (Never Again). The platform became the main organizer of protests against government inaction as well as of efforts to educate the broader public. One of the first large-scale actions they convened is still remembered as the “Umbrella protest”. On December 1st, 2002, over 200,000 demonstrators filled the Obradoiro square in Santiago de Compostela, the Galician regional capital, under the pouring rain, umbrellas in hand.[16] Their protective, waterproof qualities made umbrellas a domestic equivalent to the gloves, safety glasses, boots, masks, coveralls, vests and full body suits that now filled citizens homes and covered their bodies. The hundreds of densely packed umbrellas layered over the square informing yet another thick black tide, in this case of human bodies in raincoats, who moved and chanted in waves, against the stony still walls of the Galician government headquarters. The demonstrators’ bodies were joined by signs and prompts such as oil-covered dead ‘birds’ hanging from sticks; songs, and musical instruments such as windpipes completed the massive gathering. Many other protests would follow, in Galicia and other parts of Spain, including the Marea Gaiteira (Windpipe Tide), a mass gathering of Galician windpipe players attended by over 20,000 people; and the Velorio do Mar (the Sea’s Funeral), a symbolic wake for the deceased ocean in which participants imbedded handmade crosses in the sand and held a public mourning vigil.

These acts of public protest, by which bodies take to public space to express shared feelings of anger, teach important lessons about the role of aesthetics beyond the visual. In these instances, the joy experienced alongside beauty exceeds the limited scope of vision to highlight the embodied experience of emotions jointly felt together. This is a classical move of pathetic persuasion. Symbolic and narrative elements such as those in the protests appeal to the dormant feelings of individuals, eliciting in them simultaneous feelings that only enhance their proclivity to agree as a group in joint consensual judgement–a judgment that, in this case, is unapologetically political. Artist and scholar Gregory Sholette refers to these forms of art activism as “event-objects”. For Sholette, the strongest asset of these event-objects is their power to detach participants from everyday constraints and enter, together, a shared felt awareness of their condition. In his view, event-objects are liberated from the archival imperative; they exist simultaneously in specific form, here and now, and in times, scenarios, and mediums yet to be determined. “Like some vibrant ante-archival agency this version of direct art action interrupts the present by drawing upon its own impending futurity,” says Sholette, pointing to the many other variations that a protest, in its performative or object-based manifestations, will be translated into if successful[17]. Later sections of this chapter describe the many afterlives of these initial acts of protest, in the region and, ultimately, within the national art canon, after their acquisition by the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía in Madrid.

These manifestations helped open a political opportunity window for the Nunca Mais movement. Social movement scholars Susana Aguilar and Ana Ballesteros-Pena attribute its successful call to action in 2002 to the combination of widespread shock caused in the public by the sheer scale of the environmental and economic crisis, and to the presence, in Galician civil society, of robust social networks and professional associations that propelled the movement within the region, helping it gain traction on the national and European stage.[18] In strict social movement theory terms the movement was not successful, as it didn’t directly provoke any changes at the level of government, and none of its calls for infrastructure remediation to prevent future catastrophes were met.[19] However, its legacies can help us understand the role that art production played in the immediate response to the spill, as well as the long lasting ways in which it has since helped forge political consciousness and galvanized collaborative cultural networks in the region to date–a move that problematizes narrow conceptions of success and extends within its purview to the many on the ground symbolic negotiations that have occurred in its wake.

