Dancing into Alternative Realities: Gender, Dance, and Public Space in Contemporary Iran

Saba Zavarei

She dances on a car roof. The doors are left open and loud music is playing; instrumental, with no words. She sways gently then pauses to fix her mandatory hijab on her head, tying the scarf behind her neck. Limited by the edges of the car roof, she slowly swings her body. Behind her is a big urban roundabout. A high-rise shopping mall on the other side of the square visually echoes her upright body. An old woman smiles as she passes by. A few other people pay no attention. In another video, captured from another angle, a crowd of around twenty people have gathered on the pavement. Facing them, she calmly taps her feet, as if performing on a stage. Her audience makes indistinct comments. She moves in silence. There is no sign or trace to suggest what her motive is, if any. Nothing to help her confused audience interpret what they witness, other than a dancing woman on a car roof. The music stops. She bows. This is the end of her performance.

In a city under the constant pressure of economic crisis, widespread corruption, and heavy socio-political oppression, this woman’s dancing body ruptures the darkness and radiates hope by embodying a different world, and dancing another possibility. She occupies a fleeting moment of change, and cuts through the patriarchal norms of a geography that excludes her very body from being the “somatic norm”.[1] Like an embodied collage, her performance creates a surreal contrapuntal juxtaposition between what has been lost, and what has not yet been realized. No one knows her name. No one knows what happens after those twenty odd seconds of video recorded on people’s phones. All that is known is that this is Shahr-e Rey Square, South Tehran, April 2021.

In recent years, dance as protest in the Middle East has emerged as a subject of study for a number of scholars, working across a range of different disciplines. Writing on the representation of Iranian women dancers, Sepideh Zarrin Ghalam and Elaheh Hatami (2017) argue that public dance practices can be interpreted as “political acts,” where women “continue to question the dominant spatial and political orders and create alternative spaces”. [2] In their analysis of a video that went viral of a woman dancing in Tehran’s metro, and of similar videos, they argue that these acts do not aim at the grand political gesture of toppling the ruling power. Instead, “[t]hey seek to legitimize their own place in both urban and public spaces and reclaim women’s right to the city”. In another study on dance protest in Turkey, Susanne Foellmer writes that choreographic and dance practice can become “media for the alternative use of public space,” through “playful tactics and by rendering unclear the boundaries between everyday, artistic, and political behavior.” [3] These acts use the “locations of power for alternative purposes and reformulate them”. Therefore, these places can, for a period of time, be literally rewritten and re-choreographed. As she continues, “[a]rtistic practices can, then, become agents in the true sense of the word: performative, biopolitical mediators of protest that can, at least temporarily, subvert established boundaries of political behavior and systems.” [4] Dancer and researcher Heather Harrington (2016), writes on how women in the Middle East use site-specific protest dance to “challenge the sanctioned beliefs of how they should appear and move in the public space”. She argues that these performances that intervene in everyday life and “protest against the prescribed movements of the public space,” in order to provoke “an alternative to the defined, acceptable movement of people in public spaces,” thereby forcing passersby to “be present, and see their surroundings in a new way, shaken out of complacency by a fresh perspective.” [5]. She argues that such acts provide women with the possibility of being seen and heard, in contexts where they are marginalized and excluded from decision making:

Dance can change the meaning of a public space, and therefore change the social dynamics that are played out in that space. Social hierarchies can be broken down by infusing new meaning to the parks, subways, or a financial district through movement. [6]

During my decade of research on transgressive and out-of-place performances by women in Iran, I have come across other artists who take their dance practice to where it is banned, the street. In this article I explore the return of women to public space in Iran and how, in the absence of the possibility to be part of the formal art scene and in order to challenge normative geographies, artists, as well as non-artists, have taken to the streets to redefine and rediscover female bodies in urban geography. The disobedient body, I argue, creates heterotopian spaces where the hegemonic order is interrupted and replaced by an alternative aesthetics. Initially introduced by the philosopher Michael Foucault, heterotopia has been discussed widely in performance studies to explain the experience of place created through performance that “enables audiences to discern some hint or inkling of another world, even one that is otherwise invisible”, as Joanne Tompkins writes; and it “provides the potential for spatialising in performance both visible locations and, paradoxically, invisible locations (those which we know and those which we imagine).” [7] While all forms and means of official art remove, cover and hide away the representations of the dancing body–the female dancing body in particular—the practices I examine unsettle the dominant “distribution of sensible” in the words of French philosopher Jacques Rancière, in order to perform another city. The dancing body here distances itself from metaphoric and symbolic representations and embraces the realness of “performance action”, which is about “the direct presentation of voices, but it is also about confronting power, about location, and about the connection between that action and a wider struggle” as Paula Serafini explains. [8]

By analyzing the works of four practitioners, I explore the dancing body on the streets, demonstrating how the random dancing of anonymous individuals found on the internet can become a tactic of resistance for both the performer, and the viewer. Turning away from formal art spaces, I look to the streets for practices of resistance. I interpret these brief manifestations of dancing bodies on the internet as a form of socially-engaged art that questions the restrictive codes and rules of public space regarding female bodies. I analyze dance through the lens of performance studies, rather than distinguishing different choreographic genres and styles. While the story of each dance tradition in Iran merits due attention, here my purpose is to focus on dance and bodily movement in public in a more general sense. My objective is to explore the relationship between space, body and gender, by examining dance performances in public spaces in Iran. By refusing the categories of ethnic, folk, Western and other dance types, or the dichotomy of high art vs. non-art, I focus on what all these dancing bodies share: mutual exclusion and oppression by the state, as well as their resistance through evasive occupation of public spaces. [9]

