Interview with the Million Artist Movement

Laura Thompson

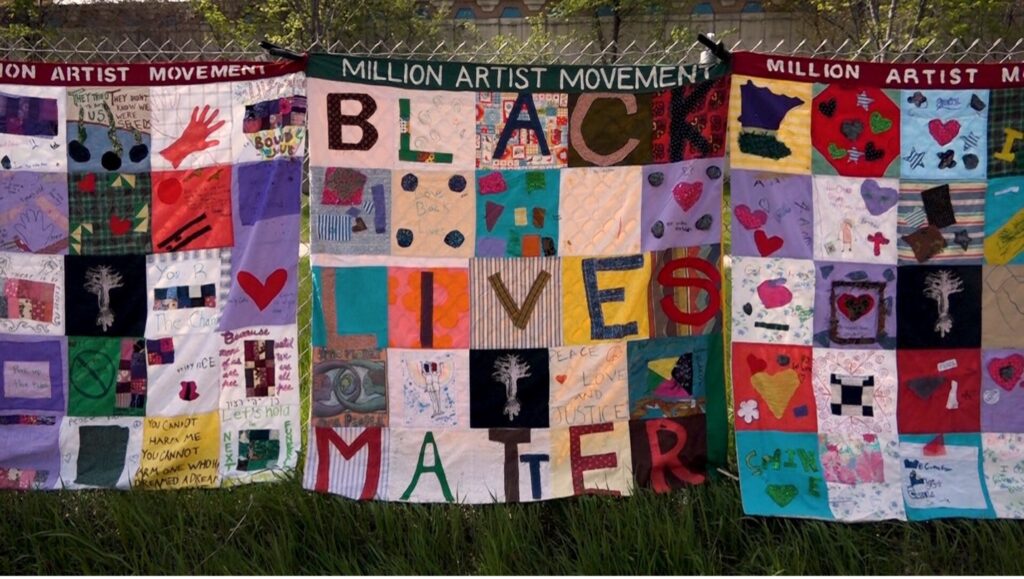

The Million Artist Movement (MAM) is an organization based in Minneapolis, MN that believes in the role of art in the campaign to dismantle oppressive racist systems against Black, Brown, Indigenous and disenfranchised peoples. They are focused on community engagement projects like quilt fabrication, food cultivation and distribution, and educational initiatives. The following interview was conducted in the Fall of 2021 between MAM lead organizers including Maria Asp, Alizarin Menninga, Paige Reynolds, Laura Hill, and FIELD editorial collective member Laura Thompson.

Laura Thompson: Could you talk about the origins of the Million Artist Movement? How did the organization get started? What were your goals in the beginning? And how have those goals shifted over time?

Maria Asp: We started gathering in 2014 during everything that was happening in Ferguson [Missouri] and our first event was on December 13, 2014. We had many, many, many meetings before that, to figure out what our role would be, who we were, and our messaging. I think that we were asking ourselves what the intersection of art and politics is and how does art function alongside the uprising. We were modeling ourselves after the work of the Black Arts Movement and made sure that there was always a combination of political education, study, and an aesthetic component. We believe everyone is an artist and believe that art making helps connect us and helps us question and expose what’s happening in the world. It was at our very first event when we started our Power Tree Quilts. There we were, at the government center, lugging boxes of fabric. We learned a lot on how to pare it down. But we always wanted to make sure that we’re putting ourselves in a place of being able to create together.

Alizarin Menninga: Some notable things that have developed in just the past year or two have been: registering formally as a cooperative organization and deciding and voting with all of the folks who have been part of MAM. Most folks since 2014—who Maria was talking about—are definitely growing as well. Since then, we have been partnering with many other sister organizations and formations. We have grown to have a board with a membership and with the annual meeting for our stewards. The programming has also definitely expanded too since 2014.

Paige Reynolds: I am a more recent member. Although now it’s been a few years, but I wasn’t there at the very beginning. But I can see in some ways that it has evolved. I mean, MAM seems to have always been intergenerational, but I think some of the programming that’s just for kids has expanded as a way to help them make sense of what’s going on because of all the injustice in the world or the inequality. They witness it and they feel it in their bodies too. So, we are giving them an outlet. Also, some of the artists within the Million Artist Movement want to develop their skills on the community organizing side of their practice or want to know what it’s like to lead a power gathering or lead others in political education.