These public manifestations of dissent, uttered in the public space and, as I will later show, eventually within art institutional spaces, expressed citizens’ anger about the oil spill and the lackluster government response. Their protest was as much against Big Oil as it was about the legal apparatus and economic regime that uphold its hegemony over social and natural life. Nancy Fraser’s concept of “cannibal capitalism” is a helpful tool through which to understand the systemic crisis unfolding before the protesters–and us too, two decades after the spill—in which episodes such as the Prestige catastrophe are just one of its most visibly striking manifestations. Fraser conceives of capitalism as inherently bound to the extraction and burning of fossil fuels. In her view, capitalism cannot be understood outside of this basic relation with nature. However, she is clear to state that this core feature of capitalism is nevertheless always historically articulated, and has taken different forms through its historical stages. In our current, fourth stage of capitalism, that which she calls of the “globalized bads,” the previous ills characterizing capitalism until the late twentieth century coexist in hyperbolic expression. The present stage features elements from (1) mercantile capitalism’s reliance on animal and human labor; (2) the coal-fed industrial revolution of the nineteenth-century; and (3) the rise and protagonism of the fossil fuel industry for most of the twentieth-century.[20] The Prestige spill must be understood in the latest and fourth stage, within a larger global system shaped by neocolonial relations and oceanic trade, in which exosomatic (that is, processes able to generate energy output from combustion) consumption in the Global North further escalates–yet the materialist processes associated with the first, second, and third stages of capitalism are increasingly reallocated to the Global South.

This global capitalism on steroids has important repercussions for life. While on the one hand it depends on this fundamental exosomatic activity, Fraser argues, it is by this very same feature that capitalism erodes the conditions that allow for its existence. Damage derived from exosomatic activities impacts, directly, what we commonsensically call “nature”.[21] Fundamentally, through exosomatic activity capitalism destabilizes ecosystems. But, in addition, its economy depends on the distinction between nature and economy, disavowing the damages it causes. These four D-words are key moments in Fraser’s articulation of capitalism’s internal contradictions and explain our current system’s internal tendency to crisis. Capitalism is cannibalistic, yes, but like the protesters and artists responding with anger to the Prestige oil spill very clearly articulated, capitalism’s cannibalistic drive extends, too, to social reproduction. The extractivist logic inherent to capitalism is not exclusive to the extraction of natural resources, but extends, too, to the extractivism that constitutes labor in neoliberalism–an extractivism that is especially violent in domestic work, convict work, wage-based work, and the different forms of unpaid work that support social life.

In its compulsion to extract profit, neoliberalism ravages the social relations that, Fraser warns, are perceived as “‘non-economic’ [but] make ‘the economy’ possible”.[22] This non-economic realm includes social reproduction activities such as the birth and rearing of new humans, cultivating relations with friends and relatives, and nourishing a strong social fabric. These activities take many forms and are woven into and shaped by our different social habituses. They are tightly imbricated with the production of, and participation in, culture–including, but not limited to art.

At 10PM on December 27th., 2002, Nunca Mais and affiliate organizations called for a massive electricity blackout in Galicia. On January 6th., 2003, over 100,000 people joined in Vigo a ludic protest accompanied by the Reis Magos do Chapapote (the Three Kings of Chapapote). 50,000 elementary, high school, and university students formed a human chain over the cliffs between the hard-hit coastal towns of Laxe and Muxía on January 22, 2003. Smaller human chains would follow throughout the region. Weekly protests occupied central squares in towns and cities. All these events featured two key symbolic through-lines: denunciations of what made the Prestige catastrophe simultaneously natural and social, and a playful inventive use of puppets, costumes, prompts, and visual imagery. In Fraser’s words, “when people fight back, it is often to defend the entire eco-social nexus at a single stroke, as if to defy the authority of capitalism’s divisions”.[23] Protestors were, indeed, keenly aware of these entanglements shaping the eco-social nexus.

