Are You Real Men? Queering the Militarized Masculinity in South Korea

Minji Chun

In March 2021, the first known transgender soldier in the South Korean Army, Hui-su Byun (1998–2021), committed suicide after being discharged in January 2020 for having undergone gender reassignment surgery while on leave. Despite her long fight to vindicate herself and secure the right to continue serving in the army as a “female” soldier, Byun’s request for reinstatement was peremptorily denied. Although the Korean court ultimately mandated her posthumous reinstatement and ruled the discharge unlawful and discriminatory,[1] it made no further statements about transgender individuals in general in the context of the nation’s military system. Byun’s case brought renewed attention to protecting queer individuals serving as soldiers and stimulated discussions about the need for a greater understanding of the queer community by all sectors of Korean society.

In Korea, the queer community and its allies have been advocating for more inclusive military policies, but progress has been slow. An example is Article 92-6 of the country’s military criminal act. Established in 1962, the article continues to outlaw same-sex activity among soldiers in the country’s predominantly male military and stipulates a maximum two-year prison sentence for engagement in anal intercourse and any other “indecent acts” between military personnel.[2] While Korea does not classify homosexuality as a criminal offense, queerness in the military is still regarded as a perversion to be punished as a misdeed per military disciplinary instructions.

In this climate, Korean queer artists have criticized the military from various perspectives: some have finished their military service while deliberately hiding their sexual identities and were later accused of the concealment; others have refused to be part of the system, rejecting an environment that reproduces homophobia and sexism as well as recognizes only cisgender heterosexuals as “real men.” In the scope of this essay, I will delve into the activities of three artists born in the 1980s—Nahwan Jeon (1984–2021), KyungMook Kim (b. 1985), and Jeram Yunghun Kang (b. 1985). They have addressed wide-ranging discrimination in the contemporary Korean army, which reinforces toxic masculinity and perpetuates harmful gender and sexual stereotypes. While employing different strategies and media, all these artists have argued that true masculinity is not defined by one’s ability to conform to traditional gender roles or engage in violent behavior. In this essay, I support their argument by showing how the agency and engagement demonstrated in their practices challenge the strict, seemingly generalizable notion of “being a man” in Korea, thereby rendering it open to queer evolution.

Prior to discussing individual artworks, it is essential to outline the distinctive features of the Korean army. According to Korea’s Constitution, every young, able-bodied man between the ages of 18 and 35 is required to serve in the military for 18 to 22 months. This institution of conscription stems from the geopolitical reality of the Korean peninsula. The continuous conflicts between North and South Korea, two nations separated by a heavily fortified border, combined with the active interference of major world powers such as the United States and China, establish Korea as a pivotal focal point for international relations. This situation underscores the necessity for a militarized approach to national security. According to cultural anthropologist Timothy Gitzen, militarization in the Korean context extends beyond the military’s influence on society and encompasses “the excess of military ideologies seeping into daily life and making those ideologies ordinary and even natural.”[3] In other words, “a militarized masculinity”—compellingly articulated by gender studiesscholar You-me Park—came to be one of the elements defining the postcolonial South Korean civic society.[4]

The normalized militarism in Korea manifests in different dimensions of Korean society, from mandatory military service by Korean men to the prevalence of military imagery in popular culture. A case in point is a variety show broadcast in Korea from 2013 to 2016 that followed Korean celebrities as they experienced military life in the armed forces. Called Jinjja Sanai (진짜 사나이, “Real Men”, which is also the title of a Koreanmilitary anthem), this show had celebrities showcased their physical abilities and highlighted the significance of camaraderie and unity in the military. According to media theorists Woori Han, Claire Shinhea Lee, and Ji Hoon Park, “the male viewers [of Jinjja Sanai] attempted to recover the hegemonic masculinity that they perceived to be under threat from changing gender relations” by advocating for the reactivation of conventional gender behaviors.[5] In other words, beyond the military system, the Korean media and its audience further perpetuate the idea that strength and masculinity are essential qualities of an “authentic” man. This pervasive cultural norm has exerted damaging effects on men who do not fit this narrow definition of masculinity, leading to feelings of inadequacy and pressure to conform. In this setting, queer existence is challenging to fathom.

