The Promise it Makes: Art and the Afro-futuristic Future

By Primrose Paul

As a student of art history, I have found myself interested in the use of visual language and cultural production by black artists as a means of communicating a message of freedom and liberation. Freedom remains a dream for us as this world has for too long made promises of freedom and liberation that have never been fulfilled. One can look to the American dream as an example that says that life should be better, richer, and fuller for everyone, with opportunities for each according to their ability or achievement and regardless of social class or birth circumstances. This belief in upward social mobility comes into conflict with a society predicated on forms of race and class-based oppression. For us to be free, we are called to use our imaginations to create an alternate reality which frees us from the chains of the existing structure that binds us; a white supremist capitalist patriarchy. As we are immersed in a visual world, we turn to black artists as the painters (symbolic or actual) to give us a visual perspective of what a future based on the foundations of Afrofuturism might look like. In this essay, my goal is to offer a critique of the cultural marketplace with focus on the effects of the commodification of black visual art and the specific forms of subjectivity that arise when an art market has demands from black artists to make works which depict realism of the issues within the black community as a form of activism. Although these works aim to bring awareness to the viewer, they exploit notions of cultural essentialism resulting to the perpetuation of stereotypes that are then commodified within the art institutions. I use Afrofuturism as an antithesis of the white supremist capitalist patriarchy with emphasis on using one’s imagination as an act of confronting of our current state of affairs. Many people feel trapped and alienated by their working lives which results to consumption of forms of escapism as a relief of the burdens of modernity which include individualism, debt, or awaiting environmental catastrophes. Technology and mass media offer platforms for us to consume from the comfort of homes, isolated and alienated. On top of that, the cultural marketplace becomes a very effective place for ideological domination to occur in the most subtle of ways because no longer does one have to send an army that goes to a foreign nation for conquest, domination can now occur culturally, with the click of a button.

The term Afrofuturism in the confines of the black experience in America was coined in 1994 by Mark Dery in his essay “Black to the Future”: Afrofuturism is defined as a speculative fiction that treats African American themes and addresses African American concerns in the context of the twentieth century techno-culture and, more generally, African American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future. [1] Confining Afrofuturism to the African American experience in this sense becomes problematic because it fails to acknowledge other black communities that were and continue to be affected by the colonial rule of white supremacy across the world. This skews the black experience into a monolith from the point of view of the black individual in America. Additionally, before Mark Dery coined this term, speculative fiction across Africa was widespread with authors such as Ngūgī wa Thiong’o, Daniel O. Fagunwa, Elechi Amadi, and many more who wrote works that engage African society in the context of a futuristic fantasy incorporating mythology, magic, and superstition. Speculative fiction is also rooted in the oral traditions passed down intergenerationally, so elements of Afrofuturism have always been present in Africa but are often overlooked because of the superstition surrounding African traditions (especially those speaking of magic) due to the undeniable consequences of colonialism. So, we become aware that a large portion of Afrofuturism entails the use of fantasy or magic which allows one’s imagination to avoid rationality and explore the boundaries of new possibilities. Dike Okoro states in his essay “Futuristic Themes and Science Fiction in Modern African Literature” that:

These African authors recreate an African world where social, political, and economic situations share symbiotic ties to the beliefs or mythical realities presented through narrative techniques such as magical realism or fantasy. Hence magical realism is used as an esthetic of necessity to situate postcolonial realities and imagined worlds that satirize or illustrate social realism and other forms of postcolonial African crisis. [2]

These crises are not to be understood as being unique to Africa, but rather, offer a parallel to the modern reality more generally. We first notice that for a body to want to escape a reality that is driven by underlying tensions of inequalities in modernity, it first has to confront its past then speculate on what it anticipates for in its future. How different would our lives be if a white supremist capitalist patriarchy was eradicated?

In this essay, I will analyze works by Omoruyi Eghosa, Emmanuel Massillon, and Sam Onche to explore the broader scope of Afrofuturism. I will be exploring the role of visual language and subjectivity in their works and introducing the viewer to their different approaches to activism. Here, I also look into the paradox of the black artist as an individual who can trigger change but also perpetuates resistance to change. This is a characteristic I noticed in a capitalist culture, where revolutionaries are lured into the cycle of mass production where the promise of recognition and financial compensation overcome the potential for their work to criticize the system they work within and bring about the change they aspire to work towards. For example, if a market demands for works that can be contextualized along the subject of racial domination or stereotypes, there are artists who will depict these subjects offering the suffering or trauma of the black individual as a site for one to make money. Although the intention of the artist may be educating the masses on the lived experience of black individuals, pain and suffering continue to be perpetuated and we see an increase of works of this nature in the institutional art world. The black experience is centered around Afrofuturism because of the identity of these artists and writers as black which poses the question asked by Mark Dery in his interview with Samuel Delaney, “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”.[3] This is not a question that can easily be answered as we will see later in this essay. However, part of answering this question involves seeing how blackness is viewed in relation to freedom and why it is important to look at black artists when we think of it. As a group that has gone through domination and emerged on the other side, freedom is closely linked to blackness. In bell hook’s essay, “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance”, she analyzes the film Hairspray stating: Blackness – the culture, the music, the people – is associated with pleasure as well as death and decay. When Traci says she wants to be black, blackness becomes a metaphor for freedom, an end to boundaries. Blackness is vital not because it represents the ‘primitive’ but because it invites engagement in a revolutionary ethos that dares challenge and disrupt the status quo.[4] There have been several instances in contemporary culture where blackness is seen as representing rebellion against social norms. Common in mass media, we see non-black individuals have moments when they act out and closely link themselves to blackness in order to achieve authentic expression as blackness equates freedom. Most commonly seen in the music industry where young non-black rappers take up the persona of a black individual to express themselves, make profit and later on go back to their whiteness when transgression is achieved.

