Meditations on the Harrisons

Alejandro Meitin

Now that Newton has followed in Helen’s footsteps, I write this text as if immersed in a dream, flying over mixed memories of passing images, and with the internal resonance of those voices that showed us a way, to rescue moments of those who have been both souls for me, and teachers. I go back to the times when Ala Plástica, the ecological art group born in 1990 in the Río de la Plata, Argentina and active until 2016, felt we needed to get out of public art focused on urban settings and instead begin to address large ecosystems and watersheds as a framework for our artistic practice. [1] I am talking about the time of the dream of the global democratization of information, of the birth of telematic communication networks, when the Internet was just beginning to appear, when there were only one million computers connected to the World Wide Web, and when through operating systems now obsolete, we were beginning to explore in real time the things that were happening in other parts of the world. We were able then to jump great distances and influence with our opinions and our first projects, new areas of critical art. This period also marks the beginning of a new environmental discussion, in which new expressions were generated, accompanied by inspiring new areas of interdisciplinary research, such as so-called “complexity theory,” or simply complex systems, including physical, computational, biological and social. Other new forms of spatial analysis began to evolve as well, including GIS tools which allowed us amazing approximations and models through which to understand and plan diverse spaces. Among all this magma, appeared the pioneering work of the Harrisons and their way of operating within the scientific and professional environment, as well as preserving the intuitive ways of thinking and working typical of the art world. [2]

Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison worked for nearly fifty years with biologists, ecologists, architects, urban planners, and other artists to conduct collaborative dialogues in order to discover ideas and solutions that support both biodiversity and community development. They discovered that the world was a space full of threats, but at the same time a universe of opportunities to revise the most common assumptions about the role of artistic production in modernity. They advocated another answer to the questions, “What is an artist? How is art linked to the social and environmental space? What are the limits and common spaces between art and other practices? Their role as investigative artists allowed them to come into direct contact with environmental problems where the ecological balance was in danger of being destroyed, stimulating discussion, debate and media attention. This allowed them to display their photographic narratives, maps, drawings, texts and performances both in spaces of traditional artistic representation, as well as other sites unfamiliar with this type of expression. This was the advantage of the line of flight that the Harrisons developed and showed as a path. Challenging narrow lanes, they opened the discussion and gave rise to the ecological shift and the struggle of worldviews that this shift entails. The proposed artistic action as a device of vision—indeed, of worldview—installed in this new territory. In this way they knew how to generate novel narratives to understand the world and the things that surround us.

As inhabitants of the Río de la Plata estuary, an immense basin where the fluvial collides with the marine, shaping and transforming our coasts and the people who live in it, it was the Harrison’s work The Lagoon Cycle (1974-1978) dedicated to the lagoons of several important estuaries in the world, that attracted us as soon as we became aware of it.[3] This work, represented in the form of a 360-foot-long, eight-foot-tall mural, was one of the first long-term environmental and artistic initiatives. It is predicated on a dialogue between two characters, the ‘Lagoon Maker’, represented by Newton, who promotes the ongoing progress of business interests, and a ‘witness’ by Helen, who exerts a fantastic counterpoint to proposals based on practical purposes offered by the ‘Lagoon Maker’ on seven lagoons. Based on the interpretation of that work, in fusion with many other ideas that occupied us at that time, the Junco/Emergent Species project was born in 1995, which involved the planting of reeds (Schoenoplectus californicus) along the coastal areas of the Río de Silver, in order to create new ecosystems.[4] The study of the extraordinary propagation system of the rush, its ability to create new territories and its aptitude for purifying pollution, allowed us to activate the metaphor of rhizomatic expansion and the emergence of a series of interconnected exercises in the Río de la Plata estuary. From there, the Bioregional Initiative was born, a long-term strategy for the development of a series of interconnected exercises based on the principle of social assemblage. We sought to explore the potential of developing activities integrated into the cultural and biophysical ecology of the Cuenca del Plata area as a vehicle for social and environmental regeneration that continues to this day, promoted by Casa Río: Laboratorio del Poder Hacer (River House: Building Power Lab).[5]