Notwithstanding this reality, however, sexual minorities, including gay men, non-binary individuals, and transgender populations, have developed ways of surviving compulsory military service in an environment where male domination is entrenched within a heteronormative society.[6] Nahwan Jeon, a Korean queer artist and activist, is among those who have spoken out against the normative sexuality defined by the Korean military system. The army’s strict adherence to conventional masculine roles and heteronormative ideals has created a hostile environment for queer people. Against this backdrop, Jeon’s activism and advocacy foreground the intersectionality of gender, sexuality, and militarism, emphasizing the need for systemic change in Korea’s military and beyond. In 2017, Jeon condemned a detestable incident involving the Republic of Korea Army. The army hunted down homosexual soldiers after military investigators launched a probe in response to an online video of two male soldiers engaging in sexual activity. The investigation resulted in the punishment of at least 32 soldiers suspected of being homosexual. The artist shared the following sentiments:

The right to sexual self-determination is a fundamental human right that must be upheld and safeguarded, including during military service. Additionally, even if sexual activity between individuals requires some degree of restriction in the military environment, the form of restriction does not necessarily have to be the criminal penalty… This legal provision is disproportionate since it imposes criminal punishment for a behavior that may be addressed by disciplinary measures. Additionally, it is discriminatory as it punishes same-sex sexual activity differently from heterosexual engagement.[7]