A Long Story of Struggle

The struggle of the dancing body in Iran has a long history. Some scholars believe that the negative attitude towards dance goes back to the pre-Islamic period. [10] To contextualize my research and provide a better understanding of the contemporary situation I here examine briefly the troubled trajectory of dance and gender over the past century. It is believed that during the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925) the restriction of women’s participation in music and dance increased. Previous to that during the Safavid era (1501-1736), according to Ida Meftahi, female dancers participated in public performances, however, in the Qajar era, “mainly transvestite male adolescent dancers (bachcheh-raqqas) performed dance publicly,” while “the public dancing bodies [of women] performing for male audiences were commonly associated with overt sexuality and prostitution.” [11] Sasan Fatemi, Iranian ethnomusicologist, explains that these restricted boundaries between “male and female musical domains” should be interpreted as “a kind of return to the prevailing trends of the pre-Safavid period.” [12] He depicts the situation in the late Qajar period where:

[. . . ] female musicians were restricted to the andarun (or the andaruni which was the part of the house reserved for women) and men were obliged to gratify their desires by watching the young dancing boys who had also been prevalent in the past. [13]

With the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925, conditions were altered yet again. This change concerned mainly the spatial organization of gendered bodies:

Relatively speaking, kashf-e hejab [the forcible ban of the hijab by Reza Shah in 1936] removed boundaries that had segregated men and women in the audience space. From this time on, women appeared unveiled in the audience; in the beginning, they were most likely separated from the men (albeit without the use of curtains or related devices), but later on, they were probably seated beside men. Also, men in these groups who had been playing women’s roles in plays or dances were replaced by women. [14]

In the decades that followed, the state not only recognized dance as an official and respected art form, but it also supported women’s participation in a particular dance style, inspired by both Iranian ethnic and modern Western dance. This new hybrid dance form had been introduced as the Iranian national dance, as part of a nation-building project by the Pahlavis. Consequently, a division emerged between the highly respected dancer who was a representative of the nation, and the raqqas, in other words the oversexualized female body, often portraying the “fallen woman”. The former was performed in prestigious halls, the latter dominated the commercial cinema. In her insightful research on dance in modern Iran, historian Ida Meftahi writes:

The raqqas also became the main dancing persona of Lalehzar theatres, replacing the national dancers as the now governmentalized “national stage” moved to other areas, mainly the prestigious Rudaki Hall. Her image also dominated the widely seen commercial film industry of film-i farsi, replacing the ballet-trained dancing bodies which were formerly featured on the screen. The popular private-sector entertainment and cinema industries largely relied on the bioeconomy of dancing bodies which saved them from bankruptcy by selling overt performances of sexuality. [15]

Soon after the 1979 Revolution and establishment of the Islamic Republic, dance was banned. Following the denouncement by the Ayatollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic, of dance as frivolous, “the Iranian classical ballet company, the national folk-dance ensemble and all forms of public dance were dismantled,” according to Parya Saberi. [16] Consequently, dance practice, as well as dance education, was pushed back indoors to supposedly safe private spaces. Meftahi explains that eventually, a “renamed version of national dance” returned to the stage: “rhythmic movements (harikat-i mawzun), with mainly religious, ‘revolutionary’ (inqilabi), or mystical themes”. The choreographers and performers were often engaged with the main dance organizations of the pre-revolutionary era now had to repurpose their dance practices as religious rituals. [17] She further elaborates on how in this process, folk dances were renamed as “ritualistic” (a’ini), while the performances mostly excluded women and young girls. [18] It took almost two decades for a dance event to be performed publicly on stage [19]. In a more recent turn, collaborations between dancers and choreographers based outside Iran, mainly in the West, have increased in the private spaces of individual people’s homes, or mostly underground settings. [20] Dance has begun to creep back in and to occupy the public scenes from which it was removed, but during the past four decades, dancers have also been working under the constant threat of persecution and prison. Although the Islamic Republic has never criminalized dance in the penal code, in practice it has prohibited this art and activity from being performed freely in public. If a woman (in some occasions men too) is caught dancing in public, or gains too much attraction through social media or other ways, she can be persecuted for “acting against national security” and “dissemination of propaganda against the regime”; the Islamic Republic has been using such vague charges for so many activities to criminalize them on one hand, but also leave so much room for interpretation for itself to decide on what, where and when can be perceived as a crime.

Here I will cover some recent incidents by way of case studies, in order to provide an illustrative analysis of violations enacted by the regime against dancers in Iran. In 2017 six Zumba instructors, male and female, were arrested for “trying to change young people’s lifestyles” and “normalizing removing hijab”. [21] In 2018 Maedeh Hojabri, a 17-year-old teenager, was arrested because of the dance videos she published on her Instagram account, which had over six hundred thousand followers. In a confession which is believed to be forced, released on state television, Hojabri expressed regret: “I understand that dancing is an art but it should not be shown to everyone”. Around the same, time some other pages belonging to other female dancers disappeared from Instagram, among them Persian Cat and Sahra, both Shuffle dancers with thousands of fans. Sahra often used to dance in the streets and her videos of dancing in different parts of Tehran can still be found on the internet. While nothing was officially announced about the removal of these pages, it is not difficult to connect the dots and to realize just how much pressure women dancers are under not to invite attention on social media, or in any other way. Even though there is some relative tolerance for the ethnic and folk dances of different regions, and in some areas such as Kurdistan of Iran dance for men and women is an inseparable part of social life even in public spaces, women and girls still suffer more from exclusion generally. In 2018 the Mayor of Tehran attended a ceremony for International Women’s Day where schoolgirls danced on stage to live Iranian folk music played by women. The hardliners criticized him harshly for having been in the presence of female dancers, an act which was “against public decency,” and the Prosecutor-General ordered the prosecution of these “taboo-breakers” [22]. Although dance in public seems to be forbidden for everyone, the gender aspect is absolutely undeniable and “[p]rofessional female dancers are regarded as invading male space and raising unlawful passions through their dancing.” [23] There are other examples. In August 2020, composer Mehdi Rajabian was detained for collaborating with female singers and dancers in his work. Helia Bandeh, the dancer and dance researcher who performed in his project from abroad, had to flee Iran two years before, following the raiding of her workshop by police, and her subsequent arrest. [24]