Reimagining the Past

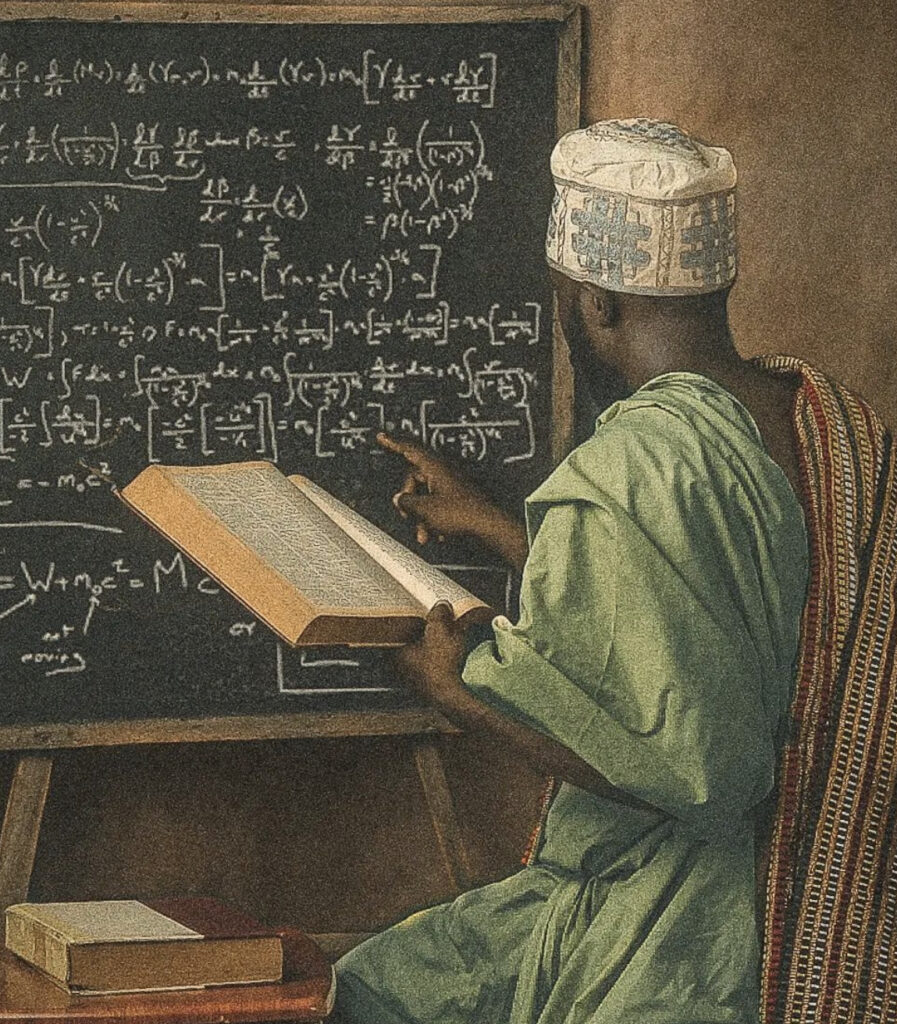

Given this sentiment, it is interesting to see how freedom and blackness are intertwined. I will first look at the works of Nigerian artist Omoruyi Eghosa, famously known as Tobyd the photographer. Eghosa works in digital manipulation of images, which incorporate references from parts of art history that he has found interesting. With admiration for how the old masters depicted their subjects, Eghosa has created a style that uses renaissance ideals including the use of biblical characters into his photography. Prior to virtually meeting him, my interest in his work came from his depiction of black bodies. There is a delicate nature that he shows black people immersing the viewer to focus on what is beautiful instead of over analysis of a deeper contextualized meaning.

Both works show black women posed against dark backgrounds as they are placed along with natural elements like flowers and birds. Our conversation began by discussing his art practice, which he described as a spontaneous exercise, except on rare occasions when he plans out a sketch beforehand. Recently, Eghosa has been working on re-imagining biblical stories. Growing up in Nigeria, he always had access to children’s books depicting images from the bible, but he noticed that no one in these images looked like him. Instead, he sought to imaginatively insert himself into these stories and transform them, to reflect his own experience. For Eghosa, the importance of inserting himself into these stories serves as a reminder that there are lessons that he learned from reading these books that affected his entire outlook on life. “Morally speaking, as a young child, these are stories you hear, and they serve as warnings about what happens when you disobey God or what you can or cannot do. It is undeniable that these stories had an impact on how I see the world today. Or even how I think Jesus looks like. They are part of me, and I must see myself in them”. [5] Combining both art and technology, Eghosa produces photographs that mimic renaissance paintings often tricking the eye of the viewer into thinking that his images are painted by hand. The Commandments, 2023 shows Eghosa as Moses on Mount Sinai with the ten commandments while in Thomas, 2023, Eghosa takes up the role of Christ and his disciples after the resurrection.

The black artist occupies a very interesting position in the cultural industry, one which their work is in great demand after many years of neglect by the art world. It was not until recently that we have seen works from black artists saturating the market and even then, when one walks into art institutions, the main subject depicted explores concepts of cultural essentialism. Often the question asked by the viewer is how race has been a defining feature in the work that the artist makes or how is it represented in the work created. For an industry that is looking to show how diverse and inclusive it is, there is a hunger to show work that can spark conversations on the black experience, especially one that talks of the stereotypes ascribed to this community. Living in a society that thrives on the domination of the other creates a dynamic in which culture becomes a product to be consumed resulting to the commodification of the blackness. The cultural marketplace creates a demand for black artists, on top of that, it asks for subject matter that is politically charged to spark conversations on difference or the effects of racism. For the most part, these works can start conversations but without interlocking the subject of race with capitalism and the patriarchy, they fail to fully critique systems of domination. Part of understanding the black experience is also understanding the role that pain plays in this community and how that pain translates into visual art. Posing a question to Eghosa on his thoughts about this pain always being representative in numerous works of art he answered:

“With a lot of concentration on activism through art especially those talking of race, we often forget the beauty of our community as we are immersed in the pain we historically hold. When you put your hands into social issues, there is room for controversy and backlash. How it is received by the viewers and what the artist intends to deliver leaves ambiguity of the intention versus the impact. Furthermore, I think it is easier for renown artists because they have already made it that controversy would not affect them in the same way it would for me. It is a tricky area for upcoming artists. But in the end, I think for me, celebrating the beauty, smartness, and positivism of black people is my way of being an activist for my community. There have been numerous great black people, but why have we not heard about them?” [6]

The boom in demand from galleries, curators, collectors, and museums to show works from black artists truly creates room for visibility to show what the black experience entails but it also perpetuates the commodification of blackness as something that can be controlled by the consumer market. So, if the consumers want subjects that remind them of racial domination or protesting institutions; we see works like these emerge in the art market and we can look at works that arose from protests in 2020.

Amy Sherald’s portrait of Breonna Taylor is a great example of how pain and suffering of the black community can be commodified by an institution acquiring a work of art and overall, it fails to substantial critique the structure of domination. Works like this offer a platform to theorize on the change and promise it but never actualize it. We have witnessed works that depict the victims of police brutality before. They create the illusion of change via representation of issues but in practice, they only offer a symbolic change by having the viewer talk about current issues and move on to the next piece of work. Additionally, it provides a site where the members of the privileged class can show their progressiveness or having political consciousness as a form of social appeal and acceptance of inclusivity. Being that art is produced in a capitalist environment, the problem begins when these works of art fall into the trap of mass production because the art market demands specific subjectivity, and their art becomes like any other product in a monopoly capitalist society that is mass produced to the point where impact is not made. Hooks remarks:

Concurrently, marginalized groups, deemed Other, who have been ignored, rendered invisible, can be seduced by the emphasis on Otherness, by its commodification, because it offers the promise of recognition and reconciliation. When the dominant culture demands that the Other be offered as sign that progressive political change is taking place, that the American Dream can indeed be inclusive of difference, it invites a resurgence of essentialist cultural nationalism. The acknowledged Other must assume recognizable forms. Hence it is not African American culture formed in resistance to contemporary situations that surfaces, but nostalgic evocation of a “glorious past”. And even though the focus is often on the ways this past was “superior” to the present, this cultural narrative relies on the stereotype of the “primitive. [7]

