Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison: Meditations on Climate Change

Tatiana Sizonenko

Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022), simply known as the Harrisons, were California-based multidisciplinary artists who became widely recognized for their ecological work. Many artists continue to be inspired by them, as the ecological artist and activist Lillian Ball affirms: “They were the forces of nature whose ongoing influence will be felt throughout generations.” Their collaboration, which lasted nearly fifty years, ultimately led to the first husband-and-wife shared professorship at UC San Diego. After Helen passed away in 2018, Newton continued their urgent ecological legacy at the Center of the Force Majeure they co-founded at UC Santa Cruz in 2007, working until the last days of his life on his final new work, A Sensorium for the World Ocean. Underpinned by the astute commitment to “listening to the Web of Life,” in Newton’s words, the Harrisons’ pioneering art-and-science collaboration not only ignited the field of ecological and environmental art, but also helped to establish ecological art as a distinctive sub-category that focuses on the biological interdependencies in ecosystems.[1] Working in the domains of art and science, the artists engaged a wide range of media, including drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, mapping, poetry, architectural design, technological experiments, land reclamation, watershed and ecosystem restoration, and re-terraforming practices.

The Harrisons’ art combines these many disciplines to address the climate crisis head on and to reveal the environmental degradation of many ecosystems, due to chronic mismanagement of natural resources. These failures were further accelerated by profit-driven industrial processes. Reassessing the artists’ commitment to interdisciplinary research, Edward Shanken emphasizes that “the Harrisons have had to master environmental science” in order to understand ecosystems, “to work with them as an artistic medium, and to create successful ecological and environmental interventions.”[2] In view of the climate crisis unfolding around us, the Harrisons’ work appears more urgent, prophetic, and relevant to current environmental concerns in both the local and global contexts than had been previously realized. Their work began to engage the prospect of climate change long before it was widely discussed. As early as 1974 they were examining rising sea levels and possible massive environmental changes that could dismantle many of the ecosystems on the planet. The Harrisons would propose a distinctive form of eco-futurism, calling on artists to contribute unique perspectives and methods that differ from those of environmental and social scientists and engineers, to sustain the planet by reframing culture and technology, or by creating a new culture entirely. In addressing “the pressure of global warming on all planetary systems,” the Harrisons have presented far-reaching scenarios of human-induced changes in ecosystems and asked new questions that, in Newton’s words, “scientists would not be able to say, but they as artists could.” [3]