As many scholars have pointed out, Iranian society is uneven and diverse. There are more conservative elements of society who find dance a negative “symbol of behavior”, carrying “the potential for social disruption”. [25] But for large segments of the Iranian public it is an inseparable part of daily routines and “an important means of expressing joy and happiness in socially approved contexts”. [26] As Anthony Shay, dancer and Middle-Eastern dance expert explains, “[i]ndividuals in various regions of the Middle East sometimes put themselves at considerable risk of severe punishment and fines, and even death, to dance.” [27] He believes the “radically differing perceptions” in some Middle-Eastern societies locate dance, sometimes violently, at the intersection of “politics, ethnicity and gender, and thus can constitute a space for political resistance” [28] This resistance has been taking place in private and public places, wherever bodies can disobey. The policing of this defiance has taken the authorities to the streets, as well as inside homes. Shay elaborates on how authorities like the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Taliban in Afghanistan not only attack dance as a “public performance activity” but also extend their assaults into the realm of dance as a “private social activity that happens behind closed doors,” thus, breaking into people’s houses to disrupt parties and arrest those involved. [29] He continues, explaining that, “[. . . ] people pay heavy bribes to guards in order to dance at weddings and parties”. [30] Faranak Amidi, an Iranian journalist, reflects on her memories of such gatherings:

[in] the absence of clubs and bars, parties in Iran have been the one place where people can dance and freely socialize—though such parties are technically breaking the law. [ . . . ] many of these parties were raided and most of my friends and I have been jailed at least once for attending an underground party. [31]

Women from all different social groups have been subject to much more severe scrutiny and abuse than men, and among many other performances and gestures, including singing, dance has been made a taboo, in order to increase the government’s control over women’s body movements and their social presence; to force them to enact demure and “moral” behavior and to maintain the purity and morality of Islamic society. From cinema to stage, from book illustrations to advertising billboards, the official representation of the female dancing body has been removed and hidden away in Iran. But the advent of smartphones and social media brought about a chance to intervene in this imposed aesthetic. Over the past decade, the internet was soon flooded with images and videos of dancing women at private parties, or of women taking advantage of unsupervised moments in public space and dancing where they were not expected to, for instance on the roof of a car. Prohibitions and limitations have effectively turned dance into a site of resistance, where artists and ordinary people can regain agency over their bodies. Intentionally or unintentionally, they dance in defiance of the hegemonic power of a repressive regime.

We Have Always Danced, For as Long as I Can Remember

In our house, my maman was the one who danced. In the afternoon she would put some of her favorite pop music on and sway to it. My sister and I, having returned from school soon after, would join in. The singers of these tunes had either ceased singing or had fled the country after the Revolution. For decades after the Revolution it was not possible to produce music one could dance to inside Iran, so it was recorded by the Iranian diaspora in North America or Europe. Iranian sociologist Asef Bayat elucidates the “anti-fun” policies of the Islamic Republic. He explains how the dogmatic interpretation of Islam by the regime led to the criminalization of music and dance, among many other activities, that were fun. [32] When watching children’s cartoons on state TV, we learned how to fill in the missing pictures of ballrooms and dances in our minds. We borrowed images from our own lives–like the one of my maman who greeted me, dancing, when I came home from school– in addition to images we saw on satellite TV, on VHS tapes, and the descriptions written in books that had escaped censorship.

For as long as I can remember, I have always known where we can dance and where we should not. The “no-dance” places of my childhood were either supervised by the authorities and moral police, or dogmatic and intolerant individuals with no forbearance who would tell us off or make trouble for us. Part of my family were more liberal and relaxed, hence dancing was an inseparable part of our gatherings. For weddings and big parties, bribing the local police to stay out of trouble was inevitable. Nevertheless, many of us recall the fear and tension owing to potential raids during parties; relying on trustworthy neighbors to keep quiet; and keeping an eye and ear out for anything suspicious. Another part of my family was a mix of political hardliners and devout Muslims. Some of them would dance in gender-segregated parties, some would even consider that to be haram (forbidden by Muslim sharia law). But outside the private zone of our houses, there was one rule: repress your body and stop moving!

In the official state public sphere, there was no trace of dance, nor its representation; in cinema, on state television, in education, nowhere. But in the trusted networks of private and public space, dance was everywhere. We always took advantage of any unsupervised moment in any place, to express ourselves through whirls and twirls. In resting areas on a road trip, in the classroom at break times, in quiet neighborhoods, in darkness and shadows, even in busy places with strangers who could apparently be trusted, judging by their looks, to be on our side. Wrists would sway, arms would swing, and shoulders would shake. In a fraction of a second bodies would shake the rules, and in no time jump back again into the social restrictions. Ultimately, the attempts of the regime to remove these moves from bodies, failed. If anything, they pushed people who might in the past have seen dance as unreligious, to defend the right to dance. Over the three decades of my observation, even those who had once opposed dance, even in segregated parties, grew tolerant of their children and grandchildren dancing. My mum recalls her parents forbidding dance when she was growing up. However, I remember during my lifetime my grandfather dancing on any occasion, and my grandmother dancing in her last years, in front of our excited faces. This transition was no doubt typical of many families in Iran. If anything, the panic and distress spread by the state led to a surge in the number of private venues hired for mixed-gender parties, and an increase in the bribery of local officials. And little by little, dancing has been transformed, ironically by the Islamic regime itself, into a form of resistance against the backward rules that seek to control bodies, especially female bodies. Dancing is still prohibited by the regime but, as an act of agency and affirmation, it has become more central to Iranian life and culture than ever before.

