Chances, Limitations, and Conditions of Ecological Art: Three European Projects by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke

Nature and art cannot be separated without destroying art and life. Nature cannot be understood without the arts.

This quote by the German national poet Goethe reflects in principle the concept of ecological art: 1) The purpose of art is not to serve, but to maintain a significance of its own—without it, we cannot understand nature. 2) The purpose of nature is not to inspire artists—without it, however, art is hardly possible. 3) Nature and art are mutually interrelating, thus forming the basis for new perceptions of the life web.

Alexander von Humboldt, the great 19th century holistic thinker who is still and increasingly influencing our concept of understanding the universe with the planet earth considered the arts as important as the sciences for communicating the central issues of human relationship and interaction with nature. “Everything is interrelating,” as Humboldt phrased it, and this interrelation includes ecosystems as well as natural sciences, ethnology, information technology and architecture.

The diversity of the disciplines involved in ecological art brings about a variety of different people with different knowledge, perspectives and approaches to collaborate. This actually provides the basis for perceptions and results which an isolated individual could not generate. Being rather unusual in the traditional arts and sciences (unless interdisciplinary), such team-oriented collaboration enables scientists to think beyond their narrow-minded subjects and artists to consider natural laws, phenomena, data and analyses. Consequently, eco art is not exclusively addressing the world of the arts, but all human beings.

Since nature or the life web is not the result of human design, it may not be constructed or deconstructed like a building structure. Therefore, eco art implies a constant change in the concept, the flow of work and the direction of its outcome; integrating new findings and possibly leading to unexpected and surprising results. Artists are able to apply the technique of collage by ‘scanning’ a subject, determining its numerous aspects, associating one with another, regrouping and changing the interrelations until an adequate, complex and practically applicable narrative results. This almost automatically counteracts the under complex and mechanistic traditional engineers’ way of thinking that there is no problem that human ingenuity and technological advancement can’t solve, even if problems are concerned that are caused by this very concept.

It has become an essential knowledge that nature represents the mirror image of humankind: It is impossible to protect that which we call nature or the life web from the devastations of climate catastrophe and excessive profit-seeking if we don’t understand that the nature we fear to loose is actually our own nature. The following three examples of European projects by the Harrisons shall illustrate how target groups from the arts, sciences, culture, education, politics and society in general can be involved.

The first example, Endangered Meadows: Future Garden 1 was realized starting in 1996 at the then recently established Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn, one of the largest and most prestigious museums in Europe and at that time the showcase of national German art policy. Its claim had been to develop and represent a modern concept of a museum as compared to the traditional 19th century mission of culture preservation and higher education. This and the fact that the emphasis is shifting from visitors passively enjoying and studying art to active immersion, experiences, discoveries and conclusions made it the perfect place for eco art.

As a cultivated part of the European landscape, meadows are profoundly diverse. Since an increasing number of agricultural areas are being maximized with regard to productivity or turned into building sites, meadows are one of the most endangered biotopes. A 400 year old meadow from the Eifel area nearby, which would have otherwise have been destroyed, was instead rolled up, transported to Bonn and unrolled on the museum’s roof to cover a surface of 6,000 square meters; other endangered meadows from the vicinity were also utilized.

Over the course of one year, the Harrisons installed the Eifel meadow, a wet meadow, and a stone meadow. Collectively, these meadows contained 164 species of plants, where normally there would be 30 to 35, among them several from the red list of endangered species. As time passed, insects such as various rare bees, bumble bees and butterflies as well as birds moved in or visited. Human visitors could clearly determine the different types of meadows by their visual appearance, but also by the fauna inhabiting them. The Harrisons designed a perimeter walk of normal grass, that means lawn, about two meters wide, with 14 fence structures for sitting. Each one included a wooden book-like form; by turning the plywood page the visitors could read the English or the German version of a text. Each one featured a different meadow story and an image of a particular meadow—one from Sicily, another from Spain, another from Sweden, and so on. Thus it became clear to the visitors that endangering meadows as a biotope is not a local but a European topic. Whereas the perimeter walk of normal grass dried up during the summer months, the different parts of the Future Garden were growing without irrigation and protection against the wind. A stable biotope had developed. The plan to create an awareness of meadows as an endangered ecosystem and cultivated landscape had proven successful. More than 250,000 people visited the roof top meadows over a period of two years; many of them returned frequently, experiencing the development and changing appearance of the meadows. In addition to those traditionally associated with the museum, people came who usually don’t visit museums–the numbers of families with children and school classes were unusually high. The accompanying activities like lectures, discussions, workshops, guided tours, concerts and a conference were extremely well accepted and attended. Public advertisement and information were accomplished by posters, leaflets, brochures, mailings, newspaper/magazine ads, TV/radio, film/video, internet etc. This enabled the museum to reach very different target groups, and provide information about the roof garden even to those who did not buy the catalogue or attend the exhibition.