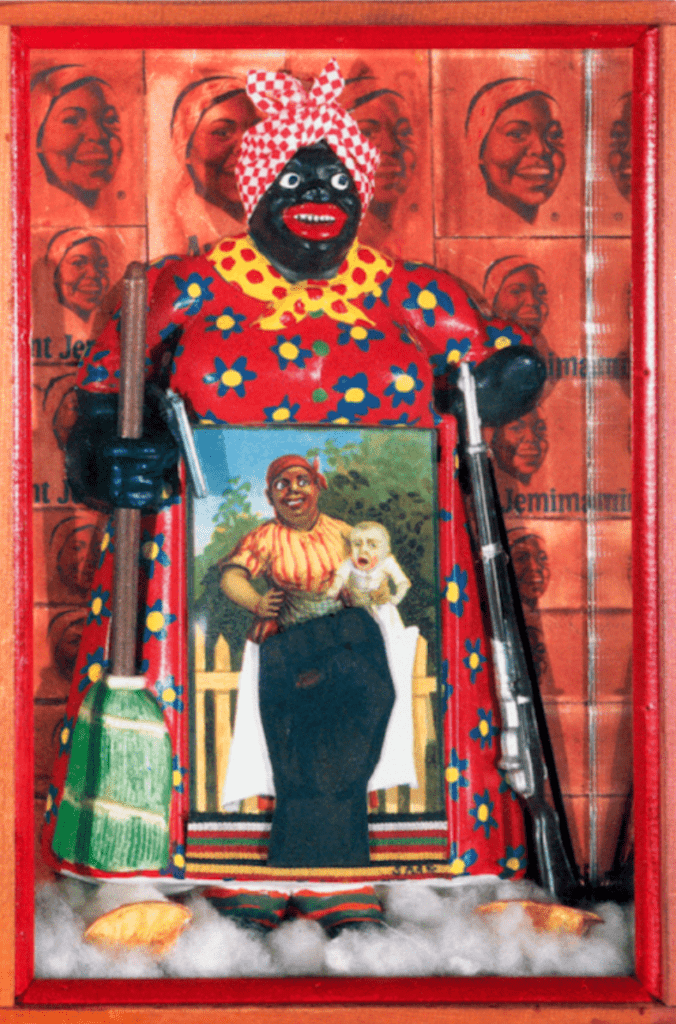

Relying on stereotypes is a theme we have seen in the cultural industry before with artists such as Robert Colescott and Betye Saar using stereotypes in their work as a way of challenging systems of domination. However, these works also evoke nostalgic reminders of a past where domination of the other was profound because the culture of the dominant requires black artists to keep talking and depicting subjects of their experience living in a world where they are dominated.

Another extreme example of mass production can be seen in films that reenact the historical experience of slavery which are released almost every year. These films do not offer any new insight about black culture but instead continue perpetuating images of pain and suffering by re-enacting the trauma of slavery whilst finding ways to capitalize on a community that is already in pain. However, due to a demand for films like this, they are continuously made to satisfy the consumer market. Renato Rosaldo claims that “A mood for nostalgia makes racial domination appear innocent and pure” [8] because it is not via direct contact with the other that the consumer dominates but through consuming a reenactment of what life was like during slavery or colonialism or the Jim Crow era or today’s society. One can sit at the comfort of their homes and look through a screen that takes them to the past to reenact a domination without having to go out their way to physically conquer the other. In Rosaldo’s essay ‘Imperialist Nostalgia’, he explains this yearning where:

Imperialist nostalgia thus revolves around a paradox: a person kills somebody and then mourns their victim. In more attenuated form, someone deliberately alters a form of life and then regrets that things have not remained as they were prior to their intervention. At one more remove, people destroy their environment and then worship nature. In any of its versions, imperialist nostalgia uses a pose of ‘innocent yearning’ both to capture people’s imagination and to conceal its complicity with often brutal domination…Nostalgia is a particularly appropriate emotion to invoke in attempting to establish one’s innocence and at the same time talk about what has been destroyed.[9]

We are walking into movie theatres knowing what to expect from a movie that relives slavery; we witness the continued domination of the other. A theme repeatedly seen in visual arts, a film created over and over again, but still has appeal to the masses because of the nostalgia that it brings to its audience of reminders of a past that is far gone.

Looking back at the wave of primitivism in the nineteenth century art from the paintings of Eugene Delacroix or Paul Gauguin, we can recognize parallels with visual art today. The difference is that the goal is no longer to romanticize the other as the subject but romanticizing the artist’s identity and their experience. As bell hook has argued, in the discursive structure of white culture, the other is deemed to have more life experience than their white counterpart. There is an underlying belief that black people experience life in a very different way (erotic and dangerous) that even in the visual arts when race is not overtly presented as the subject, the viewer profoundly finds a way to go back to it by analysis. What we have to acknowledge is that there is emphasis placed upon showing the pain and suffering of the black community which overshadows celebration of a diverse and beautiful culture. This emphasis creates a resurgence of an essentialist cultural nationalism that perpetuates the stereotypes that are held towards black bodies. As the consumer market continues its demand for works that are political, what results is the black experience becoming an aesthetic that feeds the ever-growing art market. What if we walk into art galleries and museums showcasing work from black artists having thoughts on what to except? Having already placed these artists in a box where expected subjectivity is on race, the only room left for imagination is what new ways or forms in which the dish of racism be served. One cannot see Eghosa’s work for its aesthetics because the assumption is that it must tell the viewer more about the negative effects of racism. I think Eghosa’s work breaks away from the box of social expectations placed on the black artist and this does not mean dismissing that there are issues within this community. There is much more to blackness that transcends subjects of racism and part of the problem with constantly portraying issues without solutions leaves us in the loop of where like the movies about slavery, we are walking into galleries and museums with expectations of specific works on fetishization of black suffering. Turned into a commodity, it no longer has an aesthetic value that can trigger true change but instead becomes like any other product in a capitalist society where subjectivity of difference is exploited and are mass produced with little to no power of challenging social norms.

