The UCSD Community Stations: A Bioregional Infrastructure for Ecosocial Justice

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman

UCSD Center on Global Justice

We were honored to celebrate the work of Newton and Helen Harrison at the Listening to the Web of Life symposium early in 2022. [1] Little did we all know then that it would be the last time we connected with Newton. Helen and Newton were always a great inspiration for our research-based practice. They presented a model of art practice that integrated art, ecological systems, politics, public culture and ecosocial activism across scales. As an artistic practice, they showed all of us that we need to get out in front of ecosocial crises—that art cannot arrive at the end of a process to simply decorate society’s mistakes, or to see itself trivialized by scientific “expertise”. Art can join forces with science, to expose and illuminate, and to redirect collective will. No wonder Newton chose force majeure to describe his last project. The ecological turn in art today is unimaginable without the pathways the Harrisons forged.

Border crossing

In honor of their inspiration, we shared our research-based ecosocial and spatial practice, embedded at the San Diego-Tijuana border.[2] We see this zone as a microcosm of all the injustices and indignities experienced by vulnerable people across the globe: political violence, climate disruption, accelerating migration, rising nationalism, border-building everywhere, deepening inequality and the steady decay of public thinking. We live and work a few miles from the child detention centers that will forever stain this period of American history. San Diego-Tijuana has become a lightning rod for American nativism. And though the news cameras are gone tens of thousands of Central American migrants wait at the wall for asylum that never comes, reviled by the Mexican public as a nuisance, an “infestation”. Or else they sit in U.S. detention centers as tools of deterrence and exposed to a raging pandemic. It has been particularly devastating in recent years to witness the emotional impact on children, their fear and the inevitable psychic internalization of being socially and morally marginalized. Hopefully there is relief on the horizon. But the prospect of more border porosity in the coming period is drawing even more people north. With misinformation circulating on social media, conditions are intensifying every day. And climate change will inevitably accelerate these flows in the years to come. A recent United Nations survey found that 72% of arriving migrants at our southern border are agricultural workers, and that agricultural instability was a major factor in their decision to walk north. Global injustice is an intensely local experience here.

Against these local atrocities, border communities and activists on both sides of the wall continue to confront and productively circumvent unjust power. Some of this contestation is about sanctuary and protecting people targeted by the state. Some of it involves working through the courts, the detention centers, and other institutions of power to advocate for people ensnared in the net of political violence. Some of it takes the shape of bottom-up civic agency that exposes and counters unjust power, confronts hateful political narratives, and transgresses boundaries. Much of it arises informally through everyday collective practices of adaptation and resilience in conditions of scarcity and danger. Over the years we have accompanied some of these bottom-up emancipatory transgressions, and irruptions of democratic will, in close partnership with agencies at the front lines. In recent years these struggles have also attracted artists and cultural producers form around the world to engage in acts of performative protest. But we have been mostly critical of this uptick in ephemeral cultural actions that dip in and out of the conflict. They tend to be extractive in their processes; and their impacts on public consciousness as fleeting as the Instagram posts they generate. What happens the day after the happening?