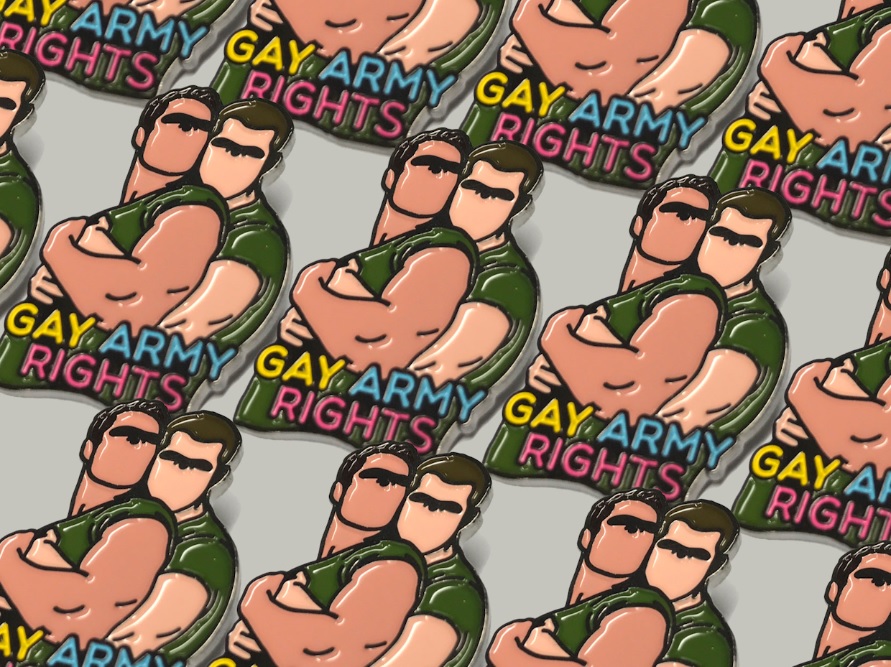

In response, Jeon launched his fund-raising project Gay Army Rights (2017), intended to support the Korean Gay Army Activity Network, also known as the Gun-Ivan Centre, which uses the slogan “Gay Army Rights Are Human Rights.”[8] This project is part of a broader emergence of queer culture in South Korea during the 2010s, characterized by the creation of new expressions that affirm unique identities and sexual orientations. According to activist and art critic Woong Nam, the mid-2010s denoted the beginning of the Korean queer community’s engagement with the culture of merchandise production in the arts. The culture’s expansion is reflected in the expression of confidence cultivated not only by the accumulation of experiences of living as queer but also by the constant production of various forms and languages that convey unconventional identity and sexual orientation.[9] The queer population educated in professional art and design institutions embarked on merchandising production, establishing links between genres such as independent publications, webtoons, design, visual arts, and one-person media.[10] This growth in queer community participation in merchandising production and interdisciplinary collaborations marks a significant turning point in Korean culture. Jeon’s project exemplifies this trend: by creating steel badges and color-printed postcards featuring a gay soldier couple hugging each other, Jeon raised awareness about the discrimination and harassment experienced by queer individuals in the military.

Jeon not only increased the visibility and representation of queer perspectives but was also devoted to fostering a sense of community empowerment and artistic expression. Wearing Jeon’s pin badge is an indisputable symbol of advocacy for policy changes—particularly the abolition of Article 92-6—which would allow queer individuals to serve freely without fear of persecution. Nam specifically emphasizes that Jeon, as one of the most community-oriented openly gay artists in Korea, “[sought] out different ways of meeting others’ gaze, representing and coexisting with them… even amid concerns of his exhibitions being reduced to part of a ‘message campaign.’”[11]

Through his art, Jeon not only asserts his individuality but also connects with broader cultural and political conversations surrounding queer identity and rights. By insisting on his own artistic autonomy while visually recalling the queer sensibility that characterizes some recent social movements, including the Seoul Queer Parade and the Daegu Queer Culture Festival, Jeon interacted with other artists of his generation and established relationships with the queer community and movement groups. For instance, Jeon expanded his artistic outreach by collaborating with the LGBTIQ Youth Support Center DDing Dong to organize exhibitions and workshops in 2018. His solo exhibition in 2019 was particularly notable for its inclusion of interviews with a diverse group of individuals, including 32 sexual minorities, drag queens, and people living with HIV. Until his death in 2021, queer solidarity was at the heart of his work, as he sought to create a platform for dialogues between different identities and perspectives so that marginalized voices could be heard and celebrated.

Meanwhile, filmmaker and media artist KyungMook Kim has addressed the precarity of the lives led by stigmatized groups, such as homosexuals, transsexuals, and sex workers. In 2015, Kim refused to enlist for compulsory military duty due to their pacifist beliefs, which led to a sentence of eighteen months in prison.[12]In a statement released in 2014, the artist noted that “the position of a sexual minority was the appearance of a socially underprivileged person far from power” and that “mental death is the reason why [they] instinctively [reject] the military system.”[13] They view their refusal as a form of resistance against a system that perpetuates discrimination and violence and humbly accept the risk of serving a prison sentence as the price to pay for making a small contribution toward substantial changes to come, including “an era of peace in which human rights are guaranteed in the military.”[14] Despite facing legal consequences for their beliefs, Kim has remained steadfast in their commitment to social justice and equality.

