Metapoiesis: Art that Yields to Life

David Haley

1. Preamble

shifting the baseline

shifting markers and goal posts

shifting with the sands

Writing this text gave me the opportunity to assemble ideas that I have been working on for over thirty years, some of which were initiated by Helen and Newton, some by others and some that emerged from questions that continue to ferment within me. My primary focus is the potential for life beyond the nexus of climate, species and cultural crises.

The two main projects I worked on and learned from Helen and Newton were Casting the Green Net (1996-98) [1] and Greenhouse Britain (2005-10) [2]. Each had important subtitles that expanded the key project metaphors.

Casting A Green Net: Can It Be We Are Seeing a Dragon

This project emerged from the idea of a mythical giant, standing astride the Mersey Estuary. He casts a magical net across northern England and where it touches earth, biodiversity connects ecologically, rhyming the Mersey and Humber estuaries. One morning, working on the floor, twelve art students at Manchester Metropolitan University were redrawing a large-scale OS map to depict the net’s landfall. Newton walked into the studio, saw their work and declared; “My god, can it be we are seeing a dragon?” The story of the net and the dragon created an imaginative space to advance rigorous, new, commercial and ecological paradigms that, twenty years later, have become a UK Government initiative, The Northern Forest [3]. The Harrisons’ work advanced the concepts of:

- Potential interconnectivity of an ecologically defined region

- The regional scale of an ecosystem, comprised of watersheds and sub-systems

- Encompassing, strategically planned, urban development as an economically viable means of promoting biodiversity and valuing culture

- Incorporating bio-waste into regional urban/farm-scapes to reduce expensive inorganic fertilizer usage and produce organic food for an increasing population

- Placing such a region in the context of international trade and politics

- Considering unfettered urban sprawl as a market-driven alternative

Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom

In 2005, at the end of the Evolving the Future international conference, my invitation to see mainland Britain as one ecological, geophysical entity, stressed by global warming, advanced the Harrisons’ existing greenhouse metaphor (The Mountain in the Greenhouse) [4]. By adding “Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom”, they shifted the UK Government’s scientific approach to sea level rise of “managed retreat” to “withdraw with grace”, or “Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom”; thereby the engineered military metaphor shifted to yielding and learning. Again, making a new space in which we may adapt to the world becoming and “turning the face of disaster to the face of opportunity” [5].

2. Bluebells

where once was forest

awaiting within the soil

time for sheep to leave

This story begins in June 2021. Walking with friends from Chrysalis Arts Development [6] and two farmers in Malhamdale, North Yorkshire, the farmers explained their experimental strategy to promote wildflowers for pollinators, by laying a field fallow from sheep grazing for a year. Unexpectedly, beside a small beck (stream) that cut across the field, bluebells grew the following Spring. I noted that bluebells were naturally a forest flower and the farmers agreed. But there were no trees nearby and very few across the whole landscape. For generations, the baron moors of Bronte’s Yorkshire have been overgrazed by cattle and sheep. Local tourism, traditional farmers and gamekeepers claim that no forests ever existed there. While laying a field fallow is a well-established agricultural form of yielding to permit soil recovery, this event generated a space for regeneration and inquiry.

The mysterious bluebells not only pointed to the potential that lay in the ground for hundreds of years, but the possibility that these flowers were native English bluebells.

3. Decolonial Discourse

where the power lies

redirect our energies

emancipation

Between the 17th and 18th Centuries, the Age of Enlightenment saw European nations fight to consolidate their colonization of much of the world, through reason. Rene Descartes’ application of mathematics and philosophy designed the cartesian grid. As profound as Apollo 17’s 1972 photograph of Earth from space, but from a different perspective; the later image came to represent our relationship to a vulnerable planet within a vast cosmos, while the former contained the globe as one space to be objectified and exploited. From Francis Bacon (1561-1626) to Denis Diderot (1713-1784), David Hume (1711-1776) and Adam Smith (1723-1790), the Enlightenment also established the first world political, empirical, economic system based on energy – labor from human resources, otherwise known as slavery. At the height of the Industrial Revolution, the abolition of slavery culminated in 1865 with the USA’s 13th Amendment and within five years, global economics shifted to the world’s first incorporation – Standard Oil [7]. Through the 20th Century to today, colonial power and thinking are perpetuated through myths of evolutionary survival of the fittest and latterly played out through the neoliberal oxymoron of “Sustainable Development” [8].