Sustaining Life in Crisis

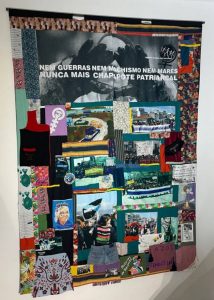

On March 8th, 2003, chants of “¡Nunca mais chapapote patriarcal!” (Never again, patriarchal oil!) and “Nem Guerras, nem machismo nem marés. Nunca máis chapapote patriarcal” (“No to the war, no to machismo, no to tides. Never again patriarchal oil”) reverberated across a massive protest between the coastal towns of Cee and Fisterra. Followed by a caravan of buses, vans, and private cars, thousands of women traveled the roughly 15 km. between both towns in solidarity with those directly affected by the Prestige spill. It was the Marcha Mundial de las Mulheres, the Galician chapter of the International Women’s March. The annual public protest was launched by the Quebec Women’s Federation in Brussels in the year 2000. The international and multiracial feminist movement seeks to denounce the causes of poverty and violence that affect women worldwide. The two central chants articulated the protesters’ perceived entanglement between patriarchy and Big Oil in their everyday lives. Both were sources of systemic violence, they claimed, and, together, these two forces conditioned women’s economic and social disadvantages. Importantly, the 2003 Marcha de las Mulheres coincided with a massive wave of protests throughout the country against Spain’s participation in the Iraq War. Two million protesters in Madrid and 1.5 million in Barcelona took to the streets singing “¡No a la guerra!” (“No to War!”). Overall, an estimated 11 million protested nationally against the Government’s decision to join the United States and the United Kingdom in the invasion.[24] The war, protesters claimed, was linked to the United States government’s interest in expanding its oil extraction capacity by securing a stronghold in the Middle East. The slogans, posters, and the many papier-mache prompts protesters carried and wore expressed a shared group and political consciousness among the thousands of regional women who took to the streets.

Activists understood, from the beginning, the importance of preserving a record of their actions. Unha Gran Burla Negra (A Big Black Joke) is one of the organizations working to archive these memories. The non-profit was constituted in 2018 by a group of culture actors, many of them organically affiliated with the original Nunca Mais movement core. Their principal mission is to construct a “live archive” of the Prestige oil spill and its many and diverse aftermaths. Since its constitution, UGBN members pursued two goals: sustaining a unified narrative of the spill and its aftermaths that centers civil society, and creating a live archive with the many related objects produced since the catastrophe. Through the years they have partnered with different organizations, such as activist press Difusora, which committed itself to collecting posters, leaflets, flyers, banners, and the many multimedia objects produced directly following the spill, and the Library at the University of Santiago de Compostela, which is now the main repository of the paper-based elements from this larger collection.

Although UGBN’s collaboration with the University archives has made a small percentage of the primary sources publicly accessible to researchers, UGBN members acknowledge the limitations of institutional archives to record the value of grassroots, para-institutional object-events of this nature. Concerned with the historical links between institutional archives and political power, Maria Bella, an artist and curator member of the collective, has been a leading proponent of the model of a “live archive”. How, she has asked, does one translate the multiform, grassroots, emancipatory nature of the power relations that formed post-Prestige civil responses into the imperatives of public access and historical preservation that guide archival work? How to avoid already consolidated archival forms–such as the city, the university, and the private foundation archive—from coopting the distributed energy, embodied knowledges, and justice-oriented action that informed these events? And last, what archival tools might help preserve, in a publicly accessible manner, the many primary sources that do not fit into traditional archival categories–t-shirts, head pieces, songs, umbrellas, pins, etc.?

Unha Gran Burla Negra confronts these challenges with a multi-pronged approach. Conscious of the long history of effacing situated knowledge that surrounds the acquisition, collection, and display of cultural objects in the traditions of Western modernity, they invited the public to activate items from the collection via strategies that accentuate their performative, relational, and political potential. These activations have taken many forms: theater plays, exhibitions, protests, conversations, card decks, postcards, and quilts. This approach, which they define as “experimental,” allows them to conceive of their archival labor as a labor of care, a humanistic tending to these objects that seeks to nourish the values, affects, and memories that supplement their material dimension. The activations relive the immaterial qualities of these primary sources, reawakening aspects of the post-Prestige years that still haunt area residents, but whose nature is not easily translated into the formalist classifications of institutional archival logic. Their efforts to circumvent the institutional mechanisms invested of official memory–such as the university or the regional city museum—engrain their own version of archival practice into the realm of social reproduction.