The Art that has no Place

I got to know Hany through Instagram. She is a self-taught free-style performer. The videos of her dancing in public spaces–in urban context, as well as remote rural places–caught my attention. In our correspondence, she told me that the non-built environment gives her a sense of freedom and spirituality, whereas around people she has to beware of who is watching, and possible threats. I interviewed her about her experience of dancing in public spaces:

If your moves are not perceived as sexy, you’re in much less trouble . . . Most of the time passers-by have positive reactions, though on a few occasions I was reproached. I normally tell people who criticize me to think about their mentality, as there is nothing wrong with dancing in the city. We are liberated in our minds and we know our bodies are what we still need to liberate. We are getting more daring and we want our bodies freed too. [33]

Hany posts videos of her performances on her public Instagram account. But even there, she avoids publishing everything. She sent me many videos of her dancing with many kinds of street music in corners of Iran which she said she would never publish. She frets that her career as a video artist will come to an end, should these videos be exposed. What she has shown me off the record, portrays a rebellious spirit swinging like a breeze with the urban tunes. Although unpublished, the documents reveal cracks in the concrete of hegemonic order, turning it on its head with a burst of joy. She carries on dancing in public spaces and her videos pile up on hard drives.

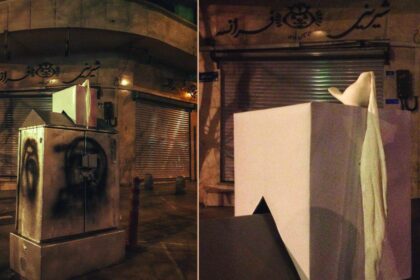

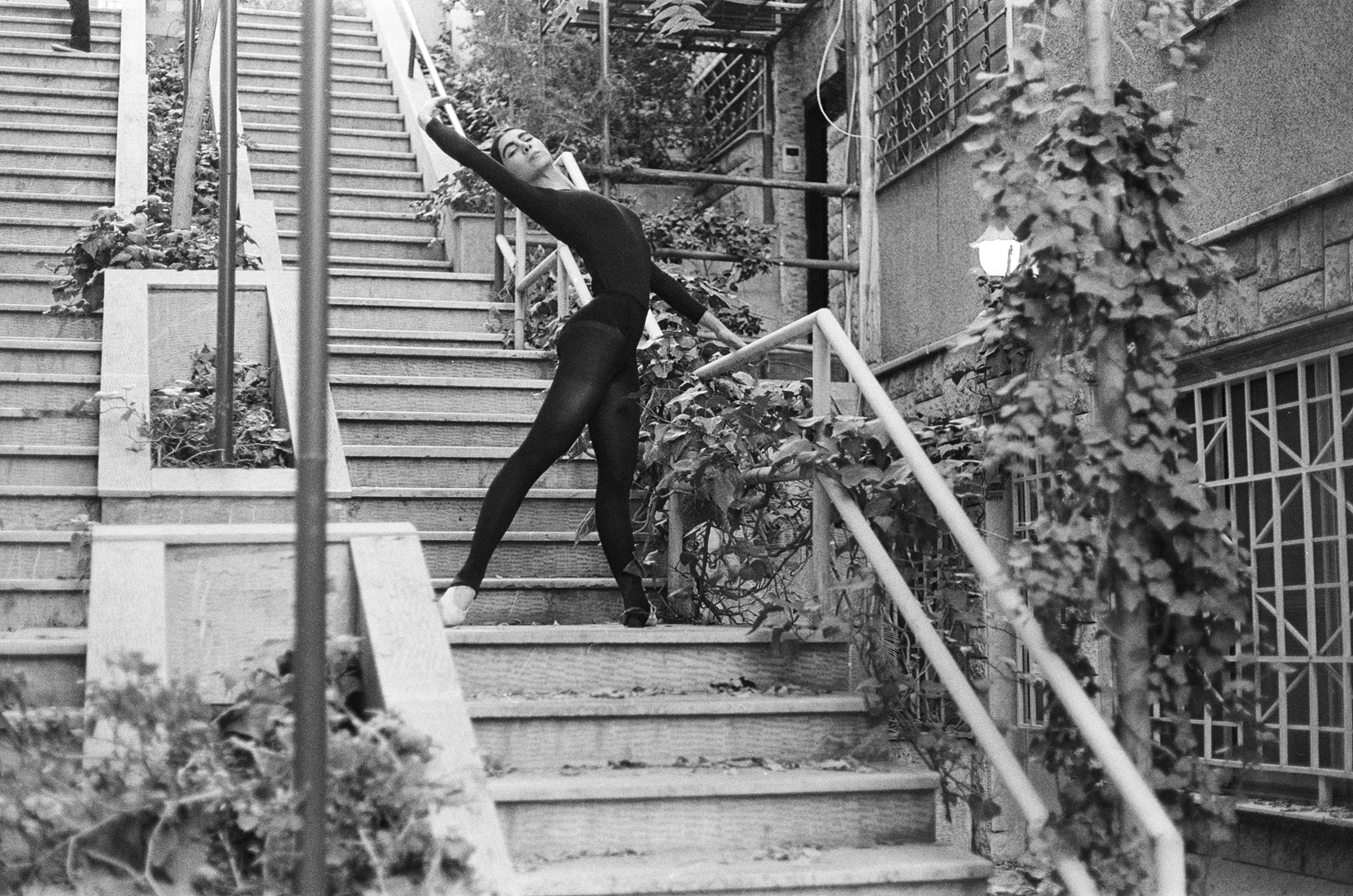

Almost two years ago I received a few images from an artist based in Tehran of a female ballet dancer posing in Ekbatan, the neighborhood in which I grew up and lived all my life in Iran. I was astonished and filled with joy, as if being told a wonderful secret about places I loved dearly. I became curious and started a conversation with Mitra, the photographer of these images. As we continued exchanging thoughts on her work, she continued and made two series of photographs. In the first phase, the dancer poses in ballet positions, in urban spaces. The dancer wears a ballet costume, which is extraordinarily brave given that covering the hair with a hijab and the body with long loose clothes, is compulsory for women and “bad hijab” can be punished with detention and flogging. As a site for her performance she chose Ekbatan and Yousef-Abad in Tehran, mainly for their relatively open cultural atmosphere. She felt safe there as they are known for being more liberal and tolerant towards social norms. For reasons she explained to me in confidence, she had to make different decisions for the next phase of her performance, covering her body and choosing gestures that were less suggestive of explicit dance moves. She reflects on the filming:

People were not making a fuss about what we were doing, but that didn’t really lessen our anxiety and fear of transgressing the norms. We didn’t have any bad experiences with the passers-by, but of course it’s different from one neighborhood to another. Dance is like fresh air in the city. What has been forbidden all of a sudden sprouts right in the middle of the city space! I wanted the female body, which is always doomed to specific limited postures, to take up the space in new ways, and I captured it with my camera in unprecedented ways too. But I can’t ever exhibit my photos inside Iran. I don’t even dare to publish them on social media. They are too taboo-breaking. [34]

Mitra explains how these experiences have changed the city for her, as she feels more familiar with places with which she did not previously have a meaningful relationship. However, her projects have no chance of being presented in the current political atmosphere. Inspired by Valie Export—the avant-garde Austrian artist who famously explored the relationship of her body with urban spaces through photography—she has now moved away from figurative dance motifs to explore the still, unmoving body, in relation to space. Her photographs prefigure another possible world, in which bodies disobey social restraints and move freely in order to interact with space in unexpected ways. For anyone familiar with those places, her photographs depict a fantasy rather than document a reality, the dream of freedom, the imagining of a possibility. The photographs create an alternative world which, on the one hand, is surreal owing to its detachment from the current situation in Iran; but on the other hand, pointing to the possibility of an alternative future, the photographs highlight the impermanence and frailty of the current regime.