Recently in the West, despite COVID-19, some events have acted as catalysts for potential systemic social challenge (i.e. Me Too [9] Extinction Rebellion [10] Black Lives Matters [11]), but so far these campaigns remain fragmented, prompting at best tokenistic responses from the establishment within education, industry, commerce and mainstream politics [12]. In other words, the causes become marginalized and as such have no space for expression. Angry voices continue to be ignored, smothered or distracted by what the Romans called “bread and circuses”.

Decolonizing Divisive Digital Devices

Throughout education at every level, data becomes global cognitive dissonance, when dependent on disciplinary domains [13], crowding out space for thought. Information replaces knowledge and understanding is erased by monoculture, leaving us to romanticize and appropriate remaining indigenous cultures.

While the idea of decolonizing starts with emancipation from the intersection of racism and misogyny [14], other intersectional narratives unravel; through education to climate, environmental sciences, the arts and above all, the media for cultural erasure.

My personal concern is to bring “critical eco-pedagogy” to eco-cultural disengagement – how homo sapiens became homo urbis and then homo digital. I am deeply concerned by this cognitive disconnect, reliance on industrialized urban infrastructures and dependence on digital devices that degrade our life support systems and consume culture, to render the human species disastrously vulnerable. In a recent article for the Guardian, Rebecca Solnit wrote:

Computer technology, specifically the technology Silicon Valley has brought us, would amaze and horrify our forebears. Stalin’s secret police, the US’s FBI and East Germany’s Stasi never imagined the capacities to violate our privacy and document our every expenditure, action and affiliation that Silicon Valley has provided, along with stalkerware, facial recognition technology and other forms of surveillance. They have made China a place in which state control relentlessly reaches into the smallest corners of everyday life. There, this intrusion is not optional; in the west, people cheerfully buy expensive tracking devices that also serve as phones and hand their data to every website they visit. You can opt out, but people blithely, blindly opt in [15].

4. The Scientific Method

an education

to make our children like us

systems of control

or

a pedagogy

let our children be themselves

free from oppression

Colonialism was never just about territory, resources extraction and the economics of slavery [16]. As strange allies, mathematics, natural philosophy, Renaissance politics and religion gave birth to the shift in thinking we call science. More precisely, the politicized scientific method was developed to control how we perceive everything in the world and what we believe to be true. This pervasive cognitive insistence of the right way to think and do, despite theories of complexity, chaos and ecology, is embedded in every level of education, through most institutions in the West, East, North and South. Universalizing the correct way to think and damning others has evolved into the binary aspects of the wicked problems and double-binds we live with [17]; our mental space is therefore compromised.

5. Yield to Change

giving way to change

giving way to potential

learning how to yield

In their book, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, Gunderson and Holling differentiate between “engineered resilience” and “ecological resilience”. While engineered resilience is concerned with duration – how long a system can carry on – ecological resilience considers the inevitability of all systems to collapse and the next state of becoming to be part of the adaptive cycle, as one system flips to another [18].

I consider this realization to be the art of yielding that I first understood from Eduardo Paolozzi’s exhibition catalogue, Lost Magic Kingdoms and Six Paper Moons from Nahuatl, at the Museum of Mankind, when he wrote: “What we need is a new culture in which way, problems give way to capabilities” [19]. I have always challenged the oxymoron of Sustainable Development, preferring sustainable living or “capable futures” [ 20], wherein our most pressing problems give way, or yield to potential gain.

