Searching for Ghosts of the Gulf

Brandon Ballengée, Ph.D. [1]

Let me begin by talking about place and where we all are right now. I am speaking to you from a special part of the world: south Louisiana. This place is special for many reasons, one of which is our rich mix of cultures, including Native American, Creole, and Cajun. We are a slow cooked gumbo of peoples and traditions. Much of the land itself is a former delta and remarkably rich, and this is reflected in our immense terrestrial biodiversity. The living deltas and the water here is special with remarkable freshwater, brackish and the resilient marine biodiversity of the Gulf of Mexico, which in many ways is our North American Amazon Rainforest.

The Gulf of Mexico is a highly productive environment and nursery for thousands. It’s also the home to thousands of shrimpers, and other fisher folk that rely on this not only as a source of income for commercial fishing, but also as a vital source of food, including indigenous populations that still live in these wetlands in villages that you can only get to by boat.

We are also a place of extraction. We are among the top fossil fuel producing states in the United States with immense reserves of crude and natural gas. We supply the US with nearly one third of its seafood and have the largest commercial fishery in the nation. Roughly 3 billion Gulf Menhaden are extracted from Louisiana waters annually which, are ground up and used for animal feed, fish oil pills, and fertilizers.

With all this extraction comes a cost. For example, the 2010 Deepwater Horizon is the largest oil spill in human history. It lasted for almost four months and contaminated the Gulf with an estimation of over 200 million gallons of crude oil. It is estimated that almost half this oil remains in the Gulf, continuing to impact deep water habitats and species. Months after the spill, there is evidence the oil has worked its way into protected areas in the Florida Panhandle. Following the Gulf stream, the oil wrapped its way around Florida and entered the Atlantic coast. Even more than a decade later we are still trying to understand the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon on Gulf communities, species, and ecosystems.

In addition to the oil itself, a decision was made to use chemical dispersants during the spill. These dispersants molecularly break up the oil and make in heavier, so it sinks. In the case of Deepwater Horizon this meant that much of the oil sank and became nearly—if not impossible—to clean. Additionally, laboratory studies have shown these dispersants mixed with oil can be more than 50% more toxic than the crude itself and slow natural decomposing. An important question is how this mixing and sinking impacts deep water habitats, species, and food webs. We still do not know.

There have been over 2000 smaller spills in Louisiana waters since Deepwater Horizon, including the longest running spill in US history. The Taylor Energy or MC20 spill started in 2004 and is ongoing, currently with an estimated release of around 400 to 5000 gallons per day. It’s just off the coast of Plaquemines Parish, south of New Orleans at the base of the Mississippi delta. There has been and continues to be no effort to date to try to stop it by the Taylor company despite a series of litigations. The Taylor family is one of the largest educational and cultural philanthropists in our state and most people here do not even realize the spill is happening.

Going back to the idea of place for a moment, imagine the Gulf and the Mississippi River. The Mississippi has been changing course for thousands of years, moving over time depositing sediment, building land, nurturing species with nutrients, and building habitats. Under all of this are immense reserves of former life, distilled down into petrochemicals such as coal, natural gas, and crude oil. Gulf organisms have evolved to live with the presence of these chemicals naturally in their environment. There are bacteria and microorganisms that help break them down, fish that have adapted to metabolize hydrocarbons, and so forth. The problem with this is that when you have huge volumes of oil going into one place for such a long period of time and spreading, it has a catastrophic environmental impact.

As an artist and biologist, much of my work has dealt with the impact of these spills. As a biologist, my Ph.D. work focused on the growth and development and often deformities found in amphibian populations in agricultural landscapes. As a wildlife rescue volunteer during Deepwater Horizon, I saw firsthand the impacts that spills like that can have. In 2016, I moved to Louisiana and began Post-Doctoral Research into the potential impact Deepwater Horizon had on endemic Gulf of Mexico fishes.

Collapse

As an artist, one of my first artworks that responded to the Deepwater Horizon spill was the installation Collapse. I collaborated with biologists Todd Gardner, Jack Rudloe, and Peter Warny to speculate on potential outcomes of the 2010 spill and express our concerns. While informed by science, Collapse was an artistic response to both my experience on-site during and after the spill, the dead wildlife, and the immediate damage to ecosystems. It was not meant to be didactic in the sense of a natural history museum display. Instead, it was intended to be an expression of and memorial to the lost life of Deepwater Horizon.