Beginnings

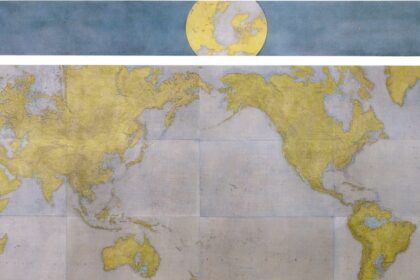

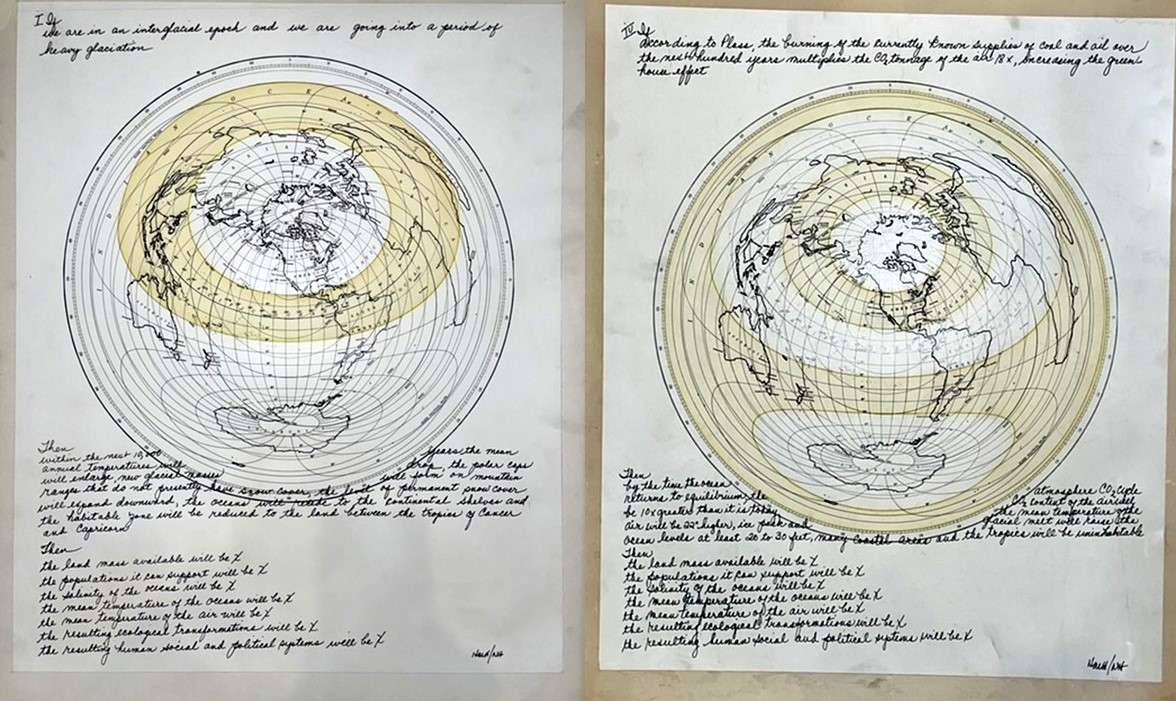

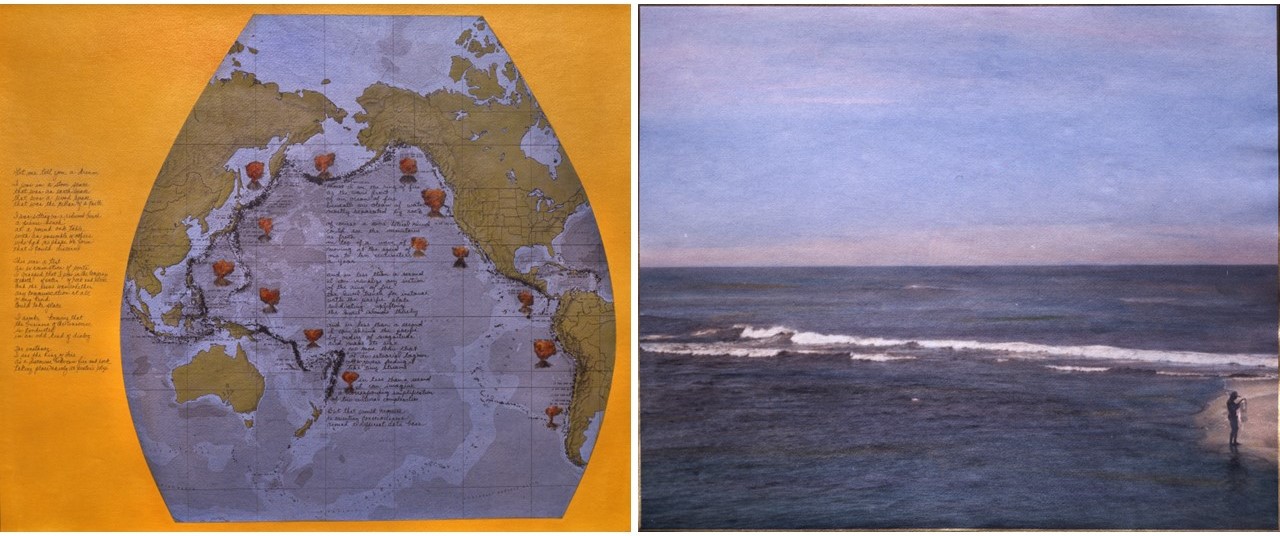

The Harrison’s first conceptualized the idea of climate change and its implications for our planet in San Diego as the Center of a World in 1974.[4] Helen found a book by Gilbert Pass, who made the powerful argument that the burning of coal and oil would cause global warming, and thus higher CO2 levels, an accelerated greenhouse effect, melting glaciers, and a rise in temperature and sea levels. Helen also picked up a book by Robert Bryce who argued that the planet was in an interglacial period and would in fact get colder. Employing the strategies of conceptual art, word-image play, and irony, the Harrisons visualized the implications of the arguments of both Bryce and Pass by proposing short- and long-term scenarios of melting and/or freezing. The resulting work comprises five photo-text images featuring an elegant equidistant Mercator projection map of the Earth, with San Diego, the locus of the artists, at its exact geometric center. Each work suggests a different scenario and proportion. The first three maps address Bryce’s argument, picking a different moment from a period of glaciation. Map IV projects a global warming scenario based on Pass’s argument, by positing a mean air temperature rise of 22 degrees and an ocean level rise of at least 20-30 feet, with many coastal areas becoming uninhabitable, leading to profound ecological, social, and political transformations. Map V advises if one of the proportions I through IV are true then “begin long-range planning.” However, if it cannot be determined which proportion is true or which combination of proportions is true, then an accompanying text below the map advises, in Helen’s words (essentially), “Begin both long- and short-range planning.”

San Diego as the Center of a World was the Harrisons first artwork to whimsically engage the problem of climate change. Embedded in the narrative, the image of a wittingly “decentered world” told the story of different possible climactic scenarios and the shocking implications in a language that people could understand. Their visualization of the 200-page arguments of Bryce and Pass in compelling image-word maps was an invitation to a dialogue so that, as Newton said, “everyone could see what could potentially happen and they become their own planner.” It was an indication of their transformative thinking and steadfast commitment to the idea that the planet was their client and that they would only do work to benefit the ecosystem. This was the last work in which the Harrisons’ roles were discrete. Their collaboration essentially changed and became co-equal, as they began imagining that there was “a third party, a unique co-creator—the real artist,” visible only to them. [5]

San Diego as the Center of a World anticipates a pivotal reading of climate change in their major work the Lagoon Cycle. Conceived as a dialogue between the Lagoonmaker and the Witness, the Lagoon Cycle (1974-84) visualizes a story involving an unlikely hero, a Sri Lankan crab named Scylla serrata (Forsskal), who is transported to the West Coast of the United States. The story unfolds, in Newton’s words, as a “monumental mural, a picturesque novel, and a storyboard for a movie.” At the heart of the Lagoon Cycle are several wide-ranging themes: the consideration of lagoons and watersheds as complex self-sustaining polyculture ecosystems, the relationship of ecology and culture, the future of ecological and eco-cultural wellbeing, the delusions of experimental science, and the inadvertent harmful outcomes of mega-technology on nature.

As a metaphor for nature and culture, the Harrisons chose the estuarial lagoon, a special place with a rich variety of life, yet also fragile. In the Third Lagoon, the Lagoonmaker says:

An estuarial is a place where fresh and

salt waters meet and mix it is a fragile meeting

and mixing not having the consistency of the ocean

or the rivers it is a collaborative adventure

its existence is always at risk…

but life in the lagoon is very special it has evolved

high tolerance to the stresses that come about from

Sudden changes in fresh and salt waters and

temperature and available food for the life web.

Life in the lagoon is tough and very rich…

Developed as an artistic visualization of the Harrisons’ experimental scientific work on how living organisms react to a specific environment, the Lagoon Cycle presented a firm argument against industrial exploitation of the environment leading to the depletion of ecosystems. The Lagoon Cycle, comprising seven parts or “lagoons,” begins by studying and decoding the mating behavior of the Scylla serrata crab, the resulting research aiding in the development of a productive crab farm, including its profit-making potential, and the prospect of transforming the Salton Sea into a giant fish farm in California desert landscape. Successful experiments with crab ponds in the studio at UC San Diego led to trials with backyard ponds in the Los Angeles suburbs, and then to designs for large-scale gravity-fed ponds in the Coachella Valley, which would accommodate a large population of crabs, algae, clams, and mussels; a so-called “polyculture system” as described in the Fourth Lagoon.

While making what Newton called “this megalomaniacal design” for their large-scale fish farm, the Harrisons also developed a firm argument against the monoculture paradigm dominating the Coachella Valley and leading to the poisonous condition of the Salton Sea. The Fourth and Fifth Lagoons imagined the transformation of the Salton Sea into an estuarial lagoon, enabling it to support a large-scale crab population. The design aimed to decrease the salinity and pollution of the Salton Sea by cutting an input-output channel from the Salton Sea to the Pacific Ocean and through the Colorado River delta to the Gulf of California. However, the artists soon discovered that it would lead inadvertently to substantial pollution of the Pacific Ocean. Thus, they ended the hypothetical experiment, concluding that it was an unethical project to carry out, and it was never developed beyond the design stage. At the heart of the Lagoon Cycle lies the quintessential argument about the cost of belief. “How much does it cost to believe in something?” the artists ask. “If I believe in boundless resources, then the cost of that belief is the death of our ecosystems.” [6] The Fifth Lagoon raised the important question as to who would flush the ocean pollution resulting from the outflow of the Salton Sea. The Lagoonmaker and Witness, speaking for the Harrisons, lament in one voice the deadly and catastrophic long-term outcomes of such mega-technological solutions.