I physically experienced such yielding while practicing different aspects of Tai Chi and Qigung in which the processes of change are employed and deployed – to heal and defend, recoil and counter, by receiving and owning the energy from attack or stress and returning it. Such practices may enable us to identify, own and resolve our vulnerabilities.

To yield is not to retreat, give in or be defeated. To yield is to give way to profit, perhaps with grace and thereby become. Such yielded space creates a vacuum for life to inhabit – a space for change to metabolize. But none of these forms of yielding come “naturally”, as they are counter-intuitive, they must be learned through culture [21].

6. Learning Culture

learning how to fly

in this never-before world

learning to be wild

Chiming with my observations of parent seagulls teaching their chicks how to fly, an article in the Guardian newspaper, reported on “fundamental culture” in animal behavior [22]. The article focused on the work of the Macaw Recovery Network in Costa Rica, re-wilding captivity-hatched fledgling scarlet and great green macaws. Bereft of the cultural education, normally provided by parents, the birds were unable to cope with the complex forest world into which they were released. The had not learned how to find food, identify danger nor find mating partners, so most died within a few days. Crucially, researchers noted that culturally learned skills vary from place to place, so when habitat is lost, it’s not just the physical populations that decline, it’s their culture and this cannot be replaced by physical restoration alone.

The article posed the question, “How can we survive here, in this never-before world?” [23] and I believe similar narratives apply to humans when I emphasize the nexus of crises we face as climate, species and culture. Survival of numerous species depends on intergenerational cultural adaptation, contained in the dialect of local languages, migration patterns, nesting sites and breeding grounds, food sourcing, tool making, birdsong, the calls of cod, the social organization of orca whales and communities of chimpanzees. The culture of free-living animals is only visible when its disrupted. Reestablishing cultures – how we live in this place – is difficult and often fatal.

7. Counting on Culture

The biggest challenge facing humanity, therefore, is how to educate ourselves for future generations to learn how to meet the realities of climate, species and cultural crises. All disciplines and curricula must focus on this nexus of transformative challenges if education is to have any relevance beyond the absurd silos of academia.

In 2021, during the COVID -19 lockdown, I and my friend and colleague, Valeria Vargas, Research Associate in Education for Sustainable Development in the Department of Natural Sciences at Manchester Metropolitan University, completed two small research projects. The first, Counting on Culture: Taking Stock of Change, critiqued and contributed to the form of the National Census, by exploring non-statistical data knowledge, through unscientific methods of understanding the profile and aspirations of diverse community cultures. We, effectively, created a space to think differently.

Every ten years, the National Census, in the UK, gains data primarily based on places of dwelling and material factors, to be used by central and local governments, market research and research agencies. 2021 was the first time it included questions about people’s ethnicity and sexual orientation, but it still missed the complexity of people’s community distinctions, cultural connections, personal narratives and future prospects – many of the things that people actually identify with, believe in and care about.

To commence, we adopted a random, organic method of selecting interviewees, starting with someone who knew someone on Stretford Road, Manchester – a street near the university. They, in-turn, passed us onto someone they happened to know and so on. As it happens the first person we interviewed worked at Z-arts [24], a family focused community arts organization based near the university, with culturally diverse, intergenerational attendees – and from the first interviewee we gained links to people from Hong Kong, Kenya, Scotland, Essex, Pakistan and so on.

The project included an online exhibition of interviewees’ chosen objects of personal significance and to upturn the power relationship of such research [25]. We asked the children of Z-arts, who had participated in our complementary creative survey workshops, to curate the exhibition. The children went on to record the voice-overs of anonymized responses from our adult interviewees, contributing an added nuance.

This project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), through the United Kingdom Research Council (UKRC) and was praised by them, at a debriefing session for its unusual approach to research.