Art, Sports, and Consumerism

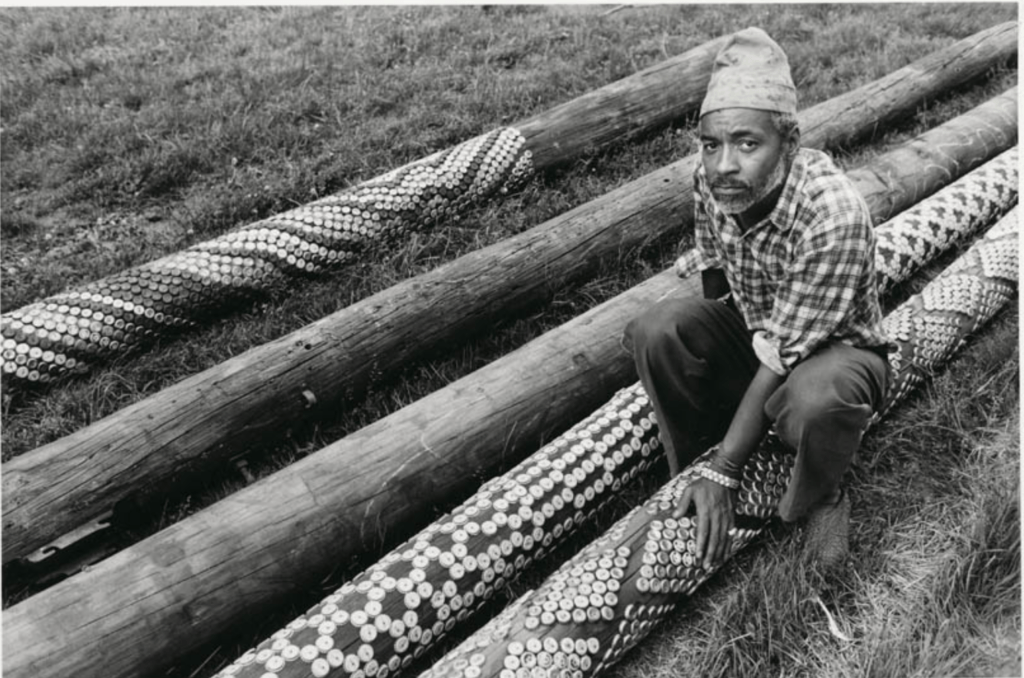

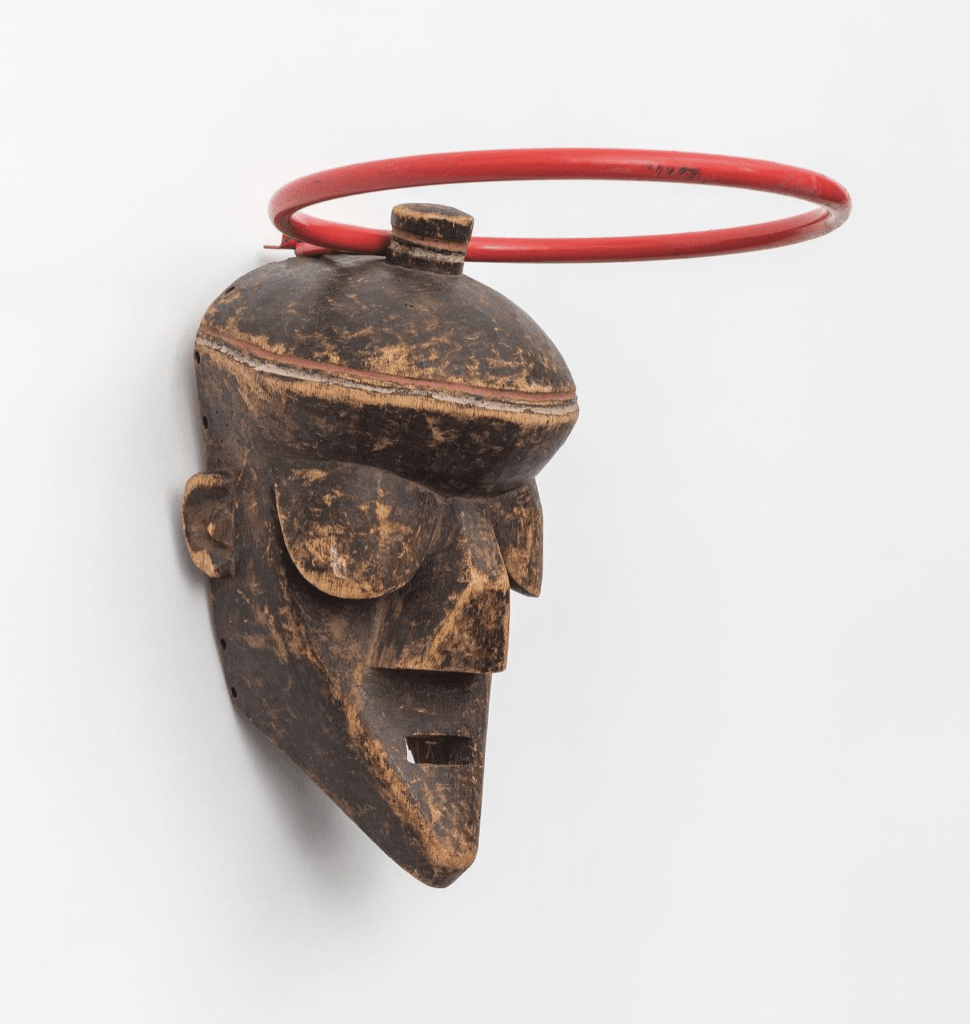

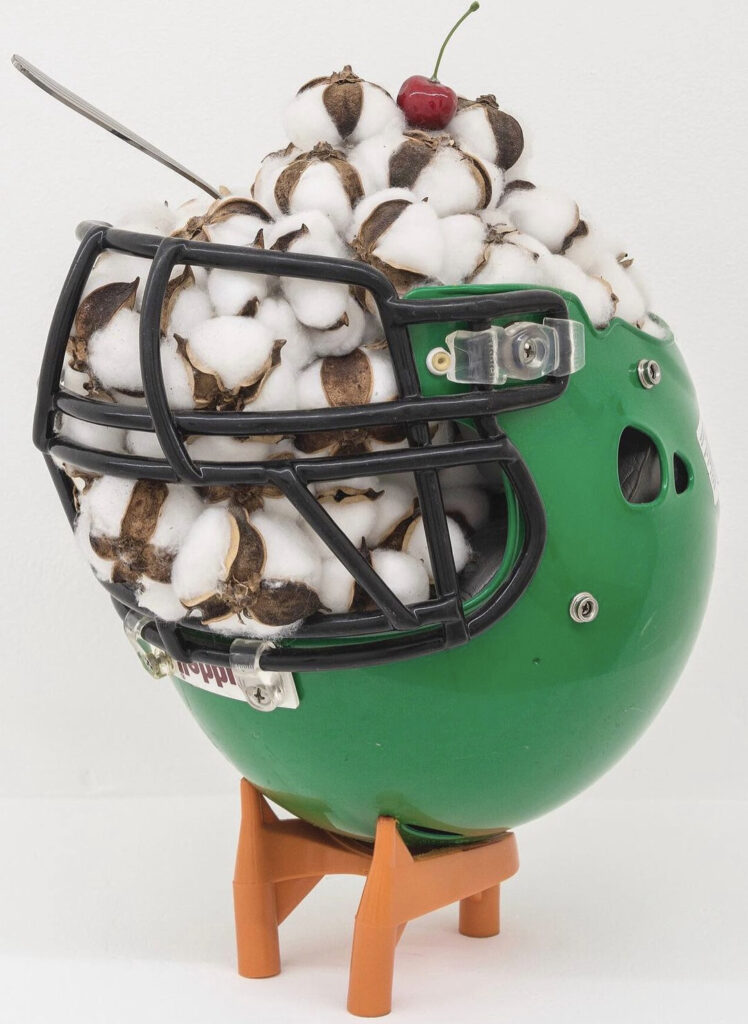

D.C. born artist Emmanuel Massillon primarily works with galleries and museums exhibiting works that he describes as an autobiography on lived experience and representing members of his community. Subjectivity is overtly political with topics ranging from gun violence to gentrification, work that he considers as a mode of creating awareness and preserving history. His practice as a conceptual artist involves the use found objects and carving into them to transform and give them new meaning. Additionally, there is use of visual allegories incorporated in his work to give a symbolic look into the stories about the black experience in America. The symbolic use of imageries is a unique element in work by black artists because “Black people have always been masters of the figurative: saying one thing to mean something quite other has been basic to black survival in oppressive western cultures. This sort of metaphorical literacy, the learning to decipher complex codes, is just about the blackest aspect of the black tradition” [10]. It is in the same spirit that David Hammons stated that “outrageously magical things happen when you mess around with a symbol” [11]. The use of symbols becomes powerful in depicting topics with deeper meaning but also allowing the viewer to digest what is presented to the eye. The challenge for the viewer is to question what is presented to them, one that Massillon mentions in an interview that whenever people see his work, he wants them to question why he made it the way he did as well as their relationship to privilege. In this section, I focus on his works Superbowl Sundae, 2021, Cotton Bowl, 2021, and Inner-City Angels, 2022 that offer a critique on consumer culture within sports. These works were made with the intention of sparking conversation about the current state of our society and its fascination with consuming the pain of black boys. As an influential figure in Massillon’s work, there are parallels with David Hammons’ sculptures that address the ritualistic nature of basketball and football in the African American community. The goal is understanding how fragile the promise of financial liberation inflicts pain on the black boy for mass entertainment hence offering a parallel between sports in today’s contemporary society and slave trade. I also wanted to understand the subjectivity that arises when an artist is emersed in the institution art world and whether work like Massillon’s can provide an effective critique of consumerism.

In terms of the impact of lived experience, both Hammons and Massillon use their life as a reflection of their work with the former having played basketball and the latter football. With the use of ready-mades, Massillon creates visual allegories that question our consumerism of sports and the political consequences of consuming the suffering of the black boy. Hammons’ Higher Goals, 1986, acts as a visual allegory of the impossible aspirations that inner city youth have. “It’s an anti-basketball sculpture. Basketball has become a problem in the black community because kids aren’t getting an education. They’re pawns in someone else’s game. That’s why it’s called Higher Goals. It means you should have higher goals in life than basketball”. [12]

The sculpture contains five poles that are decorated with bottle caps in different pattern variations. Hammons stated that “It takes five to play on a team, but there are thousands who want to play—not everyone will make it, but even if they don’t at least they tried” [13]. The end goal is to make it into the league to achieve financial liberation hence in the work, the hoops are placed on 20” to 30” inch poles to show the difficulty in attaining this dream. Additionally, mass media offers a glimpse of what achieving a pro-athlete status means and creates the lure of living lavish. Capitalism essentially promises that if one works harder, practices mores (pushing the limits of the body) and dedicates themselves to this endeavor, they may break away from poverty. Here the structure of a white supremist capitalist patriarchy creates problems of inequality within which these young individuals exist then introduces a possibility that is eventually beneficial to the same structure through the exploitation of the dreams of inner-city youth hence maintaining the cycle of domination and control.