In other works such as Sacramento Meditations (1977) the Harrison’s criticized the tax subsidies that perpetuate the inefficient practices of intensive irrigation in the agricultural lands of California’s Central Valley and warned through different means (radio, prominently displayed posters and billboards and performances in various museums in the city of San Francisco) of the damage to the ecosystem resulting from pesticides, fertilizers, dams and river diversions, employed to carry out intensive irrigation practices on agricultural lands.[6] Newton’s poetic prediction and dramatic warning that California’s Central Valley would become a pile of dust and his promotion of the idea that human activities must correspond to the physical laws of the universe hold true when we look at the consequences of man-made management of the basin and the results of the extreme droughts that today affect 85% of the state, leading to the loss of habitat for most animal species due to agriculture and urban development. Most of the Harrisons’ previous and subsequent works dealt with vital elements such as wetlands, water systems and the beings that inhabit them, proposing an aesthetic and imaginary drift from a post-human, materialist perspective.

We met Helen and Newton personally in 1998 in Dublin. More precisely at the Dun Laoghaire Art Institute, where we participated in the 2nd Littoral meeting called “Critical Sites.” Littoral was a very valuable initiative to create an independent international network of artists, critics and teachers interested in contributing to new thinking on contemporary art practice, art research and pedagogy, organized by Ian Hunter and Celia Lerner of Projects Environment. Immediately after the conference we met again in Northern Ireland, more precisely in County Armagh, the mother house of Irish Christianity. At that time, together with my colleague Rafael Santos, who unfortunately passed away in 2021, we were carrying out an emerging proposal from the Littoral meeting called Ards Peninsula Fishing Port (Critical Sites 1998) an artistic, community and environmental research exercise related to regional development by South Belfast. We were there exploring the possibility of identifying diversification models to help restructure the seaports and fishing communities of the Ards peninsula. From this meeting we feel honored by the Harrison’s interest in our work and by a friendship that was born there and has been maintained throughout all these years.

The Harrisons came to Northern Ireland to make a series of presentations and contribute their views at meetings taking place in the tense border area. At that time, the aim was to put an end to The Troubles through the “Good Friday Agreement” and, in a certain way, artistic projects that were linked to communities were welcome within the framework of the Blackwater Catchment Rural Development Strategy (1997), a project financed by the European Union, comprising Dungannon District Council, Armagh City and District Council and Monaghan County Council.[7] The Harrisons made a presentation that focused on the project they were developing at the time, called Casting a Green Net: Can it Be We are Seeing a Dragon?[8] This was a far-reaching work, intended to connect fragmented sites, and to create a green network to support the development of economically, socially, culturally, and of course ecologically, diverse communities, in the North of England. During that time we participated in meetings with local contacts in the Blackwater River area, which acts as the natural boundary between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, flowing between the beautiful counties of Armagh, Tyrone and Monaghan. I recently asked Newton if he remembered those days, and his response was as follows: “I still remember well the people who questioned the right of others to be in the meeting.” Without a doubt, and as I also remember them, the internal tensions between unionists and Irish republicans were evident.