8. Generous Domains

The second project was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) through the United Kingdom Research Council (UKRC). Entitled Generous Domains: Global Citizenship Perspectives for Environmental Sciences, it explored the UKRC’s Hidden Histories call to consider:

To what extent has colonial and other history, exclusion and social injustice influenced how the UK environmental science research sector presents cultures and issues, including around race, racism and representation and intersectionality?

While both projects explored practical applications of futures-facing, heuristic ontological approaches, derived from creative eco-pedagogical research (otherwise known as “storying” [26], or the making and telling of stories), Generous Domains was met with incredulity and derision by the university’s Faculty of Science and Engineering Research Department. However, this project was initiated by a conversation I had in a meeting of the Future’s Venture Foundation [27], when I expressed my disappointment that within its seven-year life, none of the artists we had funded had focused on climate and biodiversity. This was met with the words, “That’s white man’s science”, from one of the artists and I wanted to learn more about what this challenge meant.

Our project partners, again included:

- Z-arts

- The People’s Republic of Stokes Croft, an environmental activist arts and crafts organization based in a poor white area of Bristol [28]

- CARGO Movement, a creative black youth collective, based in St Paul’s Bristol, with an international following [29]

- The Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management, that has an international membership and is closely aligned with UK Government agencies, industry and commerce [30]

- The UK Urban Ecology Forum, a think-tank of academics and representatives across the sciences, arts and environmental sector [31]

- The National Wildflower Centre, based in Liverpool and now part of the Eden Project [32]

Other individuals represented Black arts, psychosociology and environmental ecology.

The first online meeting with our project partners was a failure, in that only Valeria and I attended. However, from our initial conversations with the partners, we noticed surprising attitudes that ranged from fear, frustration and guilt to anger, confusion and avoidance, so we decided to interview people individually and then asked them to organize meetings within their respective organizations. The spectrum of responses expanded greatly, from academics puzzled by “… exceptional black PhD students in Environmental Sciences, who just went on to do other things”, to seven young black artists filming their conversation, based on our research questions, who defined their meaning of “environment”. The project concluded with an online meeting of all the people who should have attended the first meeting, and this revealed great emotions and expressions of deeply held vulnerabilities, double-binds and celebration [33], with one participant declaring that we had created “a safer space”, beyond trust.

9. Potential Hope

making potential

questions not answers to learn

storying as life

Returning to the bluebells, the point is that within the process of destruction there may be the potential space for creation – like Shiva Nataraja dancing Tandava, creation and destruction form an inseparable rhythm.

In 1999, having read about Maturana and Varela’s Santiago Theory of autopoiesis [34], I presented the idea that ecological arts might offer a form of “ecopoiesis” [35].

Google didn’t exist then, so I was unaware that in 1990, Robert Haynes, working on NASA’s Terraforming program to colonize Mars, coined the word, “ecopoiesis” [36] to describe the creation of ecosystems in extreme environments, on other planets. In 2009 I retained my interpretation within the context of ecological arts to describe the re-creation of ecosystems from extreme environments, on Earth [37].

Later another friend, Sacha Kagan, developed the notion of “auto-ecopoiesis”, to consider the ability of ecosystems to recreate themselves, thereby extending the principle of potential [38].

Aside from academic ways of wording our world, the ideas are important in that the discourse, from ecological conservation to restoration to management, had moved on to considering the real possibility for eco-systemic collapse and the potential for regeneration [39] [40]. All systems eventually collapse, but they have the potential to flip into another state of being [41].

