Informal Art: The Scene for a Creative Resistance in Urban Life

Pouria Jahanshad

Translated by Reyhaneh Mirjahani and Saba Zavarei

In recent decades, after extensive arguments and debates, it seems somehow a collective agreement has been reached on the socio-political functions of art.[1] Marxist theory and critical studies related to art, which have long been overshadowed by the history and philosophy of art and psychoanalytic approaches, have gradually emerged, revealing new aspects of the functions of artistic mediums. Today, most artists who claim to be working in the contemporary art scene consider art to be a tool that can oppose a ruling power or a dominant political situation and even cause changes in them. In the meantime, many official and governmental institutions around the world speak of the influence of art in the realm of politics and directly or indirectly encourage artists to produce works with obvious political themes. However, evidence indicates that despite the optimism for contemporary art’s engagement with politics or what is called “political art” in the contemporary world, art is confronting a dead end or a vicious cycle. This suggests that even superficial paradigm changes in art from valuation based on the materiality of the artwork to valuation based on socio-political functions has not been able to emancipate the artist from controlling structures and art’s liberation.

There are many reasons for the general failure of contemporary art to fulfill its political promises and ideals, which I have tried to explain and analyze in this article by focusing on some aspects of the art and culture scene in Iran. [1] This article consists of two main sections. The first section is devoted to a critical analysis of the concept of “politics” in “political art” and also seeks to address why a vicious circle in today’s experience exists. But the second part will focus on presenting some principles and examples that I think can show some solutions to overcome the vicious circle of the formal politics of individuals involved in the art world. Since the foundations of this study are heavily indebted to some theories of informal life and critical urban studies, this approach can be referred to as the “informalization of art” and the type of art in question can be referred to as “informal art” or the art of ordinary people. This is the art that, despite the ups and downs in Iran, guarantees the continued influence of non-bureaucratic civil forces governing the city.

It is worth it to mention that the approach I propose in this article and my other writings as the “informalization of art” is a personal and ongoing project. This venture reflects on the political agency of art in society and the relationship between art, political and social change, and eventually the redefinition of art within a completely different framework from what is conventionally accepted among many artists, institutions, and art-related media.

A Reflection on the Concept of “Politics” in “Political Art”

Content-oriented classification of art based on the social or political content that the arts seem to have dealt with is a method that began decades ago and persists to this day. However, rather than revealing anything about the content of the artworks, terms such as “political art” and “social art” seek to consolidate and normalize the conceptual indications of being politically and socially shaped by the dominant discourses through naming and labeling artworks. This mechanism has led to the formation of a criterion in society for artists and filmmakers under these titles, and therefore a group of them have been named and even praised as social or political artists. Thus, it appears to be clear how we approach the terms “political” and “social,” but if we have a closer look, we see that by confining the meaning of these words to specific and determined forms of acts and relationships, we have excluded much of what can in fact be considered political or social. Instead, what remains under these titles has become politically neutralized, harmless, and has already been directed in certain directions, which their political roles can already predict.

To give an example, the local and even global perception of a socially engaged photograph or film is that these objects are doing nothing more than representing misery. These representations supposedly portray us through an image of a (typically Middle Eastern) victim caught in the midst of war and disease as a means to persuade people on the other side of the borders to support the depicted victim. These illustrations flaunt the power of the liberal discourse on human rights, which requires the image of the victim on the one hand and the good people and charities (mostly white and European) on the other—a discourse that we have blindly accepted as the only way to ward off evil from the world. Nonetheless, probably only a few of us have thought about accepting the affirmative role of human rights in the realization of some basic rights, as well as its key role in depoliticizing transregional relations and consolidating the superior and inferior positions of nations.

There is a similar approach regarding political art. Whether in the local or the global scene, when the political attribute is referred to as an artwork made in a particular society, the dominant imagination expects the work to be involved in approval or negation of the official policies of that society or country. It cannot be denied that this impression has been strengthened in an interactive relationship with the content of works called political, while none of the distinctions between these works have invalidated such impressions. If we consider our country Iran, the opposition to the official policies inside or outside the country call the works that approve of these policies “propaganda-sovereignty,” while the advocates of these policies call the artist who has taken the opposite side “the opposition” and probably sees their work as slanderous.