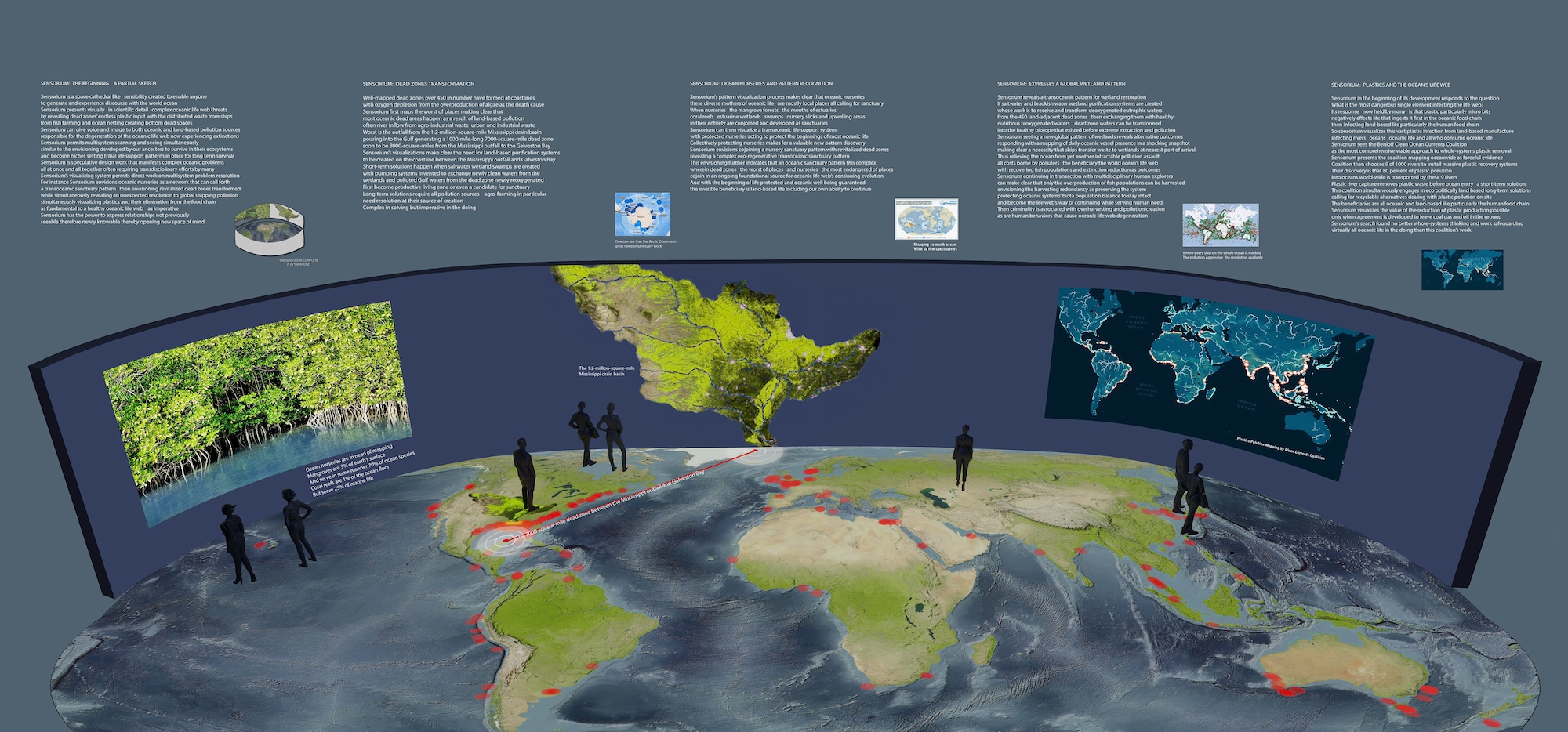

Since that time we have shared talks and spaces in exhibitions, perhaps the most significant of which was Groundworks Environmental Collaborations in Contemporary Art, a project organized by the Regina Gouger Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon and curated by Grant Kester, which took place between October and December 2005 at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[9] Together with the Harrisons, artists from the U.S., Argentina, Austria, England, Germany, India, Japan and Senegal participated in that exhibition. In the words of the curator “the exhibition projects embody a relationship with nature not as something to be mastered, transformed or used, but as an interlocutor and agent that speaks to us in a language that we are not always prepared to understand”. Sometime after Helen’s departure, Newton invited me to remotely share some thoughts about Sensorium, his most recent effort to address the destruction of the world’s ocean web of life.[10] This project, inspired by him, was born from the Center for the Study of Force Majeure located at the University of California Santa Cruz.[11]

