Bonds Between Art and Life: for a Terrestrial Habitability

Nathalie Blanc

A new direction needs to be fostered in our relations to the environment and nature, hence the interest in cross-fertilization between art and ecology. All my research and creative work are so aimed. In 1993, after a short spell in the fine arts, I sought political engagement – not in a partisan manner but in the wider sense of actions directed at transforming our social organization – and I undertook a doctoral thesis on nature in cities. I chose to analyze the role of animals in cities, and more particularly the place of the cockroach. Subsequently, I entered academia and pursued aesthetic commitments aimed at revealing contemporary ecological absurdities, such as the denial of the power of the natural world. I sought to link, on the one hand, intellectual forms of reasoning that are embedded in the real world and, on the other hand, forms of narrative emergence open to the unknown, to creativity and exploration, not to mention to experimentation. Politically, my research strongly contrasts with many of the practices of the 1980s, which were more concerned with formal games and individual existences, unlike the more politically conscious artistic practices of the 1960s and 1970s. It is thus that in 2006, at a time when works confronting ecology and art were rare in France, I organized the first colloquium on environmental aesthetics, linking reflections on art and the philosophy of aesthetics, as an extension of American environmental aesthetics. It was my intention, particularly in the French context, to offer perspectives other than those of science, especially natural science, on the environmental and social crises and, more generally, the civilizational impasse which, at the time, was easy to anticipate for those who, like me, were engaged in political ecology.

What was missing then and is still missing today in the analysis of social, environmental, and political crises? These analyses lacked, and still lack, consideration of the centrality of terrestrial materiality. After the cultural turn in the 1980s, which led social and human sciences to move away from a positivist epistemology and take into account the constitutive and explanatory role of culture in the analysis of social and natural phenomena, since the 1990s, there has been a material turn in the field. This movement led the social and human sciences to focus on the objects, instruments, corporeality, and materiality of socio-material organizations (for example, structures, arrangement and agency, intentionality, process, movements, relationships, networks, entities, substance, technologies, semiosis, etc.). While many academic works overlooked this epistemological shift, certain works did take it into account, particularly in the social sciences and humanities. However, they did not interpret ecological materiality as having its own agency and its own power, which is clearly not to be overlooked but requires a methodological update that allows nature to express its voice. On the other hand, in the art world, most artists at the time were still heir to modernism and entrenched in an ivory tower.

Fortunately, when it comes to debates on the ecological catastrophe, questions about ecological agency and terrestrial habitability have been on the table for a long time, thanks, in particular, to the work of the Harrisons. The 1970s marks the beginning of the Harrisons’ work and the increasing awareness of and emphasis on a finite and fragile planet. The ecological crisis raises questions about the fallibility of human development, and even of human history, as a civilizational epic. Onboard a damaged Earth-ship, the survival of the human species is also at stake, though the population is slowly becoming aware of the risks involved and the inanity of a race that pursues economic growth at the expense of endangering the habitability of all or part of the Earth. These contemporary reflections, which pay attention to the dangers inherent in the modes in which we currently inhabit different terrestrial spaces, invite us to radically reinterpret the concrete and symbolic ways with which we approach the ecological reality. In the following, I will examine diverse artistic works that reinterpret and interrogate the idea of terrestrial habitability, in which the Harrisons’ contribution stands out.

Terrestrial habitability

Environmental art with a habitability awareness has been confused with Land Art in a rather deceptive manner since its origins in the mid-1960s in the United States with artists such as Alan Sonfist, Patricia Johanson, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, or in Europe with the German artist Joseph Beuys. Also emerging in the 1960s, the latter movement brought together American artists working with natural materials, often outside art galleries in deserted places, modeling monumental landscape sculptures. Meanwhile, in the United States in particular, environmentally-oriented artists decided to make nature the medium and object of their works and ideas. Even though their intentions were very different from the get-go, since they also used nature in their works, environmental artists were subsumed to Land Art. This was very problematic, first of all since it perpetuates the common confusion between a landscape spectacular to the eye, a view often taken by painters throughout history, and a nature considered not as a substance or expanse to be developed but as a process, which is studied by natural scientists and advocated by poets. Secondly, if we compare works associated with these two movements, similarities are difficult to find. What do Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) or Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1976), minimalist sculptures that include the surrounding landscape and connect to the natural circadian temporality of the Utah Desert, have in common with Time Landscape (1965-78) by Alan Sonfist, a micro-forest composed of indigenous species in the heart of Manhattan? What links monumental installations incidentally altering the local ecology to a New York Forest reconstructed after an archaeological template to install a green lung in the north of the SoHo district? After all, the former only uses the landscape as a backdrop, while the latter considers the problems of life and survival against the notion of terrestrial habitability.