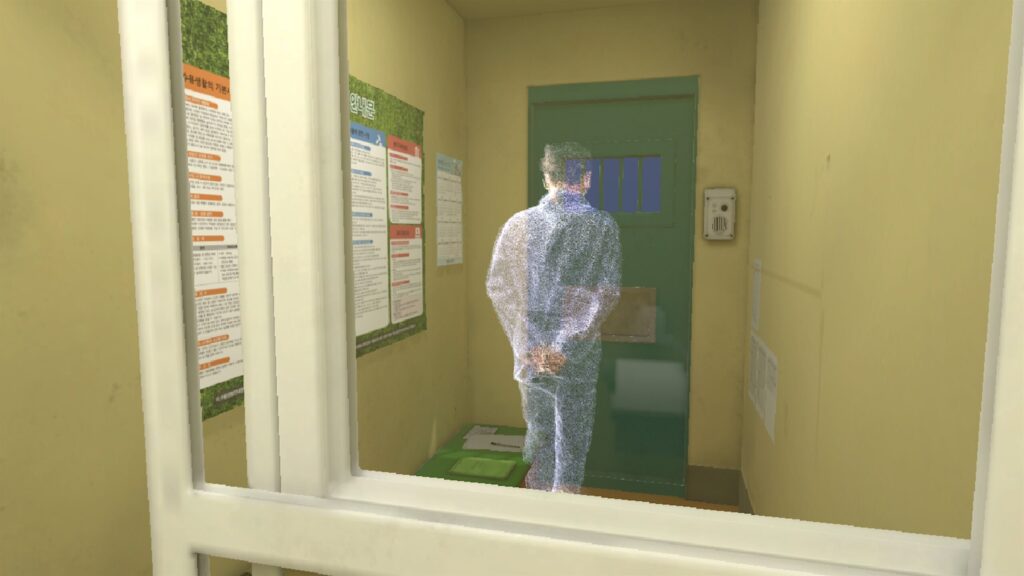

When Kim came out as gay, they were also placed in solitary confinement for more than a year, separated from other male prisoners, until their parole in 2016. According to an online note written by the artist to accompany a trailer for their virtual reality (VR) film 5.25m² (2022), solitary confinement, contrary to popular belief, “does not just mean imprisonment in a cramped space of 5.25 m². Prison is an institution of a legally binding oppressive order in which discipline and subsequent obedience are the top priority.”[15] Revisiting their own experience in the fortified correctional facility of the Seoul Detention Center, Kim produced 5.25m², which immerses viewers in a virtual representation of the small cell where Kim was confined.

Kim’s VR film was exhibited during their solo show Quarantine (Post Territory Ujeongguk, 22 May–23 August 2021). Whereas most virtual reality works transport viewers to fictional realms, 5.25m² is grounded in real-world settings. Viewers can interact with realistic re-enactments of personal stories set within the confines of a high-security facility, thereby granting access to experiences that would remain beyond reach. The VR film is similar to solitary confinement in the sense that it also gives a “place to experience [something] alone,” which is a common thread of the exhibition.[16] In virtual reality, the audience encounters a prisoner strolling like a transparent ghost while hearing the artist’s voice reads a letter to a friend serving in the military. The inmate often engages in repetitive motions, such as staring at a mirror or reading a book, before drifting off to sleep. They also practice meditation or stretching. The immersive experience invites viewers to reflect on their own relationship with power, authority, and punishment in the military system. The film powerfully conveys the toll that prison’s dehumanizing practices take on inmates, including the psychological impact of prolonged isolation and confinement.

Four years after being released, Kim was invited to participate in a program called Prison Inside Me, run by the Korean wellness center Happitory (a portmanteau of “happiness” and “factory”), which is designed to resemble a prison. At Happitory, guests must remain in a designated cell for twenty-four hours, during which they are prohibited from using electronic devices. Kim’s essay on this mock prison stay was included inSolitary (2022), edited by artist Tyler Coburn (b. 1983), a collection of ten site-specific writings about theexperience of being confined.[17] In the book, Kim reflects on his experience: “how much this place was unlike my former prison cell, where I woke up to the propaganda music of the Ministry of Justice,” which includes the lyrics “the more I follow the law, the better I feel.”[18] The artist precisely observes that the constant presence of propaganda music in their previous confinement symbolizes the oppressive nature of their surroundings, emphasizing the freedom and autonomy that they are denied.

(https://www.sapy.kr/SLY1_youcomein)

This essay’s final feature, Jeram Yunghun Kang, is based in Jeju, Korea, and was harassed and sexually molested while serving in the Korean military from 2008 and 2009. According to an interview with Amnesty International, after Kang completed his initial training in 2008, he was assigned to work as a “driver soldier,” a role viewed as the lowest and most “feminine” rank in the military. This assignment made him the target of harassment. Kang was repeatedly molested, kissed on the neck, and had his pants pulled down by superiors and other members of his unit.[19] Kang was outed and subsequently transferred to a psychiatric ward, where he was imprisoned for more than 100 days and forced to take antidepressants. He also attempted suicide twice. In this climate of ongoing oppression, few mental health resources were available to help him cope with his experience.