The Sensorium project, existing currently as a kind of sketch for a larger project, is as much a work of art as it is a scientific proposal that aims to condense the survival problems facing the world ocean. This work incorporates elements of 2D, 3D, VR, and sophisticated audio tools, with the goal of creating an immersive experience that brings together visual, audio, and haptic experiences in real time to become the voice of the world ocean. In technical terms, a sensorium is the sum of an organism’s perception. In Newton’s opinion, it is “something that our ancestors practiced as part of their daily survival mechanisms and that has now faded to a whisper in modern Western life.” The sensorium includes sensation, perception, and interpretation of information about the world around us by using the faculties of the mind such as the senses, phenomenal and psychological perception, cognition, and intelligence. This form of interpretation is totally different from decision-making of a Cartesian nature, which fragments the world as a mechanism.

The Sensorium project begins with empathy and outrage. Empathy for a wounded system and indignation at the pain, injustice and indifference generated by the comprehensive destruction of the Web of Life. An ocean damaged by exploitation that speaks to us with a voice from the Sensorium. The speaking ocean tells us that there are 450 dead ends on a global scale. Most of the oceanic dead areas occur as a result of terrestrial contamination, one of them is indicated in the area of the Río de la Plata estuary in Argentina, perhaps one of the most contaminated areas in the world as a result of extractive processes, particularly those linked to agribusiness. The voice of the world ocean tells us that one way to regenerate these dead points is to recover the “nurseries” of purification from which life springs. These “nurseries” begin in wetlands, but more than 50% of these vital ecosystems have been destroyed, therefore the first thing to do is to restore them. For this I believe in the need to find restorative gardeners of wetlands, to ask them how a global restoration program for wetland ecosystems can prosper.