My case studies thus far have included a non-professional performer and a professional photographer. Tanin Torabi is a professional dance artist based in Iran and Ireland. Her dance videos have been successful outside Iran and displayed in many festivals, bringing her international recognition. Yet, the work she has produced in Iran is unknown to Iranian audiences, since she cannot publish it openly. While she attends festivals and wins awards, inside Iran she has no connection to the formal art scene. In her film Derive (2017), which lasts for seven minutes, we see her in Tajrish Bazar, a large traditional bazar in north Tehran at a busy hour. As she positions her body in dance motifs, she moves away from the camera. The place is crowded with people, all crammed into a very narrow lane, and among so many bodies, she has to navigate carefully. Some of the passers-by look puzzled as to why she is behaving ‘oddly’ and walking in a peculiar way, some do not notice her strangeness at all. There is nothing there to suggest that this is a dance performance. Perplexed looks captured on the video reveal that she is indeed a body out-of-place. In an interview I conducted with her she reflected on her work:

I took the movement motifs from the everyday. In Derive, I took shoving as my main motif, like when you’re walking in bazar and someone shoves you and you have to quickly move to stop yourself from stumbling. [35]

Having created the choreographed motifs, Tanin then improvised the dance. She explains her work is dance-film, so the dance we watch is choreographed to be performed for the camera, and should not be seen simply as documentation. The dancing body’s movements are very ephemeral, so the camera must capture them before they disappear. “I chose that location because it was very narrow and no one would have enough time or space to see what was happening properly. And since my motifs were all bits of everyday moves, no one could question me for doing something out-of-place”. [36] As she dances, she moves forward, and the camera follows her. Thus, those who witness one movement cannot see the next, nor the previous ones. In this way the in-situ audience is constantly replaced by new members, so no one can have a coherent reading of the entire event. Tanin here takes advantage of the specific place and time in order to perform a subversive act in such a way that its very subversion is ambiguous and therefore unaccusable.

In Plain Sight (2021) is another film made by Tanin in a public space in Tehran. Here, her two main motifs are inspired by sitting, tying up shoe laces and fixing the mandatory hijab on one’s head. We see three women (including Tanin) entering the frame, one by one. They seem unconscious of each other’s presence as they stand in the distance. However, they move in harmony. “We had rehearsed the moves and parts of it were totally set up, but we didn’t want it to look very choreographed so some moves were also improvised.” [37] To prepare for, and design this piece, Tanin and her group spent a month rehearsing in a studio as well as in the actual location. For a brief moment, they enjoyed rehearsing, carefree, on benches and among trees, being creative and inspired, prancing around, before this was all spoilt by officials. She recalls how security guards constantly showed up out of blue and questioned them. They had mainly chosen the location because it reminded them of good times in the past, but the anxiety of being under constant surveillance eventually changed the feeling of the place. Their bodily reaction was to feel less comfortable and more apologetic for taking up space. Their moves shrank. They began to question what distinguishes dance from everyday movement in the female body, and how or when “normal” quotidian movements turn into transgressive acts of dance. Their conclusion was insightful: “Of course the cultural codes also depend on where and how you were raised. But we realized growing up in Iran, we somehow know, bodily, where the red lines are!” [38] Tanin not only plays with everyday movements as her motifs, but in addition, the costumes she chooses are ordinary urban outfits. In doing so, she prevents the dancing body from being easily spotted. By not standing out, the female dancer has more space to blend in when needed. In addition, she makes a statement by not distinguishing herself from ordinary people. She remains one of many, and as in her performance Derive, transgression stays transient, camouflaged and hopefully safe from censorship.

