The Possibilities of Change: An Interview with Yin Siyuan

Interview by Yuxiang Dong

This interview took place on February 2, 2023, through Zoom.

Yin Siyuan is an assistant professor at the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. Siyuan holds a Ph.D. in Communication from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her research spans the areas of feminist media studies, critical cultural studies, political economy, and social movements. Her work has appeared in leading journals, including Cultural Studies, Capital & Class, Media, Culture & Society, among others.

Dong: To begin with, I want to know about your relationship with Picun. How did Picun attract your attention? When was your first visit to Picun?

Yin: My initial interest was in a social group called young female migrant ( “打工妹”), and it was simply out of a sense of justice possessed by all scholars working in the field of “social justice” or “social engagement”. China has undergone economic reforms for several decades, yet the situation of female migrants differs significantly from that of girls born into middle-class families. Why is there such a disparity? At first, I focused on social inequality, but I soon realized this topic has been studied a lot. Problems such as structural inequality have already been examined. Therefore, I got more interested in “what to do?”, how can we make changes. Since I studied media communication, I became interested in the ways how social movement and activism use media or is related to media technology.

My doctoral dissertation proposal intended to address more than labor movement. Issues such as workers’ strikes and protests are certainly important. Over the past two decades, China has witnessed many labor movements in southern factories. These protests were severely suppressed by the police and state because there was no independent labor union. Although they were not reported by mainstream media, there were actually many studies of labor movements. My research aimed to go beyond substantial rights, concentrating on art as an entry point, but from the perspective of social engagement activism rather than aesthetics. Our understanding of labor and labor movements based on fundamental needs–labor rights. But I wanted to know if the group of several hundred million people has any social and cultural needs beyond economic substantial rights. Certainly, they have. But what are the specific needs and how do worker friends express these needs? In order to disrupt the whole market after the Reform and Opening Up, the neoliberalism, and the so called “(post) socialism,” actually a form of authoritarian capitalism, from the perspective of workers, I started to follow some NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations). As no independent labor unions is allowed in China, NGOs become an important form of organization. There are similar phenomena in other areas of the world, such as NGOs fighting for foreign workers’ rights in Singapore, Canada, and other countries.

I initially focused on the Migrant Women’s Club (打工妹之家), an NGO founded in 1995. They were one of the first NGOs working on cultural related initiatives. I first noticed the Migrant Workers Home online and found it interesting and unique. During their works, they propose the whole framework and culture of “new workers” to construct a new identity, emphasizing subjectivity. If we look at NGO-based services in China over the past twenty to thirty years, there has never been any activism or resistance of this level. In 2016, I went to Picun to do fieldwork and it was an interesting process. I contacted Xu Duo first. Then, I stayed in Beijing for a while every winter and summer break. I spent quite a lot of time doing fieldwork. Thanks to social media, we attended some activities together, including academic events, and others organized by them, during which I got to know people like Wang Dezhi. While writing my dissertation, I was pretty positive and optimistic. But in the past couple of years, I started to think about its problem: new workers was first to fight against the discriminatory discourse of peasant workers (农民工) and construct a new identity of subjectivity. However, whether it is an imagination or a construction of subjectivity, new workers are actually more about its “political correspondence (政治对应).”

Dong: What do you mean by “political correspondence”?

Yin: I do not know if you are aware that many of these people were “fans of Mao Zedong” (毛粉). I was once a typical left-wing youth and would romanticize the socialist form in Maoist era. The new workers correspond to a political identity which considers that “workers are the masters of the country” (工人当家作主) in the Maoist era. I read an article written by Wen Tiejun (温铁军) about the corresponding relationship of contemporary migrant workers and middle class with workers and peasants in the Maoist era. I cannot agree more with the point in the article that workers were a privileged class during the Maoist era, while peasants were in a miserable situation, both economically and financially. Peasants suffered from discrimination–no one would look up to them then. It seemed to me that workers enjoyed a sense of superiority, while from my perspective, the idealized equality of many people’ nostalgia today was actually never achieved. In the 80s and 90s, many migrant workers came to the city. People in cities were discriminatory against peasants, considering them as outdated and fool. The urban-rural dualism (城乡二元论) was common at the beginning of the 2000s, and it still exists today although the situation is improved. This discrimination did not emerge after the Reform and Opening Up. Instead, it was a product of the Maoist era. The city workers at that time correspond to today’s urban middle-class. The concept of new workers definitely has its positive and resistant aspects. However, it does not face the future but only look for a kind of political correspondence in the past, new workers can gain a kind of legitimacy but also have a kind of “socialist nostalgia” or “romanticizing.” These is a mismatch in this correspondence. I am not sure whether new workers are aware of the privilege of workers at that time. If we project into the future, the imagination of political and social equity or freedom, new workers may not be able to bring people to the final ideal status, as there are some problems regarding imagination and discourse subjectivity. This is the problem I have been thinking about over the past two years.