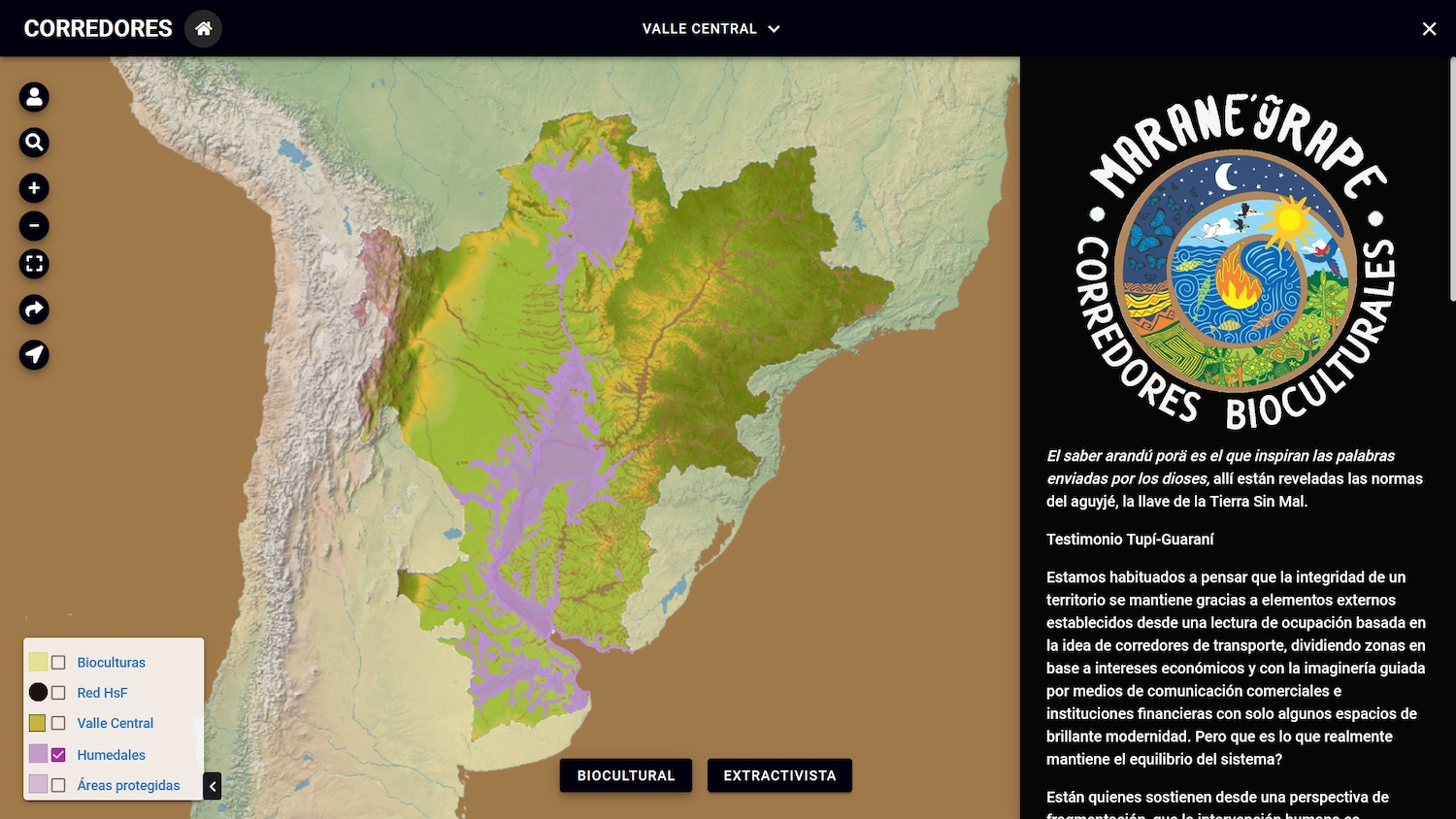

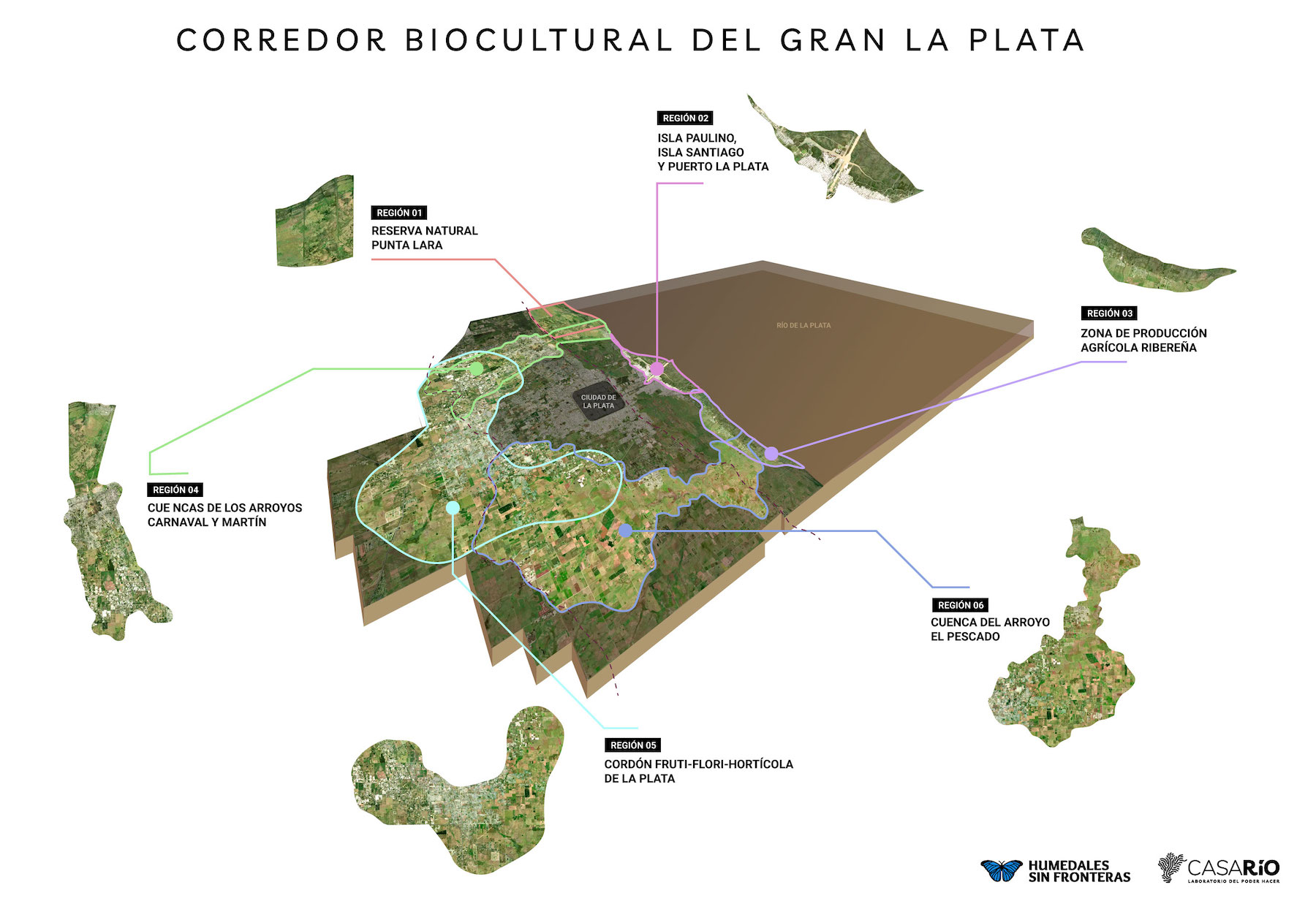

In the Southern Cone of Latin America, these gardeners are a group of civil society organizations from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and the Netherlands. They have a long common history of multifaceted activism involving art, scientific knowledge and local knowledge and are carrying out a transnational basin governance program, called Wetlands Without Borders, which is aimed at preserving and recovering the most extensive freshwater wetland corridor on the planet, which runs through the so-called Central Valley of the Cuenca del Plata.[12] The Paraná, Paraguay and La Plata rivers flow freely for almost 2,300 miles, from their source in the Great Pantanal to the Rio de la Plata estuary, irrigating gigantic ecosystems of enormous biological and cultural value, to finally flow into the Atlantic ocean.

These gardeners tell us that to maintain the regenerative capacity of a system it is vital that the terrestrial biological corridors remain interconnected, in order to allow the continuity of ecological processes, such as genetic exchange, evolution, migration and repopulation. But, in the manner of the sum of perception proposed by Sensorium, it is also necessary to involve knowledge, beliefs, and practices in which a symbolic-biotic fabric is put into play, where worldview, myth and ritual, history, memory and cultural expressions, act as dimensions of the larger territory. What we could call the “biocultural dimension”. [13]

It is possible to visualize the different instances of integration and fragmentation in the mapping of the biocultural corridor of the Central Valley of the La Plata Basin.[14] This is part of a project that we developed together with the art critic, cultural theorist, cartographer and activist Brian Holmes, along with activist and grassroots organizations, institutions and a team of artists, communicators and programmers. The expression of any given bioculture contains a series of values and elements of symbolic, historical, epistemic and political significance. The concept of bioculture implies, as well, the recognition of communities as fundamental political subjects. For this reason bioculture can be understood in terms of biocultural epistemology, biocultural diversity, biocultural ecology, a biocultural reserve, a region’s biocultural, and biocultural corridors. Biocultural corridors can only be fully understood in the context of the biological, symbolic, cultural, and historical fabric, in which life develops.