Collapse was made 26,162 preserved Gulf fishes and other species in jars, which were stacked one upon the other to form a pyramid sculpture. The shape recalled a food chain and the ecological connection from one organism to another. Empty jars suggested declining species as a result of the spill, or species gone missing post-spill. Such missing species are symptomatic of ecosystems at the brink of collapse. Many of the specimens in the installation were found in 2010 during spill clean-up efforts; others like deformed oil-stained shrimp came from Gulf shrimpers that were concerned with what they found in their catches. Every individual jar was curated and set in relation to other species around it.

Although Collapse is monumental in scale, it is literally a tiny sculptural sketch about diversity of life and the complexity of the Gulf of Mexico food web. In total, there are over 450 species represented in Collapse. Imagine if there were 97 more Collapse installations, that would give us a better idea of what we know lives in the Gulf of Mexico. The work was originally exhibited in New York City in 2012 and has been traveling since.

While at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York City, Collapse received considerable media attention which led to renewed interest in the impacts of Deepwater Horizon. So much so that the then Florida Senator Bill Nelson came to see the exhibition and meet us. Several collaborators and I prepared a dossier exceeding 250 pages about the Deepwater Horizon spill research and its impacts for the Senator. Nelson later went on to become one of the primary politicians involved in the liability case against British Petroleum (BP). This legal action became the largest environmental lawsuit in history with BP being found guilty of over a dozen criminal charges and fined over 5 billion US dollars.

After more than a decade, Collapse was exhibited in 2021 at the Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette, Louisiana. The public response was remarkable, and several Deepwater Horizon platform survivors visited the exhibition and told their stories, as did many other oil and gas workers, fisherfolk, and thousands of others. Collapse finally came home.

In 2016 my family and I moved to south Louisiana from New York City. We made the decision to be at the frontline for climate impacts, work with communities here to try to become more sustainable, adapt to the changes and retreat when we need to. Also, on a personal level, my heritage is mixed and includes Creole and Cherokee, so I felt a kinship to the people of south Louisiana. French is a living language here and people retain much of their historic traditions. We are a Franco-American family and felt a desire to help conserve the special heritage of the peoples here.