But how do we define terrestrial habitability and why does it matter? The Earth Politics Centre (Centre des Politiques de la Terre) has worked to characterize this term in an interdisciplinary manner [1], knowing that the current crisis presages catastrophic prospects [2]. The following lines are inspired by their work.

The magnitude of the socio-environmental crisis is clear, attested worldwide by a set of diagnoses concerning the entire planet. Despite glaring government inaction, debates on this crisis are now omnipresent in the public discourse that understands climate change as irreversible. Given the prevalence of the crisis, one must consider not just the sustainability of the development of human societies but the survival capacities of the human species in terms of the habitability of terrestrial environments [3]. The notion of habitability characterizes the possibility for living beings to formulate adaptation strategies in the face of opportunities and constraints, whereas the concept of planetary limits refers to the limit within which certain spaces remain inhabitable and/or to the possibility that certain living spaces will become uninhabitable [4]. The planetary limits which are at risk of being crossed threaten to tip a system hitherto relatively well-regulated towards a degraded state unfit for human life.

Risks of global environmental changes fall in nine critical biophysical regulation systems linked to human activities, which together are supposed to ensure the stability of the planet, that is to say, its “homeostasis.” These are global climate change, erosion of biodiversity, disruption of the biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus, changes in land use, ocean acidification, global freshwater use, stratospheric ozone depletion, increased atmospheric aerosols, and chemical pollution. The changing earth demands the evolution of human societies, as it is now necessary to inhabit the planet differently. It not only questions the capacities of the human population to transform lived environments in situations of increasing constraints but also asks how we can and should transform the relationships that humans have with non‑human life as well as with the environment which was previously considered to be a lifeless decor. Imagining these social and environmental transformations means reframing our ways of inhabiting in a conscious way.

Given the urgency of these ecological challenges, what is the relevance of focusing on cultural issues? In the broadest sense, culture means a set of practices and representations that structure our ways of life in society and ensure its transmission. At this critical moment, it is urgent to reconsider the cultural foundations that govern our representations of the world and that have led us, and still lead us, to ignore the material consequences of our actions and to refuse to recognize that the materiality of the planet constitutes a hard limit constraining human imaginations and developments. These representations are variegated, including maps, photographs, paintings, globes, sign systems, etc. Their prevalence shows how essential it is to consider the cultural dimensions of terrestrial habitability. This is the question asked by artists involved in environmental and/or ecological art since the 1970s. This expansion of the artistic practice to include art engaged with ecology transforms the role of artists in society.

Of ecological artists

From the 1960s onwards, many women artists, including Agnes Denes, Mierle Ukeles, Patricia Johanson, and Lynne Hull, have been interrogating a fundamental dimension of terrestrial habitability, namely the care needed to reproduce the living. For them, concern for the living also entails a concern for the reproduction of environments and their caring. They transformed the essence of ecological artistic projects from “conquest of nature” to “cohabitation with nature.” Their works considering the need to take charge of environments including their possible demise are prefigurations of contemporary concerns.

The famous installation by Hungarian-born Agnès Denes, Wheatfield: a Confrontation (1982), featuring wheat fields in Lower Manhattan, deals with the conflict between eco-art, artistic installation, Land Art, and social change. This installation traveled the world as part of an exhibition entitled “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger,” organized by the Minnesota Museum of Art (1987-90). It consists of a two-acre planting of wheat on a lower Manhattan landfill in 285 furrows yielding 1,000 pounds of wheat. This performance put into tension the pollution of the earth and land at the expense of food security and the misplaced priorities between consumption, waste, and hunger, at a time when these issues were still largely ignored. A time capsule was planted in the ground reflecting the work and its context, intended to be opened in 2076.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who wrote the feminist Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969!, was one of the first artists to highlight the differences between caring for the environment and an essentially technocentric conception of the environment. Her work profoundly conceptualizes the idea of “maintenance” or the day-to-day management of social entities or bodies perpetually inscribed between life, reproduction, and death. Recounting her personal situation, she addresses the fact that because she is, like any person, responsible for her existence, she must take into account the general condition of living beings and of the Earth.