There are those who maintain, from a fragmentation perspective, that human intervention is incompatible with a balanced ecosystem. But in fact, there are forms of biocultural integration that don’t necessitate the fragmentation of life. This is an ecosophy of relationship with the environment that projects practices that are associated with the term “mutual upbringing” or “mutual promotion” (uywaña in the Aymara language of the Andean highlands) which implies “cultivation, protection, encouragement, protection.” This practice is linked not only to the cultivation of plants and the care of animals, but also to the care that humans lavish on each other and that humans extend to non-humans. In the academic literature, the word “domestication” generally refers to “dominance” or “control”, linked to the idea of “domesticated” as “uniform”, “predictable” and “unique”. Parenting, on the other hand, implies conversation, dialogue, understanding, negotiations, reciprocity, exchanges and agreements between human and non-human entities.

It can be seen how this concept charges plants, soils, climate, animals, hills and space with agency, unlike the idea of resource “management” which gives them a more passive character (and consequently makes them easier to control). All these agents transform each other and, in doing so, they transform the world which they inhabit; history is the process by which humans and non-humans are continually pushing each other to “be.” This scale is vital and in this sense this vision is connected with the thought that Newton expresses in “Note to Many Communities in Need of Becoming One Community”:

The question at hand is, what would an ecologically nurturant human community actually look like and behave like? We probably need to collectivize in a yet to be discovered manner. Personally, I am intuiting a return to an exchange-based, gift-based, mutually-nurturant human culture that re-establishes its place in the Life Web so needed for our survival.

As I return from this immersive sensorium reverie of writing, it only remains for me to say that these contagions of intuitive, emotional, imaginative and sensory forms that characterize the Harrison’s art have extended a nurturing influences across many dimensions of human understanding, and will continue to exercise a transformative influence on those of us who are committed to a profound and transcendent change in the kingdom of this world.

Alejandro Meitin is an artist, lawyer, social innovator and founder of the artistic collective Ala Plástica (1991-2016) based in the city of La Plata, Argentina. In 2018 he founded Casa Río Lab, from where he collaborates with young people, farmers, artists, activists, architects, landscape architects, local authorities and pollution control experts to create proposals on rivers and coastal ecosystems.

Notes

[1] https://alaplastica.wixsite.com/alaplastica

[2] https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/

[3] https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/the-lagoon-cycle-1974-1984-2

[4] https://issuu.com/alaplastica/docs/1995_-_iniciativa_bioregional_l_jun

[5] Over the last decade, Casa Río: Laboratorio del Poder Hacer (River House: Building Power Lab), has developed a spectrum of projects involving advocacy for social and ecological justice, communication and community building, policy development, mapping and other visual products. The primary aim of Casa Rio is to develop biocultural forms of civic engagement tied to understanding the coevolution and co-dependence of human, plant and animal ecologies in the Rio Paraná, one of the world’s largest wetlands. (https://www.casariolab.art/)

[6] https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/sacramento-meditations-1977

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Troubles

[8] https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/casting-a-green-net-can-it-be-we

[9] https://groundworks.collinsandgoto.com/

[10] Newton Harrison, “Sensorium–The Thinking,” Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, vol. 2, no. 1 (2021). [open access internet journal]. http://en.ecopoiesis.ru (d/m/y)

[11] http://www.centerforforcemajeure.org/

[12] https://humedalessinfronteras.org/en/

[13] Bioculturalism (bioculturalidad) is a paradigm for understanding the coevolution and interdependence of biological and cultural diversity. The concept owes its origins to ethnobiology, has been taken up by diverse social and natural scientists, and has been extensively developed and disseminated in the work of the Mexican ecologist and biological anthropologist Victor Toledo. Bioculturalism is an organizing framework for integrative and innovative ways of thinking about heritage, sustainability, urban regeneration, and food production. Bioculturalidad has also become a guiding framework for a number of organizations working at different scales from the local to the transnational, including the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, Terralingua, Plataforma Biocultural, La Trajinera del Conocimiento, and Casa Rio Lab.