Twenty-two years later, Hammons made Untitled, 2000 that had the same subject matter as Higher Goals, 1986. The materials used were primarily crystals and glass that represent the fragility of a culture which places athletic performance as its highest pinnacle. It possesses a shrine-like appearance that creates an altar, presumably pointing to the ritualistic nature of basketball and how the emphasis on athletic performance is sacred in the black community. The marriage of symbols offers a visual pun indicating the fragility of the dreams these urban youths hold and how easily they can be broken because in this system, they are means to an end, objects for mass entertainment. A catalogue essay from Phillips Auction adds that “Hammons has recentered the sport of basketball within the frame of consumerism. No longer does his simple visual rhetoric of 1986 apply—where ambition alone was the driving force in the broken dreams of young African Americans, for here it is something far more dangerous: the promise of material wealth resulting from success”.[14] Massillon’s Inner-City Angel, 2022 contains similar symbolism depicting a child size basketball hoop on an African mask, specifically commenting on how early in life this idea is already introduced to the black child where sports become a savior from poverty.

Football represents American imperialism as a nation of domination and conquest as football shows simulated warfare which is followed by a break with advertisements to further consume products. When San Francisco 49ers’ player Colin Kaepernick started sitting and eventually taking the knee during the national anthem before football games commenced in 2016, he was met with heavy criticism for disrespecting the American flag. Although his method of protest was peaceful, the backlash was harsh and numerous Americans utilized social media to show their opinions. Some demonstrating their protest of him by burning jerseys with his name whilst playing the American national anthem. Kaepernick’s peaceful protest was met as anti-American not only for challenging the oppression of black people but doing so in an environment that represents the core identity of America as a white imperialist capitalist society and its power. Demographically, the National Football League has more than 70% players who are people of color and this percentage mainly consists of black men.

Massillon’s Cotton Bowl, 2021 depicts a deflated National Collegiate of Athletic Association football with raw cotton placed on it and a metal spoon in the cotton. He comments, “When looking at the NCAA one can compare their scouting system, unpaid labor, and profit from black bodies to the American slave trade. I placed the spoon inside the bowl to think of cotton as food and a survival mechanism where if a slave or athlete did not perform to the liking of their team/owner, they could be sold or traded”.[15] In Kaepernick’s docuseries titled Colin in Black and White, his experience teaches the viewer of how the scouting system exploits young men. Black men are paraded in front of coaches, most of them white, and like in slave auctions, their physique is scrutinized. They are required to become beasts by a white supremist capitalist patriarchy and the promise it makes is that they will gain material wealth, only and only if, they are act like animals. Hooks contends that:

It is the young black male body that is seen as epitomizing this promise of wilderness, of unlimited physical prowess and unbridled eroticism. It was this black body that was most ‘desired’ for its labor in slavery, and it is this body that is most represented in contemporary popular culture as the body to be watched, imitated, desired, possessed. Rather than a sign of pleasure in daily life outside the realm of consumption, the young black male body is represented as the body in pain.[16]

There is lack of conversation about dominator culture and men do not fully know how to express what this dominating system does to them. A sentiment voiced by Elaine Scarry in her introduction of The Body in Pain, “There is no ordinary language for pain, that it is (more than any other phenomenon) resists verbal objectification”.[17] Lack of language means that these men cannot articulate what they feel hence we become wholly unaware of their pain in chasing the dream of making it into the league. The long hours spent practicing represent the physical torture one must endure hoping that all the pain will eventually pay off. The dominance in form of pressure which couches (mostly white) exact on their players asserts the role of this white supremist capitalist patriarchy. If players are not good enough, or underperform, they can be traded off to other teams similar to how slave trade worked from one slave master to another. On top of that, the players are also taught to see everyone else as competition and using a divide and conquer approach, this structure of domination overpowers the ability to create and foster a community.

