Listen to the City Contesting Urban Necropolitics Against Disability: The Case of the 2017 Pohang Earthquake in South Korea and Its Aftermath Through the Project No One Left Behind

Jason Waite

If the ontology of the body serves as a point of departure for such a rethinking of responsibility, it is precisely because, in its surface and its depth, the body is a social phenomenon: it is exposed to others, vulnerable by definition. Its very persistence depends upon social conditions and institutions, which means that in order to “be,” in the sense of “persist,” it must rely on what is outside itself. How can responsibility be thought on the basis of this socially ecstatic structure of the body? As something that, by definition, yields to social crafting and force, the body is vulnerable. Judith Butler[1]

On the chilly afternoon of November 17, 2017, a 5.4 magnitude earthquake hit over half a million residents of the eastern seaboard city of Pohang, South Korea. Over one thousand buildings were wrecked, displacing residents, and causing the most damage by an earthquake in Korea since 1905.[2] While there was no loss of life, the event was traumatic for the area and the nation, which was unaccustomed to earthquakes. The earthquake, along with the increase in large-scale climatic events, underscored the need for more comprehensive disaster planning in Korea. Yet not all groups of society have the same needs or abilities in times of crisis, and often urban planners or private developers do not take into account the needs of the most vulnerable in society. As such the Seoul-based artist collective Listen to the City has addressed this planning gap.

Following theorist Robert McRuer’s analysis that, generally, human beings are only temporarily able-bodied, those people who are (temporarily) able-bodied beings must necessarily align themselves with the disability movement, as it is critical toward common survival.[3] The recognition of the importance of the discourse of vulnerability and interdependence comes to the foreground when discussing the large portion of the population that identifies as having a disability. It is even more critical to understand this discourse not as an isolated set of conditions, but rather as a shared experience of all human beings. It can be easy for temporarily able-bodied readers to overlook the infrastructure they traverse— streets, sidewalks, metro stations, building entrances, staircases—as just background urbanity. However instead of facilitating the movement of people, this same infrastructure can become an obstacle or a barrier. This infrastructure created by the state or capital can lack basic care for others, reflected in the inaccessibility of such structures. Whether this be an oversight in planning due to the prejudice of the temporarily able-bodied, a lack of regulation, or a lack of enforcement of existing laws.

To counteract this urban necropolitics, the Seoul-based artist collective Listen to the City has for over a decade been laboring to amplify urban resident voices and perspectives on planning as well as develop the collective’s own artworks and interventions, all of which aid and put into practice an alternative vision for the city. The collective member Park Eunseon terms this type of practice feminist insurgent planning. This article aims to unpack the notion of feminist insurgent planning and how it contests two foundational aspects of urban necropolitics: 1. the framing of how knowledge about the city is produced, thus informing who can be considered an expert; 2. the lack of democratic, inclusive consultation on decision-making in urban planning. The following section examines how Listen to the City employs two key aspects of feminist insurgent planning—situated knowledge and active listening—to disrupt urban necropolitics will be seen through the case study of their film and project No One Left Behind (2018), which focuses on experiences of the disability community during and after the Pohang earthquake in South Korea.

A roadmap to the concept of feminist insurgent planning was laid out by Park in an academic article she published on Listen to the City’s role in contesting the forced displacement and gentrification.[6] In the article, she details how feminist insurgent planning “is a radical urban planning method that seeks alternative solutions to urban problems from the perspective of the periphery through the experiences and participation of citizens.”[7] This bottom-up approach to how communities can and should exist centers two fundamental methods. First, it entails an understanding that knowledge is situated. Hence the communities and neighborhoods already have a wealth of understanding of their own needs and desires, as well as an in-depth knowledge of the ecological and social histories of an area. Framing knowledge as being situated does not ignore the role of experts; instead, it demands that expertise be materially grounded and interoperable with local conditions. Emphasis on the critical role of situated knowledge thus pushes back on abstract uniform planning solutions with no basis or relation to the local ecology. This does not restrict the field of experts but rather widens the understanding of the horizon of knowledge itself and who can have expertise.

Another important component of feminist insurgent planning is active listening, and the act of care and attention to a spectrum of voices—in particular, those who are marginalized. This form of holding oral space is critical to the weaving of bonds that feminist insurgent planning both traces and enacts. Holding this space of active listening can open up worlds of situated knowledge that inform the practice of feminist insurgent planning. We shall see how these forms of situated knowledge and active listening were foundational processes to Listen to the City’s response to the Pohang earthquake and the creation of their project No One Left Behind.