An aspect to be mentioned is that Future Garden 1 was developed in close collaboration with lecturers and students of Bonn University, the Botanical Garden and the Botanical Institute—all of which took part in all further development stages of the project. Profound support was achieved from political bodies like the City of Bonn on the local level and the European Cultural Heritage Foundation as a supranational organization. Angela Merkel, who was then Germany’s Federal Minister for the Environment gave the opening speech. Several activities with emphases beyond the exhibition and the museum were offered while the project lasted and continued thereafter. A mailing campaign informed schools and other interested institutions, groups and individuals how to receive project descriptions and instructions about creating an individual meadow biotope including seeds. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition was printed climate-neutral on recycled paper and came in a box which contained not only the book but an envelope with a selection of seeds thereby expanding the effect of a mere print medium and spreading the conceptual and physical essence of the meadow. The mayor of Bonn caused the seed campaign to be introduced to other cities in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate. A permanent installation was opened at the Rheinaue, Bonn, in 1997 under the title A Mother Meadow for Bonn: Future Garden 2, also by initiative of the mayor of Bonn and the city’s Parks Department. The roof garden of the museum had been mowed twice a year, so that hay and seeds could be harvested which were then applied to over 4,000 square meters of a meadow area along the Rhine which is also mowed two times a year. These hay and seeds were also applied to park areas in Bonn and its vicinity turning about 4,000 square meters into meadows. This process continues up to today. Thus, more and more recreation areas for nature and humans are being created, which are not only increasing the number of biotopes but may also be installed and maintained at reasonable costs.

The second example is a terraforming work which did not earn the success it would have deserved: The project A Ring of Many Floodplains for the Oder River resulted from theoretical considerations in France (which were not taken up by the local museums) and the Harrisons’ work at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, on the purification of rivers. It is an example for a totally convincing and price-winning concept publicly acclaimed by politicians, institutions like the state of Saxony Anhalt, environmental foundations like the Federal Bundesumweltstiftung and the media, but never considered for practical realization by the responsible authorities.

Against the common belief that floods were inevitable the idea was that wetlands could serve as new floodplains creating a displacement that would generate a new form of flood control, an array of nature reserves that were simultaneously water storage systems, purification systems, and parks. The idea was that building a ring of mini floodplains would, over time, cost less than the flood damage and could save lives and property. The Oder River, however, almost completely canalized and densely populated along the river banks, left no large areas within which the floodwaters could spread without damage. Therefore, the basic idea was to buy available land in spaces as close as possible to the place where the tributaries flow into the river, creating areas that can serve as small floodplains. This would save the money required for massive dikes along the Oder River, ending the danger and costs of heavy flooding while adding ecological and social value to place. From an economic perspective, it appeared that the cost of acquiring new floodplain lands in Czechoslovakia and Poland, and doing the appropriate design and the earth shaping technical and ecological operations altogether would cost about 30 to 35 times less than the funds required for repairing the damages caused by the last big flood.

In spite of its public attention and widespread positive response, the work remained an idea. Ironically, only a year later, in 2002, the region experienced its largest flood of the 20th century (and along the river Elbe, as well), causing damages even exceeding those estimates. And apart from the fact that the German Chancellor was reelected that year, because he had posed on TV with rubber boots on shifting sandbags, no consequences were drawn with regard to flood prevention and the convincing ideas of the Harrisons. A more recent and equally horrifying example is the flood in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate at the end of last year.