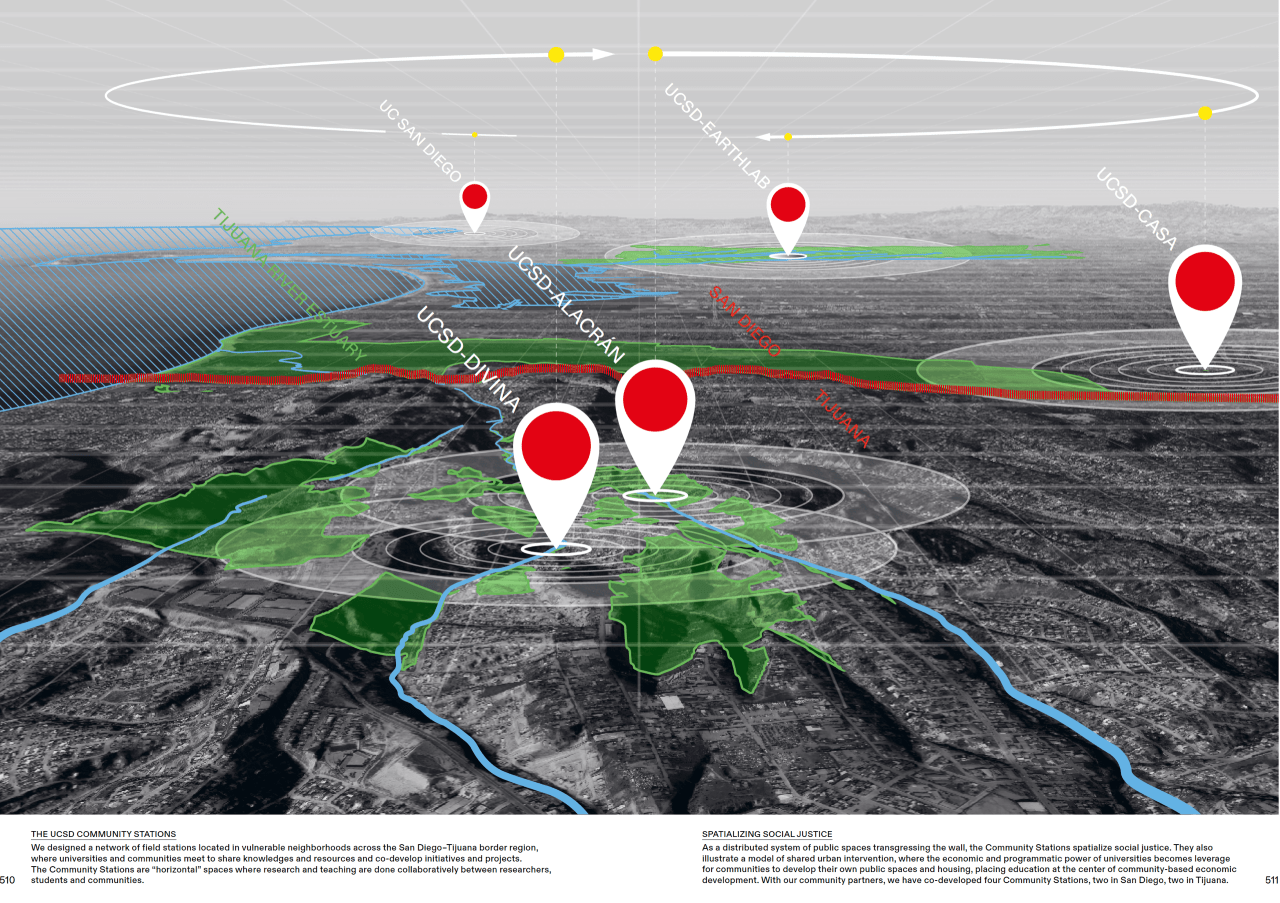

Instead, we advocate for a longer view of resistance, a more systemic approach to the drivers of injustice, and more strategic thinking about cultural, institutional and spatial transformation in the border region. These commitments have culminated in a project that we shared at the Web of Life event, the UCSD Community Stations. The Community Stations are a network of public spaces located in vulnerable neighborhoods across the border region where universities and communities meet to share knowledges and resources, and collaborate on research, dialogue, cultural and educational activities, and urban design-build projects in the city. The Community Stations are the field-based social engagement arm of our research-based design lab inside the University.

In this work, we localize the global: We have always resisted the idea that global justice is something that happens “out there” in the world somewhere. Living and working where we do, we don’t need to travel far to engage territorial conflict, migration, poverty and climate justice. We are minutes away from an international border in crisis, and this enables an amazing proximity between studio and field, between theory and practice—what we think of as a critical proximity. Of course going local here means recognizing ourselves as a region. A site of interdependence. Despite the wall and ugly political rhetoric designed to divide us, we are a binational ecology of flows and circulation, and our future is intertwined. Air, water, waste, health, culture, money, hope, love—these things don’t stop at walls.

Through the Community Stations we are committed to building a cross-border citizenship culture, a sense of belonging that is defined not by the nation-state or the documents in one’s pocket, but by shared interests and aspirations among people who inhabit a violently—and artificially—disrupted civic space. Those who benefit from narratives of separation and mistrust prefer that we remain a fragmented public, that the idea of citizenship divides rather than unites. We seek to inspire more inclusive imaginaries of co-existence and cross-border citizenship in this contested territory. Rethinking public space as the site for constructing a new civic imagination is the main challenge. We reject conventional strategies of urban beautification and innovation that turn our public spaces into sites of leisure and consumption. We believe public space must be a site of dialogue and contestation, and infused with resources and tools to increase public knowledge and community capacity for political and environmental action.

The Community Station Sites

For us, then ecosocial justice is a distributive concept: Requiring not only the re-distribution of resources but also the re-distribution of knowledges. We designed this reciprocal knowledge infrastructure as both: A collaborative education platform and a model of shared urban intervention. We claimed that the economic and programmatic power of our public university can be leveraged for communities to develop their own public spaces and social housing. As a distributed system of public spaces transgressing the wall, the community stations spatialize social justice, mobilizing cross-border citizenship culture through cultural action. With our community partners, we have co-developed four Community Stations, two in San Diego, two in Tijuana. Let’s move from north to south.