Kamnoush , like Tanin, is a professional dance artist and researcher. Based in Paris, she is a practice-researcher working on her Ph.D. in dance anthropology. Her video, I Want to Dance in Your Street (2017), starts with a black screen, accompanied by metro noises and announcements in French. Then comes a series of photomontages of Kamnoush jumping and dancing in the air in Paris. The next frame shows the street sign rue de Tehran (Tehran Street) in Paris, followed by Kamnoush dancing in the actual streets of Tehran, perhaps probing her relationship with home as an Iranian living abroad. She is wearing an oversized shirt, trousers and a loose hijab, all white. As she dances, the background changes every few seconds. The viewer sees the continuity of body movements in differing places. In reality, the dancer is recorded in various places, and the film is edited in such a way as to give a sense that the body is teleporting to different places in no time. No one else appears in the frame, but we hear passers-by murmuring. Kamnoush moves in calm and composed ways, sharply contrasting with the feeling of unease provoked by the possible trouble she might get into for dancing like this in Tehran. Unlike Tanin’s performers, the dancer in this film appears to be free, at ease and comfortable in the space. Somehow, her calm demeanor appears contradictory and shocking in an otherwise oppressive and violent city that sits at the background, like a collage of things unrelated to one another. A female body, concentrating peacefully on her movements, within a metropolis that rumbles and thunders in the background. Does she embody the repressed dream of this never peaceful and always censored city? Does her presence mark a moment of peace and harmony, in an everlasting construction site and an ever-policed state? She refuses the violence that this place has ceaselessly imposed on female bodies, as if her dance heals the sexual harassment, the police’s violence to dictate to her what to wear and how to behave, and the condescension projected onto her by the patriarchal order. Her ethereal presence appears both to represent and to affirm, the collective body of all women. I interviewed Kamnoush, who was a dance student in Iran between 2003 and 2009.

The opportunities of presenting and performing were so very little and far out of reach for women. So I never considered myself a professional dancer. Rather, I saw myself as always a learner who would perform if ever there was a chance. Even when we rehearsed for a performance, it would usually get cancelled last minute. We gradually learnt not to get frustrated by it and just to continue dancing. There was no vision, and no institution to formalize our art and activity. [39]

This inspired Kamnoush and two of her fellow dance students to establish an NGO called Dastgam, to give dance as an art some credibility through research and archiving the history of dance and dancers in Iran. Dastgam began its activities in 2006 and it lasted for over a decade. Kamnoush explains:

Dancers are inspired by spatial social bubbles that are created, in which the setting between members is more intimate, and based on trust. They take advantage of these networks for performing and presenting their works. So it’s not about public or private places, it’s rather about finding the right bubble and network in which people share values and resist the hegemonic order. We danced in these private bubbles and tried hard to prevent exposure to formal institutions and regulations. If we were to perform in relatively open places, such as women-only ceremonies, we had to be cautious about filming, as that would again expose us to the broader public, and could potentially endanger us. I always heard stories of other dancers who were detained or persecuted for some video or another that exposed their private performances. We also had to wear very loose and oversized dresses to conceal our gender as much as possible. [40]

She explains that her choice of video-dance was a conscious one, as it gave her relatively more freedom to perform in public spaces, without necessarily needing an in-situ audience. They could therefore film at times and in places that were deserted and forbidden, but then make the performance accessible via the internet. In addition, working with video gave Kamnoush the opportunity to create a longer piece from very short videos filmed in different places before the security forces or morality police arrived.

Disobedient Bodies, Alternative Possibilities

My search for women’s dance practice in public spaces in Iran has led me to buried treasure, an incredible resource of unpublished, un-exhibited visual documents, including dance-films and videos using various tactics to evade the heavy surveillance and censorship of women’s bodies in Iran. In my analysis of these works, I have tried to show how they apply the tactics of everyday life in order to perform subversion. In many ways, by shunning formal art spaces, they have embraced the realness of the streets and performed genuine acts of subversion which impact life outside official gallery spaces. By not making any explicit statements, they seek refuge in the ambiguous space between art and the quotidian. These works intervene into the dominant state-led hegemonic aesthetic that for decades has removed the female dancing body from any official representation. They occupy streets that are otherwise barred to women dancers. Like the woman dancing on her car roof with which I began this article, by using tactics such as the ephemerality of performance, all of the performers I discuss here blur the line between socially-engaged art and transgressive everyday acts, placing emphasis on the latter. In this way, they make genuine interventions into their own everyday lives, and those of their viewers, performing acts that resist oppression in concrete, meaningful ways. Asef Bayat explains how through everyday acts of resistance, rather than massive political assemblies, people in the Middle East are changing their circumstances. He calls these acts nonemovements, “the collective actions of noncollective actors.” [41] Bayat elaborates by explaining how the “street,” for those who “structurally lack institutional power of disruption,” becomes the “ultimate arena to communicate discontent.” [42] I suggest that a large segment of the artistic practice that challenges spatial gender discriminations can be found on the streets, blurring the border between feminist art and everyday acts of defiance.