Crafting Public Memory

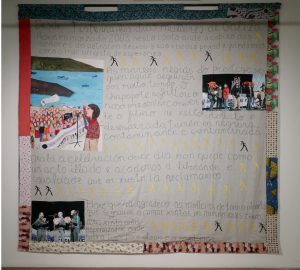

The long-lasting impact of the Prestige heavy-fuel oil spill in the region’s economy explains its prevalence as a topic of concern to contemporary artists. Since 2002 exhibitions of ephemera have circulated through the region, and the event has been addressed by a number of artists, filmmakers, writers, and musicians since. In late 2019, seventeen years after the spill, Bella started efforts to produce a series of collaborative quilts to memorialize the feminist organizing that occurred in response to the spill. The origin of this initiative had been a conversation with Carmen Arnoso, mother of a comrade in the collective, who once shared with Maria her surprise that none of the art interventions related to the Prestige spill had ever centered the role of women during the crisis and thereafter. This was appalling to Carmen, as women had played a crucial role feeding, housing, and transporting clean up volunteers, and had later, in mass, redirected their employment towards the textile and tourism sectors, in efforts to supplement the diminished household incomes from the paralyzed fishing sector. If women had kept everyone alive, why would no one care to acknowledge it?

The social reproductive labor of women during and after the spill was a central claim of the 2003 Marcha Mundial de las Mulheres. In 2019 Maria Bella drew from this legacy in her efforts to sustain the memory of the Prestige catastrophe’s afterlives. Her research, informed by archival work and interviews with participants, led to the creation of an archive of its own that, in turn, took several forms. Its first iteration occurred in 2020. In March of that year, news of a highly contagious virus stopped plans for a women’s’ march in Galicia. Instead, Bella and her collaborators decided to occupy the windows of closed down stores in the town of Viñanzo to display documents of the 2003 Marcha de Mulheres and surrounding actions. Early during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, this exhibition, which turned the empty streets into a repository of documents of community organizing efforts, became a living memorial to the role played by women in sustaining life during the previous crisis. Incorporating photographs and ephemera of the 2003 Marcha de Mulheres invoked the strength of regional feminist networks, in uncanny anticipation of the crisis to come.

Bella’s plans for a series of quilts materialized through the first pandemic year. With strict lockdown regulations in effect in Spain, her initial conception of the project had to be modified in response to the restrictive mobility shaping life during those months. Her initial conception of the process as a month-long series of meetings in which women met to collaboratively sew the quilts, became impractical. Instead, she and a local sewing instructor, launched a call for contributions to participants through a number of Galicia feminist networks. The two would sew together these fragments, provided by individual participants, into the quilts. The first quilt is framed by fragments of six different fabrics: floral patterns, polka dots, and an abstract geometric blue and yellow print. On the left, centrally positioned, a hand painted scene is sewn into the central white field. The scene shows a gathering of women on a port. Three boats fish on a blue ocean behind them, which is framed by two lush green inlets. The women hold a large banner that reads: “Nem Guerra Nem Machismo Nem Mares. Nunca Mais Chapapote Patriarcal” (“No to the war, no to machismo, no to tides. Never again patriarchal oil”). Another woman leads the chants from a stage. She speaks into a mic, which she holds in her hand. Sewn onto the quilt is another scene, this time a photograph printed on fabric, of six women on that same stage. They chant and play drums. Four of them wear seafood-shaped head pieces: a shark, an octopus, and two crabs—the two latter being central products of the local fishing industry, whose harvesting was banned for a year following the 2002 spill. On the bottom left corner of the quilt, another photograph printed on fabric shows three musicians performing on the same stage. Two play pandereta (a traditional hand-held percussion instrument) while the three sing. Embroidered on the quilt’s main field through the three fragments is the declaration that opened the 2003 Marcha da Mulheres between Cee and Fisterra. In between the paragraphs, rows of female figurines dance, resembling paleolithic cave drawings, in yellow and black:

From Fisterra, good morning, women of Galicia,

Today, in March 2003, on this shore where the [cobiza] of the petrol lords left their sticky viscous spill, we face the sea with chants of hope.

The back tides from the Prestige will continue to come [to our shores] for a long time. Chapapote asphalted our present and turned our future into a violent and desperate gesture; also in a blackness that is polluted and pollutant.

Let’s be sure that today’s celebration doesn’t stay as a single [illado] act. Let’s achieve the freedom and equality that we reclaim in justice.

Today I want to thank all the women on this planet. May we continue to make together a more tender world, [a world that brings] more justice and hope, with room for utopia and revolution.