The UCSD-EarthLab Community Station is a partnership with Groundwork San Diego, an environmental justice community-based organization, located in the low-income, primarily black and Latinx neighborhood of Encanto, a community characterized by high unemployment, low educational attainment, food insecurity and cyclical poverty. The Station occupies a 4-acre vacant parcel owned by the San Diego Unified School District, who granted the parcel to our partnership, to increase educational capacity for the eight public schools within walking distance of the site. This access to municipal land gave us leverage to assemble a unique cross-sector collaboration between a major research university, a local school district and a grass-roots organization, to co-develop public space, placing education at the center of community development. 3000 kids and their families circulated through the EarthLab each year, and during the current transition it continues to operate as an outdoor, socially-distanced classroom.

With our community partners and local school teachers we are designing an experiential, environmental, pedagogical method to open doors for local youth to see themselves reflected in the environment, understanding that care for nature resembles care for each other and their community. We propose new interfaces between indoor and outdoor, academic and experiential education, to advance creative intersections between science, arts, humanities and socio-emotional learning, all mobilized through restorative practices, linking social and environmental empathy, as catalyst for a new ecological imagination, defined by interdependence, empathy and co-existence.

This experiential method at the UCSD-EarthLab is supported by an integrated ecology of spaces for climate education. The School District has committed capital toward a more refined physical resolution for the site, for what has been so far a largely informal effort. UCSD will invest in sustainable educational programming, research, and management, in collaboration with Groundwork, who will steward community participation. Pedagogic zones at the site are focused on habitat restoration through Energy, Water, Food, and Community programs, all wrapped by Indigenous Kumeyaay knowledges and environmental practices. Ultimately the UCSD-EarthLab Community Station will perform as an open-air “Climate Action Park” designed for environmental education and climate justice. The district has also committed to funding for a new Climate Action Design Building to anchor the site, and as a pilot for post-COVID porosity in classroom design. This new ecosocial infrastructure will break ground in 2023.

Moving south, the UCSD-CASA Community Station, is a partnership with the non-profit Casa Familiar, a 30-year-old community-based, social service organization. It is located in the border neighborhood of San Ysidro, site of the busiest land crossing in the Western hemisphere. The community is 90% Latinx, and has one of the highest unemployment rates, lowest median household income and worst air-quality in San Diego County. The heart of this Community Station is a beloved historic church, that sat for decades in disrepair, and which we were able to rescue through this project, with our partners. With the adaptive re-use of this historic building as catalyst, we designed the UCSD-CASA Community Station as a double project: A parcel-size social infrastructure, made of spaces for cultural and economic activity is flanked by affordable housing. We renovated the historic church into a community theater with an outdoor stage. This performance space is flanked on one side by a series of small accessory buildings for Casa Familiar’s social programming, and on the other side by an open-air civic classroom-pavilion. This social, educational and cultural infrastructure anchors ten units of affordable housing, at both ends of the parcel, all mediated by pedestrian walkways.

We completed construction of this station just before COVID-19 hit, and the residents moved in. It was locked down during the pandemic, but it’s a site built for social proximity, and we have now returned, cocurating in-person cultural programming with our partners. Affordable housing takes on a different meaning when it is deliberately threaded into spaces for social programming, summoning residents to participate in the development of local economic and cultural production and synergizing spaces, programs, resources and people. This is an integrated socio-spatial system that is programmed between university and community.

Let’s imagine a small coalition of local artists, promotoras, and neighborhood youth collaborating with university curators, theater script writers and visual artists, who come together periodically to co-produce a play that explores an urgent issue facing the community, enacted by local youth in the community theater. These artistic productions are rooted in neighborhood stories and become bottom-up, evidentiary material to increase public knowledge and policy transformation. Take for example a project on air quality led a few years ago by UCSD MFA graduate student Andy Sturm. He and our UCSD students were invited to visit the backyard of San Ysidro resident Guillermo Cornejo, to see his lemon trees. Every lemon was coated with black silt, produced by tens of thousands of cars idling daily a few blocks away, waiting to cross the border. The lemons became powerful bottom-up evidence for the community, and with neighborhood youth we explored the intersection of border policy, community health, story-telling and activism. Border Lemons visualized power, mobilized community awareness, and opened dialogue with agencies that govern air quality policy in the border region.