For Patricia Johansson, art is a matter of survival. In 1992, she created an exhibition and a book, Art and Survival: Creative Solutions to Environmental Problems, strongly based on ecological engineering. She uses drawing as the basis of her composition to create interwoven structures of nature and culture. She has drawn hundreds of sketches for environmental projects and developed numerous designs for water gardens (flood pools, dams, reservoirs, and drainage systems), ecological gardens, marine gardens, municipal lakes, and roadside gardens. For instance, in Cyrus Field (1970), a seminal work in her oeuvre, the artist “linked a geometric marble path to a redwood maze configuration to a concrete pattern. Created in the woods near her Buskirk, New York home, the forest’s irregularity disrupted this work. Like Haacke’s Grass Grows (1969) or Sonfist’s Time Landscape (1965/1978-present), Cyrus Field inspired visitors to focus on ecology” [5]. This work stands out for its take on permanence. According to the artist, “The traditional art object is based on the idea of perfection […] Cyrus Field is alive. The piece grows and changes; it is in the process of becoming other things” [6].

For more than 35 years, Lynne Hull’s mixed media work has focused on the ecological realities of the American West and different sites around the world. She specializes in sculpture as a habitat for wildlife, and its principal spectators are hawks, eagles, bats, beavers, spider monkeys, and migratory birds that travel from Canada to Latin America. She has established sanctuaries for birds of prey in Wyoming, hibernation sculptures for butterflies in Montana, salmon ponds in Ireland, and nesting sites for wild ducks and geese in the Grizedale Sculpture Forest in England. As sculpted hydro-glyphs capture water for desert wildlife such as Scatter (1987), her floating art in the form of islands provides a welcoming habitat for all kinds of aquatic species, from turtles and frogs to ducks, herons, and songbirds, to swallows and insects. Her work is symptomatic of the great differences between environmental art and Land Art. As Suzi Gablik emphasizes: “Where early site-specific sculpture was in a sense a parasite of nature, absorbing surrounding beauty but contributing little to its continuity, Hull’s work functions within that environment, exchanging beauty with that of the surroundings” [7]. In other words, these artistic practices, by recreating certain natural realities, explore ecological questions of habitability and survival.

The abovementioned works do not reduce the dialectic of art and nature to nothing. On the contrary, the dialectic is reactivated within these new configurations that aim to consider art as a special product of nature. Nature as art is the art of nature.

Theodor Adorno writes in his lectures on aesthetics:

[…] one can say that art, by distancing itself from nature and thus no longer making itself the immediate object of desire but, rather, transferring the happiness of immediacy to the mediation of the imagination, always tries through this very act of immanent constitution to come to the aid of nature, to preserve something of nature, to give back to nature some of what belongs to it and is taken from it by the historical world. […] In other words, then — and I would say that this is really the true dialectical key to the relationship between nature and art: the aspect that nature is salvaged in art is inseparable from the fact that art is increasingly able to control nature […] [8]

This quotation sketches a reflection on ecological restoration. As Adorno relegates nature to being recreated by art, his words address questions that have divided the Anglo-Saxon philosophers since Robert Elliot’s famous article “Faking Nature,” published in 1982 [9]: Should ecological restorations be based on nature or art? Can they? These questions challenge us to rethink the relationship between a nature that we imagine as natural and an artificial nature, between a new creation and a “re-creation” that would simply repair the human acts that have damaged the planet and degraded it until today. Following Adorno, artistic practices, including those mentioned above, not only create new sensitivity to the natural nature but also propose new modalities of recreating this nature. Human intentionality, more specifically the human action in this recreation of places, is essential here. One might think that an analysis of place leads more to the idea of ecological impact (and therefore of responsibility) than to that of intentionality. However, while an analysis of ecological impacts presumes the deterministic apprehension of a chain of causes and consequences, intentional artistic practices allow us to reinterrogate our agency in relation to the place. The latter affords us more choices and freedom.

Terrestrial habitability in the eyes of Helen and Newton Harrison

In the 2000s, I came to the research creations of Helen and Newton Harrison. Their work on the global ecosystem was fortuitously born, in 1969, from the exhibition Fur and Feathers held at the Craft Museum in New York. Their installation piece An Ecological Nerve Center illustrates the destruction of threatened and extinct species. Subsequently, incorporating various disciplinary views featuring alliances with scientists and planners, their many projects in relation to issues of food and daily life raised the question of survival head-on.