In the same year, Massillon made Superbowl Sundae, with experience in playing football from a young age, he talks about how the game was important in teaching desirable virtues. However, the hope remained that if one can make it into the league, they transcend economic hardship. One interesting aspect that Massillon applies is experimenting on the relationship between an object and the viewer, a black person while looking at cotton is reminded of slavery while a white person may see decorations or a raw material for a product. The difference is that today, the black male is compensated for his symbolic enslavement in the league, his pain and suffering are mined to create entertainment for masses of people. Super Bowl Sunday has notoriously been a popular part of American culture, generating more than $10 million in revenue from the exploitation of these individuals. As participants of this American football culture, we are nourished by the pain of black men for our entertainment which is represented by the spoon in Cotton Bowl and Super Bowl Sundae. We become complicit in perpetuating the suffering that black men as viewers but so does the artist in the continued depictions of the variations of pain.

As an artist depicting work that is political, I was also concerned with the extent to which work like Massillon’s can both be a trigger for change but also perpetuate the pain and suffering of the black community. An analysis by hooks voices the same concern where, “Work by black artists that is overtly political and radical is rarely linked to an oppositional political culture. When commodified it is easy for the consumers to ignore political messages. And even though a product articulates narratives of coming to political consciousness, it also exploits stereotypes and essentialist notions of blackness”.[18] When freedom in the context of breaking away from poverty is introduced, one can also compare the aspiring athlete to the artist. Financial freedom can be achieved from producing works in the cultural marketplace; however, the tradeoff becomes perpetuating stereotypes ascribed to the black community. In an interview with Massillon, we explored his thoughts on the cultural marketplace:

I grew up seeing a lot of pain and anguish in my community. Then I was introduced to a new world in the art world where life is very different. So, I think it is my duty as a black artist to talk about where I come from, which is why I have to come back to the issues within my community where there is too much pain to ignore. If you are a black artist and are not talking about these issues in a way, it is a disservice to our community. We go to white schools and see white artists who get to be simpler, who explore working purely with line, shape and form and the beauty of something without having to be political. Additionally, the art market does have a demand for black artists as a way of making up for years when we were excluded but it is also as a way them to show it that it is diversity and inclusion of the other.[19]

Overall, Massillon’s artistic practice as a critique to systems of domination uses visual language in challenging our relationships to different objects. However, it is for the same reason that he states that we have different relationships to objects that I think further analysis is required for the viewer to gain awareness of what they are viewing. Furthermore, this critique can only be effective when the viewer understands that objects from the point of view of the artist.

Afro-futurism and the Yarn for Utopia

As black artists, we find ourselves in a very paradoxical situation. One has to choose between two routes, one that will tackle head on the reality which black people live in or creating a way to move from this reality and create a haven. With many people wanting to show realism, we tend to be stuck in a phase of theorizing change but never finding ways for praxis to occur. The hostility of existence lies in the fact that no black person in America feels safe because blackness is deemed as the personification crime or violence. From the clutching of bags to the calling of police on a black man simply walking in a park, these are reminders that the black body is not quite safe in spaces. There is a looming fear, whether acknowledged or not that something could go wrong at any given moment. Additionally, circulation of news about the dangers befalling black individuals bombards the senses to a point where desensitization occurs. In “A Narrative of Resistance in the Face of Stasis” by Raimi Gbadamosi, he analyzes what this does to the spectator. He adds,

These contemporary killings and maiming, of which there are too many to easily list, are a public reminder that Black life remains perilous in the face of the promise of some better day. What this means is that Black life in all its forms has to remain vigilant of disaster lying in wait of which textbook defenses might not prove suitable against. Remaining in a constant state of fight or flight has destructive consequences on the ability to live a complete life, not disturbed by existential fears, preferably geared towards a desirable and productive future. [20]

One must calculate how to navigate life to avoid this fate that black people in America are subjected to. The reality is, living in constant fear paralyzes the individual. The promise of a better life becomes empty and when we recognize the same pattern constantly repeated, a nihilist attitude becomes the new reality. No matter what one does, breaking away from this system is an impossible task because from the start, one is destined to have all working against them. What does it mean for black people to see one of them constantly killed in the media? A message is sent, and one registers that they are not safe both in the public or private spheres. Evident from state sanctioned executions such as Breanna Taylor’s which is great example of how even in the privacy of one’s home, one is still in harm’s way. George Floyd’s public execution that many of us watched through our screens. There are many others who have been murdered owing to the fact that our society operates on the basis of domination of the other. Afrofuturism then must act as an antithesis of the current white supremist capitalist patriarchal culture to avoid being sucked into the cycle that other movements of liberation tend to fall into. The further Afrofuturism is able to move from this market-dominated vision of culture, the more autonomously it can help represent an alternate future that fulfills the promise of a better life. What Afrofuturism requires from us is to go against the status quo and imagine a world beyond one’s mental prison and systems we are born into by asking “what if” questions. Marcuse states in Reasons and Revolution that “The revolution requires the maturity of many forces, but the greatest among them is the subjective force, namely, the revolutionary class itself. The realization of freedom and reason require the free rationality of those who achieve it”.[21] Moving from a market-dominated world is confronting the reality that blackness or otherness is commodified in today’s cultural marketplace not because it offers an insight to the lives of those dominated in our culture but because the structure of oppression allows for exploitation of otherness while promising material compensation.

Although it is necessary for us to see the world as it is, we can only imagine new worlds where we are truly free in stories or art which in turn trigger us to envision this future to make it a reality. Social problems are multifaced and whenever we start somewhere, one issue tends to lead to another, indicating how the roots of a white supremist capitalist patriarchy are deeply interwoven in our society that we seem to be dancing around the same issues and never moving forward to actualize significant. The constant cycle (especially social justice movements) is that an event occurs that triggers the want for change, we advocate (mostly through social media), we protest, we buy items to show symbolic solidarity, then we go back home and proceed with normality because we confuse movement with progress. This confusion is the same trap that prevents social movements from progressing to the point where true change occurs. A good example is the Black Lives Movement, one that is supposed to spearhead the movement towards liberation but commonly ends up as a hashtag for social appeal or words on a t-shirt. An event occurs where we notice that there is a problem with how we are living, we see the need to change, we start the process but somehow fall into the traps of capitalism. This is partly because in theory understand our reality, but it takes work and radical change to move forward, however, we are already overworked and alienated under this system leaving little time to no time to create change. Consumerism finds a way to tiptoe into a movement, completely hijacking what it is meant to do in the first place. Here, the use of lessons from the past and present are used to inform Afrofuturism which makes a promise of freedom and liberation where instead of turning to escapism for a quick fix of running away from our problems, we turn to imagining possibilities for future realities.