Moving now across the border, our two community stations in Tijuana are located in the Laureles Canyon, an informal settlement adjacent to the border wall. This location is at an important juncture of conflict. Here, the topography of Tijuana’s canyons clashes with the border-wall, before spilling north-bound into the Tijuana River Estuary, an environmentally protected coastal reserve in San Diego, now layered with security infrastructure. At this hot-spot, the conflict between natural and jurisdictional systems, and between ecological and political priorities, is profound. Zooming closer to the ground, we can witness a collision between the estuary in the U.S., the border-wall, and the precarious informal settlements of the Laureles canyon, home to 100,000 people. This site sits just thirty minutes from our campus and demonstrates the dramatic proximity of wealth and extreme poverty in our region. Laureles Canyon is impacted by dump sites, drastic erosion, flooding and landslides, and all of this is exacerbated by the dramatic precipitation fluctuations of climate change. Laureles Canyon lacks water and waste management infrastructure to mitigate these impacts, and much of the trash, along with tons of sediment, flows northward ending in the estuary in San Diego, contaminating this shared bio-regional asset. Here, the border wall is an artifact of environmental insecurity.

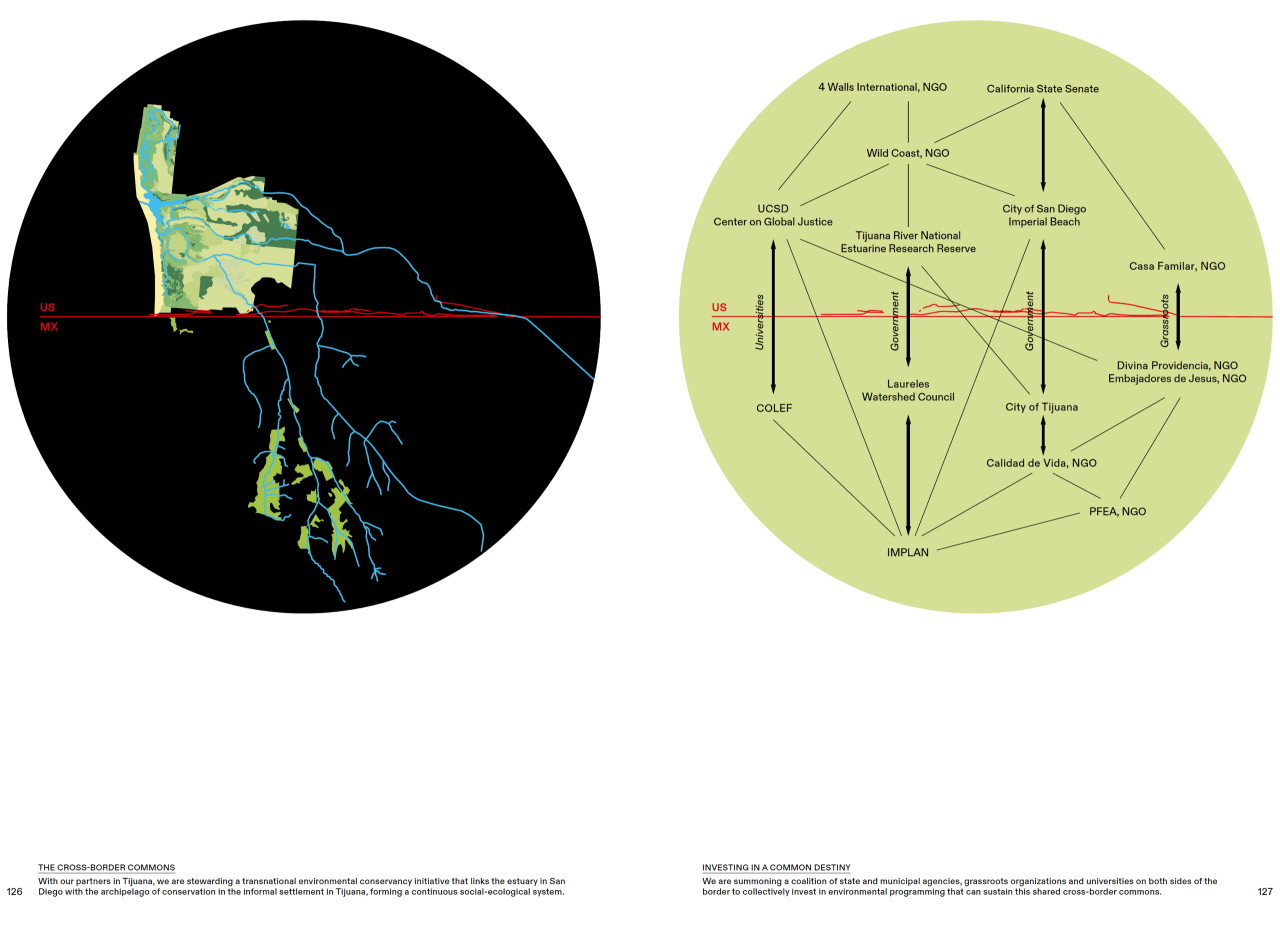

These impacts have intensified in recent years because of a profound lack of collaboration between San Diego and Tijuana to manage these cross-border flows. In the last decades, 70% of the open lands in Laureles Canyon have been lost to irregular urban growth. We have been identifying and bundling unsquatted lands in the settlement that are still environmentally rescuable, to shape an archipelago of conservation. We are advancing an ambitious regional project called the The Cross-Border Commons, an environmental conservation initiative that links the Estuary in the U.S. with the informal settlement in Mexico, forming a continuous social and ecological envelope that transgresses the wall, and protects the environmental systems shared between these two border cities.

With our Tijuana-based activist partners we have curated a coalition of state and municipal agencies, grass-roots organizations and universities on both sides of the wall, and we are now negotiating with the municipality to gain access to the remaining public lands inside the informal settlement. We have been given access by Tijuana’s municipality to the first “island” to co-develop the first ecosocial pilot project. In 2015, the community of Miramar was impacted by a landslide on a hillside in which nineteen homes were destroyed. The landslide fractured this community, disconnecting it from basic services. As the site was abandoned, it became one more dumpsite compromising the entire canyon and the estuary in San Diego. We proposed to transform the landslide zone into a new model of regenerative and transitional hydrological space, as a pilot program for community-led climate adaptability and resilience.