In the 2000s, the concept of kkonminam (꽃미남, “flower boy”) emerged in Korea as part of the worldwide trend known as “metrosexuality,” wherein men demonstrate a heightened concern for their physical appearance and engage in grooming practices traditionally associated with women.[20] Although the notion of flower boys has found followers in other nations and is also highly visible in Korean popular culture, it is generally unwelcome in Korea, where many perceive such individuals as a challenge to conventional masculinity and a departure from established societal norms. In particular, in the context of the military, such behaviors that deviate from traditional masculine norms and expectations are often met with increased surveillance and adverse reactions. While Kang might not have been directly labeled as a “kkonminam” or “flower boy,” his experiences reflect the broader tensions that arise from challenging traditional gender norms in a society where such deviations are often frowned upon, particularly in conservative institutions like the military.

Despite these difficulties, Kang became a vocal advocate for queer rights in Korea, using his art to raise awareness. In 2017, when a “gay witch hunt,” as previously recounted in Jeon’s work, was conducted in the Korean military by means of the gay dating app Jack’d, he experienced survivor’s guilt and realized that “if no one speaks, nothing changes.”[21] He felt an intense responsibility to make his voice heard and ultimately to bring a societal shift to the fore so that trauma could be understood productively as “a historical modifier inventing and promoting a cultural, legal, and political territory all its own” rather than a mere “circumscribed medical or theoretical condition.”[22]