I certainly have a lot of empathy and solidarity with them and can feel a strong sense of unity. Is it necessary to ask them (new workers) to think and examine the existence of workers in the Maoist era? It is not their duty and they are not obliged to do such detailed research. However, holding the flag of Mao is, on the one hand, a strategy of political legitimacy for their existence; on the other hand, many people are sincerely nostalgic about that era, feeling that they correspond to workers at that time. There were many good things back then, like collectivism. However, I have not seen many honest reflections on the problems of that time and some contemporary problems that are stemmed from problems of that time. Today, all problems are pointed to the capital. That is to say, all problems of the Reform and Opening Up are all brought by the capital. While the capital is certainly a problem, power may cause more problems than the capital in the specific context of contemporary China. It is understandable that the New Workers cannot fight against these things directly because they would have no space to exist. Nonetheless, during my interaction with them, I do not think they reflected on this problem, especially some of them even tried to justify all government’s actions. They believe that the government is always good and they should use the government to fight against the capital. They were not even willing to listen if you tried to explain that there were many “red capitalists” (红色资本家) or the close entanglement of political capital and economic capital. They are actually under great influence of the mainstream official discourse and explain everything with “Chinese characteristics” (中国特色). I was pretty frustrated during those times. However, they are not obliged to dig deep into social problems in great detail like us. They have done many extraordinary things, the reason why I follow them constantly and can gain a lot of energy.

Dong: What you have talked about is related to the next question: What is the relationship between the Migrant Workers Home in Picun and the government?

Yin: There are many layers when it comes to their relationship with the government, not just a general term of government. During their earlier years, also the Migrant Women’s Club, there was a leader perhaps in the cultural bureau of Chaoyang district, or other district level government bureau, who really appreciated their activities and provided many supports such as activity venues. We all know that in China, if you have a government leader’s supports, things will be much easier. Thus, I understand that they want to keep a relationship with the government for practical reasons. For example, Sun Heng (孙恒) received a lot of recognitions from the government, which can be very meaningful for their existence. However, what I was talking about was something more abstract, something on the political level. We can try to interpret it. It is unrealistic to ask them how to negotiate with the government when they really want to do something. But in terms of academic and theoretical level and the future “blueprint,” it is still worth considering what political imagination we should have.

Another thing that I want to mention: the band was renamed as the “Barn” (谷仓) from the New Workers Band. I asked Xu Duo (许多) specifically about the name change. He explained to me quite simply. It sounds to me that it is more about political consideration, but not completely pressure. They have been engaging with rural reconstruction (乡建) and the government is also promoting rural reconstruction and “return to the rural” (返乡). So, they want to ride the wave. On the other hand, they feel that new workers have some political limitations because labor movements are too sensitive in China. But rural reconstruction or something feels more cultural may tend to romanticize the rural.

Dong: When doing your fieldwork in Picun, did you have any friends, partners, or colleagues that impressed you? or anything interesting?

Yin: Everyone has their own characters. Xu Duo has a kind of uninhibited artistic personality. But he definitely has his own thoughts. There was a bit of dissentious argument during my first interview with him when we were discussing the significance of gender and class inequity. My opinion was that they were equally important as absolute equity and freedom require an absolute revolution. Xu Duo however thought that gender inequity is secondary to class inequity at that time (2016). It was a typical opinion among people who believe orthodoxic Marxism not only in China but also worldwide. Historically, class has always been prioritized in most labor movements no matter whether it was in the West, the Soviet Union, or China. Gender issue is always secondary–we have to deal with class problems first, and then talk about gender oppression. I think it is very interesting that I had an argument with Xu Duo about this then. In recent years, I feel that he may have new insights and understanding of this field as some of his WeChat moments pay attention to the gender issue.

I think it is problematic that we have so much orthodoxic emphasis on the class in the mainstream environment of the labor care. It lacks intersectional perspective. Class issue is important. If you want an absolute revolution, capitalism is definitely evil, but patriarchy is a power structure that exists much longer than capitalism, and capitalism adopts patriarchy. You are blind to or trivialize this problem, or even hold a misogynistic opinion that “(dealing with gender issues) is dividing our unity.” From my perspective, these men or male workers are not willing to give up their male privilege and cannot face the fact that patriarchy has its supremacy in politics, economics, culture, society, and mentality. It is hard for a revolution to truly engage more people. It finally still ends up replicating the so called “revolutionary discourse” of the past.