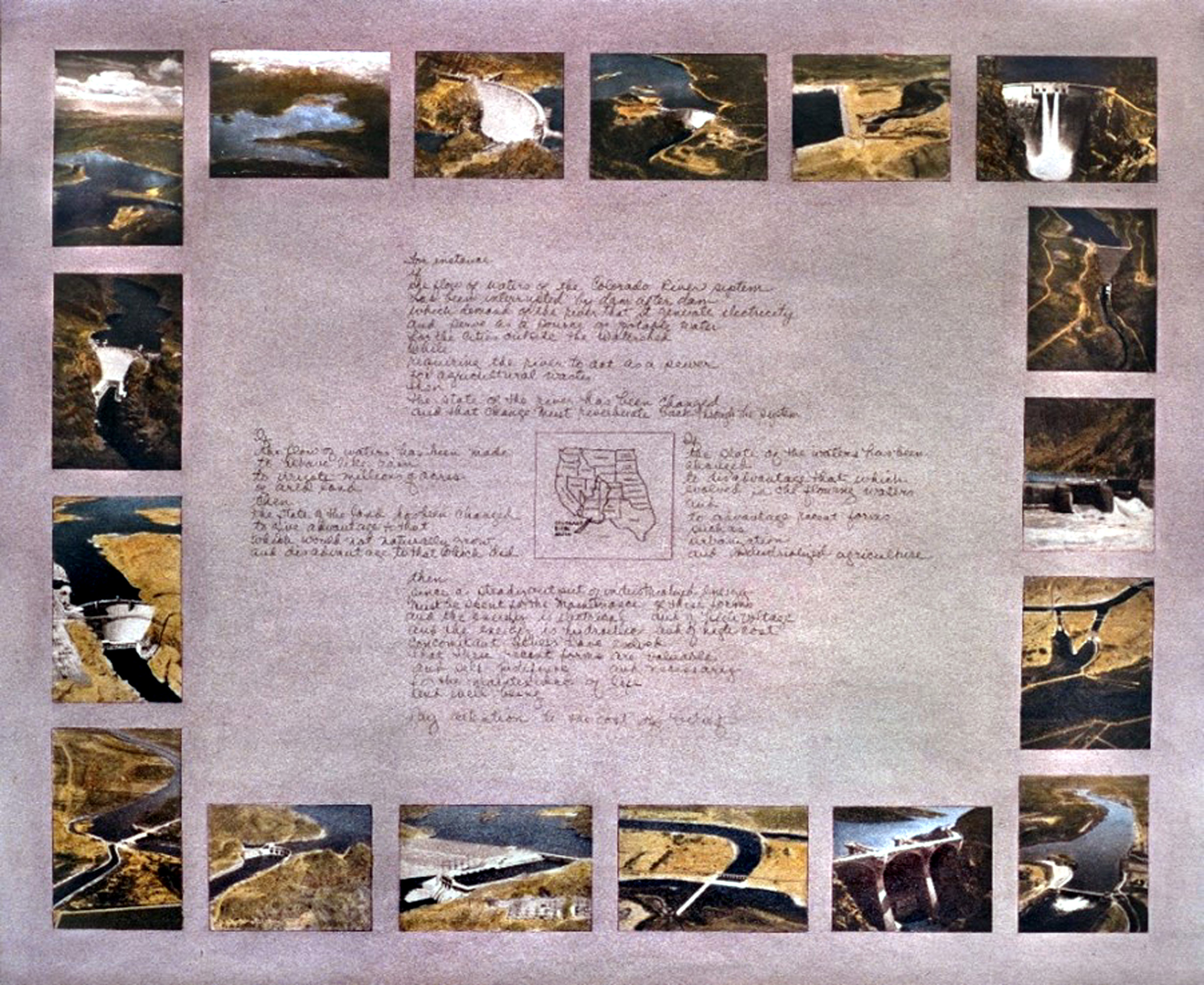

Through such empathy for the environment, the Lagoon Cycle visualized catastrophic outcomes of the vast, evolving system of resource extraction that has led to environmental degradation and the climate crisis—the central theme of all the Harrisons’ later investigations. Exploring the Colorado River watershed and its water uses and policies, the Sixth Lagoon demonstrated that the river system did not fare well, as it was dammed and re-dammed and its ecosystems marginalized compared to the river systems in Sri Lanka, starting point for the Lagoon Cycle. As with their previous Lagoon phases, the Harrisons engaged satellite and bird’s-eye view photography, hundreds of pages of scientific reports, and their own hand-drawn sketches of the whole river system. The results would then be presented poetically by the Lagoonmaker and Witness, who testify again in one voice:

For instance,

if

the flow of waters in the Colorado River system

has been interrupted by dam after dam

which demands of the river that it generates electricity

and serves as a source of potable water

for the cities outside of the watershed

while

requiring the river to act as sewer

for agricultural wastes

then

the state of the river has been changed

and that change must reverberate back through the system…

Pay attention to the cost of belief.

Its large-scale painted murals combining maps, designs, photography, and poetic texts, the Lagoon Cycle developed a completely new understanding of lagoons and watersheds as extremely endangered ecosystems. The cycle concludes with a prophecy of the future existence laid out in the Seventh Lagoon. After decoding lagoons, watersheds and their state of existence, the Lagoonmaker and Witness recount a dream the Witness had: Earth has warmed, all ice has melted, the oceans have risen, and ecosystems and civilization alike are under stress. As before, the Lagoonmaker and Witness speak in one voice:

And in this new beginning

this continuous rebeginning

you will feed me

when my lands can no longer produce

and I will house you

when your lands are covered with water

and together we will withdraw

as the water rise.

If we achieve this

then the oceans rise gracefully

we can withdraw with co-equal grace.

The Lagoon Cycle, a monumental, 49-meter-long mural in sixty parts, set out the Harrisons’ argument about the interconnectedness of ecology and the economy. They began to work on an even larger scale, introducing bio-regional thinking and planning while discussing honestly the consequences of the vast, technologically enabled exploitation of natural resources effectively leading to a widespread ecocide. Finished in 1984 through a leap of intuition and imagination, the Lagoon Cycle goes on to imagine future ecologies while prophetically concluding that climate change and global warming are inevitable.