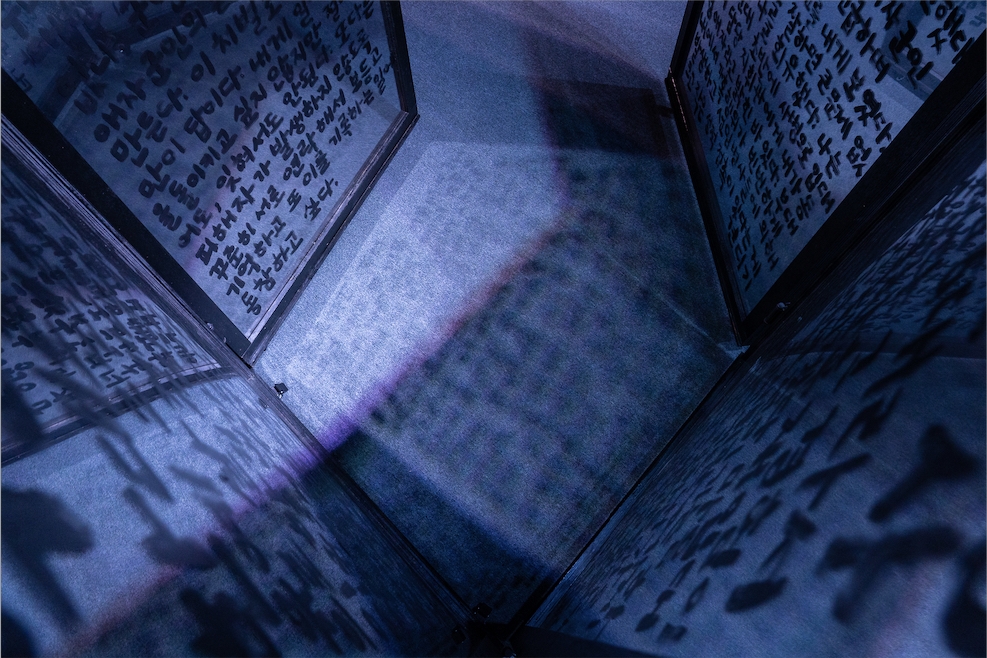

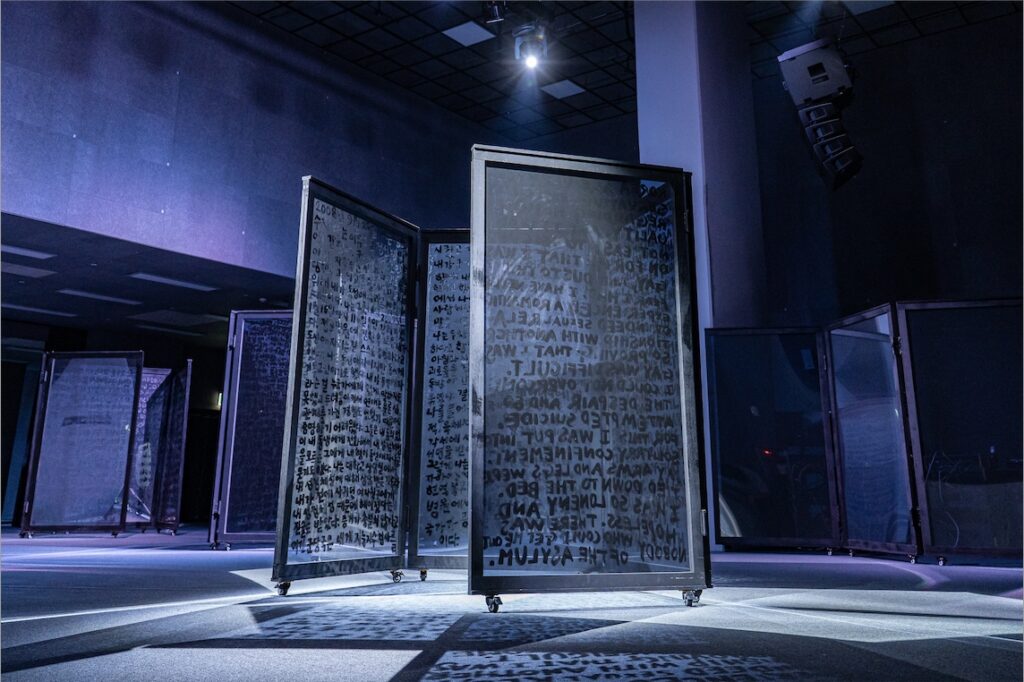

Kang’s You/We Come In I/We Come Out (2018–) is an installation series consisting of one or more letters that he wrote on large doors with reflective surfaces. The letters relate to the concealed stories of soldiers who faced punishment and imprisonment within the military due to their sexual orientation, which were often hidden and suppressed due to the stigma, discrimination, and potentially hostile environment within military institutions towards sexual minorities. Inside the exhibition, the doors enclose a narrow zone, and visitors are compelled to enter the space to read the letters. Those outside cannot see what is inside and can only look at their own reflections through a mirror film affixed to the exterior of the installation. Only those who “come in” are privy to the showcase, giving rise to a sense of intimacy and discretion. Within the circumscribed space, visitors can read the letters on the mirrors, which reflect their images behind the words and thus encourage them to relate themselves to the installation. The shadows cast by the letters, which vary depending on the position and angle of illumination, appear to be penetrating the floor as well as the visitors’ bodies. The purpose is to prevent the audience from understanding the installation as a detached narrative centering on another individual’s life; rather, it fosters a sense of connection and active participation in the conveyed personal anecdotes. Mirrors also add a layer of introspection, allowing visitors to reflect on their experiences and become part of a larger community that transcends individual narratives. Through this process, the soldiers’ concealed narrative “comes out” into the world.[23]

In You Come In I Come Out – A Letter from Asylum (2019), which is based on Kang’s own testimony, the ambiguity of the English word “asylum” is accentuated. Kang developed this series to demonstrate how the word can signify different meanings depending on context: Although one of its distinct interpretations, “confinement,” typically refers to imprisonment, it may also be used to describe a sanctuary. This dual meaning indicates that for sexual minorities, their surroundings can either be a prison or a haven, depending on the prevailing attitudes of individuals in society toward them. Similarly, You Come In We Come Out – Letters from Asylum (2021) features the testimonies of queer ex-soldiers whose experiences parallel Kang’s, thereby giving voice to their memories. Over the years, as evidenced by this work, “Letters” has replaced “A Letter” and “I” has become “We.” While the 2021 version maintains the installation format of the previous works, the change in title represents a transition and expansion from a personal account to a collective one, underscoring a sense of solidarity and unity. In Kang’s work—as in KyungMook Kim’s—solitary confinement is no longer an isolated space devoid of contact with the outside world but has been converted into a space where the voices, gazes, and movements of other individuals can intervene and occupy it.[24] By deploying affection and intimacy in his works, Kang uses strategies that invite rather than confront.