The topographic scar left by the landslide on the slope is being transformed into a green hydrological promenade, a natural biofiltration channel, to transfer stormwater discharges from the upper part of the basin to the creek below, designed to mitigate the risk of landslides and erosion and the integral management of rainwater. It doubles as an eco-pedagogical walk designed to incorporate the participation of local residents, ensuring the maintenance and sustainability of the water system in the long term. The project yields a double concept of public space: as a green sponge but also as a node of awareness of the importance of water. The Miramar project summarizes an important idea for us: Water as a common good, as a tool to summon community appropriation of public space, promoting joint responsibility among neighbors, organizations, universities and the government to promote a new sense of collective ownership of social-environmental assets and spaces. The project began by convening Community Brigades to clear the solid waste at the site, to illustrate how dumpsites can become ecosocial public spaces across the entire Laureles sub-basin.

An important contextual note before we introduce one of the Tijuana stations is that Laureles Canyon has also been the site where we have advanced our research on informal urbanization. As we have written about over many years, the informal settlements of Tijuana are built with urban waste from San Diego, recycling architectural parts to construct habitation and infrastructure. We have learned a great deal from these incremental recycling and building practices, as people construct their own shelter in layers over time. We have also noted that multinational maquiladoras surrounding these informal settlements typically benefit from easy access to cheap labor. Over the years we have experimented with factory-made material systems to structurally mediate the recycling of waste. We have proposed an ethical loop where factories invest in emergency housing. For many years we have partnered with Mecalux, a Spanish maquiladora that produces lightweight metal shelving systems for global export. Together we adapt its prefabricated systems into structural scaffolds for informal housing. We designed a catalog with the factory’s engineers to test a variety of prototypes and configurations, illustrating how top-down institutional resources can support the bottom-up creative intelligence of informal urbanization. The capacity to redirect the material systems and surplus value of a maquiladora to sites of emergency was an important milestone in our research-based practice.

Our two community stations in Tijuana operate within this rich ecology of social, environmental, economic and material relations and partnerships. The UCSD-Alacrán Community Station is located in the most rugged, precarious and polluted sub-basin of the canyon. It is a partnership with Embajadores de Jesús, a religious organization led by activist-pastors Gustavo Banda-Aceves and Zaida Guillen. With limited resources, Embajadores began construction of a refugee camp, to provide shelter, food, and basic services to hundreds of Haitian and Central American refugees while they navigate unjust asylum processes in the U.S. and Mexico. With the help of skilled migrants, they began building their own emergency housing. We have now established a long-term partnership to co-develop a Community Station here, to increase refugee housing capacity. We are accelerating production of Mecalux frames to install them on vernacular post and beam concrete systems into a housing-infrastructure.