The contest is over the meaning of space, and what is and what is not allowed in particular places. As the geographer Doreen Massey writes, “[t]he identities of place are always unfixed, contested and multiple. [ . . . ] Places viewed this way are open and porous,” thus, the transgressive performances that challenge the identity of place, could be read as attempts to de-stabilize “the meaning of particular envelopes of space-time”. [43] These performance interventions disrupt the hegemonic meaning of place, reinterpreting them through lived experiences. If we look into the formal art institutions in Iran today, these artistic practices go largely unnoticed by the general public, and have little bearing on the actual politics of space and bodies in Iran. I have argued that, in order to understand socially-engaged creative and artistic practice in Iran that intervenes into the patriarchal order, we need to turn to practices taking place in everyday life, and the transgressive acts through which artists reclaim the spaces of everyday life. This is where the art of presence as Bayat terms it, meets the artistic practices of those who have shunned galleries and stages. These art works have no chance of being shown in the formal art scene inside Iran. Therefore, they either remain in the artist’s archive, on social media, or with higher risk, they travel outside to be showcased in international art scenes away from the watchful eyes of authorities. In the videos I have described, bodies out-of-place, actually meet in the street. Here, both professional artists and non-artists apply the same tactics to reclaim their right to the city.

For over four decades, the Islamic Republic has dictated an aesthetics that excludes female bodies from certain places, and delimits their performances to particular gestures and acts of “modesty”. The state ceaselessly encourages women to be “perfect wives and mothers”, while diminishing social roles they take. Furthermore, it controls the image to merely represent them as docile bodies. Women in official representations do not laugh loud, they often do not run or jump around or climb trees, the state media does not even show women’s sport matches. In the official pictures, women always leave bed or bathroom with complete hijab, which has turned into a joke, but behind this bitter joke, is a brutal removal of the everyday activities that one needs to freely express and experience. Ultimately, the attempt is to internalize fear, shame and anxiety for taking up space and having strong social presence. The state representation of women has removed dancing, singing, and many other everyday performances as well as art forms. Rancière defines aesthetics as “the distribution of the sensible,” an order of things that is normalized by hegemonic power, “the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it.” [44] He writes that artistic practices are “ways of doing and making” that intervene in the general distribution of ways of doing and making as well as in the relationships they maintain to modes of being and forms of visibility. [45] The disobedient body in the cases I have analyzed here, interrupts the hegemonic aesthetics of public space in Iran, and opens it up to new meanings and interpretations. It challenges what is dictated or perceived as normal, and exposes the discrimination and oppression that are embedded in the aesthetic protocols of the state. The insubordinate dancer disrupts the hegemonic order and the documents of these performances, scattered on the internet, or hidden away on personal hard drives, configure an alternative aesthetic, that defies tyranny and embraces the possibility of a kind of emancipation.

While I have been working on this article, the Taliban has recaptured Iran’s neighboring country Afghanistan, after twenty years of U.S. and NATO occupation, leaving everyone in shock (August 2021). There are reports that singing, music and dancing have been banned for women, as well as education for girls. In June of this year Iran experienced the lowest level of voter participation in a general election in the history of the Islamic Republic. This election has resulted in the most reactionary faction of the authorities, regarding social freedom and women’s rights, to gain power since the regime began over forty years ago. Theatre has recently been removed from the disciplines taught at Sooreh (girls’ art high schools). Whether this has been a decision made by the new government or not, is unclear. But there are serious fears among women’s rights activists over the changing atmosphere in the country. As I am writing these words, a video has just appeared on social media. The young girl is probably a high school student, but it is hard to say from a distance, especially since she is wearing a mask to protect herself against COVID-19, from which Iran has suffered more than many countries in the world. She dances outside one of the Sooreh schools, in protest against the removal of a theatre course. The song to which she has carefully choreographed her movements is sung by Ghawgha Taban, a young Afghan singer who now resides in Iran and is an outspoken voice in support of women’s rights in Afghanistan. As the dance-protester moves, Ghawgha sings:

The wind blows with tension,

Dance with hope of liberation,

Dance within the ghosts’ city,

Dance in dorms and at university,

Dance, dance and dance even more

Dance, dance and dance even more

This video moved me to tears because what I am writing about, what these dancers perform, is not simply academic or aesthetic. It encapsulates the suffering, the joy, the hope, the protest, the cry for freedom, that is being expressed in spaces that are pushing these women out and closing in on them. They do not fret. They sing, they play, they perform another life, and dance another reality.

Saba Zavarei is a writer, researcher, and artist, stretched between London and Tehran. Working across the media of text, video, and performance, she explores the ways in which bodies and performative interventions contribute to the social production of space and the urban condition. Her doctoral thesis (Performance Studies and Human Geography) looks into the creation of alternative spaces of everyday life, through performances that transgress gender norms in Iran. She has published widely in Farsi and English, and is currently working on two new books, and her first documentary film.

Notes

[1] In Space Invaders (2004), Sociologist Nirmal Puwar explains how over time certain bodies are associated with certain spaces as the somatic norm of those territories, and eventually others are excluded from those spaces. Nirmal Puwar, Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place, (Oxford: Berg, 2004).

[2] Sepideh Zarrin Ghalam and Elaheh Hatami, “Gendered bodies in motion: representation of Iranian women dancers in public spaces of Tehran” in Contemporary Theatre Review, Issue 27:4 https://www.contemporarytheatrereview.org/2017/gendered-bodies-in-motion/#return-note-2291-4 (December 2017). (accessed September 5, 2021).