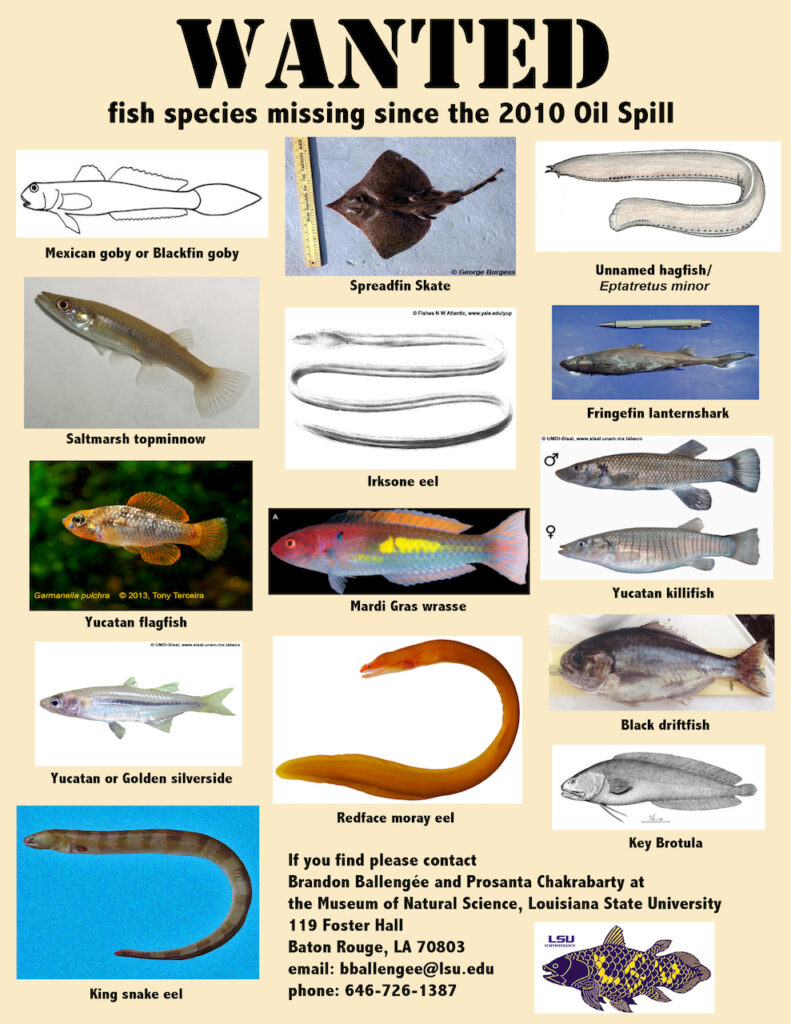

As a scientist in 2016, I began research into Gulf of Mexico fish and potential oil spill impacts on them through a postdoc at Louisiana State University. At any given moment there are as many as 1,500 different fish species in the Gulf, 78 of which are endemic and are not found anywhere else in the world. As part of a team at the LSU’s Museum of Natural Science, we have examined natural history records of the endemic Gulf fishes five years before Deepwater Horizon and five years after. We found that fourteen species were “missing” from the records and had not been reported after the spill. Additionally, several other Gulf endemics have been “missing” for decades. [2] This research was the foundation for the current project, Searching for Ghosts of the Gulf. Significantly for this project is the idea of “searching,” which consists of three primary components: activating, portraying, and exhibiting.

Activating

Coastal Louisiana’s economy strongly relies on its fisheries and the oil industry, both of which have become increasingly unstable in recent decades. Rising seas, coastal erosion, sediment diversions and multiple oil spills have depleted fish populations and have devastated oyster farming. What is happening to Louisiana coastal ecosystems is happening to all of us because we are all intertwined, and I believe art is a great tool to show this.

My form of activism seeks to activate coastal communities through artistic and environmental inquiries into problems facing our coast, coastal habitats, and species. I do this through what I call Eco-Actions, which are open to the public. Here, I invite oil and gas workers, fisher folks, youth and other residents to join me in conducting ecological field sampling looking for missing species. As many of these communities are endangered, searching for missing species is a way to talk about change and loss. I also encourage participants to make their own art to express their concerns, loss, and to try envisioning future scenarios where their communities will adapt and survive.

The Eco-Actions involves citizen science or what I call “participatory biology” where we are literally collecting data and looking for missing species. In addition, these events are an important way for me to learn from residents that are connected about these marsh environments and the fisheries themselves. It is also a means to rebuild trust between coastal residents and scientists, as much of this was lost during Deepwater Horizon. During programs, we discuss the complexity of the Gulf food web, species and habitat disappearances, and create situations where we can strategize a means to help local fisheries become sustainable. By examining complicated socio-ecological issues grounded in scientific facts through the lens of art, we are trying to come up with solutions and begin to take creative actions towards positive change.

A lot of the “activating” has been happening in rural public schools, to which I bring preserved Gulf specimens in jars and other natural history objects. Most of these youths do not have the opportunity to visit natural history museums or art museums as they are far from large cities and transportation is often limited. Likewise, resources are limited in most of these schools. Furthermore, none of the schools I have worked with are teaching students about changes to climate. This is ironic as coastal Louisiana is losing land at the most rapid rate on the planet and is threatened by increased storm strength because of warming. For the most part, these communities lack the economic means that enables mobility to leave if they wanted to. Being aware of environmental change and learning to adapt is paramount towards the survival of many at-risk communities.

One strategy for introducing concepts of adaptation is the “fish drawing workshops”. Here I introduce participants to fish as masters of adaption. Fishes are by far the most successful group of vertebrates—animals with backbones—to ever occupy Earth. Fish are marvels of adaptation and resilience, occupying almost all bodies of water on our planet, and there are nearly 35,000 described species with new species being found all the time. Evidence has shown some fishes can adapt to numerous environmental stressors, including metabolizing hydrocarbons from petrochemicals, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dioxins from other industrial pollutants. Recent studies have provided evidence that several species have adapted to survive and even reproduce in the oxygen depleted “dead zone” of the Gulf of Mexico. Others have adapted to over-fishing by becoming smaller and breeding at a younger age. Still others have been found to be adapting to warming waters by changing their foraging strategies and habitat preferences. Participants in the workshops are encouraged to look and sketch fish specimens while we discuss their evolutionary adaptations. The fundamental questions posed by the workshops is what we can learn from fishes about changes to our communities and environment and how might we adapt to these.

These workshops have been given in schools, community centers, festivals and more recently at the Tulane University’s Suttkus Fish Collection—the largest preserved fish collection on the planet with more than 9 million individual specimens. The collection is housed in World War II ammunition bunkers in Belle Chasse (south of New Orleans in Plaquemines Parish) in a bottom land hardwood forest that is sinking to become a wetland. In one of the bunkers, I have created an impromptu classroom, lab, and studio for creating my own art.