Expanded Strategies, Collaboration with the Life-Web

After addressing global warming on a planetary scale with San Diego as the Center of a World and the Lagoon Cycle, the Harrisons further expanded and advanced their prophetic vision of rising temperatures and sea levels with Tibet is the High Ground (1993, 2007), Endangered Meadows of Europe (1996), Greenhouse Britain (2000-2007), Peninsula Europe (2000-2007-2012), and The Bays at San Francisco Become a 162,000-hectare Estuarial Lagoon (2007). These regional examples comment on the catastrophic effects of climate change in different ways and suggest various scenarios to ameliorate the consequences locally, as well as ways to enact short- and long-range planning for life adaptation. Visualization of climate-change data lies at the heart of all the Harrisons’ investigations, driven by the audacity to practice eco-conscious imagining beyond scientifically controlled experiments. Their process of appropriation, reconfiguration, and reinterpretation of scientific data adds a fresh dimension to environmental knowledge because, as Roger Malina observes, “new knowledge is co-created.” [7]

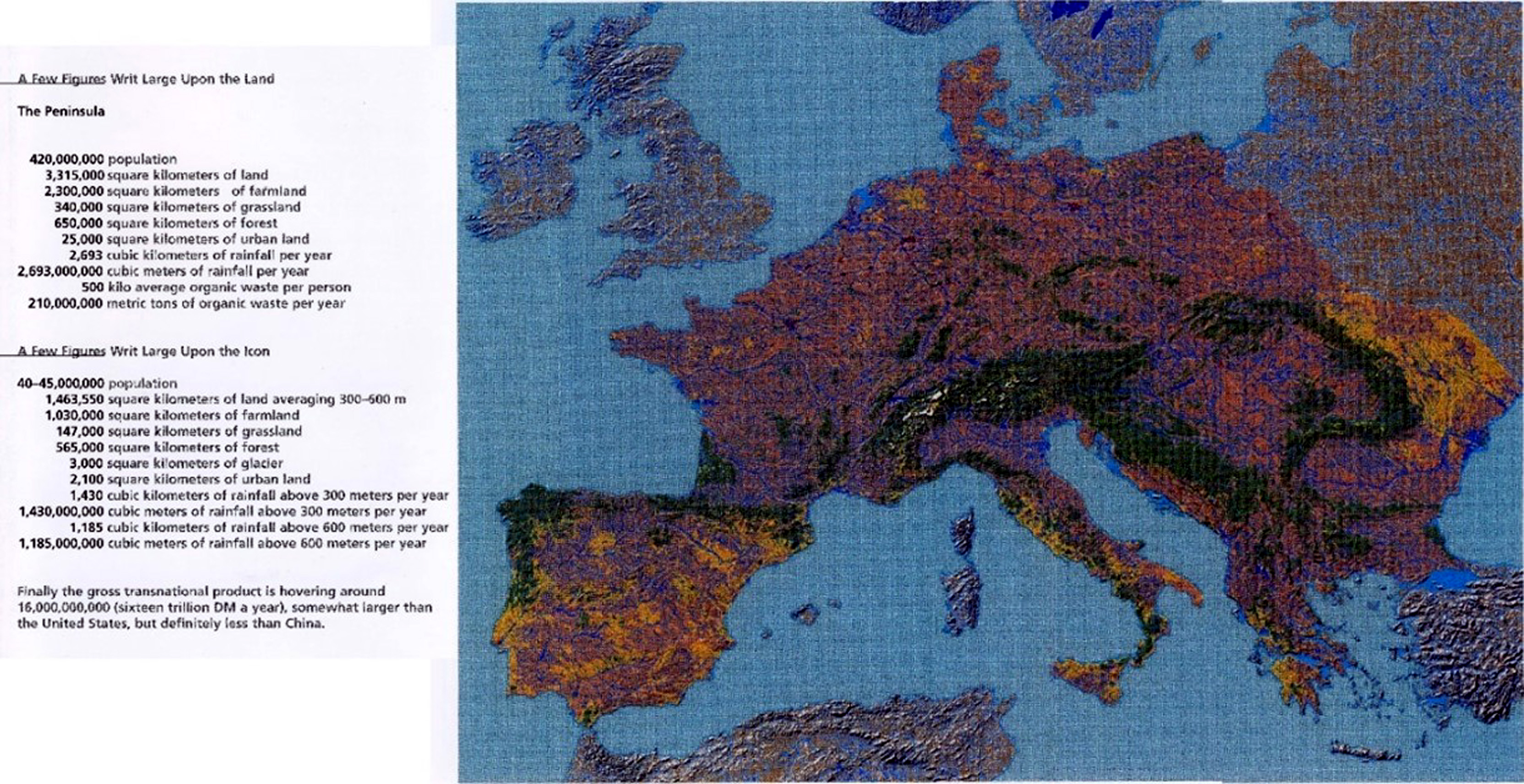

Peninsula Europe (2000-2007-2012), a monumental multi-part work exhibited internationally in Germany, France, Holland, and the United States, was revised several times and proposes a large-scale, real transformation of the entire European landscape by means of re-terraforming the land to hold water as it once did naturally. The work addressed wide-ranging issues, from predictions of the loss of land due to ocean rise, to the upward migration of species and people, to the loss of farmland due to extreme drought. Peninsula Europe I or The High Ground Bringing Forth a New State of Mind (2000-2007) starts by imagining Europe without political divisions, as a unified landscape marked by mountain ranges and watersheds. Designing a body of watersheds, the Harrisons invented a unified map of Europe susceptible to climate change and proposed the regeneration of its highlands to secure ecosystems and water supply:

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its river systems, estuaries, ocean edges,

forests, wetlands, meadowlands, and eco-corridors

are values sufficiently

and enables to co-join

into a complex biodiverse life web

self-sustaining in nature

an eco-net of the whole

and its high ground, grassland, forest communities

contribute ecological redundancy, continuity, and mass

at a continental scale…

Entityhood happens when each parts feeds value to the whole

and the whole complicates itself

following the natural laws of self-organization

and creating a complex entity.

The proposal visualized “a needed transformation” of highlands in Europe with its “relative openness of terrain in the high ground and a relatively low population,” as “the system shock causing glacial melt requires a co-equal effort on the part of civilization to assist the upward migration of species in such a manner to counter the negative impact of the glacial melt and the absence of snow melt.” [8]

To re-energize topsoil, they envisioned creating a multitude of small catchment basins to act as water-percolation systems for aquifers. In this scenario, the topsoil would become a water-holding sponge, normalizing the water cycle.

In collaboration with mapmakers at Act’Image in Toulouse, the Harrisons visualized a 96,000-square kilometer loss of land if water levels were to rise five meters, with twenty three million people having to move inland. Another calculation involved the most accurate weather predictions for a drought moving across Europe from Portugal to Central Germany. A third scenario accounted for a disproportionate rise in temperatures, acceleration of glacial melt, and decreased snowfall. A fourth scenario investigated the change of 2.4 million square kilometers of farmland affected by drought. The work was primarily concerned with what to do in response to such circumstances.

From Peninsula Europe IV:

Are the conditions in place yet

That require a bold experiment

At unprecedented scale and cost

And with unpredictable outcomes

For instance, out of 2.3 million square kilometers

of farmland

20 percent probably, possibly much more

Will yield to drought

Out of 650000 square kilometers

Of mostly monocultural forest

80 to 90 percent will yield to fire, disease, flood,

and drought

in the high grounds

With the predicted 5.5 degree Celsius temperature rise

Out of 340000 square kilometers of grassland

Typically monoculture

30 percent will yield to drought

As 450 million people become 500000 million

And waters rise

Forcing the upward movement of people

And as food production drops

And markets are harshly stressed

If business continues as usual

The best likely case is food rationing

The worst case in many places

Is the collapse of civil society.