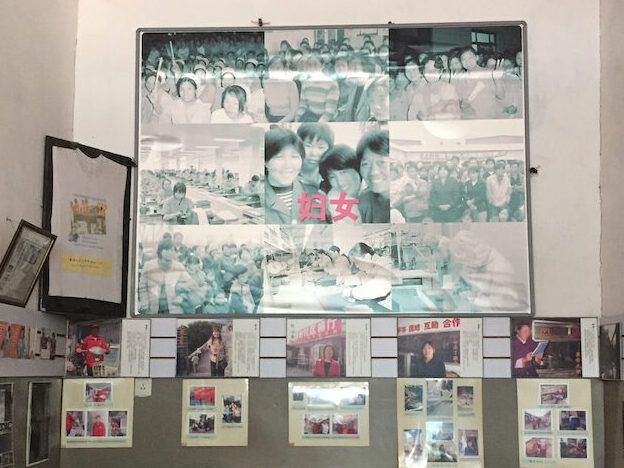

Dong: You had a talk in the Picun Literature Group entitled “Women in China and the US and Feminist Movements Over A Hundred Years (中国和美国的妇女及女权运动百年史).” What was your motivation for this activity? Why did you choose a topic about feminism to deliver in Picun? How was the participation of the members of the group?

Yin: It was the summer of 2019, I just finished my Ph.D. and was invited by Zhang Huiyu (张慧瑜) to have a talk on a self-proposed topic. I have always been interested in feminist movements and will talk about related topics in my own classes. During my fieldwork, I found that the general framework of new workers in Picun marginalizes feminist politics, gender inequality, and related issues. This brought me to the idea of giving a talk about the comparisons between China and the U.S. First, I am pretty familiar with the history of feminist movements in both countries. Second, I deliberately chose to make this comparison to inform people to suspect official controlled discourses, such as “the West is terrible” or “China against America.” There are many similarities between the West and non-West in some fields of resistance with many unities. Although with different historical and cultural features, I wanted people to see the possibilities to connect. The purpose was the great unity of people all over the world.

There was a high level of attendance, including almost everyone in the literature group, some student volunteers, probably from Taiwan, and a journalist. I mainly focused on historical events, talking about what happened indeed, instead of theories. It ended well with a heated discussion after my talk. Some ideas were not totally understood due to the lack of background knowledge. However, people started to talk about women and their problems, such as the division of household work, gender-based violence, and discrimination in the workplace. It was quite interesting. An article was later inspired by this talk. I think women’s movements in China have their own unique historical genealogy from the end of the 19th century to the present, despite some similarities with the West. This was what I wanted to communicate with worker friends in Picun. I had a strong sense of mission to inform them the fact that women’s movements and labor struggle were closely linked together, which was a possibility of connection.

Dong: Could you talk about class politics and gender politics in Picun in more detail? In previous interviews, we discover that these problems can be approached from different perspectives. For example, the New Workers’ Video Collective, organized by curator Song Yi and Wang Dezhi, held a workshop and filmed a short documentary called “Love, Marriage, and Family of Chinese Migrant Workers: Community Workshop.” They claimed that class and gender issues were reflected by very material aspects such as marriage and housing. In your opinion, how does gender politics exist in Picun where the context focuses more on class politics?

Yin: This leads us back to the relationship between patriarchy and capitalism. They pay attention to material aspects, such as marriage and housing, of gender issues, which lead to the objectification of male and female relationships in the working class. This is a consequence under mutual influence of capitalism and patriarchy. This objectified relationship also exists in the middle class, wealthy elites, and the upper class, which ultimately results in the private ownership in a family, including the division of household work since it is a product of patriarchy. Social concepts and structures will absolutely cause normative expectation and objectification. In traditional social concepts in both the East and the West, women expect men to provide material supports, and men expect women to do housework in return in any social class. Doing housework is a gender division of labor, which exists across social classes. But the working class is underprivileged, especially working-class women do not have enough material support to balance the male-female relationship as independent middle-class women. This problem is exacerbated. This is why it appears that middle-class marriages care more about love. They do not deny the importance of the material, yet consider it as a precondition, which they do not need to worry too much about. I do agree that they call this relationship as a “mutual objectification.” This objectified relationship not only exist in the working class. But due to underprivileged status of the working class men and women in the economic structure, the problems with material get more prominent. Also due to this patriarchal structure, many women are willing to use marriage to improve their social class. This is the so-called marry up (上嫁)–“women marry up, men marry down (女上嫁,男下娶).” Women provide emotional value, fertility value, and housework in exchange for men’s financial supports. During the formation of masculinity and femininity in a patriarchal culture, a man’s patriarchal dignity, no matter how poor he is, will never allow him to see a woman as the center of a family, who is in charge and make money. However, many women of both working and middle classes are finically supporting their families now. Women domestic workers can earn a lot, but their husbands are still in charge at home although they probably do not have any income. It is the same case in middle class families. They still need this traditional male-dominated relationship or “men are superior to women (男尊女卑),” a little bit exaggerated.