As previously mentioned at the beginning of this essay, Afrofuturism needs both the writer and artist, but most importantly, it requires both to be critically aware of the cultural marketplace. Society is structured for the consumption of visual images than words in books and articles hence the artist holds an important role in depicting an Afrofuturistic imagination. Nigerian born artist Sam Onche and I took this opportunity to work together to give a framework how we speculate the future as. With both of us having been born and raised Africa, we were participants of the oral traditions passed down from one generation to another many of which had elements of Afrofuturism such as magic and superstition. In an interview titled “Talking with Ben Okri”, he says:

I was told stories; we were all told stories as kids in Nigeria. We had to tell stories that would keep one another interested, and you weren’t allowed to tell stories that everybody else knew. You had to dream up new ones. And it never occurred to us that those stories contained a unique worldview. It’s very much like a river that runs through your backyard. It’s always there. It never occurs to you to take a photograph or to seek its mythology. It’s just there; it runs in your veins; it runs in your spirit.[22]

Comparing this to using the imagination, the use of stories is important as we look into future possibilities and one that the viewer/reader should be a participant of.

At the beginning of my interview with Onche, he introduced his art practice; “Most of the time, even with a sketch, I normally end up with something different from what I thought I wanted the result to look like. When I am creating, I let my mind roam in a way that I truly find hard to describe myself but at this time, creativity runs its course”.[23] I found myself thinking of the description that romantic poet William Blake gave to the imagination. Describing it as the process by which as we perceive objects, our thoughts and feelings blend in with them and they become expressive of our inner life. This process goes on spontaneously and constantly that through it, experience acquires a heightened vividness and significance that amounts to an increased fullness of life. [24] Onche attributes his creative influences to music, movies, and comics especially those with heroes or characters with supernatural abilities and technical advancements. Onche’s paintings display his experimental use of colors while the characters created seem to have gone through the process of evolution to make a techno-human. He attributes this collaboration of human and machine to his idea of the black body as a machine that has been able to withstand slavery, colonialism and other forms of domination but persist. Onche’s choice of subjectivity in his work is to offer a perspective where black people can see themselves in a futuristic environment. One of the sentiments both Onche and I shared was our mutual understanding of the demands that the art world makes when it comes to subjectivity of black artists with Onche commenting: “If I wanted to be on CNN, I know the exact type of work that I have to make to gain recognition”.[25] In The Black Person in Art Jerry W. Ward Jr. writes:

“Young writers seem always tempted to follow what is popular and profitable. The real danger is that a growing number of young black writers may not be willing to do the hard work that precedes depicting ‘the truth about themselves and their social class. The heroic young writer will study Afrocentric and Eurocentric histories, languages, African and African American orature and literature, political economy, and psychology; they will study works by such responsible black artists as Fredrick Douglass, Langston Hughes, Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, etc. Only then will they be prepared to write the truth about themselves, the Other, and race/class enigma. Only then will the young writers resist the temptation to pander”.[26]

The same applies to the artist, it is through educating ourselves that we can provide substantial critiques of structures of domination without falling into the lure of capitalism.

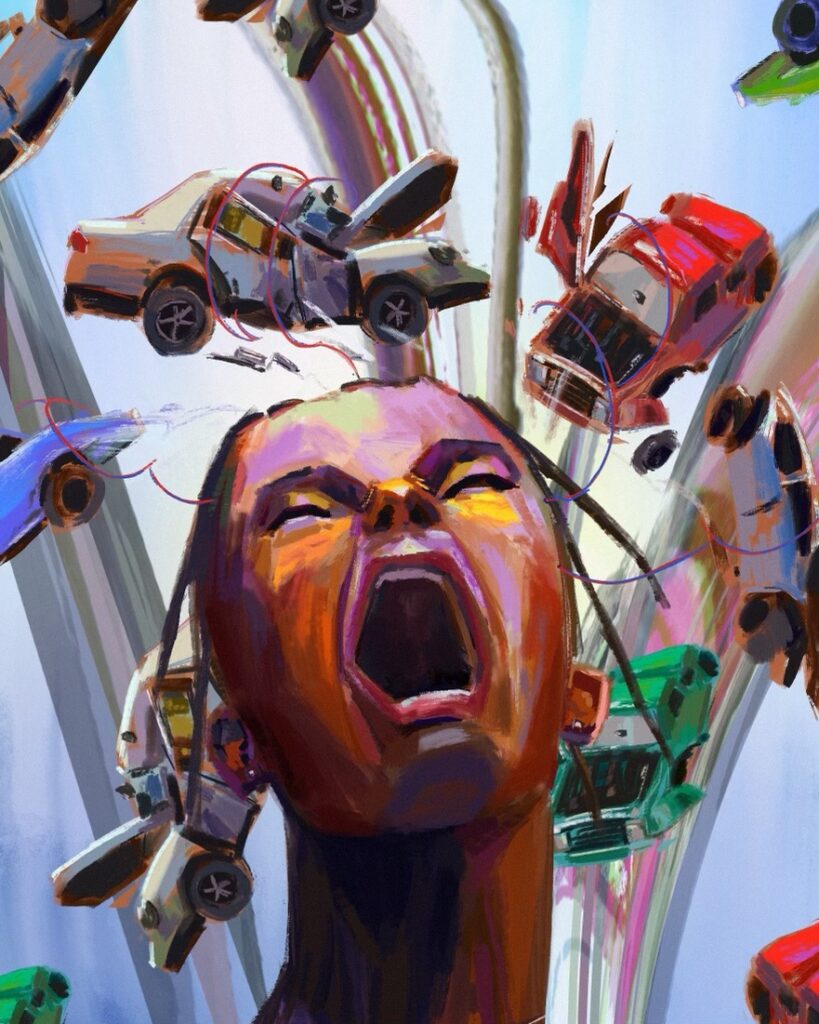

Japanese cyberpunk films have also been a great place to look at when we imagine the future as they explore the possibilities of what happens when machine and human make interactions. One of Onche’s work is inspired by Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira which explores the subject of pain and power. The protagonist Tetsuo lives in Neo-Tokyo where he gains psychic powers but because of the pain he holds from his past, he is unable to control his powers and instead becomes destructive to everyone living in the city.

Onche’s painting Scream, 2022 depicts a black body immersed in a techno-environment and pain is clearly shown in the expression in the face as they let out a scream. This goes back to the question posed to Samuel Delaney on looking to the other as a source of freedom. What happens when a body in pain is given power? How can we look to black individuals to lead us into a future where we explore possibilities of freedom if we cannot talk about this pain without it ending up as a commodified product in a capitalist system?