The second quilt adopts a less centralized approach, arranging fragments throughout the whole field. At its top is a reproduction of the original poster announcing the march: a large-scale two-piece photograph of a woman’s face behind her two large hands, in gloves covered with thick oil. Across the image is, again, the Marcha’s motto: “Nem Guerras Nem Machismo Nem Marés. Nunca Mais Chapapote Patriarcal”. Several fragments of printed paintings show a uterus, seashells, and portraits of regional matriarchs. One of them centers on a car caravan that accompanied the 2003 Marcha da Mulheres. A larger number of photographs printed on fabric turn the quilt into a vertical album of the event. The images include women marching from Cee to Fisterre, protesters holding banners, taking the town’s central avenue, details of their head pieces, press clippings, the Prestige, the Nunca Mais movement logo. One of them stands out in the middle of the quilt: a photograph of the central banner carried in the 2003 Marcha da Mulheres. The large square fabric is stained in black, emulating chapapote. In negative, white block letters read “Nunca Mais Vida por Petroleo. 8 de marzo.” (“Never again, life for petrol. 8 March”).

Together, the quilt diptych enlivens the Women’s March memories while reactivating them in the context of another crisis. Since their creation, the two objects have been exhibited in local cultural centers, libraries, and schools. As during the aftermath of the oil spill, life during the Covid-19 crisis foregrounded the importance of care work in sustaining life. Each time they are shown, the quilts are activated through a variety of public-facing activities. They have been objects of conversations on university campuses, they have been exhibited in local culture centers throughout the region and, most recently, they were part of a larger exhibition of contemporary art and ephemera dedicated to the Prestige oil spill. Their audiences are more than often non-art audiences, but neighbors from the region and university students–some but not all having been directly involved with the post-spill remediation efforts. Throughout their many iterations, the exhibitions of the quilts have helped to jumpstart conversations between different stakeholders, not only educating the public about an important moment in recent Galician history, but also facilitating the recognition of others’ lived experience, their emotions, desires, and goals. Importantly, in their itinerance, the quilts help ground discussions about care work and women’s role in it, forms of protest in rural space, and the similarities between labor that tends to nature and labor that tends to human life. In addition to their visual and tactile qualities, they are prompts for dialogical exchanges in which aesthetic value exceeds the sensory to return, again, to the shared experience of togetherness.[25]

Maria Bella has long reflected on the parallels between craft work and the labor of social reproduction. In our conversations she mentions the influence of U.S. quiltmakers Rosie Lee Tomkins and Miriam Shapiro in her conception of the quilts’ formal attributes, particularly their use of diverse colors, their recourse to abstraction and their insertion of hand-embroidered text in their compositions. But Bella also looked to other craft forms traditionally carried out by women in Galicia: net weaving and sewing. Net weavers mend and fix the nets used in rock fishing, shore fishing, and boat fishing in the ocean. This type of work is practiced by women in coastal towns, often as part of the domestic chores performed in the household to support the mostly masculine work of fishing and seafood harvesting. Far from restricted to the domestic sphere, however, sewing informs a large part of the Galician economy. The region has a long history as a center of textile production (including fishing nets), an industry that since the 1980s has been coopted by fashion conglomerate Zara, with headquarters in the region.

The massive protests mirrored the many clean up volunteers photographed by Sekula. Sekula imagined the act of cleaning as a collective labor of Sisyphus. He wrote a script that accompanies the Black Tide series, titled Black Tide: Fragments for an Opera. Its opening renders the act of cleaning as an eternal, cyclical, curse on the xente do mar (the people of the sea).

The Chorus is dressed in white: hooded in waterproof, sweat-retaining Tyvek suits, taped at the cuffs with transparent package tape. They seal each other into their suits, stooping to bite at the tape with their teeth. This preparation is performed with ritual solemnity, in silence. A Fisherman, enters, stage right, and gestures toward the chorus:

“These are the astronauts.”