Being a soldier may naturally entail not only receiving physical training but also unconsciously abiding by primarily male-defined traditions. It might thus be described as a blind force of (human) nature. Considering the historical context of modern Korea, where the nation-state urgently sought to reclaim hegemonic masculinity for reconstruction after being under Japanese colonial control, it is not an exaggeration to state that the Korean military is a social class subordinate to the national system that helps to sustain masculine authority. Three artists’ practices examined in this essay, which did not constitute vehement, vociferous, direct resistance against a militaristic system, presumably cannot solve the persistent problem of the Korean army. Nonetheless, by espousing solidarity, resonance, empathy, and “queer kinship”[25] as recurrent themes, they have not only amplified the untold stories of marginalized segments of society but also encouraged a broader dialogue on queer identities and experiences in the military. These artists’ efforts to offer novel perspectives on masculinity, characterized by considerable contrapuntal complexity, are subtly but subversively permeating society. This is the arena where multiple masculinities, rather than one, emerge.

Acknowledgement

The author extends heartfelt thanks to the Nahwan Archive, KyungMook Kim, and Jeram Yunghun Kang for their generous permission to use the images in this publication.

Minji Chun is an art critic, curator, and translator working between Oxford and Seoul. Currently a doctoral candidate in History of Art at the University of Oxford, she focuses on socially engaged art in contemporary Korea, with a particular interest in overlooked histories and spaces. Her writings have been featured across a range of publications, including Hyundai Artlab, ArtAsiaPacific, Art&Market, and Wolganmisool (Monthly Art).

Notes

[1] “When based on [the] standards of women, there are no mental or physical disability grounds for dismissal,” the court said, ruling in Byun’s favor. “Transgender Soldier in South Korea Wins Posthumous Court Victory,” NBC News, 7 Oct. 2021, at www.nbcnews.com/news/world/south-korean-court-orders-posthumous-reinstatement-transgender-soldier-n1280990.

[2] Military Criminal Act [Kunhyŏngbŏp]. See Korean Law Information Centre, Ministry of Government Legislation at www.law.go.kr/%EB%B2%95%EB%A0%B9/%EA%B5%B0%ED%98%95%EB%B2%95.

[3] Timothy Gitzen, “Narratives of the Homoerotic Soldier: The Fleshiness of the South Korean Military,” Cultural Studies 36, no. 6 (2022): 1005–1032.

[4] You-me Park, “The Crucible of Sexual Violence: Militarized Masculinities and the Abjection of Life in Post-Crisis, Neoliberal South Korea,” Feminist Studies 42, no. 1 (2016): 17–40.

[6] The situation in South Korea presents a notable contrast to that of the United States, where queer individuals are currently allowed to serve openly in the military and no longer need to hide their sexual orientation. This change came about with the repeal of the anti-gay discrimination policy known as “Don’t ask, don’t tell” in 2011. Seongjo Jeong and Na-Young Lee, “Invisible Others: Institutional Homophobia and Identities of Sexual Minority in the Korean Military [Poiji annŭn kunindŭl: han’gung kundae nae tongsŏngaehyŏmowa sŏngsosuja chŏngch’esŏng],” The Korean Journal of Cultural Sociology 26, no. 3 (2018): 83–145.

[7] https://tumblbug.com/gayarmyrights/story.

[8] https://nahwanjeon.tumblr.com/gay-army-rights.