Portraying

Even prior to the Deepwater Horizon spill, several Gulf fishes remained elusive and had not been found in decades (1950 through 2005). Little is known about these species and the only records we have of their existence is a handful of preserved specimens scattered among natural history collections. As an artist and biologist, I am inspired to portray and to tirelessly search for these ghosts.

In response, I create portraits of these missing species, which I refer to as Ghosts of the Gulf, as a way to give form to each of the lost species. The Ghosts are drawn from historic specimens in the Suttkus Fish Collection and others I have photographed and radiographed as a 2017 Artist-in-Residence at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC, USA (the second largest fish collection in the world). Some portraits are printed radiographs or x-rays that have been made into flags that resemble pirate flags. These have sailed at Blessing of the Fleet, ceremonies that happen at the beginning of the shrimp and oyster seasons. The Pirate Jean Lafitte is a cultural icon for the coastal Native American populations, as Lafitte aided the tribes by brokering trade deals on their behalf with the French. Other portraits are painted using actual crude oil from Deepwater Horizon or the Taylor spill. These Ghosts intend to convey mystery as well as melancholy, as a means to engage audiences towards introspective contemplation, asking what is lost from our collective treatment of the Gulf. I am also interested in what creating portraits of missing animals means at a point in history where we find ourselves in a mass extinction event, when species are disappearing so fast that we cannot even scientifically record them.

Exhibiting

To share these works and the participant artworks, I began setting up pop-up exhibitions at unconventional venues such as marinas, seafood markets, parks, libraries, festivals, and other places where fisherfolk, oil field workers, and their families gather. My intention is to reach new audiences and to enlist local residents in Eco-Actions and other activities. My hope is that, collectively, we may yet develop novel strategies to adapt and sustain our communities, human and nonhuman alike.

Working with coastal Louisiana communities over the past decade has taught me that art can be an important icebreaker for meeting residents and a means to discuss complex socio-ecological challenges. Art may also act as an olive branch with fisherfolk and oil workers—many of whom remain resistant to the concept of human-caused environmental impact—who are the population faced with the greatest threats to their culture and livelihoods. Through these pop-up exhibitions, I am able to meet and recruit potential project participants, communicate my environmental concerns and learn about their perspectives, while brainstorming creative ideas towards our survival.

Currently, I am working towards bringing the participant artworks outside of the region, to share what is happening in coastal Louisiana to larger audiences. Our Louisiana communities are remarkably resilient, but they’re tired, lack resources, and we need help adapting. Combined, art and science are complementary ways of trying to understand our world and ourselves, as well as a means to express and pragmatically address the complex socio-ecological challenges we and other species are facing. Perhaps with good fortune we may find some of the Gulf’s lost children and save our home.

Atelier de la Nature

Lastly, I want to discuss Atelier de la Nature. In 2017, my wife, children, and I purchased heavily farmed land in rural Louisiana. On the Atelier land, we have worked to regenerate the ecosystems from soy fields into a nature reserve and eco-campus. By rebuilding topsoil and sculpting the lands with specialized native species that helped to break-down pesticide residue and deter erosion, we were able to plant over 1300 regionally native trees. In doing so, we were able to regrow a forest, create wetland habitats for declining amphibians and rare native fishes, create pollinator habitats from native hibiscus, swamp milkweed, and many more regional plants to aid declining butterflies, like the endangered Monarch, native bees, and others. We have also begun to farm without pesticides using permaculture, Creole, and other indigenous methods.

Atelier de la Nature—meaning “Nature’s workshop” in French—is a communal space, where we offer combined environmental education and sustainable food and art events open to all ages. Our community has a rich historic mix of Cajuns, Creoles, Houma Native American populations as well as more recent Vietnamese and Spanish speaking immigrants. However almost 40 percent of children in our area live below the U.S. poverty rate. As such, our programming is without charge and has multilingual offerings including Cajun French, Kouri–Vini (an endangered local dialect of Louisiana Creole), French, Spanish, English, and we are starting new pilot programs to include Atakapa-Ishak (a local Native American language). We have also started an artist, naturalist, and educator residency program.

The Atelier de la Nature project has already yielded results in the ecological sense with many dozens of species of birds and mammals returning and breeding. Twenty-three species of amphibians and reptiles and countless insects currently occupy the property. During our residency, all of these creatures returned to what not long ago was monocultural farmland. Life will persist if we let it. Life will thrive if we give it a means to do so.