The housing “scaffolds” were built first, leaving the interiors as “planned open systems,” equipped with utilities to support incremental live-work configurations. These envelops are the seeds for an evolving sanctuary neighborhood, to be infilled through time by the migrant residents themselves. We see migrant housing as a mechanism for generating jobs. To sustain the construction process over time, we are designing a sanctuary economy. We embed refugee housing in spaces of fabrication, training, small-scale economic development. With the support of the PARC Foundation we have assembled a community-owned business, with a tool library, wood and metal machines, and a couple of trucks and tractors. The community is presently completing construction of this site, and the cooperative will remain operational for future construction jobs across the Laureles Canyon.

The UCSD-Alacrán Community Station began construction last Summer. The migrant community assembled the adapted shelving systems into housing frames. But we also began healing the topography, creating hydro-filtration channels, gabions, terracing and water collection systems, advancing migrant housing as an ecological restorative infrastructure. This seed project for an evolving sanctuary ecological neighborhood will be exemplary of how to develop the future of this informal settlement, integrating social and environmental justice issues and a laboratory for rethinking the city at large in terms of a more integrated and inclusive idea of urban-ecology. Here we work with community leaders, students and researchers, on social protection from landslides, floods and estuary health beyond the wall. We lead educational programming through which young people understand zones of vulnerability in their own neighborhoods, emphasizing ecological conservation of species and habitat restoration—it’s never too early to begin. We have committed to elevating children here as the cross-border citizens of the future.

Unwalling Citizenship

There is so much more to say about our four UCSD Community Stations, about our amazing partners, and what we do together in these spaces. While the stations focus on different issues reflecting the priorities of each community, they are all richly curated for dialogue, collaborative research, urban pedagogy, participatory design-build, and cultural production. They all aspire to increase public knowledge; challenge divisive political narratives; foster solidarity and collective agency; and advance strategies to counter exploitation, dispossession, deportation and environmental calamity. These activities often invite encounters with formal institutions of power that govern the border zone. Sometimes these meetings facilitate mutual recognition and cooperation, and sometimes they do not. For us, the goal is less about resolving conflict, than about understanding, recognizing and democratizing it. We see democracy in the border zone as a bottom-up process of exposing and rendering more accessible the complex histories and mechanisms of injustice that are too often hidden within official accounts of who “we” are.

Racist political narratives in the U.S. portray the border as a site of rupture and criminality, but we are committed to generating different stories, counter-narratives about life in this region, grounded in the experiences of those who inhabit it. We are a region of flows and circulations, shared practices and aspirations, alliances of hearts and minds, regardless of the wall that restricts the movement of our bodies. In this sense the Community Stations become a cross-border observatory, a platform for constructing an elastic civic identity from the bottom-up, a cross-border res publica. With our partners we curate “unwalling experiments” that dissolve the wall—using visual tools like diagrams and radical cartographies to situate border neighborhoods within broader spatial ecologies of circulation and interdependence—from local to regional, to continental and ultimately to global scales. We see elasticity as a civic skill, the ability to stretch and return, between local and more expansive ways of thinking, over and again, to understand one’s challenges within broader dynamics and processes, and to envision opportunities for solidarity and collective action across walls.

Here at the border, the idea of the bioregion—the binational watershed system—has been a powerful imaginary for activating more elastic civic thinking. Several years ago, we curated a cross-border public action through one of the sewerage drains Homeland Security carved into the wall, between Laureles Canyon and the Tijuana River Estuary. We negotiated a permit with U.S. Homeland Security to transform the drain into an official port of entry southbound for twenty-four hours. They agreed, disarmed by our self-description as “just artists,” as long as Mexican immigration officials were waiting on the other side to stamp our passports. Our convoy was comprised of 300 local activists, residents, representatives from the municipalities of San Diego and Tijuana, and artists and border activists from around the world. We summoned agencies who are typically at odds with one another. As we moved together southbound under the wall, we witnessed slum wastewater flowing northbound toward the estuary beneath our feet. This strange crossing from estuary to slum through a militarized culvert, and the stamping of passports inside this liminal space, amplified the most profound interdependencies of our border region. The great insight was that protecting the vulnerable U.S. Estuary demands shared investment in the informal Mexican settlement.