[9] “The cultural accessibility of the queer community is not limited to the intervention of established artists, designers, and expert groups in the issue of social consciousness. What is more noteworthy is the diversification of members’ desires within and outside queer organizations based on membership.” Woong Nam, “Bustling with Germinating Communities – A Walk to the Sexual Minorities’ Community [Parahanŭn k’ŏmyunit’i puryasŏng – sŏngsosuja k’ŏmyunit’i sanbohagi],” Webzine of Solidarity for LGBT Human Rights of Korea, 30 January 2016, lgbtpride.tistory.com/1154#footnote_link_1154_8.

[10] Woong Nam, “Subjugation and Discord in Contemporary Queer/Art [Tongshidae k’wiŏ/yesurŭi yesokkwa purhwa],” Seminar no. 2 (2019), www.zineseminar.com/wp/issue02/%eb%8f%99%ec%8b%9c%eb%8c%80-%ed%80%b4%ec%96%b4-%ec%98%88%ec%88%a0%ec%9d%98-%ec%98%88%ec%86%8d%ea%b3%bc-%eb%b6%88%ed%99%94.

[11] Woong Nam, “The Sun Shines on an Undreaming Mountain,” Sun, Sun, Sun, Here It Comes, exh. cat (Seoul: Factory 2, 2018).

[12] https://kyungmook.com/bio/.

[13] “Statement on the refusal to enlist by Kim KyungMook [Kimgyŏngmung pyŏngyŏkkŏbusogyŏnsŏ],” World Without War, 2014, at http://www.withoutwar.org/?p=9154&ckattempt=1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] https://kyungmook.com/5-25m%c2%b2-2022/.

[16] Seung-chan Baek, “’Memories of solitary confinement’ revisited in VR… Director KyungMook Kim held his first solo exhibition after being imprisoned for conscientious objection to military service, [VR-ro torabon ‘tokpangŭi kiŏk’t’…pyŏngyŏkkŏbu sugam ihu ch’ŏt kaeinjŏn yŏn kimgyŏngmung kamdok]” Kyunghyang Shinmun, 10 November 2021, https://www.khan.co.kr/culture/culture-general/article/202111101558001#c2b.

[17] https://tylercoburn.com/solitary.html.

[18] KyungMook Kim, “Solitary,” in Solitary, ed. Tyler Coburn (London: Sternberg Press, 2022), 28.

[19] Amnesty International, Serving in Silence: LGBTI People in South Korea’s Military, July 2019, https://www.amnistia.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Serving-in-Silence-LGBTI-People-in-South-Korea%E2%80%99s-Military.pdf, 32.

[20] Colby Miyose and Erika Engstrom, “Boys Over Flowers: Korean Soap Opera and the Blossoming of a New Masculinity,” Popular Culture Review 26, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 2–13.

[21] Bakhtawer Haider, You Come in, I Come Out | Content Free, 8 May 2019, content-free.net/news/you-come-in-i-come-out.

[22] Mark Jarzombek, “The Post-traumatic Turn and the Art of Walid Ra’ad and Krzysztof Wodiczko: From Theory to Trope to Beyond,” Trauma and Visuality in Modernity, eds. Lisa Saltzman and Eric M. Rosenberg (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2006), 260.

[23] Ju-yeon Park, “Sexual Minority, Jeju Person… Turning Personal Stories into ‘Our History’ [Sŏngsosuja, chejusaram… sajŏgin iyagirŭl ‘uriŭi yŏksa’ro],” Ilda, 6 November 2021, www.ildaro.com/9193.

[24] siren eun young jung, “Some Tendencies in Korean Queer Art Now [Chikŭm, Han’guk q’wiŏmisulŭi Ŏttŏn Kyŏnghyang],” Ilda, 26 November 2021, https://www.ildaro.com/9209.

[25] “This experience of together-in-difference, which I call queer kinship, is not flawless, but it does hold the potential to destabilize monocultural minoritarianism and to recollect the role of race, class, and gender nonconformity within the queer past.” Jennifer V. Evans, “Queer Kinship in Dangerous Times,” in The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship After Fascism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2023), 185.