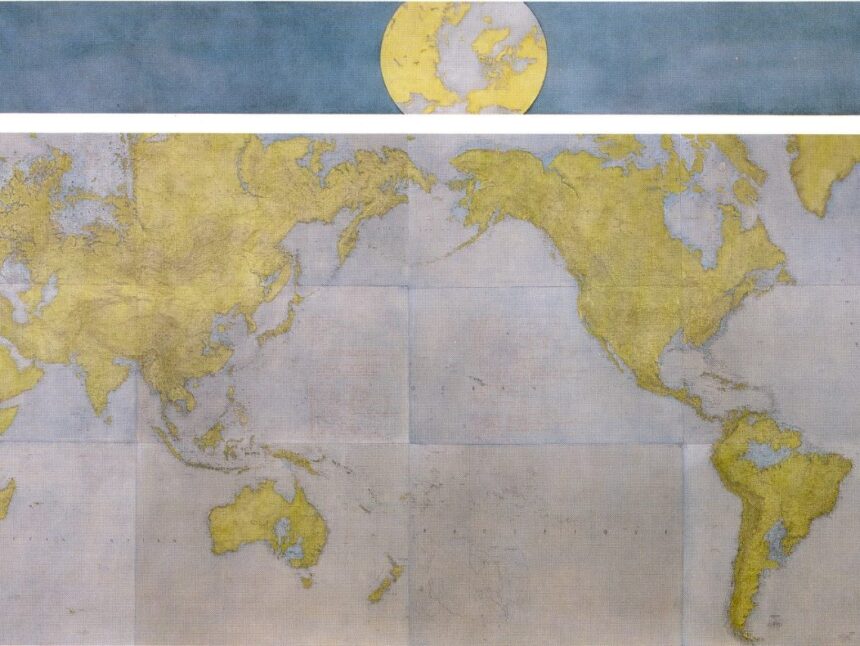

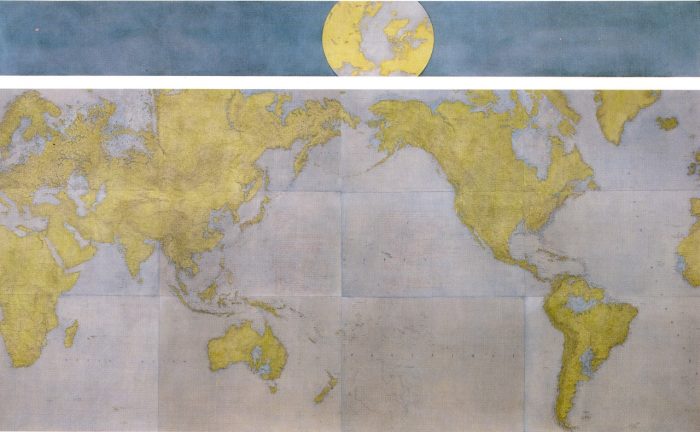

Here it is worth reflecting back to the images of Descartes’ globe and Apollo 17’s “Blue Marble” to the Harrisons’ Lagoon Cycle (1974-1976) [42] worldwide view of sea level rise, a future projection of transition to another space.

10. Metapoiesis

throw rock into pond

splash. rock sinks. ripples disperse

still water remains

When Robert Pirsig wrote: “The most moral act of all is the creation of space for life to move onwards” [43], as well as physical space made by creating habitat, “space” includes the personally cognitive and socially cultural spaces. This is the metanarrative; the heuristic ontological structure, pattern and process to think regeneratively [44] [45].

In decolonial discourse, it is the “safe space” beyond trust. In dialogical pedagogy, it is the space made by a question from which we may all learn for ourselves. In knowledge, it is experiential knowledge and the potential emergence of Transdisciplinary Knowledge [46] [47]. And in ecology, “it is the pattern that connects” in time [48].

So, when it comes to “the nexus of climate, species and cultural crises”, we may have the potential capacity to live with and through these transformative challenges. In practical terms, it is creating “critical recovery” to survive ongoing disasters and the need for “integral critical systems” to continually assess the validity of the systems and values we apply to dynamic situations [49]. The nexus of crises may then prompt a regenerative continuum on the adaptive cycle of a world becoming [50]; born out of the chaos of non-equilibrium [51]. In other words, Metapoiesis is a potential contribution to the life web, but certainly not the whole story.