At first the scene has the look of an airplane crash or a terror-bombing, the carnage viewed from a distance, from behind a barrier of yellow tape. Voices rise with the wind: the swelling mask-muffled dirge of a collective Sisyphus, the chorus trailing across the dark beach in a ragged line, passing unwelcome cargo from hand to hand up the steep slope of the raking stage.[26]

The Prestige oil spill was just the eighth and latest of a series of large scale black tides that have occurred off the Galician coast since the 1950s: Janina (10,000 tons, 1957), Yanxilas (16,000 tons, 1965), Spyros Lemnos (15,000 tons, 1968), Polycomander (15,000 tons, 1970), Urquiola (100,000 tons, 1976), Andros Patria (60,000 tons, 1978), Mar Egeo (67,000 tons, 1992), and Prestige (63,000 tons, 2002). Together, these eight ships spilled on the same shore over 360,000 tons of heavy oil in just five decades. As I finished writing this article, millions of plastic pellets washed up on the same shores, after a container fell to sea from a Liberian cargo ship off the coast of Portugal.[27] Given the long list of repeated catastrophes, we can imagine many volunteers before and after 2002 cleaning the beaches of this well-trodden global maritime route. As we see in volunteers’ faces, and as uttered by the thousands of protesters and artists in the months and years after the spill, beach remediation work often felt hard, futile, and repetitive.

Hardness, futility, and repetitiveness are characteristics of social reproductive labor. In a beach clean-up and in the many other activities that sustain and nourish life, representations of heroic, extractive labor are often absent. Instead, the focus is on what can be accomplished through joint, often backstage, less visible, collaborative action. Clean up volunteers, as well as those, mostly women, mending fishing nets, birthing and raising life/ tending to regional agriculture, and working from home as seamstresses for the regional fashion mogul, perform the behind-the-scenes labor that keeps nature and culture going during periods of crisis. These subdued practices of social reproduction exemplify energy economies that are horizontal, renewable, and sustainable models that do not rely on the extraction of resources, but rather, on their networked transformation.

While they may (initially) seem to have little to do with the history of art, events like the Prestige oil spill have much to contribute to the field. As I’ve presented it here, the event was clearly ripe with imagery. It transformed the landscape of the Galician coast, was documented through a diversity of media, and triggered a wide array of cultural manifestations in varying responses from civil society, then and now. But monumental historical events like this one can also provoke important reflections on the role that art history can play in transforming dominant petro-imaginaries. Together with other approaches to art making, such as the socially committed documentary practice of Allan Sekula, they inform a choral ecocritical consciousness that promises strong strategic agency. Perhaps it is in this direction that we ought to look, when searching for paradigms of cultural production that might escape capitalism’s cannibalistic nature. Perhaps these fluid multimodal alliances could help us escape what Jones calls the “anthropogenic image-bind,” in which dominant aesthetic paradigms finally break free from extractivist dispositions towards our planet.

Paloma Checa-Gismero is Assistant Professor of Art History at Swarthmore College. Her writing about art biennials, craft, and socially engaged art has been published in journals such as Third Text, Afterall, The Journal of Modern Craft, and FIELD. She is the author of Biennial Boom: Making Contemporary Art Global (Durham: Duke University Press, 2024).

Notes

1. I am thankful to Sally Stein and Maria Bella for their generosity facilitating images. ↑

2. “Rajoy en 2002: ‘Del Prestige salen unos pequeños hilitos con aspecto de plastilina’” Libertad Digital. December, 2002. 2’02’’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otIBaCJLdn8 ↑

3. See the important work done by the Petrocultures group. www.petrocultures.com ↑

4. Graeme MacDonald, “Research Note: The Resources of Fiction”, in Reviews in Cultural Theory, 4 (2). pp. 1-24. ↑

5. Caroline A. Jones, “Atmospheres and the Anthropogenic Image-Bind”, in T.J. Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, Subhankar Banerjee, editors, The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (London: Routledge, 2021). pp 242-251 ↑

6. Nancy Fraser, Cannibal Capitalism (London: 2021, Verso) ↑

7. I draw from Fraser’s analysis in two articles later compiled into her book Cannibal Capitalism (London: Verso, 2022). See Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care”, New Left Review, 100 (July-August, 2016), pp. 99-117; Nancy Fraser, “Climates of Capital: For a Trans-Environmental Eco-Socialism”, New Left Review, 127 (Jan-Feb, 2021), pp. 94-127 ↑