Here a question may be raised for the reader: despite the contradictions within the sovereignty and the polarity of the opposition, can the duality of “sovereignty/ opposition” be formulated and become inclusive to contain all of the artistic scene? To answer this question, we need to explore the concept of politics. Politics means a set of agreements, contracts, and institutionalizations that establish a particular form of order in society. The establishment of this order is always with the rejection and denial of other rival forms. Looking to Jacques Rancière’s notion of police order, this form of order leads to a specific distribution of social forces and places certain groups in a dominant position and others in a subordinate position, while each of them is situated in a specific type of life.[2] This particular type of regulation is dependent on certain forms of seeing, being, confirming, or denying, or in better words, is repentant to a particular form of conceptualization and social valuation. In fact, when talking about politics, what remains important is the specific configuration of conceptualizations that have a neutral and natural appearance, but beneath their surfaces lurk the skewed interests of those groups close to power. Meanwhile, it should be noted that the political in today’s world does not mean obvious exploitation of individuals, but a form of organization that exploits individuals and groups in a seemingly natural way and intangible form.

Therefore, politics either as a sovereignty or an opposition, is dependent on certain forms of discipline, exclusion, and suppression that in the end do not create much difference in its nature whether it is sovereign or not. Politics in either pole of sovereignty/opposition is constantly created and revived by the influence of another pole, and it is completely encrypted by the supporters of both poles. For this reason, even though there is often no homogeneous policy as a sovereign policy and opposition policy, the impression of homogeneity of each of the two poles is encrypted through artistic productions in these encoded fields. The consequence of this encryption is a kind of obvious replication of the supposed forms of resistance. Such similarities can be clearly tracked in the seemingly political productions of art and cinema, which gain attraction in many festivals and exhibitions outside Iran. Consequently, many artworks that are considered political, depending on their institutional support, are direct responses to the conceptualizations and values of the actors of the other party, while at the same time their existence is dependent on the survival of that opposite pole.

Evidence suggests that adopting any political identity associated with nationality, ethnicity, gender, and religion by an Iranian artist is not measured according to the dichotomy of sovereignty/ opposition and that artist cannot easily succeed in the global art market. One of the most prominent examples of pure surrender to this political dualism can be found in the course of the seemingly critical art that has been shaped by Iranian artists throughout the 2000s, inside and outside its borders.

During the 2000s, due to the expansion of communication networks, the apparently impermeable fortress of Iran gradually crumbled, and the West attempted to satisfy its desire to discover this new object through art. The eagerness to discover this unknown object along with the urge of the West to create new art markets and the capability of the new generation of Iranian artists working with new media helped to form a reciprocal communication between artists and western art organizations, which ended in the birth of supposedly critical art. Following this move, the first theme that appeared was people. People who were absent for more than two decades from the canvas, the negation, and even literary writing, were summoned back to the scene to legitimize the art sector that claimed to be political. But the people who were realized by artists this time most of all, were like an amorphous mass that was the manifestation of the ruling ideology and the embodiment of class ignorance, contrary to the mythical image depicted during the war and the Revolution.

Undoubtedly, the main function of this portrayal is to construct an image of the people as the backward Other, which stands in contrast to the superior position that the artist depicts him/herself as occupying. From that very same transcendental position he/she looks down at the (poor) people. Relying on this constructed imagination, which is based on the demarcation between self/people, intellectual/backward, and artist/non-artist, the artist tries to position his/her self at the center of political opposition. For this reason, the gender politics of an artist such as Shirin Neshat requires the representation of the people be a disfigured, ideological, and passive mass, so that the people as an embodiment of authoritarian rule, reproduce the negative pole of sovereign versus the positive pole of opposition. In addition to Shirin Neshat as one of the most famous figures of this type of illustration, similar attitudes towards the objectification of the people can be seen in the works of artists such as: Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh, Shadi Ghadirian, Sadegh Tirafkan, Siamak Filizadeh, Mehrdad Mohebali, and others. However, some of these artists, due to their residency in Iran, avoid unifying the people and sovereignty and prefer to stay safe by avoiding political labels on their works by resorting only to a kind of ironic exoticism.