sing before we speak

how being is learning with

dance before we walk

metapoiesis

emergence beyond making

art that yields to life

David Haley PhD HonFCIWEM is an ecological artist, researcher and eco-pedagogue. Haley, publishes, exhibits and works internationally with ecosystems and their inhabitants, using images, poetic texts, walking and sculptural installations to generate dialogues that question climate, species and cultural crises for “capable futures”. Haley is a Visiting Professor at Zhongyuan University of Technology; Guest Professor at Sichuan Fine Art Institute and Universidad Iberoamericana; Vice Chair of the CIWEM Art & Environment Network; Mentor/Advisor (founder) of Futures’ Venture Foundation; a Trustee of Chrysalis Arts Development and Art Gene; a member of the ecoart network, UK Urban Ecology Forum and Ramsar Cultural Network.

Notes

[1] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, “Casting A Green Net: Can It Be We Are Seeing A Dragon”, for Artranspennine98 (Liverpool, Bluecoat Gallery, 1998).

[2] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, “Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom”, (Totnes, CCANW 2008; Shrewsbury, Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery; Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University 2009; New York, Feldman Fine Arts 2010).

[3] The Northern Forest https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/we-plant-trees/the-northern-forest/

[4] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, “The Mountain in the Greenhouse” (2001) https://exhibits.stanford.edu/harrison/catalog/kg813rp8299

[5] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, “Public Culture and Sustainable Practices: Peninsula Europe from an Ecodiversity Perspective, Posing Questions to Complexity Scientists”, in Structure and Dynamics: eJournal of Anthropological and Related Sciences, Volume 2, Issue 3, 2008, Article 3, http://repositories.cdlib.org/imbs/socdyn/sdeas/vol2/iss3/art3 Retrieved 18 November 2016.

[6] Chrysalis Arts Development https://www.chrysalisarts.com/ https://www.chrysalisarts.com/projects/fivehectares

[7] Standard Oil https://www.britannica.com/topic/Standard-Oil

[8] David Haley, “‘Undisciplinarity’ and the Paradox of Education for Sustainable Development”. In ed. Leal Filho, W. Handbook of Sustainable Science and Research Series, Climate Change Management (Springer 2017).

[9] Me Too https://metoomvmt.org/

[10] Extinction Rebellion https://rebellion.global/

[11] Black Lives Matter https://blacklivesmatter.com/

[12] Albert Memmi, The Colonizer and the Colonized (London, Profile Books, 2021).

[13] Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Anti-fragile: Things that Gain from Disorder (London, Penguin Books. 2012)

[14] Vanessa Andreotti, “Global Citizenship Education Otherwise: Pedagogical and Theoretical Insights”. In Ali Abdi, Lynette Shultz, and Tashika Pillay (Eds.) Decolonizing Global Citizenship Education (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2015), pp. 221-230.

[15] Rebecca Solnit, “A Planet in Peril and Our Embrace of Big Brother: George Orwell Would Have Been Shocked,” The Guardian (June 24, 2022) https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jun/24/big-brother-george-orwell-climate-change-surveillance?utm_term=62b5df865b7b4a3706f9b550be4e76a1&utm_campaign=BestOfGuardianOpinionUK&utm_source=esp&utm_medium=Email&CMP=opinionuk.

[16] Kojo Koam, Uncommon Wealth: Britain and the Aftermath of Empire (London, John Murray 2022).

[17] Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, John H. Weakland, “A Note on the Double Bind – 1962” (accessed 29 June 2022) http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/nursing/m4050/baker/8571Su03/Bateson.pdf.

[18] Lance H.Gunderson and C. S. Holling (Eds.) Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington, Island Press, 2002).

[19] Eduardo Paolozzi, Lost Magic Kingdoms and Six Paper Moons from Nahuatl (London: British Museum Publications, 1985), p. 7.

[20] David Haley, “The Limits of Sustainability: The Art of Ecology,” in S. Kagan and V. Kirchberg, eds. Sustainability: A New Frontier for the Arts and Cultures (Frankfurt, Germany: VAS-Verlag, 2008), p. 203.