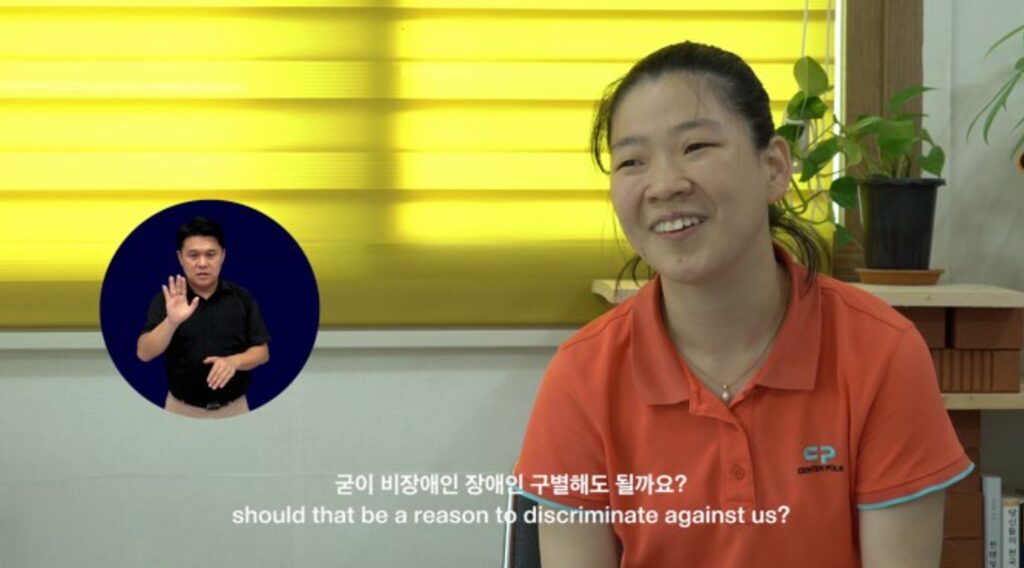

The feminist insurgent planning methodology of Listen to the City propelled them in a unique direction to respond to the 2017 earthquake. The collective undertook interviews with the city’s sizeable disability community to see how some of its most vulnerable residents were affected in this time of crisis. These interviews, which covered their experiences before, during, and after the earthquake, formed the basis of the half-hour film No One Left Behind. The film begins by framing Pohang through the lens of its industrial development in the 1970s via the imposing Pohang Iron and Steel Company (POSCO) that dominates the city’s landscape. This helps to frame the city as a company town whose infrastructure and welfare initiatives were set up by POSCO, a fact underscored in the film by the long shots of the city and neighborhoods that help provide a tangible texture of the characteristics of this company town. This framing of the company town landscape also nods to the “productivist” mentality embedded in the city and the ethos of physical labor that is circumscribed in industrial manufacturing, which immediately helps us to understand this environment where productivity can overshadow the vital work of social reproduction.

After the earthquake, the municipality of Pohang held a series of meetings intended to learn from the disaster and how to develop better preparedness for the next crisis. Listen to the City’s film chronicles how in these town meetings, many people with disabilities showed up to share experiences with the committee and have their voices on record to share how this sizeable portion of the population, people with disabilities, grappled with the earthquake. The residents recalled how they were ignored in the meeting and not allowed to speak, with preference given to testimony by the temporarily able-bodied individuals. This account of not being listened to by officials during town halls underscored the enforced marginality of this group. Even when those residents with disability who went through the effort to engage in the formal arenas of the democratic decision-making process around urban planning were still discriminated against and silenced. This example of exclusion from the process demonstrates urban necropolitics even in a so-called democratic approach to urban planning and disaster management where the privilege of sharing knowledge and experience was exclusive to the temporarily able-bodied. Thus, even after this traumatic event of the earthquake that highlighted the poor municipal disaster planning—where surprisingly no one was killed—by not taking into account their needs again, this urban necropolitics continued to impose the specter of death on the disability community when the next disaster struck.