In general, the people in these seemingly critical works guarantee two different types of capital for the artist: social capital, which is achieved through a clear demarcation between the intellectual artist and the people supposedly immersed in ignorance and backwardness, and economic capital, which is a reward for satisfying the ostentatious and superior desire of the Western subject and is obtained through the artist’s aesthetic exploitation of the people. It is interesting that this portrayal of the people—that the seemingly critical artist is not interested in and probably does not have any understanding of—becomes the popular figure for the artist at the time of political uprising. Because in such situations, the artist is given the opportunity to demarcate a group of people against another group and take advantage of the waves of protests. This is almost what happened after the 2009 presidential election, when the representation of the (poor) people was suddenly replaced by revolutionary portraits of them, the eruption of green canvases, and the mystification of the victims. However, the actions of these captive artists in the dead end of political dualism were not limited to the artistic mediums and the period of popular protests. Many familiar images and icons of the protest movement adorned the bodies of seemingly critical artists, artists who make every effort to perpetuate the emerging market of protest/exotic art and to establish themselves as the new leaders of the artistic opposition, even long after it was shut down.

The Transition from Political Art to Living Politics as “Art”

So far, everything that has been discussed has dealt with politics as a form of order and at the same time a form of rejection. It is clear that in this pervasive concept of politics, political art cannot get rid of the existing encrypted field. To discard the sovereignty/opposition dichotomy, we must move beyond the concept of politics as an institutional and police order, whether on the ostensibly sovereign or oppositional fronts, and think of other forms of social organization that can create a political subject. Jacques Rancière’s interpretation of politics looks at an antagonism that challenges the existing order as a kind of consensus and replaces it with dissensus.[3] Regardless of whether consensus is on the side of sovereignty or opposition, it tries in a totalitarian way to encrypt and appropriate all hypothetical types of political actions and behaviors. For this reason, the only way to achieve new forms of resistance is to move beyond any artificial consensus on both sides of the pole, by embracing a different interpretation of politics. Thus, the artist with a vision of social change has no choice but to resort to some kind of “informal politics.”

But the point is that the connection of art to the realm of informal politics undeniably jeopardizes the recognition of art and a work of art. The symbolic place of art and the artist in the global system is heavily dependent on the media, institutions, sponsorships, private banks, and temporary and permanent markets, almost all of which follow the same formal and dual policies. Therefore, for an artist, informal politics means ignoring the mechanisms that have given him/her the status of an artist, a reputation that on the one hand distinguishes him/her from non-artists and on the other hand, in the system of social division makes him/her a producer of a certain kind of goods-branding for the affluent classes and possibly the nouveau riche.

Despite these dangers, due to the constant encryption of the field of political art, it does not seem possible to achieve creative forms of politics, except in the shadow of successive demarcation with the institutions of power and capital, as well as the disillusionment of the artist/non-artist duality. On the one hand, it is only by achieving these conditions that people’s creative politics in everyday life—as an artistic act towards social change—deserve attention, and the creative political actions of artists outside of institutional values and market systems can find real criterion for judgment. This seems to be something that the Situationists and their main strategist, Guy Debord, understood well decades ago.[4] In The Situationist Movement, Patrick Marcolini writes:

The understanding of the art of the last two centuries is made possible by the understanding of the political movements with which it is associated. Although there are many ways of this connection, all of them can be traced back to the two-way movement that Walter Benjamin summed up in 1939: the aestheticization of politics, the politicization of art. Nevertheless, in the twentieth century, the Situationist International presented an exceptional case of the total fusion of art and politics through the common transcendence of both concepts. The goal of the Situationists is to go beyond art by opening the field of behavior and situations of daily life towards free creation. What is urgently needed to achieve this goal is to end the division of art, which in itself has two meanings: the elimination of the separation between artists and spectators in order for everyone to be the creator of their own life; as well as the elimination of the separation between the arts in order to unite all the arts in the way of producing and producing life as a work of total art.[5]

Marcolini’s description shows that the Situationists were well aware that the liberation of art, which was completely immersed in the mire of the market and capital, and the liberation of a society deeply captive to the spectacle were strongly interdependent and any attempt to liberate only one was barren and abstract. For this reason, the Situationists’ project is known as a revolutionary undertaking in which the definition of art is nothing but creative politics in everyday life; politics, which not only lays at the foundations of the May ’68 Revolution, but also manifests itself in strategies of occupying places, writing slogans, and appropriating the city and the streets.