[21] Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London, Fontana Press, 1988), p. 50 & 213.

[22] Edgar Morin, On Complexity (New Jersey Hampton Press Inc., 2008).

[23] Carl Safina, “The Secret Call of the Wild: How Animals Teach Each Other To Survive” Guardian (April 9, 2020) https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/09/the-secret-call-of-the-wild-how-animals-teach-each-other-to-survive-aoe (Accessed 29 June 2022)

[24] Z-arts https://www.z-arts.org/

[25] Counting on Culture https://www.z-arts.org/the-art-of-storytelling/

[26] Samuel Taylor Coleridge https://www.z-arts.org/the-art-of-storytelling/

[27] Future’s Venture Foundation http://futuresventure.net/

[28] People’s Republic of Stokes Croft https://prsc.org.uk/

[29] CARGO Movement https://cargomovement.org/

[30] The Chartered Institution for Water and Environmental Management https://www.ciwem.org/

[31] UK Urban Ecology Forum https://urbanecologyforum.org.uk/

[32] National Wildflower Centre https://www.edenproject.com/mission/our-projects/national-wildflower-centre

[33] Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, John H. Weakland, “A Note on the Double Bind – 1962” (accessed 29 June 2022) http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/nursing/m4050/baker/8571Su03/Bateson.pdf.

[34] Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varella, The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding (Boston, Shambala Publications Inc., 1998).

[35] David Haley. “March 2001: Reflections on the Future – ‘O brave new world’: A Change in the Weather” in Antoni Remesar ed., Waterfronts of Art I, Art for Social Change, University of Barcelona, CER POLIS, Spain www.ub.es/escult/1.htm and CD ROM pp. 97-112.

[36] Robert H. Haynes, “Ecce Ecopoiesis: Playing God on Mars. in Moral Expertise: Studies in Practical and Professional Ethics, ed. Don MacNiven (New York: Routledge, 1990), pp. 161-3.

[37] David Haley, “Ecology and the Art of Sustainable Living” Field: A Journal of Socially Engaged Art Criticism Vol. 4 Issue 1 (2011) pp. 17-32. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/20827618/2-ecology-and-the-art-of-sustainable-living-field-journal.

[38] Sacha Kagan, “Cultures of Sustainability and the Aesthetics of Pattern that Connects” p.5. (Accessed 29 June 2022) https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/9/9453/files/2010/12/Kagan_cultures_sustainability_5.2.09.pdf

[39] Jared Diamond. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive (London, Penguin, 2006).

[40] Daniel Christian Wahl, Designing Regenerative Cultures (Axminster, Triarchy Press, 2016).

[41] Lance H.Gunderson and C. S. Holling (Eds.) Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington, Island Press, 2002).

[42] Helen Mayer and Newton Harrisons, “The Lagoon Cycle” (1974-1984) https://theharrisonstudio.net/the-lagoon-cycle-1974-1984-2.

[43] Robert Maynard Pirsig, Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals (London: Black Swan, 1993), p. 407.

[44] Fritjof Capra, The Web of Life: A New Synthesis of Mind and Matter (London, Flamingo, 1996).

[45] Daniel Christian Wahl, Designing Regenerative Cultures (Axminster, Triarchy Press, 2016).

[46] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1980).

[47] Basarab Nicolescu, Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity (New York, State University of New York Press, 2002).

[48] Gregory Bateson, Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity (New Jersey: Hampton Press, 2002), p. 7.

[49] David Haley, Alberto Paucar-Caceres and Sandro Schlindwein. “A Critical Inquiry into the Value of Systems Thinking in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis,” Systems 2021, 9(1), p. 13.

[50] Lance H.Gunderson and C. S. Holling (Eds.) Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington, Island Press, 2002).

[51] Eric D. Schneider and Dorian Segan, Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics and Life (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005).