LT: Thank you so much for that insight into the development of MAM. Something that I am curious about is your organization’s focus on the hand and the tangible, like the Power Tree Quilt and your project based around food sovereignty. In these projects, it seems like you are using engagement with material or with the land as a way to access or develop community. Do you think that will continue to be a focus for MAM?

Alizarin Menninga: It’s been an adaptation this past year to move to doing a lot of virtual meetings. It’s been really lovely because like other groups who have adapted, we’ve been able to send full kits to different locations for programming or individuals, which can form a community space for people to have a hands-on element. We were just watching an art co-op lecture and they were talking about the power of disembodiment and alienation from our experience and our work and the natural world and touching things that we create and surround ourselves with. So, yes, I think having the entire means of production being hands-on and giving this opportunity to both our stewards and people who we pass by on the street who want to participate is important.

Maria Asp: I would just add in that it’s that disconnection, that dehumanization, that we’re working against. I mean, I’m sitting right here, knitting. We spent a lot of time pre-COVID at [Thelma] Battle Buckner’s Piece-by-Piece Quilt Shop, where she’s literally teaching the community how to sew. I’ll never forget, there were these teenage girls that were getting kind of rowdy in there and she just threw it down. She said, every single day you put on clothes that somebody else made, you ought to be able to respect that. And so, we’re trying to reconnect all of those labors, and a lot of labor is invisible or is on some bizarre hierarchy that is just made up by somebody. So, we’re always curious and eager to can our own food and grow our own food and drive tomato seedlings to each other. During COVID, when we would find one of our community members was sick, we would show up at their house with soup and a tincture that Paige makes and take care of each other. And that extends to all the areas we want to be connected in a time of disconnection.

Paige Reynolds: I think what’s coming to mind for me and something that we talk about a lot is the toil of our everyday lives, especially the things that may be traumatizing or stressful or anxiety inducing and disconnect us from our bodies. We can also get disconnected from our imaginations, and I think the way that we connect with the land, with plants and relatives helps us to get back into our bodies and back into our imaginations and we really need those in order to build systems that work better for everybody to dismantle the things that are oppressing us. Without that imagination piece, we’re just going to end up recreating the same thing. So, I see the land as playing a big role in that and the many lessons that the land has to teach us helps to stir that imagination and get us thinking about different ways of being.

LT: You mentioned Thelma Buckner and the Piece-by-Piece Quilt Shop that you started to work with in 2014. How did that collaboration develop?

Maria Asp: Well, Thelma is no longer with us. She is an ancestor, but she is a huge presence in our community. Her family had a church before [highway] 94 was there in the Rondo neighborhood. [1] She raised eight kids on her own, that are all musicians and active community members. So, when we decided to start with quilting, it was one of our members who said we’ve got to get Thelma involved. And so, Thelma gave us all the fabric and really, she gave us the tools and the place to sew them together. She was a huge, huge part of the beginning and the continuation of the Power Tree Quilt.

LT: The quilts are a great example of a community project in how they are made and used. They are also working on many different levels, drawing from histories of resistance and memory, functioning as gifts for grieving families, and as protest banners. It seems like a lot of people can easily connect with them.

Laura Hill: It’s very accessible and it’s so easy that anyone can do it: from us to a little child to an elder. I think what’s so nice about it, is that it’s so open. There’s not a right or a wrong way to do it. I love watching what emerges, because some folks will sit down and they’ll spend hours sitting and working on something or they’ll want to take it home and keep working on it. Then other people know right away when they sit down what they’re going to create. When we were painting ours during an event the other day, this kid—who had to be two or three—started drawing these hearts, and it was gorgeous. I mean, the whole thing was just full of hearts. And it was that simple, but when you start to piece all the things together, that’s what I think makes it complete. I mean they’re all beautiful standalone pieces, but I think what makes it powerful is that they’ve become woven together and then there’s the meaning of what that person put into it. Then the larger meaning emerges, and you don’t always know what’s going to emerge when you start, because some people think we have a plan for each quilt. But they really don’t. They just come out of each event and each interaction. And you can tell how much care and love people put into them. This weekend, I did an impromptu quilting thing. Some people were sewing buttons on their fabric scraps and then other people were drawing things. I don’t think you have to be a [trained] artist, but I think we really try to encourage everyone to see themselves as an artist. So, I would say it’s very accessible. Maria and Alice just redid our quilting books, and I think they are really helpful for people to understand the purpose. Seeing other people’s quilts helps make it accessible because they see the variety.