On the other hand, if we look at the historical evidence from the period when art in its contemporary sense emerged, we find that in the most ideal formulation, what is called art—regardless of the defined art philosophy framework—has qualities and functions in connection with aesthetics as a distribution of the sensible [6] and of the genus poiesis (discovery and creation) in terms of conveying a different way of looking, a different manner of configuring things, and regulating and making the other kind of world orderly and visible.[7]

It is precisely because of this interventionist function of aesthetics that the term politics of aesthetics takes on meaning and credibility. If we pay attention, we realize that the axis of the politics of aesthetics and the main axis of all its qualities and related functions can generally be categorized as creativity. But this creativity does not take an abstract form as in solving mathematical and scientific problems or in the general sense as the essence of human existence. Rather, it is the product of a dialectical relation that is entirely concrete to material situations that have their own nature and history. This form of creativity is generated when encountering pre-encrypted goods or normalizing rules of social control and repression.

“Informal Living” and “Informal Politics”

Over the past decade, much of human creativity in the urban environment has been made visible by the newly established knowledge of “Urban Informality as a ‘New’ Way of Life.” Interestingly, most scholars in this field, including Asif Bayat, Parta Chatterjee, Arjun Appadurai, and Solomon Benjamin, who have bridged informal living and postcolonial studies, focus their research on the Middle East. Chatterjee refers to the bargaining and negotiation of the marginalized in Calcutta and their negotiations with political parties.[8] Appadurai’s essay “Deep Democracy” deals with the ability of disadvantaged groups to acquire land, infrastructure, and services.[9] Benjamin, in the sense of “Occupancy Urbanism,” discusses groups that not only seize the surplus real estate market by claiming land ownership and running small businesses, but also endanger the markets of transnational corporations. Benjamin argues that occupying urbanism even brings a kind of political self-awareness to its subjects that they no longer submit to the NGO mechanism under which participatory planning takes place.[10] According to these thinkers, these “informal politics” have been able to improvise the word “politics,” which has been severely exploited and manipulated in recent years, in order to contrast the informal politics of ordinary people with the formal politics that is constantly reproduced in the media.

The studies of “urban informality as a ‘new’ way of life” show that informality is a form of disrupting order through the parallelization of social relations, power relations, and a form of disruption of the global economy on a local scale. These studies also show how ordinary people, in their interactions with each other and in local policymaking, achieve their goals of self-government without the need for the so-called “experts” in the social division of labor. One of the advantages of informality is that it is ignored and denied by the established powers, which can lead to various parallels and further disturbances in the existing order. Thus, informality can be described as a general strategy that is not limited to marginalized groups and has many suggestions for creative politics in everyday life. Undoubtedly, this is the point that connects the studies of informal living as a way of life to the views of the Situationists.

Art and the “Informal Artist”

If we accept the slogan of the Situationists that the emancipation of art depends on the emancipation of societies, then art that longs for freedom and emancipation can be nothing but creative politics in everyday life. However, we have already learned that power discourses strongly seek to encrypt and formalize any kind of politics, whether agreeing or disagreeing with the status quo. Thus, the contribution of studies of informal living as a way of life to Situationist theory is the revelation of new fields for resistance and creativity. It is clear that these new fields manifest themselves only in the context of comprehensive informalizations including: informalizing politics, the informalization of art, and informalizing spatial practices. This is what ordinary people seem to do far better than formal artists and politicians. Because ordinary people, especially the urban subalterns—unlike professionals and the formalized—are on the margins of the social labor division system. This marginalization or informality allows them to carry the actions and be the narrators of the sub-narratives and sub-histories that disrupt the formalization project. For this reason, when these informals take up a camera or pen to record an event, they open up another world to us because they are unfamiliar with stylistic rhetoric, semantics, and broadcast rhetoric. Rather, they depict a world that clearly leaks through still and moving family images or what occurs on the street, thereby distinguishing their portrayals from formal imagery. This issue can be verified well after the recent riots in Iran through people’s mobile images.