Consider, for example, their first series entitled Survival Pieces concerning food production and daily life. These works put earth, grasslands, water, and living beings (mainly domestic) into the space of galleries or even museums. One of these powerful gestures is the spreading of soil to create a pasture in a museum space with the intention to introduce a pig (Hog Pasture: Survival Piece #1, 1970-71), which was eventually refused by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts which commissioned the piece for the exhibition Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. The artistic gesture is vulgar, not only in the sense that it refers to an animal symbolically loaded with pejorative and even anti-Semitic connotations, but also in that it refers to an ordinary animal, present in the back alleyways of cities, in the countryside, and on the plates of millions, perhaps billions, of consumers.

Other works in the series refer to agriculture, including fish farming. The Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece # 3 (1971), commissioned by the Hayward Gallery in London, generated a controversy. Catfish swimming in the pools were to be culled for consumption at the end of the exhibition. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals required professional fish farmers to electrocute these catfish, justifying this requirement as the only humane way to kill them. Despite the controversy the electrocution of catfish in a gallery raised, the fish were nevertheless allowed to be put to death for a feast during the presentation of the work to the British public. What is interesting is the discrepancy between the ethical questions raised by this piece as early as the 1970s and the lack of interest in this same action so common in our societies, namely the slaughter of animals. In Europe, only recently did denunciations of slaughterhouse conditions take the necessary step to re-examine animals’ welfare [10].

Since then, Helen and Newton Harrison have been inviting everyday ecological life into the museum space. Full Farm (1974) restages all these works and highlights their pedagogical dimension. The following Lagoon Cycle (1974-78) broadens the framework of their interrogation. From the outset, the Lagoon series, unlike the Survival Pieces, confronts the means of rendering visible terrestrial surfaces and the challenges of land use planning. In this work, their point of view is not romantic, as in the image of Joseph Beuys promoting renewed relations to the Earth and to the living, but ecological, in the sense of interrogating how we live and survive on the surface of this Earth. As they questioned the earth’s habitability, they also tried to find the terms for its representation. They staged a very large mural of a lagoon, on which diverse stories and anecdotes render a fake dialogue between two characters, a lagoon maker and a witness. In doing so, the Harrisons used various registers, including ecological scientific, political, and media discourse, to instruct the question: “What are the conditions necessary for survival?”

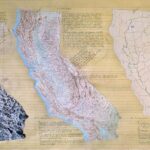

What matters most in the Harrisons’ installations of the 1970s is the use of maps, satellite photography, and misappropriated scientific schemas. Commissioned by the Floating Museum in San Francisco and exhibited for the first time at the San Francisco Museum of Contemporary Art, Sacramento Meditations (1977) carries out a reflection on rivers, a motif visited by many including the French anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus entitled Histoire d’un ruisseau (The history of a stream) but here used to highlight the contradictions caused by intensive agriculture in the valley of central California. The exhibition was twice on the cover of Art Week. The nine maps of the State of California shown in this work consisted of a drawing, a satellite photograph, a map of the political boundaries, as well as maps of water resources, irrigable lands, and topology. The following exhibit Art Park: Spoils’ Pile Reclamation, 1976-1978: Ongoing, commissioned by the Art Park Foundation, was different since its challenge to habitability is initiated by the request of local communities living in a degraded environment. To transform a quarry filled with debris generated by the construction of a power plant on the Niagara, the Harrisons suggested covering the waste pile with organic matter and soil to recreate a meadow environment with trees, and local communities provided truckloads of soil and compost. The site’s aesthetic re-creation in the end proved to be much less costly than regeneration undertaken by professional landscape actors.