LT: You are talking a lot about events that MAM puts on. Do you see MAM members functioning as facilitators to bring people together?

Maria Asp: When we’re doing the community art making, we are definitely facilitating. And just like what Laura [Hill] said, every quilt square becomes a story and a relationship and a connection. When we were at the George Floyd Remembrance, a man sat down and talked to us for a long time. He was a good friend of George Floyd’s. He told us that George had protected him. This man had been trapped in the incarceration system for many years. He ended up showing us his stomach where he had been shot—it was a very emotional and intense conversation. His square is very simple, yet complex. It’s the whole interaction that happened. Every time I look at that square, I think about that man. Sydney and I sat with him for a long time. If we didn’t have the invitation to create, I don’t know if that connection would have been made. So, in those instances, we are facilitating, and we deeply listen to what people tell us with their words and what they show us with what they’re making in their square. We’re forming a connection there. Through the political education and sewing sessions that Elizabeth was talking about when COVID hit, we turned that into a virtual get together. But like this weekend, we’re doing a two-day intense study of Indigenous and Black solidarity.

Paige Reynolds: Even with the political education, a lot of us are rooted in a certain perspective. We’ve read books like Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and things like that. A lot of what we’re doing isn’t just talking at people or prescriptive or instructive. It’s also the discussion and the art making that helps people bring out their own life experiences and talk about that and get to see each other on a deeper level. Talking about their own experiences with different systems of oppression and talking about their own identities or their own resilience and coming to new conclusions or having new ideas from hearing others talk about themselves is generative. We do these boot camps, a lot of time where we’re reading something together and talking about it. Or even if there’s something that’s more like a lecture-style gathering, there’s always discussion, or we may be doing coursework as well… We cultivate space for people.

LT: Lastly, where do you think that the Million Artist Movement is heading, where would you like to see this organization go in the future?

Laura Hill: I think we’re going to lean more into our cooperative values. We’ve learned a lot about being a co-op and what that means. And I think COVID has allowed some of us to see that there’s multiple ways for us to provide art making and growing. There are multiple ways for us to provide art making and food cultivation to take care of each other. It isn’t that we weren’t doing that before, but it pushed it to another level for some folks, where they found spaces for themselves. Things that we were dreaming of actually came into being, like Rock Springs and other co-ops and formations. We’ve seeded a lot of things. MAM has provided a very fertile ground for people to grow these really incredible anti-colonial, radical movements…We don’t want to replicate systems of oppression. We don’t want to replicate the nonprofit industrial complex. We want to be an organism that continues to be able to be responsive to what this community needs. We have a strategy, a pedagogy, and a political education that grounds us in our beliefs. In this way, we work toward actualizing some of the dreams we’ve talked about.

Paige Reynolds: Something that we constantly talk about and dream about is how to support our community stewards and how can we support their work: as artists, as community members, as cultural workers. How can we show up for them? How can we support them and how can we provide opportunities for them to share what they’re doing with the community to develop their skills. I’m excited to see how much further we can take that with a co-op structure. A lot of the time when it comes to the arts, people don’t want to talk about money, but artists need money to eat and to pay rent and provide real, tangible resources. We have a reparations fund for Black artists in Minnesota that is just given, and you do whatever you need or want to do with it. That’s why it’s called Trust Black People.

Laura Thompson is a Ph.D. student in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the University of California, San Diego and a member of FIELD’s editorial collective.

Notes:

[1] The Rondo neighborhood was central to St. Paul’s African-American community in the 1930s. By the late 1950s, this residential and business center was devastated by the construction of Interstate 94. See: “Rondo Neighborhood & I-94,” Minnesota Historical Society Library, https://libguides.mnhs.org/rondo.