This may lead to the misunderstanding that all people who are considered artists, in the context of theorizing informal art, are supposed to give away their place to ordinary people who are deprived of artistic taste and knowledge. Clearly this assumption is false, because what is at stake in the informalization of art is not the denial of artistic knowledge or expression, but the denial of specialization and the disregard for the social division that is directly related to the mechanisms of the art market. Even the Situationist radicalism did not seek to remove artists from the cycle of creative urban activity, although both in theory and in practice, the need for a different understanding of art was emphasized.

Undoubtedly, the modernized translation of Situationist and informal living theories have attractive proposals for the participation of the bearers of artistic knowledge and those who are deprived of it. In this context, we understand participation not as teaching people the tools and history of art, but as co-producing knowledge and learning together. This type of participation is precisely the process that is seen in the Situationist movement and also has been experienced in recent years in informal settlements in India, Brazil, Venezuela, and other parts of the world. Regarding Iran’s 1979 Revolution, where Asef Bayat writes about the creative actions of the people, no one knows exactly how many individuals from the groups involved in creative politics in the city center wore the symbolic label of artist and how much of their knowledge was used.[11] But it is clear that the symbolic capital of artists was not to be used in street politics and the occupation of streets and vacant houses.

“Informal Art” After the 1979 Revolution

It is a mistake to assume that informal politics ceased after the Revolution and that informal artists, whether uneducated or well-educated in the arts, ceased to engage creatively in everyday life. A brief review of contemporary history in Iran shows that from the very beginning of the 1980s, various forms of informal art were formed. It is beyond the scope of this article to mention all of them, but some of these creative actions will be briefly discussed as supporting examples of this argument. Some of these actions, especially those of the first decade of the revolution, may seem trivial today due to their extreme simplicity and pervasiveness in society, but as we get closer to the present, the delicacy, innovation, and demandingness of these actions increase significantly. In many cases, these actions have inspired formal artists who claim to be socially active, and this has challenged the work of informal artists to prevent the recruitment and castration of these actions.

If we go back to the Iran-Iraq war and the era of the widespread ban on communications and the ban on the use of new technological tools, the traces of fascinating forms of creative politics that might be included in the framework of survival policies become clear. During this time, families used familial ties and national holidays as excuses to celebrate, despite the anxious conditions of the war and the loss of loved ones. Although there were serious obstacles to holding these celebrations for reasons such as the mixing of men and women, the type of clothing and illegal music, these obstacles did not cause the slightest disturbance to the joyful will of people. On the contrary, the creation of these governmental barriers led to the formation of new initiatives in the manner of holding these celebrations and the use of video technology, so that the images of these celebrations could be reproduced as soon as possible and shared with friends and relatives. In fact, ordinary people not only did not submit to the security conditions, but also used the technology that was banned at that time (video) to infuse the spirit of happiness, life and hope into the war-torn body and the security atmosphere of the city. These creative resistances, after a while, indirectly shortened the wall of prohibitions against family joys and video technology, and the negative encounters with new technology gradually gave way to a kind of neglect.

But after the Iran-Iraq war, the situation changed a lot. In the urban area, municipalities, in line with free market policies, quickly moved towards unbridled self-government, and over time, people lost control over the city and the concept of the neighborhood faded away. The idea of municipal self-government, which goes back to the Constructive Government (during the presidency of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani in 1989-1997), gradually turned the municipality into a giant entity that its seemingly legal financial means and power in practice prevented clear oversight of its very performance. The result of this unbridled self-governance was the complete takeover of the public sphere and the commercialization of the city, along with the widespread expropriation of the people. In addition, following the protests of 2009 and with the cooperation of some urban planners and consulting engineers, obvious physical changes were implemented in cities such as Tehran, the most important goal of which was to prevent similar incidents in the city. By enclosing squares, removing urban plazas, systematically directing people underground, and tangible and intangible control of the streets, these plans played the greatest role in making the city more secure and disciplinary. However, the evidence shows that such efforts by the city’s rulers did not discourage citizens from fighting for their rights, and that informal artists still have alternatives to transgress the situation.