These scenarios seriously considered both the impact of global temperature rise and a solution to drought, remediating it with water-retaining landscapes—tangible examples of the kind of re-terraforming strategies that, in Newton’s words, would allow the human race to meet nature halfway. Peninsula Europe Part IV envisioned real transformations of the shape of the earth and of farming methods across Europe. The Harrisons’ concept also suggested a vast research effort that would look at species and ecosystems inhabiting the future hot zones of the planet and investigate the assisted migration of species to adapt to “a very different world than we now inhabit.” This proposed methodology was twofold: collaboration with a natural system’s well-being and the invention of food-production systems by which the harvest preserves the system and the system preserves the topsoil.

Peninsula Europe addresses in earnest the global warming phenomenon, now growing at an exponential rate, and proposes mechanisms for how to cope with it by transcending national borders, by employing bioregional thinking, and by inviting a new state of mind or culture shift. Examining the Harrisons’ call to action, Eleanor Heartney observes that the artists’ set of prescriptions, comprising “the drastic reordering of human society and the typical landscape along the lines of the agency of nature,” are the only reasonable response.[9] She also observes that their approach was vastly different from many other examples of ecological art, ranging from technological and engineering fixes to the substitution of barren nature with artificial environments, and to admirable yet small-scale efforts at land reclamation, sustainable farming, recycling, and other gestures. The Harrisons proposed to use complex systems thinking. They would treat nature as self-complicating, self-renewing, and self-continuing, a living partner to humans—thus the Web of Life—rather than a mechanistic, deterministic entity with no agency, an object of human progress grounded in prevailing narratives of the Western scientific revolution, focused on the triumphant subjugation and exploitation of the natural world.[10] The Harrisons’ scenarios can be called utopian dreams, as a huge economic and social cost is attached to them, yet many of their proposals offer ideas on how such global-scale initiatives could be financed by giving back to the Life Web and by forming a partnership with nature. However, this requires political and social unity to join in a vast common cause. Thus, the eco-futures they described were full of hopeful idealism, as the Harrisons believed in the possibility of inventing a new culture, a new civilization. [11]

Peninsula Europe I concludes:

Reflecting on Big Numbers

Refusing to Be Intimidated

Looking for a Middle Way

Reflecting

on fragmentation and the conditions for unity

on the health and well-being of the high grounds

and the life web

reflecting on the will of civilization to fragment

when its survival

and that of ecology upon which it depends

require certain unities

reflecting on reframing the conversation

by which culture recreates itself

movement by movement…

The Bays at San Francisco (2007) was another pivotal work that addressed a scenario in which global warming set local waters in motion, turning dry land into kilometers of fringing marshes. As the sea level rises, tides and tidal surges activate, causing San Francisco Bay to expand and flow through the Central Valley, reaching Sacramento within 100 years. The Harrisons said that this three-meter ocean rise would generate a 162,000-hectare estuarial lagoon. They asked, “Who was going to take responsibility for assisting a viable ecosystem to form?” They argued that an active method of re-terraforming was needed rather than leaving this vast occurrence to chance. The Lagoon Cycle argues that such places are rich in life yet fragile, so a scientific team could, in the Harrisons’ words, assist in “giving birth to the estuarial lagoon” of a future San Francisco. The Harrisons asserted that a rise in sea level of three meters, alongside rising temperatures of three to four degrees, would result in a productive ecosystem; polyculture on the shores of the lagoon could be established with the economic opportunity to produce an abundance of seafood in a low-intensity fish-farm scenario. The Harrisons maintained that paleo-botanical research could reveal what thrived in the distant past, when both temperature and sea level were higher, and thus could assist in forming the lagoon as a “self-continuing, self-complicating and self-growing” environment.

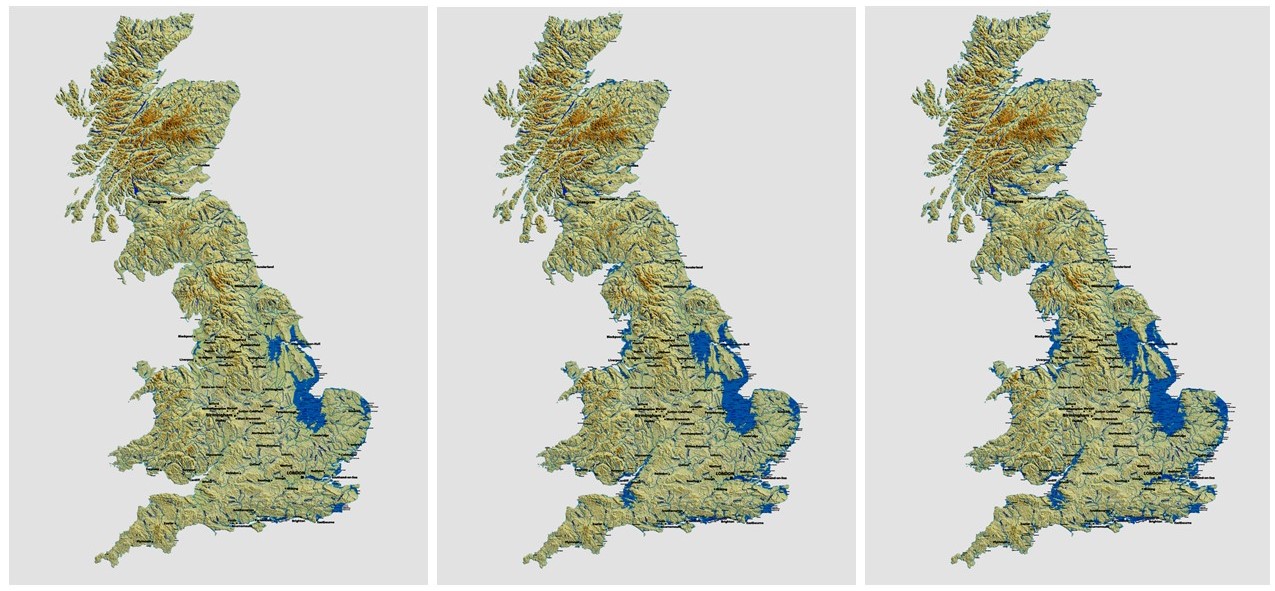

The Bays at San Francisco offers an unexpected look at the incredible pressure climate change puts on all ecosystems and how it threatens human existence. The Harrisons pose the question, “Can we adapt to this scale of change in a way that benefits a changing culture while collaborating with an evolving ecosystem?” The answer is surprising: exergy, defined by the Harrisons as the raising of the available energy in a system to do necessary work. If exergy were combined with human creativity, the resilience of ecosystems could be restored, and entropy and energy could be regulated and re-balanced in collaboration with the Web of Life. Designed for a lecture series by invitation from David Haley, and in collaboration with Chris Fremantle and Gabriel Harrison, Greenhouse Britain (2005-2008) offered yet another vision of how the United Kingdom would be affected by accelerated global warming. Three different scenarios of 5-meter ocean water rise, 10-meter ocean water rise, and 15-meter ocean water rise show how long-range planning could assist in the upward migration of the population. The exhibition displayed maps that show disappearing lands ranging from 10,000 square kilometers covered to 31,200 square kilometers covered, displacing potentially billions of people. The projections and accompanying texts educated the audience about the implications of water rise, surges, and storms, and the need for long-range planning.