[https://www.contemporarytheatrereview.org/2017/gendered-bodies-in-motion/#return-note-2291-4]

[3] Susanne Foellmer, “Choreography as a Medium of Protest,” Dance Research Journal [doi:10.1017/S0149767716000395], (2016) p.68.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Heather Harrington, Site-specific protest dance: Women in the Middle East, Dancer Citizen, Issue 2 http://dancercitizen.org/issue-2/heather-harrington/ (2016). (accessed October 20, 2021)

[6] Ibid.

[7] Joanne Tompkins, Theatre’s Heterotopias, Performance and the Cultural Politics of Space (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p. 6.

[8] Paula Serafini, Performance Action (New York: Routledge, New York), p. 16

[9] Focusing on distinctions between various types of dances and the differences in how they are treated, and to what extent they are tolerated by the state, can divert us from the fundamental hostility to all dancing bodies, regardless of the style or genre. Such an approach can be found in a recent paper by Ghoncheh Tazmini (2021) on the detention of Maedeh Hojabri, a teenager who was arrested for publishing her dance videos on Instagram. Although Tazmini tries to look at the issue from a refreshing point of view, but she somehow diminishes the problem to a question of “the regime versus the ‘historical West’” (p.1296). She goes on to define “the dancing body as a site of resistance, not only for the ‘marginalized’ but, in this case, for the Iranian regime” (p. 1297). Oddly enough the oppressor becomes the marginalized. To justify her argument, she quotes from different officials who have contradictory reactions to the arrest and the forced confession by the teenager that was broadcasted on national TV, concluding that the regime and society are not “as polarized as they appear to be” (p. 1297). But in doing so, there is a danger of turning a blind eye on how the Islamic Republic, regardless of a variety of opinions (from the hardliners to the so-called reformists) in practice has exercised one and only one policy: banishing dance, and showing zero tolerance for any form of female dancing. While Tazmini tries to interpret the campaign against Hojabri’s arrest on social media as a case of the Western media stereotyping a regime repressing its own people, most independent feminist activists inside and outside of Iran have always been on the front line of protesting against these kind of violations which she calls “indigenous, post-revolutionary norms and values” (p. 1299), including this case. To them, women’s right to their body and freedom to dance is at stake, whether as a political tool or not. By stating that “dancing is not a crime” in post-revolutionary Iran, and that the harsh reaction against Hojabri is based on the Western style of her actions, she is completely ignoring the four decades of evidence of how dancers have been treated in Iran and the countless occasions on which they have been detained or persecuted, regardless of their dance style and genre of activity. The truth is that although the law remains silent on this matter, in practice there is a great deal of latitude within the existing legal code to persecute dance as a crime under the category of what officials call “unsettling the national security”.

Ghoncheh Tazmini, “‘Westoxication’ and Resistance: the Politics of Dance in Iran #dancingisnotacrime,” Third World Quarterly, 42:6, (2021) pp.1295-1313.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1886582 (accessed September 5, 2021)

[10] Anthony Shay, “Dance and human rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia” in Dance, Human Rights and Social Justice; Dignity in Motion, edited by Naomi Jackson and Toni Shaprio-Phim (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2008).

[11] Ida Meftahi, Gender and Dance in Modern Iran, Biopolitics on Stage (New York: Routledge, 2016) p. 8.

[12] Sasan Fatemi, “Music, Festivity, and Gender in Iran from the Qajar to the Early Pahlavi Period,” Iranian Studies, vol. 38, no. 3, (September 2005), p.400.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, p. 416.

[15] Meftahi, p. 31.

[16] Parya Saberi, “What it’s like to be a dancer in the Islamic Republic of Iran”, Dance Magazine, (July 2, 2019) https://www.dancemagazine.com/dance-in-iran-2638945653.html (accessed September 5, 2021).

[17] Meftahi, p. 10

[18] Ibid.

[19] Anthony Shay, “Dance and Human Rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia”, Dance, Human Rights and Social Justice, p. 78.

[20] Sepideh Zarrin Ghalam and Elaheh Hatami, “Gendered Bodies in Motion”.

[21] ‘Iran arrests six for Zumba dancing‘, BBC, (August 7, 2017)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-40880420 (accessed: September 5, 2021)

[22] “Dance in Tehran Municipality ceremony; Prosecutor-General of Iran ordered the ‘taboo-breakers’ to be prosecuted,” BBC Persian (March 7, 2018).

https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-43314475 (accessed: September 5, 2021)

[23] Anthony Shay, “Dance and Human rights in the Middle East,” p.73.

[24] Rachel Spence, “When dance gets dangerous: the perils of free expression in Iran,” Financial Times (August 20, 2020).

https://www.ft.com/content/bb399741-970a-40dd-bca6-fd60f756e70b (accessed: September 5, 2021)

[25]Anthony Shay, “Dance and Human rights in the Middle East,” p. 67.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid, p. 68.

[30] Ibid, p. 76.

[31] Faranak Amidi, “I risked everything to dance in Iran,” BBC (July 11, 2018).

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-44777677 (accessed September 5, 2021)

[32] Asef Bayat, Life as Politics (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013).

[33] Unpublished interview by the author with Hany (August 2021).

[34] Unpublished interview of the author with Mitra (August 2021).

[35] Unpublished interview by the author with Tanin Torabi (August 2021).

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Unpublished interview by the author with Kamnoush (August 2021)

[40] Ibid.

[41] Asef Bayat, Life as Politics, p.15.

[42] Ibid, p. 12.

[43] Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007), p.5 (Massey’s italics)

[44] Jacques Ranciére, The Politics of Aesthetics (London: Bloomsbury, 2011), p.7

[45] Ibid, p. 8.