In addition to objectification, alienation is another problem under these circumstances that we need to consider. The masculinity or femininity defined by patriarchy makes people in male and female relationships difficult to look for a true relationship of mutual respect and equity. This problem is also very common in middle class families. In addition, it is not only a Chinese problem but also a global one. Because during the industrial revolution, working class women cannot be housewives. Being housewives is a privilege for the middle class. But now middle-class women have to work, take care of the family, as well as do household works. Working class women have always been working besides household works, since their husbands’ income is not enough to support the family. I especially like a sentence in an article entitled “The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism” written by Heidi Hartmann in the 1970s: working class men “have more to lose than their chains.” They actually enjoyed the emotional value provided by women. For example, in a relationship, a woman has to show obedience, admiration, and other emotional values towards a man, also she needs to give birth and make corresponding sacrifices, as well as doing household works. With this respect, men of working and middle classes are in the same position of privilege. I do not think we can tackle real problems if we deny this reality or only attribute it to class. On the other hand, if we only attribute it to class, working class men may be finally happy or even became middle class men. But the situation of women will not improve. Their situation in male and female relationships will not change with class.

Dong: What are the characteristics of the Migrant Workers Home’s practices do you appreciate?

Yin: The existence of the Migrant Workers Home is quite a hybrid model. On the one hand, there are some services that are not very political, such as the library, community activities, and providing activity spaces for children. These are typical NGO services that came from Hong Kong through southern cities like Guangzhou and Suzhou in the 1990s. On the other hand, the New Workers’ Band and the museum are quite unique, more about expressing towards the society. These two parts have different focuses, although their participants are the same: local residents in Picun or new workers. The former basically has nothing to do with politics and is more like a social service community building. Residents in Picun are not interested in concepts such as the new workers. Nonetheless, there is a small conscious minority, a kind of the “awakening of the labouring classes” a concept conceived by the E. P. Thompson, including participants of the literature group, the band who pays long term attention to new workers, and people who really care about their museum and the political, the construction of subjectivity, and the antagonistic they want to express. The number of this kind of people is very small. The “small” does not mean “a few.” There definitely more than a few but can be thousands of ten thousand. However, compared with three hundred million migrant workers, it is objective to say that this group is relatively small. For most worker friends, their cultural needs and consumption are still pop culture. It is understandable. The audience number for the political is very small. But at the same time, we have such a massive population of workers. Our perspectives are very limited.

Dong: Has the Migrant Workers Home tried to use different media to attract more audiences? For instance, Picun Literature, a publication of the literature group, is also published online and can be downloaded from cloud drive. Each issue of the publication includes some knowledge of the law, introducing related laws for workers to defend their rights. How effective are these media?

Yin: I believe they have been using different media very actively. But finally, only a few people can be attracted and mobilized by them. Again, “a few” is definitely more than 1,000 but perhaps at least 10,000, a conservative estimate. But it is a relatively small amount compared to massive population of workers in China. Therefore, I do not think the Migrant Workers Home has a large-scale influence on the society. For them, media certainly brings many opportunities. But in terms of the actual impact, the power of mobilization is not from the media per se but the value of the things they are doing. In an environment of digital media, especially for labor activism, offline connection should be the first step, which should be prior to online presence. We should establish our own base offline and then gradually build online presence. It is also because of the characteristics of this group at large. In reality, the country’s politics and social environment and media discourses do not have the agenda of labor resistance. Labor movements in the southern provinces are motivated by substantial rights. We do not have an environment to cultivate cultural resistance, like Pierre Bourdieu’s “habitus” or Michel Foucault’s “subjectivity.” Given this situation, it is hard to reach out and mobilize more people if you purely rely on online presence at the beginning. For people like Xu Duo, they actually established the New Workers Band at first and then had a series of activities like the Migrant Workers Home. Broadly speaking, music is also a kind of medium. I like some of Xu’s songs, especially the newest two: Earth (人间) and Partisans in Winter (冬天里的游击队员). They are affective still because their contents move and mobilize you. In earlier years, they performed at construction sites, which was very local. This is very important that people tend to ignore in the digital environment as we think digital is all good! We can have the revolution! Revolution is certainly not that easy. When talking about media and the relationship between media and other things, we need to contextualize the relationship and situate it within bigger, the whole social structure and mechanism to understand. Thus, we can better understand why it is in the current status and what impacts it will have.