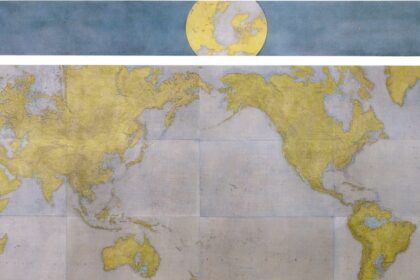

Baltimore Promenade (1981) by the Harrisons also deals with land use planning and confronts the physical splintering of urban and peri-urban sites in Baltimore. To improve habitability in terms of quality of life and of the city, they proposed building a promenade, a reunified transport artery that emphasizes the possibility of well-being. Their work also challenges failures in planning. Serpentine Lattice (1993) depicts California’s dying forests to question the preservation of forest cover from Vancouver to southern California. Through time, their reflections on land use planning became more grandiose and cartographic. Green Heart of Holland (1995) pursues reflections on terrestrial habitability at a regional scale. In this case, the Green Heart of Holland plans a vast farm centered on a ring of cities, here Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Utrecht, that will create a large central park for the cities that constitute an economic and cultural center in Europe. At the request of the Cultural Council of South Holland, the Harrison Studio developed a series of images – a combination of ceramic tiles, a map, a drawing, a video, and a discourse – to visually convey the need to radically preserve part of the land [11].

Their subsequent works continue to explore the idea of cartographic design on the scale of regional land use planning, but now in response to the idea of the ecological preservation of a territory. Peninsula Europe, started in 2000, depicts a Europe where land use has not changed towards more ecological planning. Plagued by droughts, it struggles to feed its people and turns towards Russia and Central Europe. The current crisis reminds us of the realism of this scenario. In Peninsula Europe III (2008), the artists imagine a new trans-European forest, based on the idea that complex and mixed forests in the available land can create a sponge phenomenon strong enough to provide, to some extent, the waters that were formerly supplied by the slow melting of snow and glaciers but might soon become unavailable. This intervention proposes an evolution of the geophysical system towards greater ecological stability, which would in turn strengthen cultural stability.

They have always considered the issue of climate change as they coopt scientific thinking and work in collaboration with civil society and local authorities. One of their earlier experiments, the Garden of Hot Winds and Warm Rains, started in 1996, includes two greenhouses, each with a temperature increase of 3° C, one modeling a more humid climate, the other more arid. However, as their work progressed, they realized that since irreversibility was already a fact, we would have to find practical ways to live with the more hostile ecological condition. Greenhouse Britain (2006-7) takes up the challenge of global warming from an artistic perspective. The work was divided into four parts. The first part consists of a model of Great Britain, a projection of rising waters onto it, and an audio text about what would happen. The second part is a representation of what people confronted by this phenomenon could do, while the third and fourth parts detail more solutions. It shows a utilitarian aesthetic combining a warning signal and an assertive proposal based on scientific information. All this reflection and work led to the creation in 2009 of the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In the center’s declaration of intent, “force majeure” was defined as the pressure exerted by global warming, exacerbated by industrial processes, on all planetary systems. The Harrisons advocated for the idea that artistic creation could have a global relevance by promoting eco-literacy through three actions: Provocation identifies the gap between where we are and where we need to be, conversations are fostered to identify solutions, and implementation, at the heart of these art practices, intervenes in the real world.

How can their works help us today to produce an environmental consciousness? How can they better inform the apprehension of climate change and the struggles and actions to be taken to respond to it?

Their research creations give us an idea of how we must allow ourselves to be free in some manner when facing the constraints and imperatives imposed by productivist and growthist thought that continues to hold sway despite the ecological emergency. The Harrisons’ artistic works bear witness to this freedom of thought and to a force of conviction at the risk of being marginalized in the world of art. Moreover, the Harrisons’ works in the 1980s promote a unique way of engaging with municipalities, nations, NGOs, and local ecosystems that went far beyond “site-specific” thinking and aimed to provide sustainable interventions in the urban environment and/or at a geographical scale. Their projects remind us that the place, the site, and the situation are essential starting points in the development of a narrative of human development which, while currently catastrophic from an ecological and climatic point of view, can also lead to repairs. In addition, these artistic interventions show the playfulness, the necessary creativity, and the sideways steps that must be taken to challenge the various ways that dictate public life and professional expertise. Finally, their works demonstrate the interdisciplinarity and cross-fertilization of knowledge essential for dealing with such complex problems. We should explore ways between disciplines, between technical worlds, and between manners of categorizing and learning. This position is all the more important when we note the inertia and enclosure common in the realm of contemporary thought.