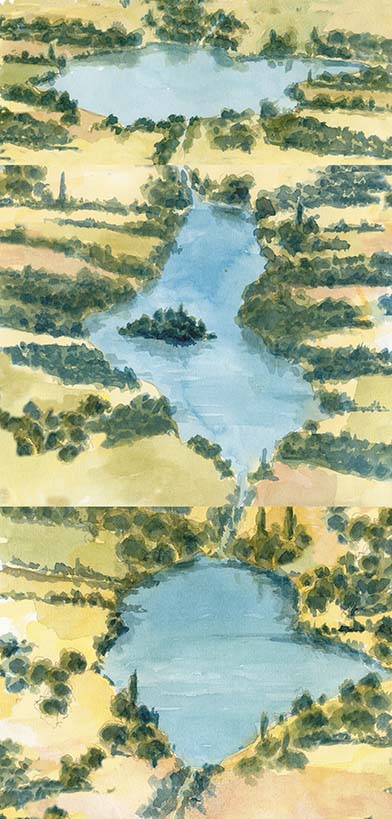

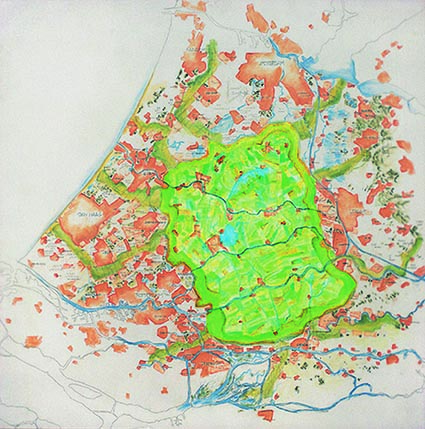

Our next example refers to successful terraforming: The Green Heart of Holland, an 800-square-kilometer area of farming that also harbored wildlife and 35 villages, actually embodying the whole history of landscaping in the Netherlands. This area had become the object of desire for many Dutch city planners. A 600,000 home community had been proposed, with apartment houses and infrastructure that would have effectively wiped out the properties of this area. As a consequence, wildlife populations such as fish and birds would have been decimated, topsoil lost, and culture disappearing with their users. A major part of cultural identity was about to disappear.

The Harrisons got into contact with the Cultural Council of South Holland which invited them in 1994 to find solutions. Among the many sites they visited and investigated in the Netherlands was the Naardermeer, the oldest nature reserve in the Netherlands which was in fact a very large polder or field that had gone wild. People were proud of the diversity that had appeared over time in this place, including storks from Africa and other water birds that had found it on their migration route. It contradicted the argument made by many planners, that there was no real ecological variety in the Netherlands.

The Dutch suggested on evolving what might be called an Open Studio. Once a week, one or another group of planners, architects, academics, museum people, and then planners again would spend an hour with the team in the studio, looking at the work the Harrisons were designing and offering insight and sometimes criticism. The public effect of such means of communication should not be under-estimated.

All together, participants developed a concept, which the Harrisons called the eco-urban edge and which had embedded in it a question: What is the best way for an urban continuum to end and ecological continuum to begin? Is there a way for this mutual beginning and ending to give advantage to both? The Harrisons proved that there was enough space to build the desired 600,000 houses, while still maintaining the great central park, the Green Heart, and keeping the city cultures separate. Moreover, the new residents who would occupy those houses would have about 140 linear kilometers of parkland. Everyone would be within minutes of the Green Heart or of a Green Heart extension. Furthermore, these linear parks were designed to reach out to an ecologically rich area so that species could travel between the Green Heart and a biodiversity ring.

Television debates were set up between the Harrisons and developers, there were newspaper articles and much publicity of any kind, and negotiations with a group of 45 mayors (who had come to support the work, understanding that the initial housing development would have buried their villages and their cultures). The subject matter, text, and imagery of the work developed by the Harrisons were given to the Minister of the Environment before an exhibition opened; the minister approved it. Elections were about to be held; the Green Party and several politicians of different parties included the work in their platforms. Then the right wing took over, and Green Heart Vision was cancelled. The work was widely exhibited despite the project’s cancellation.