8. Lucy R. Lippard, “Describing the Indescribable”, in TJ Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, Subhankar Banerjee, eds., The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (London: Routledge, 2021). pp 47 ↑

9. Allan Sekula, “Black Tide/Marea Negra”, Culturas, La Vanguardia, February 12th, 2003. ↑

10. Allan Sekula, “Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea (Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs)”, October, Vol. 102 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 3-34 ↑

11. Travel journal to Galicia by Alan Sekula, Black Tide, 2002 December 18-2003, box 10, folder 8, Allan Sekula papers, 1960-2013, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no.2016. M.22. pp.11 ↑

12. Travel journal to Galicia by Alan Sekula, Black Tide, 2002 December 18-2003, box 10, folder 8, Allan Sekula papers, 1960-2013, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no.2016. M.22. pp.10 ↑

13. Allan Sekula, “Photography Between Labor and Capital”, in Benjamin H.D. Buchloh and Robert Wilkie, eds., Mining Photographs and Other Pictures 1948-1968 (Halifax: The Press of Nova-Scotia College of Art and Design, 1983). pp. 201 ↑

14. For Sekula’s analysis of the uses of photography to imagine a seamless globalized world, see Allan Sekula, “Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea (Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs)”, October, Vol. 102 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 3-34 ↑

15. Travel journal to Galicia by Alan Sekula, Black Tide, 2002 December 18-2003, box 10, folder 8, Allan Sekula papers, 1960-2013, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no.2016. M.22. pp.11 ↑

16. For scale, Santiago de Compostela’s population in 2002 was 93,273 residents. ↑

17. Gregory Sholette, “Merciless Aesthetic: Activist Art as the Return of Institutional Critique: A Response to Boris Groys,” FIELD, A Journal of Socially Engaged Art Criticism 4 (Spring 2016), http://field-journal.com/issue-4/merciless-aesthetic-activist-art-as-the-return-of-institutional-critique-a-response-to-boris-groys. ↑

18. Susana Aguilar and Ana Ballesteros-Pena, “Debating the Concept of Political Opportunities in Relation to the Galician Social Movement ‘ Nunca Máis ‘”, South European Society and Politics, 9, (3):28-53 ↑

19. They did, however, play an important role in government changes in subsequent years. In words of Galician writer Manuel Rivas: “One great piece of fake news that circulates about the mobilizations that followed the Prestige [spill] is that it didn’t serve for anything politically. But of course it did: two years after there was a change in government in the Xunta [regional government] and in 2004 changed too the [central] government in Madrid”. Marcos Pérez Pena, “20 anos da manifestación dos paraugas: “Ante a catástrofe, en lugar de meterse na cuncha Galicia escolleu protestar”, Praza.gal, December 1st, 2022 https://praza.gal/acontece/20-anos-da-manifestacion-dos-paraugas-ante-a-catastrofe-en-lugar-de-meterse-na-cuncha-galicia-escolleu-protestar ↑

20. Nancy Fraser, Cannibal Capitalism. ↑

21. Nancy Fraser, “Climates of Capital: For a Trans-Environmental Eco-Socialism”, New Left Review, Jan-Feb 2021 (94-127) ↑

22. Nancy Fraser, “Climates of Capital”, p. 100 ↑

23. Nancy Fraser, “Climates of Capital”, p. 105 ↑

24. “Los organizadores cifran en más de tres millones los manifestantes en Madrid y Barcelona”, El Pais, February 15th, 2003, https://elpais.com/internacional/2003/02/15/actualidad/1045263602_850215.html ↑

25. My thinking here is informed by Grant Kester’s concept of dialogical aesthetics. See Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013) ↑

26. Allan Sekula. “Black Tide: Fragments for an Opera”, La Vanguardia Culturas, 3, February 12, 2003. ↑

27. See Sam Jones, “Northern Spain on alert as plastic pellets from cargo spill wash up on beaches”, The Guardian, January 9, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/09/northern-spain-plastic-pellets-cargo-spill-beaches ↑