In recent years, parkourists, dancers, street musicians, graffiti artists, and peddlers on the one hand and women who can be part of this chain or independent of it, on the other hand, have once again changed the arena of everyday life into an arena for bargaining and creative politics. However, during the last decade pressure has increased on some social groups and we in Iran have witnessed more radical politics pursuing specific people as more serious demands are being made by these groups. For example, the highly performative policies of women against forced hijab in public spaces and the emergence of mobile applications and alternative mapping technologies that alert women to the deployment of security forces in urban areas have emerged.[12] Here I need to emphasize that the forms of women’s creative politics in the urban space have been very wide and diverse for the past forty years and addressing them requires another opportunity. But I would also like to point out that these policies have been so effective and mobilizing that it is not unreasonable to consider the gender of creative resistance in the city as female. Female in the sense that only women’s bodies weigh heavily on the indifferent body of the city in the realms of struggle, demand, and litigation, and it is only the female body that is thus abused and regains its growing agency thereby disgracing the hollow theater of power and authority.

Below, I introduce the final example of this discussion, focusing on one of Tehran’s neighborhoods. I want to show how informal art agents have been able to interact with each other to achieve their goals to an acceptable level. The basis of the information obtained in this section is some scattered research or information obtained directly from the activists themselves.

The Araj neighborhood of Tehran is one of the neighborhoods that has been able to differentiate itself from many others in Tehran by relying on the creative forces of the people and attracting their participation. The formation of this distinction stems from an adjustment made by the entry of some knowledgeable and creative local actors into the Neighborhood Council of the urban bureaucracy. The connection between these semi-formal politicians and the informal/non-bureaucratic politicians of the neighborhood led to a path that can be called participatory activism. Manifestations of this creative action can be identified in various fields from the mid-2000s to the present day. Probably one of the most creative forms of participation in the Araj neighborhood is the preparation of a participatory map of the neighborhood, which was prepared by a population of nearly 200 residents with basic tools such as yarn and colored paper used in public places such as sidewalks, parks, schools, and mosques. Although this map bears similarities to conventional maps, it is in fact a social and strategic map that has recorded and written down the sensitivities and priorities of the people. In addition to identifying local hangouts where people gather and exchange ideas, the map also indicates dimly lit, high-risk areas for pedestrians in the neighborhood with, for example, steep slopes and places where women may be harassed. In fact, the most important advantage of such a plan is to summon and enumerate anything that is only noteworthy from the point of view of the people.

Another example of the participation—albeit secretly—and the creative resistance of the residents of Araj neighborhood can be identified in connection with the renaming Golzar street. Hadi Kashani, the secretary of the Araj neighborhood council, describes this issue as follows:

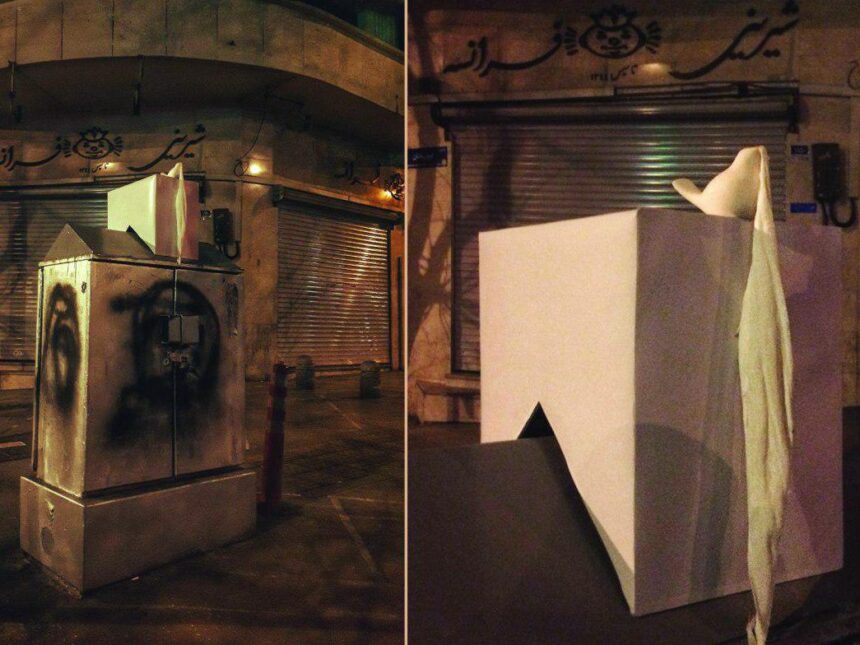

Two years ago, at the request of the family of a martyr of Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), who had recently settled in the Araj neighborhood, the signs on this street were changed from Golzar to “Shahid Mesbah.” After this incident, successive painting was started on the signs bearing the title of “Shahid (Martyr) Mesbah” street. In the next step, the residents of the street took the initiative and wrote the name of Golzar street on the walls of their houses. Some residents also prepared a stencil and used the stencil to write the name Golzar. These splashes and objections were so great that the district municipality changed the signs on Golzar street twenty times and finally they were convinced that there was no other way but to return the name. Golzar is no longer on boards. Currently, the district municipality has retained the title Shahid (Martyr) Mesbah as the original name on the sign and has added the phrase “former Golzar.” The objections, however, are not over yet, and now it is only the first part of the text written on the board that is carefully crossed out.[13]

Conclusion

An examination of the cited instances of informal art shows that these creative politics have important features and commonalities that I refer to in this conclusion. Briefly:

- Informal art is problem-oriented and relates to concerns and desires that have a concrete aspect.

- Informal art is urban and environmental.

- Informal art operates—to a large extent—outside the encrypted and formal boundaries of political action.

- Informal art is the art of ordinary people—whether benefiting or not from artistic knowledge—that is not reflected in the specialty-oriented discourse and the differentiating mechanism.

- Informal art can be castrated and commodified by exploitations resulting from the aestheticization of politics and also emptied of content. Artists and art institutions play the most important role in this process. As can be seen, the subtle forms of resistance in the first decade of the Iranian revolution in the hands of filmmakers and some official artists in the form of kitsch art on the walls of galleries and a kind of game nostalgia have been transformed on the screen.

Informal art has more or less melancholic features:

- It is the result of the lack, prohibition or loss of something or the idea of losing something, as a mourning for that thing that has been lost or has never existed.

- It has a masochistic aspect, meaning it is the embodiment of absence in addition to the creative production.

- It has a metaphorical function, because the consequence is a form of prohibition, repression, control of society, and is an alternative to the forbidden or the unspeakable. In other words, informal art is a “thing” and not an object or commodity. However, in today’s world, it can easily become an object or a commodity and be integrated and exchanged in the vast apparatus of art.

- The melancholic features of informal art are collective and therefore has sociological, rather than psychological aspects. This means that it flows in the lives of different social groups and is not the result of mental sparks or individual and family traumas, and as a result, it promotes collective dreams and is not healed individually.

Pouria Jahanshad is an educator and researcher in critical urban studies and contemporary art. In recent years, his primary focus has been the interrelation between art, the city, society, and the creative mechanisms of practicing politics. He has published widely on urban studies, contemporary art, as well as documentary and experimental cinema. His four-volume collection Critical Rereading of the City is under publication.

Notes

[1] The following article is an excerpt from a detailed analytical article I wrote earlier and will soon be published by Roozbehan Publications, along with other articles, in the form of a book entitled Reading the City: Urban Governance.

[2] Jacques Rancière, “The Paradox of Political Art,” Dissensus on Politics and Aesthetics, translated by Ashkan Salehi (London: Continuum, 2010).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (1967), translated by Behrouz Safdari.

[5] Patrick Marcolini, Le Mouvement Situationniste: Une histoire intellectuelle (Montreuil, Éd. L’Échappée, 2013).

[6] Rancière follows the concept of “aesthetics” from the perspective of Kant’s book The Critique of Pure Reason and not The Critique of Judgment, which means aesthetics in relation to taste and beauty.

[7] See Asef Bayat “Street Politics: Poor People’s Movement in Iran,” Street Politics, translated by Asadolah Nabavi Chashmi (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

[8] Parta Chatterjee, The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

[9] Arjun Appadurai, “Deep Democracy: Urban Governmentality and the Horizon of Politics.” Public Culture 14, no. 1 (2002), pp.21-47.

[10] Solomon Benjamin, “Occupancy Urbanism: Radicalizing Politics and Economy Beyond Policy and Programs,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 3 (2008), pp.719-729.

[11] Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, second edition, translated by Fatemeh Sadeghi (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013).

[12] In addition, there were anonymous creative designs that sought to circumvent and neutralize the obstacles that the military posed to the placement of women on the platforms.

[13] Hadi Kashani, 2016.