So in this cultural experiment we went down. But sometimes, nurturing civic elasticity requires ascending above the familiar. Imagine a Mexican child standing on a narrow sliver of land along the eastern rim of Laureles Canyon, hundreds of feet above the borderwall. Imagine she plants her feet facing due west, with the vast blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean in front of her, Mexico to her left, the U.S. to her right. Below to her immediate left she sees the dense informal settlement where she lives; she can spot her house, her school, and experience their proximity to a country she and her family are not permitted to enter. Below to her immediate right, almost directly beneath her feet, she sees the borderwall which, from this vantage, looks like a flimsy and ridiculous strip inserted onto a vast and powerful natural system. Lifting her eyes, she sees the green expanse of the Tijuana River Estuary with its vulnerable wetland habitats and sediment basins contrived to catch the northbound flows of waste from her community. And further beyond still, downtown San Diego rising vertically into the sky. From this vantage all the characters of this contested zone come to life. We’ve witnessed this moment of recognition again and again over the years, among children, our students, policy-makers and even foundation presidents. There are few places on earth where the collision of informality, militarization, environmental vulnerability, and the proximity of wealth and poverty, can be so vividly experienced. But in reality, the conflicts we experience here locally between nation and nature are reproduced again and again along the entire trajectory of the continental border between the U.S. and Mexico. Over the years we have collected aerial photos that document precise moments when the jurisdictional line collides with natural systems—powerfully illustrating what dumb sovereignty looks like when its “hits the ground” in a complex bioregion.