Imagining our possible future, we must push our theories beyond just thinking and moving into practice by learning what works and what doesn’t. Artists working within the institutional art world should use visual language as well as utilizing writers as the bridge between their work and the audience to make critiques that educate and hold us accountable. We must admit that there is a problem with society’s appeal to dominate the other in the subtle ways that exist in mass media. Mainstream media creates an appeal where one’s online persona has to have certain characteristics like being inclusive and progressive for general acceptance without doing the radical work of educating oneself. Commodification becomes even more innocent because relating to black culture is a way of proving that one is not racist and supporting the Black Lives Movement via a tweet proves that one is among the good ones. A symbolic performance seen in 2020 was an online movement of adding black squares was a sign of solidarity to blackness. Being ‘woke’ is proof that one is a well-wishing individual who separates themselves from the racist ones. What mass media offers is a chance at admission as a participant of blackness via consumerism of cultural products. It also immerses one into black culture for its fruits while distancing them from the actual problems of this community. What I fear for the black artist is the ground where we continue to perpetuate the problems in our community because the art world also promises material compensation for making specific products. The promise of recognition is one that drives the production of stereotypical images of a racist past that invokes nostalgia for a dominating class. Walter Mosley states that “the limitation is imputed reality of race as an axis of social stratification, which is compounded by the expectation that African American literature should address this reality. The task of cataloguing the horrors of actually existing racism has confined African American writers to realist literary genres and discouraged them from envisioning alternate future”.[27] This sentiment also applies to the artist whereby depicting realism stands in the way of imagining what is possible.

An alternate future in Afrofuturism is the formation of communities that are based on us being emotionally knowledgeable on the topic of love. As alienated laborers, work has been at the center of our lives, and very little time is left to contemplate on the systems that we are born into. Capitalism works so well because it offers us a distraction (mass media and consumerism of products) and after a long day at work, nobody wants to go back home and theorize on ways that capitalism does not work, and this very reason is why I think capitalism works so well. It creates the illusion that we have freedom to do as we want, that we are better because we are not like peasants in the feudal system or slaves plowing the fields. Looking to the future, I think educating ourselves on the politics of consumerism will result in understanding the relationship between the dominator and the dominated to create both class and race consciousness. Herbert Marcuse also argued for working from within the institutions by creating counter-institutions that transcend capitalist dominative logics. Hence the black artist must work within the confines of capitalism by aligning themselves with Afrofuturism. As we imagine a possible future, we move toward building communities of love and moving away from communities of domination. Here is where we must resist the delight of consumerism and take time to self-reflect on our emotional wellbeing. By building communities of love and mutual understanding, we establish a world where we have an attitude of well-being for ourselves, relatedness to others and our planet. The promise that Afrofuturism makes is one of imagining what change you want and working to actualize it by building a community with the lessons from the past and present.

Primrose Paul is an artist and curator currently pursing her BFA in studio art at the University of Indianapolis.

Notes

- Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future.”Flame Wars, 1994, 179–222. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822396765-010.

- Okoro, Dike. “Futuristic Themes and Science Fiction in Modern African Literature.”Futurism and the African Imagination, 2021, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003179146-1.

- Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future.”Flame Wars, 1994, 179–222. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822396765-010.

- hooks, bell.“Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” Black looks: Race and representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Interview with Omoruyi Eghosa.

- Interview with Omoruyi Eghosa.

- hooks, bell.“Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” Black looks: Race and representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.”Representations 26 (1989): 107. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928525.

- Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.”Representations 26 (1989): 108. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928525.

- Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future.”Flame Wars, 1994, 185. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822396765-010.

- “David Hammons: MoMa.” The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.moma.org/artists/2486#publications.

- “David Hammons – Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York Monday, November 11, 2013.” Phillips. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.phillips.com/detail/DAVID-HAMMONS/NY010713/7.

- “Higher Goals.” Public Art Fund. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.publicartfund.org/exhibitions/view/higher-goals/.

- “David Hammons – Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York Monday, November 11, 2013.” Phillips. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.phillips.com/detail/DAVID-HAMMONS/NY010713/7.

- Comment from Emmanuel Massillon.

- hooks, bell.“Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” Black looks: Race and representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Scarry, Elaine.The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- hooks, bell.“Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” Black looks: Race and representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Interview with Emmanuel Massillon.

- Gbadamosi, Raimi. “A Narrative of Resistance in the Face of Stasis.”Futurism and the African Imagination, 2021, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003179146-3.

- Marcuse, Herbert.Reason and revolution: Hegel and the rise of Social Theory. London, 1941.

- Okoro, Dike. “Futuristic Themes and Science Fiction in Modern African Literature.”Futurism and the African Imagination, 2021, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003179146-1.

- Interview with Sam Onche.

- Perkins, David. “William Blake.” Essay. InEnglish Romantic Writers, 42. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Publishing, 1995.

- Interview with Sam Onche.

- Gates, Henry Louis. “The Black Person in Art: How Should S/He Be Portrayed? (Part II).”Black American Literature Forum21, no. 3 (1987): 317–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2904034.

- Jackson, Sandra, Julie E. Moody-Freeman, and Madhu Dubey. “The Future of Race in Afro-Futurist Fiction.” Essay. InThe Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism and the Speculative. New York: Peter Lang, 2011.

Bibliography

“David Hammons – Contemporary Art Evening Sale New York Monday, November 11,

2013.” Phillips. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.phillips.com/detail/DAVID-

HAMMONS/NY010713/7.

“David Hammons: MoMa.” The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed May 16, 2023.

https://www.moma.org/artists/2486#publications.

Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future.” Flame Wars, 1994, 179–222.

https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822396765-010.

Gates, Henry Louis. “The Black Person in Art: How Should S/He Be Portrayed? (Part

II).” Black American Literature Forum 21, no. 3 (1987): 317–32.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2904034.

Gbadamosi, Raimi. “A Narrative of Resistance in the Face of Stasis.” Futurism and the

African Imagination, 2021, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003179146-3.

Marcuse, Herbert. Reason and revolution: Hegel and the rise of Social Theory. London,

“Higher Goals.” Public Art Fund. Accessed May 16, 2023.

https://www.publicartfund.org/exhibitions/view/higher-goals/.

hooks, bell. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” Black looks: Race and

representation. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Okoro, Dike. “Futuristic Themes and Science Fiction in Modern African

Literature.” Futurism and the African Imagination, 2021, 3–16.

Perkins, David. “William Blake.” Essay. In English Romantic Writers, 42. Boston, MA:

Wadsworth Publishing, 1995.

Jackson, Sandra, Julie E. Moody-Freeman, and Madhu Dubey. “The Future of Race in

Afro-Futurist Fiction.” Essay. In The Black Imagination: Science Fiction, Futurism and the Speculative. New York: Peter Lang, 2011.

Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.” Representations 26 (1989): 107.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2928525.

Scarry, Elaine. The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world. New York:

Oxford University Press, 2006.