A side project of Greenhouse Britain investigated the possibility of defending the city of Bristol from ocean rise and storm surges, while also proposing a controlled system of upward migration of the population to a new kind of settlement called Sky Gardens. Developed in collaboration with the architect John Bignell of the Bristol firm APG, Sky Gardens was envisioned as a complex of 71 skyscrapers designed to house 750,000 people from the area that would now be underwater. The sky dwellings were imagined as “ecologically provident and culturally appropriate,” with complex organizational patterns of interlocking systems of residences, gardens, and walkways accommodating vertical promenades, funiculars, and elevators that would encourage cultural encounters and new relations between “people and people, people and places, and places and places.” [12] Sky Gardens served as the model for the Harrisons’ eco-civility, which challenged the classical modernist vision of big box buildings that “normalized the social alienation” while also proposing a bold vision for the successful coexistence of intense population density and complex biodiversity in the face of a climate change crisis. [13]

The Harrisons’ proposals and designs for global warming not only educated audiences about its horrific implications “because news is not good and only getting worse,” but also invited and ignited transformative thinking about human adaptation at great scale. Newton said that transformative thinking is exciting and works of art are inherently transformative. The Harrisons insisted that art can change the world for the better—not just by enriching the life and spirit of those who love it but by proposing new solutions to problems revealed through an artist’s way of seeing combined with science, engineering, and social critique. Their ideas of the agency of art overlapped with what British social anthropologist Alfred Gell held, namely that “visual art objects are not a part of language . . . nor do they constitute an alternative language” and thus should not be treated simply as illustrations or visual texts. Instead, Gell argued that artworks were tangible indices of social interactions and acted as social agents. [14] The Harrisons’ commitment to the Web of Life, which they labelled, rather bluntly, a Dictatorship of the Ecology, led them to produce works of art that could act as just such social agents to reshape the world in which we live. [15]

Work of Art as a Cross-Disciplinary Re-Terraforming Practice

First encountered in the Lagoon Cycle, the Harrisons’ prophetic vision of rising sea levels and global emergency was further advanced over the years in the Force Majeure series of works. The Harrisons recognized that on the deep time scale of evolution, humans were a relatively recent phenomenon and that our species’ reign on Earth inevitably had an expiration date, just like all other dominant species that had come and gone before us. [16] Therefore, new strategies of adaptation and survival were needed. A series of works entitled Future Garden speak to the Harrisons’ hope of saving the planet in the face of the crisis posed by climate change and its threat to Earth’s many ecosystems. Exemplified by the Garden of Hot Winds and Warm Rains (2003), Tibet is the High Ground (2007-12), Sagehen: A Proving Ground (2007-ongoing, in the High Sierras near Tahoe), and the Future Garden for the Central Coast of California (2018-ongoing, at the Arboretum at UC Santa Cruz), the Harrisons used drawings, large-scale maps, phototext panels, photographs, and conceptual design proposals to address adaptive responses to the pressure on planetary systems, negatively impacted by industrial processes as global warming accelerates.

The Force Majeure works laid out a new framework for an ecological artistic practice in the Anthropocene, when the pressure of human-caused global warming on all planetary systems is alarming and frightening. The Harrisons adopted the legal term “force majeure,” which refers to circumstances that are beyond the control of the parties involved in a contract, to describe the state of the planet when they set up the Center for the Study of Force Majeure (2007-present) at UC Santa Cruz. As co-directors of the Center they collaborated with small teams of biologists, climate scientists, urban planners, and other experts to redesign culture in anticipation of global environmental events—rising waters, storm surges, shrinking coastlines, and immense forest fires—that set off corresponding human disasters. The Harrisons showed that concerted efforts and vast research must be invested in the design of future ecologies that would be able to function in new temperature regimes and ecosystem conditions.

Future Garden is a series of proposed solutions that anticipates major planetary events and demands corresponding adaptation. The Harrisons developed a series of counterproposals to what was projected to happen as a result of rising temperatures, the loss of the snowpack causing extreme drought, and other abrupt changes to environmental conditions. Essentially, these proposals involved re-terraforming, through the assisted migration of species to higher altitudes and latitudes and through experimentation with species better able to adapt to hotter temperatures in the future.

The Future Gardens

A growing body of work

addressing a new frontier

A heat wave touching all surfaces

Everyplace, everywhere, everything

That is growing is changing

As temperatures warm

That which grows must move elsewhere

Or fade from existence

Yet everyplace, everywhere

At one time or another

has warmed or cooled or burned

Always there is opportunity

In fact, Every place

is the story of its own becoming.

Where Every Place is the Story of its Own Becoming

Simply put

Where ecosystems fade

unable to continue

Unable to maintain coherence

In the face of rapidly rising temperatures

A question is asked and then answered

Is it possible to propagate the future ecosystem

The future grouping of species that will self-complicate

And introduce it

Even as the existing system fades from stress

So rapidly assisting migration

That hundreds, even thousands of years

Work by the life web to reassert itself

are collapsed into decades.

(From the Harrison Studio Archive)

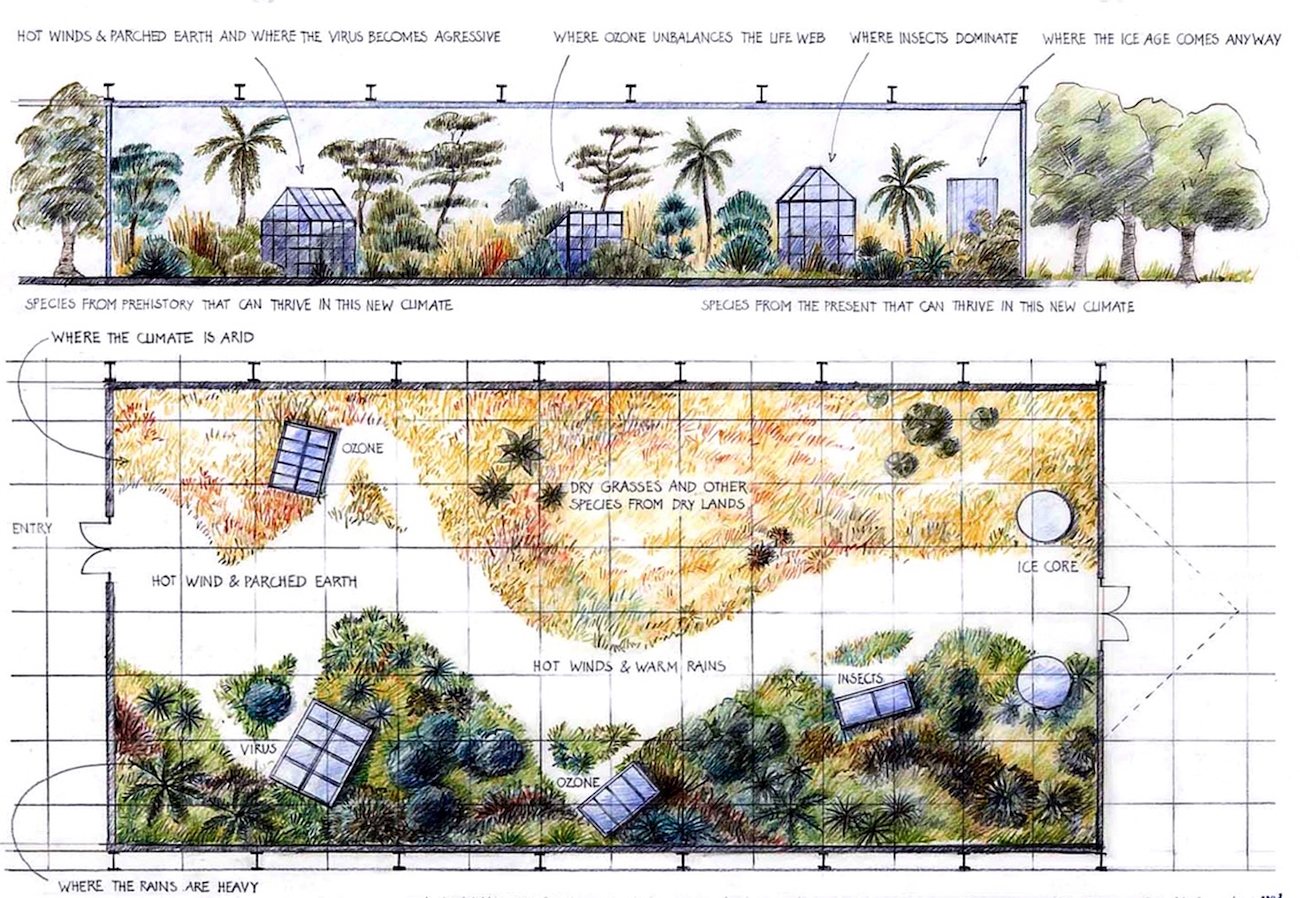

The Garden of Hot Winds and Warm Rains (2003) was the first Future Garden developed as a conceptual design of the greenhouse space for Endangered Meadows of Europe (1995-98), when the Harrisons were invited to work on the famed rooftop garden at the Ausstellungshalle Museum in Bonn. The Harrison Studio transplanted a 400-year-old meadow that was being replaced by an urban development and told the story of the meadows and their value as models of cooperation between human needs and a bio-diverse habitat. [17] Structures were erected on the path of the grassland that surrounded the meadows to contain a series of fifteen complex and many layered stories in German and English, along with images of the fifteen meadows. Working on meadows, the Harrisons proposed a greenhouse based on paleo-botanical research that forecast what would live in the region if the temperature rose three degrees Celsius. Although unrealized due to its high cost, the design explored a future ecosystem envisioned as a landscape warm and dry on one side but warm and wet on the other. Completed parts of Endangered Meadows brought to life issues of biodiversity and inspired planting A Mother Meadow for Bonn, created with the seeds from the rooftop garden. Later designs envisioned an interdependent system of arid and humid gardens that would model the production of food for future consumption. However, this design was radically different from modern-day industrial practices, as it planned a harmonious eco-cultural collaboration between human cultures (civilizations) and the cultures of nature (the Life Web), leading to a future no longer based on extraction but on practices of production that sustained rather than depleted interdependent ecosystems.

Newton Harrison called Endangered Meadows the first step in developing the body of work he called Future Garden and, in his interviews, often reflected that it was “an aesthetic experience and a scientific product as well.” In the catalog for the Endangered Meadows, he wrote that “artists do, in fact, mainly work intuitively, often in a state of not knowing, or almost knowing. Therefore, it is not possible or even desirable to know full implications of a work until considerable time has passed. In other words, the process of art making guarantees that the artist will not know the full content of what he or she has done. This is what is meant by working at the edge of awareness. Therefore, retrospective analysis often enriches future work.” [18]

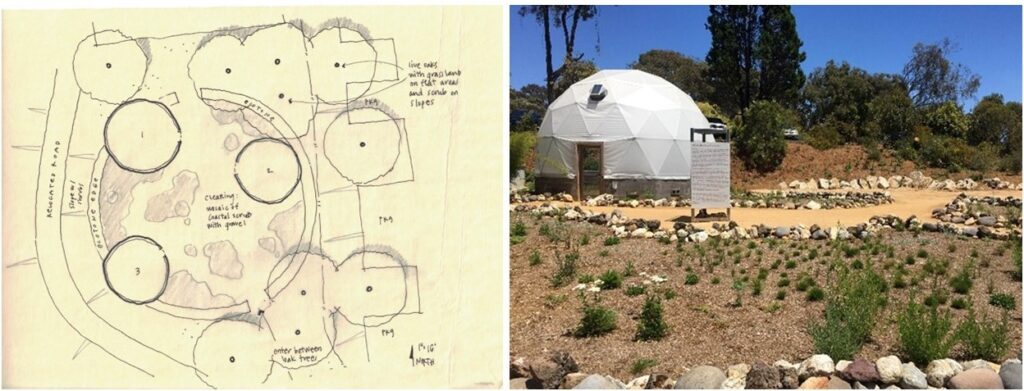

Sagehen: A Proving Ground (2007-present) exemplifies a fully developed concept of Future Garden that considers the upward migration of species. A multi-generational fifty-year collaborative endeavor to conduct research in the Sagehen drain basin of the Central Sierras, the project addresses whether there are available ecological responses that will in some measure replace the value once provided by disappearing glaciers and snowmelt to river systems and dependent ecosystems and human cultures. It models the implementation of a simplified first-succession ecosystem intended to follow the glacier as it retreats. The project involves physically moving groups of plant species like wild rose and red fir to higher ground, with the aim of helping the seedlings become resilient both to the warming effects of climate change and to living at different altitudes. By testing the ability of a representative group of plant species (the “resilience ensemble”) to survive heat, drought, flood, and altitude variation, the initial experiment has been successful, the ensemble enduring harsh conditions yet showing promising growth.

Conclusion

As Roger Malina so precisely observes, these projects translated climate change data not readily accessible to the human senses into new linguistic, visual, and sensory vocabularies that are universally understood.[19] Future Garden and other works in the Force Majeure series called for a new form of cross-disciplinary activity to anticipate major planetary events and demand preparation. The Harrisons proposed going beyond observation and analysis to implement local initiatives aimed at alleviating the consequences of climate change by allowing any ecosystem to remain a viable host for terrestrial life. Working collaboratively with scientists, the artists would now assume a new kind of agency as “landscape artists” or “planetary gardeners,” in Anne Whiston Spirn’s words, or re-terraformers, responsible for the mitigation of species, creation of succession ecosystems, and the reorganization of human settlements. [20] The Harrisons called audiences to question the limits of artistic agency, inviting viewers to contemplate the greater possibilities of an artwork: as a work of cross-disciplinary science, as a work of preemptive bioregional planning, and as an act of re-terraforming that is more than simply an unrealizable metaphor in the face of ecological extinction. The Harrisons’ work pioneered a unique form of eco-futurism that stretched not only the methodology but also the content of art and science, assuming an entirely new ethical dimension while contributing to the active production of knowledge.

The Harrisons’ work addressing the implications of climate change will be prominently featured in Helen and Newton Harrison: California Work, Getty Pacific Standard Time, Art + Science 2024. The exhibition will highlight their diverse artistic approaches and the affinities between their wide-ranging art projects and science. It will be presented at four venues: La Jolla Historical Society, California Center for the Arts in Escondido, Central Public Library San Diego Art Gallery, and Mandeville Art Gallery at UC San Diego. [21]

Tatiana Sizonenko is an art historian and award-winning curator working across the Renaissance, Modern, and Contemporary periods. She received her Ph.D. in Renaissance art history from the Visual Arts Department at UC San Diego while also developing expertise in contemporary art. Ms. Sizonenko currently serves as the project curator for Helen and Newton Harrison: California Work at the La Jolla Historical Society, a project funded by Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time, Art + Science 2024. She is the recipient of several fellowships including the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories Fellowship. In 2017 she was named Environmental Fellow of John Muir College at UCSD for her curatorial work on the exhibition Weather on Steroids: The Art of Climate Change Science shown at the La Jolla Historical Society. Ms. Sizonenko has curated, organized, and installed several dozen exhibitions, coordinated and prepared several exhibition catalogues, and published catalogue essays and peer-reviewed articles in the United States and in Russia. Ms. Sizonenko is also Art History faculty at CSU San Marcos and the Design Institute of San Diego, teaching courses on art and architecture from ancient to contemporary.

Notes

[1] In several interviews with the author conducted in 2021, Newton Harrison talked about the Life Web. Also see the published interview with artist by Oliver Kupper in Autre: Oliver Kupper, “Force Majeure: Pioneering Eco-Artists the Harrisons Created a Survival Guide for a World Careening Toward Disaster,” Autre, Issue 13, F/W (2021), pp.250-257.

[2] Edward Shanken, “Tipping the Scales: The Harrisons and the Force Majeure,” Rydell Visual Arts Scholars, 2016-17, Exhibition Catalogue (Santa Cruz: Community Foundat ion Santa Cruz County, 2017), pp.24-41, 24.

[3] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, Edited and Designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke, Essays by Anne Douglas & Chris Fremantle, William L. Fox, Eleanor Heartney, Roger F. Malina, Paul Mankiewicz & Dorion Sagan, and Anne Whiston Spirn (Prestel, 2016), p. 323.

[4] The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, pp. 50-53.

[5] Ibid., p.53.

[6] Kupper, “Force Majeure: Pioneering Eco-Artists the Harrisons Created a Survival Guide for a World Careening Toward Disaster,” pp.254-255.

[7] Roger Malina, “Force Majeure: Performing the Data of Climate Change,” in Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, Edited and Designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke, pp. 447-450.

[8] The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, p.316.

[9] Eleanor Heartney, “Dancing with the Waters: Helen and Newton Harrisons’ Call to Action,” in Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, Edited and Designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke, pp. 443-446.

[10] Eleanor Heartney compares the Harrisons’ holistic approach to nature that aims at restoring its balance to Carolyn Merchant’s critique of mechanistic assumptions about the natural world stemming from the patriarchal order. Merchant, a historian of science, challenges the valorization of the Scientific Revolution and links it to the replacement of an organic female-centered vision of nature by a mechanistic, patriarchal order organized around the exploitation of natural resources. Merchant wishes to revise the paradigm of domination and exploitation of both women and nature, a common theme of activist and ecological art that relates to the Harrisons’ ideal. See: Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature (San Francisco: HarperOne, 1990), p. 69.

[11] Kupper, “Force Majeure: Pioneering Eco-Artists the Harrisons Created a Survival Guide for a World Careening Toward Disaster,” p.256.

[12] The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, p.353.

[13] Ibid., p.351.

[14] Alfred Gell, Art as Agency. An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), p.6.

[15] The idea of the “dictatorship of the ecology” first appears in the Harrisons’ thinking during their work on the Meditation on the Great Lakes of North America (1977). They wrote a semi-poetic text in which they urged “the citizens of the watersheds of the Great Lakes of North America to withdraw from Canada and the United States and generate a Dictatorship of the Ecology, for reasons of survival (of both ecosystems and cultural systems).” The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, p.65.

[16] Kupper, “Force Majeure: Pioneering Eco-Artists the Harrisons Created a Survival Guide for a World Careening Toward Disaster,” pp.252 & 257.

[17] Endangered Meadows of Europe is described on the Harrison Studio website, https://theharrisonstudio.net/endangered-meadows [accessed, March 2, 2022].

[18] Quoted from the interview in: Mrill Ingram, “Ecopolitics and the Aesthetics: The Art of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison,” Geographical Review, Vol. 103, No. 2 (April 2013), pp.260-274, p. 272.

[19] Malina, “Force Majeure: Performing the Data of Climate Change,” p. 447.

[20] Anne Whiston Spirn, “Helen and Newton Harrison: The Art of Inquiry, Manifestation, and Enactment,” in Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years, Counterforce Is on the Horizon, Edited and Designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke, pp.434-438.

[21] To learn more about the exhibition, please follow us on the Web: https://lajollahistory.org/exhibitions/helen-and-newton-harrison-california-work/