Almost six years later, the conservative government had been voted out of office, the much more liberal government that had supported the work was re-instated and the project realized with some minor modifications. In 2002, the Harrisons were awarded the Groeneveld prize for doing work that was most beneficial for Holland that year. [1]

Conclusion

The examples described appear to be site specific, and most of us agree that small steps are useless, like a band-aid on a severely wounded body—however, they only appear like that at first glance. In fact, they are implying solutions, structural models for general approaches to allow humans and other species to cope with the change.

The aim of ecological art and related communication should be to make clear that all steps—regardless of their scope—must point in the right direction: That everything— remember Humboldt—is systems-related, so that only systems approaches have a chance to bring about real change. The aim is to incite the necessary changes in human consciousness and action to force administration and politicians to dare real change and take measures affecting systems globally.

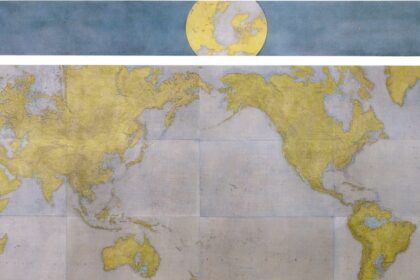

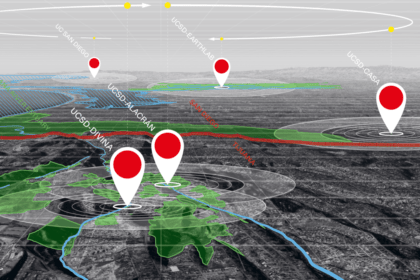

One communication medium that comes close to fulfill all criteria in an almost ideal way with systems in mind and the global ecosystem in view is under development right now by the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure: Sensorium: The voice of the World Ocean, a work of art and science, an immersive, interactive space, an experience, a classroom, and a whole systems solution tool addressing virtually everyone: students, general audiences, scientists and decision makers alike. It invites the participants to “walk the World Ocean,” ask it questions, listen to its response, hear its challenges and discover new insights for ocean recovery solutions to the stresses placed on it. It is designed to cultivate collective-collaborative problem-solving visualizing oceanic issues in such a way that information groups and clusters all at once, inviting holistic perception and synthesis type problem-solving. [2]

Petra Kruse Since 1984 work as art historian (PhD) and editor for various publishing houses and museums, among others, as deputy director of the German Bundeskunsthalle (Federal Hall of Fine Arts); responsible management of numerous international projects; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design and production of exhibitions and books for public and private institutions worldwide together with Kai Reschke. Close collaboration with the Harrisons since 1995, member of the Board of Directors of the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, Co-Director of the European Center for the Force Majeure.

Kai Reschke Since 1982 work as curator, consultant, designer and organizer of exhibitions on numerous large-scale projects worldwide, many of them emphasizing on arts and ecology (e.g. National Park Center); since 1993 lecturing on book and exhibition design, planning, production, technology, didactics and evaluation in collaboration with various national and international government agencies and universities; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design and production of exhibitions and books together with Petra Kruse. Close collaboration with the Harrisons since 1998, Co-Director of the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure and Director of the European Center for the Force Majeure.

Notes

[1] For the Harrisons’ projects see: Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, The Time of the Force Majeure. After 45 years Counterforce is on the Horizon, edited and designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2016), https://drive.google.com/file/d/11a-Cx3RE847NsH_8cCEwwQCtmk_4fQa6/view?usp=sharing

[2] Sensorium: The Voice of the World Ocean. A Vision–A New Kind of Art–A New Kind of Science, edited and designed by Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke (Santa Cruz, CA: The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, 2022), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5238ca6ae4b0cea224f9def4/t/6355b2e01c6c1d267bf8dd6b/1666560737710/SensoriumBookletE.pdf. To learn more about the Sensorium project, see: https://allosphere.ucsb.edu/research/sensorium/ To understand the idea of the Sensorium concept as performed by Newton Harrison watch the video: https://youtu.be/3VFFpt9JshQ Information on The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure may be found under https://www.centerforforcemajeure.org