Dong: Some members of the Migrant Workers Home used to be workers. While they transferred from manual labor to intellectual labor in recent years, many residents in Picun are still doing physical works. What is your observation of the coexistence of manual labor and intellectual labor in Picun?

Yin: The distinction between manual labor and intellectual labor is a byproduct of capitalist modernization, which emerged following the industrial revolution, due to the division of labor that needs to distinguish factory workers and managers. This distinction destroyed class solidarity. Strictly speaking, I do not think the division between manual labor and intellectual labor is applicable to distinguish what new workers are currently doing. I think they are more like “organic intellectuals” that Antonio Gramsci argued. They are not doing any kind of work, at least not works strictly defined by the industry. The organization is not even a typical NGO. Nonetheless, it is hard to say if they are intellectual, knowledge workers. They are very organic and have lots of connections. They may not understand what they are doing within the framework of labor. Instead, they may say that they are doing activism or service. From conceptual perspective, activism can certainly be seen as a kind of labor, but this kind of labor is not professionalized or institutionalized.

I think Xu Duo is a freelancer and an activist in art, literature, and culture. He possesses skills and talent as an artist while having his own NGO. Wang Dezhi has been providing the primary financial resources for them by running social enterprises. These jobs separate them from other artists and artistic workers with a more independent status. I do not think the concept of a knowledge worker is enough to summarize what they are doing right now, or their whole identity. They are independent and free workers of literary, art and culture, NGO, social service, activism, and organic intellectual at the same time. As for Sun Heng, I do not have much connection with him, but I have read many of his works on social media and have heard people talking about his experiences, which is not limited to working experiences. I think he is a guy with strong dedications, between worker and art and literary people, a typical “organic intellectual.”

Dong: What is your role?

Yin: This is the question that critical scholars, especially scholars who are doing engaged scholarship, have to face. People always ask: “What change can you bring by studying the so-called underprivileged, marginalized groups?” “You are actually capitalizing on them, as all you have done is writing essays and getting academic rank promotion, which bring you a middle-class academic life. What is your ‘social engagement’ exactly?” From my perspective, there are a variety of forms of engagement. Being ready and having an intention of “engaging any time” is the most important and basic way of engagement. Most fundamentally, you can pay attention to their activities, such as crowd source funding. You can donate. As for research and writing, I do admit that we capitalize on them, but in the meantime, we also inform students in classes about these things when educating the next generation. We learn from the accumulated knowledge of organic intellectuals written by Antonio Gramsci and conscious minority written by E.P. Thomson. Knowledge passes from one generation to another, corrects itself and expands its imagination, then it criticizes the society and makes changes through generations. In this regard, I think there is still a lot to do. Although we should certainly not exaggerate academic influence or believe that academic research is the most important, it is unnecessary to totally deny the meaning of the academic. It definitely has very important meaning. For example, Karl Marx wrote The German Ideology and On Capital while engaging with European labor movements, which are critical academic works that influence the whole world for hundred years.

I feel frustrated that what an individual can do is really limited. But I just do what I can do. There are basic things like donating. I think delivering lecture is also interesting. In the recent two years, I have done research on Canadian labor issues, so I would love to give another talk in Picun to introduce issues confronted by Canadian immigrants and workers. I like to present commonalities for everyone to see and link things together through historical lines. The most promising thing is that people realize all these fights have results. Although most of them lose, there are still lots of positive results. One success in a thousand fights gives us hope, and I like this hope.

Dong: Yes, that is all my questions. Thank you!

Yin: Thanks for inviting me for the interview. Picun is really unique. Intellectuals pay a lot of attentions to them all these years. Maybe they are used to the situation that many people just come, do some research, and then leave. It is understandable that they have got negative feelings about it because from their perspectives, you really cannot bring anything. It is also quite an indirect and remote influence when I teach my students about this. However, there are all kinds of resistance and fights for equality, freedom, and liberation all over the world both historically and presently, and I am sure that these will continue in the future. This is quite exciting and inspiring.

Translation by Ningxin Chen, Sichuan Fine Arts Institute