Conclusions

An artist engaged in environmental issues is confronted with many questions: how can a place or a collection of places at different scales influence the practice of environmental art? What art can and should ensue? How do artistic practices produce a locality and its feeling? What are the links between the production of environmental knowledge and artistic practice? What are the generative intersections between academic research, artistic research, action research, and practical research, to name just a few? How can we deal with these questions while taking into account the multiple processes of material-discursive production, translation, transformation, and diffraction that shape research-creation practices? What are the methodological, formal, and epistemological challenges for environmental art? What aesthetic and tangible creation implies the implementation of this work program? The Harrisons have tried to answer these questions since the 1960s, progressively evolving through a practice mindful of itself. Other artists mentioned in the essay have also started to study and tackle the problem of terrestrial habitability. Their examination of the situated nature of art not only deals with the question of scale and interdisciplinarity but also forces one to reflect on the complexity of socio-natural dynamics. Such an observation obliges us to wonder about the alliances which are developed between living beings and elements of the surrounding nature, and more still to analyze, understand, and test how these alliances, these environmental forms promoted by the artists working in the field of ecology, inscribe themselves within limits while developing capacities of expression.

The erosion of the great variety of living beings, the rarefaction of resources, and the digitalization of our means and conditions of existence are the signs of a hybridization between the Technosphere and the Biosphere. Our time is an uncertain one, to say the least. What conduct should we adopt in these unstable spaces which are multiple and varied, some eternal while others domestic, mixing facticity and falsehood? These questions remain to be tackled by artists and theorists in the future.

Nathalie Blanc is Director of Research at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and Director of the Centre des Politiques de la Terre (Director of the Earth Politics Center https://u-paris.fr/centre-politiquesterre/) based at the University of Paris. A pioneer of ecocriticism in France, she has published and coordinated research programs on areas such as nature in the city, environmental aesthetics, and environmental mobilization. She has published several books, including Form, Art, and Environment: Engaging in Sustainability and Art, Farming and Food for the Future Transforming Agriculture (Routledge, 2016 and 2023). She is also an artist and curator, currently working on the theme of ecological fragility. Blanc has been coordinating since 2017 a project of LAB ArtSciences Le Laboratoire de la Culture Durable devoted successively to the urban soils of the Anthropocene (SOLS FICTIONS) and to sustainable food (LA TABLE ET LE TERRITOIRE) which gives rise to experiments in writing and exhibition (Domaine de Chamarande, 2016; Ferme des Cultures du Monde, Saint-Denis).

Notes

[1] Nathalie Blanc et al, Une Terre au défi de l’habitabilité, 2022. https://u-paris.fr/centre-politiques-terre/une-terre-au-defi-de-lhabitabilite/.

[2] Luke Kemp et al, “Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, 34 (2022). https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2108146119.

[3] The conditions for the habitability of plants and animals on Earth were only achieved with the gradual appearance of oxygen in the atmosphere over 2.5 billion years ago. The colonization of dry land, 500 million years ago, constituted a second stage in the habitability of the Earth with the appearance of soil such as we understand it today, a microcosm allowing humans to feed. A third stage was achieved with the development of the human species. In the natural sciences, the notion of habitability refers to the idea that systems can regulate themselves in order to maintain sustainability despite catastrophes that threaten them (volcanic, extra-terrestrial, etc.). In the social sciences, particular attention is paid to the way in which human societies colonize territories and organize themselves spatially, inhabiting these lands.

[4] Johan Rockström, et al, “Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity”, Ecology and Society 14 (2): 32, 2009. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

[5] Excerpts from Sue Spaid, Ecovention/ Current Art to Transform Ecologies (Cincinnati: Contemporary Arts Center, 2002). Published in conjunction with the exhibition “Ecovention” at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, June 21 – August 18, 2002, co-curated by Sue Spaid, Contemporary Arts Center and Amy Lipton, Ecoartspace. https://patriciajohanson.com/archive/ecovention.html#s4n4

[6] Patricia Johanson, “Cyrus Field,” Art and Survival (1992): 10. https://patriciajohanson.com/archive/ecovention.html#s4n4

[7] Sue Spaid, Ecovention/ Current Art to Transform Ecologies (Cincinnati: Contemporary Arts Center, 2002), 76.

[8] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetics, Cambridge (Polity Press, 1958-9), Empl. 2129.

[9] Robert Elliot, “Faking nature,” Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy 25, 1 (1982): 81-93.

[10] Denis Simonin and Andrea Gavinelli, “The European Union legislation on animal welfare: state of play, enforcement and future activities,” in Animal Welfare: From Science to Law, edited by Hild S. & Schweitzer L, 59-70.

[11] IPCC, 2019: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems.