Editorial | Winter 2015

Grant Kester

There is no surer way of evading the world than art, and no surer way of attaching oneself to it.

– Goethe, Elective Affinities (1809)[1]

Welcome to the second issue of FIELD. Lenin was said, perhaps apocryphally, to have danced a jig when the Bolsheviks managed to retain power in Russia longer than the 72-day life span of the Paris Commune. While the stakes for FIELD’s survival are considerably less momentous, I can say that we are delighted to be releasing our second issue this fall. While this isn’t, properly speaking, a thematic issue it has nonetheless occurred that most of our contributors touch on the same general issue; how do we determine the critical efficacy of a given art practice? Here it should be noted that “criticality” has, for some time, functioned as the implicit criterion for the evaluation of artistic or aesthetic merit in contemporary art more generally. This is, of course, consistent with the earliest concept of the aesthetic as a form of critical self-reflection (on the harmony of the faculties or the free play of our formal and sensuous drives in the virtual realm of aesthetic semblance). It should also be noted that the essentially monological concept of the self that is assumed to engage in this reflective project continues to inform contemporary accounts of art’s critical potential.

That all modernist art (not just the socially engaged variety) makes some claim to a critical efficacy is self evident, as is the fact that this capacity rests on a set of explicitly ethical claims about art’s relationship to dominant systems of power. It is equally axiomatic that the preponderance of what we know as modernist art is driven by variations of the same underlying impulse: to challenge the growing influence of (implicitly capitalistic) forms of materialism and possessive individualism. It takes no great hermeneutic effort to detect this orientation in the special privilege assigned by Kant to disinterest, in Schiller’s assault on the “reign of material needs” or in Adorno’s attack on “constitutive subjectivity” in Aesthetic Theory. At the same time, the source of art’s power to challenge this regime was to be found in its monological autonomy from the same corrupt social and political system that it hoped to transform. For Schiller the aesthetic re-invents the growing schism between works of art and the world of daily life—which would become a defining feature of modernity—as the precondition for art’s capacity to effect a harmonious reconciliation of contending classes. One symptom of modernist fragmentation (the hierarchical segregation of fine art) thus became the antidote for another (class division).

In this model concrete social or political change is merely the mechanical or pragmatic extension of the real, creative work of social transformation, which only occurs through the cognitive reprogramming of individual subjects. Any direct social or collective action is premature, and even hazardous, until we have first learned how to respect, rather than instrumentalize, the other through a singular experience of aesthetic education (whether this occurs through exposure to elevating models of high art or the spectacle of economic abjection engineered to “force” the bourgeois viewer to admit his own complicity in class oppression). This deferral of praxis is re-articulated by Adorno as a prohibition on the premature reconciliation of subject and object, or self and other, in artistic experience, which would allow the bourgeois viewer an unearned experience of aesthetic transcendence. The necessary presumption in both cases, of course, is a hierarchical separation between artists, who possess an innate capacity for critical reflection, and individual viewers (always implicitly “bourgeois”) whose consciousness remains mired in what Viktor Shklovsky famously termed “habitualization”. It is only after the (inevitably deferred) revolution, when the aesthetic reconciliation of self and other is finally universalized and made real, that we can be allowed to indulge in all those emotions (friendship, love, sympathy) that “we revolutionists,” as Trotsky once wrote, “feel apprehensive of naming”.[2] Until that time any artistic practice that traffics in the kinds of affirmative or solidarity-enhancing modes of affect necessary to actually work collectively does nothing more than provide an alibi for a fundamentally corrupt system.

As I’ve suggested, the ethical orientation of the avant-garde has historically been staged through this binary opposition between complicity and criticality, between those practices that can be seen to engage in an authentic form of (autonomous) critique, and those that can be shown to reinforce rather than challenge oppressive social or political systems. It would seem clear that these two operational modes can’t be entirely disentangled, and that this tension, between salve and salvation, between agent of radical change and alibi for the status quo, is built into the very operation of the avant-garde as a discursive apparatus. As Paul Mann describes it, the avant-garde is “not a victim of recuperation but its agent, its proper technology.”[3] Like Icarus, just how closely do artists hew to the corrosive warmth of the social before their wings are melted and they plummet to earth? These issues are even more pronounced when we turn to the arena of socially engaged art, whose very self-definition assumes the problematic counterpoint of a socially disengaged art practice. Thus, one of the central discursive tropes evident in recent criticism of socially engaged art circulates around the efficacy of “merely” local or situational actions. While there are certainly valid reasons for being skeptical of practices grounded in local sites of resistance, this critique assumes that artists today actually have the option of developing their work in conjunction with a revolutionary movement operating at a global scale. More crucially, it ignores the fact that the future evolution of new, potentially global, forms of resistance must begin precisely with the creative and practical experience of local or situational action.

This fall I wrote a short piece for the A Blade of Grass website that explores this question in more detail, using Thomas Hirschhorn’s widely celebrated Gramsci Monument (located in the Forest Houses complex in the South Bronx) as an example. I want to return to this discussion briefly here, as it bears directly on many of the questions raised in this issue of FIELD. In particular, the Gramsci Monument offers a useful illustration of the complex ideological machinations necessary for an artist whose livelihood is dependent on the collecting habits of the 1% to retain the aura of autonomous criticality necessary to be simultaneously embraced by the validating mechanisms of academic art criticism. In addition, given the increasing appropriation of “social art” by museums, art fairs, and foundations, it also provides a revealing example of the specific modes of practice that are most congenial to the institutional and ideological demands of the mainstream art world. Typically these involve temporary and ephemeral gestures that entail no long-term commitment, responsibility or investment but, rather, provide highly mediagenic moments of immersion in “other” social and cultural contexts. Certainly they don’t encourage anything as déclassé as a form of resistance or criticality that might raise troubling questions about the hegemonic function of the sponsoring institutions themselves.

For Hirschhorn, of course, the criticality of the Gramsci Monument is linked to its carefully regulated autonomy, evident in his insistence that this project is “no social work experiment, but pure art”. The most obvious subtext for this insistence is what we might term the exculpatory critique, which I’ve alluded to above. It is familiar to us from several decades of critical theory, but I’ll rehearse its general outlines here. Given the repeated failures of the working class to rise up in revolutionary protest and overthrow the entire capitalist system, the artist or theorist has come to function as a kind of protective vessel (Adorno used the term “deputy”) for a pure revolutionary spirit that must be held in trust until the proper historical moment allows for its return to the masses for final actualization. Until that time any concrete action (to improve the conditions of the oppressed, for example) only serves to compromise the exemplary freedom of artistic or intellectual production and exonerate the “system” itself from critique, by showing that some positive change is possible without a total revolution. Here the premature reconciliation of art and life replaces the premature reconciliation of self and other as the condition against which advanced art differentiates itself. The artist, in order to preserve his or her own (internalized) revolutionary purity, must abstain from concrete action and instead traffic only in various form of symbolic enactment (performances, the production of physical objects, etc.) designed to interpellate individual viewers.

One might be surprised to find a project that is so clearly indebted to the often-reviled traditions of community art presented as an exemplar of aesthetic purity. However, Hirschhorn’s evocation of purity in this context deserves closer scrutiny, as it can reveal a great deal about the increasing institutional popularity of various forms of collaborative or participatory art. The result of this mainstreaming has been a tactical shift in the constitution of autonomy itself. We have moved from a model of spatial autonomy, in which art preserves its independent criticality by remaining sequestered in museums and galleries, to a model of temporal autonomy, in which the artist preserves his or her critical independence by retaining mastery over the unfolding of a given project through time. Here the artist alone determines the moment of both origination and cessation, and the complex choreographic markers that structure the processual rhythms (of creativity, of incipient resistance, of reinvention or reorientation) set in motion by their work.

In the absence of the institutional and spatial boundaries of the museum or gallery, time, and the structuring of time, becomes the primary form through which the artist exercises his or her autonomy. It is the realm of expectation and disappointment, realization and deferral, and completion and incompletion. The orientation to time in the structuring and planning of Gramsci Monument is symptomatic. It was exhaustively event-driven, rather than process driven, combining elements of both a museum education program and a biennial (complete with its own “pavilions”). This is museum time, institutional time, teleological time, predicated on planned events and scheduled, highly programmatic, activities, and largely resistant to the improvisational emergence of new critical insight or the unforeseen social energies and antagonisms that can be generated by a messy, complex, creatively staged collaborative interaction (a process that is, more often than not, temporally disobedient). Not surprisingly, the Gramsci Monument appeared to have no real orientation to local nodes of practical resistance that might have allowed the residents of Forest Houses to integrate the ideas espoused by Antonio Gramsci, the intellectual figurehead of the project, with their own lived experience.

This sovereign relationship to temporality is clearly evident in Hirschhorn’s insistence on the “time-limited” nature of the Gramsci Monument, which came in response to a critic’s inquiry about its possible long-term effect on the Forest Houses community. Hirschhorn’s response is symptomatic:

First of all, I am happy to learn that residents want the Monument back, because this means that the project was not a failure. But I had been, since the very beginning, clear to everybody that the Gramsci Monument is a new kind of Monument, and it’s a new form of art—concerning its dedication, its location, its output and its duration . . . It’s not a Monument which understands eternity as a question of time; it’s a Monument which understands eternity as ‘here’ and as ‘now’.[4]

For Hirschhorn the purity of Gramsci Monument, and his own critical autonomy as an artist, rests on his singular ability to prescribe its temporal limits, and to refuse any responsibility for the actual effect the work might have on the Forest Houses community “after” the project is completed. Here the fundamentally monological orientation of his practice is evident. In order to instantiate and preserve his own autonomy Hirschhorn must refuse any reciprocal answerability to the site and to the unfolding social processes that might be catalyzed by his presence there. The effect of this temporal sovereignty on the community itself is apparent in the following observations; one made during the project’s eleven-week run (by the then-director of the Dia Art Foundation, which commissioned the work) and the other about one year after its conclusion by Susie Farmer (the mother of one of Hirschhorn’s chief contacts at Forest Hills).

The seminars on Saturdays are packed. There are people coming every day: that’s a sign that the residents are interested in the project. I remember I was there one morning just before it opened to the public and a group of kids was running toward the monument, screaming, “The monument is about to open. Let’s go to the computer room!” There is ownership. The Gramsci Monument is part of Forest Houses; it’s part of their lives.

– “The Momentary Monument: Philippe Vergne on Thomas Hirschhorn’s Ode to Gramsci,” Walker Art Museum Magazine (September 12, 2013)[5]

Whitney Kimball: I remember the last time I talked to you, you were telling me about kids who were getting really inspired by the art there. Have you seen that [enthusiasm] grow at all over the year? [Note: Last year, Susie had told me a story about a little boy who’d been particularly inspired by the Monument, and had been thinking about going into an art program because of it.]

Susie Farmer: No. And one little boy who we particularly thought would be very good [with art], I don’t even know if he’s going to school now like we’d encouraged him to do. The children are asking every day if it’s going to come back. No, they’re not going to come back. It was a one-time thing. Every day they had something to look forward to. They would get up early and come to the Monument. It was something they never had in their area before, and they may never have it again.

– Whitney Kimball, “How Do People Feel about the Gramsci Monument One Year Later?,” Artfcity (August 20, 2014)[6]

By refusing to use his considerable prestige (and the Dia’s equally considerable financial resources) to create a more sustainable transformation in Forest Houses, Hirschhorn imagines that he is offering an indirect critique of the failure of existing public agencies to fulfill their own obligation to support the Forest Houses residents themselves, invoking what he somewhat cryptically terms the “non-necessity of the world as it is”. This is a straightforward, and fairly predictable, reiteration of the exculpatory critique outlined above. For Hirschhorn, art’s function is to provide a brief, symbolic anticipation of a different world, evoking the possibility of concrete change or political empowerment (in the case of the Gramsci Monument, via the staged consumption of Marxist philosophy or critical theory) but never seeking to realize it. The residents of Forest Houses can be employed, trained, photographed and lectured to, but never engaged in a process that entails their own agency in the development of new forms of resistance or criticality.[7] If the after-effect of this approach is some level of disillusionment that the unprecedented outpouring of resources and media attention devoted to the Forest Houses community had been abruptly withdrawn, it’s preferable to a scenario in which the state could point to some more lasting improvement in the community to excuse it’s own inaction.

By leaving the community with no sustainable model of creative resistance Hirschhorn can preserve his own image as an uncompromising critic of capitalism while siphoning off the social capital generated by working-class residents, whose cultural and economic difference is a narcotic to arts institutions and funders anxious to demonstrate their social commitment (so long as it remains short term), without calling into question their institutional privilege or their hegemonic function within the global art market (now valued at $54 billion dollars per-year). Of course one can’t expect Hirschhorn, or any artist, to resolve the economic crisis of the working class in the South Bronx. But one can ask what it means for an artist to offer the hope of something different from “the world as it is,” while using the frustration and disappointment produced by its failed realization to demonstrate his unwillingness to indulge in the “premature” reconciliation of art and practical action. Here the people of Forest Hills, their kindled enthusiasm, their aroused hopes, their participatory involvement, become the medium for a “critical” gesture intended primarily for art world consumption.

In This Issue…

This analysis leads us to our current issue. It features an illuminating exchange between Noah Fischer and Sebastian Loewe, produced in response to Loewe’s critique of the appropriation of the Occupy Movement by Documenta and the Berlin Biennale in FIELD issue #1. Taken together, Fischer and Loewe’s essays provide a useful précis of two key positions on the question of art’s critical efficacy; one of which sees the art world as simply another site from which to stage resistance against an increasingly integrated global economy, and the other which warns us of the (bourgeois) art world’s perennial ability to assimilate an “astonishing amount of revolutionary themes without ever seriously putting into question its own continued existence or that of the class which owns it,” as Walter Benjamin famously observed in “The Author as Producer”. Is the art world a site of cooption or contestation? Of course it is both. The critical challenge we face is in deciphering the hieroglyphic mechanisms of each of these processes as they are set in motion at specific sites, and accounting for their strategic and tactical relationship to the larger forces of neo-liberal capitalism.

Gloria Durán and Alan Moore offer another perspective on the complex play of complicity and critique in their analysis of La Tabacalera, a vacant state-owned tobacco factory that was turned over to a group of activist artists in Madrid by the Spanish Ministry of Culture in 2010. Durán and Moore trace the complex interrelationship between the Spanish state, under the guise of a “new institutionality” policy, and a network of Madrid-based art and social justice groups, as they sought to create an autonomous, self-organized social center rooted in leftist traditions of activist squatting. The Tabacalera, as they describe it, was “a social center with permission”. Many of the questions raised by the Tabacalera involved the tension between alternative social spaces as sites at which a new, prefigurative form of political life can be nourished and the pragmatic demands entailed by operating a large facility under some level of state supervision. What kind of decision-making processes would be effective and representative, while retaining the critical political agency of the squat? And how did the groups involved in the Tabacalera manage internal schisms, associated with the role of the Asociación Panteras Negras (Black Panthers), which sought to function as a “social center within a social center”? Durán and Moore provide an invaluable glimpse into the tensions and insights produced by the negotiations necessary to make the Tabacalera both operational and inclusive.

C. Greig Crysler, in the first of a two-part study of the emergence of new forms of participation in contemporary architecture and design, addresses a similar question. More specifically, Crysler is concerned to challenge the assumption that participation per se is a necessarily progressive political form, and to unpack the complex historical process by which participation was mobilized in architecture and planning discourse during the 1960s, only to succumb to the forces of bureaucratic rationality. In this critique he turns to the work of urban theorist Horst Rittel for his key concept of “wicked” problems. Rittel is referring to our tendency to “solve” systematic problems with stopgap or temporary solutions that simply defer the unresolved tensions not fully addressed in the original formulation of the problem itself. Here we find a corollary instantiation of the critique of local or situational action I’ve sketched above. Working in the context of Great Society-era social programs, Rittel developed an innovative analysis of the ways in which the formulation of design problems often obscures the contingency of the social structure that precedes and determines them. His analysis here bears a potentially revealing relationship to the process by which museums, biennials and foundations sponsor, commission, and regulate, participatory or “social art” commissions. The second part of Crysler’s essay will appear in FIELD this spring.

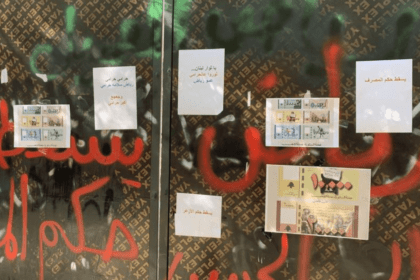

We’re also pleased to publish Mariana Botey’s interventionist address to the 2015 SITAC conference (SITAC XII), which was organized by Carin Kuoni of the Vera List Center for Art and Politics under the theme of “Arte, Justamente/Just Art”. SITAC, the Simposio Internacional de Teoría Sobre Arte Contemporáneo, is a famed conference that regularly brings leading artists, theorists and critics to Mexico City for wide ranging discussions on events of importance to contemporary art. In her remarks here Botey unpacks the conference theme, which became especially acute with the current crisis of governmentality in Mexico and the nation-wide protests associated with the kidnapping and murder of 43 students in the state of Guerrero. Can we assume that any artistic practice possesses a necessary relationship to justice in a period of such profound and systematic crisis? And if not, then what capacities, what operations, can art deploy in order to claim this relationship? Here Botey identifies art with a “state of exception” to a regime predicated on political violence. “Art does not need to be defined as just or unjust,” as Botey writes, its “space is juridically a space of transgression—and in its strongest cases a form of radical relationship with the truth.” We want to give special thanks to Sara Solaimani for translating Botey’s talk and also providing an introduction.

This issue also features two reviews by FIELD Editorial Collective members. These include Noni Brynjolson’s review of John Robert’s new book Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde in which he attempts to revive an authentically critical form of avant-garde artistic practice based on a re-articulation of the Hegelian concept of negation. Adorno’s work plays a central role in Robert’s effort to re-function the historical avant-garde for the contemporary moment. Here art retains its critical power by refusing any premature “escape” into political praxis, serving only to critique existing structures of power and meaning from an autonomous distance. It thus reclaims its role (outlined above) as the single cultural site at which an ethos of pure negation holds out against the onslaught of repressive desublimation that characterizes modern capitalism. Our second review comes from Paloma Checa-Gismero, who attended the twelfth Bienal de La Habana this summer. In her review Checa-Gismero discusses the particular focus of this year’s Bienal on community-based practices, examining commissioned projects by Graciela Duarte, Manuel Santana and César Cornejo, among others. Duarte and Santana’s contribution was a reiteration of their long term Echando Lápiz project, which employed a process of literal “botanizing on the asphalt” to engage community members in a more reflective relationship to the urban environment though the close analysis and documentation of local plant species. Cornejo’s Puno MoCA project set in motion a series of new institutional and collaborative relationships with city residents by using their homes as satellite exhibition spaces for the Bienal itself. Here the boundaries between public and private and art and life are creatively transgressed.

As I noted in our first editorial, we are especially concerned to expand the scope of discussion around socially engaged art beyond the already discourse-laden U.S. and European circuit, and beyond the Anglophone world more generally. One of the signal features of the expansion of socially engaged art is its remarkable global scope. It represents a far too complex and situationally nuanced field for any single critic or writer. For this reason we have plans to appoint a series of Corresponding Editors; critics and writers with expertise in specific regions. With this issue of FIELD we are delighted to introduce our first Corresponding Editor for China, Bo Zheng. Zheng is a critic, artist and historian specializing in socially engaged art. He received his Ph.D. from the Visual and Cultural Studies Program at the University of Rochester in 2012 and is currently revising his dissertation, The Pursuit of Publicness: A Study of Four Chinese Contemporary Art Projects, for publication as a book. His essays on Chinese socially engaged art have been published in multiple journals and books (most recently in Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century, MIT Press, 2015) and he is an editorial board member of the Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art. Zheng received an Early Career Award from Hong Kong’s Research Grants Council in 2014 and a Professional Development Award from City University of Hong Kong in 2015. Currently he is building an online database and a MOOC, both on Chinese socially engaged art. Zheng currently teaches at the School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong, and is an affiliated member of the Institute of Contemporary Art and Social Thought at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China. As an artist Zheng has worked with a wide range of communities, including the Queer Cultural Center in Beijing and Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong. His project Family History Textbook received a Prize of Excellence from the Hong Kong Museum of Art in 2005 and Karibu Islands received a Juror’s Prize from the Singapore Art Museum in 2008. His recent art projects include Sing for Her, a participatory installation created with minority singing groups in Hong Kong, and Plants Living in Shanghai, a found botanical garden and an open online course created with ecologists and humanities scholars in Shanghai. We look forward to presenting Zheng’s research in upcoming issues (he’s currently planning an interview with the Taiwanese artist Wu Mali). For more information on his work see: cityu-hk.academia.edu/BoZheng and www.tigerchicken.com.

Grant Kester is the founding editor of FIELD and Professor of Art History in the Visual Arts department at the University of California, San Diego. His publications include Art, Activism and Oppositionality: Essays from Afterimage (Duke University Press, 1998), Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (University of California Press, 2004) and The One and the Many: Agency and Identity in Contemporary Collaborative Art (Duke University Press. 2011). He has recently completed work on Collective Situations: Dialogues in Contemporary Latin American Art 1995-2010, an anthology of writings by art collectives working in Latin America produced in collaboration with Bill Kelley Jr., which is under contract with Duke University Press.

Notes

[1] Goethe, Elective Affinities (1809), translated by David Constantine, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.152.

[2] Leon Trotsky, “Communist Policy Toward Art,” (1923), https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1923/art/tia23.htm

[3] Paul Mann, The Theory-Death of the Avant Garde (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991), p.92.

[4] Whitney Kimball, “How Do People Feel about the Gramsci Monument One Year Later?,” Artfcity (August 20, 2014).

[5] Philippe Vergne, Former Director, Dia Art Foundation and current Director, MOCA Los Angeles. “The Momentary Monument: Philippe Vergne on Thomas Hirschhorn’s Ode to Gramsci,” Walker Art Museum Magazine (September 12, 2013) http://www.walkerart.org/magazine/2013/philippe-vergne-interview-hirschhorn-gramsci.

[6] Kimball, op cit. http://artfcity.com/2014/08/20/how-do-peoplefeel-about-the-gramsci-monument-one-year-later/. Erik Farmer, the Forest Hills Tenant Association President, and Susie Farmer’s son, registered a similar concern: “Well I thought [the reactions] would be a little more mixed, but mostly, everyone misses it. They wish it was back. Everyone keeps asking me Is it going to come back this year, is it going to come back . . . I had to tell them, nope, that was it, not again this year. So there’s nothing for the kids to do now, they’re really bored. You can see how nobody’s out here, when the monument was here last year, it was full of people outside.”

[7] The governing matrix for all of these processes remains the a priori plan devised by Hirschhorn before the event begins. Hirschhorn discusses the centrality of the plan in an interview with Benjamin Buchloh: “. . . my idea was that I wanted to make sculpture out of a plan, out of the second dimension. I said to myself, ‘I want to make sculpture, but I don’t want to create any volumes.’ I only want to work in the third dimension—to conceive sculpture out of the plan, the idea, the sketch. That is what I want to make a sculpture with: the thinking and conceiving, the various plans the planning.” Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, “An Interview with Thomas Hirschhorn,” October 113 (Summer 2005), p.81.