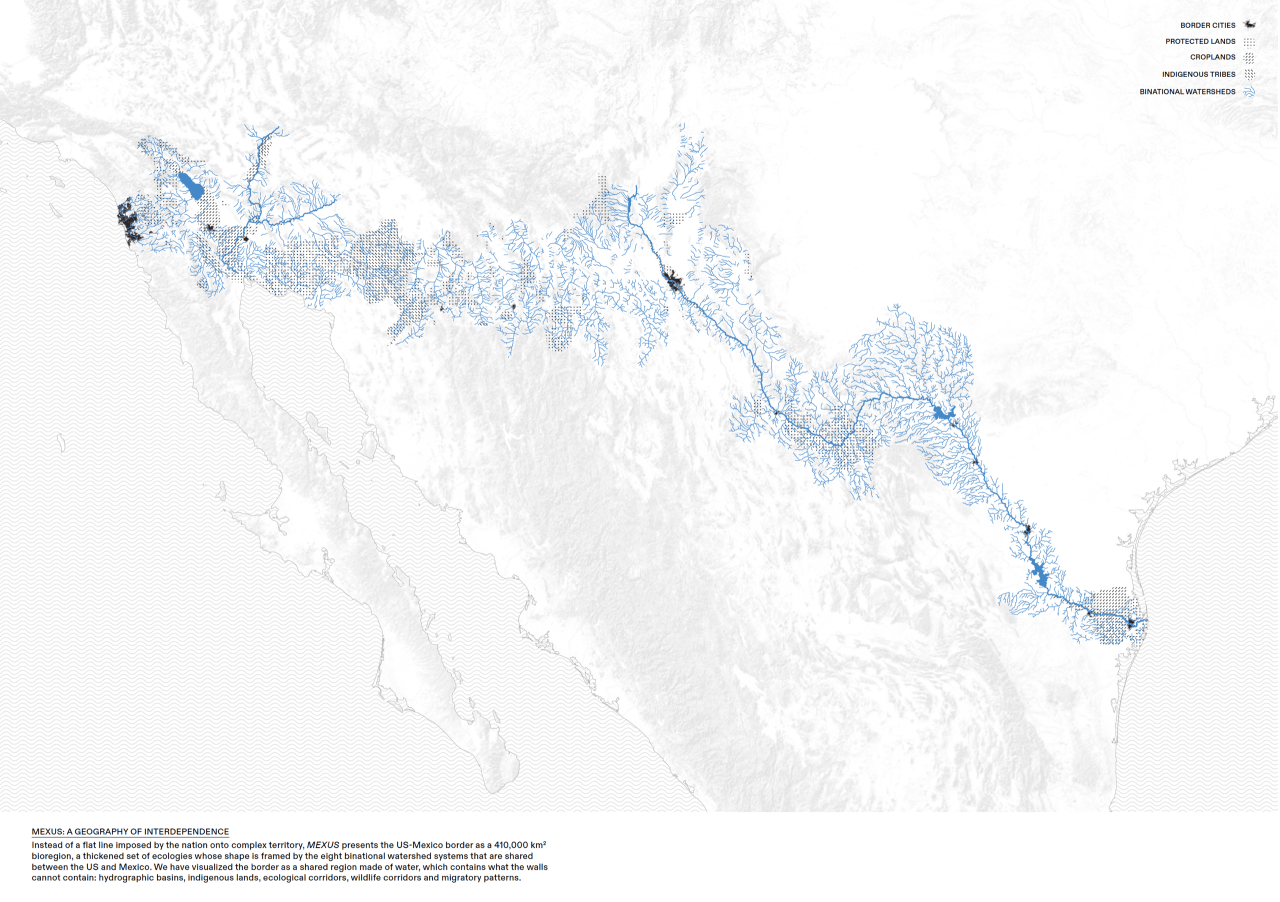

Our MEXUS project stretches our elastic civic aspirations to the continental scale. MEXUS visualizes the entire border zone without the line. It dissolves the border into a bioregion whose shape is defined by the eight binational watershed systems bisected by the international border. MEXUS also exposes other systems and flows across this bioregional territory: tribal nations; protected lands; croplands; urban crossings, many more informal ones, 15 million people, and more. Ultimately MEXUS counters America’s wall-building fantasies with more expansive imaginaries of belonging and cooperation beyond the nation-state. In Community Stations programming MEXUS become a provocation for dialogues about a shared bioregional civic identity among Mexicans, Americans and diverse tribal nations who inhabit this contested space. Now the final civic stretch, literally, is a visualization project called The Political Equator which traces an imaginary line from San Diego-Tijuana across the planet forming a corridor of global conflict between the 30th and 38th parallels north. Along its trajectory lie some of the world’s most contested and violent thresholds.

These include the U.S.–Mexico border at San Diego/Tijuana, the most trafficked international border checkpoint in the western hemisphere; the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, the main route from North Africa into “Fortress Europe”; the Israeli-Palestinian border that divides the Middle East, emblematized by Israel’s fifty-year military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza; India/Kashmir, a site of intense and enduring territorial conflict between Pakistan and India since the British partition of India; the border between North and South Korea, representing decades of intractable Cold War conflict; and China’s accelerating militarization of the South China Sea, along with Taiwan and Hong Kong. Visualizing the Political Equator alongside the climatic equator was an astonishing discovery for us, because the ribbon between them, give or take a few degrees, contains our planet’s most populous slums, its sites of greatest natural resource extraction and export; and its zones of greatest political instability, climate vulnerability and human displacement. The collision of nationalism, climate catastrophe and forced migration is the global injustice trifecta of our time, but as we said at the beginning, these dynamics always hit the ground somewhere, and are experienced by people locally, in everyday places like ours.

Teddy Cruz (MDes Harvard University) is a Professor of Public Culture and Urbanism in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego, and Director of Urban Research in the UCSD Center on Global Justice. He is known internationally for his urban research of the Tijuana/San Diego border, advancing border neighborhoods as sites of cultural production from which to rethink urban policy, affordable housing, and public space. Recipient of the Rome Prize in Architecture in 1991, his honors the Ford Foundation Visionaries Award in 2011, the 2013 Architecture Award from the US Academy of Arts and Letters, and the 2018 Vilcek Prize in Architecture.

Fonna Forman (PhD University of Chicago) is a Professor of Political Theory at the University of California, San Diego and Founding Director of the UCSD Center on Global Justice. Her work engages the intersection of ethics, public culture, urban policy and the city, with a focus on climate justice, border ethics and participatory urbanization. She serves as Co-Chair of the University of California’s Global Climate Leadership Council; and served until 2019 on the Global Citizenship Commission, advising United Nations policy on human rights in the 21st century.

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman are principals in Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman, a research-based political and architectural practice in San Diego investigating borders, informal urbanization, civic infrastructure and public culture. They lead variety of urban research agendas and civic / public interventions in the San Diego-Tijuana border region and beyond. From 2012-13 they served as special advisors on civic and urban initiatives for the City of San Diego and led the development of its Civic Innovation Lab. Together they lead the UCSD Community Stations, a network of public spaces across the border region co-developed between university and community for collaborative research and teaching on poverty and social equity. Their work has been funded by the Ford Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, ArtPlace America, the PARC Foundation, and the Surdna Foundation, among others.

Their work has been exhibited widely in prestigious cultural venues across the world, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum, New York; Das Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin; M+ Hong Kong, the 2016 Shenzhen Biennial of Urbanism and Architecture, and representing the United States in the 2018 Venice Architectural Biennale. Their work is part of the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. They have two new monographs: Spatializing Justice and Socializing Architecture: Top-Down / Bottom-Up (MIT Press and Hatje Cantz) and one forthcoming: Unwalling Citizenship (Verso).

Notes

1. This lecture was delivered in The Web of Life symposium on March 18, 2022. Our great thanks to the late Newton Harrison and Tatiana Sizonenko for inviting our participation, and to Leslie Ryan for facilitating wonderful conversations during this period. Thanks to Grant Kester for organizing this collection of essays in FIELD, to honor Newton’s memory.

2. For more detailed discussion see Spatializing Architecture: Top-Down / Bottom-Up (Cambridge: MIT Press and Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag), 2023.