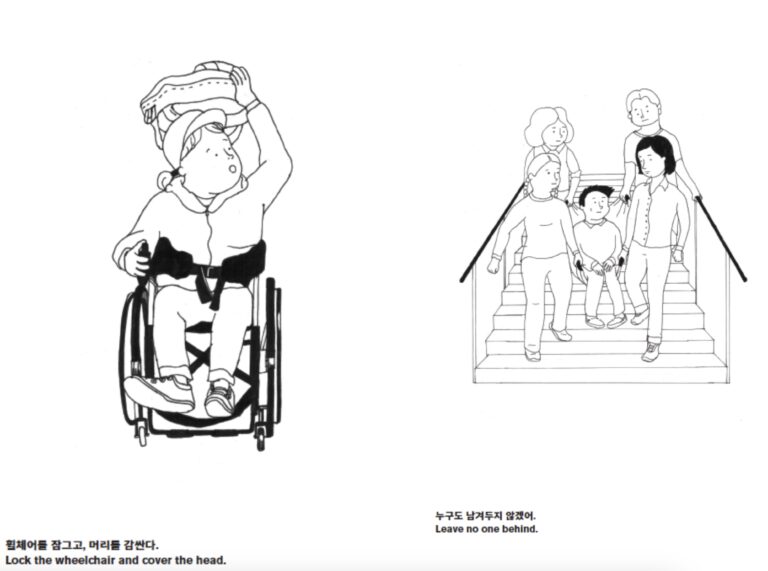

Instead of the municipality, the artist collective Listen to the City worked with the residents to develop the first manual for evacuating persons with disabilities. This manual is a resource not only for the residents but also for the temporarily able-bodied and decision-makers, laying out the type of practices that should be in place. The manual contains illustrations of, for example, how the temporarily able-bodied can help different bodies navigate stairs and assist in evacuation. The manual’s creation to contest the dangerous void left by urban necropolitics highlights the importance of the project of feminist insurgent planning in recognizing the intrinsic situated knowledge of residents and the practice of active listening—critical practices that highlight those on the margins and centers their experience of the city. The fact that artists took a different approach to responding to a disaster by seeking out those most vulnerable to hear their experience and collaborating with them to develop a more inclusive process for future disasters, demonstrates the important role of creative approaches in understanding the urban environment. No One Left Behind and the art practice of Listen to the City demonstrates one of many ways that art and culture provide a critical contribution to society.

Beyond addressing the immediate community in Pohang, the video and manual were shown at the art biennale Seoul Mediacity 2018. These artworks contributed to the discourse of the biennale, focusing on ideals around what consists of a “good life.” Listen to the City’s artworks pushed this discourse beyond who perhaps the organizers had in mind for partaking in their “agora.” In addition, the artworks also reached a broader audience consisting of temporarily able-bodied visitors as well as persons with disabilities. This was critical, as Park explains, “In real life disaster situations persons with disabilities and [temporarily able-bodied] are usually in the same space. Therefore, we must learn how to evacuate together.”[8] Here, the artwork and its public circulation in museums and the press furthers Listen to the City’s project of feminist insurgent planning. Attesting to the tangible impact of the project, outside of reaching a vast number of temporarily able-bodied visitors and persons with disabilities in Seoul, Pohang, and beyond; the National Disaster Management Research Institute in Korea invited Listen to the City to consult on developing a more inclusive disaster management approach in Autumn 2022 and any policy changes have yet occur in 2024. However, as the interviews with the residents in the video and Park’s paper underscore, it is not only in times of crisis that society needs to adapt to the needs of the most vulnerable but more broadly, transformations of our everyday infrastructure can increase the participation in the city and ensure an accessible future for even the temporarily able-bodied beings.

In conclusion, feminist insurgent planning, as demonstrated through the No One Left Behind project, provides a powerful framework for contesting urban necropolitics. By actively listening to marginalized voices, recognizing the situated knowledge of communities, and creating resources for inclusive disaster management, this approach challenges the exclusionary practices that persist in urban planning. It is a call to action for all cities to prioritize the welfare and inclusion of all their residents, ensuring that no one is excluded from the built environment or the democratic processes that shape it. At the same time No One Left Behind highlights how contemporary art can serve not only as a reflective process on society but also as a proactive, collaborative movement for change. The transformative potential of this approach is not limited to disaster management; it has broader implications for urban planning and the development of different types of infrastructure. As we continue to grapple with the pressing challenges of climate change, urbanization, and societal inequality, the principles of feminist insurgent planning should serve as a beacon guiding us toward more inclusive, equitable, and just cities where no one is left behind.

Jason Waite is a curator, writer, and cultural worker focused on forms of practice producing agency. Recently working in sites of crisis amidst the detritus of capitalism, looking for tools and radical imaginaries for different ways of living and working together. He is part of the collective Don’t Follow the Wind curating an ongoing project inside the uninhabited Fukushima exclusion zone. Waite has co-curated The Real Thing?, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, Threat of Peace by Chim↑Pom at Art in General, New York and White Paper: The Law by Adelita Husni-Bey at Casco Art Institute, Utrecht where he was curator. He holds a PhD in Contemporary Art History and Theory from the University of Oxford, an MA in Art and Politics from Goldsmiths, London, and was a Helena Rubinstein Curatorial Fellow at the Whitney Museum ISP. He is the editor of Art Review Oxford and co-editor of the book Don’t Follow the Wind (2021) published by Sternberg Press. Waite is presently an affiliated fellow at the Panel on Planetary Thinking at Justus Liebig University.

Notes

[1] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable (London: Verso, 2009): 33.

[2] Eunseon Park, D.K. Yoon, Yeon-Woo Choi, “Leave no one Behind: Experiences of Persons with Disability after the 2017 Pohang Earthquake in South Korea,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 40, 2019: 1.

[3] Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: New York University, 2006).

[4] David R. Mitchell and Valerie Karr, Crises, Conflict and Disability: Ensuring Equality (New York: Routledge, 2014).

[5] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham: Duke University, 2019): 92.

[6] Eunseon Park, “페미니스트 저항 도시 계획 옥바라지 골목 안티 젠트리피케이션 운동 이야기[Feminist Insurgent City Planning: The Anti-Gentrification Movement Story of Okbaraji Alley],” 공간과사회 [Space and Society] 29, no. 2: 14-62.

[7] Ibid., 15.

[8] Eunseon Park email with the author March 6, 2022.