In the human communal sense, hundreds of youths and local residents have helped with the restoration of the twenty-five acres of land or have participated in our programs. We are also partnering with local businesses towards more sustainable practices regionally and throughout the state. We have begun inviting artists to realize ephemeral sculpture made from natural materials that biodegrade, and other forms of ecological artworks.

At the Atelier, Newton Harrison and I along with Lafayette and her students, a flock of sheep, and scientific collaborator Dr. Anna Paltseva—a Soil Scientist at the University of Louisiana—have started a living artwork called Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie. Here we have planted 2.5 acres with native Louisiana prairie, a mixture of plant species called “Cajun Prairie”. This type of prairie is found nowhere else in the world. Historically our area was the southeasternmost portion of the great prairies and was home to Bison, Elk, Red Wolves and other now extirpated species. In the 1800s, Louisiana had an estimated 2.5 million acres of prairie with an estimated 600-700 species of plants and animals. Today less than 150 acres of Cajun Prairie remains and is considered an endangered habitat.

Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie is a living artwork that poses three questions. Is Cajun Prairie an effective means of sequestering carbon? As recent studies have shown prairie grasses work better than trees to sequester and store carbon in the soil. How do different types of disturbances effect biodiversity? There is a body of evidence that grazing and annual burning may change species interaction and diversity. Through this kind of collaborative art and science project, can we increase awareness? Can we inspire larger scale Cajun Prairie habitat restoration? The Endangered Meadows of Europe project by the Harrison Studio in 1994 raised awareness about the threatened habitats of Northern Germany and greater Western Europe. We hope to do something similar in this project.

Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie came about through discussions between Newton and I, and our desire to work together on something at the Atelier de la Nature. Between 2017 and 2021, the soil for Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie began to be worked by rebuilding topsoil and removal of nonnative species. In February 2022, we seeded over a dozen native prairie plants and took soil samples to record pre-prairie carbon levels. Over the next nine years, the plots of Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie will be experimented with by reseeding, carrying out various disturbances to monitor species diversity, and recording the effectivity of carbon sequestering.

If our project works, we will develop an optimal means for restoring an endangered habitat, while creating a novel regional tool for fighting climate change in the heart of an oil and gas state.

Merci pour votre temps.

Dr. Brandon Ballengée (American, born 1974) is a visual artist, biologist and environmental educator based in Arnaudville, Louisiana. Ballengée creates multi-media artworks inspired from his ecological field and laboratory research. In 2013, the first career survey of his work debuted at the Château de Charamarande (Essonne, France), which travelled to the Museum Het Domein (Sittard, Netherlands) in 2014. In 2016, a mid-career retrospective of his work opened at the University of Wyoming Art Museum (Laramie, Wyoming). He has created variations of his trans-species public art series, Love Motel for Insects in nine countries and delivered a TEDxLSU talk about this work in 2020. He has received numerous awards and fellowships, including a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (2017), Awards from the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative (2015, 2016), Creative Capital Award (2019), a Guggenheim Fellowship (2021/22) and was included in the 2020 Grist 50 Emerging Environmental Leaders. He holds a Ph.D. in Transdisciplinary Art and Biology from the University of Plymouth (England). Currently, he is an Adjunct Faculty of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Tulane University studying the impact of the 2010 oil spill on Gulf of Mexico fish species. In 2016, Ballengée in partnership with his wife—sustainable food educator Aurore Ballengée—began the Atelier de la Nature: an eco-educational campus and nature reserve in Arnaudville, Louisiana.

Brandon would like to acknowledge and give thanks for the support of his “Searching for Ghosts of the Gulf” to: A Studio in the Woods in partnership with Plaquemines Parish Government supported by an Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts; COAL Coalition pour l’art et le development durable; The John Simon Guggenheim Foundation; Creative Capital; Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History; Tulane University Biodiversity Research Institute (TUBRI).

Notes

[1] Transcribed and adapted from “Searching for Ghosts of the Gulf” a presentation given at the Listening to the Web of Life Workshop on March 17, 2022.

[2] Prosanta Chakrabarty, Glynn A. O’Neill, Brannon Hardy, and Brandon Ballengee, “Five Years Later: An Update on the Status of Collections of Endemic Gulf of Mexico Fishes Put at Risk by the 2010 Oil Spill,” National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information (August 18, 2016), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5018106/